Heritage as a Driver of Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case Study of the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How can heritage drive sustainable tourism development along the Darb Zubaydah pilgrimage route in Saudi Arabia?

- What economic benefits can sustainable tourism along the Darb Zubaydah route bring to the local communities?

- How can the preservation of the heritage of the Darb Zubaydah route contribute to the cultural identity of the local communities?

- Integrating cultural heritage into tourism development plans along the Darb Zubaydah route will enhance cultural and natural heritage preservation, promote linear “slow tourism”, and lead to the discovery of local culture and historical sites, bringing greater cultural awareness.

- Sustainable tourism development along the Darb Zubaydah route will significantly contribute to the local economy by creating job opportunities, boosting local businesses and promoting cultural events and activities. This potential for job creation can encourage and motivate the local communities.

- Preserving the Darb Zubaydah route’s heritage can significantly contribute to the cultural identity of local communities by maintaining and revitalizing historical landmarks, which serve as tangible connections to their past. These preserved sites foster a sense of pride and continuity, reinforcing the community’s historical narrative and cultural traditions.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Pilgrimage Routes in Saudi Arabia

- The Pilgrim Road from Syria: This road connected Damascus to Makkah, passing through the province of Tabuk in Saudi Arabia, and Madain Saleh (Hegra), an archaeological site in the Al-Ula area, today an important tourist destination in the Kingdom rich in cultural heritage. This route is referred to as the Ottoman or Shami (Levant) route.

- The Pilgrim Road from Egypt: The African road used by pilgrims from Egypt, Morocco, Andalusia, Sicily, and various areas of Africa. Along this route are rock carvings by pilgrims as a reminder of their Hajj journey.

- The Pilgrim Road from Yemen: This road came from southern Saudi Arabia. Three routes, one coastal, one internal, and one primary, crossed the province of Asir in Arab territory until the city of Taif and then Makkah. Along the way, several villages were where pilgrims stopped.

