1. Introduction

With the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the United Nations laid the foundations for the organization of public services. Although it does not explicitly define public services, there are nevertheless relevant articles that refer to aspects of the public sector, such as Article 21: “(2) Everyone has the right to participate on equal terms in the public functions of his country” and Article 17: “(1) Everyone has the right to own property alone or in community with others; (2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property” [

1]. Based on this document, every service should have a social and territorial dimension that guarantees equal access to essential goods at reasonable prices and tariff redistribution for free access throughout the territory [

2]. Although there are different points of view and approaches, public service can be defined as an activity of general interest managed by a public body based on common law rules. In other words, it is a public activity that is essential for the satisfaction of basic needs, such as health, social security, education, communication, transportation network, sanitation, access to water and electricity, etc., except the so-called sovereign activities linked to the sovereignty of the State [

3].

Given the changing needs of citizens in a changing society, public institutions are challenged to continuously improve the sustainability performance of public services [

4,

5]. To this end, metrics are needed that can demonstrate the impact of such activities from an economic, environmental, and social perspective [

6]. The integration of sustainability into decision-making dates to the Brundtland Report of 1987, which emphasized the three dimensions of sustainability: environmental, economic, and social. More recently, the European Union’s law on the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) requires all large companies and all listed companies to disclose information on their risks and opportunities arising from social and environmental issues and on the impact of their activities on people and the environment [

7]. One way to measure these consequences can be to use environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investment criteria. These ESG criteria are a set of standards relating to the behavior of a company and are used as an analytical tool with which companies can measure their corporate social responsibility (CSR), to comply with the objectives of sustainable development [

8].

From a methodological perspective, the life cycle approach, and in particular the life cycle assessment (LCA) method, has proven to be promising for assessing the environmental sustainability of products and the environmental impact of public services [

9]. However, the study of the social dimension of public services, also known as social life cycle assessment (S-LCA), is still in its infancy [

10,

11]. In 2020, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) published a guidance document that sets out the methodological framework for S-LCA. The document guides the stakeholder categories for which the social impacts of a product or organization must be assessed and the subcategories of potential social impacts to be considered [

12]. The S-LCA framework described in the guidelines comprises four steps, shown in

Figure 1: Define the objective and the context of the study, which can be a product, a service, or an organization. The definition of stakeholder categories is followed by the collection and selection of relevant data (social life cycle inventory). This is followed by the assessment of potential social impacts based on indicators and specific impact subcategories and the interpretation of the results to draw conclusions and recommendations to improve social performance. The S-LCA workflow then consists of the description of all the activities that need to be carried out to perform an analysis.

In this approach (

Figure 1), stakeholders are defined as groups or individuals who may be affected by or have an interest in an organization’s activities, including employees, surrounding communities, supply chain partners, customers, children, and society in general. The subcategories of impact are described as socially relevant topics or characteristics that are assessed using impact indicators. These subcategories are linked to stakeholder groups and organized in a way that simplifies implementation and ensures the completeness of the S-LCA framework. Finally, performance indicators are described as tools that can be used to measure the social impact of an organization’s activities over the entire life cycle of its products or services. They are directly related to the product life cycle inventory and may differ depending on the context of the study. The assessment of each subcategory of impact may require the use of multiple indicators, the selection of which will depend on the specific issues and concerns highlighted by the S-LCA analysis.

In 2021, UNEP also published a second document that presents methodological guidance for the definition of inventory indicators that can potentially be used in the assessment of social performances [

13]. Despite such documents, the identification of stakeholder categories, the definition of subcategories, and the establishment of performance indicators is still an open field of research. This is confirmed by the remarkable increase in the number of S-LCA papers that concern S-LCIA methodological approaches (hereafter, methodological approaches) and case studies [

11,

14,

15,

16], on products, services, and organizations. Also, nine case studies, six related to the S-LCA of products, two to the social organizational life cycle (S-OLCA) of organizations, and one S-LCA of a private service were published in the Pilot Projects [

17].

