Abstract

Over the last quarter of a century, there has been a growing global interest in inclusive education, and the promotion of equality and acceptance for children with special educational needs. While some studies have explored sustainable practices for inclusion in international research, there is a notable lack of studies conducted in Pakistan that aim to identify best practices to not only promote inclusion, but also to sustain it over time. The current study uses a qualitative case study approach to explore one sustainable inclusive education setting in depth and identify the factors that contribute to its longevity. The thematic analysis revealed significant themes that reflect the practices that have enabled the institution to thrive for more than 25 years. These include the implementation of welcoming policies and supportive attitudes among all stakeholders, the provision of essential resources, the creation of adapted learning environments, the promotion of parental and peer support, the continuous professional development of staff, advocacy for acceptance and equality, and outstanding leadership in promoting inclusive support. The authors acknowledge the limitations of a single case study; however, this study represents the first attempt to provide guidance to institutions adopting inclusive education models in Pakistan.

1. Introduction

The term sustainability means the ability to maintain a certain rate or level, and is generally used to specify programs, initiatives, and measures aimed at protecting a particular resource or facility [1]. Education for sustainable development (ESD) emphasizes the importance of educational institutions in addressing social, economic, and environmental challenges, through the development of curricula that ensure the equal involvement of teachers, administrators, students, and the wider community in the adoption of sustainable practices [2]. Sustainability comprises four different areas: human, social, economic, and environmental, known as the four pillars of sustainability [1]. However, in the context of this research study, the focus is on social sustainability, although all four pillars overlap and are interconnected. When social sustainability is achieved, human, economic, and environmental sustainability can automatically be achieved as well [3]. Human sustainability aims to maintain and improve human capital in society [4]. Economic sustainability aims to keep capital intact [1]. Environmental sustainability aims to improve human well-being by protecting natural capital [5].

Social sustainability aims to preserve social capital by investing in and creating services that provide the framework for our society. Social sustainability focuses on maintaining and improving social quality, with concepts such as interconnectedness, mutual benefit and morality, and the importance of relationships between people [1]. It can be promoted and supported by laws, information, and shared ideas of equality and rights. Social sustainability encompasses the idea of sustainable development, as defined in the United Nations’ sustainable development goals [6].

Inclusive education advocates for the education of all children within the same school setting, regardless of their physical, intellectual, or emotional capabilities [7,8]. It is regarded as a fundamental component of civil rights. However, many educators express reservations about fully integrating students with special needs into mainstream schools [9]. Pakistan is a signatory to numerous global conventions, creating immense pressure to fulfill its commitments. The concept of inclusive education is reflected in the sustainable development goals (SDGs), which call for the inclusion of children with special educational needs in mainstream schools. Therefore, institutions must not only accept children with disabilities, but also support them successfully. In this country, however, many schools were not able to continue being inclusive schools, so they ceased their work [10].

This research study examined an inclusive school that has been in existence for 25 years. It is therefore necessary to identify the elements of the Praxis School that have enabled it to sustain itself. The analysis is based on an understanding of the sustainability of the school, in terms of the culture and values that the school officially supports. The purpose of this research study is to examine how the school community fosters a culture that is conducive to the flourishing and enduring success of its inclusive ideals. It is important to highlight the importance of the theme of “sustainability” in this study.

2. Literature Review

Over the past quarter of a century, there has been a burgeoning global interest in inclusive education, marked by a shift in its definition. Initially focused on advocating for the integration and support of children with ‘special educational needs’ in mainstream schools, it has evolved into a broader commitment to the inclusion of all learners [11]. Inclusive education is now widely recognized as providing an excellent education for every child, facilitating their learning alongside their peers in an environment that avoids segregation or exclusion in any form [12].

According to Fedulova et al. (2019), the core principle of sustainable development is ensuring that the progress of the present generation is consistent with the well-being of future generations [13]. Traditionally, intergenerational equity has been conceptualized as a harmony of needs [13]. The concept of sustainable development has broadened to include the promotion of greater tolerance and acceptance of people with disabilities, recognizing not only their equal rights, but also society’s responsibility to ensure equal opportunities for them.

Pakistan has also taken steps to support these children. The policy document reflects inclusive approaches to education, such as those outlined in the National Education Policy (2017) [14,15]. Pakistan is a signatory of numerous universal agreements and treaties through which the state has committed to guarantee educational provision to children with disabilities and endorse inclusive education. These include the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006, and above all, sustainable development goals (SDGs) comprising 17 goals and 169 targets set by the nations of the world in September 2015, assured to be achieved by 2031 [16,17,18]. Goal 4 of the SDGs narrates education and accentuates “inclusive” and rightful quality education for all learners. Target 4.5 of SDG 4 proposes the confirmation of equal access for children with disabilities to all levels of education and vocational training (p. 37) [16].

Akpan and Beard (2013) and Nilholm (2021) stressed the necessity for educators involved in special and inclusive education to have access to guidelines containing model practices for the teaching–learning process, as well as practical applications and technical support [19,20]. While numerous studies exist on model practices in developed countries, the literature on underdeveloped countries is scarce due to their constrained resources, lack of accessibility, and limited availability [21,22]. A number of research studies conducted in Pakistan have underlined that educators are beginning to promote the concept of inclusive education [23]. However, there is still a lack of research that focuses on the sustainability and evaluation of the successful practices that are being implemented. Shaukat (2022) also emphasized that there is a need to work on inclusive education models and assistive technologies to support inclusive education setups for the sustainable growth of society, in order to meet sustainable development goals effectively [15].

Inclusive education has become a global endeavor in many Western countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, which have enacted legislation to support inclusive educational practices [15]. Developing countries such as India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Hong Kong have also reformed their educational policies to emphasize the inclusion of learners with disabilities in mainstream classrooms [8]. These policies stress the importance of creating inclusive environments through collaboration among staff and school personnel, to meet the needs of learners with disabilities. Additionally, they highlight the necessity for adapted curricula and teaching techniques to accommodate the diverse needs of all students, emphasizing support for both special education teachers and regular classroom teachers in employing cooperative learning and collaborative lesson planning [15]. Effective implementation of these policies requires modified teacher education programs that ensure new graduates possess the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to teach in inclusive classrooms

Therefore, to address this research gap, the present study aims to identify and evaluate the successful inclusive practices implemented in one of the most sustainable inclusive schools, through a case study design.

3. Context of the Current Study

3.1. Research Setting

Government schools, commonly referred to as public schools, do not charge tuition and operate on a comprehensive admissions system that does not officially consider factors such as academic performance, ethnicity, religion, or the socioeconomic status of students’ families. Despite the abundance of public schools in Pakistan, the quality of education is generally perceived to be low, prompting many parents to opt for private education if it is financially feasible. Private schools, on the other hand, tend to offer a higher standard of education, but charge tuition, admission fees, and other maintenance fees. These institutions may be run by individuals, non-governmental organizations, or voluntary groups with an educational agenda, often supported by donors [24]. When it comes to supporting inclusive education institutions, according to Amjad et al. (2021), public school teachers have shown a reluctance to support inclusive education environments [25]. This may be the reason why parents prefer to send their children with disabilities to private schools if it is affordable for them.