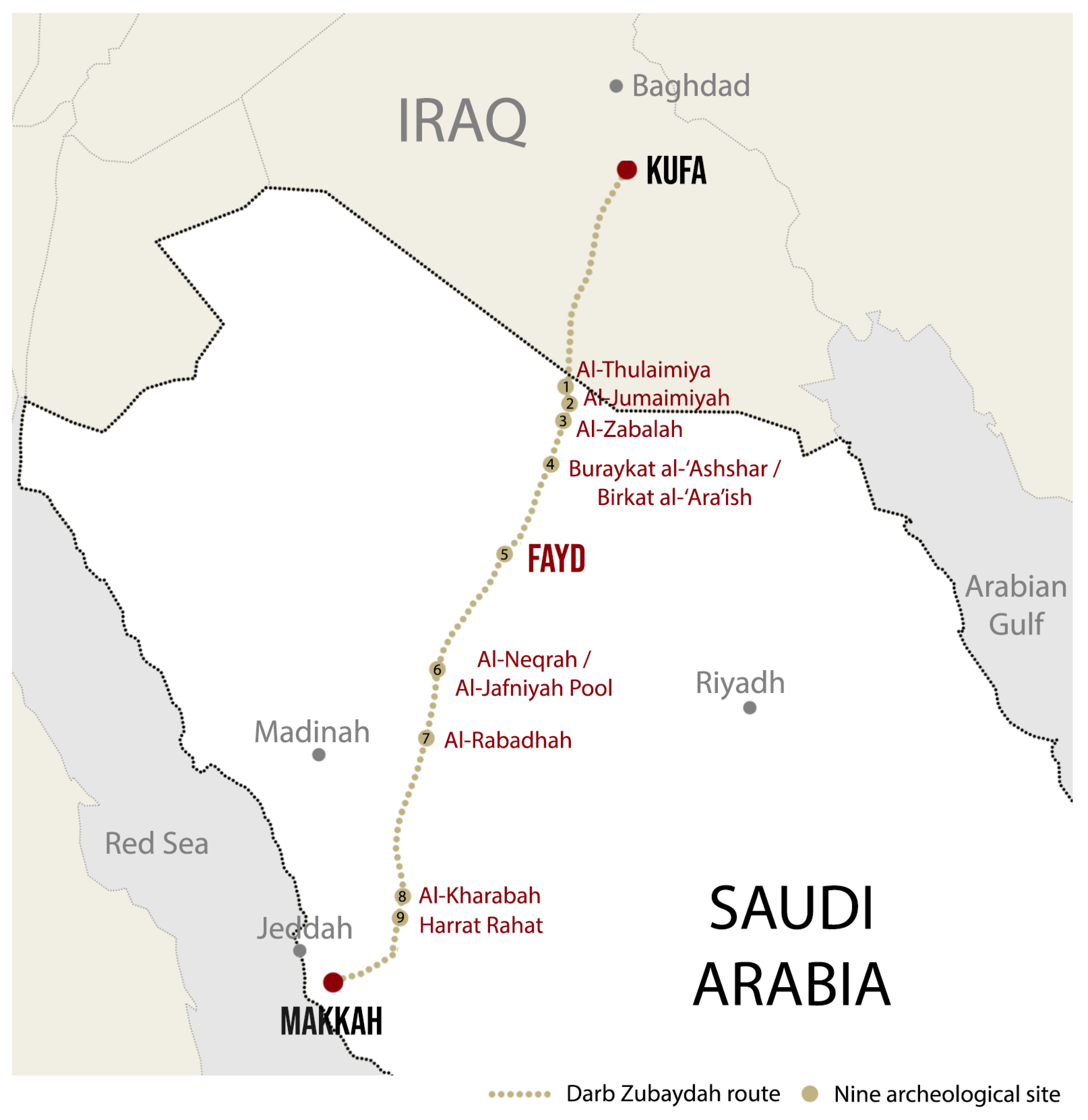

- The Pilgrim Road from Iraq: This road connected the city of Baghdad and Kufa in Iraq to Makkah, traversing the north of the Kingdom and its center, passing the vast and treacherous sands of the Empty Quarter, the largest sand desert in the world, before reaching the Holy City. This ancient route is known by the name Darb Zubaydah because it takes its name from Zubaydah bint Jafar, wife of the Abbasid caliph Harun Al-Rashid, for the remarkable charitable work she has supported along the Hajj route through the construction of numerous stations, canals, wells, forts, and mosques.

