Rethinking External Environmental Analysis for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Beverage Manufacturing Industry in a Southern African Country

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. External Environmental Analysis

2.2. PESTE Forces of Change

2.2.1. Political–Legal Drivers of Change

2.2.2. Economic Drivers of Change

2.2.3. Socio-Cultural Drivers of Change

2.2.4. Technological Drivers of Change

2.2.5. Ecological (Natural Environmental) Drivers of Change

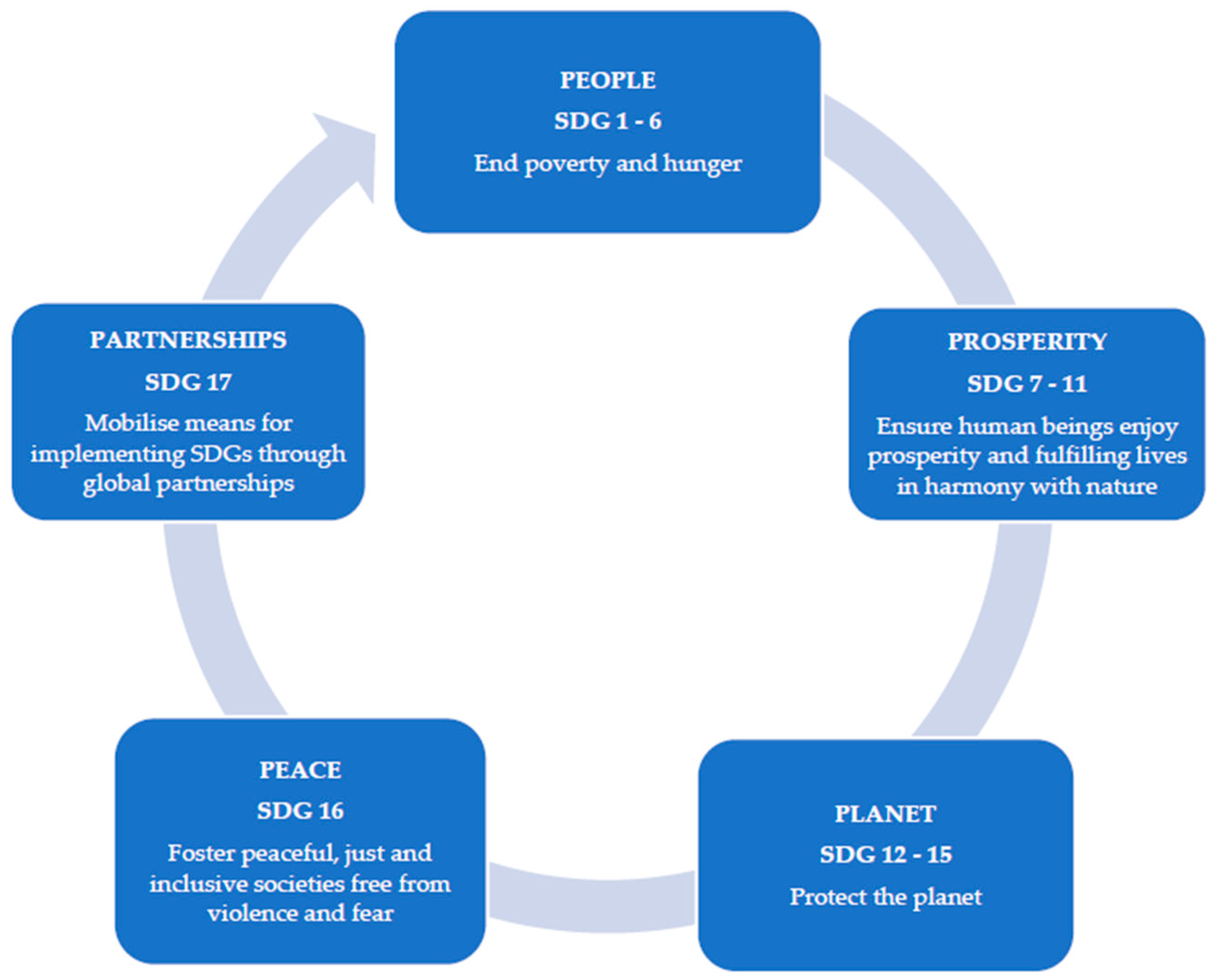

2.3. Sustainable Development as Megaforce for Change

2.4. The Relationship between PESTE Forces and Sustainable Development Goals

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Strategy

3.2. Population and Sampling

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Quality Assurance/Trustworthiness of the Study

3.6. Ethical Considerations

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- the importance of sustainable development,

- conceptualising sustainable development, and

- current practices on sustainable development in beverage manufacturing companies.