Despite the growing interest, there is currently no work addressing the application of S-LCA to public services, except for a single case study on the social impact of mobility services in Berlin [

11]. This case study on mobility services in Berlin highlights the challenges and opportunities associated with assessing the social impact of public services. It examines the impact of mobility policies on social inclusion, access to services for people with reduced mobility, and the impact on local employment. The study then underlines the need to develop specific indicators to highlight the social impact of public services, considering the local context and the needs of communities. This public service case study is probably unique due to its novelty. Although it helps to fill an important gap in the S-LCA literature, it nevertheless remains limited; hence, the urgent need to research this sector.

This article aims to define a research framework through a systematic literature review to support and guide future research on public service S-LCA. The need for this study arises from the fact that public services are sparsely addressed in the literature on S-LCA, despite their importance in providing essential services to society. To achieve this goal, the literature review is divided into three parts to better highlight the aspects that could be useful for the S-LCA of public services.

- –

Section 2 describes the methodology used to develop a research framework for S-LCA of public services, explaining the research protocol, the software used, the process of data review, and the analytical technique chosen to identify research gaps and opportunities.

- –

Section 3 presents the qualitative and quantitative results, focusing on the stakeholder categories, impact subcategories, and indicators specific to public services (hereafter referred to as components) that emerge from the literature and are essential for a complete S-LCA.

- –

Finally,

Section 4 discusses the results obtained and the various conclusions drawn about the research objectives as well as the challenges or limitations in operationalizing S-LCA applications for public services.