3. Methodology

3.1. Step 1: Pilgrim Data Record in Saudi Arabia

3.1.1. Annual Number of Hajj Pilgrims

3.1.2. Factors That Drive Pilgrims to Undertake a Pilgrimage Experience

3.1.3. Hostile Experiences and Safety Issue

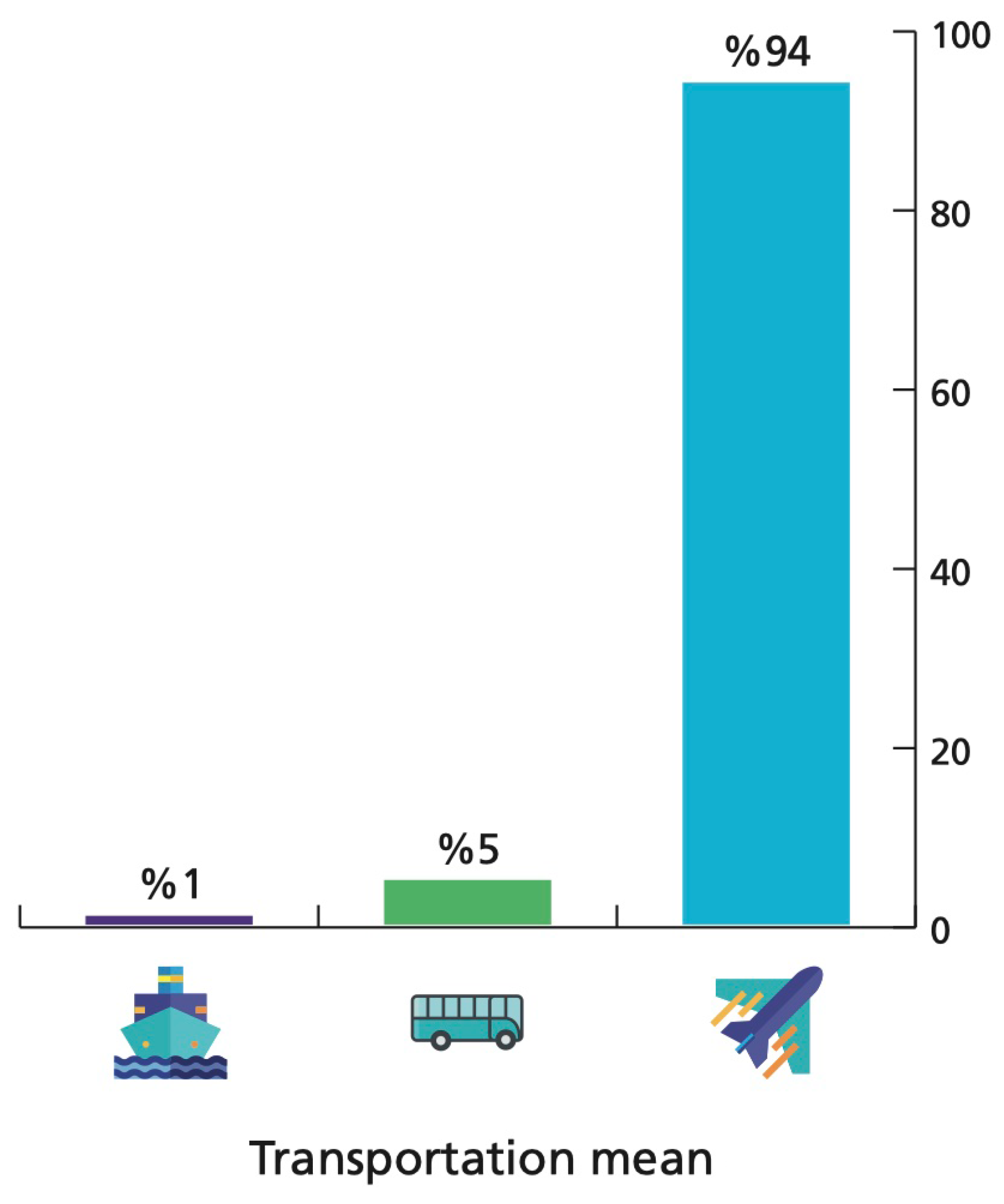

3.1.4. Impact of Modern Transportation on the Historical Pilgrimage Routes

4. Results

4.1. Step 2: Overview of the Case Study: The Darb Zubaydah Route

4.2. Step 3: Threats and Opportunities along the Route

4.3. Step 4: Heritage Sustainable Criteria

4.4. Step 5: Results Validation

- For the cultural development criteria, the strategic solutions focus on two sub-criteria: restoration and conservation and heritage programs. Restoration and conservation efforts include the preservation and maintenance of significant archaeological sites, such as fortresses, mosques, and wells, as well as the upkeep of pavements along the route. Heritage programs aim to enhance visitor engagement and education through the development of informative panels, guided tours, interactive exhibits, and educational facilities like cultural centers and museums [50]. These initiatives are designed to deepen visitors’ understanding of the historical and cultural significance of the route, highlighting the Abbasid era and other historical contexts. It is a unique experience to cross into a region rich in heritage. The main objective in reviving this cultural route is to achieve an exceptional visitor experience, rich in historical values and creative interaction with the cultural and environmental heritage of Darb Zubaydah.

- In terms of environmental development, the strategic solutions offer many benefits. They are divided into sustainable practices and environmental programs. Sustainable practices emphasize using natural energy sources, such as solar panels, for site operations and lighting and promoting water conservation and recycling. These practices not only reduce the environmental impact but also contribute to the sustainability of the route. Environmental programs focus on activating desert tourism activities that allow visitors to experience traditional social life while encouraging low-impact activities like hiking and camel riding. Additionally, promoting environmentally friendly transportation options, such as electric vehicles, and creating a desert science center for star watching are integral parts of the strategy. Implementing a linear greening solution along the path further supports environmental conservation. The goal is to integrate Darb Zubaydah culture with the natural environment into the daily lives of citizens and visitors alike.

- Spatial development is addressed through infrastructure network improvements and enhancements to accessibility and connectivity. Implementing a secondary infrastructure network with perpendicular roads to the main route allows visitors to access the pilgrimage route at various points, reducing the distance between stations. New stations have been added to facilitate shorter travel segments, with distances of 10 to 30 km. Developing a comprehensive site map and introducing smart technology, such as GPS-enabled apps, help visitors navigate different itineraries and cultural events on their phones [51]. Enhancements to accessibility and connectivity include establishing designated parking areas, developing public transportation options like shuttle services, improving connectivity between sites with pedestrian paths and bicycles, and creating alternative trails linking different stations.

