1. Introduction

An ethnic group is defined by race, religion, national origin, or a combination of these factors contributing to unity and identity [

1]. The group may work together as a social unit because of a shared understanding of peoplehood or because other groups see them as separate entities [

2,

3]. Barth described an ethnic group as a group that meets the four criteria: it is biologically reproducing, shares core cultural values, creates a space for social contact and communication, and is characterized by its definitions and those of others [

4]. It does not, however, relate to the sense of belonging produced by a common socio-economic circumstance [

5]. The American sociologist David Riesman is credited with introducing the term “ethnicity” in 1953.

The ethnic group in the city may be the result of internal migration [

6]. However, to survive, the minority sects had to organize themselves and demand their rights. The most minor and dispersed groups left the countryside and moved to the cities for a more robust economic position. Bigger and geographically more united groups gathered in easily defensible places [

7].

People had to adapt to unfamiliar surroundings with kinship concepts but without kin. As a result, people who immigrated to cities formed relationships with others who spoke their language or were from the same region, creating relationships they could rely on just like they depended on kinship relationships back home [

8,

9]. At the same time, the ethnic group was included in the semantic range of kinship terms like brother, sister, and parent. Likely, some loyalty people felt toward their parents and siblings was also transmitted to the ethnic group [

9].

It is evident that when conflict and ethnic consciousness grow, group boundaries become more visible. As a result, signals that indicate participation in a particular group become more significant [

9,

10]. Conflict makes people feel threatened, leading to physical violence or assimilation, which can lead to losing one’s cultural identity [

6]. A strong need for uniformity arises to protect the group’s heritage, and the aggregation is perceived as continually being defensive [

3]. Cities such as Jerusalem, Belfast, Johannesburg, New Delhi, Beirut, Hong Kong, and Brussels are all experiencing severe intergroup conflict. Sometimes, unresolved nationalistic ethnic conflict centers on cities [

11]. These cities can serve as a battlefield for disputes between ethnic groups who claim these cities as their own [

12].

Ethnic groups question the legitimacy of a city’s political composition by calling for an equal degree of power [

11]. Such a flashpoint city may provide a significant and distinct barrier to the success of the wider regional and national peace process [

11]. Ethnicity is often exploited for political and financial purposes [

13]. Moreover, ethnic groups fight with each other over the distribution of public resources [

14]. All these reasons can increase the intensity of the conflict among the ethnicity in urban areas and extend to the whole country.

Ethnic segmentation appears to be influenced by prejudice, discrimination, disadvantage, and preferences [

15,

16]. Minorities are generally marginalized in overly segmented cities, linked with issues with safety, health care, employment, education, and poverty. Segregation of minorities is, therefore, often considered undesirable [

17,

18]. The majority group’s prejudice and discrimination limit the options available to members of minority groups. Even though most nations prohibit discrimination in the housing and employment sectors, and despite the rise in acceptance of minorities, discrimination happens every day [

19,

20]. Segregated communities based on race and religion are common targets for terrorist attacks in nations where terrorism is a problem. For instance, terrorist organizations have targeted the Shia minority in Afghanistan’s Kabul city, District 13.

After the 1950s, in the United States, where the most important and influential studies on urban segregation were produced [

21]. However, segregation dates to the history of urbanization [

22]. Unfortunately, there is insufficient research on urban segregation in Kabul city, and the study has not gained much popularity. Afghanistan’s researcher has generally studied the anthropology and background of ethnicity in the country. However, urban segmentation and how the government needs to address it have received less attention. Past studies examined the ethnic conflict during the civil war from 1992 to 1996, but not enough study has been done on Kabul’s urban segmentation after the civil war. Moreover, Sarwari et al. discovered that ethnicity had not been a focus in Kabul’s urban planning history [

23].

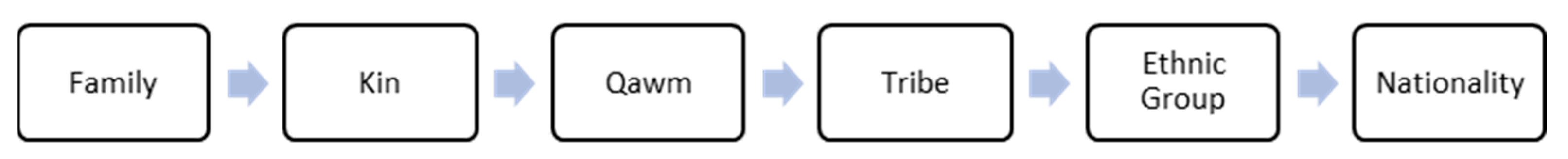

The migration facilitates intimate interactions among ethnic groups in Kabul city, according to research by Christine Issa: their most robust connections are built through relationships with their families, ethnic groups, and localities. See

Figure 1. Immigrants frequently integrate into the city’s established kin-based networks. Here, people can communicate with other group members to promote mutual understanding. They form relatively small groups because they need social assistance and cooperative systems for self-identification. They, therefore, live in a particular Kabul neighborhood [

24].

In Afghanistan’s anthropological and historical research, different term has been used to describe ethnic segmentation, i.e., ethnic group, tribe, and qawm. Although “tribe” is widely used nowadays, it might be confusing to refer to a group of people living a traditional lifestyle. It is related to the historical perceptions of white colonialists as uncivilized or primitive peoples residing in far-off, undeveloped areas [

25,

26]. Qawm is a fluid term used loosely for a smaller or more extensive group of people. For this reason, it is often preferred to use different terminologies, such as community or people. Hence, in our research, we will use the term community for the people living together in a group in Kabul city.

Researchers have differentiated two important use of the term community. The first is the neighborhood, town, and city-based territorial and geographic concepts of community. The second is relational and is concerned with the nature of interpersonal interactions without consideration of place. However, other studies contend that modern society forms communities more around interests and skills than place [

27,

28].

In our research, “community” has two distinct meanings: ethnic and geographical. Afghanistan ethnic communities of Pashtun, Tajik, and Hazara have relational communities based on their ethnicities. However, there are subdivisions of ethnic groups in Kabul city. They are divided into geographical communities. It is referred to those groups of people that share a specific geographical location in the rural part of the country. They share the same rural district or a combination of a few districts. They are mainly of the same ethnicity, but in some cases, they are a combination of several ethnicities. An example of these small geographical communities is Jaghori district residents of Ghazni province and Behsud district residents of Maidan-Wardak province in D13 of Kabul city, a sub-division of the Hazara ethnic relational community.

