Asymmetric Effects of Human Health Capital on Economic Growth in China: An Empirical Investigation Based on the NARDL Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Hypothesis Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. The Model and Methods

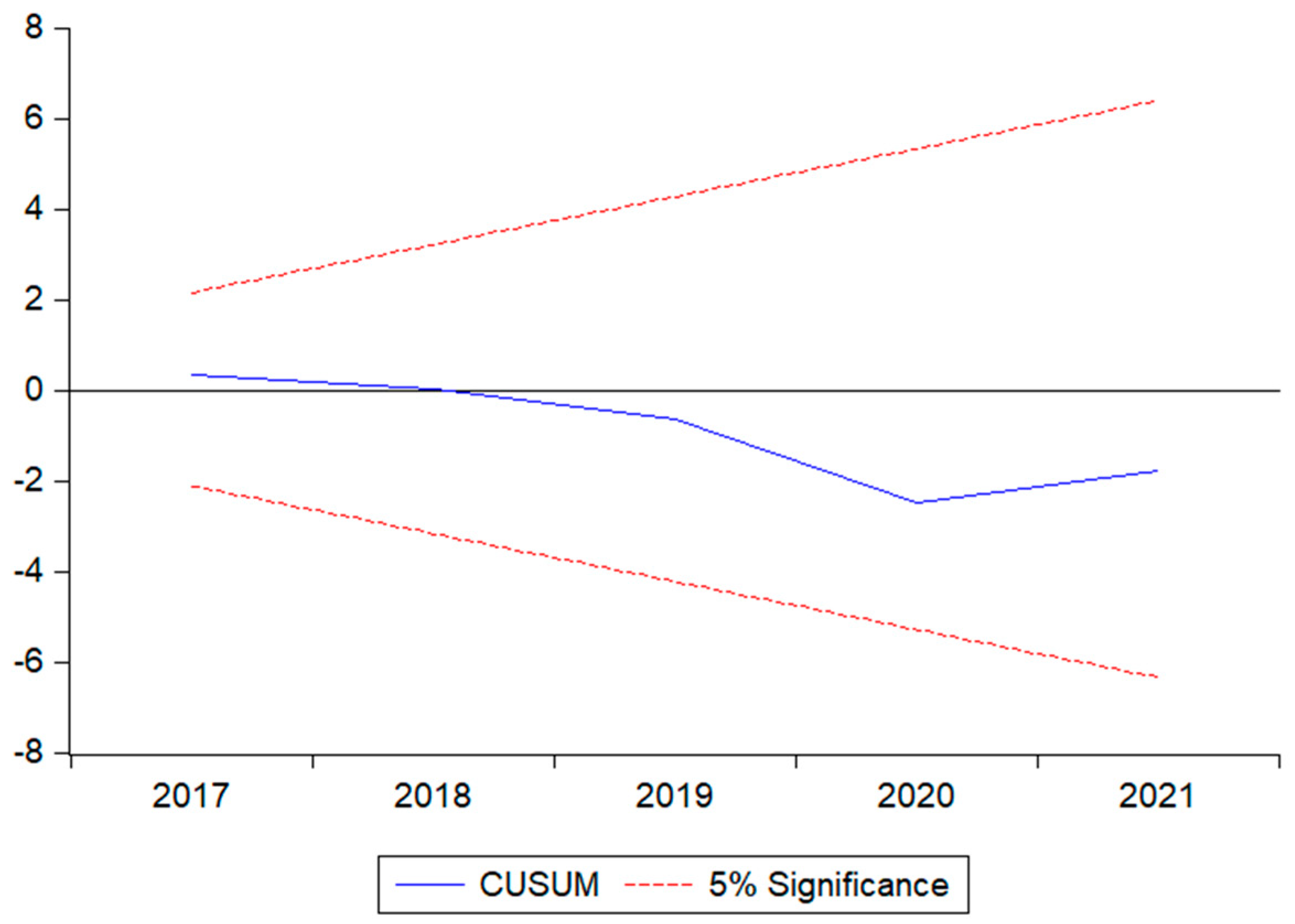

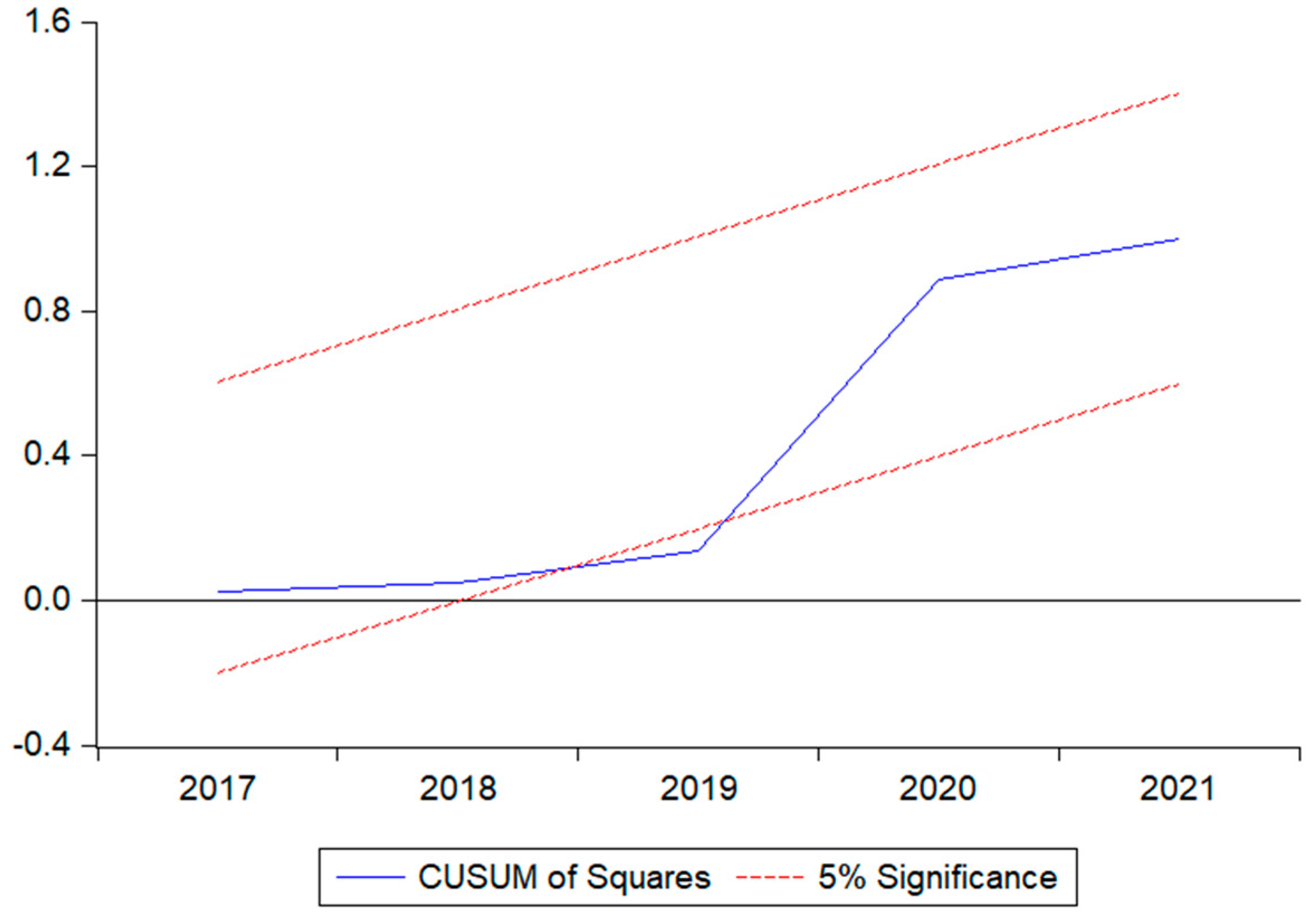

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, F.; Lv, J.H.; Wang, H.L.; Gao, J.; Zhou, Z. Expanding public health in China: An empirical analysis of healthcare inputs and outputs. Public Health 2017, 142, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Nguyen-Thi-Lan, H.; Nguyen-Manh, D.; Tran-Duc, H.; To-The, N. Analyzing the status of multidimensional poverty of rural households by using sustainable livelihood framework: Policy implications for economic growth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 16106–16119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Kuhn, M.; Prettner, K.; Bloom, D.E.; Wang, C. Macro-level efficiency of health expenditure: Estimates for 15 major economies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 287, 114270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, R. The relationship between health and GDP in OECD countries in the very long run. Health Econ. 2011, 20, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.; Canning, D. Health as human capital and its impact on economic performance. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2003, 28, 304–315. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41952692 (accessed on 26 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, H. Health, human capital, and development. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2010, 2, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacci, E.; Clements, B.; Gupta, S.; Cui, Q. Social spending, human capital, and growth in developing countries. World Dev. 2008, 36, 1317–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. Health and Economic Growth; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Health expenditure, human capital, and economic growth: An empirical study of developing countries. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2020, 20, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, W.; Lewis, M. Health Investments and Economic Growth: Macroeconomic Evidence and Microeconomic Foundations; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/963481468149697269/pdf/WPS4877.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Öztürk, S.; Topçu, E. Health expenditures and economic growth evidence from G8 countries. Int. J. Econ. Empir. Res. 2014, 2, 256–261. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11787/3612 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Bloom, D.E.; Kuhn, M.; Prettner, K. Health and Economic Growth. Oxford Res. Encycl. Econ. Financ. 2019. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/economics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-36;jsessionid=DDA12C348CE29C4F4426F3636AE740F8 (accessed on 12 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.H.; Alam, K.; Gow, J. Health expenditure and gross domestic product: Causality analysis by income level. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2020, 20, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilgan, E.; Kilic, D.; Ertugrul, H.M. The dynamic relationship between health expenditure and economic growth: Is the health-led growth hypothesis valid for Turkey? Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017, 18, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghupathi, V.; Raghupathi, W. Healthcare expenditure and economic performance: Insights from the United States Data. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengin, A.K. The relationship between health expenditures and economic growth: Turkish case. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Res. 2012, 3, 404–409. Available online: http://www.ijbmer.com/docs/volumes/vol3issue1/ijbmer2012030101.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Kurt, S. Government health expenditures and economic growth: A Feder-Ram approach for the case of Turkey. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2015, 5, 441–447. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijefi/issue/31969/352142?publisher=http-www-cag-edu-tr-ilhan-ozturk (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Wang, F. More health expenditure, better economic performance? Empirical evidence from OECD countries. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2015, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpundu, M.; Mwafulirwa, J.; Chaampita, M.; Salwindi, N. Effects of Public Expenditure on Gross Domestic Product in Zambia from 1980–2017: An ARDL Methodology Approach. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2019, 11, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggoh, J.; Houeninvo, H.; Sossou, G.A. Education, health and economic growth in African countries. J. Econ. Dev. 2015, 40, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Liu, X. Health expenditures, environmental quality, and economic development: State-of-the-art review and findings in the context of COP26. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 954080. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.954080/full (accessed on 12 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Natalini, J.G.; Segal, L.N. Lung microbial-host interface through the lens of multi-omics. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well, D.N. Accounting for the effect of health on economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 1265–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, A. Does health capital have differential effects on economic growth? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2013, 20, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi Biggs, B.; King, L.; Basu, S.; Stuckler, D. Is wealthier always healthier? The impact of national income level, inequality, and poverty on public health in Latin America. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piabuo, S.M.; Tieguhong, J.C. Health expenditure and economic growth—A review of the literature and an analysis between the economic community for central African states (CEMAC) and selected African countries. Health Econ. Rev. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akingba, I.O.I.; Kaliappan, S.R.; Hamzah, H.Z. Impact of health capital on economic growth in Singapore: An ARDL approach to cointegration. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2018, 45, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayadevan, C.M. Impacts of health on economic growth: Evidence from structural equation modelling. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2021, 5, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, E.; Celik Kecili, M. Economic growth and health expenditure analysis for Turkey: Evidence from time series. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 1786–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, T.; Dey, S.R.; Tareque, M. Exploring the linkage between human capital and economic growth: A look at 141 developing and developed countries. Econ. Syst. 2022, 46, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, E.H.; Vahedi, S.; Teimourizad, A.; Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Hadian, M.; Pour, A.T. Comparison of the effects of public and private health expenditures on the health status: A panel data analysis in eastern mediterranean countries. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2013, 1, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, P.P. The black box of health care expenditure growth determinants. Health Econ. 1998, 7, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarti, S.; Terraneo, M.; Bordogna, M.T. Poverty and private health expenditures in Italian households during the recent crisis. Health Policy 2017, 121, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardim, M.S.; Cilingiroglu, N.; Yardim, N. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in Turkey. Health Policy 2010, 94, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krokeyi, W.S.; Niyekpemi, B.O. Human capital and economic growth nexus in Nigeria. J. Glob. Econ. Bus. 2021, 2, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomolafe, K.J.; Awoyemi, B.O.; Yusufu, F.O. The Effect of Private and Public Health Expenditure on Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2021, 27, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baicker, K.; Shepard, M.; Skinner, J. Public financing of the Medicare program will make its uniform structure increasingly costly to sustain. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.; Luo, X.; Luo, Y.; Wang, W. Public Health Services, Health Human Capital, and Relative Poverty of Rural Families. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, M.; Ray, D. Life expectancy effects of public and private health expenditures in OECD countries 1970–2012: Panel time series approach. Econ. Anal. Policy 2017, 56, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. Insuring against health shocks: Health insurance and household choices. J. Health Econ. 2016, 46, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K. Social insurance, private health insurance and individual welfare. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2017, 78, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthappu, M.; Ng, K.Y.B.; Williams, C.; Atun, R.; Zeltner, T. Government health care spending and child mortality. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e887–e894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Kamp, A. Health capital: Toward a conceptual framework for understanding the construction of individual health. Soc. Theory Health 2021, 19, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnon, J.; Pekarsky, B. Should Health Economic Evaluations Undertaken from a Societal Perspective Include Net Government Spending Multiplier Effects? Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2020, 18, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Yu, B.; Greenwood-Nimmo, M. Modelling Asymmetric Cointegration and Dynamic Multipliers in a Nonlinear ARDL Framework; Festschrift in honor of Peter Schmidt; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 281–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, S.; Qiao, Z. The Relationship Between “Protect People’s Livelihood” and “Promote the Economy:” Provincial Evidence from China. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 722062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatam, N.; Tourani, S.; Rad, E.H.; Bastani, P. Estimating the relationship between economic growth and health expenditures in ECO countries using panel cointegration approach. Acta Med. Iran. 2016, 54, 15091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, M.; Tisdell, J.; Canny, B.; Zimitat, C. Health care and the future of economic growth: Exploring alternative perspectives. Health Econ. Policy Law 2020, 15, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluko, O.O.; Aigbedion, I.M. Public health expenditure and economic growth in Nigeria: An error correction model. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2017, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haini, H. Spatial spillover effects of public health and education expenditures on economic growth: Evidence from China’s provinces. Post Communist Econ. 2020, 32, 1111–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Yew, S.L.; Ugur, M. Effects of government education and health expenditures on economic growth: A meta-analysis. Econstor 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110901 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Sengupta, S. Empirical evidence to the nonmonotonic relationship between public health expenditure and economic growth. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2022, 29, 49–62. Available online: http://store.ectap.ro/articole/1579.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Zheng, X.; Song, F.; Yu, Y.; Song, S. In Search of Fiscal Interactions: A Spatial Analysis of Chinese Provincial Infrastructure Spending. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2015, 19, 860–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduka, A.C.; Madichie, C.V.; Ekesiobi, C.S. Health care expenditure, health outcomes, and economic growth nexus in Nigeria: A Toda–Yamamoto causality approach. Unified J. Econ. Int. Financ. 2016, 2, 1–10. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319006465_Health_Care_Expenditure_Health_Outcomes_and_Economic_Growth_Nexus_in_Nigeria_A_Toda_-_Yamamoto_Causality_Approach (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Beylik, U.; Cirakli, U.; Cetin, M.; Ecevit, E.; Senol, O. The relationship between health expenditure indicators and economic growth in OECD countries: A Driscoll-Kraay approach. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisswani, K.M. The Dynamic Links between Oil Prices and Economic Growth: Recent Evidence from Nonlinear Cointegration Analysis for the ASEAN-5 Countries. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 3153–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, N.; Mohanty, S.; Das, A.; Sahoo, M. Health expenditure and economic growth nexus: Empirical evidence from South Asian countries. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 2, 0972150920963069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaies, B. Reassessing the impact of health expenditure on income growth in the face of the global sanitary crisis: The case of developing countries. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 1415–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndaguba, E.A.; Hlotywa, A. Public health expenditure and economic development: The case of South Africa between 1996 and 2016. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2021, 9, 1905932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Gil, M.; ElHichou-Ahmed, C.; Mata-García, A. Effects of Immigrants, Health, and Ageing on Economic Growth in the European Union. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atems, B. Public health expenditures, taxation, and growth. Health Econ. 2019, 28, 1146–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamanda, E.; Lanpin, Y.; Sesay, B. Causal nexus between health expenditure, health outcome and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa countries. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2022, 37, 2284–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedvicakova, M.; Pozdilkova, A.; Piwowar, A. Analysis of the Health Spending and GDP in the Visegrad Group and in the Germany. Hradec Econ. Days 2020, 10, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.F.; Chang, T.; Wang, C.M.; Wu, T.-P.; Lin, M.-C.; Huang, S.-C. Measuring the impact of health on economic growth using pooling data in regions of Asia: Evidence from a quantile-on-quantile analysis. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 689610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T. Sources of health financing and health outcomes: A panel data analysis. Health Econ. 2018, 27, 1996–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapuan, N.M.; Sanusi, N.A. Cointegration Analysis of Social Services Expenditure and Human Capital Development in Malaysia: A Bound Testing Approach. J. Econ. Coop. Dev. 2013, 34, 1–8. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286493630_Cointegration_analysis_of_social_services_expenditure_and_human_capital_development_in_Malaysia_A_bound_testing_approach (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Praise, U.A.I.; George-Anokwuru, C.C. Empirical analysis of determinants of human capital formation: Evidence from the Nigerian data. J. World Econ. Res. 2018, 7, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Singh, B.; Aru, W.S. Relationship between government expenditure and economic growth: Evidence from Vanuatu. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2022, 27, 640–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder Alan, C.; Solow Robert, M. Does Fiscal Policy Matter?/Econometric Research Program Research Memorandum No. 144 August 1972. Available online: http://www.princeton.edu/~erp/ERParchives/archivepdfs/M144.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Gemmell, N.; Kneller, R.; Sanz, I. Does the Composition of Government Expenditure Matter for Long-Run GDP Levels? Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2016, 78, 522–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdil, E.; Yetkiner, I.H. A Panel Data Approach for Income-Health Causality. 2004. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24130157_A_Panel_Data_Approach_for_Income-Health_Causality (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Palley, T.I. Keynesian, classical and new Keynesian approaches to fiscal policy: Comparison and critique. Rev. Political Econ. 2013, 25, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, G.N.; Adedoyin, F.F.; Bekun, F.V.; Agabo, T.J. Does life expectancy, death rate and public health expenditure matter in sustaining economic growth under COVID-19: Empirical evidence from Nigeria? J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Cong, X.; Zhu, Z. The efficiency of provincial government health care expenditure after China’s new health care reform. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.; Saidi, K. Environmental pollution, health expenditure and economic growth in the Sub-Saharan Africa countries: Panel ARDL approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, B.; Nketiah-Amponsah, E.; Owoo, N.S. Health and economic growth nexus: Evidence from selected sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. Global Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGDP | 44 | 19,423.14 | 23,714.88 | 385.00 | 81,370.00 | 1.191052 | 3.120067 |