4.1. The Importance of Sustainable Development

Thanks, so much for considering me to participate in the PhD research. I feel quite humbled to have been considered for this. The topic is centred on sustainable development goals and leadership. I must admit that I am not well versed on the first part, that of sustainable development particularly as it relates to SDGs. It would be unfair to you to even attempt to respond as I feel that this is an area I still need to understand more. In fact, as I went through the questions, I noted how far I lacked information on this topic. I would have loved to participate towards your research topic. Regrettably due to the foregoing, I am unable to assist in this instance.

I know SDGs developed from millennium development goals [MDGs]. I think at that point, which is some years back, it was just academic. We thought these are NGO [non-governmental organisations] and UN issues. But I know for a fact [that] over the last year or two we have focused on SDGs, which we think, at least, are relevant to our industry.

We are fully aware that, although SDGs are UN-sponsored and government-driven, they have an impact at industry level. Corporates have a duty to contribute to poverty eradication, gender sensitivity, renewable energy, energy efficiencies, refrigeration that protects the ozone layer, environmental sustainability, compliance with ISO 14001, buying and designing equipment that contributes to sustainability, and managing profits to include designing processes that consider sustainable development.

We need a plan that engages the UN and the government. Then we need a plan of sharing resources as we set up milestones and sharing the SDGs across the industry so that we cover as much ground as possible. One point that stuck in my mind was that there is no ownership. The government thinks it’s the UN. The UN thinks it’s the government. Then the industry thinks we would want to contribute for sustainable profit.

4.2. Conceptualising Sustainable Development

The understanding we have in our organisation of sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It is also about promoting people, planet, and profit.

My understanding of sustainable development is that, in the process of making livelihoods, where livelihood is when people apply all the means to make a living to [by] either using their competencies and [or] available resources for them to be able to live. In the process of making livelihoods, they should make sure that the natural environment or the ecosystem is preserved, such that the next generation don’t get it worse than we found it or enhance it.

Here, we are saying the world is not just for today, but the world must be there tomorrow, and a better world must be there tomorrow for future generations. For us what legacy are we leaving? So, we are looking at a better world ever improving towards better social welfare, better environmental impacts, better economic welfare, and inclusivity.

We have a responsibility as current citizens of the world to ensure that as we do our day-to-day activities, be it in business, farming or in our communities, we are also mindful of the fact that, there will be future citizens. Therefore, whatever we do today must ensure that we guarantee a future for the next generation. From a business perspective, profit must be obtained responsibly in a sustainable manner.

As we do our business, there should be a sense of responsibility and to do so with minimum harm to the environment so that we safeguard the environment for future generations.

My understanding goes back to the decision by the United Nations to identify the 17 SDGs, as they call them, which ought to be a template to guide leaders whether they are in the public or private sector as they go about the business of running their organisations. Essentially, sustainable development is about looking into the future so that we have a better world in every respect and in a lot of diverse areas.

Sustainable development is a complex term. Very few people understand it so well. It is a scenario that has been evolving over the years. When you think you understand it, then someone comes up with something new to make it a little more complex.

4.3. Current Practices on Sustainable Development in Beverage Manufacturing Companies

We are very much at the beginning of the cycle, if I may say so. We don’t consider ourselves as advanced. But at least we are aware of what SDGs are and we are conscious of the need for measuring ourselves against those SDGs.

My organization is a member of the Business Council for Sustainable Development (BCSD) and a franchised bottler.

My organization has embraced SDGs by selecting what is applicable to its own circumstance, such as gender equality, health and well-being of employees, water usage, sustainable manufacturing, and climate change.

We have a full-time sustainability manager responsible for overseeing our sustainability initiatives across our business.

