Bibliometric Review on Sustainable Finance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- 1

- Set the search process to:

- (i)

- Identify the bibliographic database and incorporate the relevant keywords into a logical search statement;

- (ii)

- Introduce the relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria to narrow down the scope of literature coverage and derive the final dataset for our review.

- 2

- Conduct the bibliometric analysis:

- (i)

- Carry out a bibliometric performance analysis (BPA) to determine the most important research constituents of sustainable finance literature. To do so, we use the citation analysis method available on VOSviewer;

- (ii)

- Perform a bibliometric network analysis (BNA) to figure out the intellectual, social, and conceptual structures of sustainable finance literature.

- 3

- Apply a content analysis process to our dataset to identify and investigate the key research themes in the literature on sustainable finance.

2.1. Set the Search Process

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis

2.3. Content Analysis

3. Bibliometric Performance Analysis (BPA)

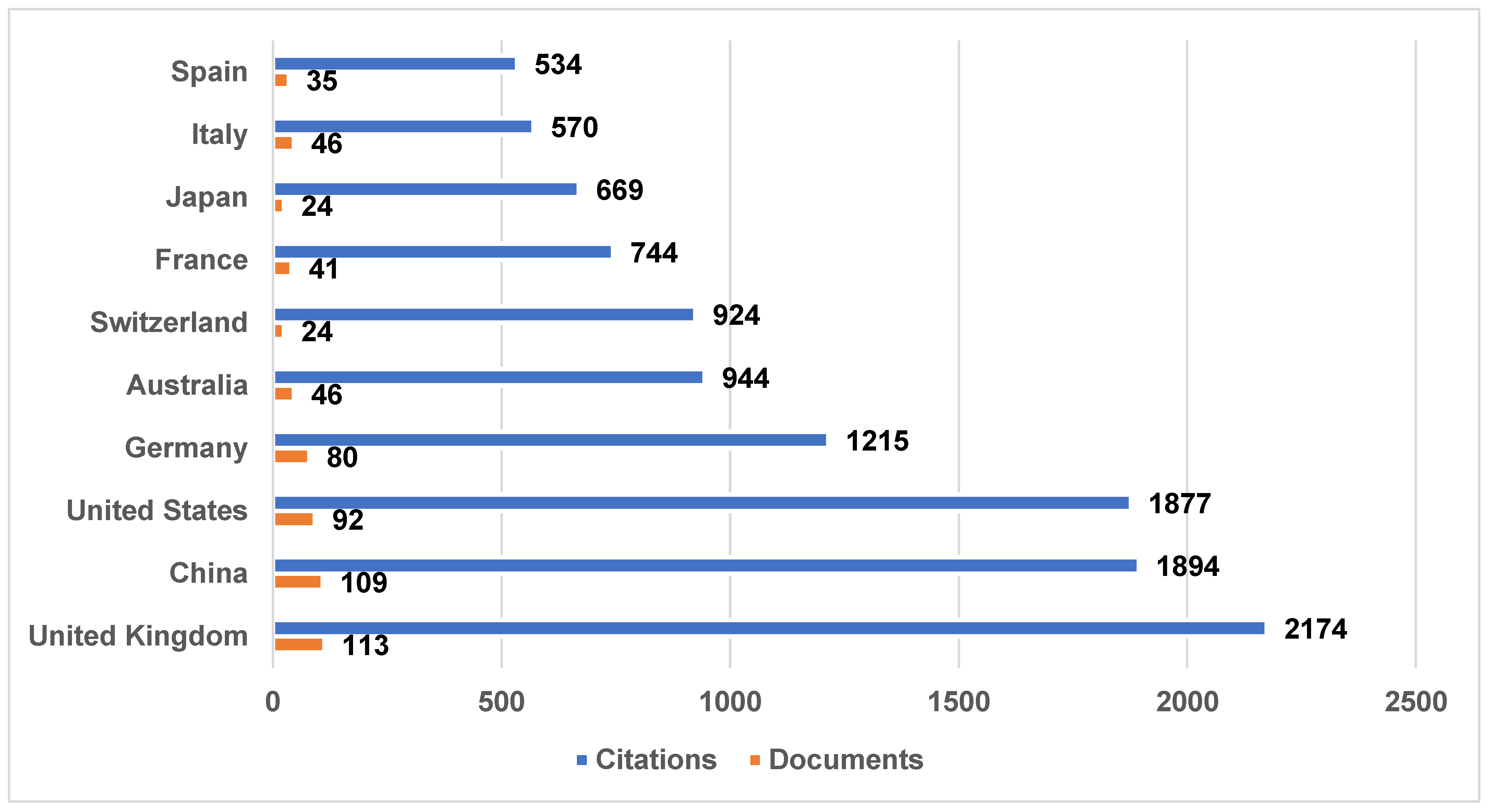

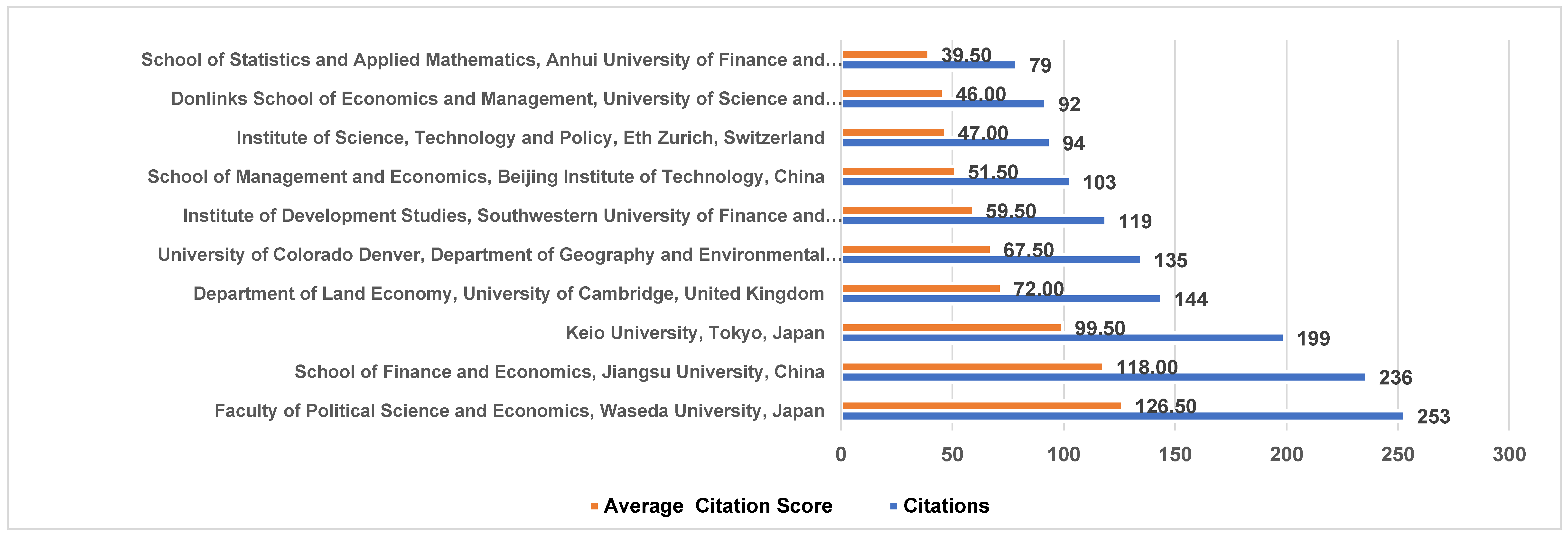

3.1. Most Influential Countries and Institutions

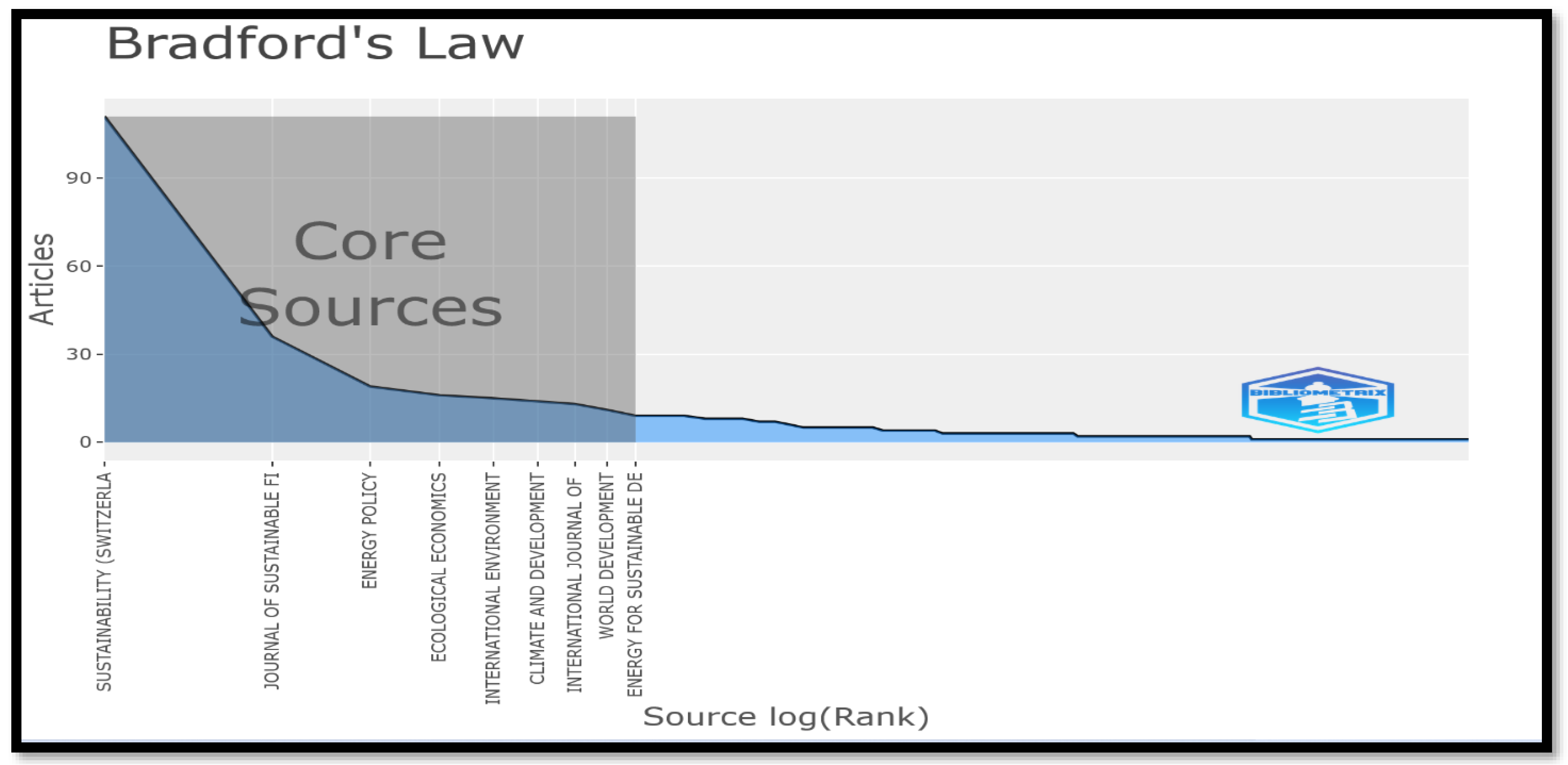

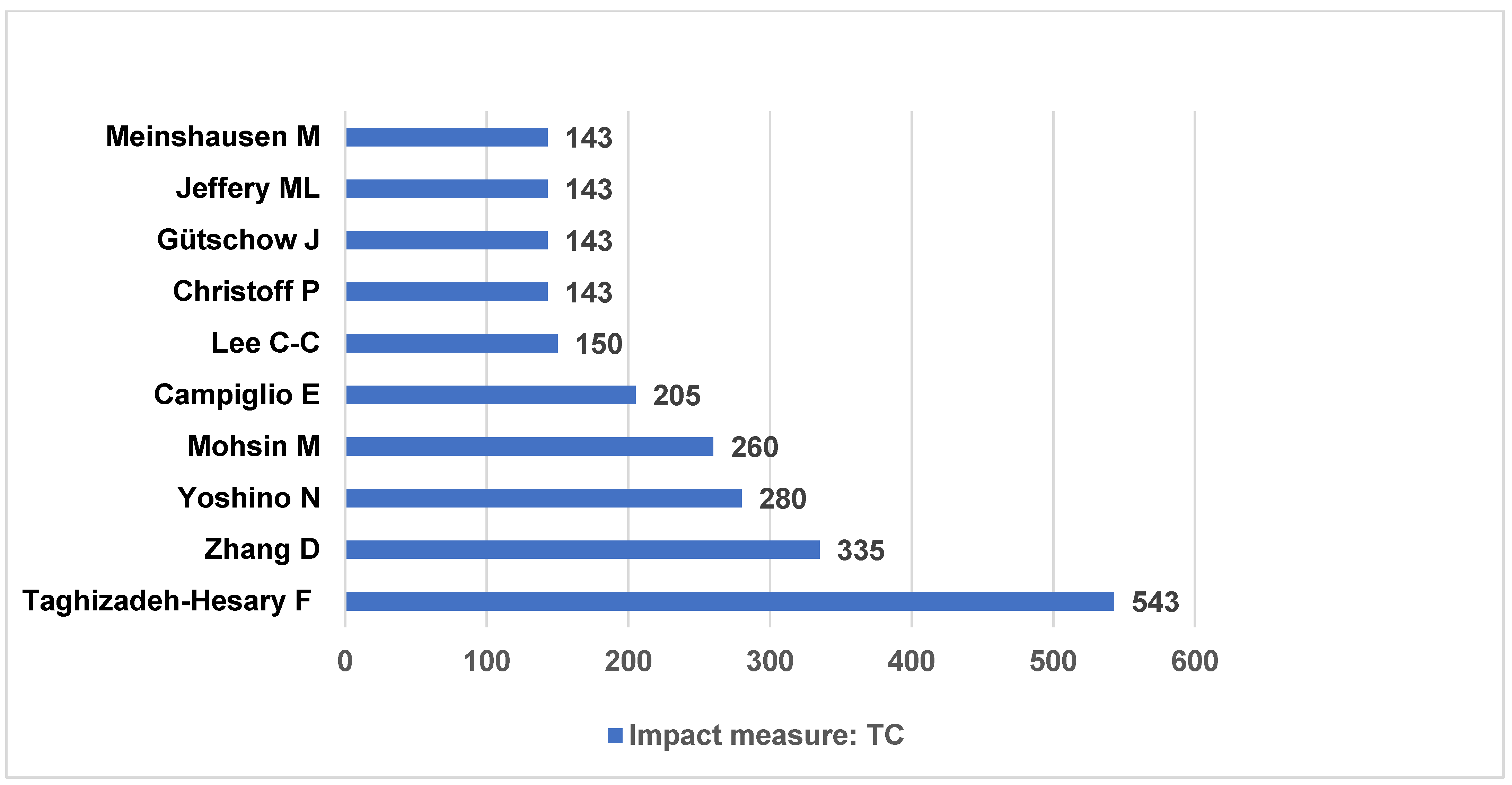

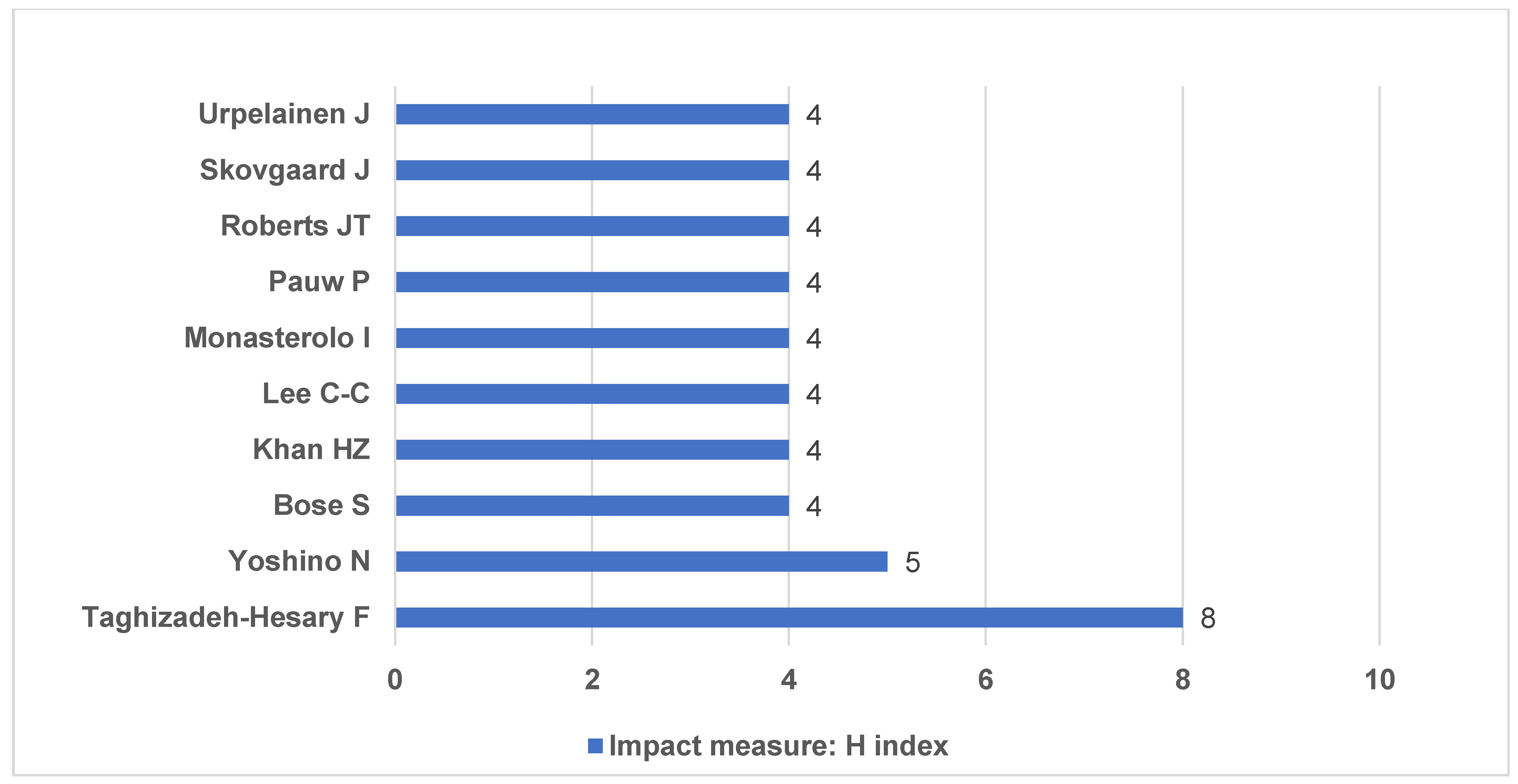

3.2. Most Influential Journals and Authors

3.3. Most Influential Articles

4. Bibliometric Network Map Analysis (BNA)

4.1. Intellectual Structure (Co-Citation Analysis)

