1. Introduction

Urban and regional planning, an interdisciplinary field focused on applying knowledge to real-world situations, plays a role in addressing the challenges of climate change [

1]. The fields of disaster management and planning are increasingly recognizing the distinct challenges faced by rural communities—defined by the U.S. Census as geographies having a population less than 1000 persons per square mile [

2]. While urban centers often dominate the discourse on disaster recovery and planning, researchers have been turning their interests toward rural communities in the path of powerful and frequent hurricane events such as those in Asia (e.g., Philippines, Bangladesh, and Vietnam) [

3], along the Gulf Coast of the United States (e.g., Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama) [

4], in the Caribbean (e.g., Haiti and Puerto Rico) [

5,

6], and in Central America (e.g., Honduras, Nicaragua, and Belize) [

7]. Filling this gap is significant because rural areas have unique experiences when dealing with disasters that set them apart from urban regions [

4,

8].

Rural communities across the world are not only characterized by limited resources and infrastructure [

2] but they also have a higher level of risk associated with sustainability challenges, be it social, ecological, or economic [

9,

10]. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that rural communities are often overshadowed in recovery and response strategies, leading to inadequate attention and support during critical times of need [

11]. This systemic oversight in disaster response magnifies the risks for these communities and hinders their path to resilience and sustainability.

This article seeks to delve deeper into the realms of disaster recovery and thus future resiliency and sustainability in rural areas. This study is driven by the following questions: (1) What obstacles hinder disaster recovery efforts in rural settings? (2) How can these communities try to improve their future resilience and sustainability? To tackle these questions, 18 interviews with professionals (e.g., government organizations, emergency responders, non-profit organizations, and community leaders in community-based organizations) involved in rural recovery in Puerto Rico were conducted in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, which devastated the island in 2017.

The present study addresses a research gap by investigating how rural areas handle and bounce back from disasters within the U.S. National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF). This study is also more concerned with long-term sustainability and resilience rather than solely focusing on the immediate response, which is understudied in rural areas. In other words, while short-term factors are about immediate survival and stabilization after an emergency, long-term factors focus on sustainable recovery, resilience building, and improved readiness for future incidents. Through examining the viewpoints of community-based organizations (CBOs), the present study uncovers perspectives from the grassroots that are often overlooked in higher-level planning and policymaking. This study provides perspectives on tailoring disaster response and resilience tactics for rural areas, highlighting the significance of avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach.

This article tells a story starting with the vulnerabilities of rural regions during disasters and delves into the efforts needed across various sectors (e.g., government, non-profit, etc.) for effective recovery and future resilience building. The participants shared existing barriers to increasing resilience, such as the lack of data integration, issues concerning financial resources, and capacity building, that uniquely impact rural areas. The interviewees examined the recovery process, emphasizing the necessity of multi-sector responses and underscoring the significance of coordination and collaboration, as evidenced by their experiences following Hurricane Maria. Overall, this study provides recommendations to tailor strategies to rural contexts that involve the community and develop policies to enhance long-term sustainability and resilience in dealing with future disasters.

2. Literature Review

In crafting this literature review, a meticulous and multifaceted strategy has been employed. It initiates with an exploration spanning disciplines to encompass the wide-ranging knowledge related to disaster recovery and resilience in rural settings. This review investigates studies that identify existing vulnerabilities specific to rural communities which are often exacerbated following disasters. Emphasis is placed on understanding the differing impacts of events compared to scenarios, thus underscoring the distinctive nature of challenges faced by rural areas.

The subsequent phase of the review strategy entailed examining disaster circumstances, infrastructure breakdowns and aid distribution, with a particular focus on elucidating the compounded vulnerabilities present in rural regions. The literature was scrutinized for case studies and research results that outline both the enduring effects of disasters as well as efforts aimed at enhancing resilience that have been implemented or are necessary.

Disaster recovery and resilience have historically been focused on urban areas. The literature extensively covers the challenges faced by cities in terms of social vulnerability issues and infrastructure damage post-disaster. However, there is a lack of exploration into the struggles of rural communities, which often deal with issues like isolation and limited access to services. This literature review summarizes some of the challenges identified in some of the studies that have addressed issues in rural communities while pinpointing gaps in disaster recovery research related to rural areas.

This study is guided by two research questions arising from the gaps identified in the existing literature: (1) What specific obstacles hinder disaster recovery efforts in regions? (2) How can these communities improve their resilience and sustainability moving forward? By addressing these questions, this article seeks to shed light on the complexities of disaster recovery and contribute to an understanding of resilience that can inform tailored strategies for rural communities. I explore a range of research disciplines to create a summary that not only highlights familiar obstacles that other researchers have identified but also sheds light on the overlooked difficulties and resilience of rural areas when dealing with disasters.

2.1. Pre-Existing and Post-Disaster Conditions in Rural Areas

Understanding the differential impact of disasters on rural versus urban communities is essential yet understudied. This gap in knowledge is particularly acute concerning the pre-existing vulnerabilities that amplify the effects of disasters in rural areas. Studies consistently underscore how in post-disasters, existing vulnerabilities are exacerbated [

12]. This means that areas with a higher proportion of marginalized groups—older adults, children, immigrants, women, disabled individuals, lower-income individuals, etc.—confront more hurdles during disasters [

13,

14]. For instance, in urban areas, disadvantaged communities, most often those belonging to minority groups, bear a higher impact due to pre-existing issues related to poor-quality housing or education [

15,

16]. But which pre-existing conditions do rural communities experience compared to urban areas?