If you look at our strategic plan, we have said we want to be a forceful good in the communities and environments that we operate. We have set ourselves on a journey that recognises that our activities have a negative impact in many cases of [on] the environment. Therefore, we must take mitigating measures to ensure that as we do our business we do so in a sustainable manner.

Sustainability has become a core element of the business strategy. It is now entrenched in [the] companies’ strategic decisions; it is discussed at companies’ board level; it is now an agenda at board meetings, and companies are even hiring or making investments in decisions in sustainable development.

Management must understand that the resource they are using is finite and it must be used in a manner at best to replenish that resource. Whilst, at the same time, managing the waste created by such a process.

Sustainable development is now an imperative for business and can no longer be ignored; it is the reason why people work every day, with green jobs being the sustainable way of creating jobs, making a difference in people’s lives, taking people out of poverty because poverty is dehumanizing, prevents social exclusion; consideration of ecological risks, and a nexus between the environment and economic development.

In our industry, sustainable development is a social license to operate that has led us to look at SDGs. We have also expanded these to look beyond the factory and the customers we do business with to go into the wider community. That is where our sustainable elements then come in, our social license to operate.

The organization is part of the community and what a favour to be running this organisation in the community! So, serve the community and serve the world in which you are operating, where the [our] children will be operating tomorrow.

5. Implications, Recommendations, and Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications for Business

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Limitations of Study

5.4. Directions for Future Research

5.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cengiz, H. External Environment Analysis. In Strategic Management; Ulukan, C., Ed.; Anadolu University: Eskişehir, Turkey, 2020; pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Çitilci, T.; Akbalık, M. The Importance of PESTEL Analysis for Environmental Scanning Process. In Handbook of Research on Decision-Making Techniques in Financial Marketing; Dinçer, H., Yüksel, S., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 336–357. [Google Scholar]