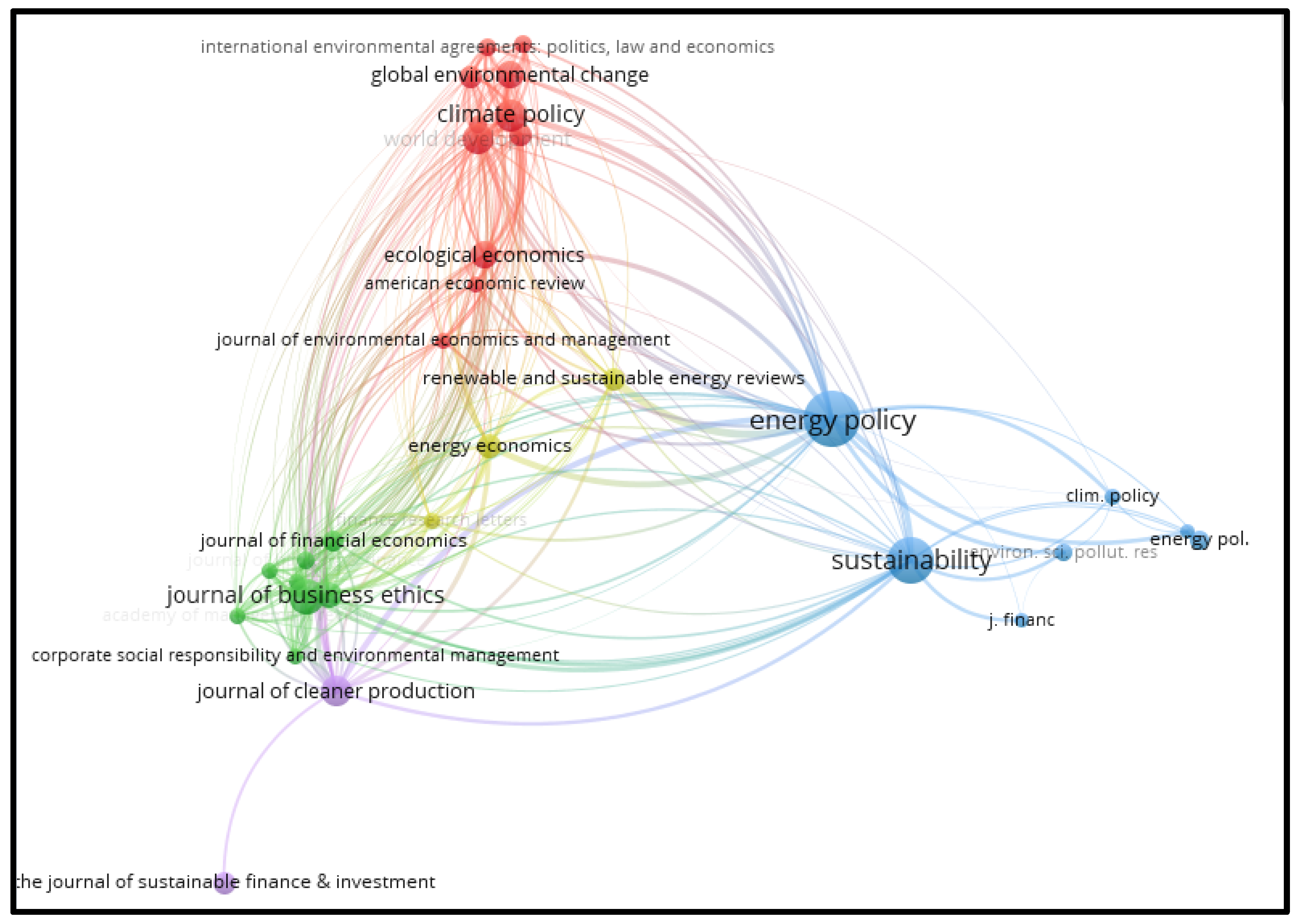

Co-Citation of Sources

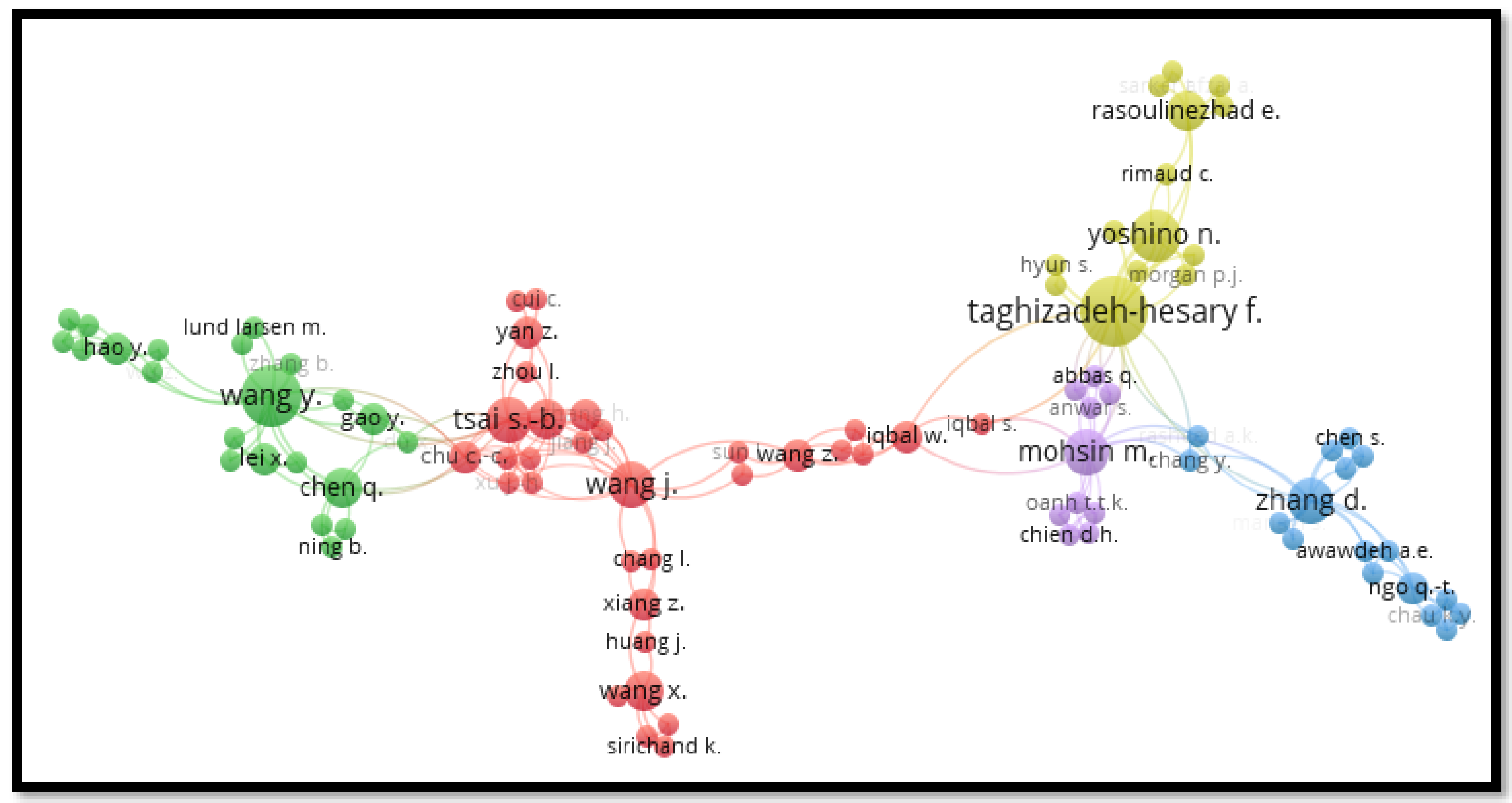

4.2. Social Structure (Co-Authorship Analysis)

4.3. Conceptual Structure of Sustainable Finance Literature

4.3.1. Bibliographic Coupling

4.3.2. Title and Abstract Map Analysis

4.3.3. Thematic Map Analysis

5. Content Analysis

5.1. Determinants of Banks’ Adoption of Sustainability Practices

5.2. Risk Profile of Sustainable Banks

5.3. Sustainability Performance—Banks’ Profitability Associations

5.4. Macroprudential Regulations, Supervisory Guidelines, and Monetary Policies

5.5. Depositors’/Customers’ Behaviour in Response to Banks’ Sustainability Practices

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors | Title | Source Title |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (Green finance–Energy finance), 69 publications | ||

| Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino, 2019 [40] | The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment | Finance Research Letters |

| Zhang D et al., 2021 [43] | Public spending and green economic growth in BRI region: Mediating role of green finance | Energy Policy |

| He et al., 2019 [87] | Can green financial development promote renewable energy investment efficiency? A consideration of bank credit | Renewable Energy |

| Song et al., 2021 [88] | Impact of green credit on high-efficiency utilization of energy in China considering environmental constraints | Energy Policy |

| Yoshino et al., 2019 [89] | Modelling the social funding and spill-over tax for addressing the green energy financing gap | Economic Modelling |