This article aims to illustrate several points of view on the complexity of ethnic division in cities affected by conflict, using Kabul as an example. Why has ethnic division become so permanent in Afghanistan’s urban areas? Why are people primarily loyal to their ethnic communities rather than the whole Afghanistan nationality? Does religion play a role in urban ethnic segmentation, or are people ethnically divided?

To find the sub-ethnic division, we addressed two main questions through our survey: Firstly, we validate the existence of geographical and territorial communities and what facilities these communities share. Secondly, why do sub-ethnic communities live together?

Finally, what should Afghanistan government policymakers and urban planners do about these communities? Moreover, we need the scientific world to know about the polarization of urban areas in Afghanistan. This study can be valuable in bringing to light the Afghanistan kinship and ethnic community traditions and a hierarchical loyalty culture. However, when seen positively, these communities can assist with safe and inclusive settlements, which is target 11 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations. They can also assist the government in establishing strong social communities for future sustainable cities.

2. Afghanistan Ethnicities Division

Afghanistan is a multi-ethnic country. It is due to its location at the edges of the powerful empires of history [

29]. People are primarily loyal to their relatives, community, tribe, and ethnic group, generally called

Qawm [

30]. To comprehend the segmentation in Afghanistan, we must distinguish between three degrees of communal identity: qawm, tribe, and ethnic group [

31]. Firstly, Qawm is an Arabic word that means solidarity groups. Afghans do not use the word “qawm” in a precise sense; instead, it can refer to any identifying group, including extended families, tribes, and even ethnic groups [

31].

Secondly, to preserve group identity and, more significantly, group rights and privileges one needs to belong to a tribe [

32,

33]. A kinship- and place-based system of identification and solidarity draws on tribal institutions, beliefs, customs, and common law [

31,

33]. Anthropologists have mostly abandoned the word tribe or have seldom used it to distinguish the specific social organization and political formations and solely to refer to a portion of the country’s social structure. Western anthropologists frequently use it to indicate archaic hordes of people who oppose a centralized state [

25]. This tribal structure is more prevalent among Pashtuns throughout southern and eastern Afghanistan [

31]. Thirdly, the ethnic groups believed they share the same genetics or common ancestors, history, and traditions.

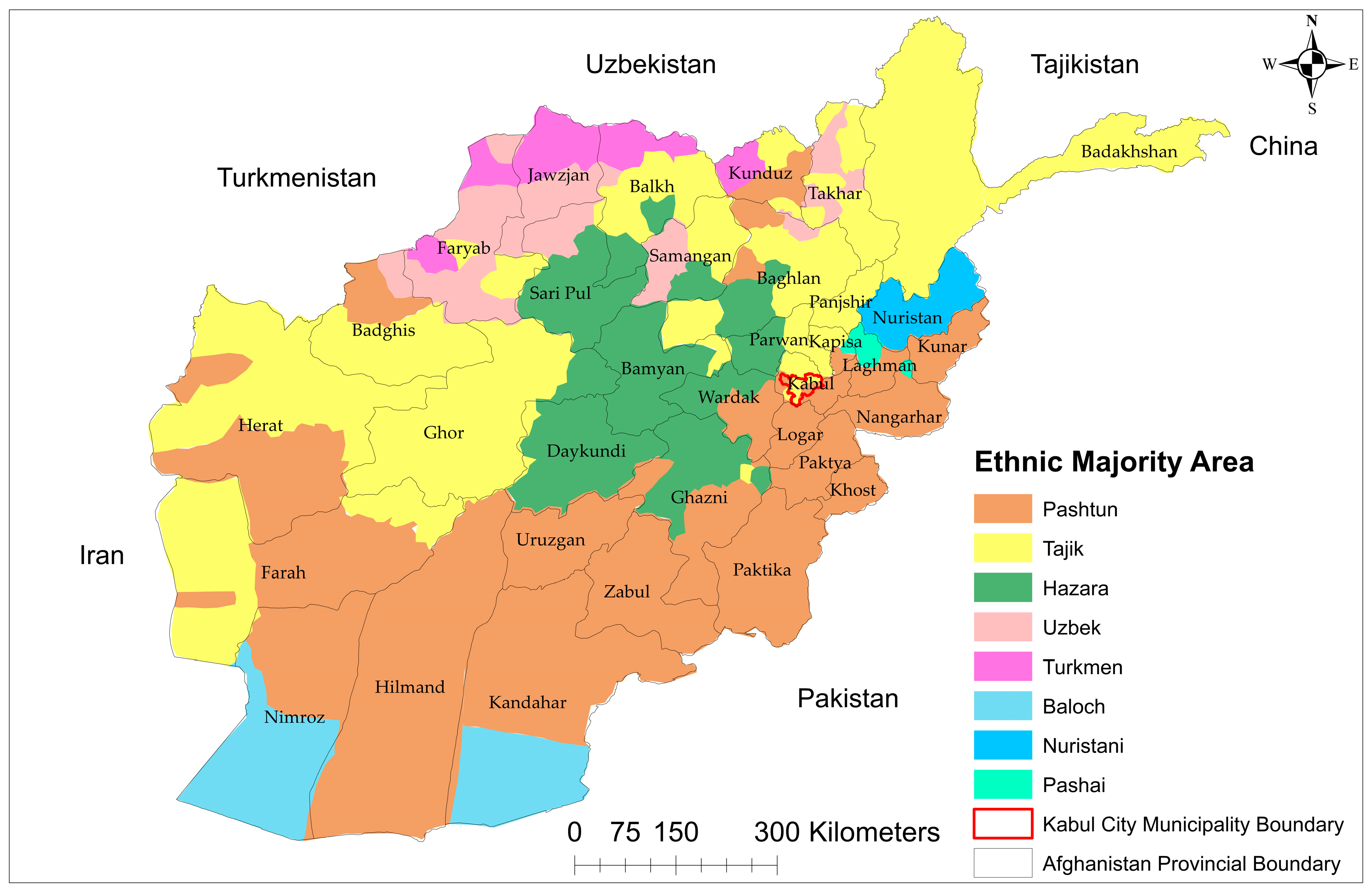

Ninety percent of Afghanistan citizens belong to one of four major ethnic groups [

