Developing Adaptive Curriculum for Slum Upgrade Projects: The Fourth Year Undergraduate Program Experience

Abstract

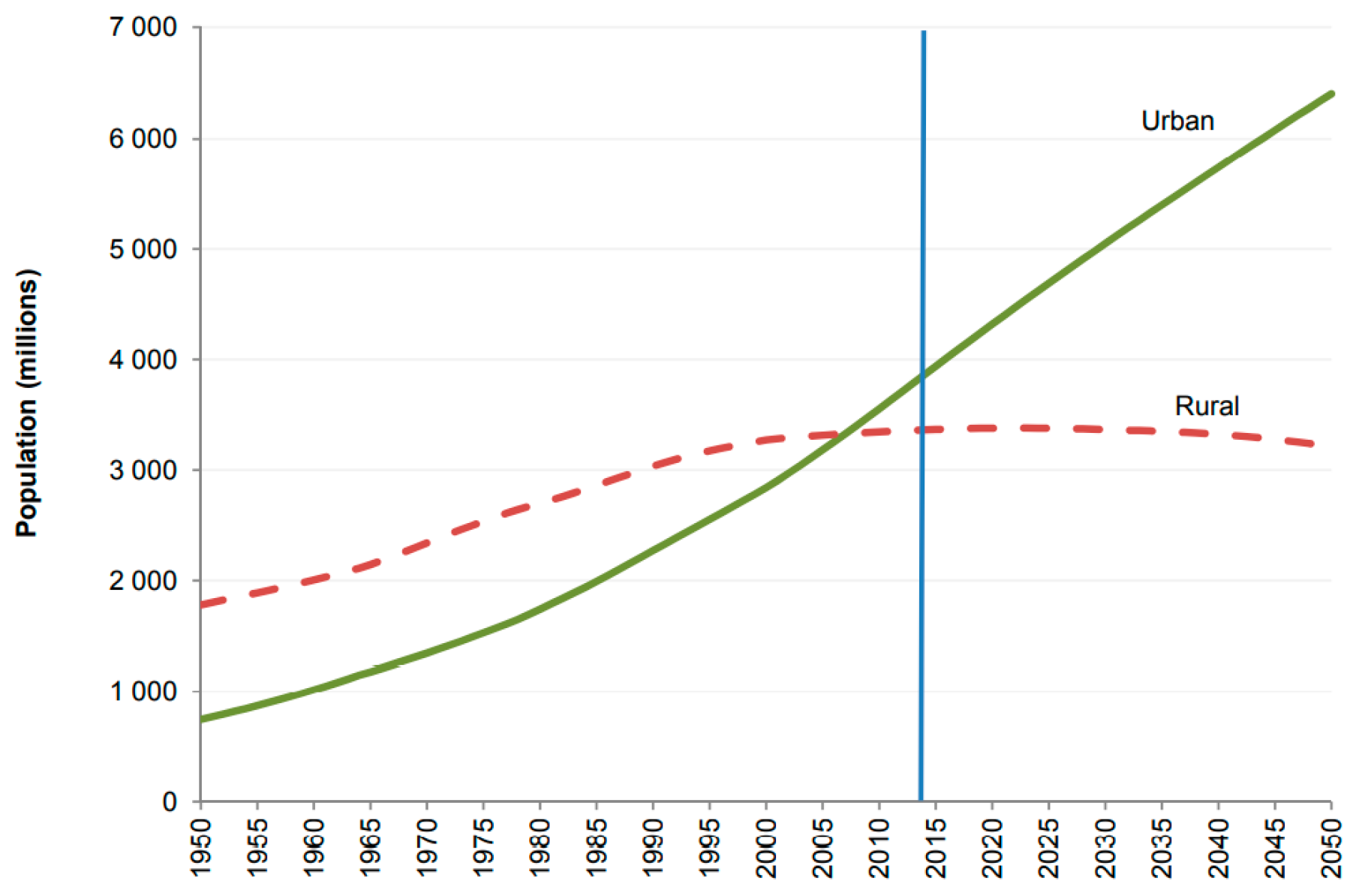

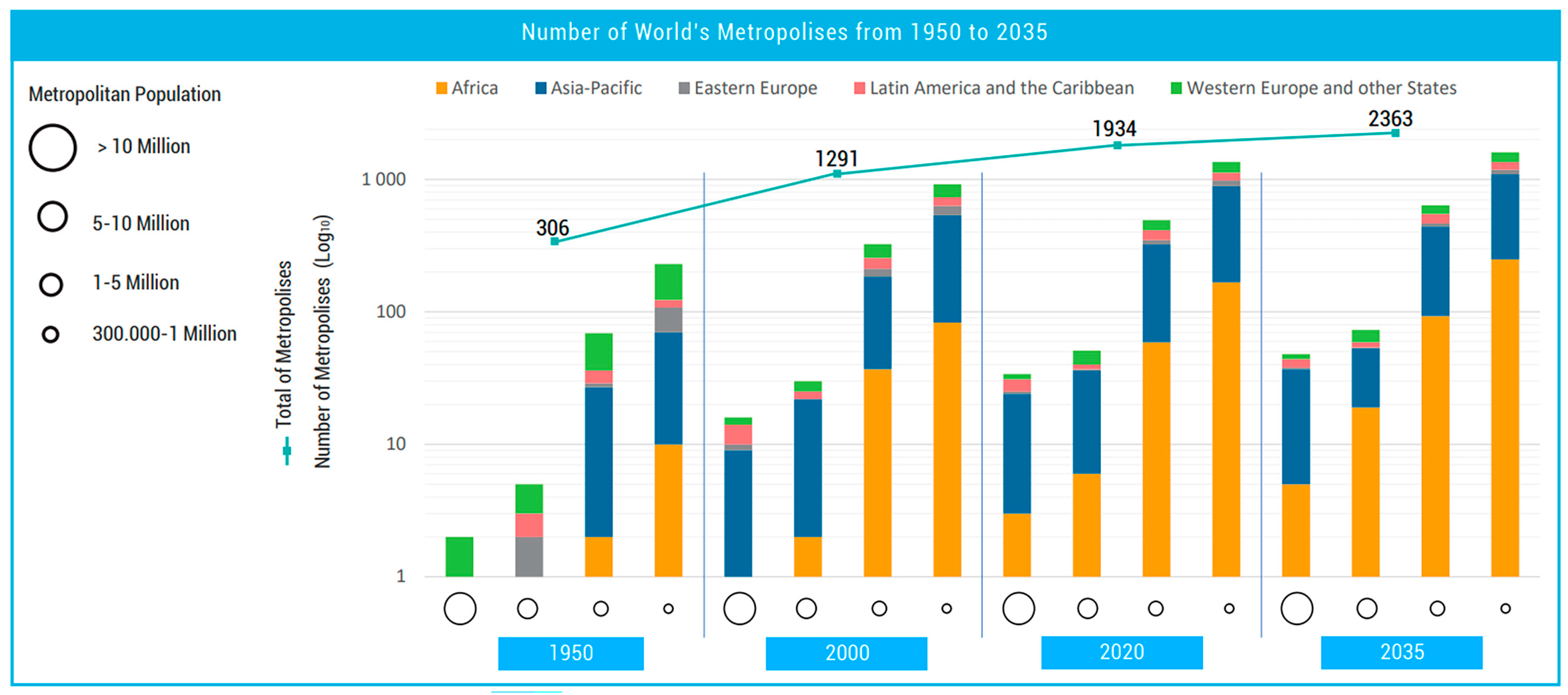

1. Introduction

Fourth Year Undergraduate Architecture Curriculum

- (1)

- In which way can the fourth year curriculum be modified in order to be responsive to the slum upgrading topic?

- (2)

- In which way can the fourth year curriculum be updated in order to be responsive to the principal social sustainability indicators such as social equity, well-being and quality of life?

