Abstract

With take-out food consumption rapidly increasing in China, understanding the factors influencing this dietary shift is crucial for public health, food security, and the environment. This study explores the role of health literacy in take-out food consumption, considering the mediating effects of food safety and environmental concerns and the moderating effect of perceived behavioral control. Cross-sectional survey data from 526 respondents were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis and regression to assess the relationships between health literacy, food safety concern, environmental concern, perceived behavioral control, and take-out food consumption frequency. The results revealed that health literacy is negatively associated with consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency; this relationship is completely mediated by food safety and environmental concerns. Furthermore, perceived behavioral control was found to strengthen the impact of food safety and environmental concerns on take-out food consumption frequency. This research advances the interdisciplinary understanding of health literacy’s impact on take-out food consumption by identifying its negative correlation and the mediating roles of food safety concern and environmental concern, with perceived behavioral control intensifying this relationship. Practical implications include the development of public health campaigns and food delivery platforms to strengthen supervision, and digital tools to empower consumers to make informed dietary choices.

1. Introduction

In the past few years, there has been a significant increase in take-out food consumption in China, reflecting a worldwide trend toward convenience-oriented dining. The “2022 China Food Delivery Industry Market Size and Development Trend Analysis Report” indicates that the Chinese catering and food delivery industry has experienced robust growth in recent years, with market sizes recorded at 785.58 billion yuan in 2021 and 941.7 billion yuan in 2022 [1,2]. Projections suggest that the industry will continue to expand, with an anticipated market size of 1.3319 trillion yuan by 2024 [3].

The surge in popularity of take-out food has certainly been a boon for the catering industry, but it comes with significant downsides. Concerns over food safety are paramount, as the intricate steps involved in preparing and delivering take-out pose risks for contamination and quality degradation [4]. Furthermore, the health implications cannot be overlooked; the typically high content of fats, salts, and additives in these meals can contribute to poor dietary habits and subsequent health issues if consumed habitually [5,6]. The environmental toll is also considerable, with many packaging materials used in take-out services exacerbating waste and ecological strain [7,8]. Therefore, this trend raises important questions regarding take-out food consumption determinants and implications for public health. The ubiquity of take-out food consumption in contemporary society epitomizes the complexities of modern lifestyles, with a myriad of determinants contributing to its prominence. Predominant among these is convenience, coupled with temporal limitations, which persists as a fundamental motivator for adopting take-out food practices [9,10]. Furthermore, economic factors influence consumer predispositions toward take-out food [11]. Economic analysis suggests that cost considerations may underlie the preference for take-out as an economic surrogate for traditional dining experiences. The rising tide of health consciousness has also been recognized as a pivotal determinant in consuming take-out food. For instance, An [12] delineated the impact of health awareness on consumer choices, driving a segment of the market towards healthier or more customized take-out offerings that align with specific nutritional objectives [12]. Environmental considerations have gained traction as a critical facet in the discourse surrounding take-out food, illuminating the ecological ramifications associated with take-out food, including the generation of packaging waste and the carbon footprint of food delivery [13,14]. Additionally, the perturbation of the gastronomic domain by pandemic-induced exigencies has precipitated a transformative effect on the modalities of take-out food consumption [15,16]. Lastly, the influence of social and demographic factors on take-out food consumption is noteworthy. Research conducted by Miura et al. [17,18] elucidated the impact of variables such as age, education, familial configurations, and urbanization on the propensity to utilize take-out services, with a correlation noted between these demographic elements and a heightened inclination towards convenience-oriented dietary patterns [17,18].

In essence, the integration of take-out food into the dietary regime of modern consumers is not a unidimensional phenomenon but rather the culmination of a confluence of factors. These encompass convenience and economic considerations and extend to health and environmental consciousness, adaptations due to pandemic-related disruptions, and the influence of various social and demographic indicators. These elements collectively constitute the intricate framework underpinning the dynamics of take-out food consumption within contemporary society.

Despite the extensive research on various factors influencing take-out food consumption, there is a notable gap in the literature concerning the role of health literacy. Among the myriad factors influencing dietary choices, health literacy emerges as a pivotal element, fundamentally shaping individuals’ food consumption patterns. While studies have explored the impact of general health awareness on dietary choices, there is limited research on how health literacy explicitly affects take-out food consumption.

To fill this gap, we focus on exploring the impact of health literacy on take-out food consumption. Health literacy refers to the comprehensive ability of individuals to have knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to health [19]. Improvements in health literacy can have a positive impact on people’s lifestyles and behaviors. Meanwhile, take-out food is widely considered to pose certain health risks [4,6]. Therefore, this study first explores the possible negative impact of consumer health literacy on take-out food consumption behavior. Specifically, we hypothesize that higher levels of health literacy may be associated with more informed and health-conscious decisions regarding take-out food consumption.

The impact of health literacy extends beyond individual choices; it encompasses a broader awareness of the environmental and food safety concerns associated with the production and consumption of food [4,13]. These concerns are particularly acute in China, where rapid urbanization and economic growth have led to significant environmental challenges and food safety incidents. As such, examining the mediating role of environmental and food safety concerns in the relationship between health literacy and take-out food consumption is of paramount importance. Thus, this study argues that if people are health-literate, they are more likely to have a clear understanding of food quality, food nutrients, food production, and the use of chemicals in processing food. With past research supporting that food and environmental concerns inhibit takeaway food orientation [20,21], it is safe to assume that health literacy, driven by consumer concerns for food and the environment (as mediators), may limit their takeaway food consumption.

Furthermore, research also reveals that people’s dietary behaviors are influenced by their perceived behavioral control, a construct derived from the theory of planned behavior [22]. Perceived behavioral control refers to an individual’s perception of their ability to perform a given behavior. Following the theory of planned behavior, we predict that behavioral control moderates the relationship between food safety concerns, environmental concerns, and takeaway food consumption. In other words, people who care more about the ecological ramifications of their food are more in control when engaging in takeaway food consumption. Thus, in the context of take-out food consumption, understanding how perceived behavioral control interacts with concerns about food safety and the environment is crucial for designing effective health interventions.

