Quartet of Sustainable Job Security, Job Performance, Organizational Commitment, and Motivation in an Emerging Economy: Focusing on Northern Cyprus

Abstract

1. Introduction

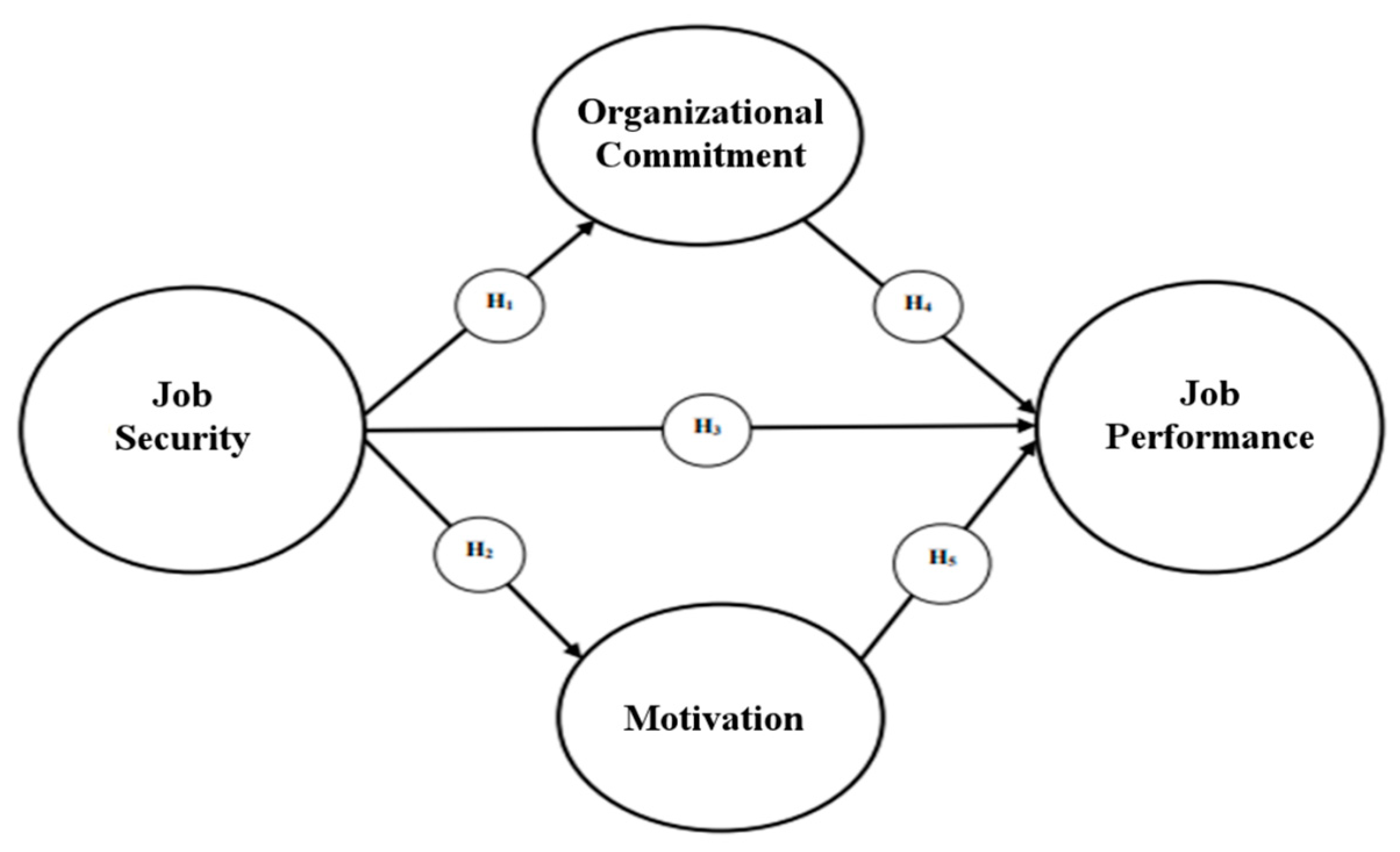

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

Control Variables

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Question Number | Item | Subquestion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subvariables | ||||

| Job Security Scale | Job Security Index | Question 1–6 | Your Job Security… What is your job security like in your organization? Indicate to what extent you agree with each statement by selecting the appropriate answer option. | Adequate Job Security |

