Abstract

In recent years the world has seen an increase in the popularity of farmer’s markets, short food supply chains and local food systems. This growth can be attributed to the public’s growing consciousness of the impracticality of the global food system, globalization’s waste of fossil fuels, the fear of food chemicals, and small farmers’ desire to directly sell their products, among other things. Although there are a wealth of farmer’s market surveys and research on this topic that has been conducted over the past decades around the world, scant data have been collected about farmer’s markets in the south of Spain. This study focuses on the organic farmer’s market in Granada (Spain) and consists of five surveys developed in 8 years which are analyzed to help better understand this market that was first established in the Spring of 2013. It will also consider research on farmer’s markets in Europe and beyond in order to compare the situation of the Granada market as well as bringing in some new ideas of how it can be improved.

1. Introduction

The current globalized and hegemonic agri-food system is made up of a group of large multinational companies that centralize and determine its functioning and structure [1]. This concentration of power causes changes in production systems that are increasingly oriented towards large agribusiness exports and modifies consumption habits, characterized by low prices and lower product quality [2]. Due to its large purchasing power, large-scale distribution puts pressure on suppliers and producers to lower prices, giving rise to unfair production and commercial practices [3].

Consumers have shown to present a growing mistrust of the food sold in these establishments, as they are not associated with the idea of “eating well” (eating healthy, risk-free, pesticide-free, GM-free, varied, etc.) [4].

In addition to this, after decades of growing globalization, cheap exporting and importing of goods, and a global system of economic superpowers exploiting poorer countries for cheap work and products [5], many people have been demanding a new system of commercialization that focuses on green, fair, and local products [6]. The average food product in the Spanish state has traveled 6.158,95 km before reaching the consumer, illustrating a huge inefficiency in the globalized food system which unnecessarily wastes fossil fuels, increases the need for preservative chemicals in our foods, and damages local economies [7,8,9].

This food-related disaffection has led people to act individually or collectively to seek alternatives, which are generally framed in what have been called short food supply chains (SFSCs). The EU Rural Development Regulation 1305/2013 defines short food supply chains as “a supply chain involving a limited number of economic operators, committed to cooperation, local economic development, and close geographical and social relations between food producers, processors, and consumers”. This recognizes the potential role of short food supply chains in re-localizing agricultural production (for example, by supporting local farmers) and, more broadly, in improving social cohesion at a local–regional scale. The EIP-Agri Focus Group (final report 2015) defines short food supply chains as a means to “restructure food chains in order to support sustainable and healthy farming methods, generate resilient farm-based livelihoods (in rural, peri-urban and urban areas) and re-localize the control of food economies” [10].

Short food supply chains favor relations of proximity and trust between local producers, retailers, restaurants, and consumers with the aim of ensuring food safety, food sovereignty, environmental sustainability, social capital, and economic efficiency [11]. Among other objectives, short food supply chains also support the recovery of economic, social, and geographical links between food products and rural knowledge, local varieties, local culture, as well as the agroecological and climatic conditions of bioregions [12]. A comprehensive definition of short food supply chains highlights not only just economic and social impacts but also addresses environmental and ethical problems from a bioregional perspective. In this sense, they become a real strategy for achieving truly resilient food systems [6].

One of the most typical short supply chains are farmer’s markets, where direct selling is carried out in organized sale outlets, which are selling points managed either individually or collectively [13]. The definition provided by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service states that a farmer’s market is a place where “two or more farmer-producers sell their own agricultural products directly to the general public at a fixed location, which includes fruit and vegetables, meat, fish, poultry, dairy products, and grains” [14]. This definition can be applied to farmer’s markets across the world, due to its generality in location and products that make them stand out from supermarkets and neighborhood stores.

The frequency of farmer’s markets ranges from weekly to monthly, and their functioning is similar to that of a traditional street market before they were transformed and supplied by large warehouses with products from all over the world, losing the essence and support for local farmers [15].

In this sense, they have particular conditions in terms of access, sales, and the origin and mode of production of the products, which are local and sometimes also organic and/or artisanal. Local producers can sell their products directly or through their organizations, without any secondary agents, and sometimes they are even self-managed by the producers and/or consumers who promote them [13].

The north and east of Spain have always had traditional markets for local products that could be considered as farmer’s markets. In the south and in larger metropolitan areas where supermarkets are particularly well established, farmer’s markets have had to be created as the traditional open-air markets are no longer related to farmers but to cheap products coming from big retailers and from foreign countries. In any case, there is now a thriving and growing network of farmer’s markets, including one network of organic farmer’s markets in the autonomous community of Andalusia that comprises the cities of Granada, Sevilla, Córdoba, Almería, Cádiz, and Málaga [13,16,17,18].

Both the organic farmer’s market of Granada (called Ecomercado) and the RAG (Red Agroecológica de Granada), which is in charge of its management and organization, were born out of a Participatory Action Research (PAR) process in 2013 [15]. Initially, the regional administration invited groups linked to agroecology, both producers and consumers, as well as the other administrations and the PLANPAIS researchers from the University of Granada, which played a role as a facilitator team. The second author of this article participated in the PLANPAIS project, which addressed the complexity of pressures and opportunities that existed in the Vega of Granada (peri-urban area) [15]. The initial objective of this participatory process was to design an order to grant subsidies to short food supply chains in Granada as an alternative to the cancellation of subsidies for tobacco crops, which would mean an important change for the agriculture of the Vega of Granada, which had been dedicated to these subsidized crops for a century. It should be noted here that in the end, the subsidy order that was being designed in a participatory manner was not announced. However, from this moment on, the participatory process between agroecological organizations (production and consumption associations, producers’ organizations, small farmers, eco-shops, artisans) began, and they collectively decided to set up an open-air market for organic products, thus founding the Ecomercado de Granada, which held its first edition in May 2013. Subsequently, the RAG was founded as the organizing entity of the Ecomercado [16].

The Ecomercado is located on a walkway near Palacio de Congresos, a central area of the Granada capital city (population of 243,059 in 2021) [19] (Figure 1). Moreover, since 2013, this farmer’s market has been held on the first Saturday of every month including an average of 20 selling tents set up. After 2017, the farmer’s market is also celebrated every third Saturday of the month in the north area of the city (near the bus station) but with only 10 selling tents. The Ecomercado offers a pathway for local consumption of organic food and other complementary products ranging from books and clothes to fair trade products. It also offers a space for civil society organizations such as neighborhood associations, territorial defense entities, organizations that fight against climate change, etc.

Figure 1.

Granada farmer’s market. Source: created by the authors.

According to the RAG, the first goal of the Ecomercado is to inform the public about organic production, while caring for the natural environment, soil, and the Planet. The second goal is making the consumption of food more environmentally friendly. And the third goal is to provide a space for meeting and networking to connect the different areas of Granada and promote collaboration among the various social and economic sectors within them as well as the promotion of entrepreneurship and self-employment.

In order to achieve these goals, the organizational system of the Ecomercado is a key issue. In this sense, producer organizations are the preferred participants, favoring the collective nature of the Ecomercado, although the presence of some individual producers is also allowed. Operationally, it is organized as an assembly, with monthly meetings, where decisions involving all aspects of the Ecomercado are taken. There are also working committees that constitute the basic structure of the Ecomercado: Monitoring and Admissions Committee, Broadcasting–Promotion Committee, Activities Committee, Infrastructure and Maintenance Committee, and Economic and Management Committee with the City Council.

