Transformational and Transactional Leaders and Their Role in Implementing the Kotter Change Management Model Ensuring Sustainable Change: An Empirical Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

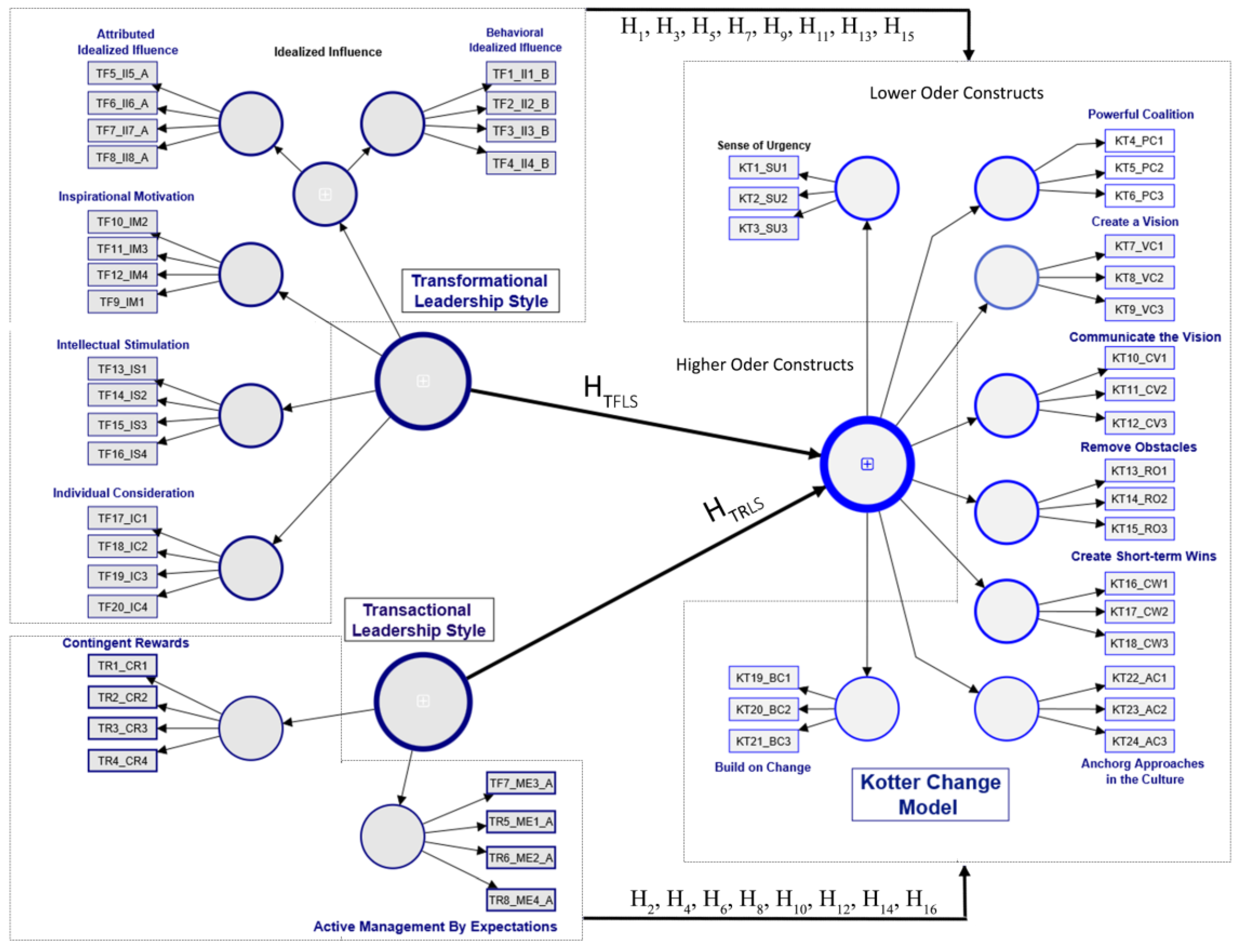

3. Hypotheses and Research Conceptual Model

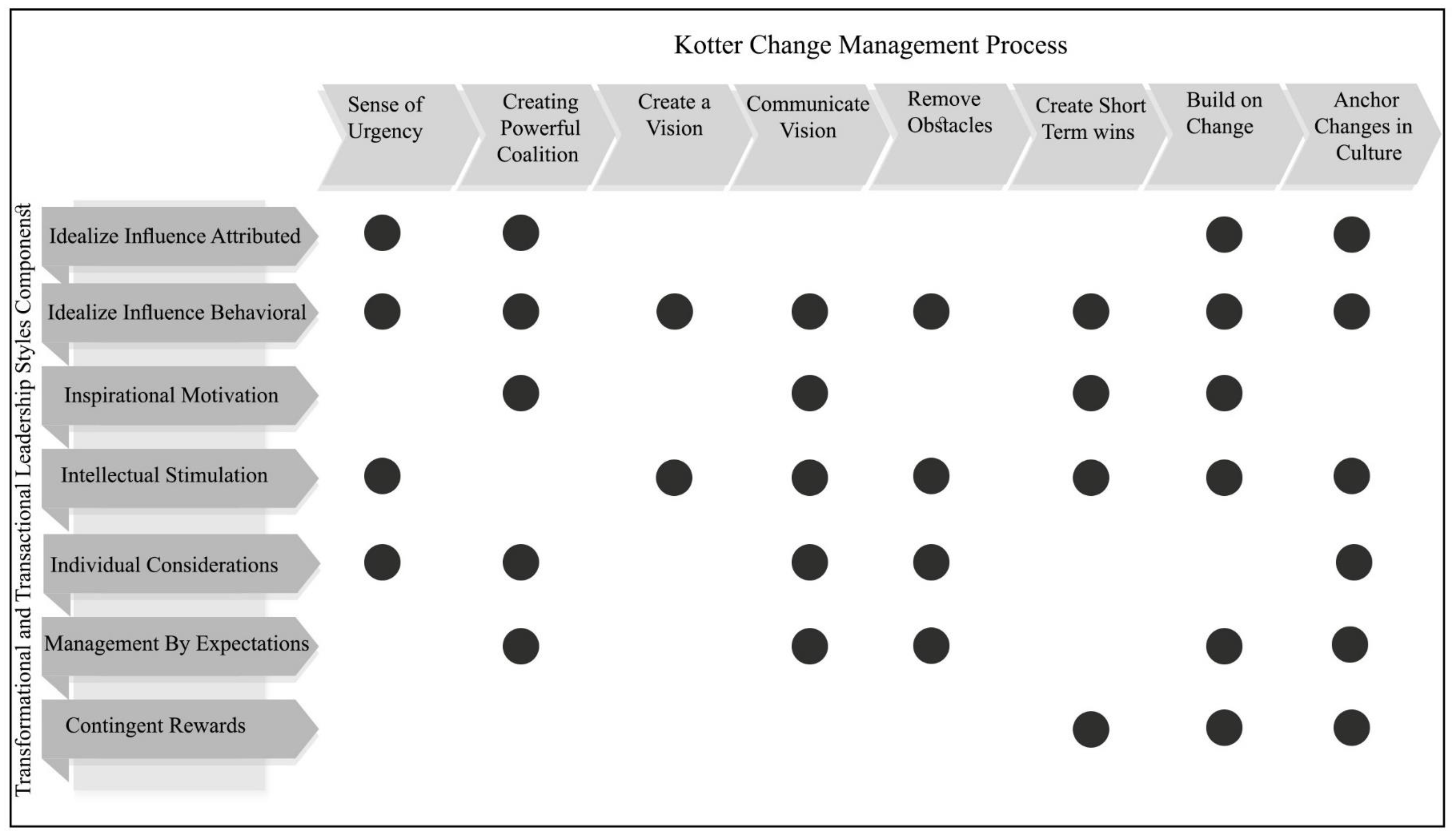

3.1. Leadership Style at the First Change Stage

3.2. Leadership Style at the Second Change Stage

3.3. Leadership Style at the Third Change Stage

3.4. Leadership Style at the Fourth Change Stage

3.5. Leadership Style at the Fifth Change Stage

3.6. Leadership Style at the Sixth Change Stage

3.7. Leadership Style at the Seventh Change Stage

3.8. Leadership Style at the Last Change Stage

4. Methodology

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kotter, J. Change Management vs. Change Leadership—What’s the Difference? 2011. Forbes Online. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkotter/2011/07/12/change-management-vs-change-leadership-whats-the-difference/?sh=7da6a4264cc6 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Anderson, L.A.; Anderson, D. The Change Leader’s Roadmap: How to Navigate Your Organization’s Transformation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 384, ISBN 0470648066. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt, J. ADKAR: A Model for Change in Business, Government and Our Community; Prosci Learning Center Publications: Loveland, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail; Harvard Business Review Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Kurt Lewin in the Clasroom, in the Field, and in Change Theory: Notes toward a Model of Managed Learning; Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, R.J.; Batten, D. It’s just a phase we’re going through: A review and synthesis of OD phase analysis. Gr. Organ. Stud. 1985, 10, 383–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersey, P.; Blanchard, K.H. Management of Organizational Behavior: Utilizing Human Resources; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 1969; p. 10510. [Google Scholar]