| It’s Disturbing to Have So Little Job Security | ||||

| Excellent Job Security | ||||

| I’m stressed | ||||

| Positive | ||||

| Unacceptably Less | ||||

| Job Security Satisfaction | Question 7–12 | Your Future in the Institution… What is your job future like in your organization? Indicate to what extent you agree with each statement by selecting the appropriate answer option. | Hard to Predict | |

| Still | ||||

| Unknown | ||||

| My Job is Almost Guaranteed | ||||

| I Am Confident I Can Continue Here | ||||

| Uncertain | ||||

| Job Performance Scale | Task Performance | Question 1–4 | I think my professional knowledge is sufficient. | |

| I think I am competent in performing my job. | ||||

| I think my professional skills are sufficient. | ||||

| I think I am quick in doing my job. | ||||

| Contextual Performance | Question 5–20 | I think I am interested in my job. | ||

| I think I like banking. | ||||

| I think I am caring and helpful towards customers. | ||||

| I think my respect and love towards my customers is enough. | ||||

| I think I have care and attention in performing my job. | ||||

| I think I work in harmony and cooperation with my friends. | ||||

| I think there is complete respect and obedience towards managers. | ||||

| I think I am very satisfied with my job. | ||||

| I think I am honest and reliable. | ||||

| I think I work clean and orderly. | ||||

| I think I am polite and friendly. | ||||

| I think I comply with the health rules. | ||||

| I think I am sincere, sincere and helpful. | ||||

| I think I am patient. | ||||

| I think I have understanding and tolerance. | ||||

| I think I am determined and persistent. | ||||

| I think I am energetic and cute. | ||||

| I think I can make decisions about my job on my own. | ||||

| I think I have a sense of responsibility. | ||||

| I think my social relationships are positive. | ||||

| Organizational Commitment Scale | Question 1–9 | I am ready to make efforts beyond what is expected of me to contribute to the success of the institution I work for. | ||

| I speak very positively about my institution, telling my friends that the institution I currently work for is a very good institution to work in. | ||||

| I accept any assignment to continue working in this institution. | ||||

| I think my personal values and my organization’s values are very similar. | ||||

| I am proud to tell other people that I am a part of the organization I work for. | ||||

| This organization brings out my most positive aspects in terms of job performance. | ||||

| I am very glad that I work in this institution instead of other institutions. | ||||

| I really care about the future and success of the institution I work for. | ||||

| I think the institution I am currently working in is the best among the institutions I could work for. | ||||

| Motivation Scale | Intrinsic Motivation | Question 1–9 | I am successful in what I do. | |

| I have responsibility for the work I do. | ||||

| My colleagues appreciate me for my work. | ||||

| I believe that the work I do is worth doing. | ||||

| I believe that I have the authority to do my job fully. | ||||

| I believe the work I do is respectable. | ||||

| I see myself as an important part of my workplace. | ||||

| I have the right to decide on an issue related to my work. | ||||

| My managers always appreciate me for my work. | ||||

| Extrinsic Motivation | Question 10–24 | The management welcomes the leave request and does not reject it. | ||

| Physical conditions are suitable in my working environment. | ||||

| Food and beverages such as meals, tea, and coffee are served at the workplace. | ||||

| The tools and equipment in the workplace are sufficient. | ||||

| My relations with the employees are at a good level. | ||||

| Training activities such as meetings, seminars, and conferences are carried out by people who are experts in their fields. | ||||

| I believe that the workplace I work in will be better than its current situation in the future. | ||||

| My relations with my managers are good. | ||||

| I have the opportunity for promotion at my job. | ||||

| My managers help resolve conflicts with co-workers or customers. | ||||

| I get paid extra for my success. | ||||

| I am rewarded for my success. | ||||

| Colleagues are always there for me in solving personal and family problems. | ||||