- For economic development, the strategic solutions are categorized under local economy and tourism facilities. Promoting cultural events and festivals is essential for attracting visitors and boosting the local economy. Establishing a visitor fee system supports site maintenance, while workshops and activities highlighting cultural heritage provide economic opportunities for local communities. The financial impacts of the tourists can benefit the development of heritage sites and the residents financially [26,52]. Lighting along the road and in the archaeological sites will allow visitors to visit the archaeological sites at night and have a different perception of the site between day and night. The development of tourism facilities focuses on ensuring a comfortable and safe experience for visitors. This includes creating accommodation facilities such as traditional Bedouin-style tented camps to host tourists in an authentic space, allowing them to become closer to the local traditional culture and the desert landscape. Local shops and souq markets, spiritual and reflective spaces, health centers, and security posts will also be strengthened along the way.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moscatelli, M. Enhancement of cultural heritage tourism along the Darb Zubaydah pilgrimage route in Saudi Arabia. Fayd Oasis as a sustainable development scenario. In Proceedings of the IFKAD, Managing Knowledge for Sustainability, Matera, Italy, 7–9 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Hou, B.; Kong, X. The Practice Characteristics of Authorized Heritage Discourse in Tourism: Thematic and Spatial. Land 2024, 13, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade Suárez, M.; Caamaño Franco, I.; Sousa, A.Á. A pilgrim but a tourist too: Re-examining the contemporary links. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potsiou, C.; Ioannidis, C.; Soile, S.; Boutsi, A.-M.; Chliverou, R.; Apostolopoulos, K.; Gkeli, M.; Bourexis, F. Geospatial Tool Development for the Management of Historical Hiking Trails—The Case of the Holy Site of Meteora. Land 2023, 12, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, L.; Trillo, C.; Makore, B.N. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development Targets: A Possible Harmonisation? Insights from the European Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerario, A. The Role of Built Heritage for Sustainable Development Goals: From Statement to Action. Heritage 2022, 5, 2444–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vythoulka, A.; Delegou, E.T.; Caradimas, C.; Moropoulou, A. Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece. Land 2021, 10, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaberi, Z.A.; Hasan, S.A. Reviving the cultural route and its role in the sustainability of historical areas—Kerbala as a case study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. International Cultural Tourism Charter. Managing Tourism at Places of Heritage Significance (1999). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/INTERNATIONAL_CULTURAL_TOURISM_CHARTER.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Brooks, G. Heritage as a driver for development: Its contribution to sustainable tourism in contemporary society, 2012. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 17th General Assembly, Paris, France, 27 November–2 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO—United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Florence Declaration: Culture, Creativity and Sustainable Development. Research, Innovation, Opportunities. In UNESCO World Forum on Culture and Cultural Industries, 3rd ed.; UNESCO: Florence, Italy, October 2014; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230394 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Moscatelli, M. Preserving Tradition through Evolution: Critical Review of 3D Printing for Saudi Arabia’s Cultural Identity. Buildings 2024, 14, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, L.D.; Mazzetto, S. Comparing AlUla and The Red Sea Saudi Arabia’s Giga Projects on Tourism towards a Sustainable Change in Destination Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Tourism, National Tourism Strategy. Available online: https://mt.gov.sa/about/national-tourism-strategy (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Mazzetto, S. Sustainable Heritage Preservation to Improve the Tourism Offer in Saudi Arabia. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast Company. Saudi Arabia Will Host 30 Million Pilgrims by 2030. This Is How Technology Will Help. Available online: https://fastcompanyme.com/news/saudi-arabia-will-host-30-million-pilgrims-by-2030-this-is-how-technology-will-help/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Pilgrim Experience Program. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/vision-2030/vrp/pilgrim-experience-program/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Moscatelli, M. Cultural identity of places through a sustainable design approach of cultural buildings. The case of Riyadh. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1026, 012049. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/1026/1/012049 (accessed on 22 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Affiliate Members Global Reports, Volume Twelve—Cultural Routes and Itineraries; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://catedratim.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/omt-2015-global_report_cultural_routes_itineraries.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Tsironis, C.N. Pilgrimage and Religious Tourism in Society, in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Paradigmatic Focus on ‘St. Paul’s Route’ in the Central Macedonia Region, Greece. Religions 2022, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATTA. North American Adventure Travelers: Seeking Personal Growth, New Destinations and Immersive Culture; Adventure Travel Trade Association: Seattle, WA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Green Pilgrimage. Policy Peer Review of European National and Regional Policies on Pilgrimage Routes and Cultural Trails Protecting and Enhancing Cultural and Natural Heritage through Sustainable Tourism. Available online: https://projects2014-2020.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1542361094.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Collins-Kreiner, N. The geography of pilgrimage and tourism: Transformations and implications for applied geography. Appl. Geogr. 2010, 30, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Pimenta, E.; Gonçalves, F.; Rachão, S. A new research approach for religious tourism: The case study of the Portuguese route to Santiago. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2012, 4, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlizos, S.; Kosta, E. Designing Cultural Routes in the Region of Sparta, Peloponnese: A Methodological Approach. In Proceedings of the 6th UNESCO UNITWIN Conference, Leuven, Belgium, 8–12 April 2019; Available online: https://ees.kuleuven.be/unitwin2019 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Olsen, D.H.; Trono, A. Religious Pilgrimage Routes and Trails: Sustainable Development and Management; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- GASTAT—General Authority for Statistic. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/news/532 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Hassan, T.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, O. Segmentation of Religious Tourism by Motivations: A Study of the Pilgrimage to the City of Mecca. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayal, G. The personas and motivation of religious tourists and their impact on intentions to visit religious sites in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2023, 9, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božic, S.; Spasojević, B.; Vujičić, M.D.; Stamenkovic, I. Exploring the Motives of Religious Travel by Applying the Ahp Method—The Case Study of Monastery Vujan (Serbia). Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2016, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois-González, R.C.; Santos, X.M. Tourists and pilgrims on their way to Santiago. Motives, Caminos and final destinations. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2015, 13, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Galzacorta, M.; Guereño-Omil, B.; Makua, A.; Iriberri, J.L.; Santomà, R. Pilgrimage as Tourism Experience: The Case of the Ignatian Way. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2016, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaium, A.; Al-Nabhan, N.A.; Rahaman, M.; Salim, S.I.; Toha, T.R.; Noor, J.; Hossain, M.; Islam, N.; Mostak, A.; Islam, M.S.; et al. Towards associating negative experiences and recommendations reported by Hajj pilgrims in a mass-scale survey. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, H.T.; Abdou, A.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Nor-El-Deen, M.; Salem, A.E. The Impact of Religious Tourists’ Satisfaction with Hajj Services on Their Experience at the Sacred Places in Saudi Arabia. GeoJournal Tour. Geosites 2022, 43, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaths during Annual Hajj in Saudi Arabia Underscore Extreme Heat Dangers. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/06/25/deaths-during-annual-hajj-saudi-arabia-underscore-extreme-heat-dangers (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Hajj Deaths Highlight the Need to Keep Pilgrims Safe. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/opinion/editorial/2024/06/25/hajj-pilgrims-heat-saudi-arabia-travel-safety/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Climate Change Has Made the Hajj Pilgrimage More Risky. Available online: https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2024/06/climate-change-has-made-the-hajj-pilgrimage-more-risky (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- GASTAT—General Authority for Statistic, Hajj Statistics 2019–1440. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/haj_40_en.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Jaffer, I. Spiritual Motivation for Religious Tourism Destinations. In Spiritual Religious Tourism. Motivations and Management, 2nd ed.; Dowson, R., Yaqub, J., Raj, R., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention. The Hajj Pilgrimage Routes: The Darb Zubaydah (Saudi Arabia), in Tentative Lists, Permanent Delegation of Saudi Arabia to UNESCO, 2022. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6577/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Gierlichs, J. Early Pilgrimage Routes to Mecca and Medina. In Roads of Arabia. Archaeological Treasures from Saudi Arabia; Franke, U., Gierlichs, J., Eds.; Wasmuth: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 208–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, J.M. Architectural ‘Influence’ and the Hajj. In The Hajj: Collected Essays; Porter, V., Saif, L., Eds.; British Museum: London, UK, 2013; pp. 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, A.; Ulrich, B. From Iraq to the Hijaz in the Early Islamic Period: History and Archaeology of the Basran Hajj Road and the Way(s) through Kuwait. In The Hajj: Collected Essays; Porter, V., Saif, L., Eds.; British Museum: London, UK, 2013; pp. 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomopoulou, E.; Delegou, E.T.; Sayas, J.; Vythoulka, A.; Moropoulou, A. Preservation of Cultural Landscape as a Tool for the Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: The Case of Mani Peninsula in Greece. Land 2023, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.O.; Baqawy, G.A.; Mohamed, A.S.M. Tourism attraction sites: Boasting the booming tourism of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2021, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egal, F.A. Major Oasis City Along the Pilgrimage Road from Baghdad, the Saudi Arabia Tourism Guide, 2017. Available online: https://www.saudiarabiatourismguide.com/fayd/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Cassalia, G.; Tramontana, C.; Ventura, C. New Networking Perspectives towards Mediterranean Territorial Cohesion: The Multidimensional Approach of Cultural Routes. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, A. Museum Inside the Territory. The Museo Diffuso as a Tool for Cultural Infrastructure of Places. The Case of the Lybian Coastal Road. 2018. Available online: https://iris.unibas.it/handle/11563/167134 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Allawi, A.H. Towards smart trends for tourism development and its role in the place sustainability- Karbala region, a case study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C. Developing religious tourism in emerging destinations: Experiences from Mtskheta (Georgia). Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2011, 7, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, P.; Roders, A.P.; Colenbrander, B. Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarrán, J.D. Tourism Development and Urban Landscape Conservation in Rural Areas: Opportunities and Ambivalences in Local Regulations—The Case of Spain. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumaran, K.; Mohammadi, Z.; Azzali, S.; Eijdenberg, E.L.; Donough-Tan, G. Transformed landscapes, tourist sentiments: The place making narrative of a luxury heritage hotel in Singapore. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 18, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehbi, B.O.; Hoskara, S.Ö. A Model for Measuring the Sustainability Level of Historic Urban Quarters. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 715–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths. Heritage 2019, 2, 938–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.A.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Croitoru, I.M.; Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R. Rural Tourism in Mountain Rural Comunities-Possible Direction/Strategies: Case Study Mountain Area from Bihor County. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Archeological Site | Coordinates | Brief Description of the Representative Cultural Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Al-Thulaimiya | 29°37′29.83″ N 43°36′46.09″ E | Historical station, located about 10 km from the Saudi-Iraq border. It features a well-preserved 32 m diameter circular basin with a thick wall and a large staircase for water access, along with a reservoir, mosque, and other structures. |