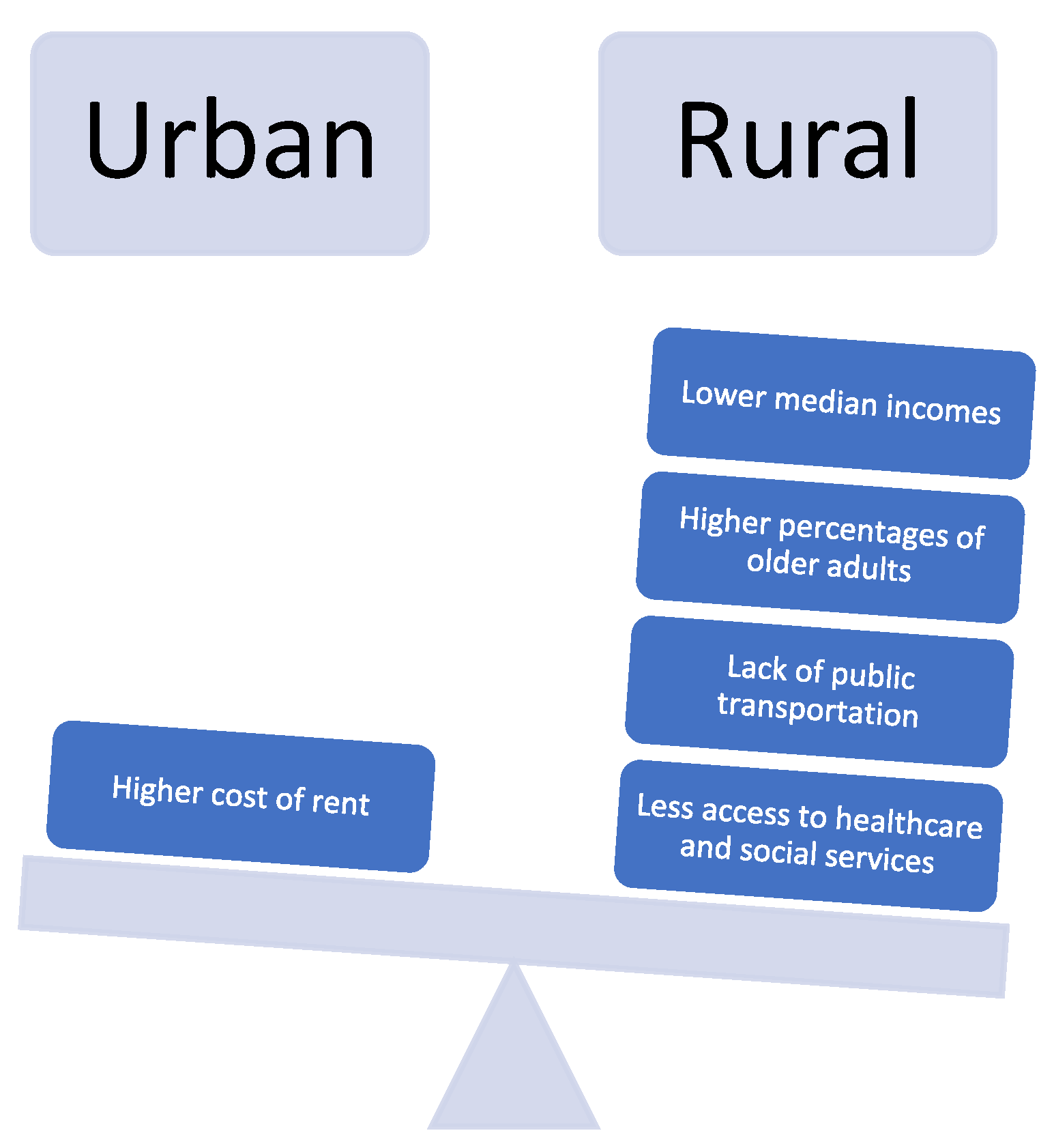

Figure 1 shows some of the pre-existing vulnerability conditions unique to rural areas. While urban areas have a higher cost of living, which can disproportionately affect low-income individuals, they also tend to offer more job opportunities, including higher-paying jobs [

17]. Thus, the median income in rural communities tends to be lower than in urban areas [

18]. Rural areas tend to have higher percentages of older adults (aged 65+), as younger populations may move to urban areas for employment [

19]. Access to healthcare and services can be limited, affecting the quality of life for older residents [

20]. Rural communities often lack specialized services and facilities for people with disabilities or people with mental health issues [

21]. Transportation in rural communities can be a significant issue for those who do not own cars, as public transportation options are often limited [

22]. These factors create unique post-disaster challenges in rural areas that are not sufficiently addressed in the existing disaster management literature.

Based on the pre-existing vulnerability conditions, rural areas can experience unique challenges after disasters (

Figure 2). Post-disaster, the vulnerability of rural areas is often compounded by infrastructure collapse that could leave them unreachable as often some communities have access to one road, one bridge, etc. Due to transportation obstacles, the aftermath of Hurricane Maria underscored disparities in the distribution of aid (e.g., food, water, medicine, etc.) in rural areas. Rural areas usually have less robust electrical and communication networks which face longer overloads or disruptions [

23]. Furthermore, the limited channels for information dissemination exacerbate coordination challenges in emergency responses [

24]. Finally, rural communities after disasters receive limited media attention, delayed assistance, less financial assistance, and increased outmigration.

2.2. Building Disaster Resilience in Rural Communities

Building disaster resilience refers to the ability to recover from a disaster and return to a state of normalcy or a new normal, including restoring services and livelihoods [

25,

26]. At least conceptually we could expect that within the context of this study, disaster resilience could be achieved by (1) developing and implementing disaster management plans [

27], (2) investing in robust infrastructure that can withstand disaster impacts [

28], (3) fostering community engagement and participation in disaster preparedness [

29], (4) promoting funding mechanisms for disaster response and recovery [

30], and (5) encouraging partnerships among the government, private sector, and civil society for resource sharing and collaboration [

31].