It is worth noting that the international literature on inclusion, which initially focused on advocating for the integration and support of children with “special educational needs” in mainstream schools, has evolved into a broader commitment to the inclusion of all learners [11]. However, in this particular study, we focus on the inclusion of children with special needs or disabilities and highlight a success story of a school that promotes their inclusion. The current research study is situated within the private education system (referred to as K-V) in a major city in Pakistan. This school is an exceptional case, having maintained an inclusive culture for over 27 years. Furthermore, Praxis School caters to a diverse array of disabilities, encompassing hearing, physical, intellectual, and visual impairments. Additionally, it accommodates children with conditions such as autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Down syndrome (DS), cerebral palsy, and learning disabilities such as dyslexia and dysgraphia. It has been recognized by UNICEF for its authentic adoption of inclusive educational practices. What sets this school apart is its ability to provide education to disadvantaged socioeconomic groups, while sustaining its success over time. Also, the Praxis School has created opportunities to include children with disabilities in mainstream schools by creating a welcoming and accommodating environment for all children.

3.2. Research Design

This research adopts a qualitative case study design, which provides a valuable opportunity to develop a deep understanding of a particular event or entity through direct observation and data collection in its natural context [26]. To ensure triangulation, the research study used a variety of methods, in addition to primary data collection through interviews, including observations, document analysis, and field notes. Although the focus was on collecting, transcribing, and interpreting interview data, we encountered observations and policy notes that were pertinent to the themes generated and included them. In this particular case study, the focus is on a single site, an inclusive school called the Praxis School (pseudonym). The primary research method used was one-to-one semi-structured interviews with all the stakeholders listed in Table 1. It is worth mentioning that throughout the study, participant pseudonyms are consistently utilized alongside the excerpts. Prior to conducting these interviews, guidelines for the semi-structured interviews were formulated. These guidelines were developed according to the themes identified from the literature and covered areas such as teaching strategies, involving stakeholders, resource management, etc. Data analysis was carried out through open coding, following the methodology outlined by Strauss and Corbin (1998) [27]. Subsequently, themes were identified and presented in this study.

Table 1.

Participants selected for an interview *.

3.3. Sampling Characteristics

Researchers utilized a purposive sampling technique, which involves selecting a sample based on knowledge about the population and the research study [28]. In the context of a case study, purposive sampling entails choosing subjects based on specific characteristics [29]. Accordingly, participants were chosen by establishing selection criteria, as outlined in Table 1, which encompassed all stakeholders, including teachers, administrators, and coordinators.

4. Qualitative Thematic Analysis

The thematic analysis of the transcripts provided by inclusive educators primarily centered on practices leading to the inception of an inclusive environment and enabling the study site’s long-term sustainability. To gain a thorough understanding of each text, the transcripts and field notes underwent several rounds of reading and revisiting. Data analysis involved open coding, following the methodology detailed by Strauss and Corbin (1998) [27]. Subsequently, themes were identified and presented within this study. Some of the themes generated are discussed below, followed by a Section 5.

4.1. Welcoming Policies and Supportive Attitudes

According to Shaukat and Rasheed (2015), there is no singular model for how an inclusive school operates, leading to a variety of practices being created, adapted, and modified to achieve successful inclusion [30]. Hameed and Manzoor (2019) suggested that inclusive schools should be developed with the aim of being welcoming and supportive spaces for all of their learners, including children with disabilities [8]. One of the ways to demonstrate acceptance is to create welcoming policies and supportive spaces, which are evident in the Praxis School. Their perceptions and acceptance helped them to create a welcoming and inclusive school. It was noted that the Praxis School has a very strong policy of inclusion in its vision statement in terms of its purpose and the aim of providing inclusive education. It is important to understand that policy means a principle of action or administrative action [20]. The administration ensures the implementation of the school’s aims, which are reflected in the mission statement. The statement illustrates:

The Praxis School has an inclusive environment. This means that all pupils have an equal opportunity to succeed regardless of ethnicity, color, religion, special needs, behavioral and psychological abilities, and socio-economic background (Extracted from the school’s website).

The statement emphasizes that the Praxis School strives to cater for all pupils regardless of their background, ethnicity, skin colour, religion, special needs, behavioural and psychological abilities, and socioeconomic differences. This demonstrates their welcoming attitude and willingness to accept everyone. They support CWSN by helping them to succeed and this is one of the reasons for their sustainability. The following statement from the Director’s administration highlights the welcoming environment in which supportive spaces are experienced.

“Our regular students and teachers are all very welcoming. They never make them (CWSN) feel that they have a disability or that they are different. They are friends with each other and their friendship is impeccable. It has been communicated to the mainstream students and teachers that these children are welcomed first. If they do not feel comfortable, they are welcome to leave. The teachers continue to explain in class, as I have also explained in meetings, that the SEN children will be integrated with the mainstream students to ensure inclusivity and that everyone needs to cooperate and help. The mainstream children as well as the teachers are made aware that these children are a part of our school. They no longer need counselling and have accepted them as part of the school. It also reflects that school support is a key component that has enabled us to work sustainably for so long (Mahmud)”.

The inclusive education policies of the Praxis School, along with its goals and objectives, are observable in the school environment, which fosters inclusivity. This aligns with the concepts outlined in both the National Education Policy (2017) and the sustainable development goals (2015), as reflected in the research findings [14,16]. According to a coordinator within the inclusive setting:

“The concept behind inclusion is based on a humanistic approach. Inclusion, according to me, includes every child regardless of abilities or disabilities to achieve sustainable development goals. It can be said that the motive behind our school is to help and above all to include. Our school was established with a vision to cater to CWSN so that they can become a useful member of society (Zareen)”.

It is important to note here that a school can never sustain itself if it lacks realization. The teacher mentioned, “It is the basic right to acquire education. The prevalence of disability does not matter; it is the acceptance that matter (Rimal)”.

4.2. Supportive Space in the form of Resource Room and Library

According to Peters and Wals (2016), educators have a duty to cultivate the skills necessary for critical engagement with important issues and to promote practices such as forward thinking, integrative thinking, and dealing with complexity and ambiguity [31]. They also emphasize the importance of creating learning environments and supportive spaces that foster qualities such as caring, empathy, and solidarity. Kopnina and Cherniak (2015) echo this sentiment, emphasizing that education loses its purpose when students graduate into a society that does not embrace the values and perspectives they have acquired [32].

A very good example of a supportive space is the presence of a resource room. Resource rooms are classrooms where students with disabilities are taught and supported by special education teachers. These classrooms are usually run by special education teachers and occasionally supplemented by support staff [33]. This service is often used in inclusive educational institutions to support students with special needs. At the study site, the support room is used both for children with special educational needs and for general education students who require special instruction in an individual or small group setting for part of the day. One teacher stated:

“It is important to note here that sometimes a child without a disability needs extra attention and care. Individual needs are supported in resource rooms as defined by the student’s Individualized Education Plan (Aiman)”.