| Tan et al., 2020 [90] | How connected is the carbon market to energy and financial markets? A systematic analysis of spillovers and dynamics | Energy Economics |

| Azhgaliyeva et al., 2020 [91] | Green bonds for financing renewable energy and energy efficiency in South-East Asia: a review of policies | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment |

| Setyowati, 2020 [92] | Mitigating energy poverty: Mobilizing climate finance to manage the energy trilemma in Indonesia | Sustainability (Switzerland) |

| Jin et al., 2021 [93] | The financing efficiency of listed energy conservation and environmental protection firms: Evidence and implications for green finance in China | Energy Policy |

| Setyowati, 2021 [94] | Mitigating inequality with emissions? Exploring energy justice and financing transitions to low-carbon energy in Indonesia | Energy Research and Social Science |

| Bourcet and Bovari, 2020 [95] | Exploring citizens’ decision to crowdfund renewable energy projects: Quantitative evidence from France | Energy Economics |

| Li et al., 2021 [96] | Renewable energy resources investment and green finance: Evidence from China | Resources Policy |

| Wang F et al., 2021 [97] | The impact of environmental pollution and green finance on the high-quality development of energy based on spatial Dubin model | Resources Policy |

| Cluster 2 (Sustainable and Green Banking), 63 publications | ||

| Cui et al., 2018 [37] | The impact of green lending on credit risk in China | Sustainability (Switzerland) |