| I believe I will retire from this workplace. | ||||

| I think the salary I receive from my work is sufficient. | ||||

References

- Muñoz-Comet, J.; Arcarons, A.F. The occupational attainment and job security of immigrant children in Spain. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022, 48, 2396–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Khan, U.; Lee, S.; Salik, M. The influence of management innovation and technological innovation on organization performance: A mediating role of sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvi, Ü.Y.; Sümer, N. The effects of job insecurity: A review on fundamental approaches and moderators of negative effects. J. Hum. Work. 2018, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hourie, E.; Malul, M.; Bar-El, R. The value of job security: Does having it matter? Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 139, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyraz, K.; Kama, B. Analyzing the effects of job security on job satisfaction organizational loyalty and intention to leave. Süleyman Demirel Univ. Econ. Adm. Sci. Dep. 2008, 3, 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Miraglia, M.; Alessandri, G.; Borgogni, L. Trajectory classes of job performance. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermerhorn, J.R.; Hunt, J.G.; Osborn, N.R. Managing Organizational Behavior; Mcgraw-Hill Book Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç Aksoy, Ş. Factors Affecting Employees’ Motivation: An Analysis in Mehmet Akif Ersoy University. Akdeniz Univ. Soc. Sci. Inst. J. 2020, 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K.; Li, N. The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiling, D. Trust and performance management in non-profit organizations. Innov. J. Public Sect. Innov. J. 2007, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.K.; Johnson, A.; Collıns, C.; Nguyen, H. Making the most of structural support: Moderating influence of employees’ clarity and negative affect. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 867–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulewicz-Sas, A.; Kinowska, H.; Fryczyńska, M. How sustainable human resource management affects work engagement and perceived employability. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 15, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchuk, H.; Štofková, J.; Krol, V.; Joshi, O.; Vasa, L. Social capital factors fostering the sustainable competitiveness of enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derin, N.; Ilkım, N.Ş. Investigation of job insecurity perception according to the demographic characteristics in textile sector. AKU J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2017, 19, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dınğın, Ö. Job Security in Human Resources Management and a Work Related to the Subject. J. Thrace University. 2008. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/dpusbe (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Probst, T.M. Development and validation of the job security index and the job security satisfaction scale: A classical test theory and IRT approach. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H. Job insecurity: Review of the international literature on definitions, prevalence, antecedents and consequences. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2005, 31, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, L.; Rosenblatt, Z. Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dığın, Ö.; Ünsar, S. The Determinants of Employees’ Job Security Perception and the Effect of the Pleasure of Job Security on Organizational Commitment, Job Stress and Turnover Intention. 2010. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/dpusbe (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Sadykova, G. The relationship between job insecurity and workplace procrastination. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Bus. 2016, 12, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emberland, J.S.; Rundmo, T. Implications of job insecurity perceptions and job insecurity responses for psychological well-being, turnover intentions and reported risk behavior. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, J.; Sverke, M.; Isaksson, K. A two-dimensional approach to job insecurity: Consequences for employee attitudes and well-being. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzgun, İ.K. The job security in Turkey and the effects to the labor market. Hacet. Univ. J. Dep. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2005, 6, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Loseby, P. Employment Security, Balancing and Economic Consideration; Quarum Books: Leicestershire, UK, 1992; ISBN 978-0899306926/0899306926. Available online: http://34.251.3.23:2082/record=b1351517~S11 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Lim, V.K. Job insecurity and its outcomes: Moderating effects of work-based and nonwork-based social support. Hum. Relat. 1996, 49, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, Ç.; Wasti, A. Job Security Index and Job Security Satisfaction Scale: Reliability and Validity Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 2, 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Aktuğ, S.S. Job Security in the Context of Social, Economic, Legal Basis and Assessment of Turkey. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Dokuz Eylül University, Social Sciences Institute, İzmir, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Çıtır I, Ö.; Kavi, E. Research about the relationship between perceived organizational trust and job security. J. Adm. Sci. 2010, 8, 243. [Google Scholar]

- Yiğit, Y. Condition to work at least six months in the application of job security from the view of Turkish Labor Law. Selçuk Univ. Law Dep. 2012, 20, 195–241. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, E.K.; Kacır, H. Review of the on-the-job training programs with regards to job precarity. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 1, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, S.; Bayram, N. Effect of job insecurity perception on employees: A case study. ISGUC J. Ind. Relat. Hum. Resour. 2013, 15, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Altay, S.; Epik, M.T. Perceptions of job insecurity and effect on business attitudes of 50 d research assistants: Research assistants at the faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences of Suleyman Demirel University. J. Univ. Ataturk Econ. Adm. Sci. 2016, 30, 1273–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Seçkin, Ş.N. The role of organizational support on perceived job insecurity, insider status and organizational cynicism relationship: A research on manufacturing sector. J. Yasar Univ. 2018, 13, 112–124. [Google Scholar]