Pupils come to the resource room or are brought there for a variety of reasons. It was observed that children with special educational needs go there to access the teaching materials that better suit their learning styles and abilities. Sometimes the material taught in the regular classroom is above the student’s level and the support room serves as a quieter place where the student can work through the material at a slower pace. Bogdan and Kugelmass (2012) mentioned that a ratio of five students to one teacher should not be exceeded in the resource room, and students often worked with one teacher alone [33]. A similar practice was observed at the research site. A teacher stated,

“Very often, students also come to the resource room to be assessed and tested for academic screening (Rushna)”.

According to the staff working at the research site, the resource room provides a less distracting environment and a better chance at success. A teacher further endorsed that:

“The resource rooms also support the social needs of their students, as the small group setting is less hostile to CWSN (Talib)”.

It was observed that the resource room also provides opportunities for behaviour management. Teachers also mentioned that they often coach pupils on their social skills by helping them to take on leadership roles, such as helping another pupil to study. Another example of a supportive space for successful inclusion is the resourceful library [34]. The library was not only the place where children read books, but teachers used it as a place for storytelling, according to the interests and developmental levels of children with learning or intellectual/developmental disabilities. Teachers were also observed to use sign language when telling stories to children with hearing impairment. In addition to the motivational quotes on the walls of the library, there were a number of books, including encyclopedias, story books, and other subject-specific books. The library had a non-discriminatory atmosphere, where all individuals were treated equally and resources were shared harmoniously. It was noted that various materials, such as toys, blocks, pegs, crayons, pencil boxes, paint boxes, paints, coloured glasses, and numerous other resources were readily available and accessible to engage children with and without special educational needs. Their enjoyment was evident, and the library provided a welcoming and supportive environment for all.

4.3. Creating Adapted Learning Environments, Activities and Plans

Across the globe, schools are embracing individual education plans (IEPs), as mandated by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in the United States, in diverse formats [35,36]. Dempsey (2012) contends that without meticulously planned and developed IEPs, students with disabilities and/or additional needs will remain disadvantaged in terms of accessing quality education, and classroom teachers will struggle to implement widely recognized best practices [37]. The primary objective is to address the needs of the majority of students with special educational requirements, within mainstream classes, while also providing intensified support for those who require it. These individual education plans (IEPs) aim to ensure that each child’s unique special educational needs are comprehended and accommodated. The coordinator of inclusive setup stated:

“We do make IEPs. However, our student-teacher ratio is not appropriate to carry out IEP. We decided and preferred GEP (Group Education Plan). Whatever the ages of the children, if they have common needs, objectives, goals, and a similar IQ, then we devise GEP. If a child has behavior issues or issues of sitting tolerance, then IEP works not GEP. Resource teachers are responsible for creating IEPs (Zareen)”.

It is important to distinguish between individualized education plans (IEPs) and group education plans (GEPs). IEPs are tailored to individual needs and are primarily required for children with behavioral disorders (BDs), whereas GEPs are effective in addressing the common needs of students, regardless of age, who are grouped in groups of five (as observed during classroom assessments) to facilitate the achievement of desired goals. The decision to use IEPs or GEPs is usually made by the teacher, in collaboration with a team of coordinators and therapists. It is also worth noting that the implementation of IEPs requires the presence of a resource teacher.

The responsibility of a resource teacher is to focus on providing extra help and individualized instructions to students with disabilities or special needs. On the other hand, helper teachers are available to help all students in every class. The resource teachers are different from the helper teachers, as they are hired for individual children with severe or unmanageable behavioral issues.

In addition to facilitating inclusion, a key challenge for educational institutions is to ensure the academic success of CWDs. This is a key area where the teacher can provide significant support. In this regard, there is evidence that adapted learning platforms and objects influence their performance [38]. The present research study explored the certain areas of weakness that hinder CWSN and their academic success. A teacher stated:

“During the early years, we focus on fine motor skill development. Their motor skills are undeveloped to the extent that they cannot hold a ball. Their cognition is fine. For instance, we ask them to find things from a sand tray. We make them do the sorting. We hide numbers/alphabets in the sand they need to take out. This develops fine motor skills. This happens in early learning. In higher grades, they know it well. Our physical training teachers work on fine motor skills. When these are worked on the probability of academic success increases (Farina)”.

It is important to note that eye–hand coordination is a challenge for CWSN, which can be resolved through muscular exercise and activities like dot-to-dot to help develop coordination between the eye and hand. The teacher stated that these exercises are conducted on a regular basis. Another teacher shared an incident and stated:

“There was a child named Ray, who was good at Urdu (National Language of Pakistan). I observed that his mind and hand do not go together. He could pronounce the Urdu alphabet but could not write despite holding his hand. I told the mother that he had a problem. He needs muscular exercises. He should do dot-to-dot or use locks, and color locks, and match them with colors. His weak hand-eye coordination hampered his academic success, but we made him do muscular exercises and he got better. Their academic performance improved, therefore, we need to work on weak areas of CWSN to enhance their academic performance (Kainat)”.

Children with special educational needs also face challenges retaining information and need support in this regard. Hameed and Manzoor (2019) observed that active methods of learning increase the student’s motivation and improve their retaining power [8]. A teacher stated:

“Repetition is a must. Whatever we teach in a class we assign it as homework. We repeat many times. Like if I do board reading with them, I just do not begin with a new topic I revise the previous work. As for children with special educational needs, we do more revision. They have short-term memory, which is why they need repetition. If they do not repeat/practice they forget (Rina)”.

There has been an augmented emphasis on inclusive education [39], however, there is a lack of focus on providing students with intensive special support [8]. Children with special educational needs face difficulty while performing day-to-day activities, but activities for daily learning (ADLs) are a “sustainable solution”, as mentioned by the coordinator (Rushna). It was discovered that there are separate classes for ADLs where CWSN are trained. A coordinator stated:

“For ADLs we have a hygiene period, we teach them how to eat with a spoon. We taught them basic cooking, how they groom themselves, how to cut nails, and above all how to keep them clean. A few areas of ADLs like buttoning and unbuttoning incorporate fine motor skills. For another activity of ADLs, we dedicate a whole period, for instance, the hygiene period, and table manners. With time they get trained and can perform ADL independently and confidently, for instance getting dressed up and eating on their own. For these children, functional aspects are more important. There should be more focus on functional activities (Rabia)”.

It is the team of teachers, therapists, and psychologists who decide and plan ADLs to enable children to be functional. Hameed and Manzoor (2019) stated that an inclusive classroom, where activities of daily learning and activity-based learning are practiced to train CWSN, is a great opportunity and a reason for sustainability [8].

4.4. Improving Parental Attitudes and Practices and Providing Parental Supports

According to Naznin et al. (2023), in addition to various other obstacles in the education of children with disabilities, parents pose some challenges, due to inadequate infrastructure and resources to support children with special needs [40]. Many parents in low- to middle-income economies lack the financial means to cover additional expenses for transportation, educational materials, and therapies. Moreover, they often encounter social stigma when caring for these children, leading to feelings of depression and mental stress, thus necessitating psychological counseling. At times, parents pose a hurdle, making it difficult to convince them to acknowledge reality and provide support in alignment with the school’s efforts. Haider et al. (2016) stated that with the help of parents’ support, inclusive education setups run more smoothly [41].