| Bose et al., 2018 [10] | What drives green banking disclosure? An institutional and corporate governance perspective | Asia Pacific Journal of Management |

| Sun et al., 2020 [80] | CSR, co-creation, and green consumer loyalty: Are green banking initiatives important? A moderated mediation approach from an emerging economy | Sustainability (Switzerland) |

| Bose et al., 2021 [98] | Does green banking performance pay off? Evidence from a unique regulatory setting in Bangladesh | Corporate Governance: An International Review |

| Khan H.Z et al., 2021 [99] | “Green washing” or “authentic effort”? An empirical investigation of the quality of sustainability reporting by banks | Accounting, Auditing, and Accountability Journal |

| Contreras et al., 2019 [100] | Self-regulation in sustainable finance: The adoption of the Equator Principles | World Development |

| Igbudu et al., 2018 [79] | Enhancing bank loyalty through sustainable banking practices: The mediating effect of corporate image | Sustainability (Switzerland) |

| Ibe-enwo et al., 2019 [78] | Assessing the relevance of green banking practice on bank loyalty: The mediating effect of green image and bank trust | Sustainability (Switzerland) |

| Rehman et al., 2021 [101] | Adoption of green banking practices and environmental performance in Pakistan: a demonstration of structural equation modelling | Environment, Development and Sustainability |

| Amidjaya and Widagdo, 2020 [65] | Sustainability reporting in Indonesian listed banks: Do corporate governance, ownership structure, and digital banking matter? | Journal of Applied Accounting Research |

