Abstract

Undeniably, COVID-19 disrupted higher education. The concepts of traditional learning were challenged, online learning was thrust into the mainstream in colleges and universities, and the student population was unavoidably affected. It became apparent that maintaining the status quo that existed prior to the pandemic was not the path to the future sustainability of higher education. As higher education institutions began the long road to recovery, important challenges emerged due to increased demand for online learning and emotional health concerns for students. The current research collected data from online undergraduates at private and public universities in the United States for multivariate data analyses to examine controllable elements in the online learning environment that can enhance student quality of life and psychological well-being. These elements relate to perseverance for students and may promote the sustainability of higher education institutions. The focus of this study is to emphasize the importance of reinforcing online students’ emotional health as an important sustainability strategy for higher education. The findings confirm that higher education institutions can facilitate online students’ quality of life and psychological well-being by implementing elements into the classroom that create procedural and interpersonal justice, which enhances the formation of social and structural bonds.

1. Introduction

Education has been an important component of the academic literature and discussions regarding sustainability. Much of the discussion logically focuses on the general idea that education is a powerful tool for helping societies sustain and thrive. Simply stated, education promotes sustainability [1]. While media headlines may question the value of a college degree [2,3], the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that college graduates earn more than those without a college degree, by as much as 68 percent [4]. Therefore, the sustainability of higher education is a worthy focus for academic research.

The concept of sustainability in higher education is multidimensional and could include both educating students about sustainability practices and addressing the sustainability of higher education. Not surprisingly, prior research in higher education has often focused on academic performance as the primary outcome of higher education [5,6,7,8]. It can be argued that the main reason for education is to enhance students’ academic knowledge and skills to prepare them for the job market [5,8]. Certainly, student academic performance can enhance or damage the reputation of an institution or instructor [5,7,8], making the sustainability of higher education an essential factor.

Student quality of life and well-being in higher education are focal points for academic success and the sustainability of higher education. During the pandemic, emotional health concerns became more prevalent with the prolonged impact of COVID-19 on the educational process, and the unplanned rapid shift to online classes or hybrid classes produced student anxiety that was less easily addressed remotely [5,6,7,9]. Students tended to feel unsafe, uncertain, and worried, which left institutions and instructors encumbered with identifying needs and providing support for students’ quality of life and psychological well-being [5,9]. Post-COVID, universities did not return to business as usual. Many academic institutions continue to experience a higher demand for online courses than before the pandemic [10], with incoming students having lower levels of preparation [11]. Given this, the emotional health of students in an online environment remains highly relevant for universities.

The psychological health of online students plays a crucial role in their ability to comprehend and process information in an academic environment, and improvements in this area could contribute to a more sustainable society [12]. This paper examines controllable instructional approaches in online classes that could directly impact student quality of life and psychological well-being. We explore constructs that previous research has indicated influence these elements of a student’s emotional health. From a theoretical perspective, our research applies the fundamental notions of perceived justice and relational bonds to the educational context based on the conceptual approach of previous studies to predict students’ quality of life and psychological well-being. Practical implications are provided.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Higher Education Sustainability

In the context of higher education, the concept of sustainability is multifaceted. Research by [13] highlighted the importance of sustainable change in academic institutions, while [14] indicated that students’ perceptions of academic fairness improved academic sustainability in terms of persistence to graduation. Additionally, sustainability and social justice have been described as having a symbiotic relationship in an educational context [15], and some studies have examined resources that would support integrating sustainability concepts into the curriculum [16]. Thus, higher education sustainability is a broad topic with various applications. In our study, the sustainability of higher education refers to the role of academic institutions in helping students persist toward graduation by reinforcing their quality of life and psychological well-being. Specifically, this research focuses on online students who access virtual resources and take classes remotely.

While the sustainability of higher education often implies the maintenance of vibrant campus communities and facilities, universities cannot ignore the significance of digital and remote learning. Online learning has become an inevitable part of the higher education landscape after COVID-19 [17]. Any future approach to successfully sustaining higher education must embrace the duality of universities, supporting both on-campus and online learning. Success may depend upon challenging traditional pedagogical methods and modifying tools for the online environment [17]. Building online learning environments that promote student achievement may require innovative approaches to old concerns. This involves providing adequate support for digital education, but, perhaps more importantly, offering resources that support both face-to-face and online student success [18].

The increased strains on student emotional health resulting from COVID-19 have created a new challenge for institutions of higher learning: to prioritize the well-being of all students. Sustainable higher education practices for the foreseeable future are likely to be predicated on the ability of college faculty to identify and understand psychological stressors affecting their students. A student’s quality of life and well-being may be partially derived from their conclusions regarding fairness and justice in the learning environment [14,19], thereby making the ability to influence their perceptions of classroom equality fundamental to the sustainability of higher education [20].

2.2. Perceived Justice

Perceived justice theory is based on the foundation of social exchange theory [21]. Specifically, individuals tend to perceive the fairness of relationships with others based on the balance in terms of the ratio between rewards received and effort spent in developing and maintaining the relationships [22]. Since individuals perceive their efforts spent in developing and maintaining relationships with others as valuable, they are more likely to be concerned about the fairness of the outcomes of the relationships.