34]: Pashtun, Tajik, Hazara, and Uzbek. Furthermore, the remaining ethnicities include Turkman, Baloch, Nuristani, Pashai, and others [

35]. Qawm, or ethnicity, is a fluid concept, making it nearly impossible and enormously challenging to estimate the size of an ethnic community [

33]. Afghanistan is administratively divided into 34 provinces and 374 districts [

36]. The ethnicities are settled all over the country. However, Pashtun ethnic groups are primarily settled in the southern provinces, Tajiks in the northeastern and western provinces, Hazaras in central, Uzbek, and Turkmen in northern Afghanistan [

37]. See

Figure 2. Nearly all Afghans (99%) are Muslims, the majority of whom are Sunnis of the Arian race (75–80%); the Hazaras are Shiite Muslims of Turko-Mongol heritage (with certain minorities being Sunnis and Ismailis) [

37,

38]. The Islamic religion was born in Saudi Arabia, and with the spread of Islam to the rest of the world, many people became Muslims. In other words, Muslims follow Islam regardless of the country in which they were born.

Afghanistan’s predominately rural society is becoming more urbanized due to internal migration to the major cities [

31]. The leading cause of the division at the national level is ethnic fragmentation, but qawm segmentation is common at the local level or among the political parties [

31]. The ethnic division will challenge urban planners and government policymakers to achieve inclusive and sustainable cities. More research has been done on Afghanistan’s ethnic division at the national level, but little research has focused on ethnic division in urban areas and how the country’s big cities are divided based on ethnicities and sub-ethnicities. This research will help to initiate a new line of research on urban segmentation and urban politics in Afghanistan.

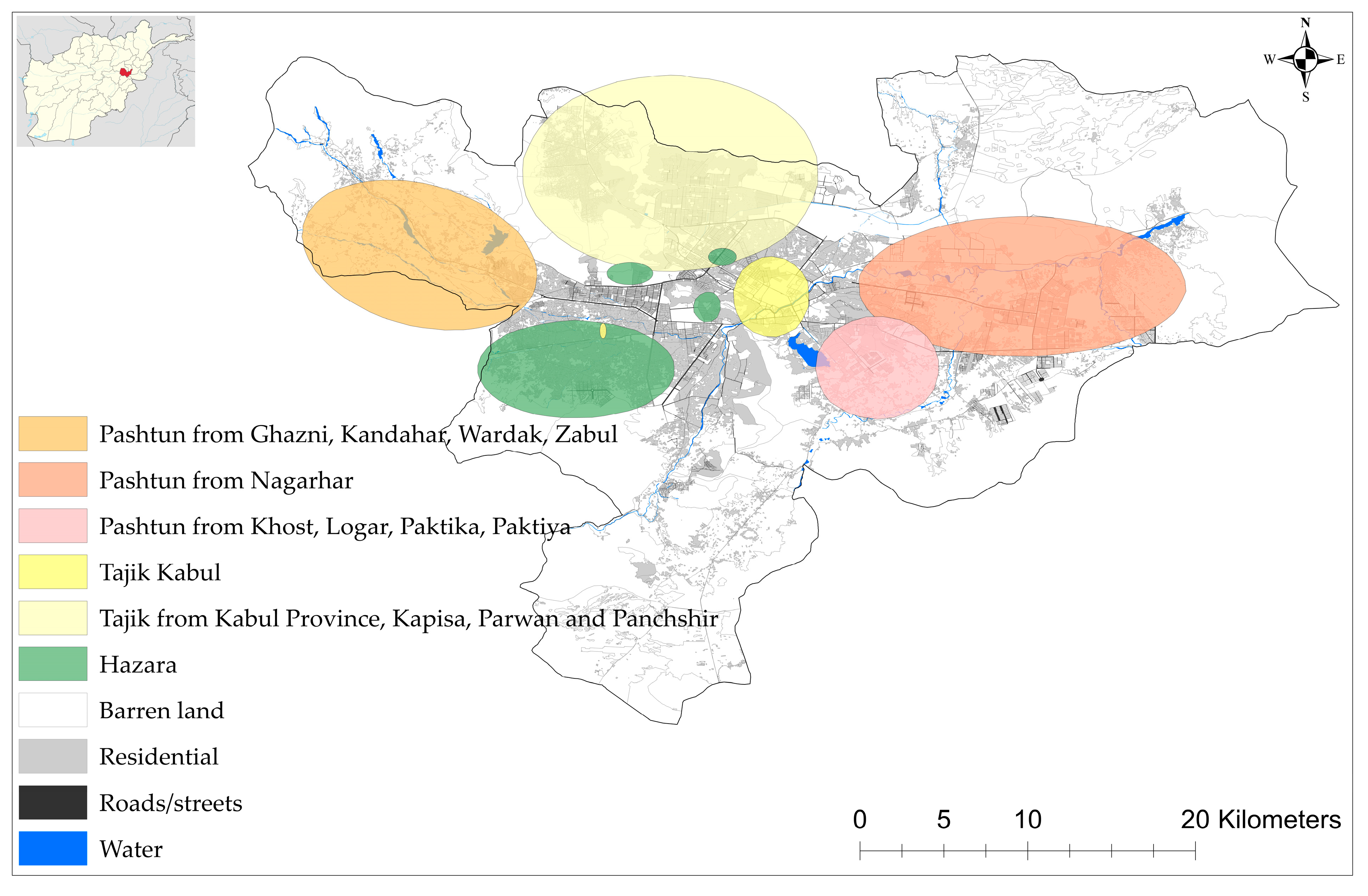

Kabul is the capital of Afghanistan, and Kabul city is the country’s largest city. The city’s population is estimated at 4 million, and 80 percent lives in unplanned areas [

36]. Kabul city has an ethnic urban landscape. District 13 (hereafter D13) is connected to the Maidan Wardak, Bamiyan, and central provinces of Hazarajat, which is why the Hazara people have settled on the west side of Kabul [

39]. Tajik to the north of Kabul due to its proximity to Parwan and other Tajik majority provinces; Pashtun to the south and east of Kabul due to its proximity to the Pashtun settlement provinces [

24]. See

Figure 3, which show the proximity of each ethnic region to their settlements in Kabul. A highway connects ethnic settlements to their region.

