The Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as an Innovation Factor That Enables the Creation of New Sustainable Business

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Development

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

2.2. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

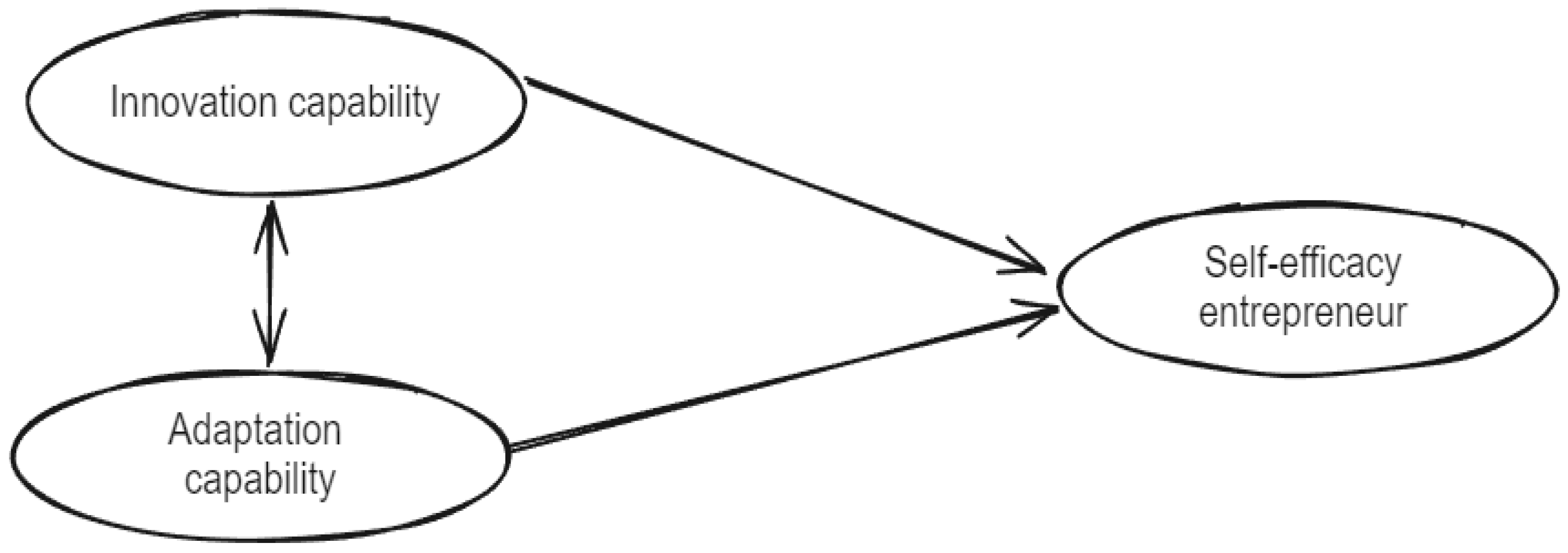

2.3. Hypothetical Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Instrument and Analysis

3.2. Sample

3.3. Questionnaire Design

- Ensure the questionnaire had an appropriate length.

- Verify that the questions were clearly understood, especially given the young target audience.

- Confirm that the questions addressed the defined topics and were in the correct order.

- Improve the reliability and validity of the questionnaire (by eliminating problematic questions).

- To minimize potential common method bias [46], the following measures were taken:

- A brief introduction at the beginning of the survey ensured the confidentiality of the collected data.

- Information about the required completion time was provided to set clear expectations.

- The survey was structured into sections with questions presented in a random order.

- Control questions and reverse-worded items were used.

3.4. Measurement Scales

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Model Measures

4.2. Structural Model

- (a)

- CFI (Comparative Fit Index): The CFI measures incremental fit by comparing the proposed model to a baseline null model. Values range from 0 to 1, with a value close to 1 indicating a better fit. A CIF value above 0.95 is generally considered an acceptable model fit.

- (b)

- RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation): The RMSEA assesses the overall fit of the proposed model to the population. It indicates how well the model’s covariances fit and provides a measure of the model’s fit to the population. RMSEA values range from 0 to 1, with values below 0.06 considered an excellent fit.