Our research examines two aspects of perceived justice. First, procedural justice relates to how individuals perceive exchanges with others [23]. To enhance procedural justice, individuals must perceive exchanges as accurate, consistent, free of bias, and ethical [22]. For example, high procedural justice might be formed if instructors provide their students with fair procedures [23]. Second, interpersonal justice is based on how individuals perceive interactional fairness with others in a specific situation, and high interpersonal justice might be formed when expected levels of respect, politeness, honesty, and timely feedback from others are provided [22,24].

The literature regarding perceived justice in higher education builds upon earlier research from several authors [22,24,25]. In an online context, professors may integrate student peer-to-peer interactions as well as direct instructor-to-student interactions to achieve a more dynamic learning experience. When peer-to-peer interactions form the basis for any portion of performance assessment, students may assess the fairness of treatment from both their peer evaluators and their professor. This may cause students to consider how they are being treated by instructors and classmates regarding ethics, equality, equity, and discriminatory behavior in class.

Students’ justice perceptions significantly influence their academic outcomes as a psychological factor [24,25]. For example, prior research in the education field has discovered the influence of students’ justice perceptions on motivation and learning, instructor competence, teachers’ evaluation, and classroom policies [26,27,28,29]. Furthermore, there is an association between satisfaction and perceived justice [25] and satisfaction and fairness [30]. As such, it is important for a classroom environment to promote motivation and learning through fair treatment of students in class [25,29].

Based on perceived justice theory, there is a relationship between perceived unfair treatment and a student’s quality of life and overall well-being [22]. This can be extended to perceived fair or unfair treatment by peers. Despite this possibility, empirical studies on how students perceive justice in their interactions with classmates have been limited. Our research aims to explore the relationship between online students’ justice perceptions and their psychological states.

2.3. Relational Bonds

According to the social exchange theory, individuals may develop relationships with others to facilitate exchanges for both material and non-material goods and to engage in relationships that are rewarding and beneficial [21,31]. When the reward is greater, individuals are more likely to establish and sustain strong psychological relationships with others, such as relational bonds, to continuously gain competitive advantages or rewards [22]. When students experience fairness in their interactions with their instructor and peers, based on traits such as honesty, politeness, timely feedback, and respect, they are more likely to participate in class assignments and activities, thereby forming stronger bonds with the online class environment [32,33]. Students’ interpersonal relationships with their classmates and instructors can significantly influence their overall bonding with the online class, as positive communication and the sharing of experiences and opinions can foster a sense of community [33,34].

This study focuses on two types of relational bonds. First, relational bonds that create psychological benefits from social interactions or friendships with others who are in the same environment, such as online classes, are known as social bonds. This type of relational bond is developed by showing compassion for those in similar environments or situations to facilitate perceived closeness, connection, and mutual understanding [22]. In other words, individuals’ social bonds are exhibited by staying in touch, forming friendships, sharing information, and discussing opinions [31,35].

Second, relational bonds that offer information that is not easily obtainable from other relationships or sources are known as structural bonds [22,31]. Structural bonds are likely to be formed by the exchange of high-quality information and the adaptation and use of information-getting procedures [22,35]. In online classes, it is important to help students achieve success and solve academic problems by providing valuable online content and information. In this study, structural bonds refer to bonds formed when useful and supportive content and information provide students with academic solutions.

Because online communities often concentrate on sharing information [36,37,38], some of the education-focused research on relational bonds has compared education to non-academic online communities [22,36,38]. Similar to a traditional classroom where personal and interpersonal relationships are formed, online classes may utilize tools to achieve these same outcomes. Although the possible establishment of relational bonds in an online academic setting has been proposed, little empirical research has explored it [36,37,38]. Conceivably, students’ justice perceptions could have a significant effect on the development of relational bonds with online classes, consequently resulting in higher levels of quality of life and psychological well-being outside of online classes.

2.4. Quality of Life and Psychological Well-Being

Quality of life conceptually refers to individuals’ levels of independence, psychological state, physical health, and relationships with their environment’s salient features [39]. It is closely related to higher levels of satisfaction with an individual’s general life [40]. Perceived quality of life is formed by experiential and subjective evaluations of various factors such as consumption, family, personal health, work, and leisure [39,41]. In this research context, student quality of life is defined as students’ perceptions of their general life as a student within the settings of school and class cultures [41].

Psychological well-being refers to optimal human positive functioning [40]. Engagement, interest, meaning, purpose, optimism, self-acceptance, competence, respect, and supportive and rewarding relationships with others can help to achieve psychological well-being [42]. Based on the fundamental notion of need satisfaction, students’ psychological well-being can inspire them to complete assignments and exams in order to satisfy their actualization, knowledge, esteem, aesthetic, health and safety, and social needs [43]. According to research conducted by [44], students who form close bonds with their online classes experience an overall improvement in their quality of life and psychological well-being. This is due to the fact that social capital built through activities and interactions within the online class can help reduce feelings of loneliness and also provide students with valuable knowledge that can be applied to their everyday lives outside of the virtual classroom [45]. Overall, the online class is seen as a valuable resource for social capital, ultimately leading to a more positive experience for students [44,45].

