Sustainable Brand Resilience: Mitigating Panic Buying through Brand Value and Food Waste Attitudes Amid Social Media Misinformation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. User-Generated Content Leading to Inaccurate Information

2.2. Inaccurate Information and Panic Buying

2.3. Food Waste and Brand Values

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures and Measurement

3.3. Methods of Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

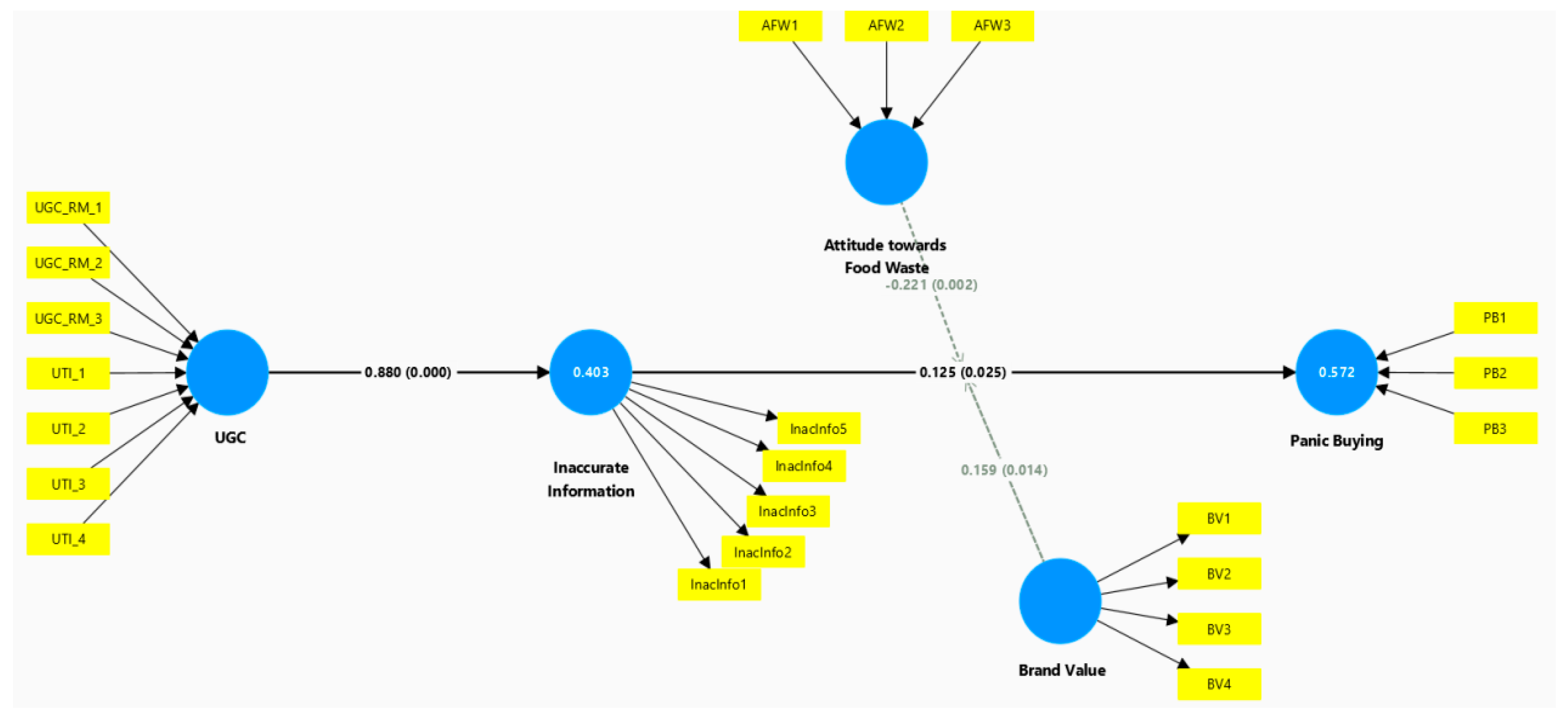

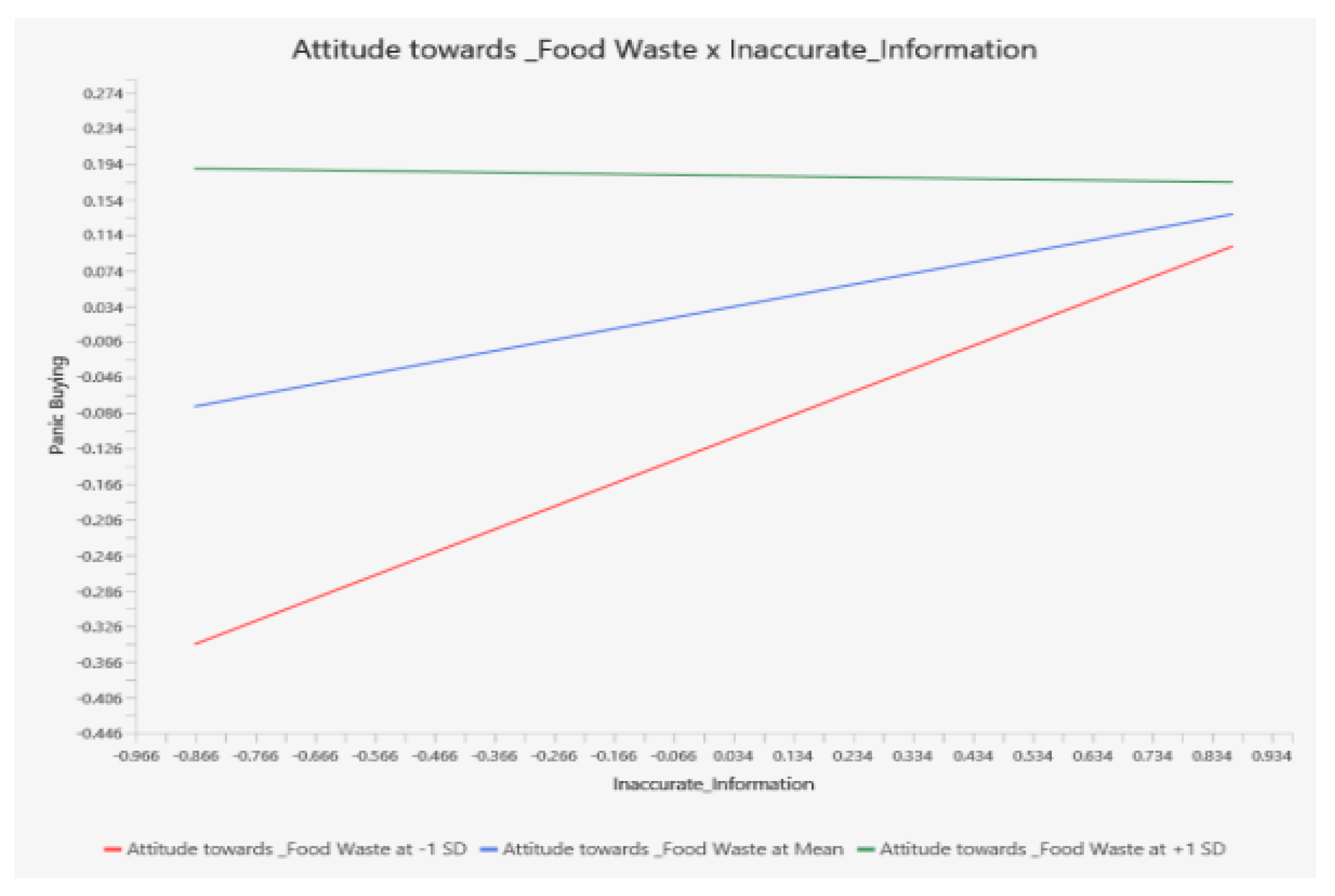

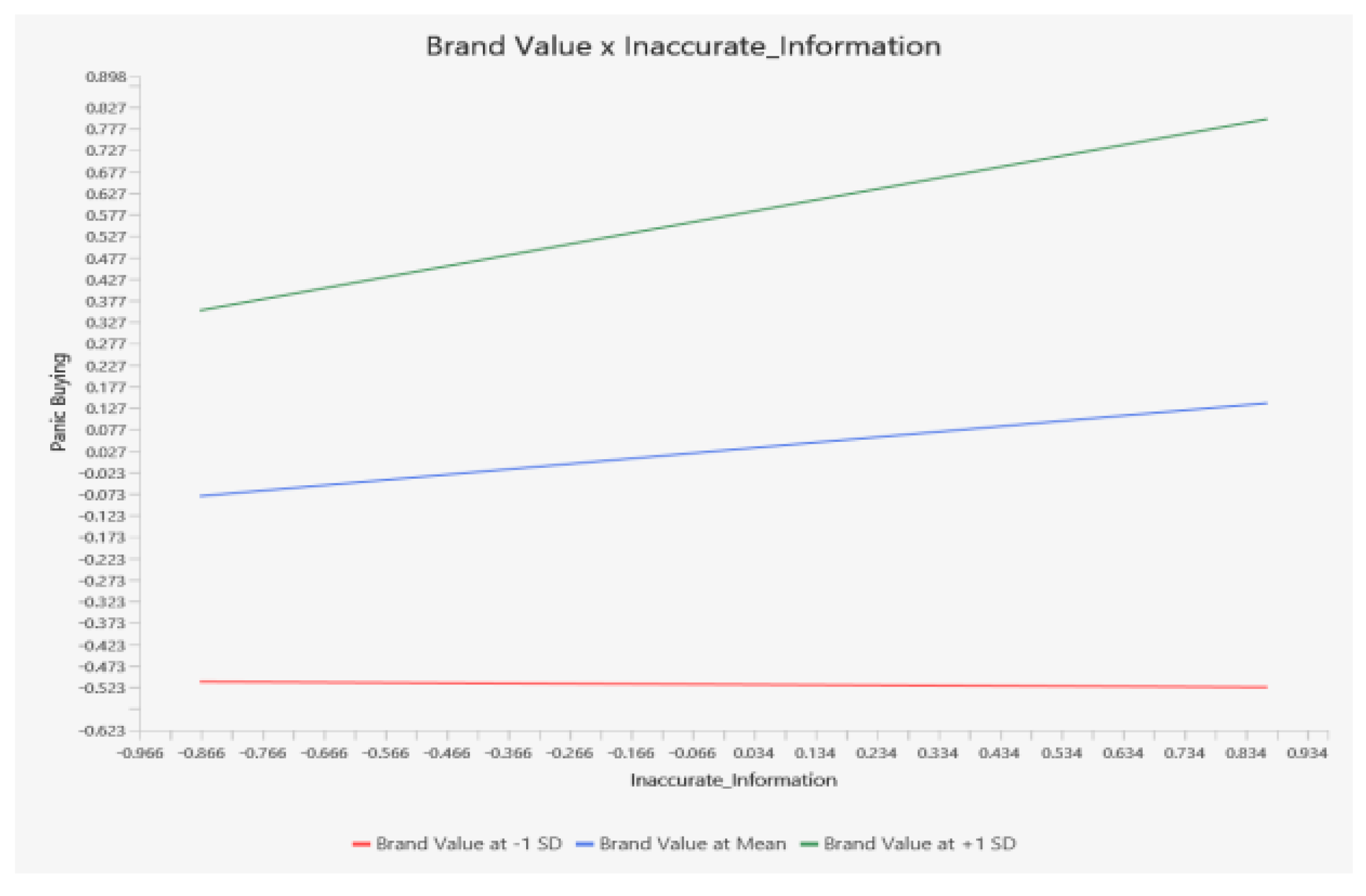

4.3. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fletcher, R.; Nielsen, R.K. Are people incidentally exposed to news on social media? A comparative analysis. New Media Soc. 2017, 20, 2450–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C. News Sharing on UK Social Media: Misinformation, Disinformation, and Correction. 2019. Available online: https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/report/News_sharing_on_UK_social_media_misinformation_disinformation_and_correction/9471269?file=17095679 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Farooq, A.; Dhir, A. Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.K.M.N.; Laato, S.; Talukder, S.; Sutinen, E. Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: An affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 159, 120201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B. Influence: Science and Practice; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; Volume 4, pp. 51–96. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The Extended Parallel Process Model. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Taha, V.; Pencarelli, T.; Škerháková, V.; Fedorko, R.; Košíková, M. The use of social media and its impact on shopping behavior of Slovak and Italian consumers during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roka, K. Environmental and social impacts of food waste. In Responsible Consumption and Production; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Borgne, G.; Sirieix, L.; Costa, S. Perceived probability of food waste: Influence on consumer attitudes towards and choice of sales promotions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 42, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehberger, M.; Kleih, A.