- Dede, E. Effects of the Perceptions of Job Insecurity and Organizational Trust Level on the Organizational Citizenship Behaviours: A Research on the Public and Private Middle School Teachers. Unpublished Business Doctoral Thesis, İstanbul Ticaret University, Social Sciences Institute, Department of Business, Fatih, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Semerci, A.B. Job insecurity perceptions of employees: The differences between employees with and without parenting responsibilities. Sosyoekonomi 2018, 26, 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, D. Trends in international business thought and literature: Job insecurity: Emerging social roles of the 90s. Int. Exec. 1995, 37, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S.; Savcı, G.; Kapu, H. The effect of motivational factors on job performance and turnover intention. Adm. Econ. 2014, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Karakılıç, N.Y.; Candan, S. The investigation of the relationship between job security and employee performance with the structural equality model. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2019, 12, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Akı, E.; Tunç, D. Performance Appraisal System and Termination of Employment Contract Due to Insufficient Performance. 2010, pp. 79–96. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/ (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Akyüz, B.; Eşitti, B. The effects of organizational commitment on job performance and intention to leave in service organizations: A sample in Çanakkale Province. Bartın Univ. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2015, 6, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.P. Modeling the performance prediction problem in Industrial and organizational psychology. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Consulting Psychologists Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 687–732. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, S.K. The Linkage of Job Performance to Goal Setting, Work Motivation, Team Building, and Organizational Commitment in the High-Tech Industry in Taiwan. Ph.D. Thesis, H. Wayne Huizenga School of Business and Entrepreneurship Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Erol, E. The Role of Recreational Activity in the Effect of the Burnout Level on the Job Performance: A Case Study Over Food and Beverage Establishments. Ph.D. Thesis, Hacı Bayram Veli University, Postgraduate Education Institute, Ankara, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Unlu, O.; Yurur, S. Emotional Labor, Emotional Exhaustion and Task/Contextual Performance Relationship: A Study with Service Sector Workers in Yalova. Erciyes Univ. J. Fac. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2011, 37, 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bağcı, Z. The effect of job satisfaction of employee on task and contextual performance. J. Manag. Econ. Res. 2014, 24, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, A.; Arar, T.; Öneren, M.; Kartal, C. The effect of ethical tendencies on the relationship between psychobiological personality theory factors and job performance. J. Bus. Res. Turk. 2019, 11, 2272–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polatçı, S.; Özçalık, F. The mediating role of positive and negative affectivity on the relationship between perceived organizational justice and counterproductive work behavior. Dokuz Eylul Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Inst. 2015, 17, 215–234. [Google Scholar]

- San, İ. Organizational Commitment and Its Effects on Working Life; Field Study. Unpublished Graduate Thesis, İstanbul Ticaret University, Fatih, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Swailes, S. Organizational commitment: A critique of the construct and measures. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2002, 4, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B. Building organizational commitment: The socialization of managers in work organizations author. Adm. Sci. Q. 1974, 19, 533–546. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, H.S. Notes on the concept of commitment. Am. J. Sociol. 1960, 66, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Gellatly, I.R. Affective and continuance commitment to the organization: Evaluation of measures and analysis of concurrent and time-lagged relations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 75, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Boulian, P.V. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- İnce, M.; Gül, H. Yönetimde yeni bir paradigma Örgütsel bağlılık [Trans. A New Paradigm in Management Organizational Commitment]; Cizgi Publishing House: Konya, Turkey, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Şenol, F. The Effect of Job Security on the Perception of Motivation Tools: A Study in Hotel Enterprises. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Afyon Kocatepe University, Social Sciences Institute, Afyonkarahisar, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ulukuş, K.S. Motivation theories and the elements of the leading management effect on the motivation of the individual. J. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Abadiyah, R.; Eliyana, A.; Sridadi, A.R. Motivation, leadership, supply chain management toward employee green behavior with organizational culture as a mediating variable. Int. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2020, 9, 981–989. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, S. Public service motivation theory: A literature review. Int. J. Econ. Soc. Res. 2015, 11, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sabuncuoğlu, Z.; Tüz, M. Organizational Psychology, Reviewed; Furkan Offset: Bursa, Turkey, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.; Jianke, L.; Kayhan, T.; Khaskheli, M.B. Digital Technology Application and Enterprise Competitiveness: The Mediating Role of ESG Performance and Green Technology Innovation. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Ao, L.; Bansal, R.; Pruthi, R.; Khaskheli, M.B. Impact of Social Media Influencers on Customer Engagement and Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, M. The impact of occupational health and safety practices on organizational commitment: A field study. Int. J. Soc. Res. 2020, 15, 2132–2163. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, İ.; Büyükbeşe, T. The relationship between job security and general work behaviors of employees. Erciyes Univ. J. Fac. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2004, 23, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Altaş, S.S.; Çekmecelioğlu, H.G. The impact of distributive and procedural justice on Pre-school-teachers organizational commitment, job satisfaction and job performance. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2015, 29, 421–439. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank. 4th Quarter Report; Central Bank 3 Press Report; Central Bank: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, T.M. Antecedents and Consequences of Job Insecurity: An Integrated Model. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois, Champaign, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Motowidlo, S.J.; Van Scotter, J.R. Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaz, C.J. The relative importance of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards as determinants of work satisfaction. Sociol. Q. 1985, 26, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 366 | 62.9 |