2.5. Hypothesis Development

Higher education sustainability is examined in the context of student quality of life and psychological well-being as important factors of student persistence as well as a vital strategy for higher education sustainability. Our study empirically examines how to improve sustainability in higher education by focusing on the quality of life and well-being of online students. Based on previous research, it can be postulated that online students’ perceptions of justice and relational bonds impact their quality of life and psychological well-being. These perceptions are shaped by both their instructors and their classmates.

Drawing on previous research regarding justice, we hypothesize associations between perceived procedural justice and perceived interpersonal justice and the development of social and structural bonds with instructors and classmates. This research proposes the following hypotheses:

H1-1.

An instructor’s procedural justice is positively associated with social bonds with an online class.

H1-2.

An instructor’s procedural justice is positively associated with structural bonds with an online class.

H2-1.

Classmates’ interpersonal justice is positively associated with social bonds with an online class.

H2-2.

Classmates’ interpersonal justice is positively associated with structural bonds with an online class.

Similarly, based on previous research on relational bonds, we hypothesize associations between social and structural bonds and quality of life and psychological well-being. Accordingly, we offer the following hypotheses:

H3-1.

Social bonds with an online class are positively associated with quality of life.

H3-2.

Social bonds with an online class are positively associated with psychological well-being.

H4-1.

Structural bonds with an online class are positively associated with quality of life.

H4-2.

Structural bonds with an online class are positively associated with psychological well-being.

3. Materials and Methods

This study collected responses from 250 online undergraduate students at private and public universities in the United States using an online survey approach during the last week of March 2023. The study consists of 228 viable responses after excluding incomplete responses or those who failed an attention test. Using a convenience sampling procedure, instructors at public universities in the United States invited their online undergraduates to participate in an online survey for extra credit (approximately 1% of their grade). This study utilized a sample size calculator specifically designed for studies implementing a structural equation modeling approach (https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89) (accessed on 10 May 2024). This tool calculated the necessary sample size based on the structural complexity of the model, which included 22 observed variables and 6 latent variables, alongside an anticipated effect size of 0.1, with a desired significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8. The calculator determined that a minimum sample size of 123 participants was required for the given model parameters. Table 1 summarizes the methodological approach of our study.

Table 1.

Summary of the methodological approach.

The study sample was comprised of 68.4% female students (n = 156) and 31.6% male students (n = 72). In terms of academic standing, 31.1% of the sample were sophomores (n = 71), followed by seniors (n = 70, 30.7%), juniors (n = 47, 20.6%), and freshmen (n = 40, 17.5%). In terms of race/ethnicity, 50.4% of the sample were Caucasian (n = 115), 27.6% were African American (n = 63), 17.1% were Hispanic (n = 39), 4.4% were Asian (n = 10), and 0.4% were classified as “other” (n = 1).

Modified validated scales from previous research were used to conceptualize and operationalize constructs in this study (see Table 2). Multiple pilot tests were conducted with online undergraduates to revise the survey. To avoid common method variance (CMV) among survey participants [46], the measures were randomly ordered. All items except for the demographic characteristics were operationalized and measured using a seven-point Likert-type scale, with “1” representing “strongly disagree” and “7” representing “strongly agree.”

To ensure the reliability and validity of our research measures and measurement model, we followed a two-step approach developed by [47]. The Cronbach alpha coefficients of all the indicators were estimated using SPSS 28.0 and found to be satisfactory with values greater than 0.70. The values were as follows: (1) instructor’s procedural justice at 0.863; (2) classmate’s interpersonal justice at 0.800; (3) social bonds with an online class at 0.775; (4) structural bonds with an online class at 0.926; (5) quality of life at 0.971; and (6) psychological well-being at 0.976 [48].

Table 2.

Results of a confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 2.

Results of a confirmatory factor analysis.

| Constructs, Sources, and Items | Standardized Estimate | Critical Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Instructor’s procedural justice Source: [27,49] | ||

| My instructor’s teaching has been applied consistently in this online class. | 0.598 | Fixed |

| My instructor’s teaching has been free of bias in this online class. | 0.911 | 10.263 |

| Students in this online class have been able to express views and feelings about the instructor’s teaching. | 0.947 | 10.412 |

| The instructor’s teaching has upheld ethical and moral standards. | 0.670 | 8.387 |

| Classmate’s interpersonal justice Source: [27,49] | ||

| My classmates in this online class have treated me in a polite manner. | 0.816 | Fixed |

| My classmates in this online class have treated me with dignity. | 0.834 | 13.208 |

| My classmates in this online class have treated me with respect. | 0.699 | 10.863 |