A multi-sectoral approach is necessary for effectively addressing the unique needs of rural disaster recovery [

8]. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector play roles in scenarios where government reach may be limited [

32]. Working together across sectors and collaborating with communities is vital to dealing with the process of recovery in rural regions [

8].

While cities demonstrate a quicker rebound post-disaster, rural areas lag behind, hampered by geographic constraints, transportation issues, and financial limitations. The case studies from Hurricane Maria recovery efforts in rural settings like Florida, Puerto Rico, and North Carolina show the distinct obstacles in implementing recovery support [

33].

It is crucial to understand where local resources for funding come from and to empower communities to participate in recovery efforts [

34]. García et al., using a case study of rural communities in Florida, Puerto Rico, and North Carolina, also identified various obstacles in implementing measures for supporting communities after a disaster, including geographical constraints, transportation limitations, financial issues, and community engagement difficulties.

Building resilience in rural areas faces obstacles from policy frameworks that do not cater adequately to rural needs in integrating data for efficient planning [

33]. Issues like access to training also pose challenges [

9]. Community engagement is a theme in the literature that emphasizes the importance of communication and transparency for successful recovery endeavors [

29,

35]. Those who are most familiar with the issues are best suited to devise solutions, highlighting the value of community knowledge and engagement [

12,

36,

37].

Ensuring long-term resilience involves developing tailored solutions that consider the social, economic, and environmental characteristics of rural areas [

38]. By empowering communities through participation and innovative initiatives, resilience can be greatly improved [

39]. Research and policymaking play a role in shaping strategies to tackle the obstacles faced by these communities [

40].

One crucial aspect of the emergency response system involves the National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF) which serves as a manual that facilitates assistance for states, tribes, territories, and local areas impacted by disasters [

41]. The framework allows emergency managers to collaborate and work together cohesively. The NDRF defines the responsibilities of individuals, communities, state and local governments, federal agencies, and other stakeholders involved in the recovery efforts. Recovery Support Functions (RSFs) are organized groups of entities specializing in areas such as housing, healthcare, and social service economic revival, infrastructure system maintenance, natural resource preservation, cultural heritage protection, community planning initiatives, and capacity building. Recommendations for advance disaster recovery planning and coordination strategies include stakeholder engagement methods and integration with emergency response frameworks. The framework ensures that the recovery process prioritizes community engagement by interacting with residents to address their needs effectively while leveraging insights and resources. It aims to meet the recovery requirements of every community with an emphasis on building a resilient and sustainable long term recovery plan.

The research in this field has pointed out a gap in our knowledge regarding how rural communities within the U.S. NDRF respond to and recover from disasters. While the existing literature focuses on examples and case studies from around the world, there is a lack of information about the challenges faced by rural areas within U.S. territories (e.g., Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana) when it comes to dealing with disasters. This is important because rural regions have different experiences compared to urban areas, especially concerning resource distribution, media coverage, and the speed and effectiveness of recovery efforts.

This study addresses this research gap by examining the hurdles encountered by rural communities within the U.S. NDRF during disaster recovery, with an examination of the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. By focusing on the hurdle’s that rural communities within the U.S. NDRF face, this study offers a novel examination of disaster recovery that extends beyond immediate response to consider long-term resilience and sustainability. Through this exploration, the present study links its findings with opportunities to adjust disaster planning strategies to better cater to the needs of rural regions and bolster their resilience.

3. Theoretical Framework

The examination of disaster resilience and recovery in rural areas relies on various fundamental theoretical frameworks that shape our comprehension and actions in the face of natural calamities. This section delves into these theoretical frameworks to lay the groundwork for exploring the challenges and responses witnessed in rural communities, with a particular focus on resilience theory and the idea of sustainable development.

3.1. Resilience Theory

Resilience theory is pivotal in understanding disaster recovery efforts. Resilience is defined as the ability of a system, community, or society exposed to hazards to adapt by either withstanding or undergoing change to achieve and sustain a level of functioning and organization [

42,

43,

44]. It hinges on how a social system can organize itself to enhance its capacity for learning from disasters for more effective future protection and risk mitigation measures.

Applying resilience theory in managing disasters entails examining the absorptive and transformative capacities that rural communities activate when responding to crises [

45]. Previous research has underscored the faceted nature of resilience by indicating that economic development, social connections, information dissemination networks, and community skills play crucial roles in bolstering the resilience of rural regions or small communities [

2].

3.2. Sustainability and Rural Development Theories

Connecting resilience to development in rural settings expands the conversation to encompass the merging of economic, social, and environmental objectives outlined in the Brundtland Report (1987) [

46]. This viewpoint emphasizes the importance of disaster recovery strategies that go beyond restoring what was lost and also focus on enhancing conditions post-disaster by incorporating sustainability into the recovery process [

47].

Additionally, the rural development theory offers a framework for examining how regions often facing resource constraints and heightened disaster vulnerability can strive toward development that harmonizes needs with ecological and economic sustainability [

48]. The interaction between vulnerability and development policies calls for an exploration of the policies and practices that can either impede or support resilience and sustainable recovery efforts.

3.3. Connecting Theories to Rural Disaster Recovery

This literature review reveals a gap in the application of these frameworks to real-world situations, particularly within rural environments. While urban disaster recovery has been extensively researched, rural communities encounter challenges that are not fully addressed by disaster management methods [

12].

Limited access to resources, isolation, economic limitations, and inadequate infrastructure can worsen the impact of disasters—making recovery efforts more challenging [

49]. Research conducted by Cutter et al. (2016) [

50] demonstrates that combining resilience and rural development theories can provide perspectives for designing disaster recovery plans tailored to areas’ unique needs and circumstances [

42]. By taking an approach that incorporates insights from various fields related to emergency management, sustainability studies, urban planning, etc., scholars can better navigate the intricate dynamics of disaster management in rural environments.