| Tan et al., 2017 [64] | A holistic perspective on sustainable banking operating system drivers: A case study of the Maybank group | Qualitative Research in Financial Markets |

| Taneja and Ali 2021 [83] | Determinants of customers’ intentions towards environmentally sustainable banking: Testing the structural model | Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services |

| Bryson et al., 2016 [82] | Antecedents of Intention to Use Green Banking Services in India | Strategic Change |

| Khan H.Z et al., 2021 [102] | Green banking disclosure, firm, and the moderating role of a contextual factor: Evidence from a distinctive regulatory setting | Business Strategy and the Environment |

| Cluster 3 (Green finance = Carbon finance = Energy finance), 59 publications | ||

| Bolton and Foxon, 2015 [103] | A socio-technical perspective on low carbon investment challenges—Insights for UK energy policy | Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions |

| Chaurey and Kandpal, 2009 [104] | Carbon abatement potential of solar home systems in India and their cost reduction due to carbon finance | Energy Policy |

| Lambe et al., 2015 [105] | Can carbon finance transform household energy markets? A review of cookstove projects and programs in Kenya | Energy Research and Social Science |

| Maltais and Nykvist, 2021 [106] | Understanding the role of green bonds in advancing sustainability | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment |

| Nakhooda, 2011 [107] | Asia, the Multilateral Development Banks and Energy Governance | Global Policy |

| Zhang B., Wang Y, 2021 [108] | The Effect of Green Finance on Energy Sustainable Development: A Case Study in China | Emerging Markets Finance and Trade |

| Zhang M et al., 2020 [109] | Unlocking green financing for building energy retrofit: A survey in the western China | Energy Strategy Reviews |

| Aglietta et al., 2015 [110] | Financing transition in an adverse context: climate finance beyond carbon finance | International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law, and Economics |

| Chevallier et al., 2021 [111] | Green finance and the restructuring of the oil-gas-coal business model under carbon asset stranding constraints | Energy Policy |

| Cluster 4 (Central bank mandates, relevant macroprudential regulations, and monetary policies for energy finance), 43 publications | ||

| Campiglio, 2016 [5] | Beyond carbon pricing: The role of banking and monetary policy in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy | Ecological Economics |

| Banga, 2019 [112] | The green bond market: a potential source of climate finance for developing countries | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment |

| D’Orazio and Popoyan, 2019 [4] | Fostering green investments and tackling climate-related financial risks: Which role for macroprudential policies? | Ecological Economics |

| Dikau and Volz, 2021 [113] | Central bank mandates, sustainability objectives, and the promotion of green finance | Ecological Economics |

| Raberto et al., 2019 [56] | From financial instability to green finance: the role of banking and credit market regulation in the Eurace model | Journal of Evolutionary Economics |

| Cabré et al., 2018 [114] | Renewable Energy: The Trillion Dollar Opportunity for Chinese Overseas Investment | China and World Economy |

| Durrani et al., 2020 [115] | The role of central banks in scaling up sustainable finance—what do monetary authorities in the Asia-Pacific region think? | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment |

| Roncoroni et al., 2021 [116] | Climate risk and financial stability in the network of banks and investment funds | Journal of Financial Stability |

| Chenet et al., 2021 [117] | Finance, climate-change, and radical uncertainty: Towards a precautionary approach to financial policy | Ecological Economics |

| Monasterolo et al., 2018 [118] | Climate Transition Risk and Development Finance: A Carbon Risk Assessment of China’s Overseas Energy Portfolios | China and World Economy |

| Corrocher and Cappa, 2020 [119] | The role of public interventions in inducing private climate finance: An empirical analysis of the solar energy sector | Energy Policy |

| Esposito et al., 2019 [57] | Environment–risk-weighted assets: allowing banking supervision and green economy to meet for good | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment |

| Matthäus and Mehling, 2020 [120] | De-risking Renewable Energy Investments in Develop ing Countries: A Multilateral Guarantee Mechanism | Joule |

| Gunningham, 2020 [12] | A quiet revolution: Central banks, financial regulators, and climate finance | Sustainability (Switzerland) |

| Cluster 5 (Climate finance), 42 publications | ||

| Weiler et al., 2018 [121] | Vulnerability, good governance, or donor interests? The allocation of aid for climate change adaptation | World Development |

| Betzold and Weiler, 2017 [122] | Allocation of aid for adaptation to climate change: Do vulnerable countries receive more support? | International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law, and Economics |

| Cui and Huang Y, 2018 [123] | Exploring the Schemes for Green Climate Fund Financing: International Lessons | World Development |

| Roberts and Weikmans, 2017 [124] | Postface: fragmentation, failing trust, and enduring tensions over what counts as climate finance | International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law, and Economics |

| Pickering et al., 2015 [125] | Acting on climate finance pledges: Inter-agency dynamics and relationships with aid in contributor states | World Development |

| Remling and Persson, 2015 [126] | Who is adaptation for? Vulnerability and adaptation benefits in proposals approved by the UNFCCC Adaptation Fund | Climate and Development |

| Stadelmann et al., 2011 [127] | New and additional to what? Assessing options for baselines to assess climate finance pledges | Climate and Development |

| Gampfer et al., 2014 [128] | Obtaining public support for North–South climate funding: Evidence from conjoint experiments in donor countries | Global Environmental Change |

| Glomsrød and Wei, 2018 [129] | Business as unusual: The implications of fossil divestment and green bonds for financial flows, economic growth, and energy market | Energy for Sustainable Development |

| Hall, 2017 [130] | What is adaptation to climate change? Epistemic ambiguity in the climate finance system | International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law, and Economics |

| Fankhauser, 2016 [3] | Where are the gaps in climate finance? | Climate and Development |