- (c)

- SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual): The SRMR evaluates the difference between observed and model estimated correlations. With values ranging from 0 to 1, an SRMR value below 0.08 typically indicates a good model fit.

4.3. Model Results

4.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Lines

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romero-Martínez, A.M.; Milone, M. El emprendimiento en España: Intención emprendedora, motivaciones y obstáculos. J. Glob. Compet. Gov. 2016, 10, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Industria y Turismo, La DGEIPYME Publica el Informe “Cifras PYME”, Web DGIPYME, Marzo 2024. Available online: https://plataformapyme.es/es-es/Paginas/noticias-detalles-simple.aspx?idnoticia=854 (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Comisión Europea. Decisión de Ejecución de la Comisión, Por la Que se Aprueba el Programa de Cooperación «Interreg VI-A España-Portugal (POCTEP)» Para Optar a la Ayuda del Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional Conforme al Objetivo de Cooperación Territorial Europea (Interreg) en España y Portugal CCI 2021TC16RFCB005; Comisión Europea: Bruselas, Belgium, 2022.

- CEOE (Confederación Española de Organizaciones Empresariales). Portugal: Economía, Relaciones Bilaterales y Oportunidades de Negocio Para las Empresas Españolas, Web CEOE, Internacional, Mayo 2023. Available online: https://www.ceoe.es/es/ceoe-news/internacional/portugal-economia-relaciones-bilaterales-y-oportunidades-de-negocio-para (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Torres-Mancera, R.; Martínez-Rodrigo, E.; Amaral Santos, C. Sostenibilidad femenina y startups: Análisis de la comunicación del liderazgo de mujeres emprendedoras en España y Portugal. Rev. La. Com. Soc. 2023, 81, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEPYME (Confederación Española de Pequeña y Mediana Empresa). Indicador CEPYME Sobre la Situación de la PYME. Coyuntura de las Pequeñas y Medianas Empresas Españolas. II Trimestre de 2023. CEPYME. Madrid. Available online: https://cepyme.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/%E2%80%A2Informe-Indicador-CEPYME-2do-T-2023_CEPYME_V4.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Usman, F.O.; Eyo-Udo, N.L.; Etukudoh, E.A.; Odonkor, B.; Ibeh, C.V.; Adegbola, A. A critical review of ai-driven strategies for entrepreneurial success. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2024, 6, 200–215. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, D.H.; Kaciak, E.; Fadairo, M.; Doshi, V.; Lanchimba, C. How to erase gender differences in entrepreneurial success? Look at the ecosystem. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Rasool, S.F.; Xuetong, W.; Asghar, M.Z.; Alalshiekh, A.S.A. Investigating the nexus between critical success factors, supportive leadership, and entrepreneurial success: Evidence from the renewable energy projects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 49255–49269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Espés, C.; Víctor Ponce, P.; Romero Fúnez, D.; Cervera Oliver, M. ¿Qué factores afectan a la supervivencia y éxito empresarial de las pymes en épocas de crisis? RCyT CEF 2022, 470, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huicab-García, Y. Gestión del talento humano en el entorno BANI. 593 Digit. 2023, 8, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Transformación Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Emprendimiento Verde de las Mujeres y el Emprendimiento de las Mujeres en el Ámbito Rural. MITECO, Madrid. Marzo 2023. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/ministerio/planes-estrategias/igualdad-de-genero/2023-03-10presentacion_principalesresultados_infome_miteco_2023_emprendimiento_mujeres_verde_rural_tcm30-560304.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Giudici, G.; Guerini, M.; Rossi-Lamastra, C. The creation of cleantech startups at the local level: The role of knowledge availability and environmental awareness. Small. Bus. Econ. 2019, 52, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Champion, J.A.; Barrutia Barreto, I.; Bejar, L.H.; Huamani, O.; Borja, J.; Flores Asqui, P.R. La educación y la intención emprendedora en estudiantes universitarios: Una revisión en Latinoamérica. Rev. Conhecimento Online 2024, 1, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraj, D.; Ul Islam, M.I.; Qureshi, I.H.; Basheer, S.; Baba, M.M.; Nissa, V.U.; Asif Shah, M. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention for sustainable tourism among the students of higher education institutions. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebsen, S.; Senderovitz, M.; Winkler, I. Shades of green: A latent profile analysis of sustainable entrepreneurial attitudes among business students. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088148 (accessed on 1 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 8–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strat. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strat. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3094429 (accessed on 1 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) Enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20141992 (accessed on 2 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The Evolution of the Dynamic Capabilities Framework. In Artificially and Sustainability in Entrepreneurship, FGF Studies in Small Business and Entrepreneurship; Adams, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Lew, Y.K. Post-entry survival of developing economy international new ventures: A dynamic capability perspective. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, H.; Achtenhagen, L.; Andersson, S. The changing role of network ties and critical capabilities in the international new ventures already developed. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. Entrepreneruship and Dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Lumpkin, G.T. The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Greene, P.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J. Bus. Venturing 1998, 13, 295–316. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883-9026(97)00029-3 (accessed on 2 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gist, M.E. Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 472–485. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/258514 (accessed on 2 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Balkin, D.B.; Baron, R.A. Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, M.S.; Syed, F.; Naseer, S.; Chinchilla, N. Role of adaptive leadership in learning organizations to boost organizational innovations with change self-efficacy. Curr. Psychol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A.S. Green Innovation, Self-Efficacy, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Economic Performance: Interactions among Saudi Small Enterprises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Gomez, C.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C. Artificial intelligence as an enabling tool for the development of dynamic capabilities in the banking industry. Int. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 16, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Coelho, A.; Moutinho, L. Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 2020, 92–93, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, F.; Chaudhry, S.A. Autoeficacia empresarial ecológica y sus resultados: El papel mediador de la actitud hacia el emprendimiento. Boletín Asiático Gestión Ecológica Econ. Circ. 2024, 4, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Rosing, K.; Zhang, S.X.; Leatherbee, M. Un modelo dinámico de incertidumbre empresarial e identificación de oportunidades de negocio: La exploración como mediador y la autoeficacia empresarial como moderador. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 835–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Impact of institutional support and green knowledge transfer on university students’ absorptive capacity and green entrepreneurial behavior: The moderating role of environmental responsibility. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.K. Can sustainable entrepreneurship be achieved through green knowledge sharing, green dynamic capabilities, and green service innovation? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liboni, L.B.; Cezarino, L.O.; Alves, M.F.R.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Venkatesh, V.G. Translating the environmental orientation of firms into sustainable outcomes: The role of sustainable dynamic capability. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2023, 17, 1125–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, I.W.; Wardana, I.M.; Setiawan, P.Y.; Widagda, I.G.N.J.A. Entrepreneurship education and green entrepreneurial intention: A conceptual framework. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2022, 6, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-H. Green Transformational Leadership and Green Performance: The Mediation Effects of Green Mindfulness and Green Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6604–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amui, L.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Kannan, D. Sustainability as a dynamic organizational capability: A systematic review and a future agenda toward a sustainable transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 5th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, B.R. Common method variance techniques. In Cleveland State University, Department of Operations & Supply Chain Management. Paper AA11; SAS Institute Inc.: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pongtanalert, K.; Assarut, N. Entrepreneur Mindset, Social Capital and Adaptive Capacity for Tourism SME Resilience and Transformation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, J.L.; Kasim, A.; Ardyan, E. Understanding the Consumers of Entrepreneurial Education: Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation among Youths. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psichometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Lacker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3151312 (accessed on 2 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Winter, S.G. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzao, G.; Rizzi, F. On the conceptualization and measurement of dynamic capabilities for sustainability: Building theory through a systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 135–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D.; Pontrandolfo, P. Green product innovation in manufacturing firms: A sustainability-oriented dynamic capability perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Avram, D.; Ovcharova, N.; Engelmann, A. Dynamic capabilities for sustainability: Toward a typology based on dimensions of sustainability-oriented innovation and stakeholder integration. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 2969–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Z.; Tian, H.H.; Cheablam, O. Promoting sustainable development: Multiple mediation effects of green value co-creation and green dynamic capability between green market pressure and firm performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Yu, R.; Hu, F.; Zhou, H.; Hu, H. How can China’s medical manufacturing listed firms improve their technological innovation efficiency? An analysis based on a three-stage DEA model and corporate governance configurations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 123456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaraan, F.; Elmarzouky, M.; Hussainey, K.; Venkatesh, V.G.; Shi, Y.; Gulko, N. Reinforcing green business strategies with Industry 4.0 and governance towards sustainability: Natural-resource-based view and dynamic capability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 3588–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh, N.Q.; Hien, L.M.; Do, Q.H. The Relationship between Transformation Leadership, Job Satisfaction and Employee Motivation in the Tourism Industry. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, I. Dynamic capabilities: A review of past research and an agenda for the future. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratković Njegovan, B.; Vukadinović, M.; Šiđanin, I.; Bunčić, S.; Njegovan, M. Optimistic Belief in One’s Own Capableness as a Factor of Entrepreneurial Sustainability: The Assessments of Self-Efficacy from the Perspective of Serbian Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourato, I.; Dias, Á.; Pereira, L. Estimating the Impact of Digital Nomads’ Sustainable Responsibility on Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ordinary Capabilities | Dynamic Capabilities | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Technical efficiency in business functions | Achieving congruence with customer needs and with technological and business opportunities |