| Male | 216 | 37.1 | |

| Age | 20–24 | 20 | 3.4 |

| 25–30 | 71 | 12.2 | |

| 31–34 | 139 | 23.9 | |

| 35–39 | 146 | 25.1 | |

| 40–44 | 126 | 21.6 | |

| 45 and above | 80 | 13.7 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 430 | 73.9 |

| Single | 152 | 26.1 | |

| Educational Status | Primary School | 28 | 4.8 |

| High School | 200 | 34.4 | |

| University Graduate | 34 | 5.8 | |

| Master’s | 240 | 41.2 | |

| Doctorate | 80 | 13.7 | |

| Which title do you have? | Employee | 321 | 55.2 |

| Low-Level Management | 156 | 26.8 | |

| Mid-Level Management | 91 | 15.6 | |

| High-Level Management | 14 | 2.4 | |

| How many years have you been working at your workplace? | 1–4 years | 111 | 19.1 |

| 5–9 years | 178 | 30.6 | |

| 10–14 years | 172 | 29.6 | |

| 15–19 years | 76 | 13.1 | |

| 20–25 years | 19 | 3.3 | |

| 25 years or more | 26 | 4.5 | |

| What is the total time of your service in the profession? | 1–4 years | 67 | 11.5 |

| 5–9 years | 136 | 23.4 | |

| 10–14 years | 180 | 30.9 | |

| 15–19 years | 113 | 19.4 | |

| 20–25 years | 52 | 8.9 | |

| 25 years or more | 34 | 5.8 | |

| Sectoral structure of your workplace | Public or Public Administration | 232 | 39.9 |

| >Private Sector | 350 | 60.1 | |

| Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Job Security | ||

| Job Security Index | 6 | 0.85 |

| Job Security Satisfaction | 6 | 0.87 |

| Total | 12 | 0.92 |

| Job Performance Scale | ||

| Functional Performance | 4 | 0.82 |

| Contextual Performance | 20 | 0.94 |

| Total | 24 | 0.95 |

| Organizational Commitment Scale | ||

| Total | 9 | 0.93 |

| Job Motivation Scale | ||

| Intrinsic Motivation | 9 | 0.93 |

| Extrinsic Motivation | 15 | 0.89 |

| Total | 24 | 0.93 |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | Approx. Chi-Square | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | Sig | |||

| Per. Job Sec. | 0.917 | 3532.399 | 55 | 0.000 |

| Sus. Job Perf. | 0.893 | 8171.102 | 210 | 0.000 |

| Organizational Com. | 0.923 | 4194.404 | 36 | 0.000 |

| Motivation | 0.887 | 6754.461 | 210 | 0.000 |

| Group | n | Rank Av. | Z | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Security Index | Public or public admin. | 232 | 25.08 | 404.35 | 13.209 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 19.68 | 216.70 | |||

| n | ss | t | p | |||

| Job Security Satisfaction | Public or public admin. | 232 | 25.06 | 3.90 | 18.394 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 18.59 | 4.32 | |||

| Job Security | Public or public admin. | 232 | 50.13 | 7.72 | 17.938 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 38.27 | 7.87 | |||

| Group | n | ss | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task Performance | Public or public admin. | 232 | 18.30 | 2.08 | 4.504 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 17.52 | 2.00 | |||

| Group | n | Rank Av. | Z | p | ||

| Contextual Performance | Public or public admin. | 232 | 92.96 | 355.66 | 7.533 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 88.32 | 248.97 | |||

| Job Performance | Public or public admin. | 232 | 111.26 | 355.29 | 7.478 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 105.84 | 249.22 |

| Group | n | Rank Av. | Z | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task performance | Public or public admin. | 232 | 40.47 | 409.08 | 13.781 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 32.43 | 213.56 |

| Group | n | ss | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic motivation | Public or public admin. | 232 | 40.73 | 4.93 | 6.100 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 38.29 | 4.59 | |||