| PHE | 44 | 4995.84 | 6127.359 | 22.52 | 21,205.67 | 1.258606 | 3.465875 |

| GHE | 44 | 4192.35 | 6337.955 | 35.44 | 21,941.90 | 1.505452 | 3.970711 |

| SSE | 44 | 6038.36 | 9440.012 | 52.25 | 34,963.26 | 1.740078 | 4.863360 |

| Variables | ADF Test | PP Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | First Difference | Level | First Difference | |

| PHE | 4.075927 (0.9999) | −6.613411 *** (0.0000) | 14.18989 (0.9999) | −12.54145 *** (0.0000) |

| GHE | −2.116825 (0.2396) | −5.683656 *** (0.0000) | 4.957534 (0.9999) | −13.35307 *** (0.0000) |

| SSE | −1.825528 (0.3623) | −3.185239 * (0.0289) | 12.60500 (0.9999) | −10.11902 *** (0.0000) |

| PGDP | 6.262191 (0.9999) | −7.761353 *** (0.0000) | 9.773890 (0.9999) | −5.308075 *** (0.0001) |

| Test Statistic | Value | Significant Level | I(0) | I(1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-statistic | 36.47189 *** | 10% | 1.99 | 2.94 |

| k | 6 | 5% | 2.27 | 3.28 |

| 2.5% | 2.55 | 3.61 | ||

| 1% | 2.88 | 3.99 |

| Regressors | Coefficient | t-Statistic | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.864623 *** | 10.87404 | 0.0001 | |