The analysis revealed that the secret behind the sustainable practices of the Praxis School is their open-door policy, which means they welcome and support not just children with special educational needs, but also parents. Some parents also came to the Praxis School for a counseling session. The coordinator of an integrated setup, who is herself a foreign-qualified child psychologist, stated:

“To counsel the parents, we invite them. Whatever we do in school with CWSN, it all goes vain at home. Therefore, we call parents to explain how CWSN should be handled. It is not just the professional development of teachers, but the counseling of parents is very important, so for counseling them and helping answer their queries seminars and workshops are conducted (Rushna)”.

Another aspect in which parents require counseling pertains to their feelings of depression when caring for their children with disabilities. Teachers provide guidance and encourage them to remain patient. According to the director of administration:

“The parents need to be counseled. From me to the coordinators and the teachers all are concerned about the parents and sometimes it becomes very difficult to counsel them. They are not ready to accept the intensity of the disability and the placement of the children in the classes according to their needs. The parents sometimes seem reluctant to take care of the children with special education needs as they have more focus on their children who are without disabilities (Mahmud)”.

Parents of children with disabilities often lack the expertise to assist them in achieving educational milestones. In such cases, the school provides additional support to help parents reach the school’s educational objectives. The coordinator stated:

“I ask teachers to make WhatsApp groups with the parents and I prefer that whatever we teach a YouTube link needs to be sent. We ask parents to keep on playing that link for their child as the teacher teaches for 45 min, but for the purpose of retaining it has to be played at home [CWSN has retention issues] so the concept will be consolidated. We teach them for double periods or so but need to be revised at home to retain it (Zareen)”.

The aforementioned strategy has proven effective in enhancing retention and memory capabilities. Given that children spend significant time with their parents, parental involvement becomes crucial to effectively addressing the needs of children with special needs (CWSN). Such involvement is essential, as parents are integral members of the collaborative team. A teacher of English stated:

“We need the support of parents, if it is not then we cannot do miracles. They are with us for six hours, and the rest of the time they are at home. If parents think that they are putting their child in school and that school will do miracles, it is not possible. The parents should get help from the school to know whatever is taught to them, and make them practice at home like manners, how to sit/speak/how to use tissue paper/how to make use of a dustbin (Amber)”.

Parental involvement is essential, as parents, teachers, and students form the three corners of the triangle. If any of these elements are absent, objectives cannot be met, and for with children with special needs (CWSN), the responsibility of the remaining stakeholder is augmented.

Naznin et al. (2023) highlighted that the lack of financial resources among parents poses a significant obstacle to the education of children with disabilities [40]. A similar barrier was reported in this study, where parents are hesitant to enroll their children in schools due to the high fees charged to accommodate CWSN. For over two decades, the Praxis School has diligently worked towards the inclusion of all learners with disabilities, striving to create not only a supportive, but also an affordable environment. Their comprehensive societal approach is evident in their commitment to not only integrating children with special educational needs, but also accommodating them within an affordable fee structure. The coordinator of inclusive setup stated:

“We don’t differentiate based on socio-economic class, neither our children nor parents. The parents struggle and they want the children to be educated. We offer a concession and fee reduction packages. Although the fee structure is very nominal as compared to other setups”.

The affordable fee structure of the school solved the problem of parents and enabled them to get involved with the school and their CWSN effectively, and the system has been sustained so far.

According to Bywaters et al. (2003), parents may sometimes hesitate to enroll their children in school, or may express dissatisfaction with the inclusion of their disabled children [42]. To ensure children’s safety and address parental concerns, parents are encouraged to visit classes and observe how their children are being taught. Additionally, this practice helps the school visually demonstrate to parents that similar strategies can be implemented at home to facilitate children’s rapid learning and retention. The director of administration has adopted an open-door policy for students and their parents. He stated:

“I always ask my parents to go upstairs [Integrated and Inclusive setup are upstairs] and see our setup. We have maids upstairs to help our children. We have kept dresses of every size. In case something happens we clean them and make them change. The parents observe all these things”.

Anuruddhika (2018) stated that activities of daily learning are multifunctional and can support CWSN in multiple ways, especially with the help of parents and teachers, including sports teachers [43]. These activities not only develop fine and gross motor skills, but also help in their practical life.

4.5. Universalization in Communication through Professional Development of Courses

Teacher education programs serve an important function, not only in facilitating teaching and research, but also in fostering collaborative leadership around sustainability and inclusion initiatives within their respective communities [44].

In addition to enhancing teachers’ professional development and fostering inclusivity, it is valuable to delve into the collaborative role of teachers. Teachers form an interconnected network, where they can share newfound knowledge and insights. Through such exchanges, teachers support one another in articulating their current practices and aspirations. This cultivates a common language of practice, facilitating detailed discussions on pedagogical approaches. Without this shared language, teachers may struggle to explore innovative teaching methods for children with special needs (CWSN). This concept of a shared language of practice is evident in the school’s practices, contributing to the sustainability of its framework. It serves as a vital mechanism for teachers to learn from each other and engage parents in the educational process. Teachers who have undergone professional development programs can effectively train their peers, a practice observed within the school, exemplifying collaborative teamwork. Unlike expensive professional development courses, the concept of a shared language is practical and cost-effective, playing a pivotal role in sustaining the school’s framework. A coordinator stated:

“The diploma of behavioral management is done by almost all teachers. A famous psychologist was the facilitator of the workshop on behavioral management. We conduct training workshops for parents also. If we have a teacher trained from some other institution, then we involve them. We conduct workshops on weekends. We share teaching and behavioral management techniques. If workshops are conducted by renowned institutes other than our school, then the school pays and we attend the workshops. The training helps us. We train each other (Rushna)”.

The teachers at the school are big proponents of professional development courses. The administration pays for their teachers to take professional development courses held outside the school and motivates them to get trained. A teacher emphasized,

“It is the involvement of all stakeholders as without teamwork it is not possible to manage CWSN (Rushna)”.

There is also a recognition that the development of inclusive practices is likely to challenge the thinking of those within a school. This means that school teachers have to be skillful in encouraging coordinated and sustained efforts, based around the idea that changing outcomes for vulnerable groups of students is unlikely to be achieved unless there are changes in the behaviors of adults. This is witnessed in the setup.

The school community comprises a range of members, from students to their parents, helper staff, teachers, coordinators, and administrators. They have an integrated setup as well. Therefore, in this case, there is collaboration through an integrated and inclusive setup. The coordinator of integrated setup stated, regarding coordination and teamwork, not just amongst the teaching teams, but across the whole school:

“We have perfect cooperative teamwork under the supervision of the director of administration. We have perfect coordination with the coordinator of inclusive setup initially, for six months a child continues working in both setups. Then slowly and gradually after overcoming their weak areas we permanently shift them into an inclusive setup. We fear that if we completely shift then there can be a relapse of certain behaviors like throwing tantrums and resisting socializing. That is why we collaborate regarding children before shifting them completely to an inclusive setup (Rushna)”.