- Lippitt, R.; Watson, J.; Westley, B. The Dynamics of Planned Change; Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, E.C.K.; Ko, P.Y. Leadership strategies for creating a Learning Study Community. KEDI J. Educ. Policy 2012, 9, 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis, M. Re-implementing an individual performance management system as a change intervention at higher education Institutions—Overcoming staff resistance. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance, Sophia-Antipolis, France, 6–7 October 2011; pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, J.; Pollack, R. Using Kotter’s Eight Stage Process to Manage an Organisational Change Program: Presentation and Practice. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2014, 28, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I. Organisational quality and organisational change: Interconnecting paths to effectiveness. Libr. Manag. 2011, 32, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.J. Change management in health care. Health Care Manag. 2008, 27, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, W.Z.; Gely, M.I.; Crespo, K.; Matos, J.R.; Sánchez, N.; Guerrero, L.M. Transformation of a dental school’s clinical assessment system through Kotter’s Eight-Step Change process. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 75, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P.; Cohen, D.S. The Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 1422187330. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Effendi, A.A.; Iqbal, Q. The Mechanism Underlying the Sustainable Performance of Transformational Leadership: Organizational Identification as Moderator. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqatawenh, A. Transformational leadership style and its relationship with change management. Bus. Theory Pract. 2018, 19, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.A.A.; Gelaidan, H.; Ahmad, F. New leadership style and lecturers’ commitment in Yemen higher education institutions. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 21, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, D.M.; Fedor, D.B.; Caldwell, S.; Liu, Y. The Effects of Transformational and Change Leadership on Employees’ Commitment to a Change: A Multilevel Study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiherl, J.; Masal, D. Transformational leadership and followers’ commitment to mission changes. Int. J. Public Adm. 2016, 39, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Voet, J.; Groeneveld, S.; Kuipers, B.S. Talking the Talk or Walking the Walk? The Leadership of Planned and Emergent Change in a Public Organization. J. Chang. Manag. 2014, 14, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- der Voet, J.; Kuipers, B.S.; Groeneveld, S. Implementing Change in Public Organizations: The relationship between leadership and affective commitment to change in a public sector context. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 842–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijts, G.H.; Gandz, J. Transformational change and leader character. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berson, Y.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational leadership and the dissemination of organizational goals: A case study of a telecommunication firm. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, M.; Rowland, D. All changes great and small: Exploring approaches to change and its leadership. J. Chang. Manag. 2005, 5, 121–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for individual, team, and organizational development. Res. Organ. Chang. Dev. 1990, 4, 231–272. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 1422186431. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J.P.; Rathgeber, H. Our Iceberg is Melting: Changing and Succeeding under Any Conditions; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 0312368526. [Google Scholar]

- Sverdrup, T.E.; Stensaker, I.G. Restoring trust in the context of strategic change. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 401–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Iñiguez, Á.; Collado-Agudo, J.; Rialp-Criado, J. The Role of Managers in Corporate Change Management: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grint, K. Leadership: Limits and Possibilities; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 1137070587. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, M. The fallacy of misplaced leadership. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1101–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, D.; Hickerson, K.; Pillutla, A. Organizational visioning: An integrative review. Gr. Organ. Manag. 2011, 36, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drath, W.H.; Palus, C.J. Making Common Sense: Leadership as Meaning-Making in a Community of Practice; Center for Creative Leadership: Greensboro, NC, USA, 1994; ISBN 1932973516. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D.; Maccoby, N.; Morse, N.C. Productivity, Supervision, and Morale in an Office Situation. Part I; Institute for Social Research: Oxford, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Stogdill, R.M.; Coons, A.E. Leader behavior: Its description and measurement. Adm. Sci. Q. 1957, 3, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crevani, L.; Lindgren, M.; Packendorff, J. Leadership, not leaders: On the study of leadership as practices and interactions. Scand. J. Manag. 2010, 26, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, J. Leading Change: Overcoming the Ideology of Comfort and the Tyranny of Custom; The Jossey-Bass Management Series; Jossey-Bass Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995; ISBN 1555426085. [Google Scholar]