This theoretical framework lays the foundation for exploration by emphasizing the importance of research that connects resilience theory, development principles, and the rural development theory within the realm of disaster recovery. The subsequent sections will delve into how these theoretical frameworks manifest in the experiences of communities in Puerto Rico post-Hurricane Maria, critically evaluating practices while proposing a framework for enhancing disaster resilience and sustainable recovery in rural communities.

4. Case Study Background

The impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico was devastating and unprecedented in its magnitude. The hurricane approached the Caribbean Island on 20 September 2017 as a high-end category 4 hurricane with winds reaching up to 155 miles per hour (250 km/h) [

51]. All 3.4 million residents, the entire population of Puerto Rico, lost power [

52]. It took about one year before the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority confirmed that power had been restored to all customers, though some rural areas still faced not having service for a longer period [

53].

With no electricity, water treatment plants could not operate, leaving many, especially in rural areas, without drinking water [

54]. The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency reports indicated that about half of the population experienced water shortages at some point post-hurricane [

53]. This shortage persisted for days and weeks, so residents sought water from streams or other unsafe sources, leading to cases of leptospirosis [

55].

The delivery of food and supplies was hindered by infrastructure damage and logistical hurdles [

53]. According to a FEMA report (2018), despite tons of aid being sent to Puerto Rico, much of it remained stuck in ports and warehouses due to blocked roads in rural communities which disrupted supply chains. The initial official report stated that there were 64 deaths [

53]. Further investigations revealed a higher number, estimated to be between 3000 and 4600 fatalities caused by the hurricane’s aftermath [

53]. Most of these deaths were linked to the lack of medical assistance for people who were chronically ill (e.g., diabetic, dialysis patients, etc.) [

56]. The lack of medical care was exacerbated by the lack of electricity, clean water, and transportation obstructions [

57,

58].

Hurricane Maria resulted in losses ranging from USD 90 billion to over USD 100 billion, affecting industries like agriculture, tourism, and manufacturing [

53]. The hurricane left hundreds of thousands of houses damaged or destroyed, with roof damage leading to a large-scale displacement of residents [

59]. Those most affected were living in informal housing—which constitutes the majority in rural areas [

60,

61]. The slow recovery process recognized by FEMA exposed Puerto Rico’s infrastructure vulnerabilities and lack of preparedness for disaster events—especially in rural areas already facing resource shortages [

53]. Where the government, including those involved in emergency response, were not able to respond quickly enough, community leaders from community-based organizations and non-profits, especially small ones, were able to fill in this gap [

30,

62,

63,

64]. This case study background provides context on Hurricane Maria’s enduring devastation in Puerto Rico, and it emphasizes the need for planning focused on resilience and support systems, especially for rural communities when facing natural disasters.

The interviewees come from four different communities in Puerto Rico which is in the Caribbean: Ponce, Mayagüez, Comerío, and San Germán (

Figure 3). In 2021, the demographics of these four Puerto Rican municipalities presented varied socioeconomic conditions (

Table 1). Ponce and Mayagüez had the largest populations of 226,358 and 98,768, respectively. Comerío was the smallest municipality in the sample, with 18,990 people, followed by San Germán, with 31,879 residents. Median ages ranged from 41.1 in Comerío to 45.4 in San Germán. Poverty levels were high across the board, exceeding 49%, with Comerío facing the highest rate at 53.8%. Median income was the lowest in Comerío at USD 14,666, while Ponce had the highest at USD 18,439. In comparison, for Puerto Rico, 6.4% of the 3.2 million total population lives in rural areas. The median age was 43.1 and poverty levels were lower, at 42.7%, with a median income of USD 21,967.

5. Case Study Selection

There are various units of analysis related to case study research. The hurricane itself is a unit of analysis as a natural disaster event affecting Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico serves as another unit of analysis, providing a broader context of how such events are managed within a U.S. territory. Finally, the municipalities of Ponce, Mayagüez, Comerío, and San Germán are also examined to gain insights into local responses and impacts. By analyzing these interconnected units, from a macro to a micro perspective, this study aims to provide an understanding of disaster impacts and responses across social and geographical contexts—offering valuable data for enhancing disaster recovery strategies at all levels.

Puerto Rico was selected as a case study because of the unprecedented scale of devastation, highlighting the challenges that rural communities face during disasters. Even though the disaster was not typical because of its severity, the case study was chosen because it can illustrate the broader challenges faced by rural communities in disaster scenarios. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the severity and the frequency of hurricanes are expected to increase, which justifies the emphasis on worse-case scenarios [

64].

In addition, within the U.S. NDRF, the case study looks at a U.S. territory which provides an essential contribution to understanding disaster management in urban regions that are challenged geographically and socioeconomically marginalized. Extreme cases can be very insightful because they magnify the dynamics present in more ‘normal’ cases and can expose systemic vulnerabilities and strengths more clearly. Studying such an extreme case provides a stress test for disaster management systems, offering critical insights into the limits of current strategies and highlighting areas where improvements are essential for resilience building in rural areas, which often bear a disproportionate share of disaster impacts due to pre-existing vulnerabilities.

The four towns chosen for this study—Ponce, Mayagüez, Comerío, and San Germán—represent a range of conditions that mirror the diversity found throughout Puerto Rico. These communities showcase a range of settings like the percentage of rurality, income, and poverty rates, providing a diverse view of the island’s socioeconomic environment. Representative case studies allow for the findings from a case study to be more easily generalized to a broader population, making the insights and conclusions drawn from the study potentially applicable to similar contexts or populations. To find participants, it also helped that the author had personal ties in Ponce, Comerío, and San Germán, making it easier to find interviewees. Together, these communities serve as a microcosm for examining how natural disasters impact Puerto Rico, offering insights representative of the entire island’s population.