The professional growth of staff members also aids in their comprehension of children’s cognitive abilities. Cognition pertains to how individuals process information and problem-solve. Teachers emphasized the strengths of children with special needs (CWSN), which were nurtured within an environment that fosters support and acceptance. They perceive the robust cognitive capacities of CWSN as advantageous, facilitating their work and enhancing their integration into the environment. An English teacher provided an illustrative example:

“Their cognition and visualization is good and can do matching activities well. For instance, In English, we have cards with the beginning sound. I have pictures and alphabet cards. The pictures are stuck on the board, say 5 pictures, now the alphabet cards are with these children. The children need to paste/tag the cards of the beginning sound with the picture cards on the board (Amber)”.

The statement underscores the remarkable cognitive capabilities of these learners, which seamlessly and efficiently facilitate their accommodation within the setup. The teaching approach described above caters to these learners by employing activity-based methods. Through the utilization of engaging resources, children are supported in simplifying tasks, exemplifying an ideal instance of learning through active methods.

The professional development of teachers also enables them to engage all faculty members, including those specializing in physical activities, to utilize their expertise in engaging and educating students through physical education. The taekwondo/sports teacher said:

“During the PE sessions, we focus and work on gross motor skills by training them to walk backward, and kickball jumps in place with both feet. They run in a circle. They also perform taekwondo. It cultivates self-confidence in children with special educational needs that I can do. It is not a matter of winning or losing. It is all about training themselves to compete with others how to overcome barriers and become strong (Talib)”.

A physical exercise, sports, and taekwando teacher also mentioned,

“Co-curricular activities play a pivotal role in the life of a learner and help in the overall personality development. A physical trainer who is well-versed in the development of fine and gross motor skills development is a need of the day. If these areas are worked on, academic success can be achieved (Talib)”.

4.6. Promoting Acceptability and Equality in the Society

The acceptance of children with disabilities poses a significant challenge. Frequently, parents find themselves unprepared to embrace their children, influenced by societal pressures [45], as does society in general [46]. Prevailing educational and social norms often perpetuate disparities, hindering the progress of students with special educational requirements. Therefore, fostering success for every learner necessitates a critical examination of existing practices and an active commitment to establishing an inclusive teaching and learning atmosphere that champions equity. The concept of equity can be learned from the Praxis School. They do not make a child with a disability feel that they are different, or they are not part of society. They provide a similar environment to that offered to other children without special needs. The teacher in charge of inclusive setup stated:

“An inclusive classroom climate embraces diversity and creates an atmosphere of respect for all. There are a few more things that are very important for a school to become an inclusive school and that is patience in confronting big challenges (Ghazal)”.

The researchers state that schools focus more on academics than on communities [39]. In the current research study, it is explored that the school focuses more on social bonds, thus creating an inclusive environment, where there is acceptance of CWSN.

“Acceptability leads to sustainability (Rabia)”.

A coordinator further added:

“As soon as CWSNs are seen in the community, they will be accepted. What is happening now in our context we hide them? Treat them as normal human beings. If we are catering to them but they still are not functional, then what is the point? Pedagogy is secondary and will take care of it if the flow and momentum of acceptance of CWSN need to be developed and that can be done through awareness and increasing acceptability (Rushna)”.

Corrigan (2004) distinguishes between two forms of stigma, self-stigma and public stigma [47]. Self-stigma occurs when an individual labels him or herself as socially unacceptable, while public stigma refers to negative perceptions held by society. Both types of stigma contribute to the lack of acceptance of children with special educational needs, posing significant challenges and psychological distress for them. The director of administration and the teachers emphasize the crucial issue of acceptability. He expressed deep concern about this matter, believing that sustainability is ensured through fostering an environment of acceptance towards children with special educational needs. Sensitizing parents, teachers, and students about the inclusion of these children is a significant aspect.

“No one is ready to accept them, nor even their parents. The parents say these kinds of statements. Why should we invest in them? The school caters to them with a mission to offer affordable quality special needs education to disadvantaged learners affected by disabilities. Create a safe and compassionate environment, which encourages pupils to reach their full potential in an atmosphere of mutual respect (Mahmud)”.

A coordinator stated,

“These campaigns are organized at the school quite frequently where counselors try to reduce stigmatization and as a consequence, acceptability is increased. The setup sustains because of these campaigns and workshops (Rushna)”.

Moreover, students participate in commemorating various disability awareness days, such as the International Day of People with Disability (IDPwD) and World Autism Awareness Day for children with ASD, aiming to foster acceptance. Diverse activities are organized during these occasions. The administration perceives these celebrations as valuable opportunities to raise awareness and enhance acceptance.

The teacher stated:

“We celebrate different days where we invite parents. We plan and carry out so many activities on these special days. Play with playdough, strengthen hand muscles, and develop control over the fingers. Activities like rolling with hands or a rolling pin, hiding objects such as coins in the sand tray, or just creative construction. Another activity is rolling the playdough into tiny balls by using only the fingertips of the thumb, index, and middle fingers to flatten the playdough on a surface and make a design in the playdough with a toothpick. Similarly, one another activity is the use of Sensory Trays—Practice making marks in different sensory materials such as gel, sand, or flour. CWSN even writes on rice and gel. These are a few examples of how we celebrate the days related to different disability types (Kainat)”.

At the Praxis School, inclusivity is the core of its mission statement. A teacher stated:

“We have a good peaceful time where all are accepted and enjoy movies, stories, and poems. When both of them, a child with special educational needs or without getting busy watching a movie or listening to a story, or celebrating disability days looks equal. You cannot differentiate even. They both look the same. They are so happy listening, watching, and celebrating the same thing. A child with a disability never feels that he/ she is different from others (Amber)”.

This sort of peaceful environment can be a source of sustainability. “A feeling of belongingness”, as stated by the director administration, is at the core of the setup.

4.7. Effective Use of Peer Support

Children with special needs that are integrated into mainstream settings frequently encounter social rejection from their peers without special needs [48]. According to Kuutti et al. (2022), the segregation experienced by children with special educational needs and the definition of ‘special needs’ itself can often be perceived as stigmatizing [5]. Nevertheless, the Praxis School embodies a robust support system, evident in the peer support it offers.

In the current research study, special needs children attending inclusive schools were found to have positive connections with the entire school community, particularly with teachers and peers, including both disabled and non-disabled children. An English teacher shared an incident illustrating how peers assisted children with disabilities who struggled to differentiate between exercise books for English language and literature. A teacher stated:

“They help in packing their bags and getting them their lunch box. When they cannot differentiate between the exercise books in the English language and literature, children without disabilities help by putting colored labels on them so that they can learn to do it next time on their own. The peers motivate them and help them to start working independently. They always tell them, “You can do it (Amber)”.

Another aspect worth mentioning, which reflects the peer supportive environment, is how they handle CWSN. During observations, it was noticed that child with special needs fell down, then a child without a disability came and picked him up and provided him with first aid. The director administrator reflected:

“Our regular children get naturally trained. They help us. If a special child falls in particular children come and pick them up, and provide them with first aid. Yes, we have made the environment very inclusive. It is very welcoming (Mahmud)”.

The teachers at the school also demonstrate a strong commitment to assisting children with special educational needs. Additionally, they tactfully suggest alternative arrangements to parents of typically developing children, who may feel uncomfortable around students with disabilities. These educators exhibit pragmatism, knowing when intervention is necessary and when it is not. Their approach emphasizes the provision of as much support as possible to children with special needs. The overarching aim is to ensure all students feel valued and equal. Embracing this mindset fosters an inclusive environment.