- Di Schiena, R.; Letens, G.; Van Aken, E.; Farris, J. Relationship between Leadership and Characteristics of Learning Organizations in Deployed Military Units: An Exploratory Study. Adm. Sci. 2013, 3, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkethly, A.; Prosser, M. The first year experience project: A model for university-wide change. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2001, 20, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Coulter, M.A. Management, 14th ed.; Pearson Higher Education FT Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 0134527607. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Bass, R. The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780743215527. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.; Sardais, C. A concept of leadership for strategic organization. Strateg. Organ. 2011, 9, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 0029018102. [Google Scholar]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Visualising the quality and the evolution of transactional and transformation leadership research: A 16-year bibliometric review. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2023, 34, 148–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M. Developing Potential Across a Full Range of Leadership TM: Cases on Transactional and Transformational Leadership; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurgood, K.L. HIC SUNT LEONES: Effective leadership and the challenge of change. Eur. J. Manag. 2015, 15, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaidan, H.M.; Ahmad, H. Employee affective commitment to change, leadership styles and organisational culture: A case of Yemen public sector. In Proceedings of the 16th International Business Information Management Association Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 29–30 June 2011; Volume 4, pp. 2047–2056. [Google Scholar]

- Lirong, L.; Minxin, M. Impact of leadership style on organizational change an empirical study in China. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing, WiCOM, Dalian, China, 12–17 October 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- der Voet, J. The effectiveness and specificity of change management in a public organization: Transformational leadership and a bureaucratic organizational structure. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakucha, W.N. The Role of Charismatic Leadership in Change Management Using Kurt Lewin’s Three Stage Model. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- Bakari, H.; Hunjra, A.I.; Niazi, G.S.K. How Does Authentic Leadership Influence Planned Organizational Change? The Role of Employees’ Perceptions: Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Lewin’s Three Step Model. J. Chang. Manag. 2017, 17, 155–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N.; Wolfram Cox, J.; Tse, H.H.M.; Lowe, K.B. From competency to conversation: A multi-perspective approach to collective leadership development. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, J.H.; Pinkow, F. Leadership for Organisational Adaptability: How Enabling Leaders Create Adaptive Space. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, T.K.; Matthews, S.H.; Breevaart, K. Leading day-to-day: A review of the daily causes and consequences of leadership behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2020, 31, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H. Sustainable development: The colors of sustainable leadership in learning organization. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakhathi, A.; le Roux, C.; Davis, A. Sustainability Leaders’ Influencing Strategies for Institutionalising Organisational Change towards Corporate Sustainability: A Strategy-as-Practice Perspective. J. Chang. Manag. 2019, 19, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alolabi, Y.A.; Ayupp, K.; Dwaikat, M. Al Issues and Implications of Readiness to Change. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raelin, J.A. Toward a methodology for studying leadership-as-practice. Leadership 2020, 16, 480–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, G.J.; Cerni, T. For Leaders to be Transformational, They Must Think Imaginatively. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2015, 9, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, G.J.; King, G.; Russ, A. Reexamining the Relationship Between Thinking Styles and Transformational Leadership: What Is the Contribution of Imagination and Emotionality? J. Leadersh. Stud. 2017, 11, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; House, R.J. Instrumental leadership: Measurement and extension of transformational-transactional leadership theory. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 746–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remund, D. Asking the right questions, involving the right people. The responsibility of corporate communications leaders. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2011, 5, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P.; Schlesinger, L.A. Choosing strategies for change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.; Mitchell, R.; Boyle, B. The Divergent Effects of Transformational Leadership on Individual and Team Innovation. Gr. Organ. Manag. 2016, 41, 66–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, P.J.; Clark, C.M.; Strohfus, P.; Belcheir, M. Using transformational change to improve organizational culture and climate in a school of nursing. J. Nurs. Educ. 2012, 51, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipu, S.A.A.; Ryan, J.C.; Fantazy, K.A. Transformational leadership in Pakistan: An examination of the relationship of transformational leadership to organizational culture and innovation propensity. J. Manag. Organ. 2012, 18, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, G.; Zyphur, M.J. Rituals in organizations: A review and expansion of current theory. Gr. Organ. Manag. 2009, 34, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, W. Lebanon: A History, 600–2011 (Studies in Middle Eastern History); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; ISBN 0190217839. [Google Scholar]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Gig Economy Practices, Ecosystem, and Women’s Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical Model BT—Research and Innovation Forum 2022; Visvizi, A., Troisi, O., Grimaldi, M., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Complexity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Entrepreneurial ecosystem, gig economy practices and Women’s entrepreneurship: The case of Lebanon. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2023, 15, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. MLQ Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Second Edition Sampler Set: Technical Report, Leader Form, Rater Form, and Scoring Key for MLQ Form 5x-Short. 2000. Available online: https://www.mindgarden.com/16-multifactor-leadership-questionnaire (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M.; Jung, D.I. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowold, J.; Heinitz, K. Transformational and charismatic leadership: Assessing the convergent, divergent and criterion validity of the MLQ and the CKS. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models. Long Range Plann. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1483377431. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.K.-K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Fygenson, M. Understanding and predicting electronic commerce adoption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Stogdill, R.M. Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 0029015006. [Google Scholar]

