4.1. Local Legitimacy and Rootedness of the Oldambt Festivals

The investigated festivals have differing relationships with the local community due to their different backgrounds, visitor groups, and the amount of direct impact on local communities. A semi-professional organisation, mainly consisting of volunteers from the area, organises Festival Hongerige Wolf. According to its organisers, the festival relies on local community support and cooperation because it is organised in and around the settlement of Hongerige Wolf (R1, R2, R10). It can only be organised if this community generally supports the festival. Therefore, the festival organisers aim to maintain a good relationship with Hongerige Wolf citizens. For example, they organise discussion evenings in the village. The organisation tries to solve the issue if people disagree with festival elements. Some villagers nevertheless oppose the festival. They deliberately chose to live in the quiet and peripheral location of Hongerige Wolf and wanted to avoid a festival organised around their houses (R1, R2, R7, R10). Still, most Hongerige Wolf citizens are generally supportive and proud of their festival. One of the festival organisers explains this situation well:

“Every year, we do our utmost best with all residents. Some need more attention than others. We try to ensure that every concern gets attention. Some people are against the festival, even if it’s just a handful—less than 20%. Most local citizens support this festival.”

—R2.

For the other festivals, the organisational situation is more straightforward. Waterbei is organised in the town centre of Winschoten by local volunteers. Despite being busier during the festival than at other moments, this location is designed to host many visitors. A festival organiser, a local politician, a local entrepreneur, and local youth all explain that the entry-free festival attracts local citizens and people from elsewhere. Visitors are interested in this high-quality offer of street theatre (R6, R8, R14, R18, R19).

Grasnapolsky, organised in the former straw cardboard factory in Scheemda, is a relatively new festival. A professional organisation of rural newcomers organises the festival (R4, R5, R7). According to its organiser, a local entrepreneur and a civil servant, the festival involves local citizens, entrepreneurs, and institutions. For example, Grasnapolsky organises expeditions to local attractions for its visitors (R8, R12, R13, R14, R17). The festival has not yet encountered opposition from local citizens, who are optimistic about an event in De Toekomst (R4, R5, R17). Given its recent move towards Oldambt, local citizens only sometimes know Grasnapolsky. Likewise, the Oldambt area is new to most festival visitors, who mainly come from elsewhere (R4, R16, R18, R19) [

53].

The Groningen province organises Pura Vida in a unique location within the Blauwestad area. According to some respondents and media, the festival has helped to attract new residents to Blauwestad (R3, R7, R11, R17) [

54]. According to local youth, their generation is less interested in Pura Vida than older people (R3, R18, R19). In recent editions, there have been few complaints about the festival’s organisation. Local inhabitants explain that they like this event, which shows the beauty of the Blauwestad project (R8, R18, R19). A local entrepreneur, who does not economically benefit from the festival, describes the festival as follows:

“There are about 20,000 people. Many with boats on the water. It’s great…a goosebumps event. It is locally very positively regarded.”

—R14.

The festivals in Oldambt make use of local resources to a different extent. According to a local and provincial civil servant, all festivals use local political capital by finding governmental support and subsidies (R7, R13). Festival Hongerige Wolf also uses natural, economic, and human capital. A festival organiser and a local citizen explain that it celebrates the spacious and peripheral surroundings of the small village where it is organised and buys material from local companies (R7, R10). A local citizen explains how many of the inhabitants of Hongerige Wolf are involved in this:

“Our neighbour has a family campsite during the festival. Some people sell books and antiques from their sheds. Someone nearby serves pastries and local food on her terrace. Another person makes soup and jams and sells them to visitors. So local citizens participate.”

—R10.