The type of products offered at the Ecomercado is a fundamental aspect. Organizations and farmers must sell their products in the Ecomercado and can only supplement them with 10% from other organizations or producers (Figure 2). As far as the origin of the products is concerned, they must come whenever possible from the province of Granada, where there were 189,863 ha of organic production in 2022 according to the Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación [20]. If they are not available in the province, they should come from Andalusia, where there were 1,345,805 ha of organic production according to the same source, and finally, if they are not available, they should come mainly from the Spanish state, where there are 2,843,612 ha cultivated in an organically certified manner. Likewise, the products must come from small organizations or organic producers, multinational companies are not accepted. With these limitations, the risk of them becoming intermediary markets, blurring out and losing the focus of the primary objectives, is avoided [21]. All Ecomercado products must be organically certified. These certifications are mostly carried out by companies that producers contract for this purpose. Some producers and their organizations also use participatory guarantee systems.

Figure 2.

Market flyer. Source: created by the authors.

On the other hand, the Ecomercado has no direct relationship with other short food supply chains, but indirectly it serves as a bridge for the participating producers to make the most of the encounter to bring products to other participants who use them in their short food supply chain strategies. The RAG, organizer of the Ecomercado, disseminates the short food supply chains between the general public so that consumers have the option of purchasing organic products between different markets. This action was particularly important during the COVID pandemic period. Markets in the city were banned for six months. The Ecomercado website published the different local organic shops where organic food could be purchased, reaching more than 100,000 visits in 2020.

Moreover, as mentioned above, the Ecomercado has not only focused on creating a space to sell. It has worked to make this space a meeting point (rural and urban worlds, social organizations, environmentalists, alternatives, producers, and consumers, etc.). Numerous activities have also been developed (talks, workshops, exhibitions, etc.) that have been the central axis of awareness-raising and information [16].

Among other characteristics, it is important to point out that the Ecomercado project is collective and totally self-financed, as it was born bottom-up, without any kind of public funding, with little support from the City Council, which limits itself to giving permission to occupy the public road on the day of the Ecomercado in exchange for payment of the corresponding fee by the RAG.

Finally, Granada has been a pioneer in the development of farmers’ markets in Andalusia, as it was one of the first, along with the organic farmers’ market in Sevilla and Guadalhorce, and has helped to energize other farmers’ markets in different Andalusian provinces.

Considering all the benefits that short supply chains in general, and farmers’ markets in particular, bring to the local community and the environment, it is a scientific necessity to study these short food supply chains and obtain information to promote them. However, despite finding numerous studies in the United States and Europe [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], there is a literature gap in the region of Andalusia, in southern Spain, especially in long-term studies. In addition, this is the first study that focuses on the Ecomercado of Granada.

The main objective of this study is to analyze the opinion of consumers of this farmers’ market. In this sense, this case study analyzes the main products purchased by consumers, the reasons for going to this market, the degree of satisfaction with market aspects, and opinions on possible changes.

This information can be valuable in helping the farmers’ markets in Granada and other markets in the autonomous community of Andalusia (most of which have recently developed) to be more successful. Additionally, this case study can serve as a basis to be replicated in other farmers’ markets, adapting it to their particular contexts, allowing them to make improvements based on consumer opinion.

Finally, another contribution of the focus of this research is that designs were carried out in a participatory way with members of the Ecomercado, which adds greater value to this research because it tries to study aspects that they consider important for the development of this initiative.

2. Materials and Methods

This study focused on the farmer’s market in Granada, Spain, and consisted of five surveys developed in 8 years, which are analyzed to help better understand the opinion of consumers of this market that was established in Spring 2013. The questionnaire has been the data collection technique applied in this study because it allows for obtaining and elaborating on a wide range of information quickly and efficiently, as well as its subsequent data analysis, being usually used in studies related to eating habits [30]. The questionnaire can be defined as a document that brings together the indicators of the variables included in the objective of the survey in a structured manner [31]. Specifically, in this case, a face-to-face questionnaire using a semi-structured format was designed for the first survey, with different types of questions (open questions, closed questions, and multiple-choice questions). The objective was to obtain and compile the largest amount of data and information possible, making the questionnaire as easy to use and as straightforward as possible for those who would answer it.

The data analysis technique used in this research is known as descriptive statistical analysis. A basic objective of this type of analysis is to determine the most relevant characteristics and profiles of individuals, groups, communities, or any other phenomenon that represents the object of the research [32].

The questions for the first survey in 2014 were created after a broad literature review. The references were shown to give strong insights into the consumer interests and would prove useful when helping farmers’ markets to be more successful.

In addition to this, the research group was involved in the creation of the Ecomercado and the first year of management, so 18 meetings about the farmer’s market, short food supply chains, and local farmer issues were attended, as well as field trips to the farms on behalf of the leading members of the Ecomercado. All this helped with the construction of the questionnaires.

The final version was discussed with the RAG. This is the ensemble of farmers’ associations that has been managing the Ecomercado since its foundation.

The first survey and the other 3 were passed out face to face at the Ecomercado, approaching the consumers directly. The first survey was on 5 April 2014 (62 responses), and it is considered a first approach to the initial state of the Ecomercado. The second survey was passed out in 2016 (November 5th and December 3rd, with 79 responses), and the third one in 2017 (on May 6th with 50 responses). Both consist of an evaluation of the first years of the Ecomercado once it was established in the city of Granada. The fourth one was carried out in June 2020 (145 responses online due to COVID restrictions), and the last one on 3 December 2022 (122 responses) (Table 1). These last surveys both constitute an updated vision of the Ecomercado in a difficult context and different to the one that could have been encountered at the beginning when the Ecomercado was founded [18]. During the face-to-face surveys, participants filled out questionnaires on their own, with the help of the research team.

Table 1.

Ecomercado Surveys.

A simple random sampling was used in this study, so the sample subjects were randomly selected. The criterion used was that the subject was a consumer of the Ecomercado, since our intention, as stated in the study, is to analyze the opinion of these consumers. Intentionally, the greatest possible balance/representativeness was sought in the selection of the last sampling unit (survey person) by considering sex/gender, age, and place of origin. These samples are not proportional to the number of consumers at the Ecomercado: this is an unknown fact, because with it being an open space, it is not possible to count rigorously how many people attend each edition of the Ecomercado, a number that also depends, among other things, on the weather or the season of the year. However, we consider that the sample allows us to obtain valuable knowledge in relation to our objectives, especially taking into account that this is a long-term study that has not been carried out in any other farmer’s market in Spain.

All the questionnaires followed the same structure so the questions for the customers collected information on four main categories: demographics, items bought, motives for attending the Ecomercado, and opinion on possible changes. Moreover, most questions were written to be answered by checking options for the sake of time with options to add comments.

In the first category, demographics was considered in order to gain knowledge about the socioeconomic profile of the customers. This section includes gender, age, number of people living in the household, marital status, and education. In addition, this information can highlight the type of people who are attracted to this type of food network, thus leading to possible improvements to attract a more diverse population as well as maintain the current customers. In this section, we also asked the consumers about the distance between the Ecomercado and their area of residence, as well as their means of transport.

The second category related to items bought provides information about products bought by the customers of the Ecomercado, allowing us to recognize what items have more demand and should be supplied and considered to improve its success. Moreover, customers also have an option to add what items they would like to see in the future. By doing so, communication is facilitated to offer direct opinions and give insights into possible new products to be introduced in the Ecomercado.