“We believe in making them feel equal. Both support each other. If we develop this sort of thinking that he is incompetent or cannot do it, then inequality will be created, and that we do not want to happen at all. We want them to know that everyone is a normal human being. Our purpose is to make them feel happy and comfortable in the inclusive setup. I tell my children we all are friends. They are also your friends. I counsel them to be good with them. I tell them that these children are having a problem. If you do not cooperate, Allah [Lord] will be angry. These ways work. We sensitize them. They understand. If I shout and say don’t irritate them. Why are you doing this, then they will not listen and next time they hit and pass by, but if I handle both with love then a positive classroom environment is created (Mina)”.

In the scenario described, children with and without disabilities collaborate alongside teachers, and both are supportive of each other. Beyond pedagogical approaches, the school prioritizes flexible rules and accommodations. One fundamental principle is that typically developing children are expected to adapt; otherwise, they may seek enrollment elsewhere. Parents are informed of this expectation, which serves as a transparent declaration of the school’s commitment to inclusive education for children with special needs.

4.8. Exceptional Inspiring Leadership Is a Core Element of Sustainability

Leadership involves guiding an organization, institution, or group of individuals, often entailing risk-taking and challenging existing norms [49]. Effective leaders inspire others to pursue new and improved goals. In the context of the school, its leadership defied conventional practices by offering inclusive education at an affordable cost, contrasting with other institutions that charge high fees for inclusion.

Leadership plays a pivotal role in ensuring the sustainability of any program, particularly in fostering inclusion. A patient, determined, honest, and resolute leadership can pave the way for inclusive practices. The director of administration of the institution exemplifies these leadership qualities, demonstrating a commitment to prioritizing children with special needs (CWSN). Through his inclusive approach, he has successfully sensitized and motivated all stakeholders within the school community, emphasizing the importance of accommodating CWSN. His dedication and determination are evident in his statement:

“Inclusive education is just to give a chance to every child, whether the child has the ability or difficulty or anything whether they afford it or not. Whether the child deserves that opportunity is not for us to decide. So Alhamdulillah (praise be to God) we have included those who need extra help. They need a chance to be a part of school life. The literal meaning of inclusive is just to include them. Why deny them? I don’t want to deny them. I don’t want to deny anyone (Mahmud)”.

The director of administration’s vision is grounded in a significant concept advocated for by the Islamic religion and teachings, emphasizing education for all and support for marginalized individuals. Their intention is to ensure that no one is deprived, reflecting a strong belief in their attitude. They firmly believe that working for children with special needs (CWSN) garners support from Allah (God). Their intention is rooted in the conviction that they are serving a purpose, supported by the strength and resources provided by a higher power. The director shared the story of how it all began and why they chose to establish the school to assist children with disabilities:

“The Inclusive setup was started because of one of my relatives. She has a son who had signs of disability [diagnosed in different countries by different doctors]. He was an adult of 37/38 years. He was a normal child when he was born. But because of some mistakes of doctors [he got disabled]. That makes me feel sorry. There were a couple of people coming in and asking for help. But, I told them at that time it was a regular school. A couple of families came to me and said that their children are slow learners. They were reluctant to say, “My child is a special child.” Or he is an autistic or ADHD child. [To be very honest at that time I did not have an idea of all these special problems]. I asked one of the Mothers, whose son had a disability to come and help me out and we could see what we could do. She used to come for half of the day as the son was younger.

In another incident, I met the parents of a boy and they were sitting in my office. I was talking to them. A boy, an aged boy [older than what we perceive as a young child], opened the door of my office and said, “I am a normal person.” That clicked and I said let’s go with it. I hired a psychologist and a speech therapist. It was a burden on my pocket at that time, but the school afforded it. It was the beginning and slowly and gradually Alhamdulillah, we set up new rooms for them, and a psychologist, and special educator were hired. The helping mother also stayed with us for a few years and then I started getting professionals. And that is how we started (Mahmud).”

The establishment of the school is also based on a humanistic approach and is sustained because the motive is to support CWSN, who are the priority of the school. The director stated:

“In the beginning, I gave a straight answer to parents that there are other schools for your children [Children without disability] to take them there, but I will not let these kids [children with special needs] leave this school. I know when we refuse these children will not get better, but their condition can get worse. Here [in our setup] parents are satisfied as they are catered to according to their disability type (Mahmud)”.

It is very important to note here that the school prefers to accept children with disabilities, as there are few places that cater to them. Additionally, they treat them in accordance with the type of disability. The director said that they installed the air conditioner for the children with Down syndrome (DS), as if they feel hot they cannot study, although it was difficult to afford the expense.

“If an air conditioner is required, we provide it. In a couple of rooms, we have air conditioners but I cannot afford to have one in every room. Children with special educational needs feel restless when it is very hot, air conditioner is their need. All the facilities are provided here. When parents know at this fee all the facilities and professional help are given to their children they feel happy (Mahmud)”.

The financial constraints are visible in the above statement. He added:

“I am not stingy in spending money on these students [Children with special educational needs]. When we hire someone for another setup [referring to O levels etc.] I negotiate on money matters but for my inclusive setup, I spend. You see, here you need more helpers and teachers. Each special educator has a helper. That is a big task, in terms of finances, to be carried out (Mahmud).”

Connecting this with the many reasons for its sustainability, is the affordable fee structure. There are inclusive schools, but they charge too much in the name of catering to disabilities.

The director of administration also shared the other schools are also working to make their setup inclusive. However, it is not easy. It demands sustainability, acceptability, and accountability, as well.

“I know a couple of schools are trying. I know they are charging about 50,000 rupees. I am charging 10% of it. Why should I take advantage of someone’s weakness? What is the benefit of taking advantage of someone’s shortcomings? After how long are you going to live, tell me? If you do something good, then people will remember you (Mahmud)”.

The coordinator further discussed the setup and stated that:

“The major distinguishing feature between us and other schools is that we give admission to the differently-abled child and we allow them to get educated alongside their regular peers. The fees we are charging are lower than other schools. We also have children from middle-class and lower-middle-class families. We cater to the middle to lower-middle class. The bank balance is not important to us; we explore opportunities for all. We look at how we can admit a child and what we can do for a child (Rabia)”.

However, at the school, the leadership also instructed that they never give false hope, and share the realities and associated challenges of these children.

The coordinator of inclusive setup said:

“We all try not to say no to anyone. It has become very challenging for me as we do not make fake promises, and neither does our management. If a child is of pre-foundation level and is not age-appropriate, then we will not make any fake promises. We try to help a child as much as we can. At least we work on developing sitting tolerance, socialization, and communication (Zareen)”.

The above statement suggests that the leadership is deeply committed to assisting children with special needs (CWSN), yet they communicate the reality to parents. As mentioned, if a child’s developmental level is below the expected foundation level and not aligned with their age, parents are informed accordingly. It is crucial to recognize that this situation may arise when a child joins school late, resulting in their level remaining stagnant while their age surpasses the appropriate threshold. In such cases, maintaining the same academic level becomes impractical. The school prioritizes transparency by providing parents with an accurate assessment of their child’s abilities, rather than making false assurances. The leadership of the school acknowledge this challenge and view it as a significant issue. Consequently, they promptly inform parents upon enrollment, to prevent wasted time and resources.