In terms of generalizability, while the findings are rooted in the Puerto Rican context, they offer valuable implications for rural disaster management elsewhere. The systemic challenges observed—infrastructure fragility, resource allocation, and community engagement—are relevant issues that many rural areas worldwide confront in disaster situations. By analyzing these challenges within the microcosm of Puerto Rico, this study aims to contribute to the global discourse on rural resilience, offering strategies that may be adapted and applied to similar rural settings internationally.

6. Methods: Exploring Disaster Recovery and Sustainability in Rural Communities

Figure 4 serves as a visual guide of the study design, highlighting the alignment between the research questions, the stakeholder interviews, and the coding strategy that underpins the thematic analysis. Driven by the need to comprehend and alleviate the difficulties encountered by rural areas in the aftermath of disasters, this investigation puts forth two main questions: (1) What obstacles hinder disaster recovery efforts in rural settings? (2) How can these communities try to improve their future resilience and sustainability?

To address these research questions, the author carried out 18 interviews in the spring and summer of 2023 with individuals who had firsthand experience with disaster impact and recovery. The present study employed purposive snowball sampling, which, while non-probable, was strategic in including a cross-section of different stakeholders involved in disaster recovery (the government, emergency management, NGOs, and CBOs) within the selected communities. This process helps in capturing a wide range of perspectives on disaster resilience and recovery. Talking to people from different sectors also helped with the triangulation of the data, meaning that the method helped in confirming the reliability of the information collected and reduced the likelihood of bias [

65].

I started with a list of 1–3 people who matched the selection criteria and who I knew in Comerío, Ponce, and San Germán and built the list by asking participants about people they recommended to participate in the study. In Mayaguez, I did not have any contacts, so I walked into a neighborhood where I had contacts and asked residents to refer me to people who they knew according to the pre-selected categories. The author tried to avoid potential biases by actively working to broaden the participant base and cross-verifying information across multiple sources. In addition, to further diminish biases, the author employed reflexive practices such as taking fieldnotes and debriefing after an interview as well as memoing while coding.

Table 2 shows the demographic breakdown of the participants. Half of the participants (50%) were women, a little over a third (39%) were men, and a smaller proportion (11%) identified as non-binary. The median age of the participants was 46 years old, meaning that half of the participants were younger than 46 and half were older. A small minority of the participants (11%) were non-Hispanic White, while the vast majority (89%) were Hispanic/Latino. On average, the participants have been in their current roles for 19 years, with a range spanning from 1 to 35 years, indicating a wide range of experience levels. The participants held various roles, with the largest group being community leaders in community-based organizations (CBOs) (33%), followed by non-profit organization (NGO) staff (28%), government employees (GOV) (22%), and emergency responders (ERs) (16%). Although the author did not ask about their income and educational attainment, those working in the government, NGOs, and emergency response had at least a bachelor’s degree—as a degree is required for employment. But those who lead CBOs seemed to be mixed between having a bachelor’s degree and not having one.

The interviews concentrated on examining the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in rural communities in Puerto Rico in the towns of Comerío, Ponce, San Germán, and Mayagüez. The interview guide enabled participants to narrate their experiences and reflections on challenges confronted during disaster response activities as well as the approaches they utilized or observed to reconstruct resilience. Some examples of questions in the interview guide included the following: (1) Can you describe the main challenges rural communities faced before and after Hurricane Maria? (2) In your opinion, what are the key elements of an effective disaster response for rural communities? (3) How rural communities can become more resilient in the future?

The interviews were conducted in Spanish and lasted anywhere from 20 min to 1 h, with an average of about 45 min. Fake names were given to participants to protect their identity and an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was sought to ensure the protection of human subjects. The interviews were conducted in person and audio-recorded, then transcribed using Sonix.ai and cleaned-up manually. Only quotes used in the manuscript were translated from Spanish to English. Before the coding began, the researcher immersed herself in the data, reading and re-reading the interview transcripts to become more familiar with the content. Then, initial descriptive codes were created by identifying significant or interesting features in the data using Dedoose v. 8.3.17—a software application used for analyzing qualitative research data.

Parent and child codes were used [

66]. Parent codes are broad, high-level themes or categories that can encompass a wide range of data. They are the main categories under which data are organized. These themes included “Vulnerability Risks”, “Empowering Rural Response”, “Barriers to Effective Response”, and “Strategies for Disaster Resilience and Sustainability”. Child codes are subcategories or specific aspects of the parent code. They allow for a more detailed analysis and fine-grained categorization within the broader parent theme. For “Vulnerability Risks”, these include “Pre-existing Conditions” and “Post-disaster Conditions”, highlighting factors that either existed prior to or were exacerbated by disasters. “Empowering Rural Response” features child codes like “Multisectoral Approach” and “Coordination and Collaboration”, emphasizing the need for inclusive and cooperative strategies. “Barriers to Effective Response” covers issues like the “One-size-fits-all Approach”, “Lack of Capacity Building”, and “Lack of Data”, which are challenges that hinder efficient disaster response. Lastly, “Strategies for Disaster Resilience and Sustainability” includes child codes such as “Community-centered Solutions”, “Engagement and Empowerment”, and “Policy and Research Advancement”, focusing on long-term measures for managing disasters effectively. A summary of the research questions, subject positionality of the interviewees by sector, and coding details is presented in

Table 3.

Some of the limitations of this study include the sample size as it may not fully represent all viewpoints in Puerto Rico. Relying on any self-reported data could introduce biases. To help with this issue, the researcher focused on municipalities as well as informants from a variety sectors. In addition, the researcher has her own biases as well. The researcher used standardized protocols for data collection and analysis to minimize the introduction of subjective bias. Despite these constraints, this study makes contributions to our knowledge of disaster recovery in rural areas, with potential implications for broader use.

