Perspective on Two Major Pandemics: Syphilis and COVID-19, a Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Birth of Two Pandemics

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structure of the Article

2.2. Data Research Process

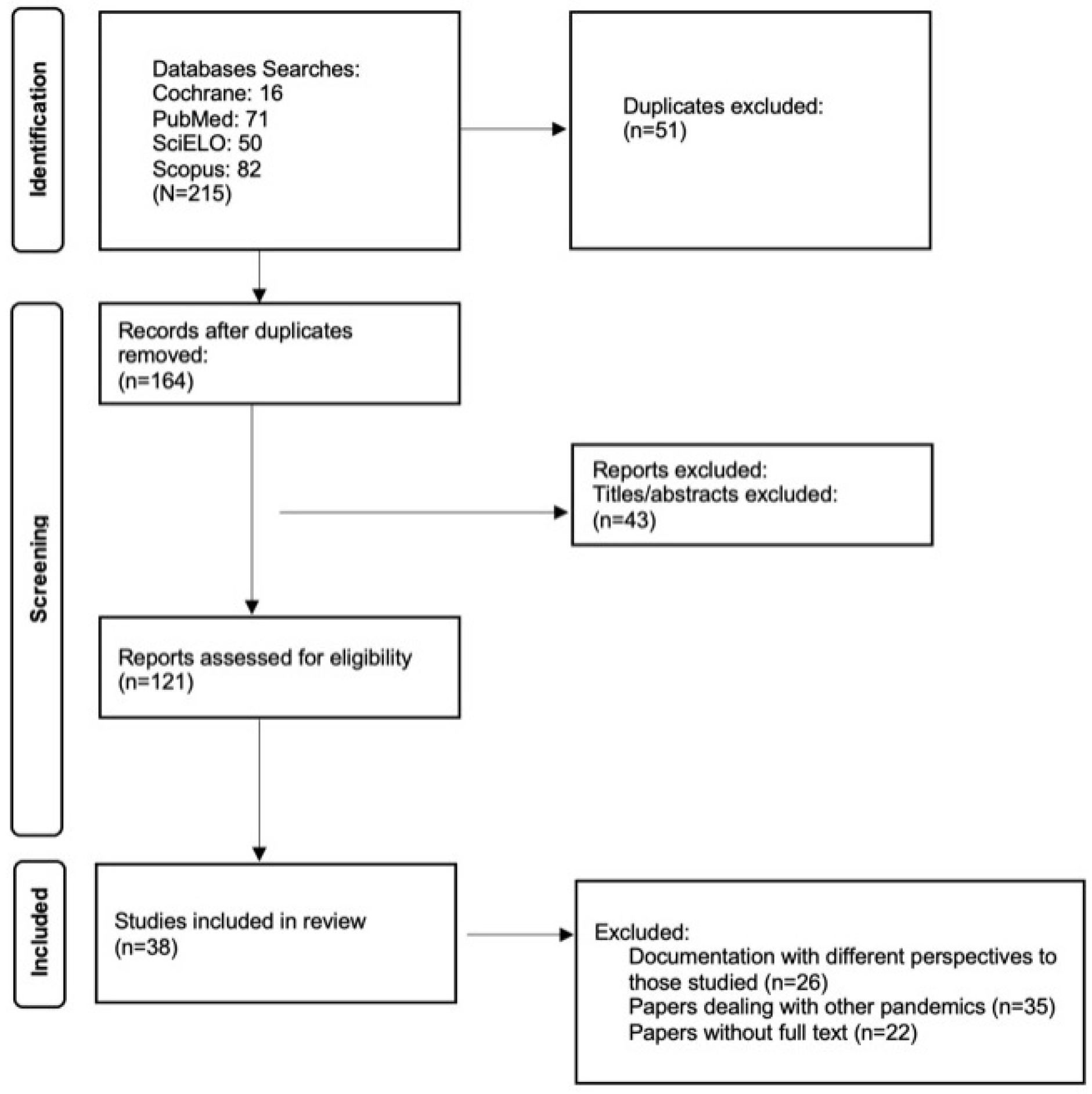

2.3. Information Review Process

2.4. Study of the Documents Used

2.5. Ethical Issues

3. Results

3.1. Health Professionals: On the Frontline of the Battle against Syphilis and COVID-19

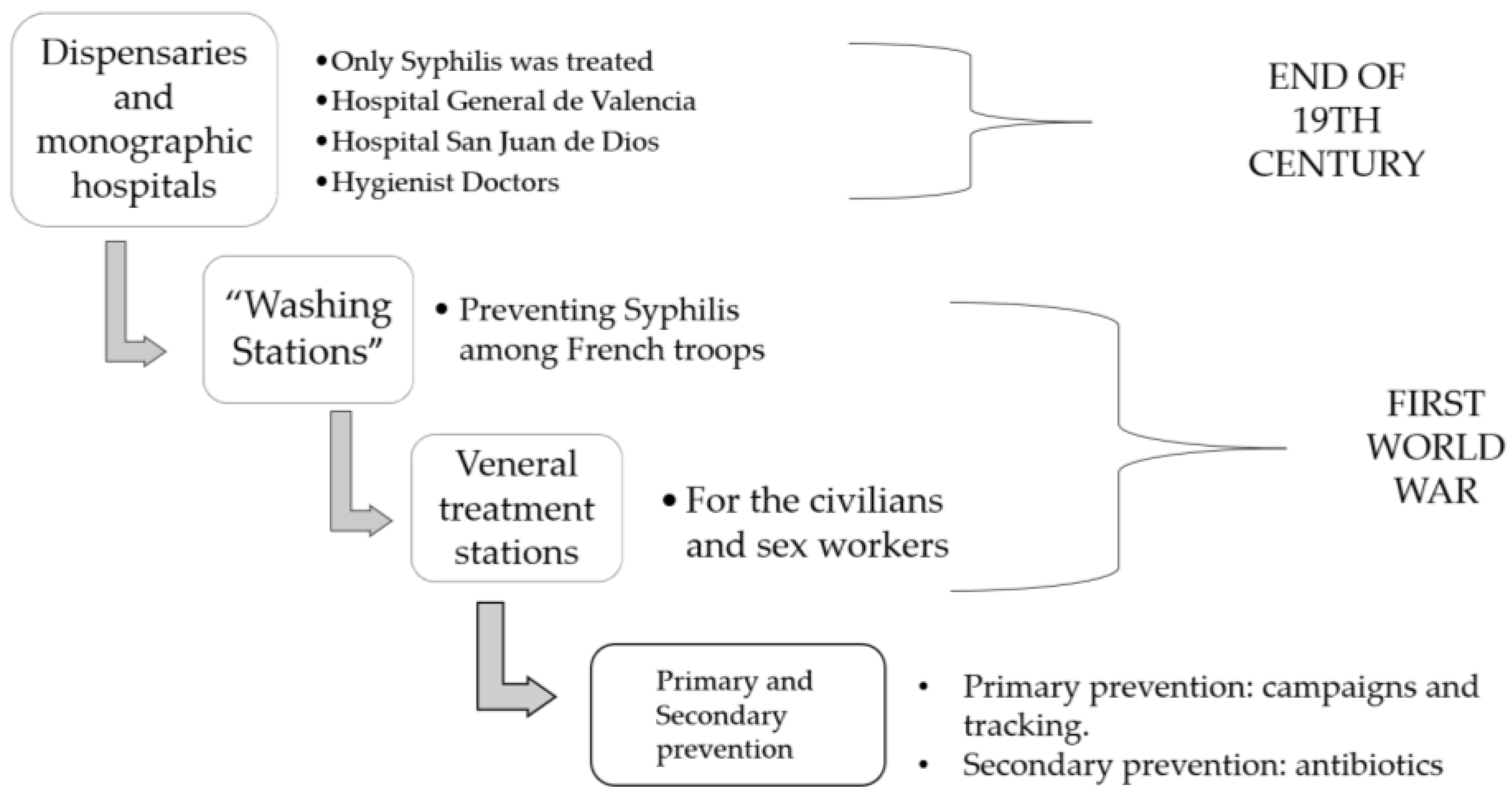

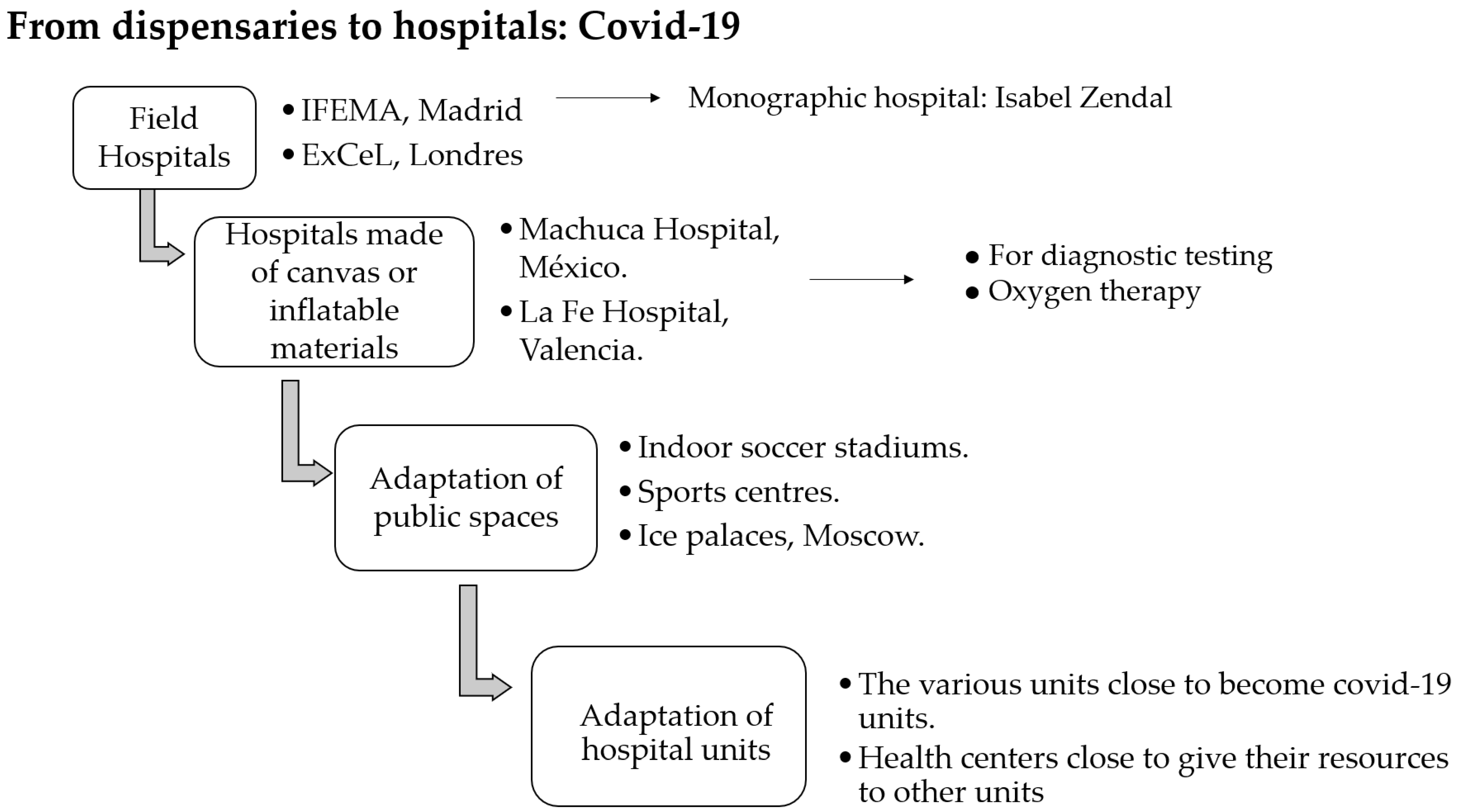

3.2. From Clinics to Hospitals

3.3. Treatments Applied to Combat Two Pandemics and Notification of New Cases

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lasagabaster, M.A.; Maider; Guerra, L.G. Sífilis. Enferm. Infecc. Y Microbiol. Clínica 2019, 37, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto de Salud Carlos III—ISCIII. Available online: https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Documents/PROTOCOLOS/Protocolo%20de%20Vigilancia%20de%20Sífilis.pdf#search=sifilis (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Infecciones de Transmisión Sexual. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (OPS/OMS). Sífilis. Available online: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14869:sti-syphilis&Itemid=3670&lang=es#:~:text=Se%20trata%20de%20una%20infección,transmisión%20maternoinfantil%20durante%20el%20embarazo (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/20220113_MICROBIOLOGIA.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Sistema Nacional de Saúde (SNS24). COVID-19. Available online: https://www.sns24.gov.pt/tema/doencas-infecciosas/covid-19/#sec-1 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- WHO. Preguntas y Respuestas Sobre la Transmisión de la COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted#:~:text=El%20virus%20puede%20propagarse%20a,pequeñas,%20o%20«aerosoles» (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- SciELO—Scientific Electronic Library Online. Signos y Síntomas Clínicos Asociados a COVID-19: Un Estudio Transversal. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0718-381X2022000100112&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Bhatia, G.; Dutta, P.K.; McClure, J. Coronavirus en el Mundo: Las últimas cifras, gráficos y Mapas. Reuters, 14 September 2020. Available online: https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/es/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Tampa, M.; Sarbu, I.; Matei, C.; Benea, V.; Georgescu, S.R. Brief history of syphilis. J. Med. Life 2014, 7, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Volcy, C. Sífilis: Neologismos, impacto social y desarrollo de la investigación de su naturaleza y etiología. IATREIA 2013, 27, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armelagos, G.J.; Zuckerman, M.K.; Harper, K.N. The science behind pre-Columbian evidence of syphilis in Europe: Research by documentary. Evol. Anthr. Issues News Rev. 2012, 21, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Vivancos, C.; González-Hernández, M.; Navarro-Gracia, J.F.; Sánchez-Payá, J.; González-Torga, A.; Portilla-Sogorb, J. Evolución del tratamiento de la sífilis a lo largo de la historia [Evolution of treatment of syphilis through history]. Rev. Española Quimioter. 