During the Civil War of 1992–1995, Kabul was divided among ethnic warlords, and each ethnic group chose a strategic location as its center to fight for control over Kabul [

37,

40,

41]. The civil war further polarized the city. In the following years, people migrating from rural areas and refugees returning to the country preferred settling among their ethnic communities. However, these ethnic groups are subdivided by their rural geographical location. The urban community of Kabul, which saw significant changes in the wake of the civil war, Is a unique case study due to the complexity of this ethnic division.

3. District 13 Kabul City

Kabul city is divided into 22

Nahia (districts). These districts are responsible for many duties, including providing building permits, collecting Safayi (sanitation) fees, and supporting local population databases [

36]. D13 has 96 Gozar (Sub-district) [

42]. Gozar is a traditional district unit built around one or more carefully located mosques with a common layout in neighboring Islamic nations [

43]. A Gozar is represented by the Wakil (community head), chosen by the locals, vetted by the police, and supported by the local government in Kabul. Recently, the Gozar unit was defined to refer to 500 or more dwellings [

44]. Almost all the D13 Residents live in the unplanned area, and the case study is also an unplanned area comprised of parts of Gozar 10 and 11.

D13 in western Kabul city is near the Hazara settlement region in the country [

39]. Hazara people settled in western Kabul long ago. During the civil war and the division of Kabul among ethnic Mujahidin, the Hazara fighters controlled western Kabul [

39]. Over the years, the lands were sold to newcomers and refugees who had returned to the country. Hence, today the majority of the residents in the district are Hazara [

44].

The bulk of D13 residents practices a Shiite branch of Islam. Shiite and Sunni are two major branches of Islam Religions that pray differently [

45]. They practice prayer in two different types of mosques. One of the other reasons that Hazara ethnicity is gathered in a community is that they are mostly Shia Muslims and share the same faith, which means they have a standard Mosque. However, generally, Shia and Sunni segregated settlements exist in Islamic countries.

The Hazara ethnic community of D13 preferred to settle in a small community of their rural district residents. In a way, they transformed their rural community into an urban community. Hazara districts closer to Kabul migrated first, like Behsud of Maidan Wardak. Therefore, most Behsud residents live near the main roads; as the Hazara settlements increased in western Kabul, the Hazara people of other parts of Afghanistan migrated to Kabul and settled in D13. When settling in D13, they lived among their relatives first or at least closer to their geographical communities’ members. Hence D13 is subdivided from Hazara ethnic communities into geographical communities. We chose our case study area in D13 because of the presence of visible geographical communities in the area.

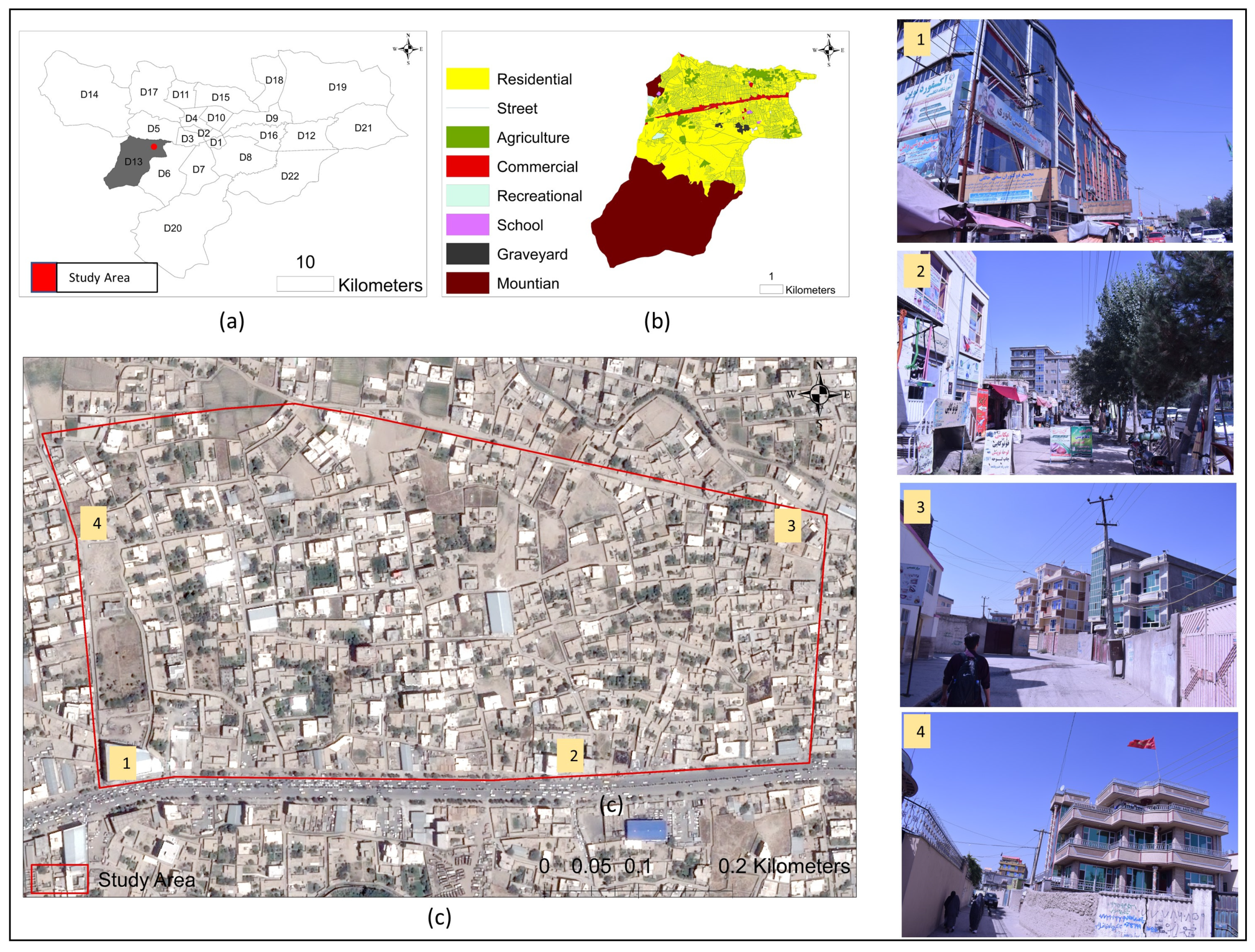

The case study site is connected to the main road, shown in

Figure 4. It is 28 hectares with an estimated population of around 5000 people in 600 houses. The area was chosen for two reasons. First, the site has diverse geographical communities. There are streets in the area, unofficially called based on the names of the rural district that people migrated from, like Jaghorian Street- Jaghori is a district in Ghazni province. The term “Jaghorian” translates into residents of Jaghori. However, this pattern of naming the area with the rural district is typical around D13. Secondly, the reason for choosing this area size is that it is one block of the new Kabul Urban Design Framework (KUDF) or Kabul’s new master plan. The road will be widened to connect informal settlements with the rest of the city. Destruction of the master plan will relocate part of the community, and we need to validate the community’s existence and prepare a resettlement plan. From the first master plan of Kabul city in 1978 to the 2013 master plan, and finally, Kabul urban design framework in 2018, they tried to include the public’s voice [

40,

46]. Unfortunately, implementing the master plan will still destroy many houses and communities in our study area [

47].