-K.; Sparke, K. Panic buying in times of coronavirus (COVID-19): Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand the stockpiling of nonperishable food in Germany. Appetite 2021, 161, 105118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, L.; Russell, J.; Barker, M. Attitudes and behaviour towards convenience food and food waste in the United Kingdom. Appetite 2016, 103, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T. Waste: Uncovering the Global Food Scandal; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Definitions Misinformation—Disinformation. 2020. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Boyd 2009, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. The Implied Truth Effect: Attaching warnings to a subset of fake news stories increases perceived accuracy of stories without warnings. Manag. Sci. 2019, 66, 4944–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.C.; Lim, Z.W.; Ling, R. Defining “Fake News” A typology of scholarly definitions. Digit. J. 2018, 6, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R.K. Social media’s contribution to political misperceptions in U.S. presidential elections. J. Commun. 2019, 69, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Zafarani, R. Fake news: A survey of research, detection methods, and opportunities. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, K.; Wang, S.; Lee, D.; Liu, H. Mining disinformation and fake news: Concepts, methods, and recent advancements. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. (TOIS) 2020, 38, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Environmental concerns and food consumption: What drives consumers’ actions to reduce food waste? J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 31, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.B.E.; Geyskens, I. Manufacturer and retailer strategies to impact store brand share: Global integration, local adaptation, and worldwide learning. Mark. Sci. 2014, 33, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand equity as a signaling phenomenon. J. Consum. Psychol. 1998, 7, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Keller, K.L. Integrating marketing communications: New findings, new lessons, and new ideas. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Joachimsthaler, E. The brand relationship spectrum: The key to the brand architecture challenge. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, A.E.; Brodie, R.J. Chapter 7 Brand image, corporate reputation, and customer value. In Business-To-Business Brand Management: Theory, Research and Executivecase Study Exercises; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 263–387. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bougie, R.; Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Winton, B.G.; Sabol, M.A. A multi-group analysis of conve-nience samples: Free, cheap, friendly, and fancy sources. Int. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2022, 25, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Jin, M.H.; Kim, J.; Shin, N. User perception of the quality, value, and utility of user-generated content. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.J.; Johnson, K.K. Power of consumers using social media: Examining the influences of brand-related user-generated content on Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L.; Sia, J.K.M.; Tang, D.K.H. To verify or not to verify: Using partial least squares to predict effect of online news on panic buying during pandemic. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Pappas, I.O.; Metri, B.; Hughes, L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Fake news on Facebook and their impact on supply chain disruption during COVID-19. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 327, 683–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.J.F.; Bairrada, C.M.; Coelho, A.M. Functional brand qualities and perceived value: The mediating role of brand experience and brand personality. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, D.; Cramer, D. Introduction to SPSS in Psychology: With Supplements for Releases 10, 11, 12 and 13; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1526419521. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH. 2022. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural Equation Modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. In Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research; Hoyle, R., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hair, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Sinkovics, R., Ghauri, P., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Fami, H.S.; Aramyan, L.H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Alambaigi, A. Determinants of household food waste behavior in Tehran city: A structural model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakos, D.; Szabó-Bódi, B.; Kasza, G. Consumer awareness campaign to reduce household food waste based on structural equation behavior modeling in Hungary. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24580–24589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.H.; Memon, M.A.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Ramayah, T. Assessing reflective models in marketing research: A comparison between PLS and PLSC estimates. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Pitafi, A.H.; Arya, V.; Wang, Y.; Akhtar, N.; Mubarik, S.; Xiaobei, L. Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Characteristic | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 181 | 48.9% |

| Female | 189 | 51.1% | |

| Age | 16–25 | 24 | 6.5% |

| 26–35 | 117 | 31.6% | |

| 36–45 | 148 | 40.0% | |

| 46–55 | 54 | 14.6% | |

| 56+ | 27 | 7.3% | |

| Occupation | Unemployed | 6 | 1.6% |

| Public Worker | 93 | 25.1% | |

| Private Worker | 165 | 44.6% | |

| Entrepreneur/Self-employed | 79 | 21.4% | |

| Student | 6 | 1.6% | |

| Retiree | 21 | 5.7% | |

| Income(EUR) | 0–300 | 63 | 17.5% |

| (Monthly) | 301–600 | 21 | 5.8% |

| 601–900 | 72 | 19.9% | |

| 901–1200 | 99 | 27.4% | |

| 1201–1500 | 52 | 14.4% | |

| 1501–1800 | 42 | 11.6% | |

| +1801 | 12 | 3.3% |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)—Matrix | Fornell–Larcker Criterion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV | Inaccurate | BV × Inaccurate | AFW × Inaccurate | BV | Inaccurate | |

| BV | 0.647 | |||||

| Inaccurate | 0.580 | 0.430 | 0.754 | |||

| BV × Inaccurate | 0.119 | 0.419 | ||||

| AFW × Inaccurate | 0.129 | 0.455 | 0.708 | |||

| Dimensions and Items | CR | AVE | t-Value | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User- Generated Content | N/A | N/A | |||

| UTI_1 | I use the UGC on the social media for my personal satisfaction. | 3.259 (0.001) | 1.140 | ||

| UTI_2 | I use the UGC on the social media to get more viewpoints. | 5.533 (0.000) | 1.124 | ||

| UTI_3 | I use the UGC on the social media to exchange useful information freely. | 3.101 (0.000) | 1.152 | ||

| UTI_4 | I use the UGC on the social media to generate ideas. | 2.184 (0.001) | 1.161 | ||

