Abstract

United States (U.S.) and global experts recommend that populations reduce red and processed meat (RPM) intake and transition to plant-rich, sustainable diets to support human and planetary health. A systematic scoping review was conducted to identify the landscape of media campaigns that promote plant-rich dietary patterns, traditional plant proteins, and novel plant-based meat alternatives (PBMA) and that encourage or discourage RPM products to Americans. Of 8321 records screened from four electronic databases, 103 records were included, along with 62 records from gray literature sources. Across 84 media campaigns (1917–2023) identified, corporate marketing campaigns (58.6%) were most prevalent compared to public information (13.8%), corporate sustainability (12.6%), countermarketing (5.7%), social marketing (4.6%), and public policy (4.6%) campaigns. Findings indicate that long-running corporate RPM campaigns, many with U.S. government oversight, dominated the landscape for decades, running alongside traditional plant protein campaigns. Novel PBMA campaigns emerged in the past decade. Many civil society campaigns promoted plant-rich dietary patterns, but few utilized social norm or behavior change theory, and only the Meatless Monday campaign was evaluated. The U.S. government, academia, businesses, and civil society should commit more resources to and evaluate the impact of media campaigns that support a sustainable diet transition for Americans, restrict and regulate the use of misinformation in media campaigns, and prioritize support for plant-based proteins and plant-rich dietary patterns.

1. Introduction

U.S. and global expert bodies have recommended that individuals and populations, particularly those in high-income countries, shift their dietary patterns to reduce red and processed meat (RPM) intake and increase the consumption of whole, plant-based foods (i.e., fruits, vegetables, grains, pulses, nuts, and seeds) to support human health, reduce diet-related non-communicable diseases, and decrease environmental harms [1,2,3,4,5]. Yet U.S. consumers are confused about how the foods and beverages that they purchase and consume may impact their personal health, the environment, and the planet [6]. This confusion is largely due to marketing and media influences, such as conflicting information shared on social media platforms and the widespread use of environmental- and health-related labels and claims on food and beverage products and in advertisements [7,8,9]. The U.S. marketplace presents consumers with competing advertising and marketing messages from the meat industry, plant-based protein companies, and government and civil society organizations about the sustainability and health benefits of RPM, plant-based foods, and novel plant-based meat alternatives (PBMA) [10]. As a result, American consumers must navigate a complex ecosystem of conflicting messages to inform food purchasing and consumption decisions that support human and planetary health.

Corporations, public health practitioners, and policymakers have used media campaigns for decades to change diet- and health-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors [11,12]. The food and beverage industry has also used media campaigns as part of a corporate playbook [13] to build consumer awareness and brand loyalty for products to maximize economic growth, sales, and revenue. Likewise, agri-food industry actors have used campaigns to gain consumer trust by highlighting corporate social responsibility or social purpose activities to dispel concerns around the negative health, social, and/or environmental externalities associated with overconsuming their branded products and services [14]. Memorable advertising, education, and social change campaigns have been proposed as a potential strategy to shift consumers’ behaviors towards more sustainable products and dietary patterns within a broader policy, systems, and environmental change approach [1,15].

1.1. Sustainable Diet Transitions for Americans

The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) define a sustainable diet as encompassing dietary patterns that support human health and well-being for current and future generations; minimize environmental impacts and preserve biodiversity; and are affordable, accessible, safe, equitable, and culturally acceptable [16]. Many dietary patterns (e.g., Mediterranean, flexitarian, vegetarian, and vegan) align with this broader definition of a sustainable diet [17]. These patterns are collectively described as plant-rich dietary patterns and emphasize the intake of high-quality, diverse plant-based foods and encourage limited or no consumption of animal-sourced proteins, particularly RPM products linked to adverse health outcomes [1,3,17]. U.S. consumer studies over the past decade have indicated that few Americans follow plant-rich dietary patterns, but interest in sustainable dietary behaviors is growing [6,17].

Most American adults consume a Western diet that is characterized by the overconsumption of saturated and trans fats, RPM and other animal-based food and beverage products, sodium, added sugars, and highly processed foods, and the underconsumption of whole grains, pulses, vegetables, fruits, and nuts and seeds [18,19]. This pattern does not align with sustainable diet principles. In contrast, plant-rich dietary patterns are associated with a lower environmental impact and reduced risk of non-communicable disease-related morbidity (i.e., cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers) and all-cause mortality [19,20]. A sustainable diet transition involves shifting production and consumption practices to support human and planetary health and is often described in the context of shifting dietary practices to reduce meat and dairy intake and increase consumption of plant-based products [21,22,23].

The 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) report includes three dietary patterns (i.e., the Healthy U.S.-Style, the Healthy Mediterranean-Style, and the Healthy Vegetarian) [18]. All three DGA-recommended patterns recommend lower red meat consumption than the current average American intake level [24], and the DGAs discourage processed meat intake [18]. Yet the DGA-recommended Healthy U.S.-Style and Healthy Mediterranean-Style patterns may not have environmental benefits over current U.S. dietary patterns, largely due to their high red meat allotment [24].

1.2. U.S. RPM Product Market Trends

The U.S. is the world’s largest beef producer and consumer [25,26] and, correspondingly, one of the countries with the highest total red meat intake [27]. Beef and other red meat sources are rich in certain nutrients that are vital for human health, but RPM products are also often high in saturated fat, sodium, additives (e.g., nitrates and nitrites), and calories [28,29]. The large-scale industrialized production of animal agriculture, especially beef and, to a lesser extent, pork, are major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions [30], terrestrial acidification, and eutrophication that deplete land and water resources and contribute to biodiversity loss [31,32,33]. Additionally, these animal agriculture practices are linked to animal welfare concerns, antimicrobial resistance, and zoonotic disease transmission [34,35]. More than 80% of the U.S. beef market is controlled by four meatpackers—Tyson Foods, JBS USA, Cargill, and National Beef [36,37]. In addition to controlling much of the RPM market, these four U.S. meatpackers have invested substantially in highly processed PBMA and cultivated meat products, such as Tyson Foods and Cargill, that have launched their own PBMA product lines [38,39].

1.3. U.S. Plant-Based Protein Market Trends

Traditional plant-based protein foods such as pulses (i.e., beans, peas, and lentils), nuts, and seeds have been staple food products in dietary patterns in countries worldwide for centuries [40]. PBMA products that aim to mimic the appearance, taste, texture, and overall sensory eating experience of traditional meat products have proliferated in the U.S. marketplace over the past two decades [41,42].

Novel PBMA products have been proposed as more sustainable alternatives to conventional meat products [39,43,44,45]. However, U.S. consumers and experts have diverse views about these products’ contribution to a healthy and environmentally sustainable diet [6,10,34,41]. Additionally, research on the benefits of these products over animal-sourced proteins has been largely funded or commissioned by the PBMA industry [34]. The novel PBMA market in the U.S. is dominated by Beyond Beef and Impossible Foods, which grew by 43% to 1.4 billion U.S. dollars (USD) in sales between 2019 and 2022 [39]. Yet these sales equate to just 1.3% of total U.S. meat retail dollar sales [39]. U.S. consumer interest in PBMA products is growing [17], with the global PBMA market expected to reach USD 30.6 billion by 2032 [46].

1.4. Integrated Media Campaigns

The American Marketing Association defines integrated marketing communications as “a planning process designed to assure that all brand contacts received by a customer or prospect for a product, service, or organization are relevant to that person and consistent over time” [47]. Integrated marketing communications involves the strategic unification of various marketing communications strategies (i.e., advertising, brand visibility, sales promotion, digital platforms, public relations, and personal contact) to create a singular brand identity and to deliver messages more strategically and effectively [48]. These strategies are integrated across multiple media outlets, including digital (i.e., websites, blogs, social media, and texts); broadcast (i.e., radio, television, and cinema); print (i.e., newspapers, magazines, brochures or flyers, and posters); and outdoor/physical media (i.e., billboards, sides of buses, and sporting venues) [48]. For this study, an integrated media campaign was defined as a series of coordinated activities or messages (e.g., advertisements) shared through multiple digital and/or traditional print or broadcast media channels and platforms that were collectively identified through a unique name or slogan [11].