Waterbei uses existing human, cultural and economic capital in Winschoten. It is organised by local citizens involved in the cultural sector and supported by local entrepreneurs (R6, R14). Grasnapolsky mainly embraces the built and cultural capital of Oldambt by using the former straw cardboard factory, De Toekomst. The organisers and owner of the location explain that this also enables Grasnapolsky to interest visitors in the unique social history of the area (R4, R5). Pura Vida is focused on the existing natural capital and is organised on Oldambt Lake in Blauwestad (R3, R17). When considering the organisational model of the festivals, it stands out that the community-led festivals of Hongerige Wolf and Waterbei use a more comprehensive set of local resources than the private-led Grasnapolsky and government-led Pura Vida festival.

The festivals in Oldambt benefit the area in multiple ways. There are clear cultural benefits. During all the events, local citizens are confronted with ideas, people, and art forms that they would probably only come across during these festivals. A broad range of respondents argues that the festivals create a cultural clash between local inhabitants, newcomers, and visitors. This can lead to new ideas that strengthen the cultural offer in this peripheral area (R2, R8, R11, R16). Local citizens also start to see their area differently, which helps to develop cultural benefits and a sense of pride (R9, R10, R18, R19). A former Alderman of the municipality puts this as follows:

“We need other people from outside who come here to make us realise Oldambt’s uniqueness because many local inhabitants no longer see it. That you can do something with it... For example, someone took the risk to buy De Toekomst, which many people just wanted to demolish. Now, it has been completely renovated and hosts Grasnapolsky… Even when organised by others, the cultural events in the area make local citizens realise how unique Oldambt is.”

—R8.

In other contexts, cultural festivals also tend to support the reinvention of rural areas [

3,

27]. Especially Grasnapolsky and Festival Hongerige Wolf have an essential role in reinventing the area. A festival organiser of Grasnapolsky explains that it explicitly seeks to make its visitors from outside Oldambt familiar with the unique history of the building and the area in which it is organised (R4). The founder of Festival Hongerige Wolf explains that it was founded to introduce visitors from urban areas to the attractiveness of the vast landscapes of Oldambt (R1, R10). Therefore, the festivals help both local citizens and visitors reinvent the area.

The festivals also have economic benefits. With its cultural festivals, many new visitors came to Oldambt. Grasnapolsky surveyed their visitors in 2019 and found that 42% had never visited the area before, and 74% wanted to know more about Oldambt after seeing the festival [

53]. According to local and regional politicians and festival organisers, visitors are able to see the area because of the diverse offer of cultural events. This has direct and potential future touristic benefits (R1, R4, R8, R12, R17). Dutch rural areas could benefit from small-scale tourism [

55]. Measuring the effects on the local economy is difficult, but the festivals attract more tourists to Oldambt.

Given that the festivals’ budgets are limited, potential extra jobs and income streams for local people are created indirectly and temporarily. In addition, local civil servants argue that the festivals may be helping to attract new, but not young, residents to the area (R7, R17). Respondents think differently about the number of young people interested in visiting the festivals, with young respondents being more enthusiastic (R8, R10, R18, R19). A young woman from Oldambt explains her enthusiasm for Festival Hongerige Wolf:

“I usually go there with friends. You come across everyone from the village and surroundings. Young and older people go. You do not know those alternative people who come there. However, these people are also really involved. Then, you have a whole group of partying people standing there. You have no idea who they are, but it is fun to meet these people.”

—R19.

