Foreign Trade as a Channel of Pandemic Transmission to the Agricultural Sector in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Export of Agri-Food Products

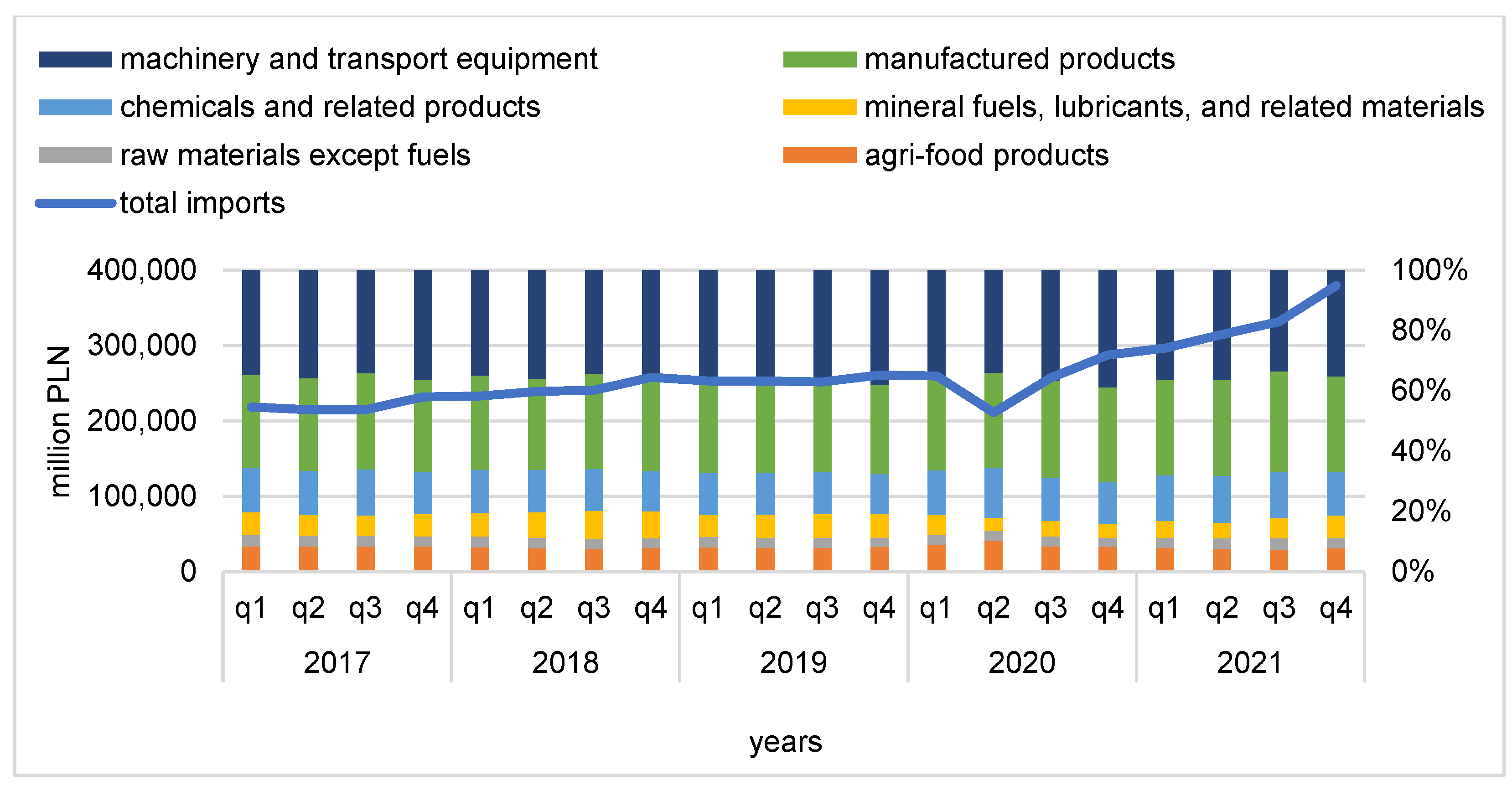

4.2. Import of Agri-Food Products

4.3. Merchandise Trade Balance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, Y.; Wang, G.; Cai, X.P.; Deng, J.W.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, H.H.; Chen, Z. An overview of COVID-19. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2020, 21, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Tan, W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, K.; Karpio, A.; Wielechowski, M.; Woźniakowski, T.; Żebrowska-Suchodolska, D. Polska Gospodarka w Początkowym Okresie Pandemii COVID-19; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.; Tomiura, E. Thinking Ahead about the Trade Impact of COVID-19. In Economics in the Time of COVID-19; Baldwin, R., di Mauro, B.W., Eds.; CERP Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Czech, K.; Wielechowski, M.; Kotyza, P.; Benešová, I.; Laputková, A. Shaking stability: COVID-19 impact on the Visegrad Group countries’ financial markets. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Kost, K.J.; Sammon, M.C.; Viratyosin, T. The unprecedented stock market impact of COVID-19. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Kutan, A.M.; Gupta, S. Black swan events and COVID-19 outbreak: Sector level evidence from the US, UK, and European stock markets. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 75, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodell, J.W. COVID-19 and finance: Agendas for future research. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 35, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoleni, S.; Turchetti, G.; Ambrosino, N. The COVID-19 outbreak: From “black swan” to global challenges and opportunities. Pulmonology 2020, 26, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petropoulos, F.; Makridakis, S. Forecasting the novel coronavirus COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wind, T.R.; Rijkeboer, M.; Andersson, G.; Riper, H. The COVID-19 pandemic: The ‘black swan’for mental health care and a turning point for e-health. Internet Interv. 2020, 20, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Yeh, C.W. Global financial crisis and COVID-19: Industrial reactions. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 42, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notteboom, T.; Pallis, T.; Rodrigue, J.P. Disruptions and resilience in global container shipping and ports: The COVID-19 pandemic versus the 2008–2009 financial crisis. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2021, 23, 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, D.; Vines, D. The economics of the COVID-19 pandemic: An assessment. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36 (Suppl. S1), S1–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, J.M.; Pardey, P.G. Agriculture in the global economy. J. Econ. Perspect. 2014, 28, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, J.; Countryman, A.M. The importance of agriculture in the economy: Impacts from COVID-19. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 103, 1595–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethier, J.J.; Effenberger, A. Agriculture and development: A brief review of the literature. Econ. Syst. 2012, 36, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bournaris, T.; Moulogianni, C.; Arampatzis, S.; Kiomourtzi, F.; Wascher, D.M.; Manos, B. A knowledge brokerage approach for assessing the impacts of the setting up young farmers policy measure in Greece. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 57, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobiecki, R. Globalizacja a Funkcje Polskiego Rolnictwa; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sobiecki, R.; Kowalczyk, S. Interwencjonizm w erze globalizacji. Kwart. Nauk. Przedsiębiorstwie 2019, 51, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizou, E.; Karelakis, C.; Galanopoulos, K.; Mattas, K. The role of agriculture as a development tool for a regional economy. Agric. Syst. 2019, 173, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruère, G.; Brooks, J. Characterising early agricultural and food policy responses to the outbreak of COVID-19. Food Policy 2021, 100, 102017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, T.; Bórawski, P.; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A.; Szeberényi, A.; Perkowska, A. Changes in Logistics Activities in Poland as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J.; Pound, J.; Qiao, B. COVID-19: Channels of Transmission to Food and Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, M.; Śpiewak, R. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on sustainable food systems: Lessons learned for public policies? The case of Poland. Agriculture 2022, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędruchniewicz, A.; Kozak, S.; Maśniak, J.; Mikuła, A. Kanały i Mechanizmy Oddziaływania Pandemii COVID-19 na Rolnictwo w Polsce; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepaniak, I.; Ambroziak, Ł.; Drożdż, J. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na przetwórstwo spożywcze i eksport rolno-spożywczy Polski. Ubezpieczenia Rol.—Mater. Stud. 2020, 73, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandrejewska, A.; Chmielarz, W.; Zborowski, M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Perception of Globalization and Consumer Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambardzumyan, G.; Gevorgyan, S. The impact of COVID-19 on the small and medium dairy farms and comparative analysis of customers’ behavior in Armenia. Future Food 2022, 5, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, S. Sektor żywnościowy w czasach pandemii. Kwart. Nauk. Przedsiębiorstwie 2020, 56, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusz, B.; Witek, L.; Kusz, D.; Chudy-Laskowska, K.; Ostyńska, P.; Walenia, A. The Effect of COVID-19 on Food Consumers’ Channel Purchasing Behaviors: An Empirical Study from Poland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, Z.F.; Sobhani, S.M.; Barbosa, M.W.; Sousa, P.R. Transition to a sustainable food supply chain during disruptions: A study on the Brazilian food companies in the Covid-19 era. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 257, 108782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, P.; Islam, S.; Duarte, P.M.; Tazerji, S.S.; Sobur, A.; Zowalaty, M.; Ashour, H.M.; Rahman, T. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food production and animal health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 121, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroziak, Ł. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na handel rolno-spożywczy Polski: Pierwsze doświadczenia. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW W Warszawie—Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2020, 20, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, M.; Li, J.; Qin, Q. Rare disasters, exchange rates, and macroeconomic policy: Evidence from COVID-19. Econ. Lett. 2021, 209, 110099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, S.; Grant, J.; Sydow, S.; Beckman, J. Has global agricultural trade been resilient under coronavirus (COVID-19)? Findings from an econometric assessment of 2020. Food Policy 2022, 107, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erol, E.; Saghaian, S.H. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Dynamics of Price Adjustment in the U.S. Beef Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, A. (Ed.) Rynek środków produkcji dla rolnictwa. In Stan i Perspektywy; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warszawa, Poland, 2019–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bański, J.; Mazur, M. Means of Production in Agriculture: Farm Machinery. In Transformation of Agricultural Sector in the Central and Eastern Europe after 1989; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jędruchniewicz, A.; Wielechowski, M. Prices of Means of Production in Agriculture and Agricultural Prices and Income in Poland During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. H—Oeconomia 2023, 57, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilinova, A.; Dmitrieva, D.; Kraslawski, A. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on fertilizer companies: The role of competitive advantages. Resour. Policy 2021, 71, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitaritonna, C.; Ragot, L. After Covid-19, will seasonal migrant agricultural workers in Europe be replaced by robots. CEPII Policy Brief 2020, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bochtis, D.; Benos, L.; Lampridi, M.; Marinoudi, V.; Pearson, S.; Sørensen, C.G. Agricultural workforce crisis in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.; Kortum, S.; Neiman, B.; Romalis, J. Trade and the Global Recession. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 3401–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, G.S.; Gao, G.P.; Silva, F.B.; Song, Z. Unconventional Monetary Policy and Disaster Risk: Evidence from the Subprime and COVID–19 Crises. J. Int. Money Financ. 2022, 122, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmelech, E.; Tzur-Ilan, N. The Determinants of Fiscal and Monetary Policies During the COVID-19 Crisis. NBER Work. Pap. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biuletyn Statystyczny; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2017–2023.