- Santoso, R.; Permana, E. Analysis of the Business Environment in Construction Service Industry in DKI Jakarta, Indonesia. Maj. Ilm. Bijak 2021, 18, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Amuna, Y.M.; Al Shobaki, M.J.; Abu Naser, S.S. Strategic Environmental Scanning: An Approach for Crises Management. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Electr. Eng. 2017, 6, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sammut-Bonnici, T.; Galea, D. PEST analysis. Wiley Encycl. Manag. 2015, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiku, K.M. External Factors and Their Impact on Enterprise Strategic Management—A Literature Review. Eur. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 6, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A. Impact of External Business Environment an Organisational Performance of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Osun State, Nigeria. Sch. Int. J. Bus. Policy 2016, 3, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Shatilo, O. The Impact of External and Internal Factors on Strategic Management of Innovation Processes at Company Level. Ekonomika 2019, 98, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturup, S.; Low, N. Sustainable development and mega infrastructure: An overview of the issues. J. Mega Infrastruct. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 1, 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu, A.M. Sustainable Development, a Multidimensional Concept. Inf. Soc. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 82–86. Available online: https://www.utgjiu.ro/revista/ec/pdf/2015-03%20Special/14_Teodorescu%20A1.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Borowski, P.F.; Patuk, I. Environmental, social and economic factors in sustainable development with food, energy and eco-space aspect security. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Assembly. Outcome document of the United Nations summit for the adoption of the post-2015 development agenda. In Sixty-Ninth Session Agenda13(a) &115; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shtal, T.V.; Buriak, M.M.; Amirbekuly, Y.; Ukubassova, G.S.; Kaskin, T.T.; Toiboldinova, Z.G. Methods of analysis of the external environment of business activities. Revista 2018, 39, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kinange, U.; Patil, N. A Conceptual Paper on External Environment Analysis Models. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Marketing MARKCON 2020, Karnataka, India, 9–11 January 2020; Indus Business Academy: Bangalore, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, S. The Methods of External Environmental Analysis in Health Institutions. Dan. Sci. J. 2023, 71, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Gurel, E. SWOT Analysis: A Theoretical Review. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2017, 10, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghicajanu, M. Analysis of factors from the external environment in changing business processes. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 290, 07008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, F.J. Scanning the Business Environment; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 14th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, R. The PESTLE Analysis; Nerdynaut: Avissawella, Sri Lanka, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Athishec, G. International Business Environment: Challenges and Changes. Res. J. Manag. Sci. 2013, 2, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- DESA. Global Governance and Global Rules for Development in the Post-2015 Era; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/cdp/cdp_publications/2014cdppolicynote.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Hwang, K.D. The Historical Evolution of SADC(C) and Regionalism in Southern Africa. Int. Area Stud. Rev. 2007, 10, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. Global Prospects and Policies. In World Economic Outlook: Steady but Slow: Resilience Amid Divergence; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shurkin, M.; Noyes, A.; Adgie, M.K. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Opportunity to Rethink Strategic Competition on the Continent; Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PEA1000/PEA1055-1/RAND_PEA1055-1.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Lutz, C.; Meyer, B. Economic impacts of higher oil and gas prices: The role of international trade for Germany. Energy Econ. 2009, 31, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, R. Africa: A Political Economy of Continued Crisis. Afr. Focus 2018, 31, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. Global Prospects and Policies. In World Economic Outlook: Subdued Demand—Symptoms and Remedies; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mazorodze, B.T.; Tewari, D.D. Real exchange rate undervaluation and sectoral growth in South Africa. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2018, 9, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teachout, M.; Zipfel, C. The Economic Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns in Sub-Saharan Africa; International Growth Centre: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2020/05/Teachout-and-Zipfel-2020-policy-brief-.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Siemieniuch, C.E.; Sinclair, M.A.; Henshaw, M.J. Global drivers, sustainable manufacturing and systems ergonomics. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 51, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosthuizen, M.; Schutte, J. SADC Futures of Green Infrastructure: Visionary Scenarios and Transformative Pathways to Regeneration; South African Institute of International Affairs: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2023; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2015 (ST/ESA/SER.A/390); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Graf, M.; Ghez, J.; Khodyakov, D.; Yakub, O. Indvidual Empowerment: Global Societal Trends to 2030; Rand Corporation: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sahay, A. Reverse Brain Drain: New Strategies by Developed and Developing Countries. In Global Diasporas and Development; Sahoo, S., Pattanaik, B.K., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ayittey, F.K.; Ayittey, M.K.; Chiwero, N.B.; Kamasah, J.S.; Dzuvor, C. Economic impacts of Wuhan 2019-nCoV on China and the world. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauda, A.; Ismaila, M. Influence of Technological Environmental Factors on Strategic Choice of Quoted Manufacturing Firms in Nigeria’s Food and Beverage Industry. Int. J. Bus. Humanit. Technol. 2013, 3, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Like it or not, here I am Social media and the workplace. In A Middle East Point of View; Deloitte: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2015; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sassenberg, K. It Is About the Web and the User: The Effects of Web Use Depend on Person Characteristics. Psychol. Inq. 2013, 24, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanta, A.B.; Mutsonziwa, K.; Goosen, R.; Emanuel, M.; Kettles, N. The Role of Mobile Money in Financial Inclusion in the SADC Region: Evidence Using FinScope Surveys; FinMark: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016; Available online: https://finmark.org.za/system/documents/files/000/000/258/original/mobile-money-and-financial-inclusion-in-sadc-1.pdf?1602600110 (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Zeufack, A.G.; Calderon, C.; Kambou, G.; Kubota, M.; Korman, V.; Canales, C.C.; Aviomoh, H.E. COVID-19 and the Future of Work in Africa: Emerging Trends in Digital Technology Adoption. Afr. Pulse 2021, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, V. FinTechs in Sub-Saharan Africa an Overview of Market Developments and Investment Opportunities; EY: Birmingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, W. Ethics and Sustainable Development. In Quest for Sustainable Development; Juta and Company: Cape Town, South Africa, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barson, M. Land Management Practice Trends in South Australia’s Horticulture Industry: Caring for Our Country. Sustain. Pract. Fact Sheet 2013, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gadallah, M.A.; Sayed, Z. Impact of Different Water Pollution Sources on Antioxident Defense Ability in Three Acquatic Macrophytes in Assiut Province, Egypt. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 10, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. The IUCN Programme 2013–2016; IUCN: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/content/documents/the_business_journey_for_the_iucn_congress_2016.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Perrings, C.; Halkos, G. Agriculture and the Threat to Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 095015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, C.; Haig, G.H.; Timmermann, A.; Damste, J.S.; Sigman, B.D.; Can, M.A.; Verschuren, D. Reduced Interannual Rainfall Variability in East Africa During the Last Ice Age. Science 2011, 333, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, J.; Howard, A.C.; Mills, T.; Rickard, S.; Macey, S. A bumpy road: Maximising the value of a resource corridor. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2017, 4, 339–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbooi, K. Review of Land Reform in Southern Africa; PLAAS University of Western Cape: Cape Town, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Byamugisha, F.F. Agricultural Land Redistribution and Land Administration in Sub-Saharan Africa: Case Studies of Recent Reforms; Byamugisha, F.F., Ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Victor Ongoma, V.; Epule, T.E.; Brouziyne, Y.; Tanarhte, M.; Chehbouni, A. COVID-19 response in Africa: Impacts and lessons for environmental management and climate change adaptation. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 5537–5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikwambana, L.; Kganyago, M. Assessing the Responses of Aviation-Related SO2 and NO2 Emissions to COVID-19 Lockdown Regulations in South Africa. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. A Holistic Perspective on Corporate Sustainability Drivers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainullina, Y.R. Formation of Innovative Approaches to the Designing of a Three-Pronged Concept of Sustainable Development of Economic Systems in the Age of Globalisation. J. Internet Bank. Financ. 2016, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Halisçelik, E.; Soytas, M.A. Sustainable development from millennium 2015 to Sustainable Development Goals 2030. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 545–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H. Sustainable Development: The colors of sustainable leadership in learning organization. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S. Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 278–331. [Google Scholar]