1.5. Study Purpose

To the authors’ knowledge, no study has systematically identified and described the different types of media campaigns used by diverse food systems stakeholders to encourage a sustainable diet transition for Americans. Identifying the breadth of such media campaigns can inform where and how sustainability campaigns may fit into the U.S. and international media and policy landscape and how these campaigns may influence consumers’ sustainable diet-related attitudes and behaviors. This study aimed to explore, organize, and describe the landscape of relevant U.S. and global media campaigns that promoted plant-rich dietary patterns, PBMA, and traditional plant-based proteins, and those that promoted or discouraged the purchase or consumption of RPM products to Americans.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was guided by the following four research questions (RQ):

- RQ1.

- What media campaigns have been launched to encourage Americans to adopt or maintain a Western diet by promoting the purchase or consumption of RPM products?

- RQ2.

- What media campaigns have been launched to encourage Americans to adopt or maintain a sustainable diet by promoting plant-rich dietary patterns, RPM reduction or replacement, or the purchase or consumption of traditional or novel plant-based proteins?

- RQ3.

- How can these media campaigns be classified into an established media campaign typology to assess their prevalence for promoting sustainable diet transitions?

- RQ4.

- What evidence is available to evaluate the effectiveness of these media campaigns to influence cognitive, behavioral, policy, and social norm outcomes?

2.1. Search Strategy, Evidence Selection, and Extraction

A systematic scoping review was conducted to capture relevant media campaigns guided by the five steps in the scoping study framework described by Arksey & O’Malley 2005 [49] that included the following: (1) identify the research question(s), (2) find relevant evidence that meets the inclusion criteria, (3) extract relevant evidence, (4) synthesize and interpret the evidence, and (5) compile, summarize, and share the results in a narrative summary. This study followed the reporting guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extention for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Figure S1) [50]. The lead researcher (K.C.S.) worked with Virginia Tech research librarians to design the scoping review search strategy.

Four interdisciplinary electronic databases were searched that index resources relevant to health (i.e., PubMed), communication (i.e., Communication and Mass Media Complete), agriculture, nutrition, and environmental sciences (i.e., AGRICOLA), and business (i.e., Business Source Complete). Title, abstract, and keyword searches, as applicable, were conducted from the database inception to 31 October 2023 to identify relevant evidence. An initial search was conducted in January 2023, with follow-up searches conducted to identify additional articles published between January and October 2023. Google Scholar was also searched using incognito mode, with the first 200 results considered for inclusion in the initial search, in line with recommendations for capturing gray literature sources for systematic reviews [51], and 50 results considered for inclusion in the follow-up search. Given the rise in novel plant-based food and beverage products over the past five years [52], it was anticipated that the published literature had not yet comprehensively described media campaigns for novel PBMA products. Iterative Google searches were, therefore, also conducted to identify campaigns described in media stories and other gray literature sources. Searches were conducted between 19 July and 31 October 2023.

Media campaigns that promoted plant-rich dietary patterns, traditional plant proteins, and novel PBMA products were included, as were campaigns that encouraged or discouraged the purchase or consumption of RPM products. Table 1 summarizes the detailed scoping review inclusion and exclusion criteria, while Table S1 provides the search terms used for each database and platform. For this study, RPM campaigns considered for inclusion were those that encouraged or discouraged products that aligned with the WHO definitions for red meat (i.e., beef, veal, lamb, pork, and goat) and processed meat products (i.e., mammalian muscle meat that has been salted, fermented, cured, smoked, or undergone other processes meant to enhance flavor or improve preservation) [53].

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the media campaign scoping review.

Traditional plant protein campaigns considered were those that promoted products that aligned with the 2020–2025 DGA protein category (i.e., pulses [beans, peas, and lentils], nuts, and seeds) [18]. While increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains is a component of plant-rich dietary patterns, U.S. and global campaigns with solely this focus (i.e., Five a Day for Better Health, Fruits & Veggies—More Matters) were considered beyond the scope of this study and have been described elsewhere [54]. Novel PBMA products were defined as those that were designed to mimic the sensory attributes of RPM products [41,42]. Campaigns for cultivated or cultured meat products, defined as products that are produced in a lab using animal stem cells grown in bioreactors [34], were beyond the scope of this study. This study focused on campaigns developed by producers, processors, the U.S. government, and civil society organizations. Restaurant and fast food campaigns for meat or plant-based protein products were considered beyond the scope of this campaign; major fast-food companies, in particular, have a deep history of campaign rivalry and consumer brand support that warrants an independent study [55].

K.C.S. conducted the scoping review searches and compiled the published and gray literature sources in Covidence, a web-based systematic review management platform [56]. K.C.S. conducted title and abstract screenings on all sources for alignment with the inclusion criteria. Two researchers (K.C.S. and N.L.) then independently conducted full-text screenings to confirm that sources met the inclusion criteria. As needed, independent Google searches were conducted to confirm that the campaigns mentioned in specific sources met the definition of an integrated media campaign. Disagreements between the two reviewers were reconciled through independent review and discussion with a third co-investigator (V.I.K.). Additional iterative Google searches for gray literature articles were conducted by K.C.S. and V.I.K. to identify potentially relevant media campaigns. Media campaigns were independently reviewed and categorized by three co-investigators (K.C.S., N.L., and V.I.K.) who met to share their categorizations, discuss differences in interpretations, and reach a consensus on the justification for each media campaign’s categorization.

2.2. Media Campaign Categorization and Outcome Identification

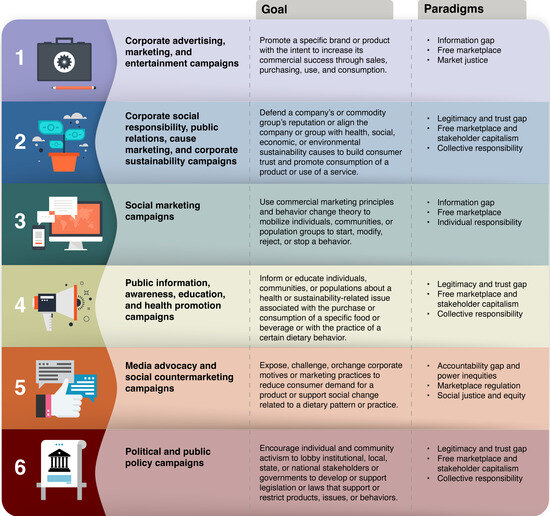

A media campaign typology was used to organize the evidence into six categories based on the campaign’s goal and paradigms (Figure 1) that was adapted from Kraak and Consavage Stanley 2021 [11]. The typology was initially developed to categorize beverage media but is grounded in research on campaigns that have influenced consumer awareness and perceptions of and behaviors towards alcohol, tobacco, and food and beverage products more broadly [11] and was, therefore, relevant for use in this study. Minor changes to the media campaign typology were guided by the researchers’ experience with sustainable diets and food systems and the existing literature on sustainability campaigns. Changes included the addition of “corporate sustainability” language to category 2, updating “countermarketing campaigns” to “social countermarketing campaigns”, and adapting the language used for media campaign goals to reflect that campaigns may have a focus beyond health outcomes to address other sustainability domains (i.e., environmental, social, and/or economic).

Figure 1.

A typology of media campaigns to encourage sustainable diet transitions that support human and planetary health.

