Risk Preferences and Entrepreneurial Decision-Making: Evidence from Experimental Methods in Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Design and Methods

3.1. The Model

3.2. The Experiments

- You have a fixed-wage job of VND 8,000,000 per month. You will earn a total of VND 96,000,000 in a year.

- You decide to invest VND 100,000,000 to start a new business. If you succeed, you will earn VND 300,000,000 per year (when using the 50/50 chance, we need to have the reward of VND 300,000,000 per year in order to ensure that both options A and B offer similar expected values). Otherwise, you will lose all if the business fails. The probability is 50/50 (The decision to use 50/50 probability in this study aims to simulate real-world investment uncertainty while ensuring experimental control and replicability. This probability reflects the unpredictable nature of entrepreneurships and simplifies the decision-making process for participants, making the experiment clearer and more accessible. By maintaining a consistent probability distribution, this study enhances the robustness and reliability of empirical research, allowing for easier replication and validation of findings. Despite real-world variations, 50/50 probability provides a practical framework for examining the relationship between risk preferences and entrepreneurial behavior).

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

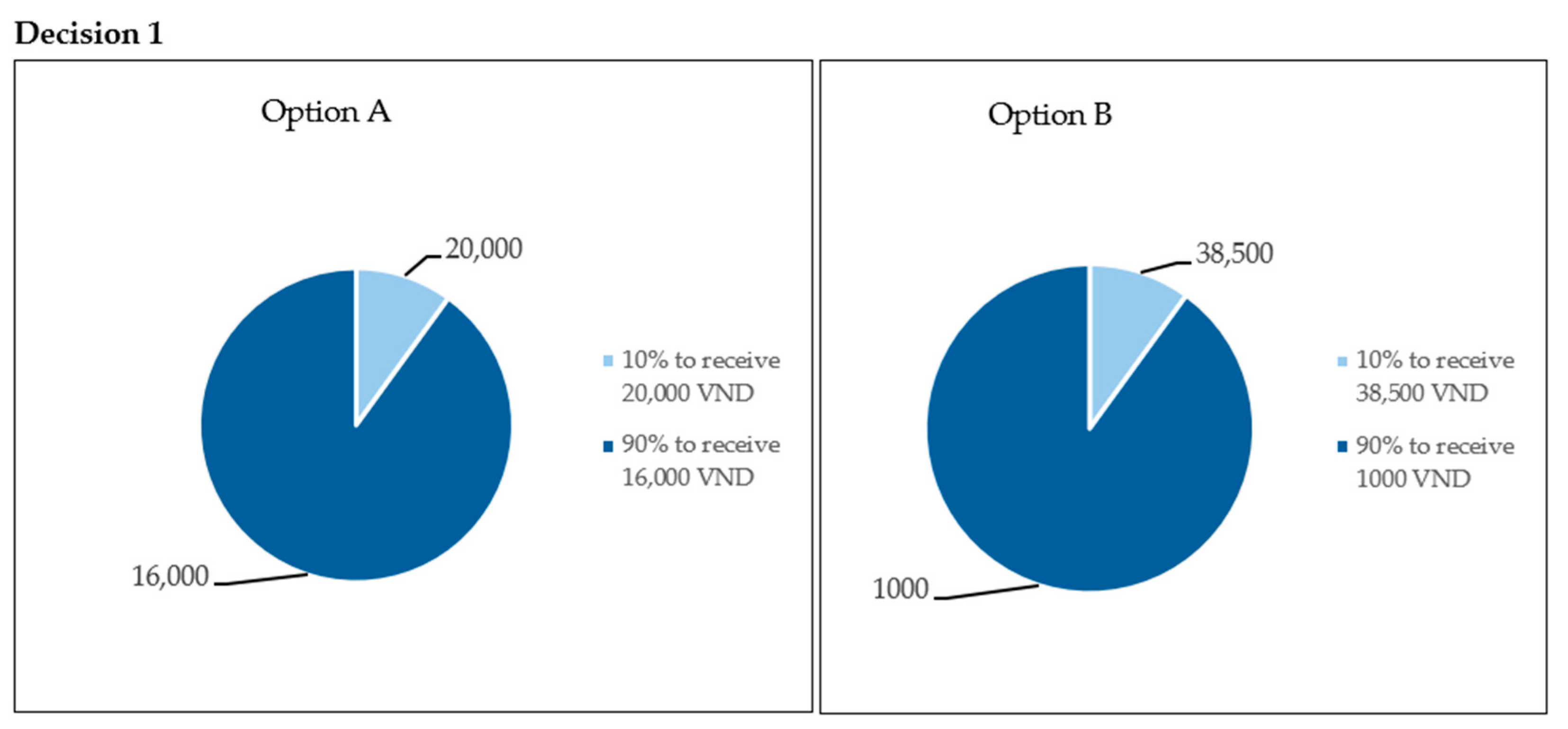

Appendix A. Example of a Visual Aid for the Multiple Price List’s Decision Task

Appendix B. Survey Questions Related to Variables in the Model

References

- Hsu, D.K.; Burmeister-Lamp, K.; Simmons, S.A.; Foo, M.D.; Hong, M.C.; Pipes, J.D. “I know I can, but I don’t fit”: Perceived fit, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, A.; Cordova, A.; Gambardella, A. A Scientific Approach to Entrepreneurial Decision-Making: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial. Manag. Sci. 2017, 66, 564–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomy, S.; Pardede, E. An entrepreneurial intention model focussing on higher education. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1423–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A.; Unel, B. Do attitudes toward risk taking affect entrepreneurship? Evidence from second-generation Americans. J. Econ. Growth 2021, 26, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Blasio, G.; De Paola, M.; Poy, S.; Scoppa, V. Massive earthquakes, risk aversion, and entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 295–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilevbare, F.M.; Ilevbare, O.E.; Adelowo, C.M.; Oshorenua, F.P. Social support and risk-taking propensity as predictors of entrepreneurial intention among undergraduates in Nigeria. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 16, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, S.; Auburger, J.; Paleczek, D. The why and the how: A nexus on how opportunity, risk and personality affect entrepreneurial intention. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 2656–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Williams, T.A.; Patzelt, H. Thinking About Entrepreneurial Decision Making: Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 11–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Wach, K.; Schaefer, R. Perceived public support and entrepreneurship attitudes: A little reciprocity can go a long way! J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 121, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ahlstrom, D. Risk-taking in entrepreneurial decision-making: A dynamic model of venture decision. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 37, 899–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluku, M.M.; Nansubuga, F.; Otto, K.; Horn, L. Risk Aversion, Entrepreneurial Attitudes, Intention and Entry among Young People in Uganda and Germany: A Gendered Analysis. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 7, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, J.A.; Antoncic, B.; Gantar, M.; Hisrich, R.D.; Marks, L.J.; Bachkirov, A.A.; Li, Z.; Polzin, P.; Borges, J.L.; Coelho, A.; et al. Risk-taking propensity and entrepreneurship: The role of power distance. J. Enterprising Cult. 2018, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, D. An experimental analysis of risk and entrepreneurial attitudes of university students in the USA and Brazil. J. Int. Entrep. 2015, 13, 370–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamböck, C.; Hopp, C.; Keles, C.; Vetschera, R. Risk aversion in Entrepreneurship Panels: Measurement Problems and Alternative Explanations. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2017, 38, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.; Berry, G.R. Characteristics, traits, and attitudes in entrepreneurial decision-making: Current research and future directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 1965–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T. Attitudes toward risk and self-employment of young workers. Labour Econ. 2010, 17, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, F.M.; König, J.; Schröder, C. Risk preference and entrepreneurial investment at the top of the wealth distribution. Empir. Econ. 2024, 66, 735–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U.; Imas, A. Experimental methods: Eliciting risk preferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2013, 87, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.S.; Hartog, J.; Jonker, N.; Van Praag, C.M. Low risk aversion encourages the choice for entrepreneurship: An empirical test of a truism. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2002, 48, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, S.M. Impatience, Information and Risk Taking in a General Equilibrium Model of Occupational Choice. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1979, 46, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlstrom, R.E.; Laffont, J.J. A general equilibrium entrepreneurial theory of firm formation based on risk aversion. J. Political Econ. 1979, 87, 719–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaaramo, M.; Ala-Mursula, L.; Miettunen, J.; Korhonen, M. Economic preferences and temperament traits among business leaders and paid employees. Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 60, 1197–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honjo, Y.; Ikeuchi, K.; Nakamura, H. Does risk aversion affect individuals’ interests and actions in angel investing? Empirical evidence from Japan. Jpn. World Econ. 2024, 70, 101253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Khattak, M.S.; Anwar, M. Personality traits and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of risk aversion. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachert, M.; Hyll, W.; Sadrieh, A. Entry into self-employment and individuals’ risk-taking propensities. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 1057–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhou, G. Is risk aversion related to occupational choice: Evidence from 1996 PSID. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Cain, K.W. Reassessing the link between risk aversion and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of the determinants of planned behavior. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 793–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brañas-Garza, P.; Estepa-Mohedano, L.; Jorrat, D.; Orozco, V.; Rascón-Ramírez, E. To pay or not to pay: Measuring risk preferences in lab and field. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2021, 16, 1290–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.; Habib, S.; James, D.; Williams, B. Varieties of risk preference elicitation. Games Econ. Behav. 2022, 133, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasoff, J.; Zhang, W. The performance of time-preference and risk-preference measures in surveys. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 1149–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackethal, A.; Kirchler, M.; Laudenbach, C.; Razen, M.; Weber, A. On the role of monetary incentives in risk preference elicitation experiments. J. Risk Uncertain. 2023, 66, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elston, J.A.; Harrison, G.W.; Rutström, E.E. Experimental Economics, Entrepreneurs and the Entry Decision; University of Central Florida Working Paper; University of Central Florida: Orlando, FL, USA, 2006; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- MacKo, A.; Tyszka, T. Entrepreneurship and risk taking. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 58, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, S.; Schade, C.; Mußhoff, O.; Odening, M. Holding on for too long? An experimental study on inertia in entrepreneurs’ and non-entrepreneurs’ disinvestment choices. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2010, 76, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister-Lamp, K.; Lévesque, M.; Schade, C. Are entrepreneurs influenced by risk attitude, regulatory focus or both? An experiment on entrepreneurs’ time allocation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 456–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudstaal, M.; Sloof, R.; Van Praag, M. Risk, uncertainty and entrepreneurship: Evidence from a lab-in-the-field experiment. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 2897–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Meier, F.; Niemand, T. Experimental methods in entrepreneurship research: The status quo. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 958–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.W.; Wood, M.S.; Mitchell, J.R.; Urbig, D. Applying experimental methods to advance entrepreneurship research: On the need for and publication of experiments. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U. Portfolio choice and risk attitudes: An experiment. Econ. Inq. 2010, 48, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.K.; Simmons, S.A.; Wieland, A.M. Designing entrepreneurship experiments: A review, typology, and research agenda. Organ. Res. Methods 2017, 20, 379–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meoli, A.; Fini, R.; Sobrero, M.; Wiklund, J. How entrepreneurial intentions influence entrepreneurial career choices: The moderating influence of social context. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaref, J.; Brodmann, S.; Premand, P. The medium-term impact of entrepreneurship education on labor market outcomes: Experimental evidence from university graduates in Tunisia. Labour Econ. 2020, 62, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, C.A.; Vergara, M. Risk aversion, downside risk aversion, and the transition to entrepreneurship. Theory Decis. 2021, 91, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, A.Z.M. Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity: Evidence from matrilineal and patriarchal societies. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.A.; Laury, S.K. Risk aversion and incentive effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, K. Risk aversion and incentive effects (by Charles Holt and Susan Laury). In The Art of Experimental Economics; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 162–175. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, T.; Gassmann, X.; Faure, C.; Schleich, J. Individual characteristics associated with risk and time preferences: A multi country representative survey. J. Risk Uncertain. 2023, 66, 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estelami, H. The effects of need for cognition, gender, risk preferences and marketing education on entrepreneurial intentions. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2020, 22, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elston, J.A.; Audretsch, D.B. Financing the entrepreneurial decision: An empirical approach using experimental data on risk attitudes. Small Bus. Econ. 2011, 36, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | |

| Entrepreneurial decision | 1 = start a business; 0 = choose a fixed-wage job |

| Entrepreneurial participation | 1 = individually or jointly own a business; 0 = other |

| Risk preferences | |

| Safe choices | Risk classification based on the number of safe choices in the MPL risk game |

| Risk averse | 1 = risk-averse; 0 = risk-taking or risk-neutral |

| Risk invest | The amount of money that participants invested in the first round of the entrepreneurial investment game |

| Other variables | |

| Gender | 1 = male; 0 = female |

| Opportunity recognition | 1 = recognition of any opportunity for starting a new business; 0 = none |

| Self-efficacy | 1 = have knowledge and skills to start a business (self-assessment); 0 = none |

| Business training | 1 = attend any business course; 0 = none |

| Family background | 1 = family member engaged in self-employment; 0 = none |

| Decision No. | Option A | Option B | Expected Payoff Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10% to receive VND 20,000 and 90% to receive VND 16,000 | 10% to receive VND 38,500 and 90% to receive VND 1000 | VND 11,650 |

| 2 | 20% to receive VND 20,000 and 80% to receive VND 16,000 | 20% to receive VND 38,500 and 80% to receive VND 1000 | VND 8300 |

| 3 | 30% to receive VND 20,000 and 70% to receive VND 16,000 | 30% to receive VND 38,500 and 70% to receive VND 1000 | VND 4950 |

| 4 | 40% to receive VND 20,000 and 60% to receive VND 16,000 | 40% to receive VND 38,500 and 60% to receive VND 1000 | VND 1600 |

| 5 | 50% to receive VND 20,000 and 50% to receive VND 16,000 | 50% to receive VND 38,500 and 50% to receive VND 1000 | VND −1750 |

| 6 | 60% to receive VND 20,000 and 40% to receive VND 16,000 | 60% to receive VND 38,500 and 40% to receive VND 1000 | VND −5100 |

| 7 | 70% to receive VND 20,000 and 30% to receive VND 16,000 | 70% to receive VND 38,500 and 30% to receive VND 1000 | VND −8450 |

