Weaving a Sustainable Future for Fashion: The Role of Social Enterprises in East London

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability

2.2. Fashion and Sustainability

2.3. Sustainable Business Models and Social Enterprises

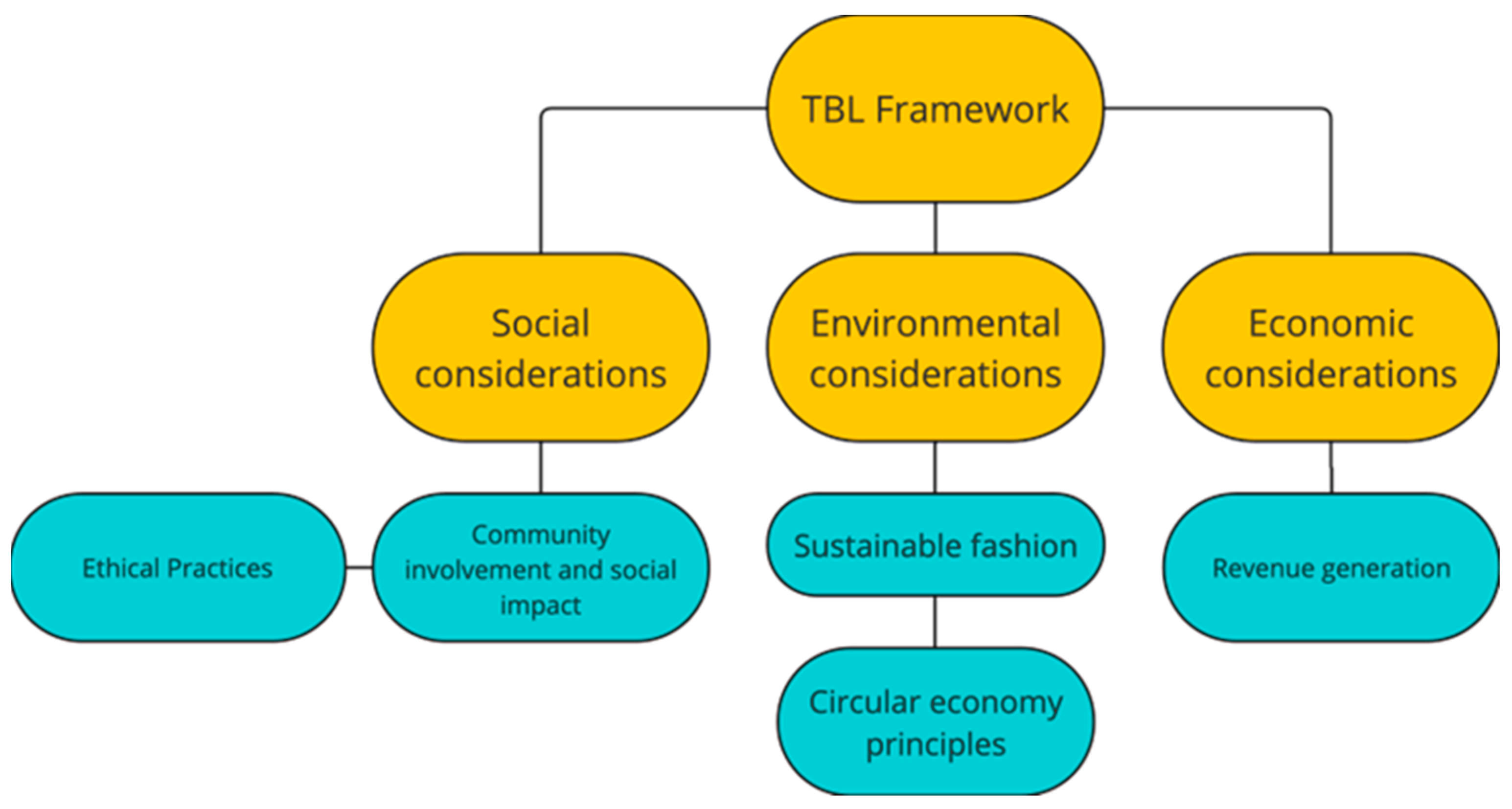

2.4. TBL Framework

2.5. Social Capital

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study Selection

3.1.1. Case Study 1: Making for Change

3.1.2. Case Study 2: Stitches in Time

3.2. Data Collection Methods

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Validity

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. RQ1: How Do the Social Enterprises in the East London Fashion Cluster Leverage the TBL Framework to Promote Sustainable Practices in the UK Fashion Industry?