The data collection for RQ4 was guided by a media campaign conceptual model that described three categories of campaign outcomes: short-term (i.e., increased awareness, attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs); mid-term (i.e., policies, systems, or environmental strategies and individual behavior changes); and long-term (i.e., social norm and population behavior changes) [11]. Published evaluations of media campaigns identified by the scoping review process were considered as evidence to inform RQ4. Once all relevant campaigns were identified, additional Google searches were conducted using each campaign name and the terms “evaluation” and “outcome” to identify any formal evaluations that were not captured in the scoping review process. The outcomes for the international media campaigns were described only for those relevant to the U.S. context.

3. Results

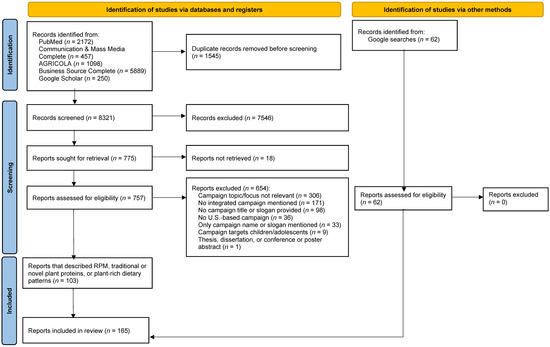

Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the scoping review of media campaigns that were used to encourage a Western diet or to support sustainable diet transitions for Americans. The scoping review identified 8321 unique records that underwent abstract screening, of which 757 full-text reports were assessed for eligibility. A total of 103 reports met the inclusion criteria that described 40 unique campaigns launched between 1917 and 2023. This included 19 campaigns that promoted RPM products in line with a Western diet (RQ1) and 21 campaigns that promoted plant-rich dietary patterns, RPM reduction or replacement, or the purchase or consumption of traditional or novel plant-based proteins (RQ2). Iterative Google searches identified an additional 62 reports that described 44 media campaigns, including 12 campaigns that promoted RPM products (RQ1) and 32 campaigns that promoted sustainable diet components in alignment with RQ2.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for sustainable diet media campaign scoping review [57].

Table 2 shows the 84 campaigns categorized into the sustainable diet media campaign typology and separated into two columns based on the campaigns’ alignment with a Western (RQ1) or sustainable diet (RQ2). Eight campaigns were international or global in nature, while the remainder were exclusively U.S.-focused. All 165 records are cited alongside the corresponding campaigns in this article, and a comprehensive list is also available in Table S2.

Table 2.

A typology of 84 media campaigns * that encouraged Western dietary principles or sustainable diet transitions.

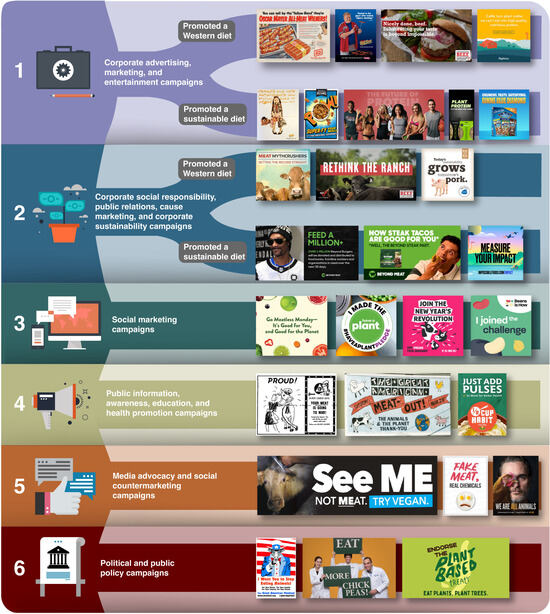

The RQ1 and RQ2 evidence identified a campaign landscape dominated by corporate advertising, marketing, and entertainment campaigns (58.6%; n = 51). The second most frequent campaign category was public information, awareness, education, and health promotion (13.8%; n = 12), followed by CSR, accountability, and corporate sustainability campaigns (12.6%; n = 11). Few media advocacy and countermarketing (5.7%; n = 5), social marketing (4.6%; n = 4), or political and public policy (4.6%; n = 4) campaigns were identified. Three campaigns fit into two separate campaign categories. The RQ1 and RQ2 findings for each of these campaign categories are described in detail in the following sections. Figure 3 provides an illustrative sample of media campaign images from each typology category. Figure S2 provides a fair use evaluation for the media campaign images allowed by the U.S. nominative fair use doctrine that protects the use of trademarked images for non-commercial educational or research purposes.

Figure 3.

Illustrative images of media campaigns that promoted a Western or sustainable diet organized by typology category.

3.1. Corporate Advertising, Marketing, and Entertainment Campaigns

Corporate advertising, marketing, and entertainment campaigns promote a specific brand or product with the intent of increasing its commercial success through sales, use, or consumption [11]. Of the 51 corporate advertising, marketing, and entertainment campaigns identified, 53% (n = 27) encouraged RPM intake as part of a Western diet, while 47% promoted traditional plant-based proteins (n = 18) or novel PBMA products (n = 6) to support a sustainable diet (Table 2).

3.1.1. Red Meat Campaigns

Of the 15 media campaigns used to promote red meat between 1976 and 2023, eight campaigns promoted beef, and seven promoted pork products. No campaigns were identified that promoted lamb. The earliest red meat campaign identified was The Iowa Chop campaign that was launched in 1976 by the Iowa Porkettes, the women’s auxiliary of the Iowa Pork Producers Association [58].

The National Pork Board was established by the U.S. Congress in 1985 to collect assessments or “fees” from pork producers per pig sold [59]. These assessments are used to administer pork research, education, and promotion programs under what is collectively called the Pork Checkoff program, with oversight from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) [60]. In 1987, the National Pork Board and the National Pork Producers Council, an industry trade association that contracts with the National Pork Board, launched the first Pork Checkoff campaign titled Pork. The Other White Meat that aimed to reposition pork as a direct competitor of lean poultry [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. In 1995, the Pork Checkoff program shifted its marketing strategy to focus on a new theme with the USD 20 million Taste What’s Next campaign [60,83,84,85,86]. This campaign retained The Other White Meat slogan [61], as did the Don’t Be Blah campaign launched in 2005 [65,66,87,88]. In 2011, the Pork Checkoff program shifted to a new USD 25 million campaign with the slogan Pork. Be Inspired [67,89,90,91]. Amidst the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the Pork Checkoff spent USD 28.88 million on domestic and international marketing to launch the Pork as a Passport campaign [92,93]. The 1998 Pork You Can Cut with a Fork campaign that promoted Hormel Foods’ Always Tender line of pork products was the only identified pork campaign that was launched by a food processing company [64,73,94].

The earliest beef campaigns were launched during the early to mid-1980s and included two campaigns (i.e., Make Ends Meat—With the Great Taste of Beef and Beef Gives Strength) funded by the National Livestock and Meat Board’s Beef Industry Council that led national beef promotion efforts prior to the development of the national Beef Checkoff program [95,96]. The national Beef Checkoff program was established by the U.S. Congress in 1985 to support beef education, research, and promotion through fees collected from beef producers per head of cattle [59,97]. The Beef Checkoff program is managed by the Cattlemen’s Beef Promotion and Research Board and the USDA [97]. The National Cattlemen’s Beef Association is an industry marketing and trade association that contracts with the Beef Checkoff program to implement campaigns and other promotional efforts [95,97].

The Beef Checkoff program has funded four campaigns since 1986 (i.e., Real Food for Real People [63,95], Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner [76,81,82,88,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116], Beef. It’s What You Want [100,101,102,103,117], and Powerful Beefskapes [118]). The Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner slogan has been used consistently over 30 years in the longest-running Beef Checkoff-funded campaign that was launched in 1992 and is still active as of March 2024 [119]. Multiple sub-campaigns have been launched under the broader Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner campaign, such as Nicely Done, Beef that positioned beef as a top protein to consumers [119]. However, for this analysis, these campaigns were considered one campaign with a unified aim of increasing beef commodity sales to U.S. distributors and retailers and increasing consumption by Americans. By 2022, the Beef Checkoff program reported USD 43.8 million in revenue and USD 42.8 million in program expenses that included the Beef. It’s What’s For Dinner campaign [97].