| Extrinsic motivation | Public or public admin. | 232 | 61.30 | 8.81 | 10.027 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 54.27 | 7.71 | |||

| Motivation | Public or public admin. | 232 | 102.03 | 12.94 | 9.143 * | 0.000 |

| Private sector | 350 | 92.56 | 11.09 |

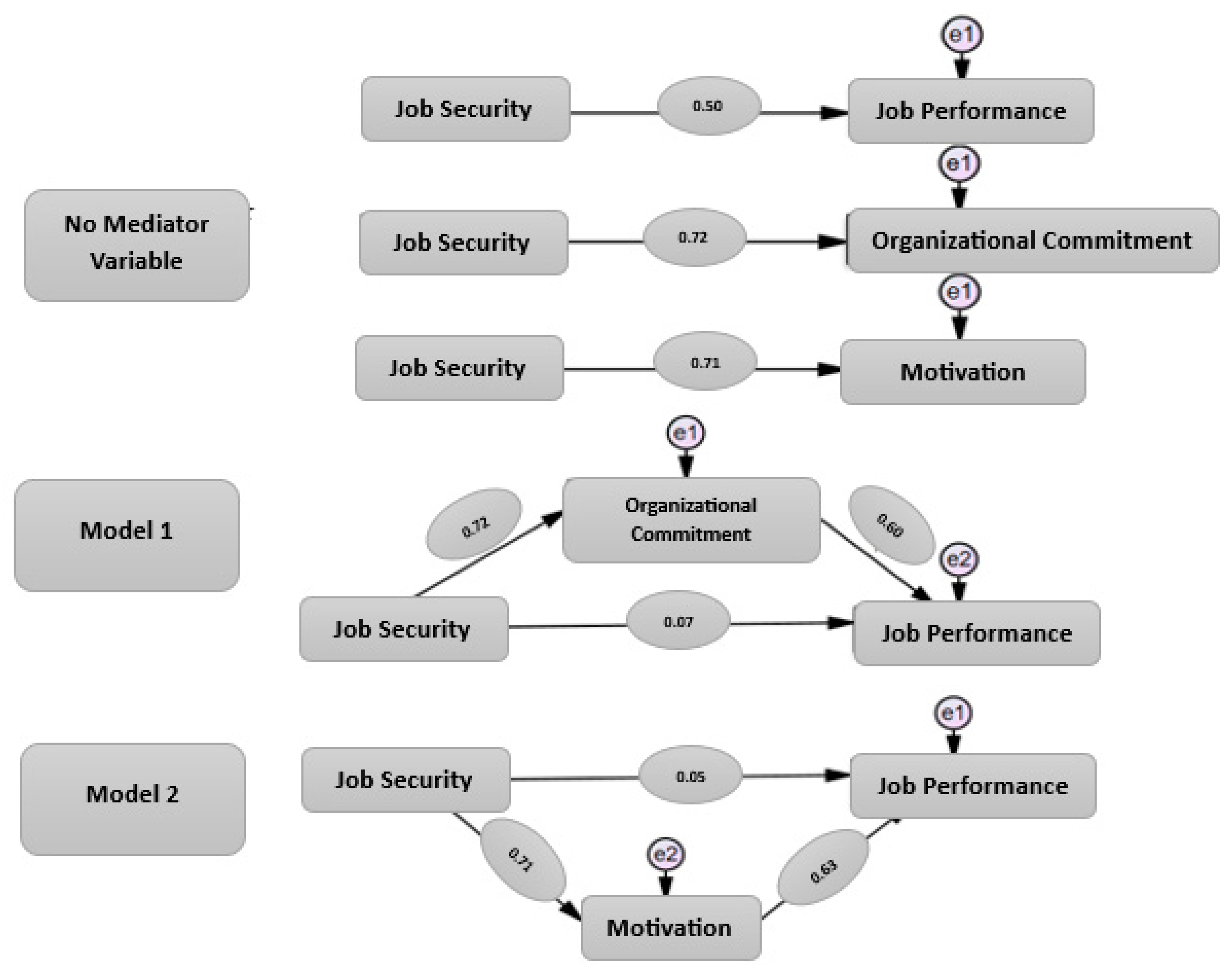

| Paths | Path Coefficient (Β) | Std. Path Coefficient (β) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No mediating variables | Job security → job performance | 0.524 | 0.502 | <0.05 |

| Job security → organizational commitment | 0.525 | 0.720 | <0.05 | |

| Job security → motivation | 0.924 | 0.707 | <0.05 | |

| Model 1 | Job Security → organizational commitment (direct impact) | 0.525 | 0.720 | <0.05 |