4. Materials and Methods

The study presented here used various methods to collect information about the types of ethnic segmentation. These included a literature review, a questionnaire to the residents, interviewing the Wakil Gozar (Head of the neighborhood), and interviews of residents face to face and over the phone.

To determine how Kabul is ethnically divided into various zones, we reviewed the literature on the history of Kabul’s urban community development and the ethnicities of Afghanistan over history and found the central location for each ethnic group. After careful analysis of the research, we drew a buffer zone around the center location of each ethnic settlement in the city to get a picture of where each ethnic community is located. General cultural, anthropological, and social theories were used to study the ethnicities and sub-ethnicities, which were then examined in the context of Afghanistan. We reviewed the research on Afghanistan qawm or solidarity groups to find why Afghanistan people preferred to live among their own family, kinship, tribe, and ethnicity. We wanted to know the relationship between qawm and Kabul city’s ethnic communities.

We gathered information from various Afghanistan organizations, including the Kabul Municipality District 13 Land-Use, UN-Habitat Land-Use for Kabul City, Satellite images, the new master plan created by Sasaki Company, and the Ministry of Urban Development and Land of Afghanistan. Combining the data from the literature review and survey, using the geographic information system (GIS), we developed maps of the study area and ethnic maps of Kabul City and Afghanistan.

A semi-structured interview was conducted in 144 houses at the end of 2019. The study area is along Shaheed Mazari Road, the main street of D13, at 800 m. The security situation in Kabul city was terrible, and it was tough to conduct the interview, as it was unsafe for surveyors. The houses near the three streets are interviewed; the first is Ghorjistan street, also called Behsud street. Behsud is one of the districts of Maidan Wardak province. The second street is Jaghorian street. Both Jaghori and Behsud districts are majority ethnically Hazara. The third street was Honchi Baghbanan, a Kabul old area name, and the residents are of Tajik ethnicity. We did observational research to find the current facilities that the community shares. We also interviewed the Wakil Gozar for the details of the communities.

We tried to minimize the bias in our research. However, almost 100 percent of the survey respondents are men; it is hard to interview women in Afghanistan’s patriarchal and religious society. If one knocks on a door for an interview, it will be directed to the family’s elders, primarily men. We ensured that the houses at every corner of each street were surveyed. However, most of the houses were detached, as it is easy to approach and survey, and it is believed that people living in detached houses are more long-term residents of the area. As the security of Kabul city was terrible, we tried to survey the houses near the streets, as it is considered comparatively safe to interview door to door. All the interview was done based on the resident’s willingness and consent in the area. People helped conduct the questionnaire. We used the questionnaire format from the ministry of urban development and land Afghanistan, and the ministry helped us with contacting the local leaders and organizations to conduct the interview smoothly.

The length of residence in the area differed for each household. Some households claimed they have lived for generations, and others migrated in the last 20 years. The questionnaire was designed to draw out information on the rural districts of the migrated residents. We also wanted to know, if the government makes land acquisitions for a public project, where do the residents want to be relocated? What are the reasons if the answer is their current location or in-situ resettlement? The KJ-Method was applied to analyze the responses for reasons. Japanese ethnologist Jiro Kawakita developed an idea-generating and prioritization method known as the KJ-Method or K.J. Technique. It is employed for brainstorming ideas for design, team, and project meetings [

48]. The method was applied by writing down the rough ideas and organizing them into main groups and subgroups based on their concept.

5. Results

The prime reason for people segmentation has been ethnicity, and religion comes second. People preferred to live where their family and kinship lived because of the traditional loyalty hierarchal structure. Hence, religion is not the prime factor in people’s decision-making about where to live. For example, D13 and western Kabul city have been a majority Shia faith of Hazara settlement; however, Sunni Hazara also lives in west Kabul. Tajik and Pashtun are both Sunni but live in different parts of Kabul.

There are visible minorities of different groups in every district in Kabul city, even though each of the more prominent ethnic communities tends to be concentrated in a particular area, specific urban neighborhoods have mixed populations. However, each ethnic group has rich and poor people living in the same neighborhood.

Ethnicity plays a minor role in many everyday transactions. People do their business deals based on closeness, effectiveness, and convenience rather than those belonging to their ethnic group. The majority of service providers prioritize profit and consistency in transactions. However, ethnic identity has an immediate, crucial significance in activities involving fundamental social institutions, like marriage or business connections. In the city of Kabul, ethnic identification may not matter much in casual interactions between people, but when conflict or the prospect of conflict arises, everyone becomes much more aware of their ethnicity and that of others.

Years of wars among the ethnicities, especially the bloody war of 1992 to 1996, created negative feelings between the groups. Civil war and mass killing history between ethnicities have polarized the city further. People talk about history in their everyday conversation and give examples of atrocities by other ethnicities towards their own. The wars between ethnic groups and religious differences have increased social distance.

Pashtun language is Pashto, and Tajik and Hazara speak Persian. Tajiks have copper-colored skin and round eyes, and Caucasian and Mediterranean features, such as Roman noses, have a similarly close look to Pashtun but in different languages. Hazaras have pointed cheekbones, Asian-like eyes, noses, and many more central Asian physical attributes. Uzbek and Turkman also have close similar looks to Hazara. The visible differences have exacerbated the social distances in urban areas. It also resulted in discrimination towards each other. Hence people preferred to live in segmented areas. It is more significant with minorities.