2018, 31, 485–492. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sánchez, N.F.; Salas-Coronado, R. Origin, structural characteristics, prevention measures, diagnosis, and potential drugs to prevent and COVID-19. Medwave 2020, 20, e8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, L.; Amador-Bedolla, C.; Domínguez, L.; Amador-Bedolla, C. El origen de COVID-19: Lo que se sabe, lo que se supone y (muy poquito) sobre las teorías de complot. Educ. Química 2020, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeu, A.; Ollé, E. COVID-19: Descifrando el Origen. Available online: http://lhblog.nuevaradio.org/b2-img/Articulo_COVID19_ESPENG.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles González, J.; Solano Ruiz, C. El Modelo Estructural Dialéctico de los Cuidados: Una guía facilitadora de la organización, análisis y explicación de los datos en investigación cualitativa. In Proceedings of the Congresso Ibero-Americano em Investigação Qualitativa CIAIQ2016, Porto, Portugal, 12–14 July 2016; Volume 2, pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Siles González, J. La eterna guerra de la identidad enfermera: Un enfoque dialéctico y deconstruccionista. Index Enfermería 2005, 14, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles González, J. La construcción social de la Historia de la Enfermería. Index Enfermería 2004, 13, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles, J. Cultural History of Nursing: Epistemological and Epidemiological Reflection. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 18, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.E.; Romanowski, B. Syphilis: Review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caramés, M.; Valentí, X. Vergonya, Estigma i por: La història de les Malalties Vergonyoses. Dialnet. 2022. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8180697 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Hidalgo, M.C. COVID-19: La lucha invisible contra la ignorancia y el estigma. Index Enfermería 2020, 29, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva Baselga, S. Infecciones y Estigmas: Lecciones de la Pandemia del VIH Para el Mañana de la COVID-19. The Conversation. 2020. Available online: http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/155277/1/Infecciones%20y%20estigmas_%20lecciones%20de%20la%20pandemia%20del%20VIH%20para%20el%20man%cc%83ana%20de%20la%20COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Ventura, D. Migrações Internacionais e a Pandemia de COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.usp.br/directbitstream/04b3ca3e-828a-4f43-bd0f-cb4b3fdaa279/miginternacional.pdf#page=95 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Mendizábal, D.A. Analogía Filosófica. 