Of the four meatpackers that control most of the U.S. beef market, no National Beef or Cargill campaigns were identified in this campaign review. Moreover, only one beef campaign was identified for JBS USA and one for Tyson Foods. The majority of Tyson Foods campaigns encompassed their entire product line or promoted poultry products that were excluded from the search criteria and analysis. Tyson Food’s 2017 Mealtime Matters campaign was unique in its promotion of the company’s Star Ranch Angus beef brand specifically to increase retail sales nationwide [120]. In 2020, JBS launched the Beefitarian campaign, which was active as of January 2024, to bring together beef lovers [121]. While the campaign has donated beef and cash to food banks and food projects (a component of a CSR campaign) [121], this did not appear to be a primary aim of the campaign.

3.1.2. Processed Meat Campaigns

Twelve processed meat campaigns were identified that spanned from 1963 to 2019. Most processed meat campaigns (n = 7) were launched after 2000. Seven of the 12 processed meat campaigns identified were for hot dogs: four for Sara Lee’s Ball Park Franks [122,123,124,125], two for Kraft Foods’ Oscar Meyer wieners [126,127], and one for ConAgra’s Hebrew National hot dogs [128,129]. Two campaigns promoted Hormel Foods’ SPAM (not an acronym) that marketed a canned spiced ham product [130,131], while three campaigns promoted jerky products (two for the Slim Jim [132,133,134,135] and one for Jack Links [136,137]).

3.1.3. Traditional Plant-Based Protein Campaigns

The scoping review identified 18 campaigns for traditional plant-based proteins launched between 1986 and 2023, of which 16 campaigns were for peanuts or tree nuts, one for sunflower seeds [138], and one for soybeans [139]. The earliest campaign identified was the 1986 A Can A Week campaign by Blue Diamond, a cooperative of almond growers that promoted canned almonds [140]. Three campaigns were launched in 2023, including one for Blue Diamond snack almonds [141], one for Planters cashews [142], and a generic almond campaign funded by the Almond Board of California [143]. One other Blue Diamond campaign was identified [144], along with one campaign for Wonderful pistachios [145], one for Hampton Farms peanuts [146], and two for Planters peanuts [147,148,149,150].

Two campaigns (i.e., Energy for the Good Life and The Perfectly Powerful Peanut) were funded by the National Peanut Board [54,151], which collects assessments from peanut producers to fund research, education, and promotion with oversight from the USDA [152]. Another six campaigns were funded by federal marketing orders, or boards established by producers or handlers that collect industry funds to enhance the industry as the board sees fit, with approval and supervision from USDA [153]. This included one campaign funded by the American Pecan Council [154], two by the Almond Board of California [143,155], and three by the California Walnut Board [156,157,158]. One campaign was funded by the American Soybean Association [139], a policy and advocacy organization that contracted with the United Soybean Board to carry out U.S. Soybean Checkoff-supported activities [159]. The 2021 #SoyOntheGo social media campaign followed soybeans from farm to market and focused on justifying U.S. investments in infrastructure during the COVID-19 pandemic for the long-term success of the soybean industry [139].

3.1.4. Novel PBMA Product Campaigns

The novel PBMA campaigns (n = 6) included two campaigns launched in 1999, one for Worthington Foods’ Morningstar Farms brand [160,161] and one for Boca Burger [160]. Two national campaigns (i.e., The Future of Protein and Go Beyond) promoted Beyond Meat products and highlighted the benefits of plant proteins, featuring pro-athletes who fueled themselves with these products [162,163,164]. One state-specific campaign (i.e., Fall in Love with Plant Based) was launched in 2018 by the Plant Based Food Association (PBFA), a trade association representing plant-based food companies, in partnership with Lucky Supermarket locations across Northern California [165,166]. The campaign promoted a variety of plant-based products for the PBFA’s member brands, such as Beyond Meat [165,166]. The most recent campaign was Impossible Foods, Inc.’s 2021 We are Meat campaign for the Impossible Burger, which challenged the idea that meat comes only from animals through the slogan “Meat for meat lovers—made from plants” and that ran for less than a month [167,168].

3.2. Corporate Social Responsibility, Public Relations, Corporate Sustainability, and Cause Marketing Campaigns

CSR, public relations, corporate sustainability, and cause marketing campaigns—a variation of CSR—utilize media to align a company with social or sustainability causes or benefits or promote or defend a company’s work in this area to improve a company’s public reputation and protect their business practices and profits [11,169,170]. Of the 11 campaigns identified in this category, 4 campaigns supported the Western diet (Table 2). The earliest campaign identified was the Meat Mythcrushers campaign launched in 2011 by the American Meat Institute and the American Meat Science Association that aimed to “reconnect Americans to modern food production and to ‘crush’ some of the more popular myths associated today with meat and poultry” [171]. The campaign was launched in response to negative meat industry press from researcher and activist actions, such as the Meatless Monday campaign [171], with messages that largely focused on how meat had been unfairly targeted by the media and researchers and how meat could be part of a healthy and sustainable diet [172]. In 2021, the pork industry launched two campaigns that aimed to show the cleanliness and care of farmed pigs (i.e., Real Pork Mythbusting) [173,174] and pork producers’ commitments to reducing their environmental footprint (i.e., Farming Today for Tomorrow) [175]. Similarly, starting in 2017, the Beef Checkoff program shifted the focus of the longstanding Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner campaign to emphasize sustainable beef production practices [176,177]. Through sub-campaigns including Rethink the Ranch (2017) [176] and Raised and Grown (2022) [177], the campaigns utilized video, social media, and other outlets to connect consumers to beef producers and share “how beef is raised safely, humanely, and sustainably” [177].

The other seven campaigns in this category promoted plant-based products and included campaigns implemented by Morningstar Farms (n = 1), Greenleaf Foods (n = 1), Beyond Meat (n = 3), Eat the Change (n = 1), and Impossible Foods (n = 1). In 2014, Morningstar Farms launched a campaign that encouraged Americans to make small dietary changes to increase the consumption of plant foods, particularly Morningstar PBMA products, and reduce red meat intake to benefit the planet [178,179]. Greenleaf Foods’ 2020 Lightlife campaign advertised the brand’s reformulated, “clean” PBMA products [10,180,181]. The Lightlife campaign emphasized that the company was making a “clean break” from competitors like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, which they called out for using fillers, genetically modified organisms, and additives in their products [180]. As part of the 2020 Feed a Million+ cause marketing campaign, Beyond Meat worked with partners to donate and hand out more than one million Beyond Burgers and meals to food banks, hospitals, community groups, and non-profit organizations amidst the COVID-19 pandemic [182,183]. Eat the Change’s annual IncrEDIBLE Planet Challenge promoted a planet-friendly diet as part of Earth Month in April, marketing Beyond Meat and other plant-based foods as part of the pathway to change [184,185]. In 2023, Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods each launched corporate sustainability campaigns that showed the PBMA “farm to fork” production process and emphasized the smaller environmental impact of PBMA products compared to traditional meat, respectively [186,187]. A second 2023 Beyond Meat campaign titled This Changes Everything focused on the health benefits of novel PBMA products following the American Heart Association’s certification of Beyond Steak as a “heart-healthy” choice [188].