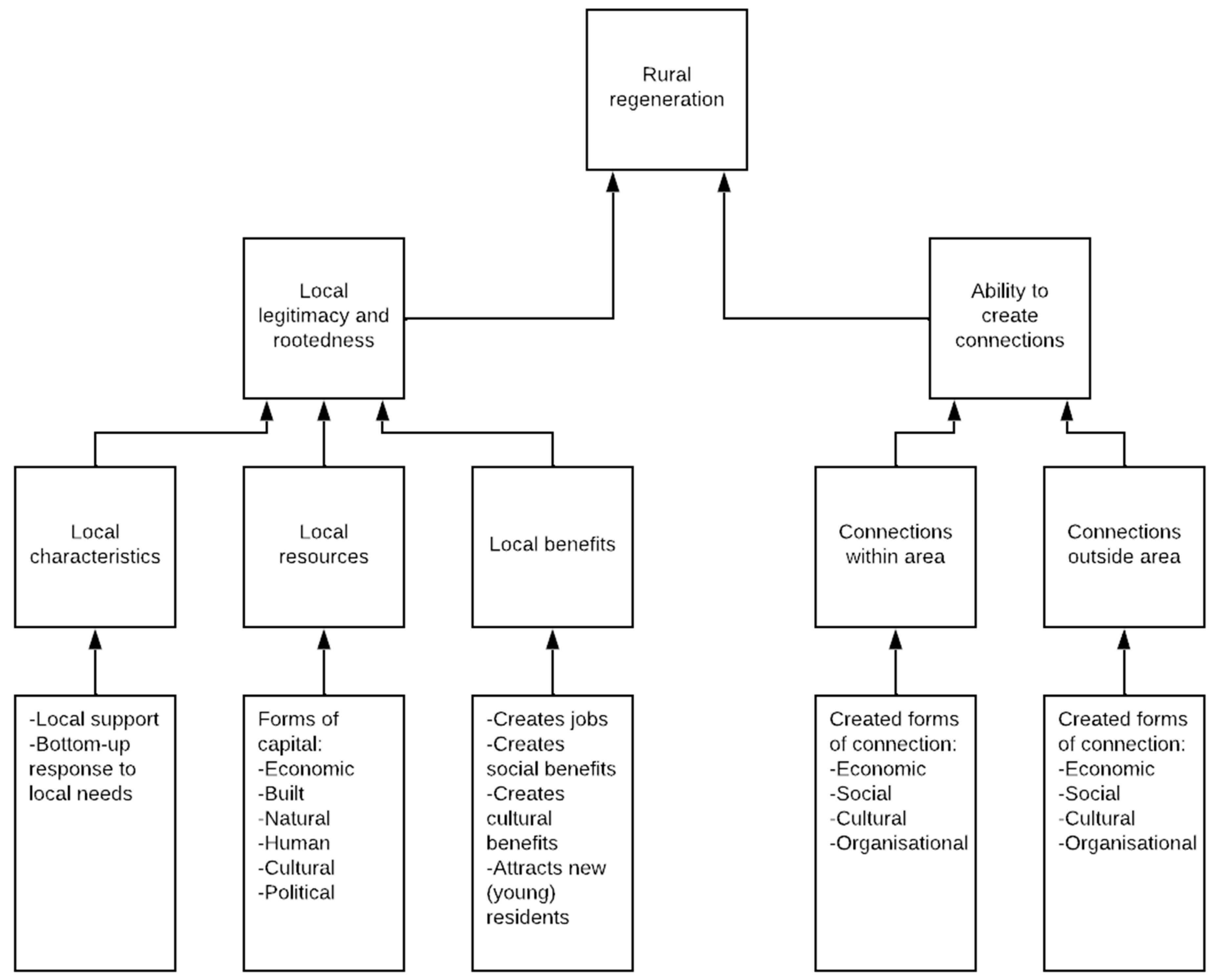

All investigated festivals have forms of local legitimacy and rootedness, but there are differences. Festival Hongerige Wolf’s location within a normally quiet village leads to some local critiques, whereas other festivals are more enthusiastically supported. The community-led festivals of Hongerige Wolf and Waterbei use local resources more than Grasnapolsky and Pura Vida. However, all festivals’ local benefits are considerable. Significantly, Grasnapolsky and Festival Hongerige Wolf contribute to the Oldambt area’s reinvention by seeking contact with local people and their stories and making them realise the area’s uniqueness. The increase in cultural festivals, also when led by newcomers, thus helps to strengthen Oldambt. Rural newcomers’ vital role confirms that they are essential in increasing cultural capital in rural areas [

18]. The local legitimacy of Grasnapolsky and its role in creating local benefits suggests that in the case of Oldambt, the theory-based expectation that community-led festivals use local resources and lead to more local benefits only holds for using local resources.