| Mode of attainability | Buy or build (learning) | Build (learning) |

| Tripartite schema | Operate, administrate, and govern | Sense, size, and transform |

| Key routines | Best practices | Signature processes |

| Managerial emphasis | Cost control | Entrepreneurial asset orchestration and leadership |

| Priority | Doing things right | Doing the right things |

| Imitability | Relatively imitable | Inimitable |

| Result | Technical fitness (efficiency) | Evolutionary fitness (innovation) |

| Variable | Distribution | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Spain | 77.9 |

| Portugal | 22.1 | |

| Gender | Male | 35.5 |

| Female | 64.2 | |

| Other | 0.3 | |

| Age intervals (years) | 18–24 | 8.3 |

| 25–34 | 19.7 | |

| 35–44 | 28.8 | |

| 45–54 | 29.8 | |

| 55 and above | 13.4 | |

| Level of education | Doctorate | 2.8 |

| Master | 12.7 | |

| Bachelor or equivalent | 27.8 | |

| Graduate | 9.6 | |

| Vocational Education and Training | 21.6 | |

| Upper secondary | 12.4 | |

| Secondary | 12.7 | |

| Primary/None | 0.3 |

| Construct | Items * | References |

|---|---|---|

| Innovation capability (transforming business processes for success) | [Q25] Would you be willing to face unexpected changes, such as legislative changes, or reconfigure your business to a more sustainable one? | [32] |

| [Q26] Would you be willing to reconfigure your business to make it more sustainable? | [33] | |

| [Q27] Would you be interested in hiring new professional profiles that contribute to making your activities more transparent (providing information through the web, social media, etc.)? | ||

| [Q28] Would you be interested in working only with suppliers who assure you that their business is green (responsible and sustainable)? | [39] | |

| [Q29] Would you be willing to join networks or associations that make your business more sustainable? | ||

| [Q30] Would you be willing to innovate in the processes you employ and/or the products you offer? | ||

| Adaptation capability (change, learn, and reconfigure) | [Q8] To what extent do you consider entrepreneurship necessary to remain active in the labor market in the medium term? | [40] |

| [Q9] To what extent do you consider green entrepreneurship as an opportunity to enter the labor market in the short term? | [48] | |

| [Q10] To what extent do you find green (sustainable) entrepreneurship exciting? | [42] | |

| [Q11] To what extent do you see green entrepreneurship engaging with the social and business fabric of your region/province or county of residence? | ||