| My classmates in this online class have refrained from improper remarks or comments. | 0.513 | 7.613 |

| Social bonds with online class Source: [22] | ||

| This online class keeps in touch with me and has established a good relationship. | - | - |

| This online class is concerned with my needs. | 0.601 | Fixed |

| This online class keeps me resolve problems regarding my study. | 0.767 | 8.240 |

| This online class asks my opinions about information. | 0.846 | 8.192 |

| Structural bonds with online class Source: [22] | ||

| This online class offers a variety of ways to get information more efficiently. | 0.885 | Fixed |

| This online class provides me with news or information that I need. | 0.950 | 21.855 |

| This online class provides information from other sources to resolve my problems. | 0.872 | 18.703 |

| Quality of life Source: [40] | ||

| While taking this online class, the conditions of my life are excellent. | 0.930 | Fixed |

| Since taking this online class, I have gotten the important things I want in life. | 0.937 | 27.715 |

| While taking this online class, I am satisfied with my life as a whole. | 0.958 | 29.637 |

| Since taking this online class, the quality of my life has been enhanced. | 0.958 | 29.684 |

| Psychological well-being Source: [40] | ||

| This online class satisfies my overall needs. | 0.980 | Fixed |

| This online class plays a very important role in my social well-being. | 0.932 | 33.783 |

| This online class plays a very important role in my psychological well-being. | 0.984 | 51.684 |

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to test the convergent validity of the indicators. One item was removed due to its standardized factor loading being lower than 0.50, maintaining acceptable validity. Respectively, the standardized factor loadings as well as critical ratios of all the constructs’ respective indicators were greater than 0.50 and 2.58 (p < 0.01). This confirms their validity, as shown in Table 2 [50]. In addition, the fit indices of the measurement model were generally acceptable in the social science contexts and reported as follows: (1) 599.460 for Chi-square with 174 degrees of freedom and p < 0.001; (2) 0.910 for incremental fit index (IFI); (3) 0.890 for Tucker–Lewis index (TLI); (4) 0.909 for comparative fit index (CFI); and (5) 0.074 for root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) [48]. To test the hypothesized paths between the constructs using structural equation modeling, the reliabilities and validities must be confirmed via reliability and confirmatory factor analyses according to the two-step approach [47,48].

3.2. Construct Intercorrelations

To ensure the reliability of the composite constructs (instructor’s procedural justice, classmate’s interpersonal justice, online social bonds, online structural bonds, quality of life, and psychological well-being), we estimated reliabilities based on the results of the confirmatory factor analysis. Reliabilities for the composite constructs were as follows: 0.869 for the instructor’s procedural justice, 0.813 for classmate’s interpersonal justice, 0.786 for social bonds with an online class, 0.930 for structural bonds with an online class, 0.971 for quality of life, and 0.976 for psychological well-being, all of which exceeded the threshold value of 0.70 [51]. Furthermore, the authors conducted a correlation analysis and assessed the average variance extracted values of each variable, and the discriminant validity was investigated via comparison of the average variance extracted values of each variable with their squared intercorrelations. The results, as shown in Table 3, confirmed the discriminant validity of all the variables in our study, where the squared intercorrelation coefficients were smaller than their respective average variance extracted values [51].

Table 3.

Construct intercorrelations (Φ) and average variance extracted.

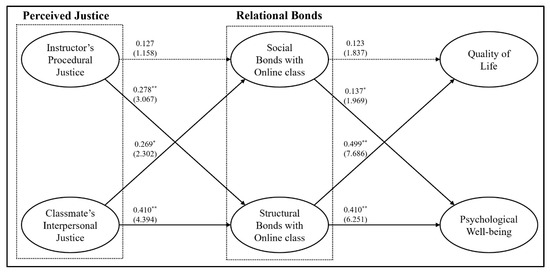

3.3. Structural Equation Modeling

After confirming reliability and validity, the hypothesized relationships were tested using structural equation modeling through AMOS 28.0 (see Figure 1). With this statistical approach, the authors could simultaneously predict the quality of life and psychological well-being constructs with the entire set of research hypotheses [48]. The squared multiple correlations shown in Table 4 indicate how well endogenous variables are empirically explained by exogenous variables (i.e., R square values in a regression analysis) and were reported as 0.153 for social bonds with an online class, 0.402 for structural bonds with an online class, 0.249 for quality of life, and 0.173 for psychological well-being. The following fit indices of the proposed model in our research were satisfactory for testing the research hypotheses [48]: (1) 604.833 for Chi-square with 112 degrees of freedom and p < 0.001; (2) 0.909 for IFI; (3) 0.892 for TLI; (4) 0.909 for CFI; and (5) 0.073 for RMSEA.

Figure 1.

Estimates of structural equation modeling. Note: Standardized estimate (critical ratio), ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Solid arrows: significant; dashed arrows: insignificant.

Table 4.

Standardized structural estimates.