| 0.457396 | 1.923363 | 0.1124 | |

| 1.280368 *** | 5.630073 | 0.0024 | |

| 3.514629 ** | 3.929308 | 0.0111 | |

| 0.218079 | 0.164822 | 0.8755 | |

| −7.484464 *** | −4.562640 | 0.0060 | |

| −14.95590 *** | −7.121060 | 0.0008 | |

| −0.427581 | −0.484431 | 0.6486 | |

| 3.138878 * | 2.423853 | 0.0598 | |

| −10.98566 *** | −6.980852 | 0.0009 | |

| −12.00262 *** | −6.901572 | 0.0010 | |

| 5.975420 *** | 5.718229 | 0.0023 | |

| −8.084124 ** | −3.464927 | 0.0179 | |

| −5.557417 * | −2.227551 | 0.0764 | |

| 3.124636 | 0.429227 | 0.6856 |

| Panel A: Estimated Long-Term Coefficients | |||

| Regressors | Coefficient | t-Statistic | Probability |

| −3.059864 *** | −10.11325 | 0.0002 | |

| 4.016686 *** | 4.496772 | 0.0064 | |

| 11.85568 *** | 4.416770 | 0.0069 | |

| −13.23850 *** | −6.376866 | 0.0014 | |

| 6.112802 ** | 2.743920 | 0.0406 | |

| 17.63887 *** | 5.521861 | 0.0027 | |

| 14.15027 ** | 2.835459 | 0.0364 | |

| Panel B: Long Term Influence Coefficient | |||

| 1.312701 *** | |||

| 3.874577 *** | |||

| −4.326499 *** | |||

| 1.997737 ** | |||

| 5.764593 *** | |||

| 4.624477 ** | |||

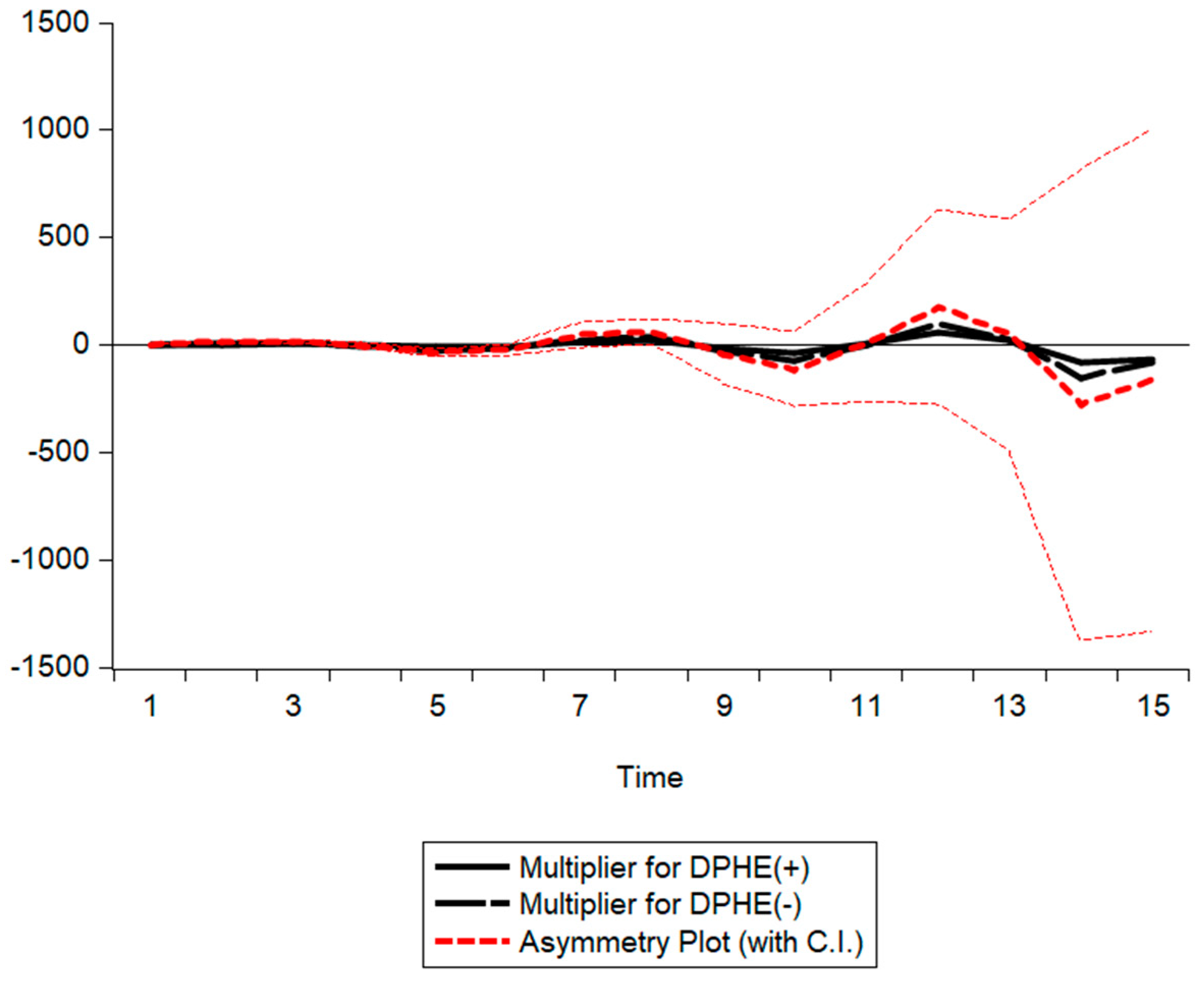

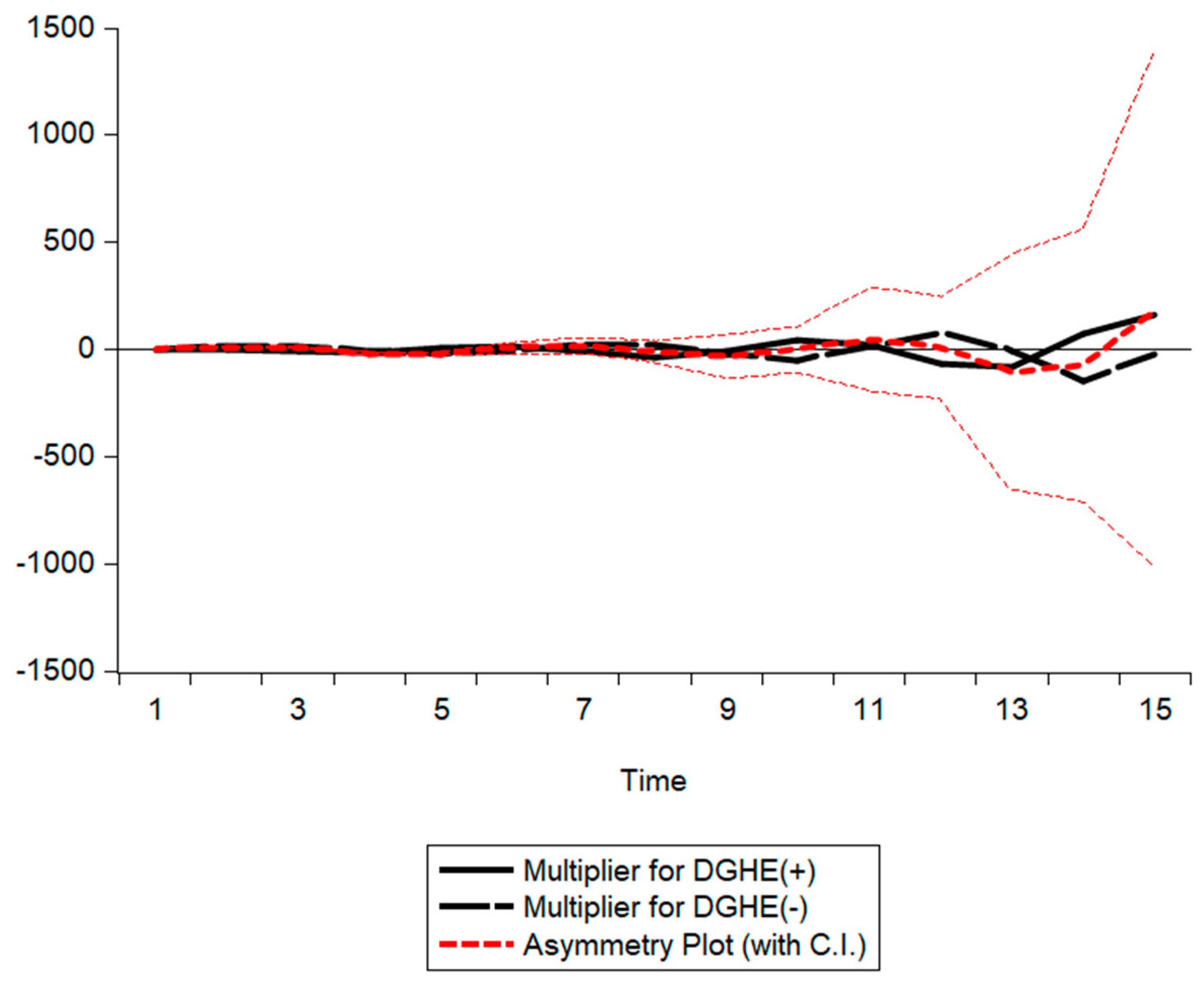

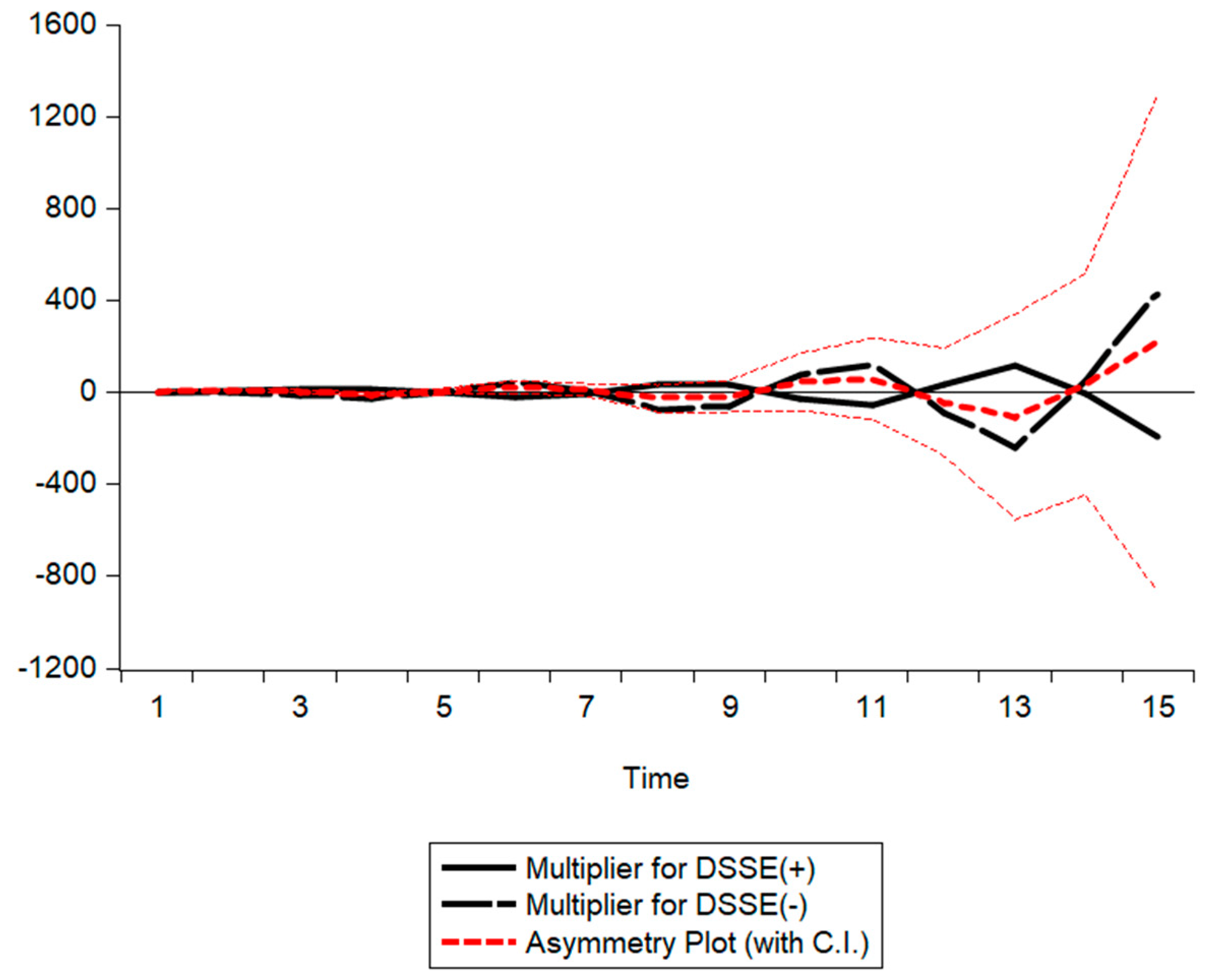

| PHE | GHE | SSE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wlr | −3.121189 ** (0.0262) | −5.092586 *** (0.0038) | 0.985638 (0.3696) |

| Wsr | 4.485434 *** (0.0065) | 7.368960 *** (0.0007) | 3.859679 ** (0.0119) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, W.; Wang, Y. Asymmetric Effects of Human Health Capital on Economic Growth in China: An Empirical Investigation Based on the NARDL Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065537

Jiang W, Wang Y. Asymmetric Effects of Human Health Capital on Economic Growth in China: An Empirical Investigation Based on the NARDL Model. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065537

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Wei, and Yadong Wang. 2023. "Asymmetric Effects of Human Health Capital on Economic Growth in China: An Empirical Investigation Based on the NARDL Model" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065537

APA StyleJiang, W., & Wang, Y. (2023). Asymmetric Effects of Human Health Capital on Economic Growth in China: An Empirical Investigation Based on the NARDL Model. Sustainability, 15(6), 5537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065537