- Holten, A.-L.; Brenner, S.O. Leadership style and the process of organizational change. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 36, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmaghi, E.-E.; Ranf, D.-E.; Badea, D. Interdisciplinary Exploration between Organizational Culture and Sustainable Development Management Applied to the Romanian Higher Education Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, N.A. Employees’ Innovative Work Behavior and Change Management Phases in Government Institutions: The Mediating Role of Knowledge Sharing. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natter, M.; Mild, A.; Feurstein, M.; Dorffner, G.; Taudes, A. The effect of incentive schemes and organizational arrangements on the new product development process. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 1029–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qura’an, A. The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Organizational Change Management: Case Study at Jordan Ahli Bank. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. The role of sustainability in the relationship between migration and smart cities: A bibliometric review. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2021, 23, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. A Bibliometric Review of Smart Cities and Migration BT—Research and Innovation Forum 2020; Springer Proceedings in Complexity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 123–133. [Google Scholar]

| Province | Population | % | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Lebanon | 1,508,720 | 38.08 | 147 |

| North Lebanon | 816,790.00 | 20.6 | 80 |

| South Lebanon | 724,646 | 18.29 | 70 |

| Bekaa | 533,201 | 13.45 | 50 |

| Beirut | 378,464 | 9.5 | 37 |

| Total | 3,961,821.00 | 100% | 385 |

| Construct | Indicator | Loading a | T-Value | CA b | CR c | AVE d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kotter Eight-Step Change Model | KT1_SU1 | Stage 1 | 0.845 | 40.02 ** | 0.842 | 0.904 | 0.759 |

| KT2_SU2 | 0.894 | 80.31 ** | |||||

| KT3_SU3 | 0.874 | 74.67 ** | |||||

| KT4_PC1 | Stage 2 | 0.828 | 37.04 ** | 0.772 | 0.868 | 0.687 | |

| KT5_PC2 | 0.856 | 51.65 ** | |||||

| KT6_PC3 | 0.802 | 30.97 ** | |||||

| KT7_VC1 | Stage 3 | 0.795 | 36.11 ** | 0.732 | 0.849 | 0.652 | |

| KT8_VC2 | 0.828 | 49.16 ** | |||||

| KT9_VC3 | 0.798 | 35.48 ** | |||||

| KT10_CV1 | Stage 4 | 0.793 | 37.83 ** | 0.704 | 0.836 | 0.631 | |

| KT11_CV2 | 0.865 | 64.38 ** | |||||

| KT12_CV3 | 0.718 | 25.43 ** | |||||

| KT13_RO1 | Stage 5 | 0.775 | 29.15 ** | 0.719 | 0.842 | 0.641 | |

| KT14_RO2 | 0.795 | 34.33 ** | |||||

| KT15_RO3 | 0.83 | 39.98 ** | |||||

| KT16_CW1 | Stage 6 | 0.864 | 55.67 ** | 0.767 | 0.866 | 0.683 | |

| KT17_CW2 | 0.824 | 47.88 ** | |||||

| KT18_CW3 | 0.789 | 32.54 ** | |||||

| KT19_BC1 | Stage 7 | 0.729 | 19.9 ** | 0.71 | 0.838 | 0.633 | |

| KT20_BC2 | 0.83 | 43.16 ** | |||||

| KT21_BC3 | 0.824 | 50.34 ** | |||||

| KT22_AC1 | Stage 8 | 0.842 | 52.43 ** | 0.82 | 0.893 | 0.735 | |

| KT23_AC2 | 0.874 | 67.38 ** | |||||

| KT24_AC3 | 0.857 | 50.84 ** | |||||

| Second Order | 0.87 | 0.904 | 0.545 | ||||

| Construct | Indicator | Loading a | T-Value | CA b | CR c | AVE d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational Leadership Style | TF1_II1_B | Idealized Influence Behavior | 0.734 | 24.14 ** | 0.771 | 0.853 | 0.592 |