| 2 | Al-Jumaimiyah | 29°36′20.03″ N 43°36′13.48″ E | Pilgrim station 14 km east of Rafha, Saudi Arabia. It features a well-preserved 30 × 30 m rainfed basin, a dry dug well, and old foundation remains. The basin is 3.45 m deep with eleven flights of steps descending from the eastern wall. Nearby, 1 km south, are the ruins of a possible fortress or caravanserai. |

| 3 | Al-Zabalah | 29°23′55.80″ N 43°33′43.80″ E | Zabalah, 38 km south of Rafha, was a key pilgrim station known for its abundant water and vibrant trade during Hajj. Spanning 2 × 1 km, it had a fortress, mosque, and three large water tanks, including a restored 40 × 45-m tank. The site also features hundreds of deep wells still in use. South of the wadi are the ruins of a 35 × 35-m fortress with round towers and an enclosed court, alongside house ruins. |

| 4 | Stretch of the paved route between Buraykat al-‘Ashshar and Birkat al-‘Ara’ish | 28°28′53.16″ N 43°19′49.24″ E | Darb Zubaydah’s road infrastructure, spanning approximately 40 km from Buraykat al-Ashshar to Birkat al-‘Ara’ish, features stone pavements of varying widths (2–4 m). This Abbasid-era achievement aimed to facilitate pilgrim travel across the soft sands of the Nefud desert. |

| 5 | Fayd | 27°7′13.20″ N 42°31′20.73″ E | Fayd, located midway between Kufa and Makkah, was strategically vital on the Darb Zubaydah. During the Abbasid era; it served as a crucial station and administrative center for pilgrims, offering storage for supplies. Fayd’s historical significance predates Islam, evidenced by its well-known fortress and ancient wells. Fayd was described as a fortified town dependent on pilgrim trade. The ancient monuments lie north of modern Fayd, with numerous wells and two large sand-filled reservoirs nearby. The original Pilgrim Route, now marked by cleared paths with low stone walls, passed nearby. |

| 6 | Al-Neqrah—Al-Jafniyah Pool | 25°32′41.70″ N 41°35′14.80″ E | Ma’dan An-Neqrah, north of Jabal Ma’dan, historically mined copper and served as a key point on the Darb Zubaydah pilgrimage route. It featured a palace, mosque, road markers, and pools like the Aljfnyh Pool, facilitating pilgrims’ journeys and reflecting its multifaceted past. |