In short, this study aims to dissect the complex interplay between health literacy, environmental and food safety concerns, perceived behavioral control, and take-out food consumption in China. By identifying how these factors collectively shape dietary behaviors, we can better understand the mechanisms and inform public health strategies to promote healthier eating habits in a rapidly changing food landscape.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Health Literacy

Health literacy is defined as the degree to which individuals can attain, understand, and use health information as a basis for making correct health decisions and following treatment-related advice [23,24]. We expect that as individuals become more health literate, their propensity to consume take-out food diminishes. This premise is grounded in the health belief model [20,21], which theorizes that awareness and understanding of the health risks associated with certain behaviors, such as eating high-calorie take-out food, can lead to healthier choices.

Health literacy, which encompasses a person’s ability to understand, evaluate, and utilize health information [25], is integral to forming such beliefs and making informed dietary choices. A foundational study by Paakkari and Okan [26] found that individuals with lower health literacy levels may not have the relevant competencies to take care of their health [26]. This deficit can lead to difficulties in interpreting nutritional labels, recognizing the long-term health impacts of poor eating habits, and applying health recommendations in daily life, along with increasing take-out food consumption due to its convenience and accessibility [27]. This tendency towards convenient dietary options typically associated with higher calorie intake and lower nutritional value could be attributed to difficulties in understanding health information and its implications [28].

According to the health belief model, individuals with elevated levels of health literacy are likely to be cognizant of the potential health hazards associated with frequent intake of take-out food, such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, and are therefore more inclined to limit such behaviors [29]. Conversely, those with limited health literacy may not fully comprehend these dangers or the dietary strategies necessary to mitigate them. Consequently, enhancing health literacy levels could facilitate a greater internalization of the adverse health outcomes associated with regular consumption of take-out food, potentially leading to a reduction in the frequency of this behavior.

Based on the above discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Health literacy is negatively related to consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency.

2.2. Food Safety Concern

Food safety concern is characterized by the degree to which consumers experience anxiety about the composition of food, encompassing ingredients, methodologies of production, and the agricultural practices utilized [30]. The prevalence of food safety incidents has been positively correlated with an escalation in consumer apprehension regarding food safety matters [31]. In response to this growing concern, consumers are increasingly engaging in efforts to ascertain the levels and prevalence of various substances in food products, such as food additives, pesticide and insecticide residues, and artificial flavorings, in addition to gaining insights into the processing methods employed [32].

We propose that food safety concerns can be treated as a mediator to interpret the relationship between health literacy and take-out food consumption. Firstly, consumers with higher levels of health literacy are more likely to exhibit a heightened awareness of, and concern for, food safety issues. The health belief model [20,21] suggests that individuals with a greater understanding of health risks and their susceptibilities are more likely to take precautions to avoid negative health outcomes. Health literacy empowers individuals to comprehend and evaluate information related to food safety, such as contamination risks, proper food handling, and the identification of safe food sources [33]. Scholarly evidence underlines a positive link between health literacy and adopting health-protective actions, suggesting that individuals with greater health literacy levels are more proactive in safeguarding their health [28]. This evidence agrees that more knowledgeable individuals can better identify and respond to health risks, leading to increased vigilance in preventative practices. Thus, enhancing health literacy could promote public health by increasing food safety concerns and reducing the incidence of foodborne diseases.

Furthermore, as consumers become more apprehensive about the safety of their food, they are less likely to frequently consume take-out food, which is often perceived as less safe than home-cooked meals. Theoretically, the health belief model also suggests that individuals who perceive a higher risk (in this case, the potential for foodborne illness from take-out food) are more likely to engage in behaviors that they believe will reduce that risk (such as consuming less take-out food) [21]. Empirically, extant studies have found that food safety concerns are significantly associated with decreased consumption of certain high-risk foods [34]. Similarly, research by Onyango et al. [35] demonstrated that food safety concerns, particularly contamination, directly influence consumers’ food choices, leading to avoidance behaviors [35]. In sum, elevating food safety concerns will likely deter consumers from frequent take-out food consumption, favoring alternatives that they deem safer and more within their control.

Combining the above analyses, we hypothesize as follows:

H2.

Food safety concern mediates the effect of health literacy on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency, such that health literacy is positively related to food safety concern, and food safety concern has a negative impact on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency.

2.3. Environmental Concern

Environmental concern refers to the degree to which people are aware of problems regarding the environment and support efforts to solve them [36]. It reflects a psychological state encompassing beliefs, emotions, and behavioral intentions regarding the environment’s health and conservation [37]. We also propose that environmental concerns can mediate the relationship between health literacy and take-out food consumption.

On the one hand, consumers with a higher level of health literacy may exhibit greater awareness and, thus, concern for environmental issues. Firstly, health literacy empowers individuals to make informed decisions about their health and extrapolate them to the broader context of environmental health [38]. Additionally, the past literature indicates that health literacy encompasses the processing and understanding of health information and the competencies necessary for individuals to engage in actions to improve personal and public health [39]. This notion implies that individuals with higher health literacy may be more likely to recognize the connections between a healthy environment and personal health outcomes, thus fostering a greater concern for environmental issues [40].

On the other hand, the value-belief-norm theory posits that individuals’ actions are influenced by their fundamental values, which in turn shape specific beliefs and norms, leading to behavioral responses consistent with these values [41]. Therefore, consumers with strong pro-environmental values are likely to develop beliefs recognizing the adverse environmental consequences of excessive packaging and waste associated with take-out food. The literature supports a correlation between environmental concern and sustainable consumption behaviors [42]. Consumers who are environmentally concerned are more likely to engage in behaviors that reduce environmental harm, such as minimizing the use of single-use plastics often associated with take-out food [43]. Moreover, studies show that environmental awareness can change daily consumption patterns, particularly regarding food choices, favoring products and services with lower environmental impacts [44]. Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that heightened environmental concern would decrease the frequency of take-out food consumption as a part of a broader pattern of environmentally responsible behavior.