3.3. Social Marketing Campaigns

For this study, social marketing campaigns were defined as those that use commercial marketing principles and behavior change theory to mobilize individuals, communities, or population groups to start, modify, reject, or stop a behavior [11]. Campaigns included in this category were those that publicly mentioned using a behavior change theory or framework or those that described contributing to a social change movement, as social movements are often guided by social marketing tactics [189]. Four social marketing campaigns were identified that supported sustainable diets across two decades (2003–2023). No social marketing campaigns were identified that promoted the Western diet. One campaign was U.S.-focused, while three campaigns were implemented in multiple countries.

The Meatless Monday campaign was launched in 2003 by Sid Lerner and the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future in Baltimore, Maryland, and was grounded in behavior change research [190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201]. The premise for the Meatless Monday campaign, which had expanded to more than 40 countries through 2023, was that individuals were more likely to engage in healthy behaviors at the start of the week and that frequent messages might help to reinforce and drive health behavior change [202,203]. The Produce for Better Health Foundation’s 2019 Have a Plant campaign was also described as a social movement and was similarly grounded in behavior change research [204]. The Have a Plant campaign utilized the Know-Feel-Do Behavioral Framework to educate and encourage Americans to incorporate more plant foods into their diets [204].

The international Veganuary campaign was launched in the United Kingdom in 2013 and in the U.S. in 2020 [192,205,206,207,208,209,210]. This campaign used social marketing strategies to drive individual and collective behavior change [211] and aimed to foster “a global mass movement…with the aim of ending animal farming, protecting the planet, and improving human health” [212]. The international Beans is How campaign was launched in 2023 and used a theory of change approach with the aim to double global bean consumption by 2028 [213,214]. Over two decades, these social marketing campaigns have incorporated advocacy and activism into public educational efforts to encourage consumers to adopt plant-rich dietary patterns.

3.4. Public Information, Awareness, Education, and Health Promotion Campaigns

Public information, awareness, education, and health promotion campaigns are used by government agencies and civil society organizations to inform or educate individuals, communities, or populations about a health- or sustainability-related issue related to the purchase or consumption of a specific food or beverage brand or product or with the practice of a dietary behavior [11]. Twelve campaigns were identified that met this definition, all of which were intended to raise public awareness, educate, or promote sustainable diet behaviors, such as increasing the intake of pulses or reducing RPM purchase and consumption across more than a century (1917–2023). No public information campaigns were identified that promoted RPM intake as part of a Western diet. Three campaigns were international, eight were national, and one was launched in New York City (i.e., the Eat a Whole Lot More Plants campaign).

The earliest campaign identified was the Meatless Day campaign launched by the U.S. Foods Administration during World War I [191,196,215,216] that encouraged Americans to reduce their red meat intake by enacting a “Meatless Tuesday” to save these products to send to the U.S. troops fighting overseas [216]. A similar campaign called Share the Meat was launched by the U.S. Office of War Information during World War II to encourage Americans to reduce their red meat intake to conserve resources and support U.S. troops [217,218].

Between the mid-1980s and early 1990s, two campaigns (i.e., the Beyond Beef and Great American Meatout) were launched to reduce Americans’ red meat intake to support human health, the economy, the environment, and animal rights. The Great American Meatout campaign (now called Meatout) was an educational and public policy campaign that started in the U.S. and had expanded to more than 20 other countries as of 2024 [219]. The Beyond Beef campaign was launched by the Beyond Beef Coalition, an international group consisting of more than 35 environmental, animal-rights, and food-policy groups, in response to the Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner campaign [110,220,221]. The campaign urged Americans to reduce their beef intake by 50% over 10 years [110].

The 2014 Take Extinction Off Your Plate campaign by the Center for Biological Diversity educated Americans on an earth-friendly diet and encouraged a 90% reduction in beef production and consumption along with a 50% reduction of all other animal products [222]. Two campaigns educated Americans about specific sustainable dietary patterns: the New American Plate launched in 2000 [223,224] and International Mediterranean Diet Month launched in 2009 [225]. One campaign promoted the increased consumption of organic and local foods (i.e., the Cool Foods campaign launched in 2008 [226,227]), and four campaigns educated or promoted the consumption of plant foods between 2017 and 2023 (i.e., Half Cup Habit [228], Future 50 Foods [229], Anything is Pulse-able [230], and Eat a Whole Lot More Plants [231,232]).

3.5. Media Advocacy and Social Countermarketing Campaigns

Media advocacy and social countermarketing campaigns expose or challenge corporate motives or marketing practices and encourage individual or community actions to change corporate policies and practices to elicit sustainability-related benefits for people or society [11,233,234]. Such campaigns, often led by public advocacy groups and public-interest civil society groups, have been used to counter tobacco companies for decades and to counter the industry marketing of sugary beverages and other unhealthy food and beverage products [11,233].

This study’s scoping review identified five media advocacy and social countermarketing campaigns. Four campaigns were launched by the animal-rights organization People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and encouraged Americans to adopt a vegan diet. Launched between 1990 and 2023, these campaigns used graphic imagery, catchy slogans, and celebrity influencers to raise public awareness and mobilize civil action to change the meat industry’s treatment and use of animals in large-scale, industrialized agri-food systems [235,236,237,238].

In contrast, the Center for Consumer Freedom, a group funded by the meat industry and restaurant chains, launched the Clean Food Facts campaign in 2019 that used graphic imagery and catchy slogans to promote and defend Western dietary principles [239,240]. This campaign used advertisements to criticize PBMA companies for using unfamiliar ingredients and marketing highly processed products, which the campaign referred to as “fake meat”, and to encourage Americans to eat traditional RPM products [239,240].

3.6. Political and Public Policy Campaigns

Political and public policy campaigns encourage individual and community activism to promote policy changes that support or restrict food and beverage products, issues, or behaviors [11]. Four relevant campaigns were identified (1985–2021) that supported sustainable diet transitions. Since its launch in 1985, the Meatout campaign included a public policy component. The campaign encouraged citizens to request city, county, or state officials to issue a proclamation to declare March 20th as Meatout Day, a day when all residents were encouraged to eat a plant-based diet [219]. The U.S. Center for Food Safety’s Cool Foods campaign (2008) encouraged individuals, businesses, organizations, and cities to sign the Cool Foods pledge and commit to eating more local, organic foods with minimal processing or packaging and to choosing plant-based foods over animal products [226,227]. The 2016 Eat More Chickpeas campaign advocated for hospital policy changes to eliminate fast food restaurants in hospital settings and promote plant-based food intake [241,242]. An international campaign was launched in 2021 that urged individuals, businesses, organizations, and governments worldwide to endorse the negotiation of a global Plant-based Treaty [243]. This international treaty outlined actions to stop climate degradation caused by animal agriculture and shift towards plant-based diets globally [243].

3.7. U.S. Campaign Evaluations

Of the 84 campaigns identified, the Meatless Monday campaign was the only one that had a published evaluation. A 2021 nationally representative survey commissioned by the Meatless Monday campaign found that 38% of Americans had heard of the campaign, and 20% had participated in the campaign at some point [244]. Rayala et al. 2022 [199] evaluated the perceived effectiveness of Meatless Monday messages compared to control messages seen by U.S. adults (n = 1244) through an online survey. The study found that the campaign’s health and environmental messages were more effective at increasing individuals’ intentions to reduce meat consumption, a predictor of behavior change [199]. This evaluation described only short-term outcomes. Meatless Monday campaign evaluations were also conducted within specific hospitals [245] and schools [246] that were beyond the scope of this study.

4. Discussion

The scoping review findings indicate that long-running, multi-million-dollar corporate advertising and marketing campaigns have promoted RPM products to Americans for more than 50 years. Many of these campaigns have received oversight and legitimacy from U.S. government agencies, particularly the USDA, and are considered government speech [59,109]. Advertising and marketing campaigns for plant-rich commodities such as nuts, seeds, and beans were implemented concurrent to the RPM campaigns, while corporate PBMA campaigns emerged in the past decade (2010–2023). Multiple U.S. and international campaigns were identified that promoted plant-rich dietary patterns, but few utilized social or behavior change theories to guide campaign development, and only one campaign (i.e., Meatless Monday) was evaluated in the U.S. context.