4.1.1. Social Considerations

4.1.2. Environmental Considerations

4.1.3. Economic Considerations

4.2. RQ2: How Do Social Enterprises in the East London Fashion Cluster Utilise Social Capital to Facilitate the Transition towards Sustainability in the UK Fashion Industry?

4.2.1. Bonding Social Capital

4.2.2. Bridging Social Capital

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Themes | Key Findings | Excerpts from Interviews and Focus Groups |

|---|---|---|

| RQ1: How do the social enterprises in the East London fashion cluster leverage the TBL framework to promote sustainable practices in the UK fashion industry? | ||

| Social Considerations | Social enterprises leveraged a variety of ethical practices. | Focus group 1, Participant A: “There is a lot of flexibility here with start times, appointments, family care, childcare, and other personal responsibilities. If there’s a week when you can’t work due to family commitments, allowances are made, so there’s a system in place”. Reiterating this, another participant said “I have tried approaching other workplaces, but it just didn’t fit our lifestyle with childcare, appointments, and health needs. Here, you have complete flexibility. Everyone here manages their own schedule to a certain degree”. Focus group 2, Participant B: “They accommodate our cultural needs and religious beliefs, we have space to pray, can dress comfortably, including wearing the hijab. It’s a safe space where we feel accepted and celebrated for our culture”. |

| These enterprises want to change the perception of manufacturing as a factory-based environment to one that values skilled craftsmanship and ethical working conditions. | Anna Ellis, head of business development at Making for Change said “We do still have that connotation when you think of a factory, you immediate thing is to think of a sweatshop, and that’s what we’re trying to change”. Gracie Sutton, enterprise and production manager at Stitches in Time, said the following: “Brands can showcase our flexible work practices and the various sustainable methods we use. I think by sharing the stories and the impact on the makers, it gives a different example of how the fashion industry can work. Hopefully, that’s a good guideline for how people can work differently within various factories and settings” | |

| They work closely with brands, individual designers, and other clients to ensure better quality and cost-effective products. | Gracie said “When smaller brands work with us, we help support them in terms of sampling and figuring out where we can reduce costs, or how to enhance and utilise the skills of the team as well. So, in that sense, they are not just coming to us with a technical pack and dictating what is being made. We are helping and supporting one another to produce something, which I think is great”. Similarly, Anna said “We offer more hands-on support than a typical manufacturer, meaning we closely examine their products. We also advise them on costing and techniques to produce garments that are either of better quality or more cost-effective due to improved manufacturing methods”. | |

| Social enterprise’s initiatives had a significant social impact, particularly through training programs that empowered trainees with personalised support and skills development. | Paul, Chief Executive Officer at Stitches in Time said “We have a waiting list for our training courses that seems to be never-ending. But that’s great; it shows there is a desire, there is a need, and that people gain value from it”. | |

| Community-driven initiatives by the enterprises foster social inclusion and economic empowerment, contributing to the growth of East London’s fashion cluster. | This sentiment is echoed by Paul who said “I find the way it contributes to East London’s fashion cluster is quite intriguing. As our story spreads not only through our efforts but also through brands that share it, it shines a light on our internal culture and the communities involved. This supports our role as a model and communicates the value of our work to other community enterprises, creating a ripple effect. Perhaps some of this influence will even shape the future creators of the next fashion wave. It’s an interesting cycle”. | |

| Environmental Considerations | Social enterprises are committed to circular economy principles and collaborate with brands to upcycle, repair, mend and recycle products. | Talking about a collaboration between Stitches in Time and Making for Change, where they partnered with the renowned fashion brand ‘Monsoon’, Grace said “We recently collaborated with Monsoon alongside Making for Change, involving both our trainees and employees. Together, we utilised our embroidery skills to enhance Monsoon’s products, focusing particularly on upcycling dead stock items”. Making for Change also recycle waste as confirmed by Anna in the following statement: “We recycle our textile waste by partnering with a third-party start up that turns it into other products”. |

| Using innovative solutions, such as AI, to enhance on-demand manufacturing. | Highlighting this, Anna said “We want to explore ways in which AI can make production more efficient and more sustainable”. | |