4. Results

Overall, the results provide support for most of the hypotheses, as shown in Table 5. Hypotheses H1-1 and H1-2 pertain to procedural justice. An instructor’s procedural justice methods were expected to impact both social and structural bonds with online students. While procedural justice was significantly associated with structural bonds (β = 0.278, Se = 0.138, C.R. = 3.067, p < 0.01), it was not found to be associated with social bonds (β = 0.127, Se = 0.175, C.R. = 1.158, p > 0.05). These results provide support for H1-2. This result suggests that the fairness and consistency in the way an instructor administers rules and interacts might not be crucial for developing personal, social connections with students. This could be because online environments limit personal interactions, making it harder for procedural aspects to influence social relationships deeply. However, when instructors apply procedures fairly, it likely leads to better structured, predictable, and reliable interactions within the online classroom setting, enhancing the structural bonds. This could mean students feel more secure about course expectations and grading, contributing to a more effective learning environment.

Table 5.

Test of hypotheses.

Hypotheses 2-1 and 2-2 explore interpersonal justice. Classmates’ interpersonal justice approaches were also expected to impact both social bonds with an online class (β = 0.269, Se = 0.102, C.R. = 2.302, p < 0.05) and structural bonds with an online class (β = 0.410, Se = 0.078, C.R. = 4.394, p < 0.01). Support was found for H2-1 and H2-2. This finding underlines the importance of how students treat each other in fostering a supportive and friendly online community. Positive interactions and fairness among peers likely contribute to a sense of belonging and emotional support, which are crucial in remote learning environments. In addition, this outcome suggests that fair and respectful interactions among peers significantly enhance task-related connections and collaborative efforts in learning activities, leading to more effective group work and project collaboration.

Both quality of life and psychological well-being were expected to be influenced by social and structural bonds. Hypotheses H3-1 and H3-2 examine the influence of social bonds. Social bonds were found to influence psychological well-being (β = 0.137, Se = 0.030, C.R. = 1.969, p < 0.05) but not quality of life (β = 0.123, Se = 0.040, C.R. = 1.837, p > 0.05). Support was found for H3-2 only. This indicates that having strong social connections within the class can enhance students’ psychological well-being, possibly by providing emotional support and reducing feelings of isolation common in online learning. Additionally, this suggests that while social bonds may enhance well-being by offering emotional support, they might not significantly impact broader aspects of students’ lives outside the educational context.

Finally, hypotheses 4-1 and 4-2 consider structural bonds with quality of life (β = 0.499, Se = 0.041, C.R. = 7.686, p < 0.01) and psychological well-being (β = 0.410, Se = 0.029, C.R. = 6.251, p < 0.01), providing support for both H4-1 and H4-2. This indicates that well-structured relationships and clear expectations within the class contribute substantially to the overall life satisfaction of students, likely by reducing stress and providing a predictable learning environment. Also, this suggests that effective structural bonding, which includes clear roles, responsibilities, and expectations, can positively affect students’ mental health by reducing anxiety and improving focus and engagement in their studies.

5. Discussion

The findings from this research offer both theoretical and practical implications. The theoretical implications suggest pathways for future research. The practical implications provide suggestions for improving student quality of life and well-being to support sustainability in higher education.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Theoretically, this study aimed to emphasize the importance of online students’ quality of life and psychological well-being and identify their determinants within the online community context [22,36,38]. Relying on previous research, this study considered students’ perceptions of justice as a determinant of establishing important bonds with instructors and classmates [26,28,29]. This study applied the perceived justice theory and the concept of relational bonds in online communities to an online learning context. The goal was to formulate a research model that predicts online students’ quality of life and psychological well-being while being influenced by fair interactions with their instructors and classmates and the development of relational bonds in online classes. This new avenue enables researchers to apply the perceived justice theory in the digital learning context to improve online students’ quality of life and psychological well-being as one method for enhancing sustainability in higher education. Additionally, the concepts can be used to extend the research in higher education sustainability. Our study significantly enriches the theoretical landscape of online education by illustrating how distinct perceptions of procedural and interpersonal justice influence the formation of structural and social bonds among online students. The model proposed in our research underscores the critical role of emotional and psychological support networks in online learning environments [52]. Furthermore, applying social exchange theory to this context reveals how reciprocity in student interactions fosters a supportive learning environment, ultimately enhancing students’ quality of life and psychological well-being [53].

This study expands the boundaries of the perceived justice and social exchange theories in the online community context to the online education setting, considering the similar characteristics between the two [22,52,53]. Prior research has primarily focused on interactions between instructors and students rather than multi-sided interactions between students and classmates or the class itself [52,54]. In other words, while existing research has predominantly focused on the interactions between instructors and students, it has often overlooked the complex, multi-faceted interactions among students themselves and the collective interaction within the class as a whole [52,53,54]. Therefore, this study fills a gap by examining the role of justice perceptions in forming relational bonds and psychological states, and our research findings show that classmates’ interpersonal justice is more influential in establishing relational bonds than an instructor’s procedural justice [22,34,53,54,55]. This means that online students prefer to be fairly treated by their peers to build relational bonds with their online classes [54,55]. Specifically, this suggests a significant preference among online students for peer interactions that are perceived as fair, underscoring the importance of fostering an equitable and supportive peer culture within online classes. Such dynamics are crucial as they directly impact students’ sense of belonging and their overall engagement with the course material. As such, research in higher education sustainability might include these concepts. Scholars in the education field call for a re-evaluation of current educational practices and pedagogical strategies to emphasize and facilitate fair peer interactions as a fundamental component of course design. This shift could not only enhance the educational experience but also contribute to the psychological well-being and retention of students, thereby supporting the broader goals of educational sustainability.