- Wieczorek, P. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na światowy handel towarowy—Lata 2020–2021. Kontrola Państwowa 2022, 67, 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Szajner, P. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na sytuację na rynkach rolnych w Polsce. Ubezpieczenia Rol.—Mater. Stud. 2020, 1, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkowiak, H.; Gutowski, T. Polska gastronomia w czasie pandemii. Tutoring Gedanensis 2021, 6, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramza-Michałowska, A.; Kulczyński, B. Kierunki zmian w gastronomii w pandemii. Przemysł Spożywczy 2021, 75, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczek, R. Rynek mięsa w Polsce w dobie koronawirusa SARS-Cov-2. Zeszyty Naukowe SGGW w Warszawie. Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2020, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mikuła, A.; Maśniak, J.; Gruziel, K. The economic and production-related situation of polish agriculture over the period from 2015–2021. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2022, XXIX, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bułkowska, M. Polski handel zagraniczny produktami rolno-spożywczymi w dobie pandemii COVID-19. Przemysł Spożywczy 2021, 75, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engemann, H.; Yaghoob, J. COVID-19 and changes in global agri-food trade. Q Open 2022, 2, qoac013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Quarter | Total | Agri-Food Products | Raw Materials Except Fuels | Mineral Fuels, Lubricants, and Related Materials | Chemicals and Related Products | Manufactured Products | Machinery and Transport Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | q1 | 1.5 | −2.3 | 2.7 | −1.5 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 2.3 |