In light of the preceding discourse, we put forth the following hypothesis for consideration:

H3.

Environmental concern mediates the effect of health literacy on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency, such that health literacy is positively related to environmental concern, and environmental concern has a negative impact on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency.

2.4. Perceived Behavioral Control

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) represents people’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing a behavior of interest [45]. This construct reflects the degree to which an individual feels that the performance of the behavior is under their voluntary control [46]. Thus, consumer behavior depends on perceived limitations and ability, which significantly influence consumers’ intent to make a purchase [47].

The theory of planned behavior suggests that PBC—the belief in one’s ability to perform a behavior—can moderate the intention to engage in that behavior and its actual performance [45]. When applied to food safety concerns, PBC can be seen as a trigger that amplifies the likelihood that consumers’ worries about the safety of take-out food will decrease their consumption frequency. This phenomenon occurs because individuals who believe they have high control over their eating behaviors are more capable of acting on their concerns by selecting alternatives they deem safer, such as home-cooked meals [48]. The extant literature supports the contention that PBC can significantly moderate the relationship between concerns and behaviors. In studies examining the impact of health concerns on eating behavior, PBC has been found to play a pivotal role in determining whether those concerns translate into action [49]. Thus, PBC may serve as a critical factor that enables consumers to act following their safety concerns, thereby intensifying the negative relationship between these concerns and the frequency of take-out food consumption. Furthermore, if consumers are apprehensive about the safety of their food, and they believe they can choose safer alternatives, it is reasonable to expect a decline in behaviors they perceive as risky, such as frequenting take-out establishments. Therefore, the hypothesis predicts that with higher levels of PBC, the impact of food safety concerns on reducing take-out consumption frequency is expected to be stronger.

H4.

Perceived behavioral control strengthens the negative relationship between food safety concerns and consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency.

In the context of environmental concern, individuals with high levels of concern are likely to form negative attitudes towards behaviors that they perceive as harmful to the environment, such as frequent consumption of take-out food, which is often associated with excessive packaging waste and carbon footprint due to delivery [42]. Consumers with high PBC, who believe they have control over their eating behaviors, will be more inclined to reduce their take-out food consumption as a manifestation of their environmental concern. This relationship is further substantiated by the literature indicating that when individuals possess a high degree of PBC, they are more likely to translate their concerns into an actual behavior change, particularly in relation to environmentally friendly practices [50]. Empirical studies have shown that PBC can significantly moderate the impact of environmental concerns on consumer behavior, suggesting that individuals who perceive greater control over their actions are more responsive to their environmental concerns in making consumption choices [51].

Therefore, high PBC is expected to strengthen the resolve of environmentally concerned consumers to decrease take-out food consumption as part of their effort to mitigate negative environmental impacts.

From this, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H5.

Perceived behavioral control strengthens the negative relationship between environmental concern and consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency.

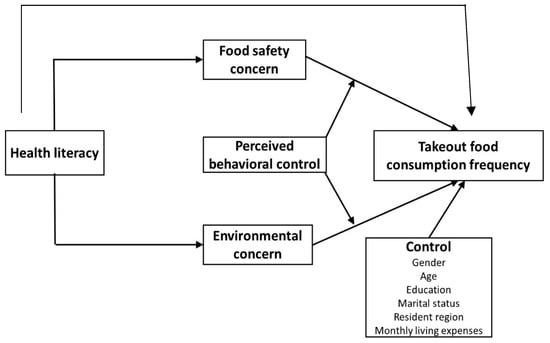

2.5. Conceptual Framework

Figure 1 below presents the conceptual framework of how the health literacy of an individual may affect take-out food consumption behavior. The model further incorporates food safety and environmental concerns as mediating intermediary mechanisms, enabling a health-literate consumer to avoid take-out food. Theoretically, the model considers that perceived behavioral control is derived from the theory of planned behavior as a moderator. We drew inspiration for the model from the psychology and behavior literature, which explains that possible negative relationships between food safety concerns, environmental concerns, and take-out food consumption can be enhanced by a higher level of perceived behavioral control [52,53].

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source

This study utilized an online survey for data collection, even though such an approach may result in social desirability and response bias. We used Podsakoff et al.’s [54] procedural remedies and the Harman single-factor test to control for such biases. Online data collection is more convenient, unobtrusive, and economical than paper-based surveys. The survey was disseminated via a website (www.wjx.cn), which is the largest professional questionnaire platform in China. As of January 1, 2024, this platform has published over 250 million questionnaires and collected nearly 20 billion responses. The questionnaire encompassed various elements, such as demographic information, behaviors related to take-out food consumption, food safety concerns, environmental concerns, perceived behavioral control, and health literacy.

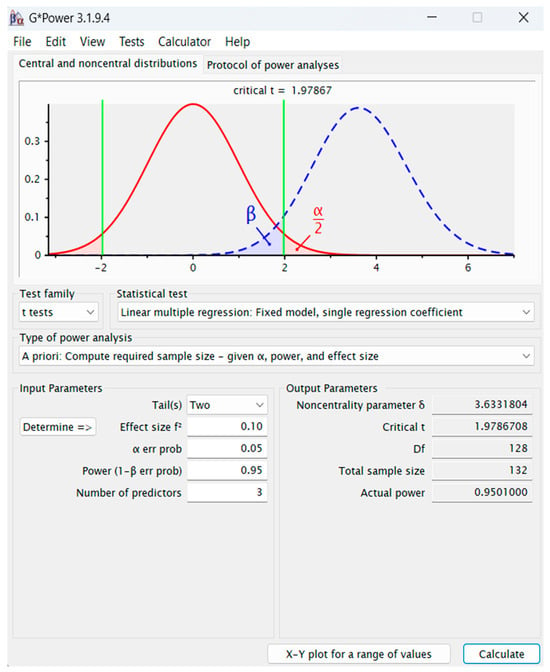

The sample size of this study was determined using Faul [55] latest version of (v.3.1.9.4). Using an alpha value of 0.05, a power of 0.95, an effect size of 0.15, and three predictors, the required sample size for this study was found to be 132 as shown in Figure 2. We used a convenience sampling technique for data collection because of its cost-effectiveness and time benefits, i.e., less time-consuming.