| Sustainable practices incur higher costs due to the increased production time. | Focus Group 2, Participant D: “the amount of time it took us to unpick a particular garment, cut it, and create something new with it was much longer than sewing a garment from scratch”, | |

| Social enterprises enhanced participants’ awareness of environmental sustainability, fostering a sense of pride and fulfilment in contributing to a greener world. | Focus Group 2, Participant B: “The training programs and our work have enabled us to better understand the carbon footprint associated with our processes, and how we can reduce the wastage of fabric and other materials to promote sustainable practices”. Adding to this, another participant said the following: “we’re not just churning out garment after garment without knowing what happens to it afterward. There’s a story behind each piece, and there are people behind it”. | |

| Economic Considerations | Social enterprises ensure the commercial viability of their projects and commissions by meticulously calculating production costs. | Gracie highlighted that “We spend a lot of time ensuring that the cost of production is viable for the team. During sampling, we calculate how long it takes to make a product based on the quantity we’re producing. Once we reach around a hundred units or more, we switch to a production line to speed up the process. This involves detailed calculations and close collaboration with the client or brand to ensure they understand both the costs and the timeline. If they have a target cost in mind, we can adjust the design to meet their expectations and requirements”. |

| The viability of on-demand manufacturing is a crucial factor for social enterprises. As noted, sustainability often involves producing in small quantities, which can be more costly due to inefficiencies and the use of offcuts. | Anna said “We may not necessarily be the cheapest; our pricing may not always match what our clients expect, but we explain our costs and try to collaborate where possible. However, commercial viability is very important to us”. | |

| RQ2: How do social enterprises in the East London fashion cluster utilise social capital to facilitate the transition towards sustainability in the UK fashion industry? | ||

| Bonding Social Capital | The East London fashion cluster utilises bonding social capital through community involvement, with enterprises like Stitches in Time engaging beneficiaries in co-creation. | Grace mentioned that “Stitches in time was built around the needs of the beneficiaries. They are always part of the conversation about how we grow and navigate the enterprise. They have a lot of say in what we do and the commissions we take on as well”. |

| Social enterprises reinforce skills development, with trained individuals, such as women in East London, volunteering to train others, creating more job opportunities and revitalising the local manufacturing industry. | Paul highlighted that “I believe Stitches in time’s existing strengths as a social enterprise is its ability to connect particularly well with the Bangladeshi diaspora through skill-based cultural crafts. This connection is already a source of pride, fostering community communication and shaping social interactions”. | |

| Bonding social capital within the enterprise community fosters trust and collaboration, with strong bonds facilitating support, knowledge exchange, and professional growth among members. | Focus Group 1, Participant C said “My work is comfortable; it feels like a home away from home. It doesn’t feel like coming to work; it’s like being with friends, and I feel very comfortable here”. Focus Group 2, Participant D: A participant commented the following: “I am taking many of the skills that I have learned here and using them in my private time for friends, family and private clients”. | |

| Personal connections and support from social enterprises provide emotional support during challenging times, strengthening commitment to community initiatives. | Focus Group 1, Participant B: “In one of our classes, we have a woman who doesn’t have the leave to remain in the UK, she doesn’t speak English, and she has a brain tumour, so we were like heavily involved with helping her with her appointments. Being there, when she had to sign for her operation and all my colleagues went with her to the anaesthesia room because she was nervous. And that’s just like individualised led case, and we were there when she woke up from her surgery to give her support”. | |

| Bridging Social Capital | Collaborations between enterprises leverage their combined expertise, resulting in higher-quality work. These partnerships provide mutual support and create opportunities for shared learning. | Paul said “We are quite good at collaborating, and we have a long organisational history of helping shape other programs or other project work because people come to us as a kind of community engagement specialist in that sense”. |

| Connections between enterprises go beyond joint projects, including ongoing partnerships to provide skills development support for their trainees. | Paul said “I think it’s a shared desire, especially between us and Making for Change, to promote an ethical production base in East London. It’s something we’re deeply interested in as an organisation. It’s exciting to leverage our small-scale efforts to make this happen, not just as a story to tell, but by partnering with other organisations. We can share experiences, particularly in working with communities and how it can best benefit people”. This collaborative effort was also affirmed during discussions with focus group participants. | |