4.1. Competing RPM and Plant-Based Food Advertising and Marketing Efforts

Ranganathan et al., 2016 [15] describe four strategies for shifting consumption away from animal-based proteins and towards plant-based proteins and sustainable diets that include minimizing disruption, selling a compelling benefit, maximizing awareness, and evolving social norms. While campaigns promoting plant-based products and plant-rich dietary patterns utilize these strategies, they compete against RPM campaigns that have also used these strategies for decades to influence Americans’ dietary behaviors [15]. For instance, this study observed that starting in 2021, amidst growing concern about the environmental impacts of RPM products, the Beef and Pork Checkoff programs launched corporate sustainability campaigns highlighting the sustainability practices of small- and medium-scale farmers, an example of “selling a compelling benefit”. These campaigns ran alongside PBMA campaigns that emphasized the environmental and health benefits of PBMA products compared to their RPM counterparts, which may have confused U.S. consumers. This is relevant because, in 2023, more than 50% of U.S. consumers reported being highly concerned about sustainability, and one in ten consumers said they would pay more for a sustainable product [247].

An estimated 800 times more U.S. public spending is used to support animal-sourced foods and beverages compared to PBMAs and other alternative proteins each year [248]. Likewise, animal-sourced lobbying groups spend 40 times more than PBMA firms on lobbying efforts, including informing U.S. dietary guidance [248]. To the authors’ knowledge, no study has analyzed how funding differences between RPM and PBMA sectors may impact media campaigns’ effectiveness at influencing consumer awareness, perceptions, or dietary behaviors. Sexton et al. 2019 [249] described the narratives used by PBMA and other alternative protein companies in media and marketing efforts. These narratives have characterized PBMA products as the solution to global livestock production issues and promise a better future food system [249]. These authors also identified three counter-narratives (i.e., “not a serious threat”, “not real food”, and “not legally defined”) that the livestock industry has used in campaigns and other media efforts to downplay and question the role of PBMA products in current and future food systems [249]. Since 2020, U.S. consumer interest in and consumption of PBMA products has increased, but many consumers also increased their red meat intake in this period, indicating that PBMA products may be consumed in addition to rather than in place of RPM products [17]. Plant-based food companies have discussed developing a marketing coalition similar to the U.S. Checkoff programs [250]. This coalition, which would launch as early as 2024, would enable plant-based food companies to develop and implement coordinated national marketing campaigns to promote the commodities in this sector [250]. Ongoing funding disparities will likely continue to challenge the PBMA marketing efforts in a sector dominated by RPM advertising, marketing, and corporate sustainability campaigns.

Nearly one-third of U.S. government farm subsidies support beef, pork, and other livestock and the production of commodity crops (e.g., corn and soybeans) used for livestock feed [251]. An estimated 13% of farm subsidies support food grains used for human consumption, while only 4% are for fruits and vegetables and 2% for nuts and seeds [251]. The USDA should adopt expert recommendations to review the Checkoff programs’ effectiveness and limitations and identify marketing strategies that better support plant-based food products and the DGA-recommended Healthy Vegetarian pattern that supports human and planetary health [252]. This action was recommended by the Task Force on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health in the report drafted to inform the 2022 White House Conference On Hunger, Nutrition, and Health [252] that led to the Biden-Harris Administration National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health [253]. This aligns with global climate scientists’ recommendations for national governments to align agricultural subsidies with the Paris Agreement and other global climate goals and for high-income countries to transition to more plant-based food systems to support planetary health [5]. Given that Americans’ RPM intake exceeds current DGA recommendations [24], which are co-developed by the USDA and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as evidence-based nutrition advice, the USDA’s support for meat commodities and marketing campaigns could be viewed as a conflict of interest. These efforts to further increase Americans’ intake of RPM products undermine policy coherence from other major U.S. government initiatives, such as those outlined in the 2022 Biden-Harris National Strategy, that aim to create healthier food environments and reduce diet-related chronic diseases [253]. The USDA leadership should consider re-prioritizing and increasing funding to support plant-based food Checkoff promotion and marketing efforts for traditional plant-based proteins.

4.2. Misinformation Concerns Related to Media Campaigns

Civil society groups and the media have accused multiple corporate sustainability and countermarketing campaigns and funders identified through this scoping review of using misinformation and greenwashing tactics to promote RPM purchase and consumption and discourage PBMA consumption [9,240,254,255]. Misinformation refers to the use of false or misleading information to influence individuals’ perceptions, beliefs, or behaviors [254]. Greenwashing is a subcategory of misinformation that promotes false or overstated information about the environmental benefits of a product, service, or brand that cannot be substantiated by fact-based evidence [9]. A 2023 Guardian article called out the Beef Checkoff program for such tactics in the Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner campaign that downplayed the environmental impacts of large-scale industrialized beef production [255]. The 2019 Center for Consumer Freedom’s Clean Food Facts campaign has been accused of using misinformation tactics that attacked PBMA products’ contribution to health with ad slogans like “Fake Meat or Dog Food?” and “Should Fake Meat Have a Cancer Warning?” [240,254]. Similarly, Tyson Foods and JBS USA have both been accused of misleading U.S. customers with environmental sustainability claims about their beef products [9,256]. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission, Food and Drug Administration, and the USDA should collaborate to provide regulatory oversight of the use of misinformation in media campaigns, particularly among Checkoff-funded campaigns that are considered government speech.

4.3. Government and Civil Society Campaigns Used to Promote Sustainable Diet Transitions

Public health media campaigns led by government or civil society groups can be effective strategies to help change individual- and population-level diet- and nutrition-related behaviors and social norms [12,257]. Transnational food and beverage companies that have multi-million and multi-billion-dollar annual marketing budgets dominate the traditional and digital media landscapes and influence popular culture [258], making it challenging for the public health community to compete to raise consumers’ awareness and influence food and beverage purchase and consumption behaviors. Most government- or civil society-supported campaigns identified in this study that promoted PBMA products and plant-rich diets focused on raising awareness and educating Americans about plant-based products or plant-rich dietary patterns. Only four social marketing campaigns were identified that were grounded in behavior change or social change theory to influence consumer dietary behaviors and change social norms.

Information and education campaigns have been used to shift a variety of U.S. consumers’ diet- and health-related behaviors. While necessary, information and education alone are insufficient to encourage sustained diet-related behavior changes [14,15]. Rust et al., 2020 [22] described a conceptual framework for designing interventions to reduce red meat intake that ranged from eliminating choice (e.g., meat-free days), which is restrictive and controversial but more effective, to providing information (e.g., awareness-raising campaigns), which is less effective but more accepted by the public. Findings from the Meatless Monday campaign indicate that more restrictive campaigns can influence individuals’ intentions to change short-term behaviors [199]. However, given the lack of formal evaluations of information and awareness-raising campaigns, such as Take Extinction Off Your Plate and Meatout, that did not report using behavior change theory, one cannot compare their effectiveness at encouraging sustainable diet transitions.

Only four distinct political or public policy campaigns were identified, which suggests that supporters of sustainable diets have focused campaign messages primarily on changing individual cognitive and behavioral outcomes rather than promoting government policy and corporate practice changes. These findings align with a 2013 study of non-governmental organizations’ actions to reduce meat consumption in the U.S., Canada, and Sweden that found that few organizations promoted national-level policies to reduce meat intake [226]. Policy inertia and polarization surrounding this issue have contributed to the lack of civil-society organizations that have adopted campaigns to encourage individual or policy-level RPM reduction [259]. Polarization in the U.S. Congress is likely to impede federal policy initiatives to reduce RPM consumption [260].