7. Findings: Overcoming Challenges to Build Disaster Resilience

Table 3 serves to clearly outline areas of agreement and contention among the participants regarding key aspects of disaster resilience and recovery, noting that while some topics like pre-existing vulnerabilities and the need for community engagement saw general agreement, others, such as the specifics of effective response and resilience strategies, were more contested.

7.1. Vulnerability Risks

The participants acknowledged that disasters amplify existing vulnerabilities. Julia (woman, age 47, 12 years, Hispanic, NGO, and Comerío) highlighted that “We can identify those most affected post-disaster; disadvantaged communities of color and resource limited areas that face challenges, in housing, food, healthcare, education, and more during regular times”. This viewpoint resonated unanimously with all participants, underscoring the notion that those at-risk face heightened vulnerability during disasters. Juan (man, age 46, 10 years, Hispanic, CBO, and Mayagüez) mentioned that “disasters often worsen the disparities in society. The most affected are people in low-income rural areas with disabilities, like older adults, who struggle to recover”. Adding to the discussion, Ariel (non-binary, age 26, 1 year, Hispanic, CBO, and Ponce) emphasized the “increased vulnerabilities faced by groups such as older adults and individuals with chronic health conditions during disasters. Their lack of resources and limited access to support services specially in they live in rural communities make them more at risk”. Susana (woman, age 49, 20 years, Hispanic, CBO, and San Germán) expressed that “Aid could not get fast enough to rural areas because of all the debris, roads were closed for days or weeks. We were basically trapped, that was at the very beginning. Then it was no water for three months and no electricity for about a year”. Gerardo (man, age 43, 8 years, Hispanic, GOV, and Comerío) said that “We had to go to San Juan to the Capitol to protest that almost a year later we still did not have electricity. Is like the media, the government, everyone forgot about the rural areas. We stopped getting assistance, even when we needed it”. Miriam (woman, age 39, 10 years, Hispanic, GOV, and San Germán) said that “We were already dealing with population loss, but after the hurricane with schools closed for months, families started to leave. Kids from the U.S. also took their elderly parents with them to Florida or other places in the U.S. because otherwise their elderly parents would have died here with no way to store insulin or getting an oxygen tank”.

The participants emphasized how disasters worsen existing inequalities. Rural communities, often consisting of older adults and lower-income individuals, face multiple obstacles in terms of housing, healthcare, and service access. Importantly, disasters contribute to widening these gaps, particularly affecting older adults with disabilities or health issues in rural areas. Moreover, the long-term effects of a disaster can also be observed through a decrease in population as families or older adults move to improve their living conditions.

7.2. Barriers to Effective Response

During the discussion, the participants pointed out obstacles in improving disaster response and enhancing resilience. These challenges encompass issues like “Policy being national or local, people need to know that no one fits all. You cannot treat urban areas like rural areas. But unfortunately, the federal government tends to treat all areas like they all the same. Let alone thinking about the differences between Puerto Rico and states in the U.S. Mainland”, according to Gamaliel (man, age 59, 25 years, Hispanic, NGO, and Ponce). Amadis (non-binary, age 36, 9 years, Hispanic, and CBO) pointed out that what we need is more “data to have more knowledge and we need to build robust databases to have information integration. In Puerto Rico the data is here and there, and it is a mess, we need a single place or a couple places for the community to have the data they need to do their planning”. Jessica (woman, age 42, 7 years, Hispanic, NGO, and Comerío) expressed that the main issue is that “We do not know how to finance things, we do not have that capacity, the federal government should do more training on this. The other thing is most trainings are going to be in the metro area, closer to San Juan, but we are on the middle of the mountainous area. It takes a while for us to come here for training. So, we need more training but more accessible as well and not everyone is able to use Zoom either”. We must develop disaster response strategies that cater to the needs of rural regions instead of adopting a one-size-fits-all approach. Special attention was given to establishing data systems to enhance preparedness and reaction efforts in Puerto Rico. Moreover, there was an acknowledgment of the importance of financial management education, advocating community-based training opportunities.

7.3. Empowering Rural Response

Responding to disasters requires collaboration across sectors, with participation from regional, national, and international entities. Tom (man, age 62, 35 years, non-Hispanic White, ER, and Ponce) pointed out the nature of disaster response by mentioning that “it involves sectors operating at different levels”. He underscored the significance of providing support and enhancing capabilities. Reflecting on Hurricane Maria, he highlighted that there are “challenges such as socioeconomic factors, transportation constraints, and power issues that contributed to an uneven response in rural and underserved areas”. Miriam, a local government woman from San Germán, stated that “Effective disaster response involves a strategy that unites different actors like nonprofit groups, businesses, and residents. Working together is crucial for tackling the range of challenges that emerge in the wake of a catastrophe in rural areas as well as their long-term sustainability”.

Tito (man, age 40, 5 years, Hispanic, NGO, and Mayagüez) highlighted the significance of “grasping how people obtain goods and where things come from, specially to and from rural areas”, emphasizing the importance of empowering individuals and learning from real-life cases about where rural areas obtain their goods and services. Beatriz (woman, age 37, 6 years, Hispanic, CBO, and Ponce) said that “Collaboration on a scale is crucial when it comes to addressing emergencies that transcend municipalities and impact whole nations like Hurricane Puerto Rico not only urban areas or rural areas were affected but the whole Island suffered. By joining forces pooling resources and knowledge we could amplify our efforts and aid those requiring aid. What happen also in Puerto Rico is that the urban areas did recover much faster, but then they forgot about the rural areas. They stopped extending help to others once their issues were solved”.