- Kantabutra, S. Toward a System Theory of Corporate Sustainability: An Interim Struggle. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijkers, O. Intergenerational Equity and the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puaschunder, J.M. On the Social Representations of Intergenerational Equity. In Governance & Climate Justice: Global South & Developing Nations; Puaschunder, J.M., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan Cham: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stazyk, E.C.; Moldavanova, A.; Frederickson, H.G. Sustainability, Intergenerational Social Equity, and the Socially Responsible Organisation. Adm. Soc. 2016, 48, 655–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibert, C.J.; Thiele, L.; Peterson, A.; Monroe, M. The Ethics of Sustainability. 2012. Available online: http://rio20.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Ethics-of-Sustainability-Textbook.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate Sustainability Strategies: Sustainability Profiles and Maturity Levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Global Sustainable Development Report 2016; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2328Global%20Sustainable%20development%20report%202016%20(final).pdf (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- Wysokinska, Z. Millenium Development Goals/UN and Sustainable Development Goals/UN as Instruments for Realising Sustainable Development Concept in the Global Economy. Comp. Econ. Res. 2017, 20, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, S.; Hoy, G.; Berliner, T.; Aedy, T. Projecting Progress: Reaching the SDGs by 2030; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://odi.org/en/publications/projecting-progress-reaching-the-sdgs-by-2030/ (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Carat, J.B. Unhead Voices: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Milleninum Development Goals’ Evolution into SDGs. Third World Quartely 2017, 38, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.; Smith, C. Addressing the threats to tourism sustainability using systems thinking: A case study of Cat Ba Island, Vietnam. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1504–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terres, Z.; Baxter, G.; Rivera, A.; Nelson, J. Business and the United Nations. Working Together towards the Sustainable Development Goals: A Framework of Action. 2015. Available online: https://www.sdgfund.org/sites/default/files/business-and-un/SDGF_BFP_HKSCSRI_Business_and_SDGs-Web_Version.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Lee, K. A Phenomenological Exploration of the Student Experience of Online PHD Studies. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2020, 15, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naderifar, M.; Ghaljaie, F. Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 2017, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, C. Business Research Methods; Cengage Learnin: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Determining Sample Size. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentles, S.J.; Charles, C.; Ploeg, J.; McKibbon, K. Sampling in Qualitative Research: Insights from an Overview of the Methods Literature. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1772–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P. Focus Group Methodology: Principles and Practice; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Birchall, J. Qualitative Inquiry as a Method to Extract Personal Narratives: Approach to Research into Organizational Climate Change Mitigation. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.; Mash, B. African Primary Care Research: Qualitative interviewing in primary care. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2014, 6, a632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khankeh, H.; Ranjbar, M.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D.; Zargham-Boroujeni, A.; Johansson, E. Challenges in conducting qualitative research in health: A conceptual paper. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2015, 20, 635–641. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, J. Ensuring Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. Belitung Nurs. J. 2015, 1, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Assoc. Educ. Commun. Technol. 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for Ensuring Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research Projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 6th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelsma, J.; Clow, S. Ethical Issues Relating to Qualitative Research. SA J. Physiother. 2005, 61, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n15/291/89/pdf/n1529189.pdf?token=uxziuBxZJ5TBuYTha9&fe=true (accessed on 3 April 2024).