2021. Available online: https://www.uv.mx/personal/ramlopez/files/2018/04/ANALOGIAXXXVa.pdf#page=117 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Paixão, G.; Silva, R.; Carneiro, F.; Lisbôa, L. The Pandemic of the New Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and Its Repercussions on Stigmatization and Prejudice. 2021. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/resource/pt/covidwho-1328345 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Iommi Echeverría, V. Girolamo Fracastoro y la Invención de la Sífilis. 2008. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3861/386138051002.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- García Ruiz, A.; Pablo Gormaz, R.; Marro Hernández, D.; Ezpeleta Esteban, L.; Bellostas Muñoz, P.; Coll Ercilla, M. Actuación Enfermera en la Prevención de Enfermedades de Transmisión Sexual. Una Revisión Bibliográfica. Revista Sanitaria de Investigación. 2022. Available online: https://revistasanitariadeinvestigacion.com/actuacion-enfermera-en-la-prevencion-de-enfermedades-de-transmision-sexual-una-revision-bibliografica/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Available online: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/12060/v37n2p193.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Revista Medica Sinergia. Vista de Sífilis: Abordaje Clínico y Terapéutico en Primer Nivel de Atención. Available online: https://revistamedicasinergia.com/index.php/rms/article/view/559/925 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Atención Primaria Práctica. Sífilis, a Propósito del Aumento de Casos en la Consulta. Elsevier|Una Empresa de Análisis de la Información|Empowering Knowledge. Available online: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-atencion-primaria-practica-24-articulo-sifilis-proposito-del-aumento-casos-S2605073019300604 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Berdasquera Corcho, D.; Rodríguez Gonzalez, I. El Médico de Familia y el Control de la Sífilis Después de una Estrategia de Intervención. 2006. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-21252006000300008#:~:text=Despu%C3%A9s%20de%20finalizada%20la%20intervenci%C3%B3n,muestran%20en%20la%20tabla%202 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Tranche Iparraguirre, S.; Martín Álvarez, R.; Párraga Martínez, I.; Tranche Iparraguirre, S.; Martín Álvarez, R.; Párraga Martínez, I. El Reto de la Pandemia de la COVID-19 Para la Atención Primaria. 2021. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1699-695X2021000200008 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Sacristán, J.; Millan, J. El Médico Frente a la COVID-19: Lecciones de una Pandemia. Educación Médica. 2020. Available online: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-educacion-medica-71-avance-resumen-el-medico-frente-covid-19-lecciones-S1575181320300747 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Zárate Grajales, R.; Ostiguín Meléndez, R.; Rita Castro, A.; Blas Valencia Castillo, F. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/510824689/Enfermeria-y-Covid# (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Ugarte Gurrutxaga, M.; Gomez Cantarino, M.; Molina Gallego, B. Nursing Care in the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Spanish Health System. 2020. Available online: https://ruidera.uclm.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10578/28108/Nursing%20Care%20in%20the%20Covid-19%20Pandemic%20in%20the%20Spanish%20Health%20System.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Chilamakuri, R.; Agarwal, S. COVID-19: Characteristics and Therapeutics. Cells 2022, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revista de Patologia Respiratoria. Available online: https://repositorio.uta.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/36760/1/Martinez%20Escobar%20Karla%20Estefania.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Rodríguez Cebeiro, M. Psicólogos en el Frente: La Atención Durante la Crisis del COVID-19. De las Emociones Tóxicas a la Salud Psicológica. Arch. Med. 2021, 21, 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. COVID-19. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Cunha-Oliveira, A.; Silva, M.; Afonso, M.; Peres, M.; Santos, T.; Queirós, P. Organización de los Servicios de Salud en Portugal a Principios del Siglo XX: El Caso de la Sífilis. Dialnet. 2022. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8452263 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Cunha-Oliveira, A. Para uma História do VIH/Sida em Portugal e os 30 Anos da Epidemia (1983–2013); Coleção Ciências e Culturas; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; Volume 23, 122p. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, E.; Fernadez Flores, A.; Mones, A.; Moreno, J.C. III Seminario de Historia de la Dermatología. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eduardo-Fonseca-2/publication/336041338_III_Seminario_de_Historia_de_la_Dermatologia_Siguenza_Guadalajara_6_de_noviembre_de_2018/links/5d8bd65ca6fdcc25549a424e/III-Seminario-de-Historia-de-la-Dermatologia-Sigueenza-Guadalajara-6-de-noviembre-de-2018.pdf#page=57 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Candel, F.; Canora, J.; Zapatero, A.; Barba, R.; González del Castillo, J.; García-Casasola, G.; San-Román, J.; Gil-Prieto, R.; Barreiro, P.; Fragiel, M.; et al. Temporary hospitals in times of the COVID pandemic. An example and a practical view. Rev. Española Quimioter. 2021, 34, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comunidad de Madrid. Hospital de Emergencias Enfermera Isabel Zendal. 2022. Available online: https://www.comunidad.madrid/centros/hospital-emergencias-enfermera-isabel-zendal (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Nuño González, A.; Magaletskyy, K.; Martín Carrillo, P.; Lozano Masdemont, B.; Mayor Ibarguren, A.; Feito Rodríguez, M.; Herranz Pinto, P. ¿Son las alteraciones en la mucosa oral un signo de COVID-19? Estudio transversal en un Hospital de Campaña. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2021, 112, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevia, V.; Lorca, J.; Hevia, M.; Domínguez, A.; López-Plaza, J.; Artiles, A.; Álvarez, S.; Sánchez, Á.; Fraile, A.; López-Fando, L.; et al. Pandemia COVID-19: Impacto y reacción rápida de la Urología. Actas Urológicas Españolas 2020, 44, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Afonso, M.; Silva, M.; Aparecida Peres, A.; Dominguez Isabel, P.; Espina Jerez, B.; Cunha-Oliveira, A. Preparados Curativos Aplicados por Sanitarios al Sifilítico: Un Recorrido Histórico (s. XVI-XXI). Temperamentvm. 2022. Ciberindex.com. Available online: http://ciberindex.com/index.php/t/article/view/e18038d/e18038d (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Pestoni Porvén, C.; Lado Lado, F.; Cabarcos Ortíz de Barrón, A.; Sánchez Aguilar, D. Sífilis: Perspectivas terapéuticas actuales. An. Med. Interna 2002, 19, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, R. Vista de Sifilis y Penicilina. 1945. Available online: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/revfacmed/article/view/26359/26694 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Guimaraes, K. El Desabastecimiento de Penicilina Pone en Jaque a la Salud Mundial. 2022. Available online: https://www.saludyfarmacos.org/lang/es/boletin-farmacos/boletines/ago201702/20_desa/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Rodriguez Nozal, R. El Despacho de Penicilina en la España de las Restricciones y el Estraperlo. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271824004_El_despacho_de_penicilina_en_la_Espana_de_las_restricciones_y_el_estraperlo (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Ren, M.; Dashwood, T.; Walmsley, S. The Intersection of HIV and Syphilis: Update on the Key Considerations in Testing and Management. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2021, 18, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Coronado, M.; Jaime-Pérez, J.; Villarreal-Martínez, A.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; Gómez-Almaguer, D. Successful second outpatient autologous hematopoietic cell transplant for relapsed POEMS syndrome in a patient with coexisting HIV, HBV and syphilis infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transpl. Immunol. 2021, 67, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndwandwe, D.; Wiysonge, C. COVID-19 vaccines. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 71, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério de Sanidad. Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias Sanitarias. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/20211015_INMUNIDAD_y_VACUNAS.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Ullrich, A.; Schranz, M.; Rexroth, U.; Hamouda, O.; Schaade, L.; Diercke, M.; Boender, T. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated non-pharmaceutical interventions on other notifiable infectious diseases in Germany: An analysis of national surveillance data during week 1–2016—Week 32–2020. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 19, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, J.; Caylà, J.; Millet, J. Estudio de contactos en infectados por SARS-CoV-2. El papel fundamental de la Atención Primaria y de la Salud Pública. COVID-19 En Atención Primaria 2020, 46, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Sanidad; Consumo y Bienestar Social; Portal Estadístico del SNS; Sistema de Información Sanitaria del SNS; Nivel de Salud y Estilos de vida. Enfermedades de Declaración Obligatoria. 2022; Sanidad.gob.es. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/declarObligatoria.htm (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- UNESCO. La Discriminación y el Estigma Relacionados con el COVID-19: ¿un Fenómeno Mundial? 2022. Available online: https://es.unesco.org/news/discriminacion-y-estigma-relacionados-covid-19-fenomeno-mundial (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Mendoza, D.A.; Bedoya, W.A. 2 Seguimiento de Enfermería a Neonatos con Sífilis Congénita: Una Revisión Narrativa de la Literatura, 2015–2020. 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.unicordoba.edu.co/bitstream/handle/ucordoba/4230/Acosta%20Mendoza%2c%20Danna%20Marcela%20Anaya%20Bedoya%2c%20Wendy%20Jhoana.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- López Terrada, M. El Tratamiento de la Sífilis en un Hospital Renacentista: La sala del mal de Siment del Hospital General de Valencia. 1989. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/26239 (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Almady Sánchez, E. Sífilis Venérea: Realidad Patológica, Discurso Médico y Construcción Social. Siglo xvi. 2021. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/cuicui/v17n49/v17n49a10.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Informe Semanal de Vigilancia Epidemiológica en España. 2022. Isciii.es. Available online: https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Boletines/Documents/Boletin_Epidemiologico_en_red/boletines%20en%20red%202022/IS_N%C2%BA20-20220517_WEB.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 Map. 2022. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Bonato, F.; Ferreli, C.; Satta, R.; Rongioletti, F.; Atzori, L. Syphilis and the COVID-19 pandemic: Did the lockdown stop risky sexual behavior? Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 39, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarin-Vicente, E.; Sendagorta Cudos, E.; Servera Negre, G.; Falces Romero, I.; Ballesteros Martin, J.; Martin-Gorgojo, A.; Comunion Artieda, A.; Salas Marquez, C.; Herranz Pinto, P. Infecciones de transmisión sexual (ITS) durante el estado de alarma por la pandemia de COVID-19 en España. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2022, 113, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Hontangas, J.; Frasquet Artes, J. Seimc.org. Available online: https://www.seimc.org/contenidos/ccs/revisionestematicas/serologia/sifilis.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Cañelles López, M.; Jimenez Sarmiento, M.; Campillo, N. ¿Podemos saber cuándo surgió el primer caso de COVID-19? The Conversation. 2019. Available online: https://theconversation.com/podemos-saber-cuando-surgio-el-primer-caso-de-covid-19-163275 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Ena, J. Telemedicina aplicada a COVID-19. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2020, 220, 472–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. Antibiotics for syphilis diagnosed during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2001, 2010, CD001143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiiza, P.; Mullin, S.; Teo, K.; Adhikari, N.; Fowler, R. Treatment of Ebola-related critical illness. Intensiv. Care Med. 2020, 46, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La OMS Recomienda un Tratamiento Sumamente Eficaz Contra la COVID-19 y pide a la Empresa Productora Amplia Distribución Geográfica y Transparencia. 2022. Who.int. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/22-04-2022-who-recommends-highly-successful-covid-19-therapy-and-calls-for-wide-geographical-distribution-and-transparency-from-originator (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- European Medicines Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/paxlovid-epar-product-information_pt.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Stanford, K.; Almirol, E.; Schneider, J.; Hazra, A. Rising Syphilis Rates during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2021, 48, e81–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. La Agenda Para el Desarrollo Sostenible—Desarrollo Sostenible (No Date) United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/development-agenda/ (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- María Luisa Marinho, C.C. Dos Años de Pandemia de COVID-19 en América Latina y el Caribe: Reflexiones para Avanzar Hacia sistemas de Salud y de Protección Social Universales, Integrales, Sostenibles y Resilientes; Documentos de Proyectos (LC/TS.2022/63); Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2022; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/47914/1/S2200413_es.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Sapaico Del Castillo, C.A.; Martínez Puma, E.; Gonzales Portugal, N. Pandemia por COVID-19; Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar: Ciudad de México, México, 2021; Volumen 5, p. 1628. ISSN 2707-2207/ISSN 2707-2215. Available online: https://ciencialatina.org/index.php/cienciala/article/view/373 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Colás, B. Retos de la Investigación Educativa tras la pandemia COVID-19. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2021, 39, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