References

- Naidoo, C.P. Relating Financial Systems to Sustainability Transitions: Challenges, Demands and Dimensions. SSRN Paper. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3443551 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Migliorelli, M. What do we mean by sustainable finance? Assessing existing frameworks and policy risks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, S.; Sahni, A.; Savvas, A.; Ward, J. Where are the gaps in climate finance? Clim. Dev. 2016, 8, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, P.; Popoyan, L. Fostering green investments and tackling climate-related financial risks: Which role for macroprudential policies? Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campiglio, E. Beyond carbon pricing: The role of banking and monetary policy in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S.; Jones, A.; Anger-Kraavi, A.; Pohl, J. Closing the green finance gap–A systems perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 34, 26–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterolo, I.; Roventini, A.; Foxon, T.J. Uncertainty of climate policies and implications for economics and finance: An evolutionary economics approach. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 163, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolo, M.; Filipiak, B.Z.; Bąk, I.; Cheba, K. How to design more sustainable financial systems: The roles of environmental, social, and governance factors in the decision-making process. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, T. What are the determinants for financial institutions to mobilise climate finance? J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2019, 9, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Khan, H.Z.; Rashid, A.; Islam, S. What drives green banking disclosure? An institutional and corporate governance perspective. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 501–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T. Reforming Islamic Finance for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. J. King Abdulaziz Univ. Islam. Econ. 2019, 32. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3465564 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Gunningham, N. A quiet revolution: Central banks, financial regulators, and climate finance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshater, M.M.; Hassan, M.K.; Rashid, M.; Hasan, R. A bibliometric review of the Waqf literature. Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2022, 12, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Meng, F.; Gu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Farrukh, M. Mapping and clustering analysis on environmental, social and governance field a bibliometric analysis using Scopus. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobanee, H.; Al Hamadi, F.Y.; Abdulaziz, F.A.; Abukarsh, L.S.; Alqahtani, A.F.; AlSubaey, S.K.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Almansoori, H.A. A bibliometric analysis of sustainability and risk management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Sharma, D. Evolution of green finance and its enablers: A bibliometric analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Managi, S. A bibliometric analysis on green finance: Current status, development, and future directions. Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 29, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Tian, Z.; Zhong, S.; Lyu, Q.; Deng, M. Global Evolution of Research on Sustainable Finance from 2000 to 2021: A Bibliometric Analysis on WoS Database. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.A.; Karim, S.; Rabbani, M.R.; Bashar, A.; Kumar, S. Current state and future directions of green and sustainable finance: A bibliometric analysis. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/ (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Available online: https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance/the-principles-guidelines-and-handbooks/green-bond-principles-gbp/ (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/2022/11/green-bond-market-hits-usd2tn-milestone-end-q3-2022 (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Khamis, M.S.; Aysan, A.F. Bibliometric Analysis of Green Bonds. In Eurasian Business and Economics Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Cortellini, G.; Panetta, I.C. Green Bond: A Systematic Literature Review for Future Research Agendas. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Inacio, L.; Delai, I. Sustainable banking: A systematic review of concepts and measurements. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Adeabah, D.; Ofosu, D.; Tenakwah, E.J. A review of studies on green finance of banks, research gaps and future directions. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 12, 1241–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secinaro, S.; Calandra, D.; Petricean, D.; Chmet, F. Social finance and banking research as a driver for sustainable development: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2020, 13, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera-Sánchez, J.J. A systematic review of sustainable banking through a co-word analysis. Sustainability 2019, 12, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, J.; Schotten, M.; Plume, A.; Côté, G.; Karimi, R. Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aracil, E.; Nájera-Sánchez, J.J.; Forcadell, F.J. Sustainable banking: A literature review and integrative framework. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 42, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meline, T. Selecting studies for systemic review: Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Contemp. Issues Commun. Sci. Disord. 2006, 33, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual; Univeristeit Leiden: Leiden, Netherlands, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://bibliometrix.org/biblioshiny/biblioshiny3.html (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Available online: https://bibliometrix.org/biblioshiny/assets/player/KeynoteDHTMLPlayer.html#93 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Cui, Y.; Geobey, S.; Weber, O.; Lin, H. The impact of green lending on credit risk in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PBC. China Monetary Policy Report Quarter Three; Monetary Policy Analysis Group of the People’s Bank of China: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford’s Law Ascertains That: “If the Journals are Arranged in Descending Order of the Number of Articles They Carried on the Subject, Then Successive Zones of Periodicals Containing the Same Number of Articles on the Subject form the Simple Geometric Series 1:n:n2:n3”. Available online: https://bibliometrix.org/biblioshiny/assets/player/KeynoteDHTMLPlayer.html#51 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Yoshino, N. The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment. Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 31, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Pont, Y.R.; Jeffery, M.L.; Gütschow, J.; Rogelj, J.; Christoff, P.; Meinshausen, M. Equitable mitigation to achieve the Paris Agreement goals. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.D.; Phelps, J.; Yuen, J.Q.; Webb, E.L.; Lawrence, D.; Fox, J.M.; Bruun, T.B.; Leisz, S.J.; Ryan, C.M.; Dressler, W.; et al. Carbon outcomes of major land-cover transitions in SE Asia: Great uncertainties and REDD + policy implications. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012, 18, 3087–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Mohsin, M.; Rasheed, A.K.; Chang, Y.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Public spending and green economic growth in BRI region: Mediating role of green finance. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle-Blancard, G.; Monjon, S. The performance of socially responsible funds: Does the screening process matter? Eur. Financ. Manag. 2014, 20, 494–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.I. The evolving role of carbon finance in promoting renewable energy development in China. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2875–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Panthamit, N.; Anwar, S.; Abbas, Q.; Vo, X.V. Developing low carbon finance index: Evidence from developed and developing economies. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 43, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, M.; Yang, C. Green credit, green stimulus, green revolution? China’s mobilization of banks for environ-mental cleanup. J. Environ. Dev. 2010, 19, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.H.; Yang, C. The intellectual development of the technology acceptance model: A co-citation analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Chen, W. Political Discourse and Translation Studies. A Bibliometric Analysis in International Core Journals. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221082142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E. Who is the best connected scientist? A study of scientific coauthorship networks. In Complex Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 337–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. Co-authorship networks: A review of the literature. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 67, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho VJ, P.D. Bibliographic Coupling Links: Alternative Approaches to Carrying Out Systematic Reviews about Renewable and Sustainable Energy. Environments 2022, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.A. Mapping the field of arts-based management: Bibliographic coupling and co-citation analyses. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Abdollahi, A.; Treiblmaier, H. The big picture on Instagram research: Insights from a bibliometric analysis. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 73, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafermos, Y.; Nikolaidi, M.; Galanis, G. Climate change, financial stability and monetary policy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 152, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raberto, M.; Ozel, B.; Ponta, L.; Teglio, A.; Cincotti, S. From financial instability to green finance: The role of banking and credit market regulation in the Eurace model. J. Evol. Econ. 2019, 29, 429–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, L.; Mastromatteo, G.; Molocchi, A. Environment–risk-weighted assets: Allowing banking supervision and green economy to meet for good. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2019, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, M. Breaking the tragedy of the horizon–climate change and financial stability. Speech Given Lloyd’s Lond. 2015, 29, 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Battiston, S.; Dafermos, Y.; Monasterolo, I. Climate risks and financial stability. J. Financ. Stab. 2021, 54, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGFS, A. A Call for Action: Climate Change as a Source of Financial Risk; Network for Greening the Financial System: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Monasterolo, I. Climate change and the financial system. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Energy finance: Background, concept, and recent developments. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.H.; Chew, B.C.; Hamid, S.R. A holistic perspective on sustainable banking operating system drivers: A case study of Maybank group. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2017, 9, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidjaya, P.G.; Widagdo, A.K. Sustainability reporting in Indonesian listed banks: Do corporate governance, ownership structure and digital banking matter? J. Appl. Account. Res. 2019, 21, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.Z.; Bose, S.; Johns, R. Regulatory influences on CSR practices within banks in an emerging economy: Do banks merely comply? Crit. Perspect. Account. 2020, 71, 102096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, B.; Lippai-Makra, E.; Szládek, D.; Kiss, G.D. The contribution of ESG information to the financial stability of European banks. Pénzügyi Szle./Public Financ. Q. 2021, 66, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, A.; Roberts, G.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1794–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, M.; Lodh, S. Do banks value the eco-friendliness of firms in their corporate lending decision? Some empirical evidence. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2012, 25, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.; Marimuthu, M.; bin Mohd, M.P.; Isa, M. The nexus of sustainability practices and financial performance: From the perspective of Islamic banking. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.; Marimuthu, M.; Hassan, R. Sustainable business practices and firm’s financial performance in Islamic banking: Under the moderating role of Islamic corporate governance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Zhu, Z.; Kirkulak-Uludag, B.; Zhu, Y. The determinants of green credit and its impact on the performance of Chinese banks. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Chowdury, R.K. Corporate Sustainability in Bangladeshi Banks: Proactive or Reactive Ethical Behavior? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre Olmo, B.; Cantero Saiz, M.; Sanfilippo Azofra, S. Sustainable Banking, Market Power, and Efficiency: Effects on Banks’ Profitability and Risk. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, L.; Mastromatteo, G.; Molocchi, A. Extending ‘environment-risk weighted assets’: EU taxonomy and banking supervision. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 11, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, S.; Gimpel, H.; Sarikaya, S. Bank customers’ decision-making process in choosing between ethical and conventional banking: A survey-based examination. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 89, 655–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, S.; Mazzù, S.; Naciti, V.; Vermiglio, C. Sustainable development and financial institutions: Do banks’ environmental policies influence customer deposits? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibe-enwo, G.; Igbudu, N.; Garanti, Z.; Popoola, T. Assessing the relevance of green banking practice on bank loyalty: The mediating effect of green image and bank trust. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbudu, N.; Garanti, Z.; Popoola, T. Enhancing bank loyalty through sustainable banking practices: The mediating effect of corporate image. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Rabbani, M.R.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cheng, G.; Zia-Ud-Din, M.; Fu, Q. CSR, co-creation and green consumer loyalty: Are green banking initiatives important? A moderated mediation approach from an emerging economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburu, I.A.; Pescador, I.G. The effects of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: The mediating effect of reputation in cooperative banks versus commercial banks in the Basque country. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, D.; Atwal, G.; Chaudhuri, A.; Dave, K. Antecedents of Intention to Use Green Banking Services in India (No. hal-02007553). 2016. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/hal/journl/hal-02007553.html (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Taneja, S.; Ali, L. Determinants of customers’ intentions towards environmentally sustainable banking: Testing the structural model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterolo, I. Embedding finance in the macroeconomics of climate change: Research challenges and opportunities ahead. In CESifo Forum; ifo Institut-Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung an der Universität München: München, Germany, 2020; Volume 21, pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gunningham, N. Financing a low-carbon revolution. Bull. At. Sci. 2020, 76, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, R.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, D.; Xia, Y. Can green financial development promote renewable energy investment efficiency? A consideration of bank credit. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Xie, Q.; Shen, Z. Impact of green credit on high-efficiency utilization of energy in China considering environmental constraints. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh–Hesary, F.; Nakahigashi, M. Modelling the social funding and spill-over tax for addressing the green energy financing gap. Econ. Model. 2018, 77, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Sirichand, K.; Vivian, A.; Wang, X. How connected is the carbon market to energy and financial markets? A systematic analysis of spillovers and dynamics. Energy Econ. 2020, 90, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhgaliyeva, D.; Kapoor, A.; Liu, Y. Green bonds for financing renewable energy and energy efficiency in South-East Asia: A review of policies. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2019, 10, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyowati, A.B. Mitigating Energy Poverty: Mobilizing Climate Finance to Manage the Energy Trilemma in Indonesia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, M. The financing efficiency of listed energy conservation and environmental protection firms: Evidence and implications for green finance in China. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyowati, A.B. Mitigating inequality with emissions? Exploring energy justice and financing transitions to low carbon energy in Indonesia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 71, 101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourcet, C.; Bovari, E. Exploring citizens’ decision to crowdfund renewable energy projects: Quantitative evidence from France. Energy Econ. 2020, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hamawandy, N.M.; Wahid, F.; Rjoub, H.; Bao, Z. Renewable energy resources investment and green finance: Evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, R.; He, Z. The impact of environmental pollution and green finance on the high-quality development of energy based on spatial Dubin model. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Khan, H.Z.; Monem, R.M. Does green banking performance pay off? Evidence from a unique regulatory setting in Bangladesh. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2020, 29, 162–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.Z.; Bose, S.; Mollik, A.T.; Harun, H. “Green washing” or “authentic effort”? An empirical inves-tigation of the quality of sustainability reporting by banks. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2021, 34, 338–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, G.; Bos, J.W.; Kleimeier, S. Self-regulation in sustainable finance: The adoption of the Equator Principles. World Dev. 2019, 122, 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ullah, I.; Afridi, F.-E.; Ullah, Z.; Zeeshan, M.; Hussain, A.; Rahman, H.U. Adoption of green banking practices and environmental performance in Pakistan: A demonstration of structural equation modelling. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13200–13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.Z.; Bose, S.; Sheehy, B.; Quazi, A. Green banking disclosure, firm value and the moderating role of a contextual factor: Evidence from a distinctive regulatory setting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 3651–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.; Foxon, T.J. A socio-technical perspective on low carbon investment challenges–Insights for UK energy policy. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2015, 14, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurey, A.; Kandpal, T. Carbon abatement potential of solar home systems in India and their cost reduction due to carbon finance. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambe, F.; Jürisoo, M.; Lee, C.; Johnson, O. Can carbon finance transform household energy markets? A review of cookstove projects and programs in Kenya. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltais, A.; Nykvist, B. Understanding the role of green bonds in advancing sustainability. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhooda, S. Asia, the Multilateral Development Banks and Energy Governance. Glob. Policy 2011, 2, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Y. The Effect of Green Finance on Energy Sustainable Development: A Case Study in China. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2019, 57, 3435–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lian, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xia-Bauer, C. Unlocking green financing for building energy retrofit: A survey in the western China. Energy Strat. Rev. 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglietta, M.; Hourcade, J.-C.; Jaeger, C.; Fabert, B.P. Financing transition in an adverse context: Climate finance beyond carbon finance. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2015, 15, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, J.; Goutte, S.; Ji, Q.; Guesmi, K. Green finance and the restructuring of the oil-gas-coal business model under carbon asset stranding constraints. Energy Policy 2020, 149, 112055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, J. The green bond market: A potential source of climate finance for developing countries. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2018, 9, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikau, S.; Volz, U. Central bank mandates, sustainability objectives and the promotion of green finance. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 184, 107022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, M.M.; Gallagher, K.P.; Li, Z. Renewable Energy: The Trillion Dollar Opportunity for Chinese Overseas Investment. China World Econ. 2018, 26, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, A.; Rosmin, M.; Volz, U. The role of central banks in scaling up sustainable finance–what do monetary authorities in the Asia-Pacific region think? J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2020, 10, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncoroni, A.; Battiston, S.; Escobar-Farfán, L.O.; Martinez-Jaramillo, S. Climate risk and financial stability in the network of banks and investment funds. J. Financial Stab. 2021, 54, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenet, H.; Ryan-Collins, J.; van Lerven, F. Finance, climate-change and radical uncertainty: Towards a precautionary approach to financial policy. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterolo, I.; Zheng, J.I.; Battiston, S. Climate transition risk and development finance: A carbon risk assessment of China’s overseas energy portfolios. China World Econ. 2018, 26, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrocher, N.; Cappa, E. The Role of public interventions in inducing private climate finance: An empirical analysis of the solar energy sector. Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthäus, D.; Mehling, M. De-risking Renewable Energy Investments in Developing Countries: A Multilateral Guarantee Mechanism. Joule 2020, 4, 2627–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, F.; Klöck, C.; Dornan, M. Vulnerability, good governance, or donor interests? The allocation of aid for climate change adaptation. World Dev. 2018, 104, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzold, C.; Weiler, F. Allocation of aid for adaptation to climate change: Do vulnerable countries receive more support? Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2017, 17, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Huang, Y. Exploring the Schemes for Green Climate Fund Financing: International Lessons. World Dev. 2018, 101, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.T.; Weikmans, R. Postface: Fragmentation, failing trust and enduring tensions over what counts as climate finance. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2017, 17, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J.; Skovgaard, J.; Kim, S.; Roberts, J.T.; Rossati, D.; Stadelmann, M.; Reich, H. Acting on Climate Finance Pledges: Inter-Agency Dynamics and Relationships with Aid in Contributor States. World Dev. 2015, 68, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remling, E.; Persson, Å. Who is adaptation for? Vulnerability and adaptation benefits in proposals approved by the UNFCCC Adaptation Fund. Clim. Dev. 2014, 7, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelmann, M.; Roberts, J.T.; Michaelowa, A. New and additional to what? Assessing options for baselines to assess climate finance pledges. Clim. Dev. 2011, 3, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gampfer, R.; Bernauer, T.; Kachi, A. Obtaining public support for North-South climate funding: Evidence from conjoint experiments in donor countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomsrød, S.; Wei, T. Business as unusual: The implications of fossil divestment and green bonds for financial flows, economic growth and energy market. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, N. What is adaptation to climate change? Epistemic ambiguity in the climate finance system. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2017, 17, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ranka | Source | Documents | Citations | Aver Cit |