The third category, related to information on the customers’ motives for attending the Ecomercado, was measured by ranking options. The motives allow the Ecomercado organization to care about those reasons and increase the effort to consolidate these characteristics. In addition to this, it offers information on possible key questions to increase the popularity of farmers’ markets among the people of Granada.

The fourth category, opinions on possible changes, was considered to see what disparities currently exist in the Ecomercado. Customers were asked to rank how much they agreed with the problematic of the Ecomercado; it was written in this manner in order to facilitate reflection on possible issues that can be addressed in the following open question that was at the end of the survey. In addition, customers were asked about their attendance at other farmers’ markets and supply chains in order to gain more knowledge of their activity on Saturdays on which the Ecomercado is not there. The questionnaire also asked how often they would like to see the Ecomercado every month in order to consider possible new editions on other days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Questions asked in the surveys.

It should also be noted that all the questionnaire waves used very similar questions, and only the 2017 survey, for operational reasons at the time, was shorter. Thus, that year we only considered the following questions: gender, age, distance from the place of residence, reasons for going to the Ecomercado, places where they buy agroecological products when there is no Ecomercado, degree of satisfaction with the Ecomercado, and aspects to improve. Although this is a less complete survey than the other 4, we have decided to use the data for the analysis as they provide information to analyze the evolution of the consumers’ opinions of the Ecomercado.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The collected demographic results show that there is a general trend towards a certain type of customer. In the case of gender, there is a predominance of women in all the surveys ranging from 70 to 60% women, except on the first survey (2014), where men account for 53.8%. The main age range lay in between 30 and 60 years, ranging from 63% in 2022 to 79% in 2014. Young and older people are more present in the last surveys than in the first one, with the exception of the online survey where young people increase (30.3%), it is probably because of the bias of the online method means that there are more responses from people who are accustomed to using these media.

According to their living conditions, the vast majority of the consumers are married or live in couple, ranging from 70 to 60% in all the surveys apart from the online survey, where these consumers account for 52% due to previously mentioned bias in relation to the overrepresentation of young consumers in this survey. In addition to this, there is also a majority of consumers living in households of 1 or 2 people ranging from 75.6% in 2016 to 59.2 in 2022, and again 2020 appears with 41.8% of people in such households with a bias because it is an online survey answered by more young people than those representing the Ecomercado consumers.

In relation to the level of education, the vast majority of Ecomercado’s consumers have higher education, ranging from 74% in 2014 to 88% in 2022, with the remaining consumers having a high school diploma.

The majority of participants resided in Granada and its metropolitan area, and most of them between 0 and 3 km from the Ecomercado, ranging from 62.9% in 2014 to 72.8% in 2022. This way, most of the consumers travel by foot to the Ecomercado, ranging from 45% in 2014 to 68% in 2022. The second biggest group come to the Ecomercado by car, ranging from 32.3% in 2014 to 20.5% in 2016.

When asked about how they heard about the Ecomercado, most of the consumers mentioned from friends or family, ranging from 37.2% in 2014 to 62.3% in 2022. The Internet was always the second choice (20–25%).

3.2. Items Bought

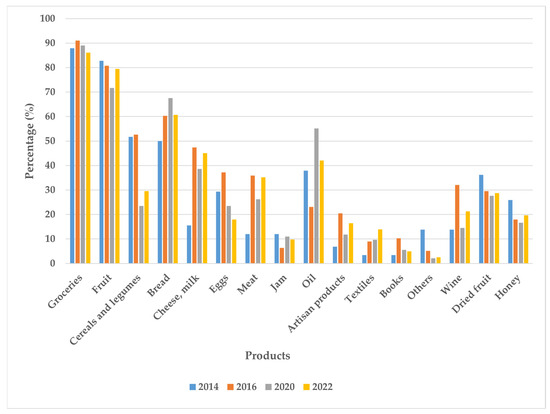

In relation to which products consumers usually buy at the market, the most popular types of products became clear: fruit and vegetables are the most consumed products in the Ecomercado. According to Figure 3, positive responses are always above 80% in both products, arriving at 90% in the case of vegetables. Other popular products presented in order are: cereal and legumes, bread, cheese, and olive oil.

Figure 3.

Products bought in 2014, 2016, 2020, and 2022. Source: created by the authors.

In terms of the evolution of the products purchased, there are some noteworthy aspects. Firstly, it stands out that most of the products purchased by consumers had a significant decrease in 2020. This is probably due to the restrictions that existed to attend the Ecomarket during this year due to COVID-19. The products that declined the most were cereals and legumes, wine, and eggs, which decreased between 2016 and 2020 by 29.1%, 17.6%, and 13.7%, respectively. The products that decreased more moderately were honey (1.3%), dried fruit (1.9%), and groceries (2%). Bread, ham, oil, and textiles increased their purchases. The purchase of oil is notorious with an increase of 32.1%.

Regarding the difference in the purchase of products between 2014 and 2022, there was a decrease in half of the products and an increase in the purchase of the other half. Regarding the products that were purchased less, cereals and legumes stand out with a decrease of 22.2%. In second place are eggs, which fell by 11.3%. As for the products that increased their purchase, the most notable is dairy products (cheese and milk) with an increase of 29.6%, followed by meat, which increased its purchase by 23.2%. The only product that showed a linear progression was textiles, which, although moderately, increased its purchase by consumers in all years.