Media campaigns that use strategic communications are a promising strategy to promote individual, institutional, and community behavior change and to support local and state policy changes [260]. Future civil society, business, and government-funded campaigns should be rigorously evaluated to determine their capacity and effectiveness to change behaviors and drive social norm changes for a sustainable diet transition. Media campaigns are one of many interventions that could be used to encourage Americans to transition to sustainable diets [22] and should be used in conjunction with other efforts to encourage behavior change and improve the enabling environment for consumers to transition to sustainable diets.

4.4. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

A strength of this study was the use of a systematic scoping review process to identify published literature on media campaigns over more than a century. Additionally, the use of gray literature and U.S. media sources to identify campaigns that were not yet discussed in traditional published literature sources enabled greater consideration of potential media campaigns for inclusion. This review is historical in nature but offers key insights into the changes in campaign types and products promoted across more than a century. Despite efforts to be comprehensive and exhaustive in the review process, there was no way to ensure that the authors identified all relevant media campaigns. Researcher subjectivity may have played a role in determining whether campaigns met the inclusion criteria, although the researchers attempted to mitigate this by utilizing two independent reviewers. Since this review used digital databases and resources to identify campaigns, print-only campaigns, particularly those that pre-dated the Internet, may have been missed. A further limitation is that the sources used in this study were restricted to those available in the English language.

Individuals and populations in the U.S. and globally restrict or exclude red meat or follow plant-rich dietary patterns for a variety of reasons beyond health or sustainability concerns, such as religious, moral, or spiritual beliefs that are often tied to animal rights [40]. While this scoping review did not exclude these reasons, the analysis of media campaigns may not have identified the breadth of informal campaigns from religious entities or other groups that are likely not as readily shared through traditional or digital media sources reviewed for this study.

Future research should measure the effectiveness of the media campaigns identified through this scoping review in changing individual and community behaviors and influencing policy or social norms changes. In the absence of campaign evaluations, campaign images, slogans, and messages could be tested with target U.S. audiences to assess their perceived message effectiveness, as was performed with the Meatless Monday campaign [199]. Future research could analyze non-U.S.-based evaluations for international or global sustainable diet campaigns, such as Veganuary and Meatless Monday, to assess the available data on their effectiveness in diverse country contexts. Additional research is also needed on how U.S. and international food retailers use media marketing and campaigns to influence consumers’ knowledge, interest, and behaviors related to transitioning to sustainable diets, as point-of-purchase promotional efforts were not a focus of this study.

Future research could also use existing RPM and alternative protein message framing typologies [249,261] to explore how the messages in these campaigns are framed to American consumers and the impact of competing narratives on consumer behaviors. This could fill a gap in research on how conflicting media marketing messages influence consumers’ sustainability and health behaviors. These additional research efforts could inform the development of future media campaigns to promote plant-based products and sustainable diets both in the U.S. and internationally.

This scoping review study could be replicated to identify and categorize the landscape of RPM, plant-based protein, and sustainable diet campaigns in other countries to inform individual- and population-level behavior, policy, and social norm changes. Categorizing evaluation data from such efforts in other countries could be useful for identifying the campaign narratives and messages that effectively influence short- or long-term cognitive or behavioral changes, which could be replicated or adapted for the U.S. context.

Future research should also assess the extent to which misinformation is present within U.S.-focused RPM campaign narratives and whether PBMA campaigns utilize misinformation to promote the sustainability benefits of their products or to counter narratives about RPM products. Analyzing the media discourse around RPM in the U.S. can help identify the narratives used to increase consumption and develop positive counter-narratives to support RPM reduction and replacement efforts. Given the increasingly global reach of media and marketing efforts through social media and other digital outlets, analyzing the U.S. sustainable diet campaign discourse can also inform advocacy and education efforts to encourage sustainable diet transitions in other country settings.

5. Conclusions

Industry has been promoting the purchase and consumption of RPM products to Americans through well-funded advertising, marketing, CSR, and corporate sustainability campaigns for more than 60 years, many of which are supported by the U.S. government. While traditional plant-based protein campaigns have been implemented for decades, novel PBMA product campaigns have emerged over the past decade in the U.S. These traditional and novel plant-based protein campaigns must compete in a market dominated by RPM investment and marketing.