Figure 2.

Gpower software result.

To examine the effect of health literacy on take-out food consumption, we targeted individuals who had purchased take-out food in the past month. A screening question was integrated into the questionnaire to ensure appropriate participant selection.

During the questionnaire distribution process, we organized for four undergraduate students from four provinces, namely Fujian, Guangxi, Henan, and Shanxi (the first two are southern provinces, and the latter two are northern provinces in China), to distribute the questionnaires. They each contacted relatives and friends from their own provinces and invited them to fill in the questionnaire. We issued 600 questionnaires in total. Of these, 59 respondents indicated that they had not bought any take-out food in the last month, and 15 questionnaires were filled out incorrectly or incompletely. Consequently, the final tally of valid questionnaires amounted to 526. The data were collected across a period of six months, from January 28 to 30 June 2023. The demographics of respondents are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics.

3.2. Measure

Initially, the questionnaire was developed in English. To maintain the integrity of the concepts, it was translated into Chinese, followed by two independent rounds of back-translation by different translators. Any discrepancies were collaboratively examined and resolved through discussion between the research team and the translators until a consensus was achieved. Unless specifically indicated, we measured all the items using a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”, 5 = “strongly agree”). The scales for measurement were derived from existing scholarly works in the following manner:

The original scale of health literacy (HL) was adapted from Chinn and McCarthy [56]. To meet the requirements of our study, we modified the original scale to a five-point Likert scale format and rephrased the questions from interrogative to declarative statements. This approach allowed the response options to span a spectrum from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Following the initial draft, we enlisted the expertise of two undergraduate students specializing in public health to examine the items independently. Taking their feedback into account, we made minor adjustments to the items and continued the iterative review and modification process. This procedure was repeated until there was a consensus between the two student reviewers. Once their assessments aligned, we established the final version of the scale.

The process outlined above resulted in the creation of a 10-item Likert scale designed to measure health literacy (HL1: I am able to obtain help readily when needed; HL2: I provide all the necessary information to a doctor or nurse to assist in my care; HL3: I inquire about all the information I need when speaking with a doctor or nurse; HL4: I ensure that a doctor or nurse clarifies anything I do not understand; HL5: I actively seek out a variety of information regarding my health; HL6: I frequently consider whether health information is applicable to my particular situation; HL7: I often assess the credibility of the health information I receive; HL8: I am inclined to challenge my doctor or nurse’s advice with findings from my own research; HL9: I believe there are ample opportunities to influence government health policies; and HL10: In the past year, I have taken action on a health issue).

Food safety concern (FSC) was adapted from Iqbal et al. [57], comprising four items (FSC1: I am very concerned about the amount of artificial additives and preservatives in foods; FSC2: The quality and safety of food nowadays concern me; FSC3: I am concerned about food processing; and FSC4: I am concerned that the social order of food processing is protected).

The environmental concern (EC) scale was provided by Koenig-Lewis et al. [58], encompassing a total of five items (EC1: I think we are not doing enough to save scarce natural resources from being used up; EC2: Natural resources must be preserved even if people must do without some products; EC3: Much more fuss is being made about air and water pollution than is justified; EC4: I feel angry and frustrated when I think about the harm being done to plant and animal life by pollution; and EC5: I think the government should devote more money toward supporting conservation and environmental programs).

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) was adapted from Teixeira et al. [53], with the words “organic food” modified to “take-out food” to fit the context of our study. The scale comprised three items (PBC1: To buy or not to buy take-out food is entirely up to me; PBC2: I am confident that if I want, I can buy take-out food; and PBC3: I have resources and time to buy take-out food).

The dependent variable, take-out food consumption frequency (TFCF), was operationalized as the number of take-out food purchases in the past week. In the questionnaire, we first asked the respondents to open their most frequently and commonly used take-out platform application (i.e., Meituan Take-out, Are You Hungry, or both), check the number of take-out orders they had in the past week, and then recorded this number.

The survey additionally gathered data on the socio-demographic profiles of the participants to facilitate the depiction of the sample group. These socio-demographic factors encompassed gender, age, education, marital status, place of residence, and monthly living expenses. All of these elements were considered control variables in the later stages of the empirical analysis. It is important to note that these socio-demographic factors had to be converted into dummy variables before they were incorporated into the regression analysis.

3.3. Common Method Bias

The questionnaire in this study was filled out by one person at a particular time, which may have introduced common method bias to the data [54]. This study employed preventive and post-examination measures to mitigate the impact of common method bias.

In terms of preventive measures, the questionnaire strategically arranged the items. The dependent variable, related to take-out food consumption, was placed at the beginning. The items associated with the mediating variables (food safety concern and environmental concern) were positioned in the middle, while the items related to the independent variable (health literacy) were placed at the end. This arrangement helped prevent respondents from making unwarranted associations or speculations about causality. In addition, we used procedural remedies by Podsakoff et al. [54] to avoid the possibility of common method bias. For instance, we ensured respondents’ anonymity and confidentiality, provided instructions about the purpose of the study, and filled out the survey. These measures helped to reduce common method bias [54].

For post-examination measures, this study used the Harman single-factor test to assess the influence of common method bias. Exploratory factor analysis revealed that the variance explained by the first factor was 38.28%, which was less than 50%. These results suggest that no single factor was able to account for most of the variability, indicating that the influence of common method bias was not severe [54].