| The enterprise collaborates with local manufacturers to provide trainees with practical experience that leads to employment opportunities. Educational partnerships and institutional support further enhance training programs and contribute to building a sustainable network within the fashion industry. | Anna highlighted that “There are several accelerator-type programs available to support organisations like ours. I have participated in a manufacturing forum that promotes innovative practices and processes in manufacturing. The Fashion District periodically hosts forums like these, offering competitions where manufacturers pitch ideas for financial support to bring them to life”. Focus group 2, Participant E: “When we did the modest fashion program, we collaborated with students from London College of Fashion, a women’s wear designer and an embroidery student. We also had someone who did printmaking. The designer who led the class, she’s now open to mentoring if we’re interested in starting a business or something like that. And then we had Toby Meadows, a fashion business consultant who’s helped lots of fashion startups and worked with many brands around the world. So yeah, it’s like we’ve had this opportunity to meet all these people in the field, and it kind of gives you an idea of what you can do with just a seed of an idea”. | |

References

- Pal, R.; Gander, J. Modelling Environmental Value: An Examination of Sustainable Business Models within the Fashion Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.; Weerasinghe, D. Towards Circular Economy in Fashion: Review of Strategies, Barriers and Enablers. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 2, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, E. Appalling or Advantageous? Exploring the Impacts of Fast Fashion from Environmental, Social, and Economic Perspectives. J. Glob. Bus. Community 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.K. Slow Fashion in a Fast Fashion World: Promoting Sustainability and Responsibility. Laws 2019, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.M.-H.; Cheung, J.; Leslie, C.A.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Suen, D.W.-S.; Tsang, C.-W. Revolutionizing the Textile and Clothing Industry: Pioneering Sustainability and Resilience in a Post-COVID Era. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Berger-Grabner, D. Sustainability in Fashion: An Oxymoron? In Innovation Management and Corporate Social Responsibility: Social Responsibility as Competitive Advantage; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Vassalo, A.L.; Marques, C.G.; Simões, J.T.; Fernandes, M.M.; Domingos, S. Sustainability in the Fashion Industry in Relation to Consumption in a Digital Age. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st-century Business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratan, D. Success Factors of Sustainable Social Enterprises Through Circular Economy Perspective. Visegr. J. Bioeconomy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekan, M.; Jonas, A.E.G.; Deutz, P. Circularity as Alterity? Untangling Circuits of Value in the Social Enterprise–Led Local Development of the Circular Economy. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 97, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovani, C.; Whittaker, P. Social Enterprise, Creative Arts, and Community Development for Marginal or Migrant Populations. In Sustainability and the Social Fabric; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2017; pp. 115–141. [Google Scholar]

- McRobbie, A.; Strutt, D.; Bandinelli, C. Fashion as Creative Economy: Micro-Enterprises in London, Berlin and Milan; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fashion District the East London Fashion Cluster, Draft Strategy and Action Plan; London. 2017. Available online: https://www.fashion-district.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/East-London-Fashion-Cluster-Draft-and-Strategy-Plan.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Barroga, E.; Matanguihan, G.J. A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2022, 37, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbu, U.E. Visually Hypothesising in Scientific Paper Writing: Confirming and Refuting Qualitative Research Hypotheses Using Diagrams. Publications 2019, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staicu, D. Characteristics of Textile and Clothing Sector Social Entrepreneurs in the Transition to the Circular Economy. Ind. Textila 2021, 72, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, M.F.; Marina, A.; Leiva, E.I.B. Sustainable Business Models in Fashion Industry: An Argentine Social Enterprise Fostering an Inclusive and Regenerative Value Chain. In Responsible Consumption and Sustainability: Case Studies from Corporate Social Responsibility, Social Marketing, and Behavioral Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Borchardt, M.; da Silva, M.G.; de Carvalho, M.N.M.; Burdzinski, C.S.; Kirst, R.W.; Pereira, G.M.; da Silva, M.A. Uncaptured Value in the Business Model: Analysing Its Modes in Social Enterprises in the Sustainable Fashion Industry. J. Creat. Value 2024, 10, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, M.S. Sustainability and Triple Bottom Line Planning in Social Enterprises: Developing the Guidelines for Social Entrepreneurs. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Available online: https://gat04-live-1517c8a4486c41609369c68f30c8-aa81074.divio-media.org/filer_public/6f/85/6f854236-56ab-4b42-810f-606d215c0499/cd_9127_extract_from_our_common_future_brundtland_report_1987_foreword_chpt_2.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Gunder, M. Sustainability: Planning’s Saving Grace or Road to Perdition? J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 26, 208–221. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K. Ethical Foundations in Sustainable Fashion. Text. Cloth. Sustain. 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Alhaddi, H. Triple Bottom Line and Sustainability: A Literature Review. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2015, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, O.; Hu, D.; Fung, B.C.M. A Systematic Literature Review of Fashion, Sustainability, and Consumption Using a Mixed Methods Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Abbate, S.; Nadeem, S.P.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Slowing the Fast Fashion Industry: An All-Round Perspective. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 38, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The Global Environmental Injustice of Fast Fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. Sustainable Development of Slow Fashion Businesses: Customer Value Approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solino, L.J.S.; de Lima Teixeira, B.M.; de Medeiros Dantas, Í.J. The Sustainability in Fashion: A Systematic Literature Review on Slow Fashion. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2023, 8, 164–202. [Google Scholar]