Engaging with the community was emphasized as an important aspect. Carlos (man, age 44, 13 years, Hispanic, NGO, and Ponce) discussed developing a “community engagement structure to foster enhanced comprehension and effective recovery”. The belief that “those who are intimately familiar with the challenges are also best positioned to find solutions” resonated throughout conversations. Roberto (man, age 41, 6 years, Hispanic, NGO, and San Germán) concurred that “Poor communication and engagement. The local, state, and federal government needs to be able to communicate information effectively and be transparent as well. Communicate often and early that should be the motto”.

The participants emphasized how disaster response requires coordination. The challenges faced can be influenced by factors like socioeconomics, transportation, and infrastructure limitations. Effective strategies need to involve all sectors to handle the process of disaster recovery and promote sustainable rebuilding efforts. Effective disaster response requires coordination among a variety of sectors, especially in handling logistics for supplies to rural areas. Drawing insights from real-case studies is key to grasping how resources move and empowering communities as they gain this knowledge. Though urban regions may bounce back faster, it is crucial to sustain assistance to rural communities. Community engagement was highlighted as a factor in disaster recovery, focusing on creating frameworks for improved comprehension and recuperation along with stressing the importance of efficient, clear, and timely communication across various sectors.

7.4. Strategies for Disaster Resilience and Sustainability

The participants put forward some suggestions for long-term resilience and sustainability. Taylor (woman, age 38, 3 years, non-Hispanic White, ER, and Mayagüez) highlighted the importance of “creating solutions that are tailored to contexts and rooted in community needs and realities”. Amadis (non-binary, age 36, 9 years, Hispanic, CBO, and Mayagüez) emphasized the importance of the “development of engagement methods that encourage community collaboration and empowerment”. Jessica (woman, age 42, 7 years, Hispanic, NGO, and Comerío) mentioned that more efforts should be put into “advancing research, policy development, and the exchange of strategies for building resilience and responding to challenges faced by rural communities after disasters”.

Some of the participants underscored that there are “complexities involved in disaster response within different geographic areas”. Alejandra (woman, age 44, 11 years, Hispanic, GOV, and Mayagüez) emphasized “the necessity for a unified and proactive approach that integrates community involvement, technology, and a deep understanding of the unique obstacles encountered by vulnerable groups”. This highlights the need for a shift in disaster preparedness and response strategies—one that is all encompassing, adaptable, and sustainable in the long run.

The importance of taking measures was emphasized during discussions. Lily (woman, age 46, 10 years Hispanic, CBO, and Ponce) put an emphasis on dedicating time “outside of disaster periods” to equip communities with the knowledge to tackle issues effectively, enhance their resource capacity, and improve their capabilities. Rosa (woman, age 48, 15 years, Hispanic, ER, and Comerío) stressed the need to focus on all aspects of emergency management instead of solely prioritizing immediate response efforts as this would contribute to sustainability. “To create a lasting future we need to address emergency management from a perspective considering all elements of the mitigation, readiness, response, and recovery process. This approach helps us handle crises efficiently and sets the foundation for future sustainable development”.

The key aspects highlighted by the interviewees were the importance of customizing disaster preparedness solutions to suit the characteristics of communities and creating communication plans to encourage community cooperation and empowerment. Progressing in research policy formulation and sharing strategies are crucial for enhancing resilience in rural areas. It is essential to take a cohesive stance by merging community engagement while also equipping communities with the information and tools required for disaster preparedness throughout all phases of emergency response.

8. Discussion: Overcoming Challenges and Building Resilience

This study delved into the challenges that hinder disaster recovery in rural areas and aimed to find ways to strengthen community resilience. This investigation addressed the vulnerabilities of communities during disasters, as highlighted by Cutter and Finch (2008) and Hewitt (1995) [

13,

42]. The insights gathered from the 18 interviews with professionals in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria underscored the importance of adapting disaster response to suit the circumstances of rural areas. NGOs, CBOs, emergency responders, and government organizations underscored aspects concerning disaster preparedness and response. The present study uncovers four themes that are closely connected and play a role in understanding and enhancing disaster resilience and recovery in rural communities. These themes are not independent but rather intertwined, impacting each other in ways that shape how rural areas bounce back from disasters.

Existing Vulnerabilities and Community Resilience: The initial theme highlights the social, economic, and infrastructural vulnerabilities already present in communities that worsen their ability to handle and recover from disasters. Issues like resources, a lack of diversity, and aging infrastructure lay the groundwork for discussing the current management of resilience and potential improvements. Recognizing these vulnerabilities serves as a foundation for recognizing the obstacles to disaster response (Theme 2) and the diverse responses required across sectors (Theme 3). It also emphasizes the need for targeted strategies to boost long-term sustainability and resilience (Theme 4).

Obstacles to Response: The second theme delves into the challenges that impede efficient disaster response in rural areas, including bureaucratic red tape, insufficient funding, and logistical hurdles, especially distributing aid. These obstacles often arise because of the vulnerabilities that have been brought to light. Recognizing and understanding these obstacles are vital for creating plans that make use of community involvement and collaboration across sectors (Theme 3), which are crucial for overcoming these challenges and promoting resilience (Theme 4).

Strengthening Rural Response through Collaboration Across Sectors: This topic underscores the significance of community-driven methods and partnerships between sectors in dealing with the issues faced in rural disaster management. Insights from different fields underscore the importance of combining insights with external support to maximize efforts in responding to and recovering from disasters. Effectively addressing existing vulnerabilities and surmounting response barriers (Themes 1 and 2) heavily rely on strong collaborations across different sectors, which can also spur the development of sustainable strategies for resilience (Theme 4).

Approaches for Building Disaster Resilience and Long-term Sustainability: This theme explores strategies that can bolster the enduring resilience and sustainability of communities. It stresses the importance of policies that go beyond reacting to focusing on enhancing infrastructure, community education, and economic diversification. The strategies to boost resilience are shaped by recognizing vulnerabilities (Theme 1), overcoming obstacles (Theme 2), and calling for coordinated efforts (Theme 3).