3.3. Motivations

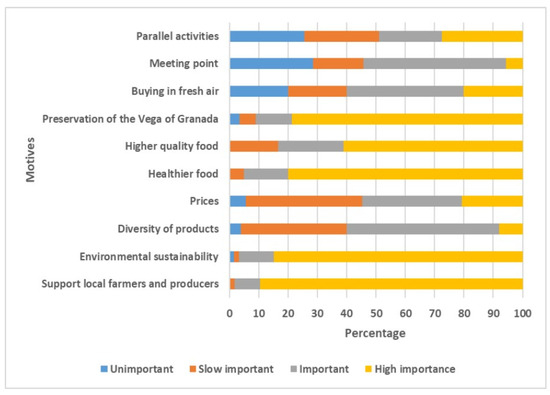

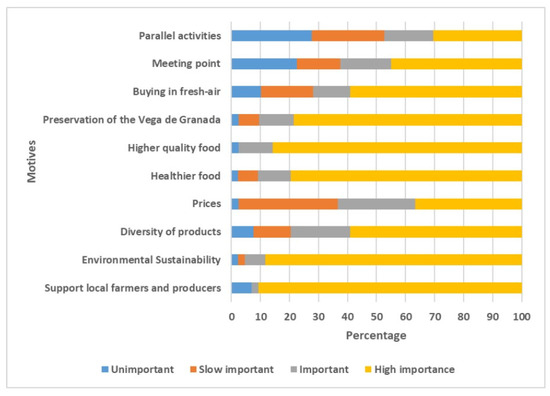

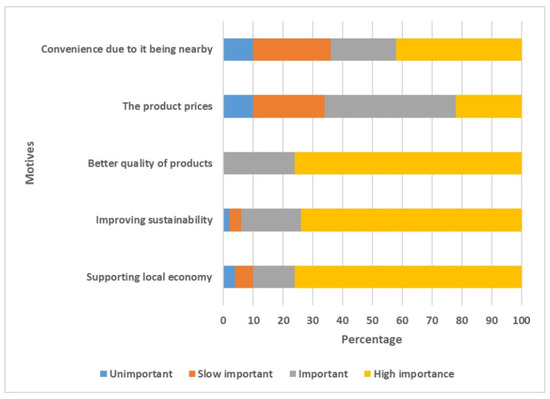

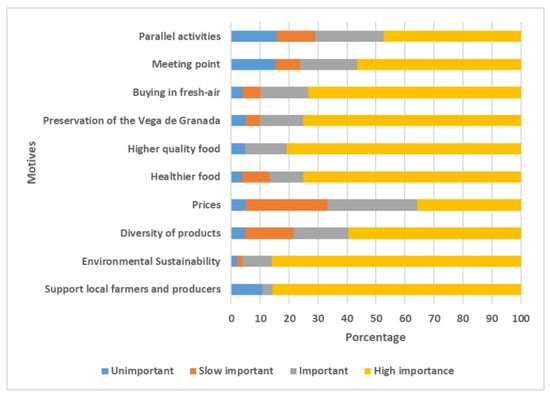

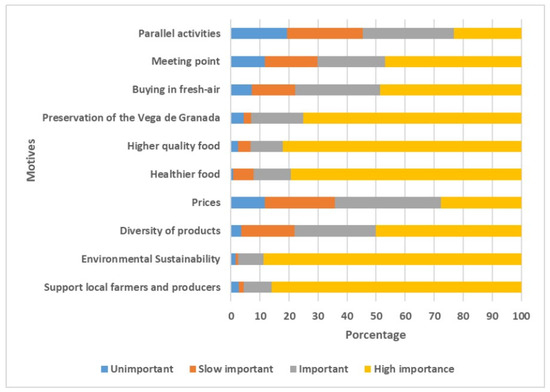

Customers were also asked about their motives for attending the Ecomercado. As shown in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, in all the surveys, customers stated that their number one motive was to support the local economy, with the consideration of very important for the consumer decision ranging from 85 to 90%, except in the case of 2017, when this motive was the first one but only for 76%. The next main motive was to contribute to environmental sustainability with a similar percentage compared to the first case. Finally, to obtain higher quality and more healthy food was the third main motive, with a slightly lower percentage of consumers affirming that this was very important for them when buying at the farmer’s market (from 61% in 2014 to 85% in 2016).

Figure 4.

Motives for attending the Ecomercado in 2014. Source: created by the authors.

Figure 5.

Motives for attending the Ecomercado in 2016. Source: created by the authors.

Figure 6.

Motives for attending the Ecomercado in 2017. Source: created by the authors.

Figure 7.

Motives for attending the Ecomercado in 2020. Source: created by the authors.

Figure 8.

Motives for attending the Ecomercado in 2022. Source: created by the authors.

Analyzing the evolution of motivations, the data show that, between 2014 and 2022, the unimportant reasons that increased their percentage were price (6.48%), buying in fresh air (3%), and parallel activities (3.65%), which means that these motivations have become less important for consumers in this wave of surveys. On the other hand, among the motivations considered to be of high importance, healthier food (4.31%), environmental sustainability (2.79%), higher quality (1.1%), and support local farmers and producers (0.39%) have increased. The rest of the motivations considered to be of high importance have decreased, except for preservation of the Vega of Granada, which has remained the same. Although, as can be seen, the variations have been insignificant.

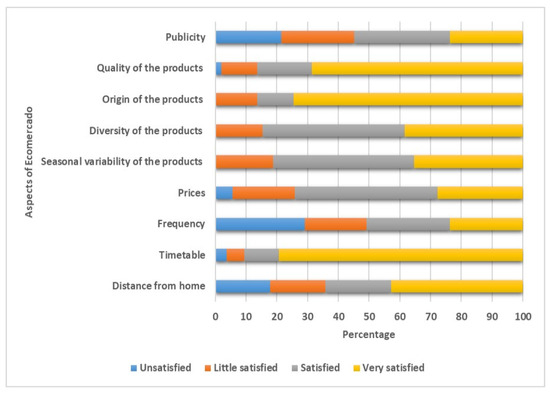

3.4. Opinion on Possible Changes

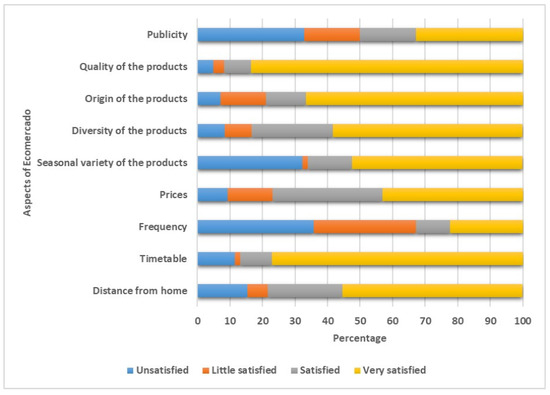

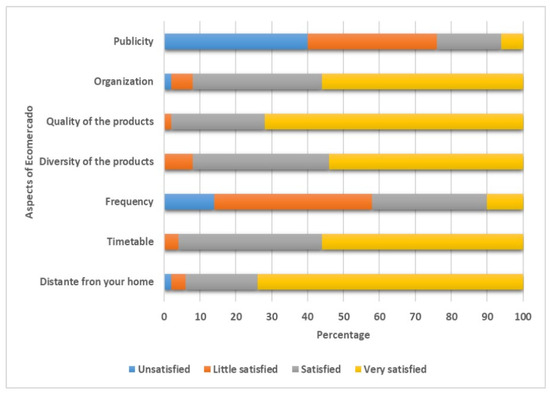

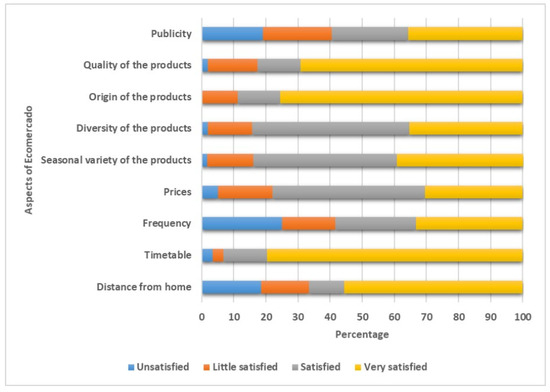

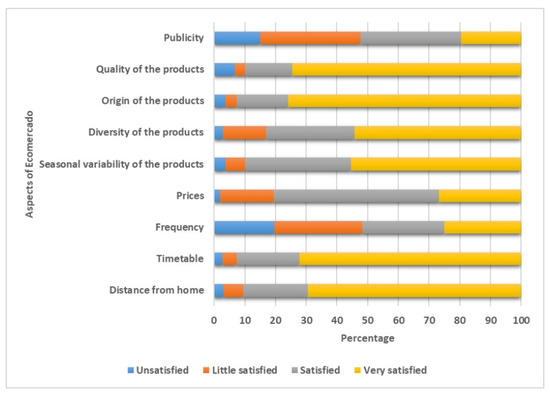

Consumers were also asked to rank their satisfaction with some aspects of the market. In this case, the most blatant trend in the data illustrated that having the market only once a month is the biggest problem for consumers; this is always pointed out by consumers in the open question and has the largest percentage of unsatisfied or low satisfaction ranging from 42% in 2020 to 67% in 2016, as can be seen in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13. Other questions that are considered problematic by consumers in relation to the satisfaction with the farmer’s market are diversity and variability of products only in 2014 and 2016, and lack of publicity that is not satisfying for 35–45% of the respondents in all the surveys.