4. Discussion

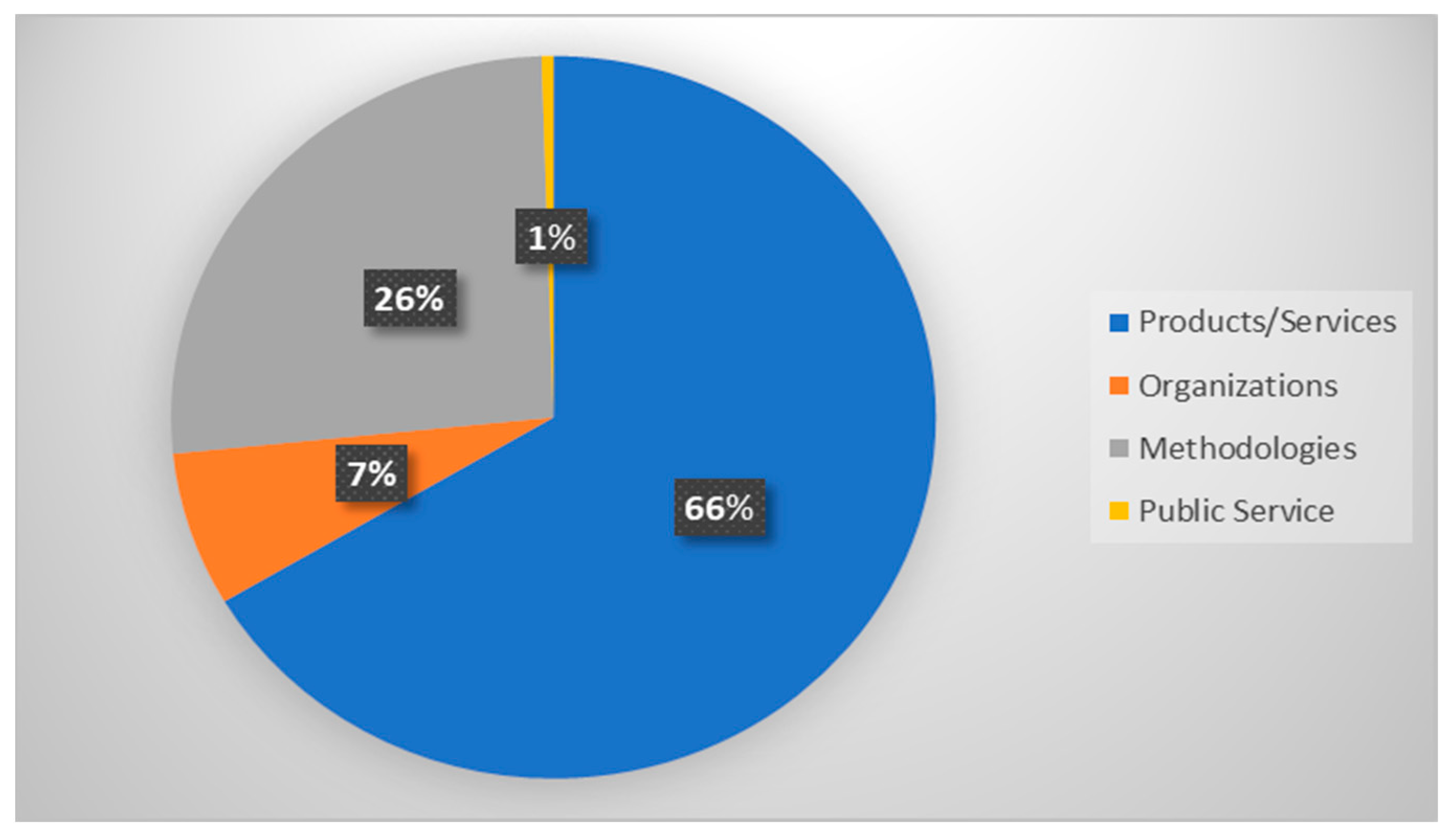

This work identified 222 articles on S-LCA published in 94 journals in the last ten years (2013–2022). One hundred sixty-nine articles concerned case studies, of which 67% were on S-LCA of products/services (including the only existing case study on public services) and 7% on organizations (SO-LCA), while fifty-three articles (26%) examined methodological issues. The results show that studies have mainly focused on case studies and methodological advancements, highlighting the continued interest in this topic as it remains a growing area of methodological inquiry. This growth is also justified by the collaboration between the authors and various journals that are particularly interested in methodological advances in S-LCA. Although not directly related to public services, the fact that it is an open topic leaves room for interest and further exploration in this area.

In the detailed analysis, only one study related to public services was found that applies S-LCA according to the UNEP guidelines [

11]. The identified study concerns the use phase of public transportation in the city of Berlin. Although this is the only actual case to be considered in the context of public services, it nevertheless provided a starting point for the development of a framework for the S-LCA of public services. The information contained in this study was combined with the information from other studies on public services dealing with different aspects of S-LCA. These include the identification of stakeholder categories, subcategories of impacts, and performance indicators for public services by Erauskin-Tolosa et al. [

30] and the systematic literature on the social assessment of municipal waste management systems from a life cycle perspective [

29]. Other studies analyzing public services without a focus on S-LCA also provide information on the type of direct actors and the type of social aspects involved [

35,

36,

37].

However, the S-LCA literature analyzed also contains strengths, such as the large number of registered studies (222) and the various reviews (94), which indicate a continuing interest in this area, suggesting a solid research base; the number of case studies (169) shows generally a practical orientation of the research, allowing S-LCA methods to be applied and tested in real contexts; methodological advances (53), showing a commitment to improving and refining different approaches to social impact assessment; and finally, the collaboration between researchers and journals indicates a collaborative and dynamic research environment in the field of S-LCA. However, this literature also contains weaknesses, such as the lack of studies on public services, which limits the understanding of social impacts in this sector; the diversity of methods and frameworks used in the different studies may lead to limited comparability of research, making it difficult to generalize the results. Thus, there is a need to promote more focused research on public services by developing more standardized frameworks and promoting a transdisciplinary approach.