However, the architectural style of housing is the same throughout Kabul city. There is not any significant difference between ethnicities dwelling types. Three types of housing are common: old mud houses, the mix of mud and concrete houses, and new modern concrete houses. All these houses can be found in any neighborhood of ethnic informal settlements.

Sub-Ethnic Division

In terms of people living at the neighborhood level, they are divided into sub-ethnic communities. Western Kabul city is majority Hazara ethnic and Shia. However, the ethnic relational community in D13 is subdivided in to geographical communities. In Jaghorian street, we surveyed 40 houses; the result is shown in

Table 1. Of 40 houses, 24 are from the Jaghori district of Ghazni province, 15 are from old Kabul residents, and one is from Maidan Wardak province.

In Ghorjistan street, we surveyed 63 houses. Forty houses are from a single rural geographical area of Behsud district of Maidan-Wardak province; seven are from Ghorband valley of Parwan province; their ethnicity is Turkman. Ten houses are from the Jaghori district, five from Bamiyan Province, two from Kabul, and one from other parts of Ghazni province. See

Table 2.

Honchi Baghbanan street, an old community of Kabul residents, shows that most of these old Kabul residents live in their community, even after so many years of internal migration and diversification of Kabul city. We surveyed around 41 houses. We found that 26 of these houses are old Kabul residents, mostly Tajik, and nine are from Mazar Sharif province, belonging to Hazara ethnicity. Furthermore, the remaining four houses are from other parts of Ghazni province, and two are from Herat province. See

Table 3.

According to an interview with the Gozar head, each Gozar has 1500

Haveli (yard), and each

haveli has an average of three families or households. The area has three mosques, and around 130 Haveli share each community mosque. Based on Central Statistics Organization, 2010, the average number of people in a household in Afghanistan is around seven, and this estimation is still done to find an area’s population in Afghanistan. Two thousand eight hundred people share each community’s mosques. Hence, the average user of each community mosque can be half of the estimated population, as men only use mosques. See

Figure 5.

As shown in

Figure 5, the master plan passes through the existing community houses, and the main and collector roads will be widened to 80 m and 40 m, respectively. Hence, houses will be destroyed so many community households will be relocated.

We also wanted to find the community’s importance to the residents, we asked about the relocation after the urban renewal, or master plan was implemented. Fifty-two percent of the respondents, most landowners, want to live anywhere within District 13. Thirty-two percent prefer living in the same Gozar, with the existing neighbors and other amenities near the neighborhood. In comparison, 16 percent of respondents are willing to relocate anywhere in Kabul. The result shows that most people prefer relocating within the same district and neighborhood. See

Figure 6.

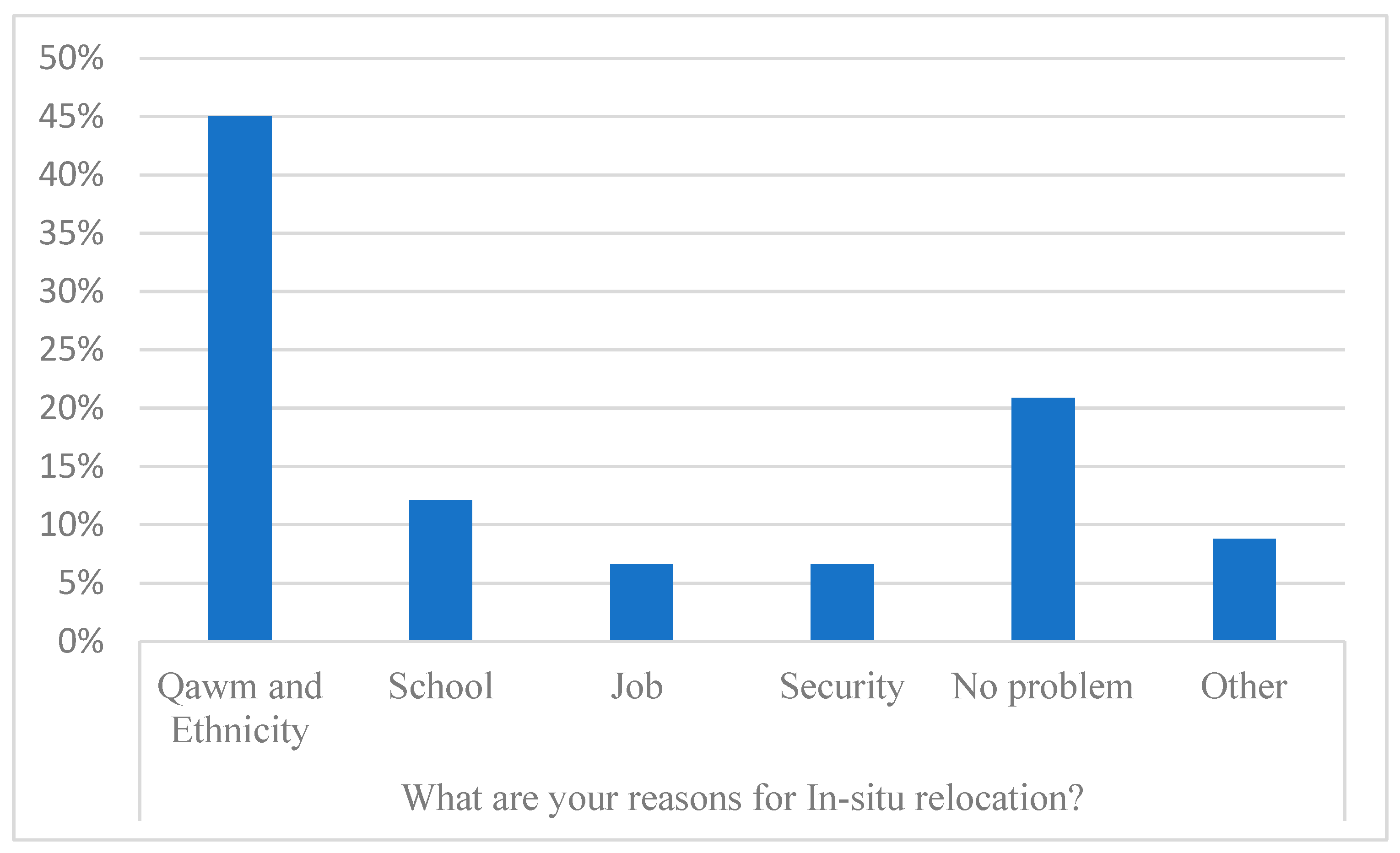

Residents were asked why they did not want to relocate outside the project area. Seventy-six landowners responded to our interview. It was an open-ended question. We used the K.J. method to categorize the rough answers into five main groups: ethnicity, close to their current school and university, security of the area, near their job, having no problem with relocation, and other reasons. Ethnicity comes up as the top reason for relocation. Qawm and Ethnicity is why people want to be relocated in situ or near their current location. See

Figure 7.