| Green Entrepreneurial self-Efficacy | [Q12] To what extent do you think pursuing something related to sustainability is beneficial to you because you have family or friends who have already done it? | [36] |

| [Q13] To what extent do you think that being involved in something related to sustainability is beneficial because you have a strong network to succeed? | [49] | |

| [Q14] To what extent do you think that pursuing something related to sustainability is beneficial for you because you have information on grants to support it? | [33] | |

| [Q15] To what extent do you think that engaging in sustainability-related activities is beneficial for you because it offers an opportunity to improve your income? | ||

| [Q16] To what extent do you think that pursuing something related to sustainability is good for you because you are unemployed or currently in a job you don’t like? | ||

| [Q19] To what extent do you feel you have the knowledge and skills to develop “a new activity” that will improve the sustainability of your business/workplace or community? | ||

| [Q20] To what extent do you think you would be successful if you undertook something related to sustainability? |

| Construct | Item | Regression Coefficients | ß * | AVE | Composite Reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE ** | CR *** | p-Value | |||||

| Innovation Capability | Q25 | 0.757 | 0.038 | 19.867 | <0.001 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.92 |

| Q26 | 0.988 | 0.031 | 31.828 | <0.001 | 0.85 | |||

| Q27 | 0.974 | 0.033 | 29.355 | <0.001 | 0.82 | |||

| Q28 | 1.002 | 0.032 | 30.961 | <0.001 | 0.84 | |||

| Q29 | 1.019 | 0.032 | 32.067 | <0.001 | 0.85 | |||

| Q30 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.84 | |||

| Adaptation Capability | Q8 | 0.815 | 0.031 | 26.136 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Q9 | 0.916 | 0.028 | 32.23 | <0.001 | 0.86 | |||

| Q10 | 0.869 | 0.03 | 28.805 | <0.001 | 0.82 | |||

| Q11 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.87 | |||

| Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy | Q12 | 0.021 | 0.044 | 23.447 | <0.001 | 0.76 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Q13 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.80 | |||

| Q14 | 1.062 | 0.041 | 25.735 | <0.001 | 0.85 | |||

| Q15 | 0.990 | 0.040 | 24.584 | <0.001 | 0.83 | |||

| Q16 | 1.008 | 0.044 | 22.864 | <0.001 | 0.78 | |||

| Q19 | 0.739 | 0.04 | 18.482 | <0.001 | 0.66 | |||

| Q20 | 0.733 | 0.035 | 20.667 | <0.001 | 0.72 | |||

| Innovation Capability | Adaptation Capability | Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Capability | 0.7 | - | - |

| Adaptation Capability | 0.5 | 0.7 | - |

| Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Measure | Estimate | Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| CFI | 0.963 | >0.95 |

| SRMR | 0.095 | <0.08 |

| RMSEA | 0.055 | <0.06 |

| Item | Regression Coefficients | ß *** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE * | CR ** | p-Value | ||||

| Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy | ⟵ | Innovation Capability | 0.48 | 0.04 | 10.93 | <0.001 | 0.48 |

| Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy | ⟵ | Adaptation Capability | 0.36 | 0.04 | 8.41 | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| Innovation Capability | ⟷ | Adaptation Capability | 0.73 | 0.02 | 38.94 | <0.001 | 0.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanchez-Garcia, V.E.; Gallego, C.; Marquez, J.A.; Peribáñez, E. The Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as an Innovation Factor That Enables the Creation of New Sustainable Business. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167197

Sanchez-Garcia VE, Gallego C, Marquez JA, Peribáñez E. The Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as an Innovation Factor That Enables the Creation of New Sustainable Business. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167197

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchez-Garcia, Victoria Eugenia, Cristina Gallego, Juan Antonio Marquez, and Elena Peribáñez. 2024. "The Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as an Innovation Factor That Enables the Creation of New Sustainable Business" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167197

APA StyleSanchez-Garcia, V. E., Gallego, C., Marquez, J. A., & Peribáñez, E. (2024). The Green Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as an Innovation Factor That Enables the Creation of New Sustainable Business. Sustainability, 16(16), 7197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167197