| 1 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | 113 | 1082 | 9.58 |

| 2 | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment | 51 | 453 | 8.88 |

| 3 | Energy Policy | 19 | 719 | 37.84 |

| 4 | Ecological Economics | 16 | 717 | 44.81 |

| 5 | Climate and Development | 15 | 190 | 12.67 |

| 6 | International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics | 15 | 257 | 17.13 |

| 7 | International Journal of Green Economics | 13 | 66 | 5.08 |

| 8 | World Development | 11 | 348 | 31.64 |

| 9 | Energy for Sustainable Development | 9 | 188 | 20.89 |

| 10 | Environmental Science and Pollution Research | 9 | 243 | 27.00 |

| Rankb | Sources | Documents | Citations | Aver Cit |

| 1 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | 113 | 1082 | 9.58 |

| 2 | Energy Policy | 19 | 719 | 37.84 |

| 3 | Ecological Economics | 16 | 717 | 44.81 |

| 4 | Finance Research Letters | 7 | 492 | 70.29 |

| 5 | Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment | 51 | 453 | 8.88 |

| 6 | World Development | 11 | 348 | 31.64 |

| 7 | Nature Climate Change | 6 | 310 | 51.67 |

| 8 | Global Environmental Change | 9 | 301 | 33.44 |

| 9 | International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics | 15 | 257 | 17.13 |

| 10 | Environmental Science and Pollution Research | 9 | 243 | 27.00 |

| Rankc | Sources | Documents | Citations | Aver Cit |

| 1 | Finance Research Letters | 7 | 492 | 70.29 |

| 2 | Nature Climate Change | 6 | 310 | 51.67 |

| 3 | Ecological Economics | 16 | 717 | 44.81 |

| 4 | Energy Policy | 19 | 719 | 37.84 |

| 5 | Global Environmental Change | 9 | 301 | 33.44 |

| 6 | Global Finance Journal | 5 | 162 | 32.40 |

| 7 | World Development | 11 | 348 | 31.64 |

| 8 | Environmental Science and Policy | 8 | 232 | 29.00 |

| 9 | Environmental Science and Pollution Research | 9 | 243 | 27.00 |

| 10 | Energy for Sustainable Development | 9 | 188 | 20.89 |

| Author (s) and Year | Title and Journal | Cit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Campiglio E. (2016) [5] | Beyond carbon pricing: The role of banking and monetary policy in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy”, Ecological Economics | 202 |

| 2 | Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino (2019) [40] | The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment, “Finance Research Letter” | 190 |

| 3 | Robiou Du Pont et al., (2017) [41] | Equitable mitigation to achieve the Paris Agreement goals, “Nature Climate Change” | 143 |

| 4 | Ziegler et al., (2012) [42] | Carbon outcomes of major land-cover transitions in SE Asia: Great uncertainties and REDD+ policy implications, “Global Change Biology | 141 |

| 5 | Zhang D et al., (2021) [43] | Public spending and green economic growth in BRI region: mediating role of green finance, “Energy Policy” | 140 |

| 6 | Zhang D et al., (2019) [17] | A bibliometric analysis on green finance: Current status, development, and future directions, Finance Research Letter | 125 |

| 7 | Capelle-Blancard and Monjon, (2014) [44] | The Performance of Socially Responsible Funds: Does the Screening Process Matter?”, European Financial Management” | 104 |

| 8 | Lewis J.I. (2010) [45] | The evolving role of carbon finance in promoting renewable energy development in China”, “Energy Policy” | 104 |

| 9 | Mohsin et al., (2021) [46] | Developing Low Carbon Finance Index: Evidence from Developed and Developing Economies, “Finance Research Letters” | 96 |

| 10 | Aizawa and Yang. (2010) [47] | Green credit, green stimulus, green revolution? China’s mobilization of banks for environmental cleanup, “Journal of Environment and Development”, | 91 |

| Cluster | Most Relevant Keywords | Occurrences | Relevance Score | Links | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adaptation Finance | 25 | 1.2041 | 17 | 142 |

| 1 | Carbon Finance | 74 | 1.0697 | 19 | 168 |

| 1 | Carbon Market | 45 | 1.8425 | 16 | 95 |

| 1 | Climate Change | 240 | 0.7599 | 52 | 855 |

| 1 | Climate Finance | 265 | 0.9649 | 37 | 673 |

| 1 | Climate Policy | 54 | 1.027 | 28 | 222 |

| 1 | Low Carbon Investment | 13 | 0.7498 | 12 | 37 |

| 1 | Market Failure | 11 | 0.8437 | 13 | 47 |

| 1 | Paris Agreement | 64 | 1.1244 | 26 | 326 |

| 1 | Renewable Energy | 35 | 0.5956 | 23 | 156 |

| 2 | Bank | 474 | 0.4842 | 58 | 1857 |

| 2 | Corporate Governance | 19 | 0.8771 | 11 | 37 |

| 2 | Driver | 35 | 0.4606 | 32 | 203 |

| 2 | Environmental Sustainability | 12 | 0.6101 | 21 | 81 |

| 2 | Ethical Bank | 14 | 0.8813 | 8 | 82 |

| 2 | Financial Inclusion | 16 | 0.821 | 15 | 39 |

| 2 | SDGs | 34 | 0.3067 | 22 | 119 |

| 2 | Social Impact | 18 | 1.088 | 9 | 35 |

| 2 | Stakeholder | 69 | 0.2868 | 41 | 334 |

| 2 | Sustainable Banking | 67 | 0.8563 | 20 | 330 |

| 3 | Attention | 56 | 0.1939 | 43 | 259 |

| 3 | Environmental Performance | 15 | 0.6392 | 16 | 87 |

| 3 | ESG | 34 | 0.7791 | 24 | 101 |

| 3 | Financial Performance | 43 | 0.5814 | 25 | 274 |

| 3 | Green bond | 97 | 1.3954 | 32 | 401 |

| 3 | Green Bond Market | 30 | 2.176 | 15 | 167 |

| 3 | Green Financing | 40 | 0.3639 | 22 | 277 |

| 3 | Sustainability Performance | 15 | 0.6915 | 15 | 155 |

| 3 | Sustainable Investment | 14 | 0.6033 | 17 | 79 |

| 4 | Green Credit | 31 | 2.6416 | 11 | 141 |

| 4 | Green Credit Policy | 11 | 1.6294 | 10 | 60 |

| 4 | Green Economy | 27 | 2.4084 | 15 | 124 |

| 4 | Green Finance | 261 | 0.8868 | 41 | 692 |

| 4 | Green Finance Policy | 15 | 1.5796 | 11 | 48 |

| 4 | Green Investment | 14 | 0.9176 | 20 | 57 |

| 5 | Bank Loyalty | 15 | 3.4198 | 5 | 114 |

| 5 | Green Banking | 73 | 0.888 | 22 | 462 |

| 5 | Green Banking Adoption | 15 | 1.3012 | 6 | 88 |

| 5 | Green Banking Practice | 42 | 1.5331 | 20 | 317 |

| 5 | Sustainable Banking Practice | 11 | 2.4922 | 8 | 107 |

| 6 | Climate Risk | 22 | 0.9197 | 19 | 73 |

| 6 | Central Bank | 18 | 0.4981 | 20 | 113 |

| 6 | Financial Stability | 17 | 0.766 | 17 | 67 |

| 6 | Regulator | 24 | 0.5108 | 30 | 150 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kashi, A.; Shah, M.E. Bibliometric Review on Sustainable Finance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097119

Kashi A, Shah ME. Bibliometric Review on Sustainable Finance. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097119

Chicago/Turabian StyleKashi, Aghilasse, and Mohamed Eskandar Shah. 2023. "Bibliometric Review on Sustainable Finance" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097119

APA StyleKashi, A., & Shah, M. E. (2023). Bibliometric Review on Sustainable Finance. Sustainability, 15(9), 7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097119