3.4. Reliability and Validity

Cronbach’s α coefficient was employed to test construct reliability. As shown in Table 2, the reliability of all constructs (including health literacy, food safety concern, environmental concern, and perceived behavioral control) was greater than 0.7, which means that all of the constructs in this study had good reliability.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity assessment.

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to assess the construct validity of all four constructs in our study. The confirmatory factor model output represented a good fit with the data (χ2 = 402.708, DF = 203, CFI = 0.934, TLI = 0.925, RESEA = 0.080). We calculated the composite reliability and average variance extracted (also presented in Table 2). The findings indicated that all of the composite reliabilities, ranging from 0.809 to 0.945, surpassed the 0.70 benchmark. Additionally, all of the average variances extracted, ranging from 0.586 to 0.766, exceeded the 0.50 cutoff. Consequently, these four metrics affirmed satisfactory convergent validity [59].

We assessed the shared variance among all possible pairs of constructs to determine if they were lower than the average variance extracted for the individual constructs. For every construct, the square root of the average variance extracted surpassed its maximum correlation with other constructs, offering evidence of discriminant validity [59]. Collectively, these findings affirmed the sufficient reliability and validity of the measures in our study. Consequently, in the forthcoming regression analysis, we use the mean value of the items measuring each construct as the representative value.

3.5. Empirical Model

The hypotheses involved in this study were tested through the following five empirical models.

Among them, Model 1 was employed to evaluate Hypothesis H1. Hypothesis H2 was tested using a combination of Model 1, Model 2, and Model 4. Hypothesis H3 was examined through an analysis involving Model 1, Model 3, and Model 4. Lastly, Hypothesis H4 and H5 were assessed with the application of Model 5.

3.6. Hypothesis Testing

Regression analysis was employed to evaluate the research hypotheses. Table 3 presents the outcomes of this analysis for the five empirical models. Within these models, as detailed in Table 3, we accounted for health literacy as the primary independent variable. Furthermore, we incorporated control variables, including gender, age, education, marital status, place of residence, and monthly living expenses, to mitigate the potential influence of confounding factors.

Table 3.

The results of regression analysis.

In Model 1 of Table 3, health literacy is shown to have a significant negative impact on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency (β_11 = −0.960, p < 0.05), providing support for the research Hypothesis H1.

Hypotheses H2 and H3 suggest that food safety and environmental concerns mediate the relationship between health literacy and consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency. Initially, we applied the three-step approach to examine the mediating effects [60], followed by using Hayes’ process model for confirmation [61].

Referencing Table 3, Model 2 shows a significant positive relationship between health literacy and consumers’ food safety concerns (β_21 = 0.861, p < 0.05), and Model 4 demonstrates that food safety concern has a significant negative effect on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency (β_42 = −0.555, p < 0.05). Integrating findings from Models 1, 2, and 4 and employing the Baron and Kenny method [56] to assess mediation, we found that food safety concern significantly mediates the influence of health literacy on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency. Thus, Hypothesis H2 was supported.

Similarly, Model 3 in Table 3 indicates a significant positive link between health literacy and environmental concern (β_31 = 0.818, p < 0.05), while Model 4 shows that environmental concern significantly reduces consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency (β_43 = 0.551, p < 0.05). Upon merging the results from Models 1, 3, and 4 and applying the Baron and Kenny method [60], it became evident that environmental concern also significantly mediates between health literacy and consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency, thus supporting Hypothesis H3.

Notably, since the regression coefficient of health literacy in Model 4 is no longer significant (β_41 = −0.032, p > 0.1), the direct effect of health literacy on take-out food consumption frequency disappears when the mediating factors of food safety and environmental concerns are included. Therefore, food safety and environmental concerns jointly fully mediate the impact of health literacy on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency.

Following the initial analysis, we employed Hayes’ Process macro to reassess previously discussed mediating relationships [61]. The Process tool assesses the significance of a mediation effect by analyzing whether the 95% confidence interval for the indirect impact excludes zero. The mediation effect is considered significant if zero is not within the confidence interval. The outcomes from 5000 bootstrap samples using the Process tool are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Bootstrap mediating test results.

According to Table 4, the indirect effect’s path coefficient for food safety concerns is −0.545, with a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval CI of [−0.845, −0.307]. Since zero is not within this interval, the mediation effect of food safety concerns is statistically significant. The indirect effect’s path coefficient for environmental concern is −0.545, with a 95% bias-corrected CI of [−0.861, −0.233]. As this interval also excludes zero, the mediation effect of environmental concern is confirmed to be significant. Furthermore, with the inclusion of the mediating variable, the direct effect path coefficient of health literacy is −0.019, with a 95% bias-corrected CI of [−0.211, 0.429]. This interval includes zero, indicating that the direct effect is not significant. These findings align perfectly with those obtained using the Baron and Kenny approach to assess mediation. Thus, this study concludes that food safety and environmental concerns fully mediate health literacy’s influence on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency. In sum, both Hypotheses H2 and H3 received support.

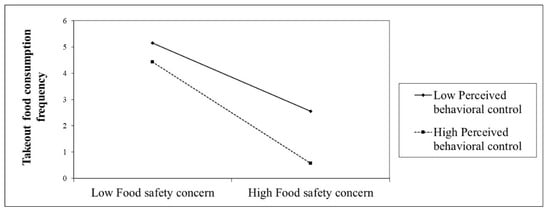

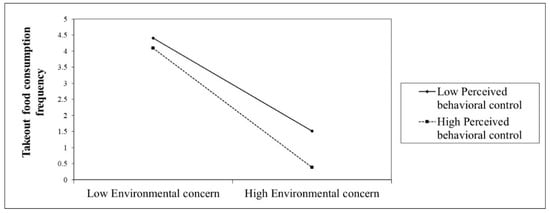

Hypothesis H4 and H5 proposed that perceived behavioral control strengthens the negative impact of food safety and environmental concerns on consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency, respectively. As shown in Model 5 of Table 3, perceived behavioral control negatively moderates the effect of food safety concerns on consumers’ take-out food consumption (β_55 = −0.352, p < 0.05), thus supporting Hypothesis H4. Similarly, perceived behavioral control also strengthens the negative impact of environmental concern on consumers’ take-out food consumption (β_56 = −0.244, p < 0.1, marginally significant), thereby supporting Hypothesis H5.