- de Aguiar Hugo, A.; de Nadae, J.; da Silva Lima, R. Can Fashion Be Circular? A Literature Review on Circular Economy Barriers, Drivers, and Practices in the Fashion Industry’s Productive Chain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, G. Circular Economy: Illusion or First Step towards a Sustainable Economy: A Physico-Economic Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J. What Is Sustainable Fashion? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. An. Int. J. 2016, 20, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M.P. A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. Fashion in a Circular Economy. Sustain. Fash. A Cradle Upcycle Approach 2017, 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product Design and Business Model Strategies for a Circular Economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombi, C.; D’Itria, E. Fashion Digital Transformation: Innovating Business Models toward Circular Economy and Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Rakib, N.; Min, J. An Exploration of Transformative Learning Applied to the Triple Bottom Line of Sustainability for Fashion Consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, T.S.; Johannsdottir, L.; Pedersen, E.R.G.; Niinimäki, K. Social, Environmental, and Economic Value in Sustainable Fashion Business Models. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 141091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable Business Models: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, M.C.; Santhià, C.; Bosone, M. How Hybrid Organizations Adopt Circular Economy Models to Foster Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.-K.; Chang, Y.-T. Exploring the Key Elements of Sustainable Design from a Social Responsibility Perspective: A Case Study of Fast Fashion Consumers’ Evaluation of Green Projects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller Connell, K.Y.; Kozar, J.M. Introduction to Special Issue on Sustainability and the Triple Bottom Line within the Global Clothing and Textiles Industry. Fash. Text. 2017, 4, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Kim, Y.-K. An Empirical Test of the Triple Bottom Line of Customer-Centric Sustainability: The Case of Fast Fashion. Fash. Text. 2016, 3, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez, C.; Sierra, V.; Rodon, J. Sustainable Operations: Their Impact on the Triple Bottom Line. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, A.; Meade, L.M. The Business Case for Sustainability: An Application to Slow Fashion Supply Chains. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2018, 46, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, H.R. How Social Enterprises Called Benefit Organisations Fulfil the Triple Bottom Line. Social. Bus. 2020, 10, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfield, C.; Ellison, N.B.; Lampe, C.; Vitak, J. Online Social Network Sites and the Concept of Social Capital. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 1392–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.H.; Gardner, K.H.; Carlson, C.H. Social Capital and Walkability as Social Aspects of Sustainability. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3473–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.; Ferrazzi, G.; Schryer, F. Getting the Goods on Social Capital. Rural. Sociol. 1998, 63, 300–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siisiainen, M. Two Concepts of Social Capital: Bourdieu vs. Putnam. Int. J. Contemp. Sociol. 2003, 40, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gauntlett, D. Making Is Connecting: The Social Power of Creativity, from Craft and Knitting to Digital Everything; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. Sociol. Theory 1983, 1, 201–233. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners; Sage Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative & Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Jaspersen, L.J.; Thorpe, R.; Valizade, D. Management and Business Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.B.V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Parameters | Description | Scientific Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance | Cases must be chosen based on their relevance to answering specific research questions. | The selected cases directly address and align with the research questions, ensuring focused and pertinent data. |