6. Discussion

Afghans are proud of their ancestors and their communities. The Long conflicts and civil wars have led to the city’s further polarization [

37]. The history of conflicts resulted in people living in a community they trust and communicate well. Our study has shown that ethnicity has played a crucial part in shaping the community development in Kabul city. Ethnicity is important when choosing where to live in the city. It is more significant than religion. In each ethnic settlement, minorities of other ethnicity exist. However, there are no conflicts in their daily businesses; people prefer profit and convenience in dealing with their routine transactions.

The geographical community division of D13 residents shows that Afghans are loyal to their grassroots identity groups, inspired by the old Afghanistan communal identity of qawm. Qawm is their exact word when responding to our interview on why they chose to live in this neighborhood. Qawm is a dominating feature of Afghan society [

49]. The qawm is a group of people with local or traditional interests who are united by kinship, tribal ties, or other links. It can also be a group united by shared sectarian, linguistic, or ethnic interests [

50]. At the local level, Afghanistan’s population is divided into various groups, so “qawm” is adaptable and expandable [

33]. It applies to these smaller groupings and principal ethnic groups and Afghanistan nation too [

33]. Most Afghans continue to be committed to their grassroots identification groups in addition to their ideologies and politics [

31]. The leading solidarity group in Afghanistan is the qawm, which is seen as the lowest common denominator of group loyalties rather than tribalism. Everyone is a member of a qawm, at least in the countryside [

31].

Before becoming an ethnic or tribal group, qawm was a solidarity group that guarded its members against the state’s intrusion and that of other qawm [

31]. Qawm can be why smaller geographical communities migrate from the same rural district and live together in Kabul city. If a rural resident says that a particular person is their qawm, they are either a close neighbor of their village or rural district or on a large scale of the same ethnicity. When people migrated to cities, they brought their qawm identity and preferred living together.

Knowing how the communities are developed in Afghanistan can help urban planners and policymakers in government to take the community seriously for decision-making on urban development, especially with crime rates skyrocketing in big cities of Afghanistan [

51]. Understanding how communities are established can help us design better homes that will be better maintained, allow for greater use of the surrounding spaces (streets and parks), and ensure protection from criminal activity [

52]. Additionally, residents invest the most in houses in areas with strong social networks [

53].

However, ethnic residential concentration will reduce solid social relationship formation [

54]. It will not be suitable for the future generation to have an inclusive and diverse neighborhood. Afghanistan has gone through a history of ethnic violence and racial cleansing [

33]; therefore, ethnic concentration will further divide people as us vs. them. Nevertheless, the geographical and ethnic community is part of the identity of a settlement in a specific area, such as D13 and other ethnic settlements of Kabul. The planners should be sensitive to the relocation and diversification of the existing ethnic communities. The city’s new public housing can be divided among each ethnicity for sustainable and diverse future communities. However, the new public housing should not be developed in an existing ethnic community settlement.

One promising model for an inclusive and diverse neighborhood is Singapore’s ethnic integration policy (EIP), which aims toward a race-neutral society of tomorrow. The state tightly regulates the housing market in Singapore. The EIP quota limits each block to a maximum of 87, 25, and 15% of families that are Chinese, Malay, or other Asian nationalities, respectively [

55]. Applying this model to Kabul city public housing, with a correct population and ethnic size numbers, can promote mixing and understanding across ethnic groups.

However, Singapore and Afghanistan’s economies and the rule of law differ significantly. Ethnic identity is a sensitive topic in Afghanistan, as per the history of violence towards each other. Residential enclaves had been forcibly removed and moved to new housing estates for all races in Singapore between the late 1960s and the early 1980s, which resulted in a rise in residential desegregation [

56]. The same way of relocation can not be implemented in Kabul city, removing the residents by force and replacing the ethnic settlements with new multi-ethnic residents. The majority of the Pashtun ethnicity controls the current government of Afghanistan; the relocation approach will be taken as ethnic cleansing and will increase ethnic violence in the future. Hence, the Afghanistan government should implement the EIP model in a new area, not an existing ethnic settlement.

6.1. Advantages of Geographical Communities

Afghans have lived in relational and geographical communities for a long time. They are even transforming their rural communities into urban communities. It must mean something; they feel connected and secure living with their qawm. Research has recommended that we purposefully base public policy on community values and human development and assess new policies because of the family community cohesiveness [

57,

58]. Qawm can bring a good sense of community to the residents in the urban area. This kinship and qawm identity living in Kabul are the reasons for the residents to build their infrastructure and facilities, such as mosques, build a safe community against crime, and can help with women’s freedom, especially in renting houses and joining ceremonies in the community.

The residents of the small geographical community know each other from the rural area or are relatives living together. They are the same qawm. Because the qawm is a solidarity group for Afghans, they trust each other more. It can help the women in the community to visit each other regularly, celebrate events and festivals, and even close women members of the qawm can live and rent houses there. With the new Taliban religious government in power, women’s rights have been restricted. Girls are not allowed to go to school or university. They are banned from public parks too. We need further research like this to understand Afghanistan’s traditional hierarchal culture, and it can help women’s rights within the community and help women at the neighborhood community level. Additionally, studies have indicated that social bonds strengthened by shared ethnic origin and a common culture improve children’s well-being [

59].

Qawm is the reason that rich and poor lives in the same community. The area has expensive concrete glasses-covered detached houses and poorly constructed mud houses in the same community. This type of composition exists in the same ethnic neighborhood informal settlement more than the diverse ethnic settlement in Kabul. People are more invested in their neighborhoods with the same ethnicity. The better economic composition of a community can help with individual income and the labor market in the area.

The neighborhood effect is a notion in economics and social science that holds that the composition of a neighborhood has an additional positive or negative impact on that people’s prospects or economic standing [

60,

61]. In order to offer diversity and enhance people’s lives, promote tolerance of social and cultural differences, increase the educational influence on children, and stimulate exposure to various lifestyles, class heterogeneity in neighborhoods has long been an objective of public policy.