| UGC_RM_1 | The postings that appear on the social media describe information about brands and news. | 3.818 (0.000) | 1.141 | ||

| UGC_RM_2 | The postings that appear on the social media fan pages describe values of the featured brands and products. | 1.979 (0.048) | 1.117 | ||

| UGC_RM_3 | The postings that appear on the social media fan pages describe benefits of the featured brands and products. | 3.262 (0.000) | 1.137 | ||

| Inaccurate Information | 0.868 | 0.568 | |||

| InacInfo1 | I check the source of online news content. (r) | 25.217 (0.000) | 1.437 | ||

| InacInfo2 | I always read the contents of online news, not just the headlines. (r) | 17.177 (0.000) | 1.946 | ||

| InacInfo3 | I usually check the date of online news to make sure the story is up to date. (r) | 12.297 (0.000) | 1.908 | ||

| InacInfo4 | I cross-check social media news against official media.(r) | 20.846 (0.000) | 2.158 | ||

| InacInfo5 | I seek expert opinions on the authenticity of online news. (r) | 27.205 (0.000) | 2.070 | ||

| Panic Buying | N/A | N/A | |||

| PB1 | I buy because everyone is buying. | 5.221 (0.000) | 1.290 | ||

| PB2 | I buy food and nonfood items more than what I normally bought | 3.774 (0.000) | 1.405 | ||

| PB3 | I buy according to how I feel | 7.520 (0.000) | 1.292 | ||

| I shop in the supermarket without thinking much *removed* | |||||

| Attitude towards Food Waste | N/A | N/A | |||

| AFW1 | In my opinion, wasting food is not at all negative (1) to extremely negative (5) | 7.586 (0.000) | 1.034 | ||

| AFW2 | I intend not to throw food away | 4.022 (0.000) | 1.347 | ||

| AFW3 | My goal is to throw food away. (r) | 4.974 (0.000) | 1.326 | ||

| Brand Value | 0.773 | 0.535 | |||

| BV1 | What I get from this brand is worth the cost. | 2.312 (0.021) | 1.091 | ||

| BV2 | All things considered (price, time, and effort), this brand is a good buy | 15.926 (0.000) | 1.182 | ||

| BV3 | Compared to other brands, this brand is good value for the money. | 28.164 (0.000) | 1.232 | ||

| BV4 | When I use this brand, I feel I am getting my money’s worth. | 10.205 (0.000) | 1.214 | ||

| Standard Bootstrap Results | Percentile Bootstrap Quartiles | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Path Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Stat | p-Value (2-Sided) | 2.50% | 97.50% | R2 | f2 | Conclusion |

| UGC → Inaccurate Information | 0.880 | 0.067 | 13.153 | 0.000 | 0.754 | 1.018 | 0.403 | 0.674 | Supported |

| Inaccurate Information → Panic Buying | 0.125 | 0.056 | 2.240 | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.229 | 0.572 | 0.016 | Supported |

| Attitude towards Food Waste × Inaccurate Information → Panic Buying | −0.221 | 0.072 | 3.095 | 0.002 | −0.363 | −0.076 | 0.031 | Supported | |

| Brand Value × Inaccurate Information → Panic Buying | 0.159 | 0.065 | 2.461 | 0.014 | 0.031 | 0.288 | 0.020 | Supported | |

| Attitude towards Food Waste → Panic Buying | 0.252 | 0.079 | 3.192 | 0.001 | 0.096 | 0.403 | 0.036 | ||

| Brand Value → Panic Buying | 0.659 | 0.060 | 11.015 | 0.000 | 0.553 | 0.789 | 0.582 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poulis, A.; Theodoridis, P.; Chatzopoulou, E. Sustainable Brand Resilience: Mitigating Panic Buying through Brand Value and Food Waste Attitudes Amid Social Media Misinformation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156658

Poulis A, Theodoridis P, Chatzopoulou E. Sustainable Brand Resilience: Mitigating Panic Buying through Brand Value and Food Waste Attitudes Amid Social Media Misinformation. Sustainability. 2024; 16(15):6658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156658

Chicago/Turabian StylePoulis, Athanasios, Prokopis Theodoridis, and Evi Chatzopoulou. 2024. "Sustainable Brand Resilience: Mitigating Panic Buying through Brand Value and Food Waste Attitudes Amid Social Media Misinformation" Sustainability 16, no. 15: 6658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156658

APA StylePoulis, A., Theodoridis, P., & Chatzopoulou, E. (2024). Sustainable Brand Resilience: Mitigating Panic Buying through Brand Value and Food Waste Attitudes Amid Social Media Misinformation. Sustainability, 16(15), 6658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156658