| 7 | Al-Rabadhah | 24°37′51.70″ N 41°17′23.39″ E | Prosperous pilgrim station, inhabited by Bedouins and equipped with accommodations and water facilities. Al-Harbi documented a fortress, two mosques, and two reservoirs, circular and square. Archaeological excavations have revealed valuable ceramics and interior decorations reminiscent of the imperial Abbasid style. |

| 8 | Al-Kharabah | 22°11′41.88″ N 40°50′3.05″ E | Situated in a depression in Sahl Rakbah, it features two large and well-maintained reservoirs. An aqueduct from Wadi al-Aqlq supplies water to these tanks. The first tank is rectangular, 36 × 28 m with stepped sides and access steps, while the second tank is circular, 54 m in diameter and stepped, with a domed room between them likely for station caretakers. |

| 9 | Harrat Rahat, stretch of the cleared route between Sufayna and Birket Hadha | 22°10′27.68″ N 40°47′10.68″ E | The road from Birkat Al-Shihiyya to Birkat Hamad cuts through rocky terrain where Abbasid engineers cleared large stones to form roadside walls. It spans about 18 m wide and continues southward through volcanic harrat Rahat, winding around large boulders with smaller rocks used for curb-walls, widening to around 20 m in the most challenging areas. |

| Heritage Sustainable Criteria | Criteria Definition | Connection to ICOMOS Charter |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural development | Integration of the pilgrimage route with the local culture, aiming to preserve and reveal the rich cultural heritage along the trail. It involves showcasing cultural landmarks to create a meaningful experience for tourists and pilgrims. | The ICOMOS Charter emphasizes the conservation of cultural heritage and its integrity, promoting public awareness and understanding. This criterion aligns with the Charter by ensuring that cultural landmarks are preserved and presented to enhance visitors’ appreciation and understanding of the site’s historical and cultural significance. |

| Environmental development | Focused on the sustainable management and conservation of natural resources along the pilgrimage route, this criterion ensures that tourism activities do not harm the environment. It includes measures for promoting eco-friendly practices to maintain the natural beauty and health of the region. | The ICOMOS Charter advocates for sustainable tourism practices that protect and conserve natural and cultural environments. This criterion aligns with the Charter by promoting eco-friendly practices that minimize environmental impact, ensuring that the natural resources along the pilgrimage route are conserved and maintained for future generations. |

| Spatial development | Physical planning and infrastructure improvements are needed to support the pilgrimage route. It includes the development of accessible pathways, accommodation, amenities, and transportation facilities that enhance the overall experience while maintaining the integrity of historical sites and landscapes. | The ICOMOS Charter stresses the importance of integrated management in heritage and tourism, ensuring that infrastructure developments support heritage conservation. This criterion aligns with the Charter by improving infrastructure to facilitate visitor access and enhance their experience while preserving the historical and cultural integrity of the pilgrimage route. |

| Economic development | This criterion aims to boost local economies through tourism by creating job opportunities and fostering economic activities related to the heritage route. It ensures that the financial benefits of tourism are distributed equitably among local communities, contributing to their sustainable growth and development. | The ICOMOS Charter highlights the need for tourism to benefit local communities economically, supporting their social and economic well-being. This criterion aligns with the Charter by fostering economic development that benefits local communities, ensuring that the financial gains from tourism are shared fairly, leading to sustainable growth. |

| Heritage Sustainable Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Strategic Solutions to Enhance the Darb Zubaydah Pilgrimage Route | Common Elements of Security and Risk Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural development | Restoration and Conservation |

|

|

| Heritage Program |

| ||

| Environmental development | Sustainable Practices |

| |

| Environmental Program |

| ||

| Spatial development | Infrastructure network |

| |

| Accessibility and Connectivity |

| ||

| Economic development | Local Economy |

| |

| Tourism Facilities |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moscatelli, M. Heritage as a Driver of Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case Study of the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167055

Moscatelli M. Heritage as a Driver of Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case Study of the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167055

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoscatelli, Monica. 2024. "Heritage as a Driver of Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case Study of the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167055

APA StyleMoscatelli, M. (2024). Heritage as a Driver of Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case Study of the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route. Sustainability, 16(16), 7055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167055