| Organizational commitment → job performance (direct effect) | 0.863 | 0.602 | <0.05 | |

| Job security → job performance (direct effect) | 0.072 | 0.069 | 0.129 | |

| Job security → org.com.→ job performance (indirect effect) | 0.453 | 0.433 | ||

| Model 2 | Job security → motivation (direct effect) | 0.924 | 0.707 | <0.05 |

| Motivation → job performance (direct effect) | 0.506 | 0.632 | <0.05 | |

| Job security → job performance (direct effect) | 0.057 | 0.055 | 0.208 | |

| Job security → motivation → job performance (indirect effect) | 0.467 | 0.447 |

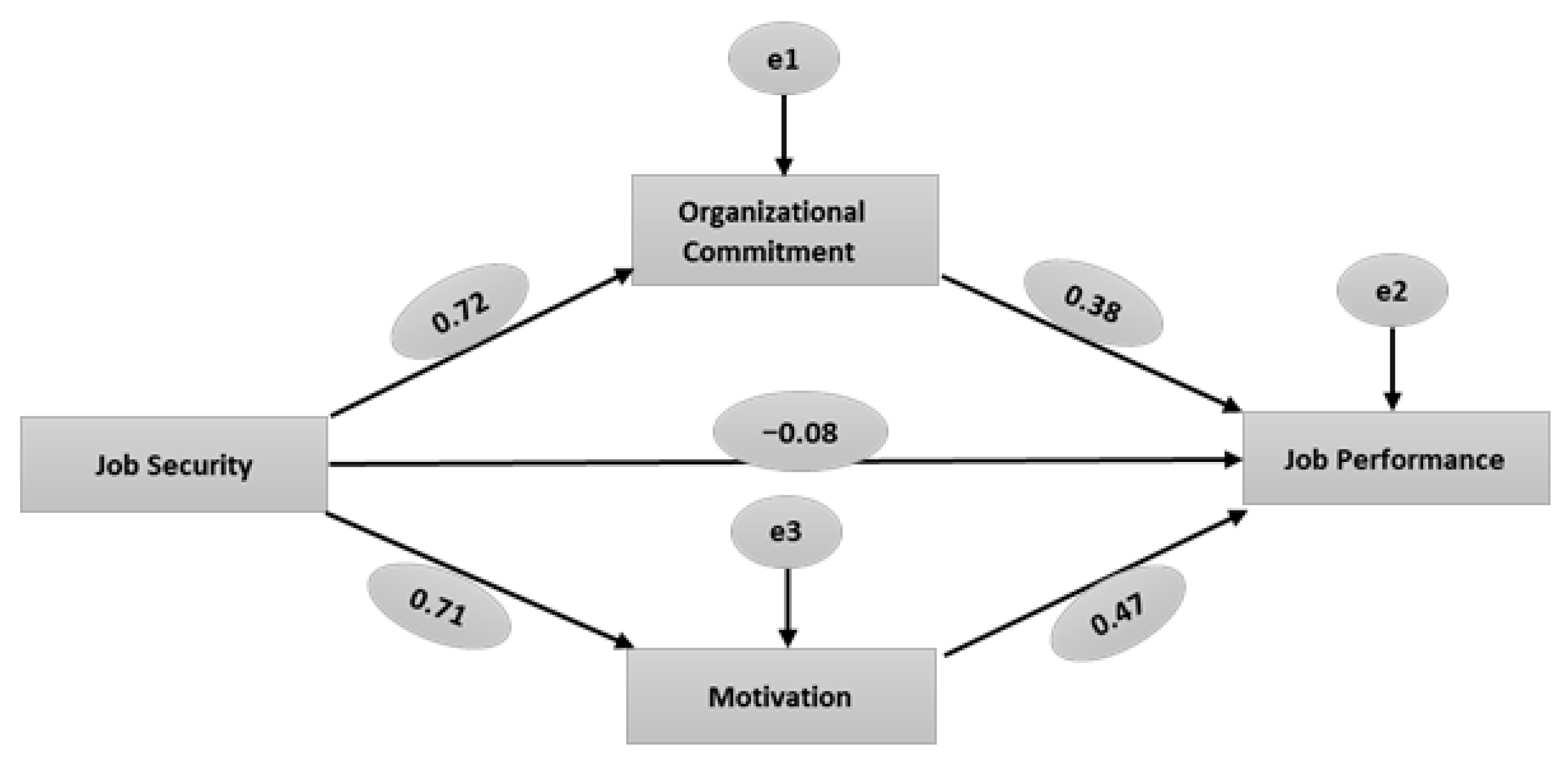

| Path Coefficient (Β) | Std. Error (Sβ) | Std. Path Coefficient (β) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Org. com. ← Job security | 0.525 | 0.021 | 0.720 | <0.05 |