To determine the nature of the above interactions, we graphed the relationship between food safety concern, environmental concern, and take-out food consumption frequency in size at high and low levels of perceived behavioral control (plus and minus one standard deviation from its means) to illustrate these complex moderating effects. These graphical representations are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Specifically, Figure 3 indicates that as food safety concerns increase, take-out food consumption frequency drops more sharply for individuals with higher perceived behavioral control. This finding provides support for Hypothesis H4. Similarly, Figure 4 demonstrates that take-out food consumption frequency diminishes more rapidly with environmental concern with higher perceived behavioral control. This latter finding also provides support for Hypothesis H5.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of perceived behavioral control on the relationship between food safety concern and take-out food consumption frequency.

Figure 4.

The moderating effect of perceived behavioral control on the relationship between environmental concern and take-out food consumption frequency.

3.7. Robustness

Since the dependent variable-consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency in Models 1, 4, and 5 can be considered a count variable, we used Poisson regression to re-estimate these models. The findings are presented in Table 5 (to conserve space in the table, the analytical results for control variables are not shown in Table 5). Examination of Table 5 reveals that the direction and statistical significance of the regression coefficients for all key variables remained consistent. Therefore, the empirical results of this study are robust.

Table 5.

The results of Poisson regression analysis.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the determinants of Chinese consumers’ take-out food consumption. The findings of this study revealed that health literacy is negatively related to the frequency of consumers consuming take-out food. Additionally, we found that food safety and environmental concerns mediate the relationship between consumer health literacy and take-out food consumption frequency. Moreover, perceived behavioral control was a moderating variable in the relationships between the two mediators, food safety concern and environmental concern, and consumers’ take-out food consumption frequency.

The results of this research broaden our understanding of consumer purchase behaviors related to take-out food by crafting and validating a detailed model that incorporates moderation and mediation. This study furnishes foundational insights and corroborative data regarding the negative factors influencing consumers’ intention to buy take-out food. Our research augments existing scholarly work on the connections between consumer health consciousness and organic food purchase [57,62], the effects of food quality and safety on food choice (domestic vs. imported) [63], as well as the impact of environmental considerations on sustainable food choices [64] within various other settings. Hence, this study enhances the literature by investigating the negative determinants in the burgeoning take-out food sector. The finding that environmental concern mediates the relationship between health literacy and food consumption is in line with the work of Wang et al. [65], arguing that environmental concern acts as a significant mediating variable between individual belief and engagement in healthy activities. The findings also corroborate prior assertions (cf. Marcelino et al. [66]) that environmental concern mediates the impact of environmental responsibility on green consumption intention. Regarding the mediating role of food concern, this study resonates with the viewpoint of Li et al. [67]: that people’s belief in health mediates the impact of health literacy on their health-related behavior. Beyond the above, this work adds to the present body of knowledge by examining behavioral control as a moderator of the relationship between food concern and environmental concern and people’s behavior to discourage takeaway food consumption. This finding aligns with the theory of planned behavior, positing that people’s ability to control their behaviors is more likely to prevent unhealthy food consumption.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

First and foremost, health literacy is a concept from the medical and health field [68]. In examining its influence on the consumption of take-out food, this concept is merged with insights from public health, consumer behavior, psychology, and various other fields, establishing it as a multidisciplinary study area. To our knowledge, the precise theoretical framework detailing how health literacy impacts take-out food consumption remains unclear. This research intends to shed light on the mediating and moderating factors through which health literacy can affect take-out food consumption habits to advance the scholarly understanding of take-out food consumption patterns and research.

Secondly, our study provides a novel contribution to the health belief model (HBM) by incorporating health literacy as a determinant of health-related behavior, specifically in the context of take-out food consumption. The HBM, developed to explain the failure of people participating in programs to prevent and detect disease [20], posits that personal beliefs about health conditions influence health behaviors. By establishing a negative correlation between health literacy and take-out food consumption, we suggest that individuals with higher health literacy are likely to perceive greater severity and susceptibility to health risks associated with frequent take-out food consumption, thus aligning with the model’s constructs of perceived threat [21].

Moreover, the mediating role of food safety and environmental concerns indicates the layered process through which health literacy influences consumer behavior, aligning with the ideas presented by Wong et al. [69], who discussed the complexity of cognitive factors as mediators in health decision-making processes. The present study extends this understanding to the context of take-out food consumption, providing evidence that these concerns are key pathways through which health literacy can shape dietary choices.

The moderating effect of perceived behavioral control on the relationship between food safety concerns, environmental concerns, and take-out food consumption frequency resonates with the principles of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [45]. This study adds empirical weight to the TPB by demonstrating how perceived control can influence the strength of the mediating effects of attitudes and concerns on behavior. It suggests that interventions aiming to change behavior should consider enhancing individuals’ confidence in their ability to execute the desired behavior.

Finally, one of the most significant contributions of this study is the integration of multidisciplinary variables (i.e., from health sciences, environment, food, and people’s food behavior) into a single study to provide fresh insights concerning the importance of health, food literacy, and environmental awareness in shaping individual behaviors. This interdisciplinary perspective of the current work bridges the gaps between various subjects, offering a more holistic understanding of human behavior. In addition, this study also adds to the current discourse by specifying that people’s health-related knowledge enhances their concern about food and its ingredients.