Figure 9.

Satisfaction with aspects of the Ecomercado in 2014. Source: created by the authors.

Figure 10.

Satisfaction with aspects of the Ecomercado in 2016. Source: created by the authors.

Figure 11.

Satisfaction with aspects of the Ecomercado in 2017. Source: created by the authors.

Figure 12.

Satisfaction with aspects of the Ecomercado in 2020. Source: created by the authors.

Figure 13.

Satisfaction with aspects of the Ecomercado in 2022. Source: created by the authors.

Regarding the evolution of consumer satisfaction with the aspects of the Ecomercado, firstly, it can be observed that during the year 2020 of the COVID-19 pandemic, the percentage of unsatisfied people decreased comparing to 2016 in all aspects except distance. It is possible that the degree of satisfaction with the distance decreased due to the impossibility of some people to get to the Ecomercado, especially those regular consumers who live in municipalities far from the city. The aspects in which the percentage of unsatisfied people decreased more were the seasonal variability of the products (30.41%), publicity (13.71%), and frequency (10.82%).

In comparative terms between 2014 and 2022, dissatisfaction has decreased in the following aspects: distance from home (14.7%), timetable (0.99%), frequency (9.45%), prices (3.71%), and publicity (6.48%). As can be seen, the aspect with the greatest decrease in dissatisfaction was frequency, possibly due to the opening of another Ecomercado in the northern part of the city. However, there are aspects in which dissatisfaction has increased slightly in this period of time, specifically the seasonal variability of the products (3.64%), the diversity of the products (2.8), the origin of the products (3.7%), and the quality of the products (4.82%).

Regarding the percentage of people who are very satisfied with the aspects of the Ecomercado, almost all aspects have improved between 2014 and 2022. Among them, the aspect that has improved the most is the timetable, with an increase of 26.1%. The only aspects in which the percentage of very satisfied consumers decreased were the frequency and seasonal variability of the products, with a decrease of 7.3% and 0.93%, respectively.

Finally, the surveys had an open question where consumers could indicate their opinions, comments regarding possible improvements to be made to the Ecomercado, and possible proposals. We therefore give a brief description of the highlights here. First of all, as we have pointed out above, in most cases consumers affirm that there should be more frequency with the Ecomercado, and they even suggest that other editions could be spread throughout different neighborhoods or locations in Granada and its metropolitan area.

On the other hand, consumers in certain cases demand a greater diversity of products, sometimes pointing to the demand for a greater presence of products such as meat or fish, and even some everyday handicrafts that are not currently present.

Similarly, they demand more information about the origin of the products from the farmers/producers and that the price of each product should be more visible at the time of purchase so they do not have to ask the staff in charge.

They also stress that it is important to improve and redefine advertising and consumer information dissemination mechanisms beyond the website and social media.

Consumers also pointed out the necessity to develop activities, such as thematic workshops aimed at children and adults, focused on a greater knowledge of ecology and agriculture (for example, one on “how to set up your own vegetable garden”) and fun activities aimed towards social education. Some people proposed workshops in which people could be taught and informed about the process of making products, as well as talks or colloquiums.

As additional services, consumers have also proposed the installation of leisure facilities such as small tents or bars, where consumers can enjoy refreshing drinks, wine, beer, or organic snack tasting in a relaxed way, as well as having stands where natural organic juices are made.

4. Discussion

The different surveys demonstrate patterns that characterize the Ecomercado more than trends or changes over time. The only exception is related to the growing percentage of consumers who were informed of the existence of the Ecomercado by previous consumers. This trend demonstrates that the Ecomercado is consolidated and that the positive opinions of consumers is one of its main strengths, as we will describe in the following paragraphs.

As for demographics in the Ecomercado, there seems to be some clear patterns. One of the most prevalent patterns observed is that farmers’ markets seem to be more frequented by women than by men, which is aligned with other farmers’ markets in similar countries, where several studies showed that the percentage of female consumers was significantly higher than the percentage of males [23,27,29,33,34,35,36,37,38], only in the case of India it was completely the opposite, probably because of cultural reasons [24].

The surveys developed in the Ecomercado also showed that people in the middle age range attend farmers’ markets more than young people according to the percentage ratio of census ages to ages of people attending. Again, this finding has been common among farmer’s market studies, illustrated in several sources [23,26,27,29,36,38].

Another important element is the level of education. The results in the case of the Ecomercado show a high level of education among all consumers, something we find in other similar studies on farmers’ markets [23,27] and in general about the consumption of organic products [17,39,40,41].

On the other hand, most of the consumers of the Ecomercado come from nearby places and come mainly on foot, so that not only the products but also those who consume them are local, as is the case in other places [36,42], despite the fact that Granada is a city with an important tourism sector [43] that tends to have a strong interest in this type of activity [44,45]. This results in sustainable mobility not only in distribution but also in commercialization, reducing the carbon footprint of both production and consumption.

In terms of products, the results obtained for the case of the Ecomercado show that more than 80% of consumers are looking for fresh fruit and vegetables that are mostly local. This element is directly related to the fact that consumers look for healthy and quality products in the Ecomercado, so that this question is important for the majority of consumers when choosing the Ecomercado as a place to buy, especially if we take into account that the farmer’s market in Granada has the peculiarity that it only allows the sale of organic products certified by a third party or through participatory certifications (Participatory Guarantee Systems) [46].

This issue of the importance of product quality and healthiness as a reason for shopping at farmer’s markets is consistent with most of the studies consulted. In fact, in two studies developed in a North Carolina farmer’s market [28,47], it was found that consumers come to the market mainly to buy fresh quality products and that price was not an important factor. Research conducted in 2011 [48] shows that the main motive of participation of customers in the Eastern Los Angeles farmers’ markets revolves around an increasing interest in healthy food. In Europe, Neuman and Mehlkop [25] demonstrate in a broad study that local, sustainable, and healthy products are the drivers for consumers to buy in the farmers’ markets of Germany. Vecchio [22] found that incentives for alternative food markets were largely driven by regional quality production and direct selling in Italy, Spain, France, Greece, and Portugal; on quality definitions such as sustainability or animal welfare, and on innovative forms of marketing in countries such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Germany. A broad study developed in Romania by Polimeni et al. [23] also describes how the consumers buy at farmers’ markets because of their environmental and health concern, as well as the possibilities of community building. According to research conducted in the Czech Republic, fresh and healthy food are also the key reasons for consumers to buy at the farmers’ markets, and, in this case, price and inconvenient opening hours were the main complaints by the consumers [49]. In a study of five Scottish farmers’ markets, Lyon et al. [50] found that consumer buying at farmers’ markets was justified by the high quality of the food being sold, with price being seen as a good value for what they were buying. Another recent study in Scotland by Wardle et al. [42] shows that quality, nutrition, and organic status were key questions for consumers when choosing the farmers’ markets. Through 38 interviews given at farmers’ markets in the UK, Spiller [51] found that many consumers have the perception that food from farmers’ markets actually tastes better than food from supermarkets.

In other parts of the world such as Turkey [27] and Australia [52], the literature shows similar interest by consumers in relation to healthy, fresh, sustainable, and local products, and the researchers have described the importance of social aspects in farmers’ markets. In India, another study shows that consumers of the farmers’ markets are interested in fresh and organic products, and in the possibility of buying products directly from the farmers [24].