First of all, the results of the analysis of the 10 selected articles show that the studies follow the main methodological elements required for the development of an S-LCA and SO-LCA [

11,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36], including the data recommendations (UNEP (2020), SHDB and PSILCA, but they also follow the LCA approach [

30]. However, it is important to make some clarifications about both approaches. The LCA approach is methodologically based on the ISO14040-2006 standard [

38], which sets out the principles and framework for conducting a life cycle assessment of a product or service from the extraction of raw materials to the end of its life. It includes phases such as the definition of the object of investigation, the life cycle inventory, the impact assessment, and the interpretation of the results. An environmental perspective is adopted, focusing on indicators such as greenhouse gas emissions, air and water pollution, resource consumption, etc. The S-LCA approach is based on life cycle thinking and draws on the UNEP Guidelines (2020) to structure its assessment. It draws on the principles of LCA but adapts the methodology to consider social aspects and assess the social impact on all different stakeholders. It adopts a social perspective, focusing on indicators such as working conditions, equal opportunities, workers’ rights, community participation, freedom of association, etc. Both approaches then involve a different process in terms of implementation and enforcement. Therefore, the main framework of LCA including the four phases is considered when using the results obtained in this study [

11,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Figure 5 provides a further breakdown and adaptation of the LCA framework to ensure its correct application in the S-LCA of public services.

The results also revealed 17 stakeholder categories, 74 subcategories of impacts, and 178 indicators that could be proposed in the case of public services, excluding those that are not directly related to public services. Although the identified components mostly concern products/services and organizations, there is a high probability that they are linked to one of the many types of public services (health, social security, transport network, education, waste management, etc.) that are essential to meet the basic social needs of citizens [

3]. If you specify the aim of each study and the different methods of impact assessment in the literature review, it is easier to select areas to be investigated depending on the aim of the study and to focus on less researched aspects such as health services, education, transportation, sanitation, etc. Secondly, highlighting the impact assessment methods can also help to emphasize the most-used method in S-LCA work, such as the type I approach performance assessment, which can also be used in public services, for example, to measure the performance of a municipality, a health facility, a transport system, etc.

It is important to keep in mind that in the proposed framework for the S-LCA of public services, based on the results obtained, the public service is considered a “product”, where the “product” is represented by the different services provided to the community. Therefore, the proposed stakeholder categories, subcategories of impacts, and performance indicators need to be applied only if they are consistent with the objective and scope of the defined study, with the specific public service under consideration. When applying the methodology, it is important to check whether the proposed components are also consistent with the specifics of the UNEP Guidelines (2020).

The function of a specific public service can help to identify the actors involved, based on those identified in an S-LCA study on a product (not a public service) that fulfills the same function. For example, in the S-LCA studies that analyzed waste management, the actors include formal and informal sector employees (recyclers, collectors, resellers, etc.), who can also apply to waste management as a public service. The same approach applies to the subcategories and indicators.

It is also necessary to consider issues of adaptability of the S-LCA framework for public services in different contexts, such as:

- –

Recognizing contextual and cultural diversity, which consists of acknowledging that public services operate in different political, cultural, economic, and social environments. Further, the effective application of the S-LCA framework should take into account each context, which presents unique challenges and specific opportunities depending on the continent, country, and city.

- –

Consideration of government systems and public policy, which includes an examination of government structures, decision-making processes, and public policy objectives. Consideration of this review would ensure that the S-LCA framework we wish to introduce is consistent with local priorities and requirements.

- –

Integration of local perspectives, i.e., consultations with all local stakeholders such as staff, service users, community representatives, and policymakers. Including these local perspectives will help to understand the values, expectations, and concerns specific to the local context.

- –

Flexibility in developing indicators and methodological approaches that needs to be adapted to different contexts. For example, when we define indicators for workers’ rights, these may vary according to local practices and laws. It is therefore necessary to define general indicators and leave room for adaptation to take local specificities into account.