4.2. Practical Implications

First, given that health literacy is negatively associated with the frequency of take-out food consumption, public health campaigns should aim to improve health literacy among consumers. By providing clear and accessible information about the benefits of a balanced diet and the potential risks of frequent take-out consumption, consumers may be encouraged to make healthier eating choices. Moreover, educational institutions can incorporate health literacy into their curricula, focusing on the impact of dietary choices on personal health, food safety, and the environment. They should create modules explaining how to interpret nutritional information on menus and food labels, thus enabling consumers to make more informed decisions.

Second, food service providers can leverage this insight to cater to health-literate consumers by highlighting the safety and environmental impact of their food. They should emphasize clean cooking processes, sustainable packaging, and sourcing ingredients from environmentally responsible suppliers. Furthermore, marketing efforts by take-out businesses could focus on the health aspects of their offerings. By promoting items with better nutritional profiles and eco-friendly packaging, businesses can appeal to consumers’ food safety and environmental concerns, potentially attracting a more health-conscious customer base.

Third, by examining the mediating role of environmental and food concerns, our study offers new data on how health interventions, health-related policy decisions, and consumer education can shape perspectives on environmental and food quality, discouraging the consumption of takeaway food and enhancing healthy dietary habits. Our study findings imply that health literacy prevents unhealthy food use and enhances people’s concerns about the environment and quality food consumption.

Fourth, take-out food platforms must actively meet their legal responsibilities, harmonizing their commercial profit objectives with the imperative of safeguarding consumer food safety. They should willingly take on the duty to mitigate and manage the risks associated with online catering services. By establishing platform regulations, such as entry audits, the application of credit rating systems, and the creation of reward and penalty frameworks for take-out vendors, it is possible to oversee vendor operations comprehensively and enhance the oversight and governance of take-out food safety.

Fifth, interventions aimed at increasing perceived behavioral control could be developed. These might include tools or apps that help consumers track and control their take-out food consumption, thus reinforcing their ability to make healthier choices despite their busy lifestyles. Take-out food businesses can partner with health organizations to create endorsements or certifications for menus that meet certain health criteria, guiding consumers toward healthier options and reducing the frequency of unhealthy take-out food consumption.

Finally, the integration of variables from multiple fields, such as psychology, public health, environment, and human behavior, provides guidelines for policymakers on how cooperation among various stakeholders can encourage the use of healthy food and protection of the environment, as well as creating awareness among the public regarding food quality and consumption. This model suggests that holistic management among various fields may create synergy and cooperation to protect the environment and reduce public expenditure on unhealthy food.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While providing valuable insights into the interplay between health literacy and take-out food consumption, this study has limitations. One such limitation is the cross-sectional design, which, although useful for identifying associations, does not allow for the establishment of causality. Future research would benefit from a longitudinal approach to better understand the directionality of these relationships over time [70].

Another limitation concerns the self-reported measures used to assess health literacy and food consumption frequency. These measures are subject to social desirability and recall biases, which may affect the accuracy of the reported data [71,72]. To mitigate the limitations associated with self-reporting, future studies could incorporate objective measures of health literacy and take-out food consumption, such as sales data or third-party assessments of health literacy levels.

The mediating roles of food safety and environmental concerns were established, yet this study did not explore other potential mediators, such as nutritional knowledge or socio-economic factors. These factors could also play significant roles in the relationship between health literacy and take-out food consumption, and warrant examination.

Lastly, exploring intervention studies to enhance health literacy and perceived behavioral control could offer actionable insights into effective strategies for promoting healthier take-out food choices among consumers.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights a negative correlation between health literacy and take-out food consumption frequency, suggesting that more health-literate individuals consume take-out less frequently. Mediating this relationship, food safety concerns and environmental concerns are influential factors, reflecting a deeper awareness among those with higher health literacy. Additionally, perceived behavioral control moderates how these concerns affect take-out consumption; greater perceived control intensifies the impact of these mediators.