| Acronym | Categories | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | PEST | Political; Economic; Social; Technical |

| 2 | PESTE | Political; Economic; Social; Technological; Ecological |

| 3 | PESTLE | Political; Economic; Social; Technological; Legal; Ecological |

| 4 | PESTELE | Political; Economic; Social; Technological; Ethical; Legal; Ecological |

| 5 | PESTLID | Political; Economic; Social; Technological; Legal; International; Demographic |

| Facets | Nuances Indicating Importance of Understanding Sustainable Development |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | Lack of knowledge. Potential participant declines participation in interview. Focused on SDGs, which we think, at least, are relevant to our industry (P9) |

| Impact | They (SDGs) have an impact at industry level (P1); designing processes that consider sustainable development (P1) |

| Ownership | Sharing SDGs across industries (P9); huge opportunity for ownership of SDGs (P9) |

| Dimensions | Nuances Indicating Sustainable Development as an Environmental Force |

|---|---|

| Brundtland Commission definition | Sustainable development promotes people, planet, and profit (P3) |

| Livelihoods | Preservation of the ecosystem in the process of making livelihoods (P8) |

| Futuristic | Creates better social welfare, better environmental impacts, better economic welfare, and inclusivity (P12) |

| Responsible management | Profit must be obtained responsibly in a sustainable manner (P5); safeguard the environment for future generations (P10) |

| SDGs | Sustainable development is about looking into the future (P4) |

| Perspective | Nuances through Organisational Lens |

|---|---|

| Association | Member of the Business Council for Sustainable Development (BCSD) (P3) |

| Selective approach | Embraced SDGs by selecting what is applicable (P11) |

| Functional approach | Sustainability manager responsible for overseeing sustainability initiatives; doing business in a sustainable manner (P10) |

| Embedding sustainability in strategy | Sustainability has become a core element of the business strategy (P6); conscious of the need for measuring ourselves against the SDGs (P4) |

| Resource management | Managing waste (P7) |

| Imperative approach | Sustainable development is now an imperative for business (P6) |

| Social licensing | Sustainable in the community (P9); favour to be running this organisation in the community (P12) |

| 5-Ps | SDGs | PESTE Force |

|---|---|---|

| People | SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and well-being of employees and families SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empowerment of women | Social |

| SDG 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation | Social Economic | |

| Prosperity | SDG 8: Sustainable economic growth | Economic |

| SDG 9: Foster innovation | Economic Technological | |

| Planet | SDG 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns SDG 13: Combat climate change and its impacts SDG 15: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss | Ecological |

| Peace | SDG 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive workplace for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive systems at all work levels | Political |

| Partnerships | SDG 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and partnership with government and communities in sustainable development | Socio-political Technological |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruwanika, E.Q.F.; Massyn, L. Rethinking External Environmental Analysis for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Beverage Manufacturing Industry in a Southern African Country. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166759

Ruwanika EQF, Massyn L. Rethinking External Environmental Analysis for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Beverage Manufacturing Industry in a Southern African Country. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):6759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166759

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuwanika, Eliot Quinz Farai, and Liezel Massyn. 2024. "Rethinking External Environmental Analysis for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Beverage Manufacturing Industry in a Southern African Country" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 6759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166759

APA StyleRuwanika, E. Q. F., & Massyn, L. (2024). Rethinking External Environmental Analysis for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Beverage Manufacturing Industry in a Southern African Country. Sustainability, 16(16), 6759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166759