The interactive relationships among the components of public services proposed for the S-LCA with public services are necessary to understand how the different social aspects influence each other. Stakeholders such as local communities, users, and employees can have a direct impact on subcategories such as accessibility of services, environmental preservation and promotion of human rights, social inclusion, and occupational health, which in turn influence performance indicators measuring the effectiveness of public services such as service utilization rates by marginalized groups, the number of occupational accidents or diseases, and the sustainability indicators. This relationship shows how improvements in one area can have a positive impact on other areas, while shortcomings in one area can hurt the overall social performance of the services provided. There can also be a feedback loop between the indicators and stakeholders, in the sense that the indicators can be used to engage stakeholders in discussions about improving public services, for example. In turn, stakeholders can ask for specific indicators to measure the social aspects that are important to them. For example, access to public services can have a positive impact on social inclusion and employment, while unsatisfactory working conditions can lead to deterioration in the quality of services, which in turn can hurt access to services and social inclusion. Finally, public policy could influence these components because it sets the framework within which public services operate, which could have a direct impact on the components. For example, policies aimed at reducing social inequalities and discrimination could have an impact on the way public services are designed, implemented, and evaluated.

At the methodological level, the work of Jannatul et al. could also contribute to the interactions among components in the following ways: first, through the systemic approach, as the integrated methodology discussed in the article promotes a systemic approach that considers the interactions between the different aspects of the life cycle. In the context of the S-LCA of public services, this could mean considering how operational decisions affect local communities, society, employment equity, etc. Secondly, the optimization and simulation of processes consist of assessing the impact of process changes before they are implemented. In the case of public services, this could enable the simulation of the impact of new services or even changes to existing services on social conditions, by optimizing public services for improved efficiency and sustainability, taking into account the social impact on stakeholders [

39].

Finally, the indicators proposed for the case of S-LCA of public services have been identified, as mentioned, from a public services perspective. If they need to be refined for the different public services, one must rely on a specific case based on its context and local circumstances. However, in the context of this study, they can be refined in a general way. We based this on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were adopted by the United Nations in 2015. This is because they provide a global framework for collective action to promote sustainable development and solve global challenges. These goals therefore cover a wide range of areas and looking at the classification of indicators identified with this approach would allow these fundamental indicators to be considered by all. As an integral part of the state and its local authorities, public services play an essential role in the implementation of the SDGs. They are directly involved in the provision of essential services such as education, health, clean water and sanitation, energy, transportation, and social services, all of which are key elements in achieving the SDGs. The analysis did not consider the 17 SDGs but identified the first four Sustainable Development Goals, which particularly emphasize the important social aspects related to public services. The analysis therefore identified firstly SDG 1 (Eradicating poverty in all its forms everywhere) because poverty is a real social problem that can prevent access to education, health, adequate housing, and other essential services. Second, SDG 2 (End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture) because inadequate access to safe and nutritious food can lead to real health problems. Third, SDG 3 (Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages) because health is a key element of social well-being, and inequalities can lead to social divisions and limit the opportunities of individuals and communities. Finally, fourth, SDG 4 (Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all), because education is a pillar of social development and inclusive and equitable education is crucial for reducing inequalities and promoting a just and informed society [

40].

This analysis allowed us to identify public services such as education, health, transportation, and housing. The proposed indicators for public services can therefore be classified as follows:

- –

In education services, indicators such as teaching hours and training, health and safety of teachers, gender pay gap, employee participation, equal opportunities, prevention of discrimination, public expenditure on education, female illiteracy rate, male illiteracy rate, total illiteracy rate, female adolescent illiteracy rate, male adolescent illiteracy rate, total adolescent illiteracy rate, investment in technology, etc., can be considered.

- –

In healthcare, indicators such as healthcare expenditure, sanitation, drinking water supply, number of workers affected by natural disasters, employee participation, equal opportunities, prevention of discrimination, birth rate, infant mortality rate, social security expenditure, violations of labor laws and regulations, fatal accidents, non-fatal accidents, gender pay gap, investment in technology, etc., can be considered.

- –

Transportation services can consider indicators such as the number of transport points, number of passengers, fatal and non-fatal traffic accidents, fares, number of jobs created, accident rate, employee participation, equal opportunities, prevention of discrimination, investment in technology, pollutant emissions (NOx, PM10, PM2.5, SO2), carbon footprint (GWP100), etc.