| Differences | Syphilis | COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Infection caused | Bacterium Treponema pallidum, which belongs to the Spirochaete family [1] | SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19, it belongs to the genus Beta coronavirus and is part of the family Coronavirinae [5] |

| Disease characteristics | Syphilis can develop in three stages:

| COVID-19 signs and symptoms are fever above 38 °C, cough, headache, muscle pain, dyspnea, anosmia, and ageusia, although others such as conjunctivitis and arthralgias may occur [8]. In some cases, “long COVID” or post-COVID symptoms may arise [39]. |

| Syphilis | COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| Year | 1493 [3] | 2019 [5] |

| Timelines of Syphilis and COVID-19 | 1552: St. John of God Hospital achieved worldwide fame and was considered one of the best health centers for the mercurial treatments applied to treat syphilis [40,41]; 1623: Philip IV, King of Spain, banned prostitution to prevent the further spread of these diseases [40,41]; 1870: Syphilis was rife in hospitals, infirmaries, and surgeries. In World War I, the rise of this disease meant that thousands of soldiers were infected [40,41]; 1910: A team of medical hygienists was formed to take sex workers to antivenereal dispensaries [40,41]; 1918: The presence of syphilis was still strong among the population, which led to the creation of “venereal treatment stations for soldiers and civilians” as a prophylactic measure [40,41]. | 2019 and 2020: Field hospitals were set up all over the world to combat the disease. Primary care centers were even closed to allocate these resources. Telematic consultations were realized [44,45]. Hospitals had to close most of their wards to convert them into COVID-19 units, and all other nonemergency activities ceased [46]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunha-Oliveira, A.; de Brito Pinto, T.K.; Pereira Afonso, M.R.; de Almeida Peres, M.A.; Pina Queirós, P.J.; Santos, D.G.; Gómez-Cantarino, M.S. Perspective on Two Major Pandemics: Syphilis and COVID-19, a Scoping Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076073

Cunha-Oliveira A, de Brito Pinto TK, Pereira Afonso MR, de Almeida Peres MA, Pina Queirós PJ, Santos DG, Gómez-Cantarino MS. Perspective on Two Major Pandemics: Syphilis and COVID-19, a Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):6073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076073

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha-Oliveira, Aliete, Talita Katiane de Brito Pinto, Mónica Raquel Pereira Afonso, Maria Angélica de Almeida Peres, Paulo Joaquim Pina Queirós, Diana Gabriela Santos, and Maria Sagrario Gómez-Cantarino. 2023. "Perspective on Two Major Pandemics: Syphilis and COVID-19, a Scoping Review" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 6073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076073

APA StyleCunha-Oliveira, A., de Brito Pinto, T. K., Pereira Afonso, M. R., de Almeida Peres, M. A., Pina Queirós, P. J., Santos, D. G., & Gómez-Cantarino, M. S. (2023). Perspective on Two Major Pandemics: Syphilis and COVID-19, a Scoping Review. Sustainability, 15(7), 6073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076073