In any case, the main reason for consumers to buy in the Ecomercado is to support the local economy, including supporting local farmers. This makes an important difference with most of the research conducted in other parts of the world, but there are also some cases where local economy is a key factor. For example, in Italy, a country with lots of similarities with Spain, there are several research studies that show that the consumers choose farmers’ markets because they are contributing to increase farmers’ income [26,44,45]. A recent study in Parma (Italy) showed that farmers’ markets have an important economic impact in the local economies because farmers tend to buy their supplies in the local market, increasing the local economic flow [53]. In addition to this, the research conducted by Gayathri et al. [24] in India showed that farmers’ markets are good for the local economy, because they support self-employed farmers and keep money within the community instead of sending it across the world through the global food system and the global food corporations. Farmers’ markets have also increased in popularity because of the increasing economic advantages of buying locally. One study conducted in Portland, ME, USA [54], found that for every $100 spent locally, $58 stays within the local economy, while for every $100 spent at a chain store only $33 stays in the local economy. According to this study, if consumers shifted 10% of buying from chain stores to local businesses, it would result in $127 billion in additional economic activity and be able to create 874 new jobs in the community.

Another difference from the Ecomercado is that the second motive to buy there was the environmental benefits; this is including the conservation of agricultural landscapes, as land can be used economically by farming and offers an alternative to using it for urban development and expansion of renewable energy infrastructure, which is a key question in Granada [15,18,55,56,57]. It is again aligned with the Italian case where there are several studies that show that consumers choose farmers’ markets because of the environmental benefits [26,44,45].

In relation to the assessment of different aspects of the Ecomercado, a very important element is that consumers did not point to prices as being a problem, rather, most consider them to be adequate despite the fact that organic products are generally somewhat more expensive than conventional ones [58]. As noted above, this reality is similar to what has been studied in most of the research on farmers’ markets we have found, where precisely prices are an incentive to purchase, or at least not an impediment [28,47,50]; only, in the case of the Czech Republic, consumers complained about prices as a problem in the farmers’ market [49].

In this same context of evaluation of the Ecomercado, the consumers also responded in the survey that they are happy to buy local varieties, local products, and local gastronomy from local farmers. According to this, also in the case of Spain, another research study shows that apart from buying local and quality products, embeddedness between farmers and consumers was one of the main reasons to buy in the farmers’ markets [59]; identity is not only related to food and land but also to the farmers who are producing this food. In addition to this, recent research conducted by Lombardi et al. [45] in the whole of Italy and also in the case of Rome [44] shows that farmers’ markets are an important part of the local identity and thus a key tourism attraction in this Mediterranean country.

To conclude this discussion, it is noteworthy that both the Ecomercado of Granada and farmers’ markets in general offer a variety of advantages, both in an environmental and local context. Environmentally, local food systems, and thus farmers’ markets, provide food to people while reducing the copious amounts of energy and fossil fuels often wasted when importing and exporting products from across the world in the global food system [22,23,24,44]. This is the case in the farmers’ market analyzed since most of the products come from local agriculture in Granada. In addition to this, conventional commercial areas, and most often malls, are consuming much more energy in terms of consumer mobility (mainly private cars) and in terms of building requirements that are much lower in open-air or seasonal markets compared to other commercial areas. According to the previous, local food production and distribution for farmers’ markets entails a reduction in air pollution and natural environment pollution associated to food production and distribution [25,42]. This aspect is also expressed in the Ecomercado since, as mentioned in the results, most consumers come on foot.

Local food for farmers’ markets is often produced on a much smaller scale and in many cases is organic, as happens in our case study, meaning that natural regulation systems, such as crop rotation and diversification, can be used to ward off pests and maintain soil fertility instead of the use of pesticides and fertilizers that degrade the natural environment and introduce potentially dangerous chemicals into our food [22,23,25,26,27,44,45].

From a health standpoint, local food from the Ecomercado and farmers’ markets can be picked as it is needed more easily from the field or the farm, meaning that products are fresh and preservatives are less necessary, which eliminates many potentially dangerous chemicals from our food [22,24,25,27,28,47,48,49,52].

As noted above, farmers’ markets have also increased in popularity because of their increasing economic advantages. Buying locally has been shown to improve the profits of local farmers, create local jobs, result in more local buying, and increase money for local taxes and investments in the community [21,24,38,44,45,53,54,59,60].

Farmers’ markets offer an opportunity for the conservation of natural land, as land can be used economically by sustainable farming and offers an alternative to using it for urban development [44,45,48] and expansion renewable energy infrastructure in the countryside [61]. Some local farms also offer community education activities and help consumers connect with the land and the food that they eat [52]. This aspect is particularly important in Granada, where 40% of the fertile agricultural area of its peri-urban space has been lost in the last fifty years, accompanied by a decrease in the number of farmers [57].

Moreover, as happens in the Ecomercado, farmers’ markets act as a link between farmers and the community, increasing education opportunities [59].

Finally, within many other advantages, farmers’ markets are also an important cultural and identity asset of a city or a territory, as local varieties, local products, and local gastronomy can be easily found in farmers’ markets [44,45,59].

5. Conclusions

The Ecomercado is a consolidated activity that has lasted for more than ten years because of the positive opinions of the consumers and their role as the main marketing channel to attract new consumers. This high valuation of the Ecomercado is related both to the explicit answers in the survey and to the consumers’ demand to increase the frequency from once a month to fortnightly or weekly, and even to the proposal to hold the Ecomercados in other parts of the city. For this, potential locations should be studied as well as the availability of producers and the opinion of consumers.

According to this, the research on the Ecomercado has highlighted the importance of building new networks and short food supply chains as powerful alternatives to conventional food systems. The Ecomercado project has established itself not only as a sales point for local and organic products but also as a social meeting place, advocating sustainability and support for the local economy, as well as recognition of the work carried out by farmers and the high quality of their products. Relationships and direct links are established between producers and consumers, who recognize and value the work and dedication to the project.

This study shows that it is a key to improve and redefine advertising mechanisms. These must be focused and thought out with respect to the possibilities presented by each population group, both the younger and older sectors. In this way, it will be possible to reach a larger and more diverse percentage of the population.

It is important to be able to develop some kind of combined project or strategy with public entities, so that they realize the importance of short food supply chains on an economic, social, and cultural level, and therefore, their participation and support is not practically nil as it is at present. All of this is imperative in order to remove the economic barriers that limit the expansion and growth of the Ecomercado, as it is a totally self-financed project.

In this sense, this study may have implications for the Ecomercado in other farmers’ markets in order to formulate measures to improve them. In particular, as shown in this study and in the literature consulted on farmers’ markets, the majority of consumers are women, highly educated and middle-aged. In this sense, for farmers’ markets to become established, it is necessary for strategies to reach more layers of the population, especially economically disadvantaged consumers. This can be alleviated with public policies that, recognizing the socioeconomic and environmental advantages of farmers’ markets, support these initiatives. In addition, public actions and policies related to food education could contribute to ensuring that food is not restricted to chefs or women but managed by the entire population.

Another important point would be to address the proposals that have been pointed out by consumers in the open questions of the different waves of surveys. Carrying out a greater number of recreational activities and informative workshops on ecology and products derived from agroecological practices would be good ideas aimed at achieving greater involvement and participation on the part of the population, as well as holding talks and tasting sessions. It should also be borne in mind that all of this involves an economic investment and should therefore be studied in depth, taking into account the resources available.