| TF2_II2_B | 0.789 | 38.41 ** | |||||

| TF3_II3_B | 0.791 | 34.43 ** | |||||

| TF4_II4_B | 0.8 | 37.6 ** | |||||

| TF5_II5_A | Idealized Influence Attribute | 0.842 | 56.16 ** | 0.784 | 0.861 | 0.607 | |

| TF6_II6_A | 0.77 | 28.74 ** | |||||

| TF7_II7_A | 0.744 | 27.92 ** | |||||

| TF8_II8_A | 0.716 | 17.00 ** | |||||

| TF9_IM1 | Inspirational Motivation | 0.801 | 35.74 ** | 0.737 | 0.835 | 0.561 | |

| TF10_IM2 | 0.63 | 14.16 ** | |||||

| TF11_IM3 | 0.759 | 27.23 ** | |||||

| TF12_IM4 | 0.792 | 36.54 ** | |||||

| TF13_IS1 | Intellectual Stimulation | 0.737 | 22.79 ** | 0.723 | 0.828 | 0.547 | |

| TF14_IS2 | 0.734 | 26.38 ** | |||||

| TF15_IS3 | 0.694 | 16.67 ** | |||||

| TF16_IS4 | 0.79 | 38.29 ** | |||||

| TF17_IC1 | Individual Consideration | 0.71 | 21.06 ** | 0.758 | 0.846 | 0.579 | |

| TF18_IC2 | 0.737 | 22.09 ** | |||||

| TF19_IC3 | 0.792 | 35.16 ** | |||||

| TF20_IC4 | 0.8 | 41.16 ** | |||||

| Second order | 0.901 | 0.927 | 0.717 | ||||

| Transactional Leadership Style | TR1_CR1 | Contingent Reward | 0.784 | 35.79 ** | 0.775 | 0.856 | 0.597 |

| TR2_CR2 | 0.755 | 21.87 ** | |||||

| TR3_CR3 | 0.784 | 23.29 ** | |||||

| TR4_CR4 | 0.767 | 21.08 ** | |||||

| TR5_ME1_A | Management By Expectation | 0.783 | 35.29 ** | 0.711 | 0.822 | 0.536 | |

| TR6_ME2_A | 0.725 | 30.24 ** | |||||

| TR7_ME3_A | 0.72 | 37.18 ** | |||||

| TR8_ME4_A | 0.697 | 30.08 ** | |||||

| Second order | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.708 | ||||

| Indicator | Construct | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IIB | IIA | IM | IS | IC | CR | MBEA | SU | PC | VC | CV | RO | CW | BC | AC | |

| TF1_II1_B | 0.73 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.33 |

| TF2_II2_B | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| TF3_II3_B | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.35 |

| TF4_II4_B | 0.80 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.34 |

| TF5_II5_A | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.41 |

| TF6_II6_A | 0.54 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.33 |

| TF7_II7_A | 0.55 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.27 |

| TF8_II8_A | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.26 |

| TF9_IM1 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.80 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| TF10_IM2 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.65 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| TF11_IM3 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.76 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.32 |

| TF12_IM4 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| TF13_IS1 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.34 |

| TF14_IS2 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| TF15_IS3 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.36 |

| TF16_IS4 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.32 |

| TF17_IC1 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| TF18_IC2 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.74 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| TF19_IC3 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| TF20_IC4 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| TR1_CR1 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.78 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.23 |

| TR2_CR2 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| TR3_CR3 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| TR4_CR4 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.77 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| TR5_ME1_A | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.78 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.38 |

| TR6_ME2_A | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| TR7_ME3_A | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.72 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| TR8_ME4_A | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

| KT1_SU1 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.85 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.22 |

| KT2_SU2 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.89 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| KT3_SU3 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| KT4_PC1 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.83 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.37 |

| KT5_PC2 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.86 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.29 |

| KT6_PC3 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.80 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.26 |

| KT7_VC1 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.39 |

| KT8_VC2 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.37 |

| KT9_VC3 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.36 |

| KT10_CV1 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.79 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.44 |

| KT11_CV2 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.87 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.46 |

| KT12_CV3 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.42 |

| KT13_RO1 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.78 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.51 |

| KT14_RO2 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.48 |

| KT15_RO3 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.83 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| KT16_CW1 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.86 | 0.50 | 0.46 |

| KT17_CW2 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.44 |

| KT18_CW3 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.59 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.79 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| KT19_BC1 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.30 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.73 | 0.40 |