| Motivation ← Job security | 0.924 | 0.038 | 0.707 | <0.05 |

| Job performance ← Job security | −0.079 | 0.054 | −0.079 | 0.141 |

| Job performance ← Org. com. | 0.523 | 0.061 | 0.381 | <0.05 |

| Job performance ← Motivation | 0.356 | 0.033 | 0.465 | <0.05 |

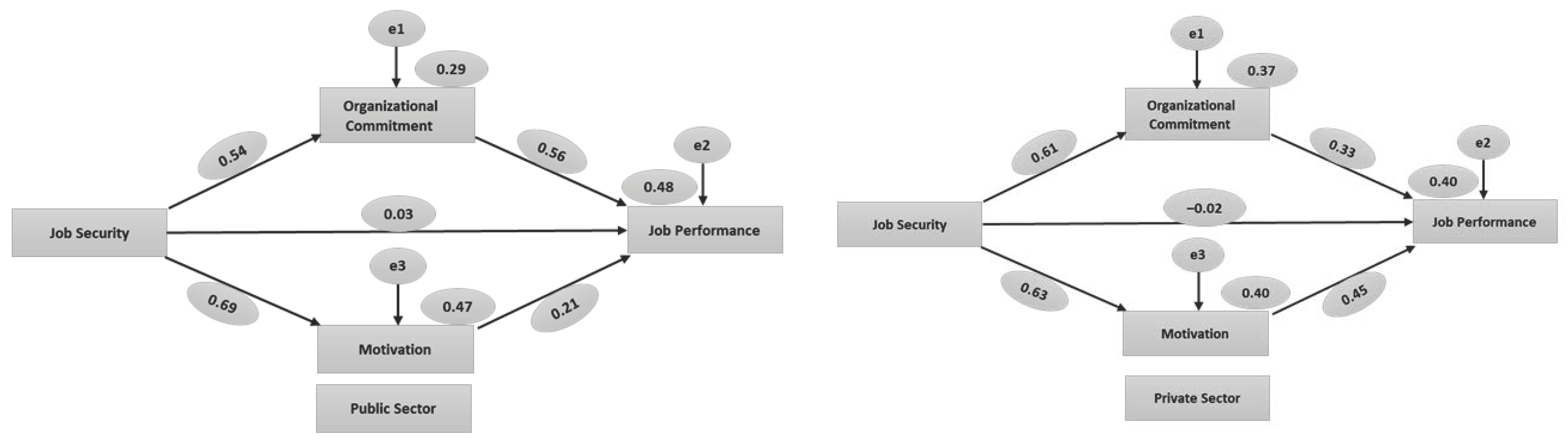

| Public | Private | Group Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std. Path Coefficient (β) | p | Std. Path Coefficient (β) | p | ||

| Org. com. ← job security | 0.538 | <0.05 | 0.612 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Motivation ← job security | 0.688 | <0.05 | 0.634 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Job performance ← org. com. | 0.561 | <0.05 | 0.327 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Job performance ← motivation | 0.208 | <0.05 | 0.452 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Job performance ← job security | 0.034 | 0.642 | −0.024 | 0.699 | 0.504 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kayar, S.; Yeşilada, T. Quartet of Sustainable Job Security, Job Performance, Organizational Commitment, and Motivation in an Emerging Economy: Focusing on Northern Cyprus. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166764

Kayar S, Yeşilada T. Quartet of Sustainable Job Security, Job Performance, Organizational Commitment, and Motivation in an Emerging Economy: Focusing on Northern Cyprus. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):6764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166764

Chicago/Turabian StyleKayar, Serhan, and Tahir Yeşilada. 2024. "Quartet of Sustainable Job Security, Job Performance, Organizational Commitment, and Motivation in an Emerging Economy: Focusing on Northern Cyprus" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 6764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166764

APA StyleKayar, S., & Yeşilada, T. (2024). Quartet of Sustainable Job Security, Job Performance, Organizational Commitment, and Motivation in an Emerging Economy: Focusing on Northern Cyprus. Sustainability, 16(16), 6764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166764