| Richness | The selected cases must generate rich information for an in-depth exploration of the phenomenon under study. | Each case provides comprehensive and detailed data, allowing for deep exploration and understanding. |

| Analytic generalisability | Cases must offer insights into broader theoretical contexts, ensuring findings can be analytically generalised to similar contexts. Statistical generalisability to a larger population is not sought. | The findings from the cases are expected to provide insights that are applicable to other similar contexts, though not necessarily to a larger statistical population. |

| Potential to generate believable explanations | Cases must have high potential to generate credible explanations about the role and impact of social enterprises | The data from the cases are expected to support robust and convincing explanations regarding the impact and role of social enterprises. |

| Ethics | Obtaining informed consent from all participants, clearly explaining the study’s purpose, procedure, and potential risks. | Ethical standards are maintained by ensuring informed consent and transparency about the study’s procedures and risks. |

| Feasibility | The study must be practical within the available time, resources, and access constraints. | The focused selection of cases allowed for manageable and effective data collection and analysis, given the available resources and regional scope. |

| Core Operations | Core Focus | Outcomes for Trainees | Partnerships and Support | Community Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training programs (professional skills and qualifications in fashion manufacturing and production) | Skills development, job creation, community support | Volunteering opportunities leading to full-time employment | Collaborations with educational institutions and local councils | Bangladeshi immigrants, local communities based in east London |

| Commercial production services for the fashion industry | Socially responsible practices Environmental sustainability | Social inclusion and economic empowerment | Partnerships with fashion industry networks and support from regional development initiatives |

| Interviewee Job Title and Organisation | Date of Interview | Location of Interview | Type of Interview | Duration of Interview |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paul, Chief Executive Officer at Stitches in Time | 28 March 2024 | Stitches in Time, Tower Hamlets, East London | Face to face | 45 min |

| Gracie Sutton, Enterprise and Production Manager at Stitches in Time | 28 March 2024 | Stitches in Time, Tower Hamlets, East London | Face to face | 45 min |

| Anna Ellis, Head of Business Development at Making for Change | 30 May 2024 | Microsoft Teams | Online | 38 min |

| Focus Group 1: Stitches in Time Participants | Coded as | Date | Location of Interview | Type of Focus Group | Duration of Interview |

| Rohima Begum (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant A | 28 March 2024 | Stitches in Time, Tower Hamlets, East London | Face to face | 1 h 15 min |

| Malika (Former Trainee and Volunteer) | Participant B | ||||

| Tayeeba Begum (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant C | ||||

| Shaleha Sharmi Chawdhury Mitale (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant D | ||||

| Fateha Hussain (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant E | ||||

| Farida Yesmin (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant F | ||||

| Focus Group 2: Making for Change Participants | Coded as | Date | Location of Interview | Type of Focus Group | Duration of Interview |

| Ruma Boumik (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant A | 6 June 2024 | Microsoft Teams | Online | 58 min |

| Fieruza Khanom (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant B | ||||

| Shahana Begum (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant C | ||||

| Nosira Begum (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant D | ||||

| Dicko Coulibaly (Former Trainee and Employee) | Participant E |

| Phase | Description of the Process |

|---|---|

| Transcribing data (if necessary), reading and re-reading the data, noting down initial ideas. |

| Coding interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the entire data set, collating data relevant to each code. |

| Collating codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. |

| Checking if the themes work in relation to the coded extracts (Level 1) and the entire data set (Level 2), generating a thematic ‘map’ of the analysis. |

| Ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story the analysis tells, generating clear definitions and names for each themes. |

| The final opportunity for analysis. Selection of vivid, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, relating back of the analysis to the research question and literature, producing a scholarly report of the analysis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ashiq, R. Weaving a Sustainable Future for Fashion: The Role of Social Enterprises in East London. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167152

Ashiq R. Weaving a Sustainable Future for Fashion: The Role of Social Enterprises in East London. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167152

Chicago/Turabian StyleAshiq, Rubab. 2024. "Weaving a Sustainable Future for Fashion: The Role of Social Enterprises in East London" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167152

APA StyleAshiq, R. (2024). Weaving a Sustainable Future for Fashion: The Role of Social Enterprises in East London. Sustainability, 16(16), 7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167152