Consistent with previous research on social exchange theory, our results demonstrated that an individual’s associations with an online environment could play a significant role in improving their quality of life and psychological well-being in and beyond the classroom [40,56]. Our research proposes a different approach to exploring the relationship between perceived justice, relational bonds, quality of life, and psychological well-being in the online education setting based on perceived justice and social exchange theories. These relationships support stronger sustainability in higher education. The implications of these findings are particularly significant for the sustainability of higher education. They suggest that fostering a just and reciprocal online environment is not merely a matter of ethical education practice but is also crucial for the psychological resilience and academic persistence of students. By strengthening the relational bonds through fair interactions, educational institutions can create more supportive and sustainable learning communities that enhance student outcomes and well-being. Thus, our research supports a shift in educational strategies towards integrating principles of justice and exchange into the design and management of online courses, thereby promoting a sustainable educational model that addresses both academic and psychological needs.

5.2. Practical Implications

The focus of this study is to emphasize the importance of reinforcing online students’ quality of life and psychological well-being as an important sustainability strategy for higher education. This study confirms that institutions can facilitate online students’ quality of life and psychological well-being by implementing elements into the classroom that create procedural and interpersonal justice, which enhances the formation of social and structural bonds. Previous research confirms the importance of quality of life and psychological well-being in improving academic persistence and achievement. Both student persistence and achievement serve to strengthen the academic institution. Traditional classroom methods must be extended and potentially modified to achieve desired outcomes with online students. For example, online instructors can use automated tools that provide timely and uniform feedback on quizzes and assignments, thereby reducing any perception of bias (i.e., procedural justice). Furthermore, online instructors can implement regular virtual office hours and Q&A sessions that allow students to feel heard and supported, which enhances their trust in the fairness of the educational process. Interpersonal justice can also be facilitated through structured peer-review systems where online students are trained to provide constructive feedback respectfully. Online platforms need to include community-building activities such as virtual group projects that require collaboration, ensuring that each member contributes equally, supported by tools like collaborative software (e.g., Google Workspace or Microsoft Teams) that track contributions. These activities help in creating a supportive community atmosphere, which is crucial for student well-being.

The findings from this study would suggest that practicing procedural fairness as an instructor can strengthen online students’ connections to their classes, thereby promoting students’ quality of life and psychological well-being. As a strategy for sustainability, higher education instructors should maintain consistency in their teaching and course policies, without showing favoritism to any particular student or groups of students. To facilitate this, instructors should consider providing clear procedures describing limitations and requirements for deviations from stated class policies and procedures (e.g., rules regarding missed tests, appropriate university policies regarding ADA accommodations, etc.). For example, online instructors could create a comprehensive digital handbook that is accessible throughout the course, detailing steps and protocols for common scenarios such as missed tests or late submissions. Post-course evaluations, exit surveys, and alumni surveys might be used to gather feedback to identify any instances of perceived unfairness. While instructors are encouraged to listen to feedback offered from students unprompted, feedback from current students should only be requested with portals ensuring anonymity. For instance, using digital platforms like SurveyMonkey or Google Forms, instructors can collect anonymous evaluations that allow students to express their views on the fairness of grading practices and the clarity of course instructions. Instructors should not only collect feedback but also actively respond to it. This includes making adjustments to teaching practices where fair concerns are raised. Follow-up communication can be sent to the class explaining any changes made in response to the feedback, thereby enhancing transparency and trust. Creating an environment where students feel protected and supported to share their concerns might improve perceptions of fairness and trustworthiness, leading to stronger bonds and better student quality of life and overall well-being, ultimately improving sustainability.

Given that our study yielded empirical results encouraging online students to form social and structural bonds with their classmates, facilitating harmonious relationships among students through procedures that ensure fairness is warranted. Although it can be more difficult to replicate classroom interactions in an online environment, this study would suggest that online students need positive interactions with their peers and instructor. A variety of methods might be employed to reduce conflict and enhance amenable collaboration, such as using group contracts, establishing communication guidelines, etc.). Instructors are encouraged to provide conflict resolution methods for online classrooms. More specifically, group contracts for collaborative projects could delineate each member’s responsibilities, set clear deadlines, and define processes for managing non-compliance. Establishing such clear expectations from the outset promotes equitable participation and respectful engagement among students, thereby reducing potential conflicts and enhancing group dynamics. Additionally, the development and enforcement of comprehensive communication guidelines are vital. These guidelines should cover norms for online discussions, including respect for diverse viewpoints, constructive responses to peers, and appropriate digital communication etiquette. By setting these standards, instructors can foster a safe and inclusive online environment that encourages positive interactions and supports diverse student needs. By integrating these strategies into online courses, instructors significantly enhance collaborative experiences. This proactive approach to managing online interactions and ensuring fairness contributes to a more engaging and supportive learning environment, ultimately improving student satisfaction and educational outcomes.