Figure 8 shows pictures of the area where luxurious concrete detached houses and mud houses exist in the same neighborhood of the case study site.

Policies to implement the 2030 Agenda of Sustainable development goals (SDGs) of the United Nations (U.N.) address interlinkages within the social sector, as well as between the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development [

62]. Goal 11, make cities, and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable: addressed the needs for strong communities and civil societies in urban planning [

62]. By increasing the capacities of existing geographical communities, we can pursue sustainable livelihood opportunities. Because ethnicity, cultural diversity, and Community cohesion will be crucial for the sustainable cities of tomorrow.

Goal (11. a) of SDGs supports positive economic, social, and environmental links between urban, peri-urban, and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning [

62]. The ethnic community living in the city has migrated from rural areas of Afghanistan, and they own land and have close family members living in the rural village. Conserving these communities will help create a social link between rural and urban areas, which can help fulfill the SDGs in the long term.

Geographical Communities Share a Mosque

Each geographical community built a mosque where they prayed together. However, almost all mosques are for men only. The mosque is an essential facility in Islam, as Muslims visit it five times a day in the Sunni faith of Islam and three times in the Shia branch of Islam [

63]. The mosque is the center of Muslim religious, political, social, and educational activities under one roof [

64]. The community gathers around in the mosques for prayers, government, politics, wedding Nikah, funeral management, Ramadan, the celebration of Eid, and other special occasions [

65]. The community mosque also accommodates funeral ceremonies, and it is essential for the deceased’s family that the community they know is in large numbers at the funeral and the prayer. Moreover, a funeral ceremony is taken at the mosque for men, and people who know the family visit them for condolence. Nevertheless, the women meet the family at the deceased family’s home.

The mosque is also an educational center for some close communities, especially religious education. It is also a place where a member of the community volunteer to hold educational classes for the community kids, where they teach school subjects or prepare the students for exams like a university entrance exam. We can say that mosques have the characteristics of third-social spaces for the community other than the house and workplace of the residents; It is the prime location for each community to meet and have daily conversations to get support from community members [

66,

67]. However, the local community’s participation in mosques programs has reduced over the years [

68]. In other words, the mosques can be empty and disorderly, especially outside prayer times, and the visitors are mainly people of older ages [

66,

69].

There are two main types of mosques: firstly, the masjid Jami, which translates into “collective mosque,” a sizeable state-controlled mosque that is the center of more extensive community worship and the site of Friday prayer services, which is funded by big Islamic organization, government and some time the people. Secondly, the smaller mosques are operated privately by communities within the society [

63], which we will refer to as community mosques in this paper.

In the case study area, each geographical community has at least one local mosque where they gather for prayers, and there is one collective mosque.

Figure 9 shows four mosques in our study area.

Figure 9a shows Imam Askari Mosque with a plot area of 800 m

2. It is a Shia faith mosque, and the area is close to Ghorjistan street, where most Behsud district residents live.

Figure 9b shows the Jaghori community mosque of Fatimah-ul-Zahra, the area of the mosque is 600 m

2. Hazrat Bilal mosque, as shown in

Figure 9c, is the Honchi-Baghbanan community mosque. The residents practice the Sunni faith of Islam. Hence, they need their mosque in a majority Shia residency. The plot area of the mosque is 300 m

2.

The

Figure 9d shows a mosque at the street’s entrance, where most Jaghori district residents live at the end of the street. However, the mosque is a collective mosque, with an area of 700 m

2, which can be a mosque for a more extensive community of Shia faith in D13 and used as a religious education center.

The funding sources of these community mosques are the residents living in that community; they pay a certain amount monthly for the mosque maintenance and the salary of the Imam of the mosque. Sometimes, people also have donation boxes at the mosque where they donate money for community benefits. The community puts time and money into constructing the mosques, and they visit each other almost every day; hence relocating them will affect the sustainability of the community mosques.

7. Conclusions

Afghanistan is a diverse ethnic country spread across the provinces. The history of conflict and wars resulted in social isolation, and when they migrated to Kabul, they transferred their ethnic community to the city. Kabul is ethnically divided among different Pashtun, Tajik, and Hazara ethnicities. Generally, in Kabul city, a minority of a different ethnic group is present in every district, and most urban neighborhoods have mixed populations. Ethnicity has little influence on many everyday interactions. Each ethnic group does, however, have wealthy and impoverished people who commonly live close to one another.

There are mainly three reasons for ethnic segmentation in Kabul city. Firstly, and primarily is the customary lifestyle of hierarchal kinship values, in which people prefer to live among their relatives and ethnic groups. Secondly, the years of wars among ethnicity and discrimination have further increased the segmentation. Thirdly is the social support they get by living among their relatives and kinship. These three reasons have encouraged people to live among their ethnic group and be invested in their community.

Each ethnicity is subdivided into geographical communities. People live in these sub-ethnic communities because of Afghanistan’s old tradition of communal identity, known as qawm. Mosques are the only public facilities that each geographical community has. They pray together, have their community discussion in the mosque, and solve their community problem through their mosque. However, women in the community do not share any specific public facilities.

Ethnic and geographical communities are essential for Kabul residents. In the case of urban redevelopment, they want to be relocated in situ or near their current communities. Hence it is necessary to consider the importance of these communities to the residents while redeveloping any informal settlements in Kabul city. However, for relocation, ethnicity is more important for people than their geographical community. More people are willing to relocate outside their geographical communities if they are relocated to the same district of their ethnicity. It means that in choosing an area to live in Kabul or migrating to Kabul, ethnicity is a significant factor in choosing where to live.

Qawm can give a good sense of community to the people in Kabul city. The community of qawm trusts each other because of their loyalty hierarchal values; this will help them to invest more in their environment and infrastructure, such as building mosques. As Afghans trust their kinship more, this will help the women’s freedom in the community. Moreover, it will get the government closer to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals- by increasing the capacity of local communities to pursue sustainable livelihood opportunities.

Further research is needed on what brings this smaller community together, what support they get from it, what other facilities they share among different communities, and how these ethnic communities help women move freely in the community, join ceremonies, and help children’s well-being. We also need a plan for relocation in case of an urban redevelopment or other public projects to bring minimum destruction to the community.