4.2. Interconnectedness Created by the Oldambt Festivals

The festivals in Oldambt help to establish networks within the area. This is, first and foremost, the result of local people who meet and develop social connections during the events (R6, R19). However, the festivals also strengthen organisational and cultural relationships within Oldambt. This opportunity is embraced through the Cultural platform of Oldambt, which seeks to unite all organisations and people in the Oldambt cultural sector and foster cooperation [

56]. Members throughout the cultural sector are part of the network, ranging from professional festival organisers to local amateur choirs and citizens operating within the industry. A local cultural entrepreneur and a local citizen describe the platform as a place where knowledge is shared between people from the cultural sector, leading to improvements in the cultural field of Oldambt. The cultural platform organises workshops, such as professionalising event organisation or applying for funding. Besides that, there are informal events where people can meet each other and create new ideas (R9, R10). Festival organisers and a local civil servant explain that the Oldambt municipality actively supports the Cultural platform (R2, R4, R7, R8).

By involving the festival organisers, the cultural sector in Oldambt can profit from their ideas and networks and, hence, become more robust. Some people and organisations actively embrace the Cultural platform to create economic, organisational, and cultural connections and improve their events and ideas. However, a festival organiser, civil servant and cultural entrepreneur mentioned that the platforms’ limited budgets and lack of active participation of some stakeholders make it harder for the Cultural platform to reach its goals. There is more potential to create stronger connections within the Oldambt cultural sector (R3, R7, R9). This is explained as follows:

“I have been running the Cultural platform for years, but do it for free, although it takes much time…The cultural sector could become more professional. However, it would be best to have leadership, investors, cultural entrepreneurship, and support…I once organised a series of workshops on writing a project plan. The first two meetings were well attended, with 25 visitors, and the third meeting had much fewer visitors. As a result, opportunities were missed to professionalise and learn from each other.”

—R9.

The festivals in Oldambt also help establish networks outside the Oldambt area. For example, Festival Hongerige Wolf creates social connections between local citizens and visitors from elsewhere. Next to discovering new music and art, visitors are also interested in meeting people with different backgrounds. Most visitors come from outside Oldambt, and local people who visit the festival are interested in meeting them and showing the beauty of their area (R2, R8, R10, R18, R19). The connection between local citizens, outside visitors and artists helps strengthen local citizens’ networks outside their area and may also support Oldambt.

The network effects may also be reached through the improved reputation of the area because of the cultural events in Oldambt. Most respondents agree that this reputation is improving quickly and that organising such diverse, high-quality cultural events contributes to that (R3, R7, R10, R13). The festivals may make Oldambt citizens prouder and increase their willingness to be an ambassador of their area. A provincial civil servant who also has a role in organising Pura Vida has the following explanation:

“You attract a category of people who would otherwise not come here. That has an impact on local citizens. The attitude here was always: ‘it was nothing, is nothing, and will be nothing.’ We have not been proud enough of the area. However, recently, this is changing. Local citizens see that more is possible. After years of negativity, there is now more positivity. People are proud of their area because they see that something is happening. More events, more tourists coming to our area, more people coming to buy a house. This makes local citizens prouder.”

—R11.

Furthermore, local entrepreneurs maintain that when people in other parts of the country learn about the diverse offer of cultural festivals, they may be positively surprised and alter their view of the area (R5, R9, R17). Hence, the more active ambassadorship will be recognised by people who now know about the assets of Oldambt.

In contrast to earlier periods, being from Oldambt may open doors instead of closing them, attracting more rural newcomers, businesses, and jobs. Even if the effect of these organisational and economic connections is limited, it would still be precious for an area that has encountered high unemployment rates and periods of depopulation over recent decades (R12, R14, R16). As was expected based on the literature, the cultural festivals in Oldambt thus enable more interconnectedness, both in and outside the area. This strengthens the reinvention of Oldambt.

Table 3 summarises the rural regeneration created through the Oldambt festivals.