| KT20_BC2 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.83 | 0.66 |

| KT21_BC3 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.82 | 0.52 |

| KT22_AC1 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.84 |

| KT23_AC2 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.71 | 0.87 |

| KT24_AC3 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.86 |

| Indicator | Construct | Transformational Leadership Style | Transactional Leadership Style | Kotter Change Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TF1 till TF20 | IIA | 0.862 | 0.55 | 0.523 |

| IIB | 0.892 | 0.605 | 0.575 | |

| IC | 0.834 | 0.68 | 0.525 | |

| IS | 0.809 | 0.665 | 0.557 | |

| IM | 0.835 | 0.555 | 0.456 | |

| TR1 till TR8 | MBEA | 0.591 | 0.859 | 0.448 |

| CR | 0.63 | 0.823 | 0.403 | |

| KT1 till KT24 | SU | 0.337 | 0.327 | 0.559 |

| PC | 0.458 | 0.388 | 0.651 | |

| VC | 0.44 | 0.325 | 0.721 | |

| CV | 0.46 | 0.403 | 0.815 | |

| RO | 0.496 | 0.405 | 0.76 | |

| CW | 0.411 | 0.345 | 0.753 | |

| BC | 0.56 | 0.402 | 0.833 | |

| AC | 0.494 | 0.384 | 0.774 |

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Active Management by Expectations | 0.73 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Anchoring Approaches in Culture | 0.36 | 0.86 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Attributed Idealized Influence | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.77 | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | Behavioral Idealized Influence | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.71 | 0.78 | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | Build on Change | 0.37 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.80 | |||||||||||||

| 6 | Communicate the Vision | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.79 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Contingent Rewards | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.77 | |||||||||||

| 8 | Create Short-Term Wins | 0.29 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.83 | ||||||||||

| 9 | Create a Vision | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 0.26 | 0.41 | 0.81 | |||||||||

| 10 | Individual Consideration | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.66 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.76 | ||||||||

| 11 | Inspirational Motivation | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.75 | |||||||

| 12 | Intellectual Stimulation | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.74 | ||||||

| 13 | Powerful Coalition | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.83 | |||||

| 14 | Remove Obstacles | 0.38 | 0.58 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.80 | ||||

| 15 | Sense of Urgency | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.87 | |||

| 16 | Kotter Change Model | Second Order Model Discriminant Validity | 0.74 | ||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Transactional Leadership Style | 0.51 | 0.84 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18 | Transformational Leadership Style | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.85 | |||||||||||||||

| IIA | IIB | IC | IM | IS | Transformational Leadership Style | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyp. | Std. β | T | p | Hyp. | Std. β | T | p | Hyp. | Std. β | T | p | Hyp. | Std. β | T | p | Hyp. | Std. β | T Value | p | Hyp. | Std. β | T | F2 | p | |

| SU | H1A | 0.14 | 1.58 * | 0.05 | H1B | 0.12 | 1.4 * | 0.05 | H1C | 0.10 | 1.15 | 0.13 | H1D | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.21 | H1E | 0.14 | 1.56 * | 0.05 | H1 | 0.34 | 7.1 ** | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| PC | H3A | 0.26 | 3.1 ** | 0.00 | H3B | 0.10 | 1.3 * | 0.04 | H3C | 0.25 | 3.1 ** | 0.00 | H3D | 0.21 | 2.7 ** | 0.00 | H3E | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.36 | H3 | 0.46 | 9.5 ** | 0.26 | 0.00 |

| VC | H5A | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.23 | H5B | 0.20 | 2.3 ** | 0.01 | H5C | 0.04 | 0.70 | 0.24 | H5D | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.48 | H5E | 0.22 | 3.2 ** | 0.00 | H5 | 0.44 | 9.8 ** | 0.24 | 0.00 |

| CV | H7A | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.33 | H7B | 0.24 | 2.9 ** | 0.00 | H7C | 0.13 | 1.9 * | 0.03 | H7D | 0.12 | 1.70 * | 0.04 | H7E | 0.17 | 2.4 ** | 0.01 | H7 | 0.46 | 10.6 ** | 0.26 | 0.00 |

| RO | H9A | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.18 | H9B | 0.13 | 1.5 * | 0.05 | H9C | 0.12 | 2.0 ** | 0.02 | H9D | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.35 | H9E | 0.24 | 3.5 ** | 0.00 | H9 | 0.49 | 12.4 ** | 0.32 | 0.00 |