| q2 | −0.7 | −0.9 | 6.1 | −11.5 | 0.8 | −1.8 | 0.5 | |

| q3 | 0.0 | 6.5 | −5.5 | −5.5 | −0.1 | 1.7 | −3.0 | |

| q4 | 4.3 | 1.8 | −1.4 | −17.7 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 8.7 | |

| 2020 | q1 | −0.6 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 18.1 | 7.3 | −2.0 | −3.7 |

| q2 | −14.1 | −2.8 | −8.8 | −40.1 | −7.2 | −10.9 | −21.4 | |

| q3 | 20.0 | 5.9 | 10.3 | 12.3 | 10.4 | 19.0 | 31.1 | |

| q4 | 12.8 | 5.3 | 10.7 | 15.6 | 5.7 | 10.5 | 19.4 | |

| 2021 | q1 | 0.8 | −1.7 | 13.8 | 23.4 | 4.6 | 1.7 | −1.7 |

| q2 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 12.3 | 16.1 | 8.9 | 6.3 | 3.3 | |

| q3 | −0.4 | 6.5 | −3.0 | 20.3 | 3.1 | 3.0 | −7.5 | |

| q4 | 12.9 | 8.9 | 6.5 | 41.1 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 16.5 |

| Year | Quarter | Total | Agri-Food Products | Raw Materials Except Fuels | Mineral Fuels, Lubricants, and Related Materials | Chemicals and Related Products | Manufactured Products | Machinery and Transport Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | q1 | −1.8 | −0.2 | 7.3 | −20.0 | 2.3 | −2.1 | −0.5 |

| q2 | −0.2 | −1.6 | −5.3 | 5.9 | 0.7 | −3.6 | 2.6 | |

| q3 | −0.5 | −1.0 | −1.2 | 1.6 | −0.7 | 6.1 | −5.6 | |

| q4 | 3.6 | 7.6 | −4.0 | 4.1 | −1.8 | −2.7 | 10.8 | |

| 2020 | q1 | −0.4 | 7.2 | 9.7 | −15.3 | 11.8 | 2.5 | −4.9 |

| q2 | −18.7 | −6.1 | −17.3 | −47.4 | −8.4 | −15.2 | −23.7 | |

| q3 | 21.8 | 0.6 | 17.7 | 46.8 | 4.1 | 24.5 | 32.0 | |

| q4 | 11.8 | 9.2 | 5.2 | −1.4 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 18.1 | |

| 2021 | q1 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 24.7 | 12.4 | 3.5 | −3.7 |

| q2 | 6.1 | 1.1 | 11.3 | −1.8 | 9.6 | 6.6 | 5.6 | |

| q3 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 15.7 | 35.2 | 3.1 | 9.2 | −3.1 | |

| q4 | 14.5 | 18.7 | −1.3 | 25.7 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 17.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maśniak, J.; Jędruchniewicz, A. Foreign Trade as a Channel of Pandemic Transmission to the Agricultural Sector in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167072

Maśniak J, Jędruchniewicz A. Foreign Trade as a Channel of Pandemic Transmission to the Agricultural Sector in Poland. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167072

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaśniak, Jacek, and Andrzej Jędruchniewicz. 2024. "Foreign Trade as a Channel of Pandemic Transmission to the Agricultural Sector in Poland" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167072

APA StyleMaśniak, J., & Jędruchniewicz, A. (2024). Foreign Trade as a Channel of Pandemic Transmission to the Agricultural Sector in Poland. Sustainability, 16(16), 7072. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167072