Many U.S.-focused and international public information and education campaigns and a handful of social marketing campaigns promoted plant-rich dietary patterns to Americans. Research indicates that media campaigns are a promising outlet through which to encourage individual and population-level behavior, policy, or social norms changes. However, outcome data are insufficient to show a measurable effect of plant-based protein and plant-rich diet campaigns on influencing individual or community knowledge or behaviors or on driving long-term policy or social norm changes. Future plant-based protein and plant-rich diet campaigns should use behavior change theory and social change principles and be rigorously evaluated to demonstrate how media campaigns may support sustainable diet transitions. Greater action is needed to restrict and regulate the use of misleading or deceptive media campaign messages that foster misinformation, to prioritize support for plant-based proteins and plant-rich dietary patterns, and to evaluate the impact of media campaigns that support a sustainable diet transition for Americans.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16114457/s1, Figure S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist for the systematic scoping review of sustainable diet media campaigns; Figure S2: Fair use evaluation for sustainable diet media campaign images; Table S1: Detailed search terms and strategy for the systematic scoping review of sustainable diet media campaigns; Table S2: Evidence sources collected from the systematic scoping review of sustainable diet media campaigns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C.S. and V.I.K.; methodology, K.C.S.; formal analysis, K.C.S., N.L. and V.I.K.; data curation, K.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C.S.; writing—review and editing, K.C.S., N.L., A.H., V.E.H., E.L.S. and V.I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was partially supported by the Virginia Tech Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project VA-160189. E.L.S. was partially supported by Virginia Cooperative Extension’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed), with funding from the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service in partnership with the Virginia Department of Social Services. Funding for open access publication for this article was provided by the Virginia Cooperative Extension Family Nutrition Program and the Virginia Tech Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The supplemental evidence used in Tables S1 and S2 are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Virginia Tech’s research librarians for guidance in designing and implementing the search strategy for this systematic scoping review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change. Climate Change and Land: IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. Recommendations and Public Health and Policy Implications 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Recommendations.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Rose, D.; Heller, M.C.; Roberto, C.A. Position of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior: The importance of including environmental sustainability in dietary guidance. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 3–15.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwatt, H.; Hayek, M.N.; Behrens, P.; Ripple, W.J. Options For A Paris-Compliant Livestock Sector. Brooks McCormick Jr Animal Law & Policy Program, Harvard Law School. Published March 2024. Available online: https://animal.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/Paris-compliant-livestock-report.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Grimmelt, A.; Moulton, J.; Pandya, C.; Snezhkova, N. Hungry and confused: The winding road to conscious eating. McKinsey & Company. 5 October 2022. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/hungry-and-confused-the-winding-road-to-conscious-eating (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Food Insight. 2023 Food & Health Survey. International Food Information Council. 23 May 2023. Available online: https://foodinsight.org/2023-food-and-health-survey/ (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Cargill. Research Finds More Consumers Weighing Sustainability Claims on Packaged Food Choices. 3 February 2022. Available online: https://www.cargill.com/2022/research-finds-more-consumers-weighing-sustainability-claims#:~:text=The%20proprietary%20research%20finds%2055,fielded%20this%20research%20in%202019 (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Changing Markets Foundation. Feeding Us Greenwash: An Analysis of Misleading Claims in the Food Sector. March 2023. Available online: https://changingmarkets.org/report/feeding-us-greenwash-an-analysis-of-misleading-claims-in-the-food-sector/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Kraak, V.I. Perspective: Unpacking the wicked challenges for alternative proteins in the United States: Can highly processed plant-based and cell-cultured food and beverage products support healthy and sustainable diets and food systems? Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraak, V.I.; Consavage Stanley, K. A Systematic scoping review of media campaigns to develop a typology to evaluate their collective impact on promoting healthy hydration behaviors and reducing sugary beverage health risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy-Nichols, J.; Marten, R.; Crosbie, E.; Moodie, R. The public health playbook: Ideas for challenging the corporate playbook. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1067–e1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraak, V.I.; Consavage Stanley, K.; Harrigan, P.B.; Zhou, M. How have media campaigns been used to promote and discourage healthy and unhealthy beverages in the United States? A systematic scoping review to inform future research to reduce sugary beverage health risks. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan, J.; Vennard, D.; Waite, R.; Dumas, P.; Lipinski, B.; Searchinger, T. Shifting Diets for a Sustainable Food Future. World Resources Institute. April 2016. Available online: https://www.wri.org/research/shifting-diets-sustainable-food-future (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Sustainable Healthy Diets: Guiding Principles; World Health Organization; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United States: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516648 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Consavage Stanley, K.; Hedrick, V.E.; Serrano, E.; Holz, A.; Kraak, V.I. US adults’ perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors towards plant-rich dietary patterns and practices: International Food Information Council Food and Health survey insights, 2012–2022. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025, 9th ed.; December 2020. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global impacts of western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: A narrative review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuenschwander, M.; Stadelmaier, J.; Eble, J.; Grummich, K.; Szczerba, E.; Kiesswetter, E.; Schlesinger, S.; Schwingshackl, L. Substitution of animal-based with plant-based foods on cardiometabolic health and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Mulders, M.D.G.H.; Mouritzen, S.L.T. Outside-in and bottom-up: Using sustainability transitions to understand the development phases of mainstreaming plant-based in the food sector in a meat and dairy focused economy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2023, 197, 122906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, N.A.; Ridding, L.; Ward, C.; Clark, B.; Kehoe, L.; Dora, M.; Whittingham, M.J.; McGowan, P.; Chaudhary, A.; Reynolds, C.J.; et al. How to transition to reduced-meat diets that benefit people and the planet. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinnari, M.; Vinnari, E. A framework for sustainability transition: The case of plant-based diets. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics. 2014, 27, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R.; Henderson, A.D.; Phelps, A.; Janda, K.M.; van den Berg, A.E. Five U.S. dietary patterns and their relationship to land use, water use, and greenhouse gas emissions: Implications for future food security. Nutrients 2023, 15, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Cattle & Beef: Sector at a Glance. Updated 30 August 2023. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/animal-products/cattle-beef/sector-at-a-glance/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Buchholz, K. The biggest producers of beef in the world. Statista. 27 April 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/19127/biggest-producers-of-beef/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Kraak, V.I.; Consavage Stanley, K.; Rincón-Gallardo Patiño, S.; Houghtaling, B.; Shanks, C.B. How the G20 leaders could transform nutrition by updating and harmonizing food-based dietary guidelines. UNNJ 2022, 1, 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard, T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Plate and the Planet. n.d. Available online: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/sustainability/plate-and-planet/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Qian, F.; Riddle, M.C.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Hu, F.B. Red and processed meats and health risks: How strong is the evidence? Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Sharma, P.; Shu, S.; Lin, T.-S.; Ciais, P.; Tubiello, F.N.; Smith, P.; Campbell, N.; Jain, A.K. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Feng, K.; Baiocchi, G.; Sun, L.; Hubacek, K. Shifts towards healthy diets in the US can reduce environmental impacts but would be unaffordable for poorer minorities. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M. Environmental impacts of food production. Our World in Data. 2022. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Santo, R.E.; Kim, B.F.; Goldman, S.E.; Dutkiewicz, J.; Biehl, E.M.B.; Bloem, M.W.; Neff, R.A.; Nachman, K.E. Considering plant-based meat substitutes and cell-based meats: A public health and food systems perspective. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W.; Thomas, L.F.; Coyne, L.; Rushton, J. Review: Mitigating the risks posed by intensification in livestock production: The examples of antimicrobial resistance and zoonoses. Animal 2021, 15, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werthman, C. The meat industry is advertising like big oil. DeSmog. 18 April 2023. Available online: https://www.desmog.com/2023/04/18/meat-industry-advertising-big-oil-climate-change-ncba-nppc-checkoff/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Mock, S. Meat wars: Why Biden wants to break up the powerful US beef industry. The Guardian. 25 August 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/aug/25/meat-wars-why-biden-wants-to-break-up-the-powerful-us-beef-industry#:~:text=A%20recent%20executive%20action%20signed,price%20of%20beef%20has%20risen%E2%80%9D (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Coyne, A. Eyeing alternatives—Meat companies with stakes in meat-free and cell- based meat. JustFood. 13 July 2023. Available online: https://www.just-food.com/features/eyeing-alternatives-meat-companies-with-stakes-in-meat-free-and-cell-based-meat/?cf-view (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Bushnell, C.; Specht, L.; Almy, J. 2022 State of the Industry Report: Plant-Based Meat, Seafood, Eggs, and Dairy. Good Food Institute. 2023. Available online: https://gfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2022-Plant-Based-State-of-the-Industry-Report.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Leitzmann, C. Vegetarian nutrition: Past, present, future. Amer. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 496S–502S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B.; Otis, B.O.; McCarthy, G. Can plant-based meat alternatives be part of a healthy and sustainable diet? JAMA 2019, 322, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, R.; Lim, A.J.; Forde, C.G. A critical appraisal of the evidence supporting consumer motivations for alternative proteins. Foods 2020, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, C.J. Plant-based animal product alternatives are healthier and more environmentally sustainable than animal products. Future Foods 2022, 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.; Moses, R.; Sammons, N.; Birkved, M. Potential to curb the environmental burdens of American beef consumption using a novel plant-based beef substitute. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozicka, M.; Havlík, P.; Valin, H.; Wollenberg, E.; Deppermann, A.; Leclère, D.; Lauri, P.; Moses, R.; Boere, E.; Frank, S.; et al. Feeding climate and biodiversity goals with novel plant-based meat and milk alternatives. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polaris Market Research. Plant-Based Meat Market Share, Size, Trends, Industry Analysis Report, 2022–2030. August 2023. Available online: https://www.polarismarketresearch.com/industry-analysis/plant-based-meat-market (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Davenport, D. What Is Integrated Marketing Communication (IMC)? Purdue University. n.d. Available online: https://online.purdue.edu/blog/communication/what-is-integrated-marketing-communication-imc (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Juska, J.M. Pathways for brand messages and content. In Integrated Marketing Communication: Advertising and Promotion in a Digital World, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant Based Foods Association. 2022 U.S. Retail Sales Data for the Plant-Based Foods Industry. n.d. Available online: https://plantbasedfoods.org/2022-retail-sales-data-plant-based-food (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- World Health Organization. Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the Consumption of Red Meat and Processed Meat. 26 October 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/cancer-carcinogenicity-of-the-consumption-of-red-meat-and-processed-meat (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Englund, T.R.; Zhou, M.; Hedrick, V.E.; Kraak, V.I. How branded marketing and media campaigns can support a healthy diet and food well-being for americans: Evidence for 13 campaigns in the United States. J. Nutr. Educat. Behav. 2020, 52, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C. Burger wars: How Burger King’s rivalry with McDonald’s reverberates through adland. Marketing Dive. 17 May 2022. Available online: https://www.marketingdive.com/news/mcdonalds-burger-king-brand-rivalry-burger-wars/621713/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Covidence. Better Systematic Review Management. n.d. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, J.B. “Hop to the Top with the Iowa Chop”: The Iowa Porkettes and cultivating agrarian feminisms in the Midwest, 1964–1992. Agric. Hist. 2009, 83, 477–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, P.E. Federal communication about obesity in the Dietary Guidelines and checkoff programs. Obesity 2006, 14, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]