In this context, it should not be forgotten that the project advocates the construction of an alternative agro-food system presenting important economic and social benefits, helping local growth, and participating in the creation of self-employment and the maintenance of a healthy way of life, objectives that are of great interest to the population, above all to its most conscious part, and which should therefore also be of interest to public institutions.

Finally, we would like to point out that the Ecomercado project has an enormous potential that has not yet been fully developed or shown. In this context, important challenges such as those indicated above still need to be faced, for which new strategies or plans need to be developed to foster interest on the part of the population, broadening their horizons and expanding the organic local market, in order to build the pillars for the development of an alternative and sustainable agri-food system based on local and seasonal production.

6. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Firstly, this study used simple random sampling, so the sample subjects were selected randomly, with the only selection criterion being that the subject was a consumer of the Ecomercado, since our intention, as shown earlier in the study, is to analyze the opinion of these consumers. In future lines of research, it would be interesting to carry out a stratified sampling to check how variables such as age, sex, or socioeconomic level affect the survey. Similarly, we believe that future research could include in the sample people who do not consume products at this farmers’ market, which could be useful for promoting strategies to reach these consumers.

The information obtained in this study allows for describing, analyzing, and improving the Ecomercado of Granada and can illustrate similar experiences. However, future studies could analyze other farmers’ markets in Andalusia and other regions, which would allow comparisons to be made.