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While there appears to be an established pathway from student success to persistence and from persistence to sustainability in higher education, future research should attempt to enhance our knowledge. Identifying predictors of higher education sustainability requires a passage of time demonstrating the characteristics of students who persisted and those who did not and exploring institutions that closed and those that remained open. To gather relevant information more quickly, detailed exit surveys might shed light on issues leading to leaving higher education.

From a conceptual perspective, this study classified online students’ justice perceptions as instructors’ procedural justice and classmates’ interpersonal justice and relational bonds as social and structural bonds with online classes, based on the extant literature in the online community context. Even though similarities exist between online classes and online communities, this study might have overlooked the education-focused dimensions of online students’ perceived justice and relational bonds, such as instructors’ tenure (e.g., work experiences in academia) and class policies. Future research should utilize both in-depth interviews with online students and instructors and anonymous surveys to better identify undiscovered aspects of online students’ perceptions of justice and relational bonds. Concepts derived from researching online communities might have neglected nuanced aspects of higher education.

This study could be expanded to include the influence of the cultural and personal backgrounds of online students as they relate to perceptions of justice. One potential approach would be to include students taking online classes from institutions located outside of the United States. Using the proposed model, future research might involve multi-cultural studies (e.g., United States vs. Europe vs. Asia), extending the scope of higher education sustainability research to a broader context. Studies could also be expanded to examine school-related variables, such as size or type of institution and/or student personal characteristics such as income or job status.

6. Conclusions

While previous studies have explored sustainability in higher education, this study offers an important extension by including measures and predictors of the quality of life and psychological well-being of online students. This research investigated the key drivers of quality of life and psychological well-being among students who have taken online classes and offers important insight into improving the welfare of online students. Post-COVID, this is an increasingly important student population contributing to the sustainability of many tuition-driven institutions. Students’ perceptions of justice in the classroom impact the relational bonds that are formed, which in turn predicts students’ perceptions of their emotional health. Therefore, our research examines ways to build stronger relational bonds between online students, their peers, and instructors to support quality of life and well-being as a contributor to higher education sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., N.D.A., T.L.K. and J.K.; methodology, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, N.D.A. and T.L.K.; visualization, M.K., N.D.A., T.L.K. and J.K.; project administration, M.K., N.D.A. and T.L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Louisiana State University Shreveport for studies involving humans (LSUS 2022-0018).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Foster, J. Education as sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, S. Was Your Degree Really Worth It? Crunching the Puny Financial Benefits of Many University Courses. Available online: https://www.economist.com/international/2023/04/03/was-your-degree-really-worth-it (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Tough, P. Americans Are Losing Faith in the Value of College. Whose Fault Is That? Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/05/magazine/college-worth-price.html (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Andrews, G. Is College Worth It? Available online: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/education/student-resources/is-a-college-degree-worth-it/#:~:text=College%20graduates%20still%20enjoy%20higher (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- El Said, G.R. How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect higher education learning experience? An empirical investigation of learners’ academic performance at a university in a developing country. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Hernández-García, Á.; Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Prieto, J.L. Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandasari, B. The impact of online learning toward students’ academic performance on business correspondence course. EDUTEC J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 4, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, C.F.; Cascallar, E.; Kyndt, E. Socio-economic status and academic performance in higher education: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Hew, K.F.; Bai, S.; Huang, W. Adaptation of a conventional flipped course to an online flipped format during the Covid-19 pandemic: Student learning performance and engagement. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, L. Students Distancing from Distance Learning. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2024/01/30/online-college-enrollment-continues-post-pandemic#:~:text=Online%20enrollment%20is%20seeing%20a (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Knox, L. Is the Covid Generation Ready for College? Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/covid-generation-ready-college?cmp=1 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Llurba, C.; Fretes, G.; Palau, R. Classroom Emotion Monitoring Based on Image Processing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, M.E. Organizational Learning Is Essential to Achieving and Sustaining Change in Higher Education. Innov. High. Educ. 2003, 28, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.; Petocz, P.; Taylor, P. Business students’ conceptions of sustainability. Sustainability 2009, 1, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketschau, T. Social justice as a link between sustainability and educational sciences. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15754–15771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, P.B.; Wals, A.E.J. Higher Education and the Challenge of Sustainability: Problematics, Promise, and Practice; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfoodh, H.; AlAtawi, H. Sustaining Higher Education through eLearning in Post COVID-19. In Proceedings of the 2020 Sixth International Conference on E-Learning, Sakheer, Bahrain, 6–7 December 2020; pp. 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbobaniyi, O.; Srivastava, S.; Oyetunji, A.K.; Amaechi, C.V.; Beddu, S.B.; Ankita, B. The mediating effect of perceived institutional support on inclusive leadership and academic loyalty in higher education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizzio, A.; Wilson, K.; Hadaway, V. University students’ perceptions of a fair learning environment: A social justice perspective. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2007, 32, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Idris, M.; Amin, R.U. Leadership style and performance in higher education: The role of organizational justice. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 26, 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Justice in social exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. The effects of perceived online justice on relational bonds and engagement intention: Evidence from an online game community. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, R.; Tatum, N.T. Examining direct and indirect effects of classroom procedural justice on online students’ willingness to talk. Distance Educ. 2018, 39, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasooli, A.; Zandi, H.; DeLuca, C. Conceptualising fairness in classroom assessment: Exploring the value of organisational justice theory. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2019, 26, 584–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, N.V.; Cho, Y.C. Exploring effects of perceived justice and motivation on satisfaction in higher education. East Asian J. Bus. Econ. 2021, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, C.; Fernández, A.V. Relationships between the dimensions of organizational justice and students’ satisfaction in university contexts. Intang. Cap. 2017, 13, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chory, R.M. Enhancing student perceptions of fairness: The relationship between instructor credibility and classroom justice. Commun. Educ. 2007, 56, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplaga, E.A.; Astani, M. An exploratory study of student perceptions of which classroom policies are fairest. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2010, 8, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A. Examining the interplay of justice perceptions, motivation, and school achievement among secondary school students. Soc. Justice Res. 2016, 29, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msosa, S.K.; Fuyane, N. Making sense of service recovery in higher education institutions: Exploring the relationship between perceived justice and recovery satisfaction. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2020, 1, 340–352. [Google Scholar]