The same idea resonated with the teacher in charge of inclusive setup, where she discussed how labeling a setup inclusive does not make it inclusive. It needs planning, organization, staffing, direction, coordination, and accountability.

“There is a need to create awareness through social platforms. Inclusion is not a “fancy term.” If schools are inclusive, then they truly need to adopt it. You are running a normal setup and labeled it as inclusive. What is this? (Rimal)”

The same concern was shared by the director of administration:

“The parents had this mindset that my child was coming from a regular school. When they came to us we told them that their child has special needs. The parents asked us if our child was coming from a regular school, how did you assess and say that our child needs special care and attention? We need to explain to them and then tears troll down [My tissue box gets empty]. I don’t like dishonest people. I won’t lie. Be honest and then your child can be honest. My teachers are honest. It was not the parents’ mistake. It was the fault of those schools who admitted them in the first place without telling them that something was wrong with the child (Mahmud)”.

The above statement is an eye-opener, as there are schools that have registered as inclusive schools, but lack planning, organization, staffing, direction, coordination, and accountability. What happens, as a result, is that when they are unable to handle CWSN, they ask parents to take them to a special school. The flaw is in the school, not the child, but it is a dilemma. In these circumstances, a school that has sustained itself as an inclusive school is like a ray of hope. Therefore, the exploration of such a school can enlighten other schools in terms of pedagogy and sustainability, and the current case study is an example.

However, altering the cultural norms that exist within a school is challenging, especially within a setting that is faced with so many pressures in terms of dealing with parents who are not ready to accept the problems of their children, requiring pragmatic decisions regarding the transition from an integrated to an inclusive setup. For example, asking parents to let CWSN into vocational education, or dealing with schools that are exploiting CWSN and their parents. Therefore, leaders at all levels, including teachers, parents, and other community members, have to be primed to evaluate their own circumstances, recognize local hurdles, and design a suitable improvement plan, as well as offering support for implementing inclusive educational practices and useful approaches for observing parity in education. The school explored here can be a guiding source in this regard. At this school, CWSN own the setup, as they feel that they are included, respected, and valued by others in an inclusive classroom setting, which is reflected in the sustainability of the setup.

5. Discussion

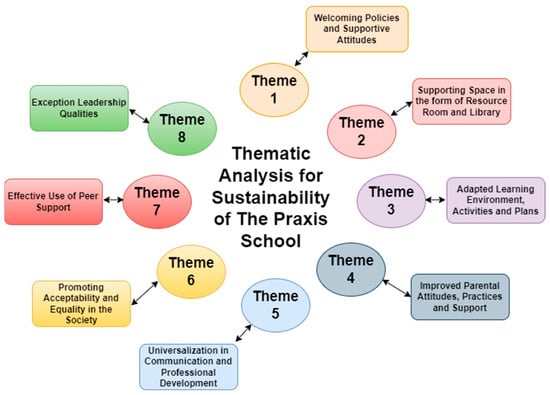

The study focuses on the success achieved by the Praxis School, which has thrived for over 25 years in a societal landscape where other inclusive institutions have struggled. It examines the key strengths and practices of inclusive school, offering valuable guidance for schools facing challenges or considering transitioning to an inclusive model (refer to Table 2 and Figure 1). The aim of this research study is to discuss how the school community creates a culture in which inclusive ideals can thrive and be sustainably successful.

Table 2.

Themes and overarching concept of each individual theme.

Figure 1.

Summary of themes generated to identify sustainability factors of the Praxis School.

Ensuring successful inclusion requires institutions to establish clear policies and guidelines that prioritize the inclusion of children with special educational needs, and effective communication to all stakeholders. Both the National Education Policy (2017) and the sustainable development goals (2015) explicitly underscore the importance of supporting children with special needs [14]. The success and sustainability of inclusion in the researched institution are evident from its policies and vision. These findings resonate with the research conducted by Kuutti et al. (2022) and suggest that both leaders and teachers should believe in the abilities of children with special educational needs to develop independently, which contributes significantly to the sustainability of the Praxis School [5].

The study highlighted the resource room and library as vital assets that contributed to sustaining the Praxis School. It is evident that the school effectively utilized both these resources to foster a non-discriminatory environment and support students with and without disabilities, in accordance with their individualized education plans. Other researchers have also emphasized the effective utilization of these resources as being crucial for the successful inclusion of children with disabilities [33,34,50]. This demonstrates that the school has embraced and upheld international standards of inclusion, which significantly contributes to its success.

The context of individualized education plans (IEPs), group education plans (GEPs) and activities for daily learning (ADL) in fostering successful inclusion has been extensively discussed in the literature [8,35,36,37,51]. According to Hameed and Manzoor (2019), an inclusive classroom that incorporates daily learning activities and activity-based learning to support children with special needs (CWSN) presents a significant opportunity and contributes to sustainability [8]. Thus, it is advisable for inclusive schools to regularly implement daily learning activities to improve the functional abilities of CWSN. This approach helps them carry out their daily tasks independently and efficiently [5]. The research study has further revealed that the sustainable success of the Praxis School is rooted in its adherence to international standards for accommodating children with both severe and mild disabilities, through the implementation of IEPs, GEPs, and ADL.

According to Naznin et al. (2023) and Bywaters et al. (2003), ensuring the successful inclusion of children requires providing parents with financial, social, and moral support, as well as educating them about the complexities involved in nurturing children with disabilities [40,42]. Another significant factor contributing to the school’s success is helping parents not only to change their attitudes towards their children and help them accept the challenges associated with raising CWSN, but also equipping them with the expertise to handle their children’s education and other aspects. Additionally, parents are offered counseling sessions to help overcome the stigma associated with raising a child with disabilities. School authorities also assist parents in alleviating the financial burden associated with nurturing and educating these children.

Professional development of teachers to promote inclusive education is another crucial strategy endorsed by scholars [44]. The sustainability of the Praxis School also hinges on providing teachers with training opportunities to disseminate best practices to all staff members for accommodating and educating these children. Consequently, there is a universal understanding of effective activities and practices throughout the institution, enhancing its effectiveness and sustainability. The majority of the research participants in the Praxis School emphasized that there is a need for more opportunities for professional development of teachers. They also emphasized that they had received some high-quality professional development courses, so they can cater to the children special needs within their inclusive classroom setup. It has been discussed that for effective inclusion practices, the professional development of teachers should comprise assistance with lesson planning and training on suitable teaching methods, using resources that will help teachers to accommodate a range of special needs in inclusive classrooms.