Our findings can inform public health strategies, implying that health literacy interventions could reduce take-out food consumption by addressing food safety and environmental concerns. This could lead to better health outcomes and more sustainable consumer behaviors. This study underscores the need for educational initiatives that enhance informed dietary decisions and suggests a multi-faceted approach to public health interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; data curation, X.Z. and L.L.; formal analysis, L.L.; methodology, M.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L. and X.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.A.M. and M.A.K.; supervision, L.L.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Social Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (Grant No. FJ2023B113), Scientific Research Foundation of Fujian University of Technology, China (Grant No. GY-S21036).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained via email by contacting lmlin@fjut.edu.cn.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Nengpei, M. Analysis of China’s Online Food Delivery Industry in 2022: Industry Scale is Expanding Steadily and the Market is Accelerating Sinking. Available online: https://www.huaon.com/channel/trend/904313.html (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- By Allowing More People to “Eat at Home”, This Company’s Revenue Will Reach 7.1 Billion in 2022. Available online: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_22639546 (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Analysis of Market Size and Development Trends of China’s Food Delivery Industry in 2022. Available online: https://www.sgpjbg.com/info/31794.html (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Boyce, J.; Broz, C.C.; Binkley, M. Consumer perspectives: Take-out packaging and food safety. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworowska, A.; Blackham, T.; Davies, I.G.; Stevenson, L. Nutritional challenges and health implications of takeaway and fast food. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Cheng, J.; An, D.; He, Y.; Tang, Z. Occurrence, potential release and health risks of heavy metals in popular take-out food containers from China. Environ. Res. 2022, 206, 112265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Schmid, A.; Mendoza, J.M.F.; Azapagic, A. Environmental impacts of takeaway food containers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xue, L.; Jiang, Y.; Song, M.; Wei, D.; Liu, G. Food delivery waste in Wuhan, China: Patterns, drivers, and implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 177, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, H.G.; Davies, I.G.; Richardson, L.D.; Stevenson, L. Determinants of takeaway and fast food consumption: A narrative review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2018, 31, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.Z. Social impact of “take-out fast food” from the perspective of sociology. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2023, 5, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, J.K. The effect of demographic, economic, and nutrition factors on the frequency of food away from home. J. Consum. Aff. 2006, 40, 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R. Fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption and daily energy and nutrient intakes in us adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wu, L.; Peng, J.; Chiu, C.-H. Research on environmental issue and sustainable consumption of online take-out food—Practice and enlightenment based on China’s Meituan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, Z. Mapping the environmental impacts and policy effectiveness of takeaway food industry in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 152023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Choi, H.H.; Choi, E.-K.C.; Joung, H.-W.D. Factors affecting customer intention to use online food delivery services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Shen, S.; Ramírez García, J.A.; Shi, C. Partner with a third-party delivery service or not? A prediction-and-decision tool for restaurants facing take-out demand surges during a pandemic. Serv. Sci. 2022, 14, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G. Socio-economic differences in takeaway food consumption and their contribution to inequalities in dietary intakes. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G. Socio-economic differences in takeaway food consumption among adults. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Ju, X.M.; Zhang, X. What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Wolf, M.S. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007, 31, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobinac, A. Access to healthcare and health literacy in Croatia: Empirical investigation. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; Lloyd, J.E. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.; Okan, O. COVID-19: Health literacy is an underestimated problem. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e249–e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.H.; Gazmararian, J.; Parker, R.M. The impact of low health literacy on the medical costs of medicare managed care enrollees. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, H.; Shah, S.; Gafor, H.; Mahmood, M.; Ghazi, H.F. Usage of health belief model (HBM) in health behavior: A systematic review. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2020, 16, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L.M. The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Lin, T.T. Triple bottom line model and food safety in organic food and conventional food in affecting perceived value and purchase intentions. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureña, F.; Bernabéu, R.; Olmeda, M. Women, men and organic food: Differences in their attitudes and willingness to pay. A spanish case study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite 2014, 76, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, J.; Trübswasser, U.; Pradeilles, R.; Le Port, A.; Landais, E.; Talsma, E.F.; Lundy, M.; Béné, C.; Bricas, N.; Laar, A.; et al. How do food safety concerns affect consumer behaviors and diets in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 32, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, B.M.; Hallman, W.K.; Bellows, A.C. Purchasing organic food in us food systems: A study of attitudes and practice. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Jones, R.E. Environmental concern: Conceptual and measurement issues. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Michelson, R.E.D.a.W., Ed.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2002; pp. 482–524. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W. The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.A.; Bess, K.D.; Tucker, H.A.; Boyd, D.L.; Tuchman, A.M.; Wallston, K.A. Public health literacy defined. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtomo, S.; Ohnuma, S. Psychological interventional approach for reduce resource consumption: Reducing plastic bag usage at supermarkets. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavite, H.J.; Mankeb, P.; Suwanmaneepong, S. Community enterprise consumers’ intention to purchase organic rice in Thailand: The moderating role of product traceability knowledge. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1124–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, A.E.; Mazzocchi, M.; Traill, W. Modelling risk perception and trust in food safety information within the theory of planned behaviour. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wölfing, S.; Fuhrer, U. Environmental attitude and ecological behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Cheung, M.W.L.; Ajzen, I.; Hamilton, K. Perceived behavioral control moderating effects in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.F.; Barbosa, B.; Cunha, H.; Oliveira, Z. Exploring the antecedents of organic food purchase intention: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, S.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Faul, F. A short tutorial of GPower. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, D.; Mccarthy, C. All aspects of health literacy scale (AAHLS): Developing a tool to measure functional, communicative and critical health literacy in primary healthcare settings. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 90, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Yu, D.; Zubair, M.; Rasheed, M.I.; Khizar, H.M.U.; Imran, M. Health consciousness, food safety concern, and consumer purchase intentions toward organic food: The role of consumer involvement and ecological motives. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211015727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig-Lewis, N.; Palmer, A.; Dermody, J.; Urbye, A. Consumers’ evaluations of ecological packaging—Rational and emotional approaches. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Parashar, S.; Singh, S.; Sood, G. Examining the role of health consciousness, environmental awareness and intention on purchase of organic food: A moderated model of attitude. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R.; Imami, D.; Miftari, I.; Ymeri, P.; Grunert, K.G.; Meixner, O. Consumer perception of food quality and safety in western balkan countries: Evidence from Albania and Kosovo. Foods 2021, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, P.; Begho, T. Paying for sustainable food choices: The role of environmental considerations in consumer valuation of insect-based foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 106, 104816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Mo, T.; Wang, Y. Better self and better us: Exploring the individual and collective motivations for China’s Generation Z consumers to reduce plastic pollution. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, D.; Widodo, T. Consumer Environment Responsibility and Concern on Green Consumption: Unavailability of Eco-Product Moderation. Trikonomika 2021, 20, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, P. Factors influencing the health behavior during public health emergency: A case study on norovirus outbreak in a university. Data Inf. Manag. 2021, 5, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Davis, T.C.; McCormack, L. Health literacy: What is it? J. Health Commun. 2010, 15, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Leslie, J.J.; Soon, J.A.; Norman, W.V. Measuring interprofessional competencies and attitudes among health professional students creating family planning virtual patient cases. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plano Clark, V.L.; Anderson, N.; Wertz, J.A.; Zhou, Y.; Schumacher, K.; Miaskowski, C. Conceptualizing longitudinal mixed methods designs: A methodological review of health sciences research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2015, 9, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, L.; Bristowe, K.; Ellis-Smith, C.; Aworinde, J.; Fraser, L.K.; Downing, J.; Bluebond-Langner, M.; Chambers, L.; Murtagh, F.; Harding, R. Enhancing validity, reliability and participation in self-reported health outcome measurement for children and young people: A systematic review of recall period, response scale format, and administration modality. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1803–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.S.; Talib, N.; Alam, M.M.; Su’ud, M.M.; Khan, S. Intention to Get the (COVID)-19 Vaccine and Religiosity: The Moderating Role of Knowledge About the (COVID)-19 Vaccine. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2023, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).