Finally, future studies could conduct a comprehensive analysis of the sustainability of the farmers’ markets under consideration, to assess its impact on the local community. In particular, quantitative studies could analyze aspects such as the impact on the efficient use of resources, combined with qualitative analyses to study aspects such as the impact on the working conditions of its members, the relationship between farmers and the community, or the improvement of nutritional health of consumers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.P.R., A.M.R., A.J.T.R., C.E.d.l.C.A., J.S.C., A.R.D., S.V.B., and J.C.M.M.; formal analysis, F.J.P.R. and A.M.R.; investigation, F.J.P.R., A.M.R., A.J.T.R., C.E.d.l.C.A., J.S.C., A.R.D., S.V.B., and J.C.M.M.; methodology, F.J.P.R., A.M.R., and A.J.T.R.; supervision, F.J.P.R., A.M.R., and J.S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.P.R. and A.M.R.; writing—review and editing, F.J.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research: which is part of a PhD thesis written by Francisco Javier Peña Rodríguez, has been carried out at the University of Granada (Spain) with a 4-year predoctoral contract for the training of University Teaching Staff (Contrato predoctoral para la Formación del Profesorado Universitario (FPU)). This research is also part of the Healthy Municipal Soils project funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the grant agreement No101091050.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The predoctoral contract mentioned in the previous paragraph was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Universities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ETC Group. Who Will Control the Green Economy? ETC Group: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2011; Available online: https://cutt.ly/9wVsH9dJ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Peña Rodríguez, F.J.; Yacamán, C.; Matarán Ruiz, A. Agri-Food Supply Chains in Southern and Eastern Europe. In Frontiers in Agri-Food Supply Chains: Frameworks and Case Studies; de Leeuw, S., van der Vorst, J., Eds.; BDS Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fadón, B.; López García, D. Cómo Vender Directamente Nuestras Producciones Ecológicas. Canales Alternativos Para La Comercialización De Los Alimentos Ecológicos En Mercados Locales; CEDER Cáparra: Cáceres, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gallar, D.; Saracho Domínguez, H. Consumo de Productos Ecológicos En Andalucía. Un Abordaje Integral; Congreso Español de Sociología: Gijón, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, C.; Gómez, S.; Wilkinson, J. Acaparamiento de Tierras y Acumulación Capitalista: Aspectos Clave En América Latina. Rev. Interdiscip. Estud. Agrar. 2013, 38, 75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Yacamán Ochoa, C.; Matarán, A.; Mata Olmo, R.; López, J.; Fuentes-Guerra, R. The Potential Role of Short Food Supply Chains in Strengthening Periurban Agriculture in Spain: The Cases of Madrid and Barcelona. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, E. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Simón Fernández, X.; Copena, D.; Pérez Neira, D.; Delgado Cabeza, M.; Soler Montiel, M. Alimentos Kilométricos y Gases de Efecto Invernadero: Análisis Del Transporte de Las Importaciones de Alimentos En El Estado Español (1995–2007). Revibec Rev. La Red Iberoam. Econ. Ecológica 2011, 22, 0001–0016. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Neira, D.; Copena Rodríguez, D.; Delgado Cabeza, M.; Soler Montiel, M.; Simón Fernández, X. ¿Cuántos Kilómetros Recorren Los Alimentos Antes de Llegar a Tu Plato? Análisis de La Presión Ambiental Del Transporte de La Importación de Alimentos (Consumo Humano, Industria o Consumo Animal) En El Periodo 1995–2011; Amigos de la Tierra, 2011. Available online: https://cutt.ly/4wVsNnQR (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- EIP-AGRI. EIP Focus Group Innovative Short Final Report Food Supply Chain Management; EIP-AGRI: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://cutt.ly/8wVs2s8x (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Aubry, C.; Kebir, L. Shortening Food Supply Chains: A Means for Maintaining Agriculture Close to Urban Areas? The Case of the French Metropolitan Area of Paris. Food Policy 2013, 41, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfani, D.; Matarán Ruiz, A. Bioregional Planning and Design: Volume II; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-46082-2. [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz, C.; Haro, I.; Molero, J. Los Mercados Hoy: Una Aproximación Desde La Agroecología. Fertil. La Tierra Rev. Agric. Ecológica 2016, 66, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. What Is a Farmers’ Market? USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://cutt.ly/8w6XgxQ2 (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Matarán Ruiz, A.; Yacamán Ochoa, C. Participative Agri-Food Projects in the Urban Bioregion of the Vega of Granada, Spain. In Bioregional Planning and Design: Issues and Practices for a Bioregional Regeneration; Fanfani, D., Matarán Ruiz, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz A, C.; Matarán Ruiz, A.; Hung, J.; Knudson, E. Relaciones Entre Productores y Consumidores. Confianza Integral En La Agroecología a Través de Los Canales Cortos de Comercialización. LEISA Rev. Agroecol. 2017, 33, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Almazán Castro, L.; Herrera-Gil, M.; Escobar-Cruz, M. Sistemas Alimentarios Territorializados En España. In 100 Iniciativas Locales Para Una Alimentación Responsable y Sostenible; Cerai-Carasso: Valencia, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matarán Ruiz, A.; López Medina, J.M.; de la Cruz, C.; Fuentes-Guerra Soldevilla, R.; Soler Montiel, M.; de Hond, I.; Mozo Peñalver, G.; Arcos, J.M.; Sánchez Contreras, J. Participative Assessment of Agroecological Networks and Proposals for Improvement: Case Study of Andalusia (Spain). Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 48, 660–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Estadística Continua de Población. Últimos Datos; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://cutt.ly/VwVdrKrw (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Producción Ecológica. Estadísticas 2022; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Catálogo de Publicaciones de la Administración General del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://cutt.ly/rwVduM7d (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Mauleon, J.R. Mercados de Agricultores En España: Diagnóstico y Propuesta de Actuación. Ager: Rev. De Estud. Sobre Población Y Desarro. Rural 2012, 13, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R. European and United States Farmers’ Markets: Similarities, Differences and Potential Developments; University of Naples “Parthenope”: Naples, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Polimeni, J.M.; Iorgulescu, R.I.; Mihnea, A. Understanding Consumer Motivations for Buying Sustainable Agricultural Products at Romanian Farmers Markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, S.; Vikraman, A.; Vinuchakravarthi, V.; Srinivasan, S. Farmers’ Market: Consumer Trends, Taste, Preferences, and Characteristics towards Buying Value Added Products Directly from Producer. J. Postharvest Technol. 2023, 11, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, R.; Mehlkop, G. Revisiting Farmers Markets—Disentangling Preferences and Conditions of Food Purchases on Countrywide Data from Germany. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 106, 104815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietri, E.; Koemle, D.; Yu, X.; Finco, A. Consumers’ Sense of Farmers’ Markets: Tasting Sustainability or Just Purchasing Food? Sustainability 2016, 8, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adanacioglu, H. Factors Affecting the Purchase Behaviour of Farmers’ Markets Consumers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreatta, S.; Wickliffe, W. Managing Farmer and Consumer Expectations: A Study of a North Carolina Farmers Market. Hum. Organ. 2002, 61, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, R.; Zurbriggen, M.; Italia, J.; Adelaja, A.; Nitzsche, P.; VanVranken, R. Farmers’ Markets: Consumer Trends, Preferences, and Characteristics; New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Anguita, J.C.; Labrador, J.R.; Campos, J.D. La Encuesta Como Técnica de Investigación. Elaboración de Cuestionarios y Tratamiento Estadístico de Los Datos (I). Aten Primaria 2003, 31, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, A.J.; Fernández, J.S.; Pérez, C. Investigar Mediante Encuestas Fundamentos Teóricos y Aspectos Prácticos. Psicothema 2000, 12, 320–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, P. Fundamentos de Metodología de La Investigación; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Onianwa, O.; Mojica, M.; Wheelock, G. Consumer Characteristics and Views Regarding Farmers Markets: An Examination of On-Site Survey Data of Alabama Consumers. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2006, 37, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry Wolf, M.; Spittler, A.; Ahern, J. A Profile of Farmers’ Market Consumers and the Perceived Advantages of Produce Sold at Farmers’ Markets. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2005, 36, 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jekanowski, M.D.; Williams, D.R.; Schiek, W.A. Consumers’ Willingness to Purchase Locally Produced Agricultural Products: An Analysis of an Indiana Survey. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2000, 29, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. Farmers’ Market Research 1940–2000: An Inventory and Review. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 2002, 17, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrington, K.; Dennis, J.H.; Mazzocco, M. An Evaluation of Consumer Segments for Farmers’ Market Consumers in Indiana and Illinois; Research in Agricultural & Applied Economics: Santa Clara, CA, 2010; Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/93919/ (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Abelló, F.J.; Palma, M.A.; Waller, M.L.; Anderson, D.P. Evaluating the Factors Influencing the Number of Visits to Farmers’ Markets. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2014, 20, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehurst, G.; Afonso, C.; Martins Gonçalves, H. Re-examining Green Purchase Behaviour and the Green Consumer Profile: New Evidences. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-González, P.; López Miguens, M.J.; González-Vázquez, E. El Perfil Del Consumidor Ecológico En España. ESIC Mark. 2015, 46, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez González, I. Hábitos De Consumo De Los Productos Ecológicos En La Provincia De Lugo (España). Braz. J. Agroecol. Sustain. 2021, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Sorathia, A.; Smith, P.; Feliciano, D. Environmental, Social and Economic Perceptions of Local Food Production: A Case Study of Aberdeenshire Farmers’ Markets. Scott. Geogr. J. 2023, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Valverde, F.A.; Capote Lama, A. ¿Overtourism En La Ciudad de Granada?: Una Aproximación a La Percepción de Turistas, Residentes y Partidos Políticos Locales. Cuad. Geográficos 2020, 60, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, G. Check for Urban Food Markets and Community Development. In Foodscapes: Theory, History, and Current European Examples; Manetti, C., Staniscia, B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, G.; Manetti, C.; Staniscia, B. Urban Food Markets and Community Development. In Foodscapes. Theory, History, and Current European Examples; Kühne, O., Fischer, D.O., Sedelmeier, T., Hochschild, V., Staniscia, B., Manetti, C., Dumitrache, L., Talos, M.A., Menéndez Rexarch, A., de Marcos Fernández, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- IFOAM. Sistemas Participativos de Garantía—Estudios de caso de América Latina; IFOAM: Bonn, Germany, 2013; Available online: www.ifoam.org (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Carson, R.A.; Hamel, Z.; Giarrocco, K.; Baylor, R.; Mathews, L.G. Buying in: The Influence of Interactions at Farmers’ Markets. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelas, V.; Iverson, E.; Kiekel, P.; Peters, A. The Role of Farmers’ Markets in Two Low Income, Urban Communities. J. Community Health 2012, 37, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorná, J.; Pilař, L.; Balcarová, T.; Sergeeva, I. Value Proposition Canvas: Identification of Pains, Gains and Customer Jobs at Farmers’ Markets. AGRIS Line Pap. Econ. Inform. 2015, 7, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, P.; Collie, V.; Kvarnbrink, E.; Colquhoun, A. Shopping at the Farmers’ Market: Consumers and Their Perspectives. J. Foodserv. 2009, 20, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, K. It Tastes Better Because … Consumer Understandings of UK Farmers’ Market Food. Appetite 2012, 59, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kane, G.; Wijaya, S.Y. Contribution of Farmers’ Markets to More Socially Sustainable Food Systems: A Pilot Study of a Farmers’ Market in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Australia. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2015, 39, 1124–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, R.; Arfini, F.; Baldi, L.; Donati, M. Economic Impact of Short Food Supply Chains: A Case Study in Parma (Italy). Sustainability 2023, 15, 11557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Martin, G. Ideas For Shared Prosperity; Maine Center for Economic Policy: Augusta, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Ruiz, J.; Matarán Ruiz, A. La Vega de Granada: The Defence of a Paradigmatic Agrarian Heritage Space by Local Citizens. In Urban Agriculture and the Heritage Potential of Agrarian Landscape; Scazzosi, L., Branduini, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Cejudo García, E. Actividades productivas agrarias de y para la Vega de Granada. In Por un Desarrollo Sostenible de la Vega de Granada (España); Maroto Martos, J.C., Pinos, A., Eds.; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2021; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Rodríguez, F.-J.; Entrena-Durán, F.; Ivorra-Cano, A.; Llorca-Linde, A. Changes in Land Use and Food Security: The Case of the De La Vega Agrarian Shire in the Southern Spanish Province of Granada. Land 2023, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, T.C.; Mizik, T. Comparative Economics of Conventional, Organic, and Alternative Agricultural Production Systems. Economies 2021, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oñederra-Aramendi, A.; Begiristain-Zubillaga, M.; Malagón-Zaldua, E. Who Is Feeding Embeddedness in Farmers’ Markets? A Cluster Study of Farmers’ Markets in Gipuzkoa. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, C.C.; Gillespie, G.W.; Feenstra, G.W. Social Learning and Innovation at Retail Farmers’ Markets. Rural Sociol. 2004, 69, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Contreras, J.; Matarán Ruiz, A.; Campos-Celador, A.; Fjellheim, E.M. Energy Colonialism: A Category to Analyse the Corporate Energy Transition in the Global South and North. Land 2023, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).