| 8 | 80% to receive VND 20,000 and 20% to receive VND 16,000 | 80% to receive VND 38,500 and 20% to receive VND 1000 | VND −11,800 |

| 9 | 90% to receive VND 20,000 and 10% to receive VND 16,000 | 90% to receive VND 38,500 and 10% to receive VND 1000 | VND −15,150 |

| 10 | 100% to receive VND 20,000 | 100% to receive VND 38,500 | VND −18,500 |

| Number of Safe Choices | Range of Relative Risk Aversion | Risk Preferences Classification | Percentage of Choices in Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | r < −0.95 | Highly risk loving | 5.12 |

| 2 | −0.95 < r < −0.49 | Very risk loving | 8.37 |

| 3 | −0.49 < r < −0.15 | Risk loving | 14.88 |

| 4 | −0.15 < r < 0.15 | Risk neutral | 20.93 |

| 5 | 0.15 < r < 0.41 | Slightly risk averse | 19.53 |

| 6 | 0.41 < r < 0.68 | Risk averse | 14.88 |

| 7 | 0.68 < r < 0.97 | Very risk averse | 10.23 |

| 8 | 0.97 < r < 1.37 | Highly risk averse | 3.26 |

| 9–10 | 1.37 < r | Stay in bed | 2.79 |

| Variables | Mean | Std.Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | ||||

| Entrepreneurial decision | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Entrepreneurial participation | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 |

| Risk preferences | ||||

| Safe choices | 4.6 | 1.87 | 1 | 9 |

| Risk averse | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Risk invest | 54.6 | 18.92 | 20 | 100 |

| Other variables | ||||

| Gender | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Opportunity recognition | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Business training | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Family background | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Entrepreneurial decision | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2 | Entrepreneurial participation | 0.21 * | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3 | Risk averse | −0.18 * | −0.13 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4 | Safe choices | −0.21 * | −0.13 | 0.81 * | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5 | Risk invest | 0.16 * | −0.00 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 1.00 | |||||

| 6 | Gender | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.00 | 0.09 | 1.00 | ||||

| 7 | Opportunity recognition | 0.19 * | 0.28 * | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||

| 8 | Self-efficacy | 0.20 * | 0.23 * | −0.05 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.27 * | 1.00 | ||

| 9 | Business training | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |

| 10 | Family background | 0.06 | 0.09 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1.00 |

| Entrepreneurial Decision | Entrepreneurial Participation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Safe choices | −0.056 *** (0.019) | −0.029 * (0.017) | ||||

| Risk averse | −0.189 *** (0.069) | −0.132 ** (0.065) | ||||

| Risk invest | 0.004 ** (0.002) | −0.000 (0.002) | ||||

| Gender | −0.062 (0.079) | −0.079 (0.078) | −0.083 (0.079) | −0.133 ** 0.066) | −0.143 ** (0.065) | −0.133 ** (0.066) |

| Opportunity recognition | 0.150 ** (0.073) | 0.153 *** (0.073) | 0.143 ** (0.073) | 0.215 *** (0.068) | 0.221 *** (0.068) | 0.214 *** (0.067) |

| Self-efficacy | 0.159 ** (0.073) | 0.178 *** (0.072) | 0.184 *** (0.072) | 0.173 *** (0.066) | 0.183 ** (0.065) | 0.189 *** (0.064) |

| Business training | 0.024 (0.097) | 0.012 (0.096) | −0.010 (0.095) | 0.120 (0.094) | 0.111 (0.093) | 0.107 (0.092) |

| Family background | 0.057 (0.079) | 0.038 (0.080) | 0.054 (0.079) | 0.068 (0.071) | 0.056 (0.072) | 0.073 (0.070) |

| Goodness-of-fit test after logistic model | ||||||

| Pearson chi2 | 83.68 | 35.80 | 122.36 | 110.41 | 42.19 | 111.56 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.768 | 0.571 | 0.237 | 0.118 | 0.294 | 0.494 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tran, T.T.; Pham, N.K. Risk Preferences and Entrepreneurial Decision-Making: Evidence from Experimental Methods in Vietnam. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4392. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114392

Tran TT, Pham NK. Risk Preferences and Entrepreneurial Decision-Making: Evidence from Experimental Methods in Vietnam. Sustainability. 2024; 16(11):4392. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114392

Chicago/Turabian StyleTran, Truc Thanh, and Nam Khanh Pham. 2024. "Risk Preferences and Entrepreneurial Decision-Making: Evidence from Experimental Methods in Vietnam" Sustainability 16, no. 11: 4392. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114392

APA StyleTran, T. T., & Pham, N. K. (2024). Risk Preferences and Entrepreneurial Decision-Making: Evidence from Experimental Methods in Vietnam. Sustainability, 16(11), 4392. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114392