- –

For housing services, indicators such as green and open spaces per capita, noise exposure above 65 dB, average noise emissions, level of population participation, infrastructure efficiency, occupancy of infrastructure space, urban planning, taxes per capita, net migration rate, international migrants, international migrant workers, employee participation, equal opportunities, prevention of discrimination, pollutant emissions (NOx, PM10, PM2.5, SO2), carbon footprint (GWP100), investment in technology, etc., can be taken into account.

Limitations

As mentioned above, the main limitation of this study is the lack of scientific studies in the case of S-LCA of public services. This might question the reliability of the whole sample and the related technical analysis for the development of the framework for the S-LCA of public services. However, the results of several scientific studies [

11,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36] combined with those of the only identified study on public services provide sufficient information on methods and developmental steps, and could significantly affect the validity of our approach. It is therefore essential that future studies in the field of S-LCA also focus on specific cases of public services that represent a crucial lever for the well-being of the population at the social level. This is because assessing the potential risks associated with these services could help to improve the living conditions of all those involved.

There is also a limitation in terms of databases, as the available databases have not been developed with public services in mind. Therefore, particular attention should be given to the quality of the specific data collected on the ground as it reflects the reality of the public service provided. Subsequently, these data could be enriched with the help of databases that also document the public sector, such as those of the ILO, the World Bank, UNICEF, etc. The impact of the limitations on practical application may depend on aspects such as the reliability of the data, as the lack of scientific studies specifically addressing the S-LCA of utilities could call into question the reliability and objectivity of the data as well as the technical analyses used to develop the assessment framework. The lack of scientific research could also limit the development of robust and adapted methodologies for public services. And if the results are based on a limited and unrepresentative sample, this could influence the decision-making of policymakers. To remedy this, it is necessary to promote and conduct additional research on specific cases of public services to enrich the knowledge base and improve the reliability of data; promote interdisciplinary collaboration between experts from different fields to develop adapted and contextualized methodologies; use secondary data from other sources or studies to complete the analyses, taking into account their validity and relevance; create platforms for knowledge exchange and sharing to facilitate collaboration and mutual learning among public service S-LCA actors; and, lastly, conduct pilot projects and test the proposed framework.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a systematic overview of the S-LCA literature and its methodological developments over the last ten years (2013–2022). To answer the question of how the results obtained can be linked to the case of public services, a qualitative and quantitative analysis of the data was carried out using the Web of Science and Scopus databases. In the quantitative analysis, the temporal evolution of scientific publications was highlighted, showing a significant increase from 2013 to 2022. The analysis also sheds light on the authors and their collaboration on methodological issues, as this is still an open topic. Finally, the major journals are also interested in new scientific trends in terms of topics and methods. The qualitative analysis revealed that different areas of S-LCA have been studied over the last ten years. It appears that most papers have focused on S-LCA of products/services (154), SO-LCA (14), and methodological issues (53), with only one case on public services. This was a limitation in achieving the objective due to the lack of scientific and field data, which are crucial in the development of performance indicators for public services. However, after analyzing the methodological issues, it was found that in the case of public services, 17 actors, 74 impact subcategories, and 178 indicators could be considered.

The analysis highlighted a lack of specific research in this area, underlining the need to close this gap. However, important methodological aspects necessary for the development of a social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) for public services were identified, especially the methodological approach, the identification of stakeholder categories and subcategories of impacts, and the development of indicators. In addition, the use of databases such as the ILO, World Bank, UNICEF, or PSILCA could facilitate access to the data needed to assess the social impacts of public services, as well as UNEP guidelines that could serve as methodological references for the development of a comprehensive approach to S-LCA of public services.

Based on these results, future work aims to apply the benefits of S-LCA in a specific case and develop specific performance indicators for this case. In addition, it is important to explore strategies to integrate field research and policy analysis to validate and refine the proposed framework. This could include in-depth case studies, stakeholder interviews, and a review of public policy related to the services under study. In addition, collaboration with practitioners and policymakers could provide practical knowledge and promote the application of research findings in real-world contexts. Finally, building partnerships with international organizations and S-LCA experts could help overcome methodological challenges and improve the rigor of the social impact assessment of public services.