| CW | H11A | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.42 | H11B | 0.25 | 2.6 ** | 0.01 | H11C | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.25 | H11D | 0.11 | 1.70 * | 0.04 | H11E | 0.12 | 1.71 * | 0.04 | H11 | 0.41 | 8.8 ** | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| BC | H13A | 0.25 | 3.7 ** | 0.00 | H13B | 0.29 | 3.9 ** | 0.00 | H13C | 0.04 | 0.55 | 0.29 | H13D | 0.14 | 2.2 ** | 0.01 | H13E | 0.29 | 4.6 ** | 0.00 | H13 | 0.56 | 15 ** | 0.45 | 0.00 |

| AC | H15A | 0.11 | 1.5 * | 0.05 | H15B | 0.30 | 3.4 ** | 0.00 | H15C | 0.20 | 2.3 ** | 0.02 | H15D | 0.09 | 1.04 | 0.15 | H15E | 0.16 | 2.7 ** | 0.00 | H15 | 0.49 | 12.4 ** | 0.32 | 0.00 |

| HTFLS: Transformational Leadership → Kotter Change Model | Std. β | Std. Error | T-Value | p Values | Decision | F2 | 2.5% CI LL | 97.5% CI UL |

| 0.543 | 0.05 | 10.097 ** | 0.00 | Supported ** | 0.647 | 0.44 | 0.65 |

| MBA | CR | Transactional Leadership Style | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyp. | Std. β | T Value | p Values | Hyp. | Std. β | T Value | p Values | Hyp. | Std. β | T Value | F2 | p Values | |

| SU | H1A | 0.063 | 1.001 | 0.159 | H1B | 0.094 | 1.256 | 0.105 | H2 | 0.376 | 8.3 ** | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| PC | H4A | 0.104 | 1.617 * | 0.050 | H4B | 0.017 | 0.185 | 0.427 | H4 | 0.388 | 8.2 ** | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| VC | H6A | 0.027 | 0.426 | 0.335 | H7B | 0.032 | 0.517 | 0.303 | H6 | 0.324 | 6.5 ** | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| CV | H8A | 0.124 | 2.24 ** | 0.013 | H8B | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.485 | H8 | 0.401 | 9.04 ** | 0.19 | 0.00 |

| RO | H10A | 0.119 | 2.16 ** | 0.015 | H10B | 0.05 | 0.901 | 0.184 | H10 | 0.398 | 9.2 * | 0.19 | 0.00 |

| CW | H12A | 0.067 | 1.04 | 0.149 | H12B | 0.076 | 1.47 * | 0.046 | H12 | 0.344 | 7.42 ** | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| BC | H14A | 0.073 | 1.44 * | 0.045 | H14B | 0.093 | 1.59 * | 0.049 | H14 | 0.398 | 8.7 ** | 0.19 | 0.00 |

| AC | H16A | 0.113 | 2.12 ** | 0.017 | H16B | 0.067 | 1.05 * | 0.050 | H16 | 0.327 | 7.1 ** | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| HTRLS: Transactional Style -> Kotter Change Model | Std. β | Std. Error | T-Value | p Values | Decision | F2 | 2.5% CI LL | 97.5% CI UL |

| 0.119 | 0.05 | 2.006 * | 0.045 | Supported * | 0.258 | 0.013 | 0.227 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mouazen, A.M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B.; Abdallah, F.; Ramadan, M.; Chahine, J.; Baydoun, H.; Bou Zakhem, N. Transformational and Transactional Leaders and Their Role in Implementing the Kotter Change Management Model Ensuring Sustainable Change: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010016

Mouazen AM, Hernández-Lara AB, Abdallah F, Ramadan M, Chahine J, Baydoun H, Bou Zakhem N. Transformational and Transactional Leaders and Their Role in Implementing the Kotter Change Management Model Ensuring Sustainable Change: An Empirical Study. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMouazen, Ali M., Ana Beatriz Hernández-Lara, Farid Abdallah, Muhieddine Ramadan, Jawad Chahine, Hala Baydoun, and Najib Bou Zakhem. 2024. "Transformational and Transactional Leaders and Their Role in Implementing the Kotter Change Management Model Ensuring Sustainable Change: An Empirical Study" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010016

APA StyleMouazen, A. M., Hernández-Lara, A. B., Abdallah, F., Ramadan, M., Chahine, J., Baydoun, H., & Bou Zakhem, N. (2024). Transformational and Transactional Leaders and Their Role in Implementing the Kotter Change Management Model Ensuring Sustainable Change: An Empirical Study. Sustainability, 16(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010016