Parents often struggle to accept their children with disabilities, due to societal pressures, a sentiment echoed by broader society. These societal expectations are reinforced by prevailing educational and social norms, resulting in obstacles for students with special educational needs [45,46]. Fraser (2007) stressed the importance of acceptance and inclusion, which fosters representation [52]. Stigmatization not only distresses children with special needs, but also affects their families, endangering their social standing and leading to misrepresentation [15,52]. The Praxis School is recognized for its robust educational programs, designed to cater to all learners and promote societal acceptance. Additionally, the school prioritizes the social and emotional development of children, a characteristic stemming from its inclusive community ethos. They also provide awareness campaigns and workshops aimed at helping parents and communities to recognize their integral role within society, emphasizing their equal importance alongside other members of the community.

Children with disabilities frequently face rejection not only from society at large, but also from their peers [48]. However, the Praxis School has cultivated an environment where peers not only accept classmates with disabilities, but also collaborate as a community with teachers and other staff members to support and integrate them as valuable members of society. The effectiveness of peer support programs has been demonstrated in various educational settings [53], contributing to the sustainability of schools like the Praxis School. It is accurate to state that the Praxis School is actively collaborating not only with children with disabilities, but also with parents, peers, community members, and broader society, to achieve their objective of successfully integrating children with disabilities and empowering them to be valued members of the community. The findings resonate with those Hameed and Manzoor (2019), who discussed that there is a need to defeat inequalities in schools [8]. The current school has defeated inequalities by being inclusive and adopting the right methodology at the right time. Therefore, the Praxis School stood out and has thus sustained. The leadership is collaborating and supporting other schools that are intending to practice the inclusion of CWSN.

The school’s success story vividly illustrates the presence of strong leadership skills, which have contributed to its long-term sustainability. This leadership has kept parents, staff, and children motivated, while maximizing support for children with disabilities according to their abilities. The school leadership emphasizes the importance of giving recognition and visibility to children with special needs (CWSN). This specific principle is in line with Nancy Fraser’s theoretical framework, where she emphasizes the importance of the “3 R’s”; recognition, representation, and redistribution [52]. Fraser (2007) discusses the need for equal opportunities for all individuals, which can only be achieved if they are recognized, provided with the necessary resources, and adequately represented in society [52].

Several studies, both in Pakistan and globally, have highlighted issues with the policies and practices of inclusive education. Researchers stress the need for improved practices and the implementation of existing policies [54]. Winter (2020) analyzed educational policies and reports on inclusive education in Asian countries, revealing a common issue; the need for clear and consistent conceptions of inclusion, through national policies and local implementation [54]. This includes providing regular schools with the necessary infrastructure and teacher training to build skills and capabilities. Transforming segregated and integrated schools into inclusive ones will help nations develop inclusive societies that recognize and support the well-being, equality, independence, and full participation of people with disabilities, in all aspects of life [54]. Carrington et al. (2019) conducted a literature review of seven research papers on inclusive education in seven developing countries in the Asia Indo-Pacific region, including Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Kiribati, the Pacific Islands, Nepal, and Macao [55]. Their analysis identified six key themes:

- Flaws in developing and implementing inclusive education policy guidelines;

- Educational institutions that are ill-prepared to cater to children with special educational needs;

- Lack of resources, leading to deprivation and hindering the admission of children with special educational needs;

- Lack of collaboration among stakeholders, impeding progress toward inclusive education;

- Insufficiently trained teachers, resulting in a reluctance to include these learners;

- Curriculum deficiencies in teaching and learning strategies for children with special educational needs.

Immediate policy changes are necessary to advance the inclusion agenda [55]. Governments must involve classroom teachers in all phases of inclusive policy development and provide opportunities for professional development. This will help teachers contribute to sustainable development goals and promote inclusive settings in schools. Teachers expect support and professional development opportunities from school administrators, to enhance their self-efficacy, reduce stress, and improve teaching effectiveness [15].

6. Conclusions

The inclusive atmosphere at the Praxis School presents an opportunity to supportchildren with special educational needs (CWSN). It is crucial to recognize that CWSN require time and attention to acclimate to their surroundings. However, within the school’s inclusive environment, they feel a sense of ownership, inclusion, respect, and value from others, as demonstrated in the previous section. This sentiment aligns with the findings of Ryokkynen and Raudasoja (2022), who emphasized the importance of CWSN feeling they have ownership of their educational environment [56]. According to Kuutti et al. (2022), children with special educational needs who are in segregated settings encounter difficulties, such as limited socialization opportunities [5]. Socially stigmatized groups tend to have less clear social bonds, making them more sensitive to issues of socialization. Nonetheless, the Praxis School stands as a tangible success story, effectively confronting societal obstacles and offering clear guidance on how to surmount them, through awareness and acceptance.

7. Strengths and Limitations

The study possesses both strengths and limitations. Its strengths lie in its originality, being the first of its kind to specifically investigate factors contributing to the sustainability of inclusive education setups in the context of Pakistan. However, its limitations include a lack of generalizability due to its embedded single-case study design, based on qualitative research. While replication within the same context is feasible and recommended for future studies, applying these findings to other contexts may prove challenging, due to contextual disparities and variations in researchers’ perspectives. Another limitation of the study is that it relies solely on information gathered from educators. The results and conclusions would have been more robust if other stakeholders, such as parents, siblings, social workers, and community supporters, had been included to ensure their voices were heard. It is recommended that future studies incorporate these additional stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K.; data curation, M.K.; writing—M.K.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Fund of TU Berlin.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Following research standards in Pakistan, while securing approval from an ethics committee is crucial, having an explicit ethical code for the study is not a prevalent requirement. The study received approval from the Ethical Committee, with Dr. Razia Fakir, Head of the Ethical Committee at Iqra University, Karachi, Pakistan, endorsed the research. After completing the review board statement form, it was submitted to the research unit. The approval was obtained by the department on the 11 September 2021. After obtaining the approval the researchers proceeded with the data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained, confirming there is no harm or threat to members, and attempts were made to establish trustworthiness and faith between the investigator and members. Above all, members’ secrecy, privacy, and obscurity were assured through a letter. It is extremely significant to address that an ethical researcher kept inquiring about respondents’ esteem. This reduces harm and ethical behavior in all phases of the research work, even at the writing-up stage and afterwards. All transcripts were stored securely. All members of the study who signed the consent form were assured verbally that the researchers would not reveal their identity to anyone. It is important to mention here that before carrying out the research study, an ethics review form was filled in to sensitize and ensure issues related to respondents’ anonymity. The form was developed by the ethics review board of the university. The form addressed areas such as informed consent, confidentiality, and storage of data. Therefore, informed consent forms were signed by participants and all were handed over in the letter of information, with details of the objectives of the research study and its significance.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The researchers acknowledge the support from the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Fund of TU Berlin.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Diesendorf, M. Sustainability and sustainable development. In Sustainability: The Corporate Challenge of the 21st Century; Dunphy, D., Benveniste, J., Griffiths, A., Sutton, P., Eds.; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, Australia, 2000; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann, M. Learning to transform the world: Key competencies in Education for Sustainable Development. Issues Trends Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 39, 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Garrote, A.; Felder, F.; Krähenmann, H.; Schnepel, S.; Dessemontet, R.S.; Optiz, E.M. Social acceptance in inclusive classrooms: The role of teacher attitudes toward inclusion and classroom management. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 582873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, L.; Angharad, E.B. The social and human rights models of disability: Towards a complementarity thesis. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2021, 25, 348–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]