- Lioukas, C.S.; Reuer, J.J. Isolating trust outcomes from exchange relationships: Social exchange and learning benefits of prior ties in alliances. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1826–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.L.; Hope, E.C.; Matthews, J.S. Black and belonging at school: A case for interpersonal, instructional, and institutional opportunity structures. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 53, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L.; Mameli, C. Basic psychological needs and school engagement: A focus on justice and agency. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiouras, I.; Skourtis, G.; Giannopoulos, A.; Buhalis, D.; Karaosmanoglu, E. Testing the relationship between value co-creation, perceived justice and guests’ enjoyment. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, D.A.; Coughlan, R. Stakeholder relationship bonds. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspelin, J. Teaching as a way of bonding: A contribution to the relational theory of teaching. Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 53, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, E.; Rousell, D.; Jäger, N. Relational architectures and wearable space: Smart schools and the politics of ubiquitous sensation. Res. Educ. 2020, 107, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E. A light in students’ lives: K-12 teachers’ experiences (re) building caring relationships during remote learning. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Zheng, Q.; Fan, X. The impact of online social support on patients’ quality of life and the moderating role of social exclusion. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. How does a celebrity make fans happy? Interaction between celebrities and fans in the social media context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.J.; Pereira, R.; Freire, I.V.; de Oliveira, B.G.; Casotti, C.A.; Boery, E.N. Stress and quality of life among university students: A systematic literature review. Health Prof. Educ. 2018, 4, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Hou, H.; Peng, K. Effect of growth mindset on school engagement and psychological well-being of Chinese primary and middle school students: The mediating role of resilience. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, M.; Koo, D. From teamwork to psychological well-being and job performance: The role of CSR in the workplace. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3764–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, Y. College students’ social media use and communication network heterogeneity: Implications for social capital and subjective well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, S.; Cisheng, W.; Khan, A.N.; Khan, N.A. WhatsApp use and student’s psychological well-being: Role of social capital and social integration. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 103, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Assumptions and comparative strengths of the two-step approach: Comment on Fornell and Yi. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 20, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Horan, S.M.; Chory, R.M.; Goodboy, A.K. Understanding students’ classroom justice experiences and responses. Commun. Educ. 2010, 59, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Baek, T.H. I’ll follow the fun: The extended investment model of social media influencers. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 74, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, B.; Bannister, J.; Garza, G.; Rhame, S. A class of one: Students’ satisfaction with online learning. J. Educ. Bus. 2021, 96, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, T.; Poncin, I.; Hammedi, W.; Kullak, A.; Hollebeek, L.D. When gamification backfires: The impact of perceived justice on online community contributions. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 550–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, D. The impact of online learning during COVID-19: Students’ and teachers’ perspective. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2020, 8, 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Corbelli, G.; Cicirelli, P.G.; D’Errico, F.; Paciello, M. Preventing prejudice emerging from misleading news among adolescents: The role of implicit activation and regulatory self-efficacy in dealing with online misinformation. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sánchez, B.; Pascucci, T.; Di Pomponio, I.; Cedeño, G.G. Virtual education modality and digital competence in university students: Virtual learning methodologies at the university. In Perspectives on Innovation and Technology Transfer in Managing Public Organizations; Igi Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 154–175. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).