These themes weave a story about rural disaster resilience and recovery. The analysis demonstrates the impact of vulnerabilities on disaster response, how collaboration can address barriers, and how strategic planning can promote resilience. This approach seeks to address the vulnerabilities and challenges faced by rural areas. Government staff, NGO personnel, community leaders in CBOs, and emergency responders have all highlighted aspects of disaster readiness and response from their individual viewpoints:

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs):

Julia pointed out the heightened vulnerabilities experienced by communities of color and those in rural areas during disasters.

Jessica highlighted the necessity for capacity building and training, especially for individuals in remote locations.

Emergency responders (ERs):

Tom discussed the significance of enhancing support in disaster response efforts.

Taylor stressed the need for tailored solutions that cater to community needs.

Rosa called for focusing on all aspects of emergency management such as mitigation, readiness, response, and recovery processes—instead of solely prioritizing immediate response efforts—as this would contribute to sustainability.

Government officials (GOVs):

Gerardo addressed the challenges faced in delivering aid to areas due to barriers along with feelings of neglect post-disaster.

Miriam pointed out the population decline resulting from school closures and families migrating in search of better living conditions.

Alejandra emphasized the importance of an approach that involves community participation and a deep understanding of the obstacles faced by vulnerable groups.

Community-Based Organizations (CBOs):

Ariel discussed the heightened vulnerabilities faced by adults and individuals with health conditions during disasters.

Beatriz highlighted collaboration across various levels to effectively respond to emergencies, emphasizing the importance of engagement.

Roberto stressed the significance of having individuals who understand the challenges actively participate in problem solving.

The results support the existing literature advocating an integrated approach to disaster recovery and stressing the significance of cooperation among different sectors, including the government, NGOs, etc., as discussed by Kapucu, Hawkins, and Rivera (2013) as well as Berke (2016) [

41,

67]. This study reinforces this idea by showcasing participants’ emphasis on efforts for response and long-term resilience building.

Moreover, the recommendations align with the existing literature, pushing for community engagement and policy development, which considers the socioeconomic and environmental characteristics unique to regions [

29]. The importance of this study for policymakers and planning/disaster professionals lies in the tools that it offers, including enhancing data integration, financial literacy, and access to training. This was highlighted by Godschalk (2014) and Freeman and Ashley (2017) [

10,

34]. By reinforcing themes observed in rural case studies such as delayed assistance and increased financial challenges, this study not only echoes the existing literature but also advances it by presenting practical experiences from people who work in rural regions recovering from major disasters.

Finally, this article’s unique contribution is its examination of the differences in disaster recovery and resilience building between urban areas. The focus is not on the barriers as described before, such as geographic limitations, transportation issues, financial constraints, and a lack of media attention [

6], but on how to be more resilient. Informants discuss the importance of promoting collaboration across sectors and involving the community to enhance resilience. It also highlights the importance of considering the economic and environmental aspects (flows of goods and services for example) of rural communities in policymaking and initiatives. Moreover, this study underlines the significance of enhancing data integration, providing financial education, and offering capacity building training to empower rural areas in preparing for and recovering from disasters.

9. Conclusions

This study contributes to the discussions on disaster recovery and resilience in rural areas by filling a gap identified in the existing literature. The present article provides a perspective across rural communities emphasized by Sanders, Laing, and Frost (2015), along with Dvir and Pasher (2004) [

40,

41]. The suggestions for improving long-term sustainability and resilience are directly influenced by this study, bridging the gap between discussions and real-world planning. The conclusions drawn from this study on disaster recovery and resilience, such as those highlighted in the article about rural regions post-Hurricane Maria, can be transformed into practical measures for policymakers, emergency planners, community leaders, etc., in various ways:

Policy Formulation: Policymakers can utilize this study’s findings to create regulations that cater to the specific needs of rural communities. For example, they might establish funding mechanisms that target rural disaster resilience initiatives or mandate upgrades to infrastructure that consider the obstacles present in these areas.

Allocation of Resources: Emergency planners could utilize the study outcomes to enhance resource distribution. By understanding the needs of communities, resources can be strategically positioned for swift deployment after a disaster, particularly in remote locations that are often inaccessible.

Training Initiatives: The insights regarding the necessity for accessible and relevant training could inspire emergency planners and community leaders to develop programs for capacity building accessible to those living in rural areas. These programs could emphasize skills such as aid, emergency communication procedures, and sustainable reconstruction methods that are directly applicable to rural environments.

Community Engagement Frameworks: Community leaders can establish structures for engagement that promote incorporating knowledge into disaster planning and response efforts. In times of crisis, communities may set up response teams and utilize gathering spots as information centers and resource hubs.

Information Systems: There is a call for data integration that could result in creating systems to monitor resources, vulnerabilities, and recovery progress. These systems can enhance planning and response efficiency and keep the community well informed and engaged.

By translating these insights into practical applications, those involved in disaster management can enhance both the responses and long-term resilience in rural areas. The present study emphasizes the requirement for strategies tailored to rural contexts, collaborative efforts across sectors, and the active involvement of communities to improve disaster recovery and resilience within rural areas. While this study may have limitations due to the size of the sample and the reliance on self-reported information, it offers perspectives on the obstacles and solutions in disaster recovery in rural areas that are potentially applicable to a wider context.

In the future, researchers may want to investigate additional rural communities to explore how well recovery plans worked based on some of the issues presented here like access to data, capacity building training, and the level of community engagement. Furthermore, by following these communities’ progress over the years, we can learn more about how resilient and sustainable their rebuilding efforts are and what new obstacles they encounter—especially following a new disaster event.