2. Theoretical Framework: Architecture Education

2.1. Slum Topic in Architecture Education

2.2. Social Sustainability: An Overview

2.3. Social Sustainability in Architecture Education

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Research Process

3.3. Data Specification

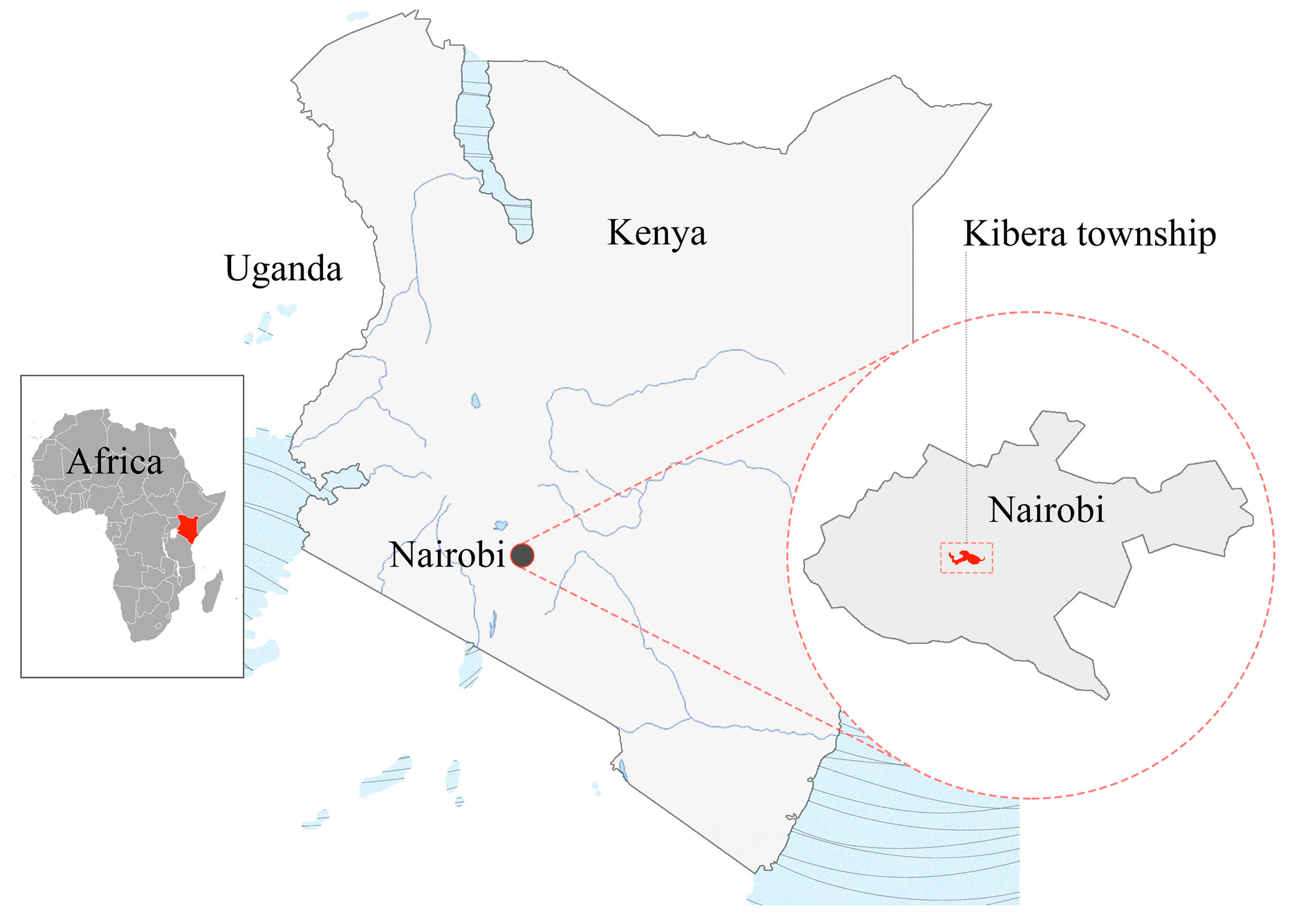

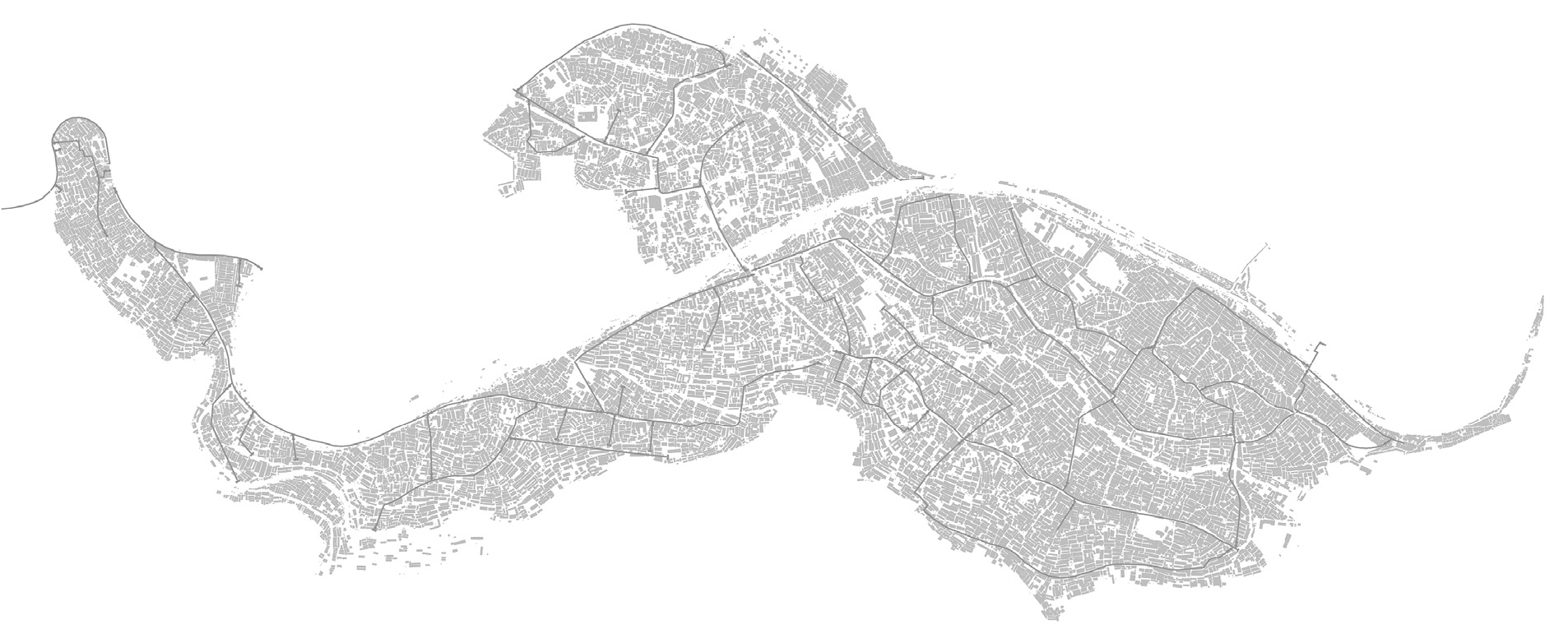

3.4. Research Context

3.5. Limitations

4. Research Design: Defining the Proposed Framework within the Fourth Year Architecture Curriculum

4.1. Graduation Research & Preparation (ARC 403) Course

- (1)

- Participant observation: this can be defined as the learning process through exposure to various everyday routines and activities of locals in their environment. Participant observation can assist the young architects in documenting the way the community is organized, how individuals relate to one another, where individuals congregate and socially engage with each other, the type of activities that the slum hosts and the way physical and social boundaries are organized. The principal role of the young architect is to be physically present in the slum, accompany the dwellers, observe their daily routines and ask questions [116];

- (2)

- Informal interviewing: this comprises long casual conversations with various individuals that the young architect encounters during fieldwork. The long conversations can be regarded as a form of partnership between the young architect and the locals as insiders of the community. The partnership’s outcome is to gain in-depth knowledge of the place [117]. Local slum dwellers can be regarded as key informants since they have inhabited the slum for an extended period. They have a vast knowledge of their environment and can pass their knowledge and know-how of the environment to the young architects [116,118]. The young architects are encouraged to record the narratives of the local people and engage in open-ended interviews if needed. In fact, slums, with their inherent complexity, require that the young architects as researchers expose themselves to the actual context, which involves actual individuals [23,119];

- (3)

- Walking and observing the site: the young architects are asked to walk in and around the site to understand/explore the site. They are required to walk the same routes locals use and record the existing pathways; the local pathways are the product of local people as frequent users. Walking slowly can be regarded as a tool for exploring the environment; it allows the observer to record existing details in the environment. Walking and observing the site unfolds its hidden inherent potential to the observer [120];

- (4)

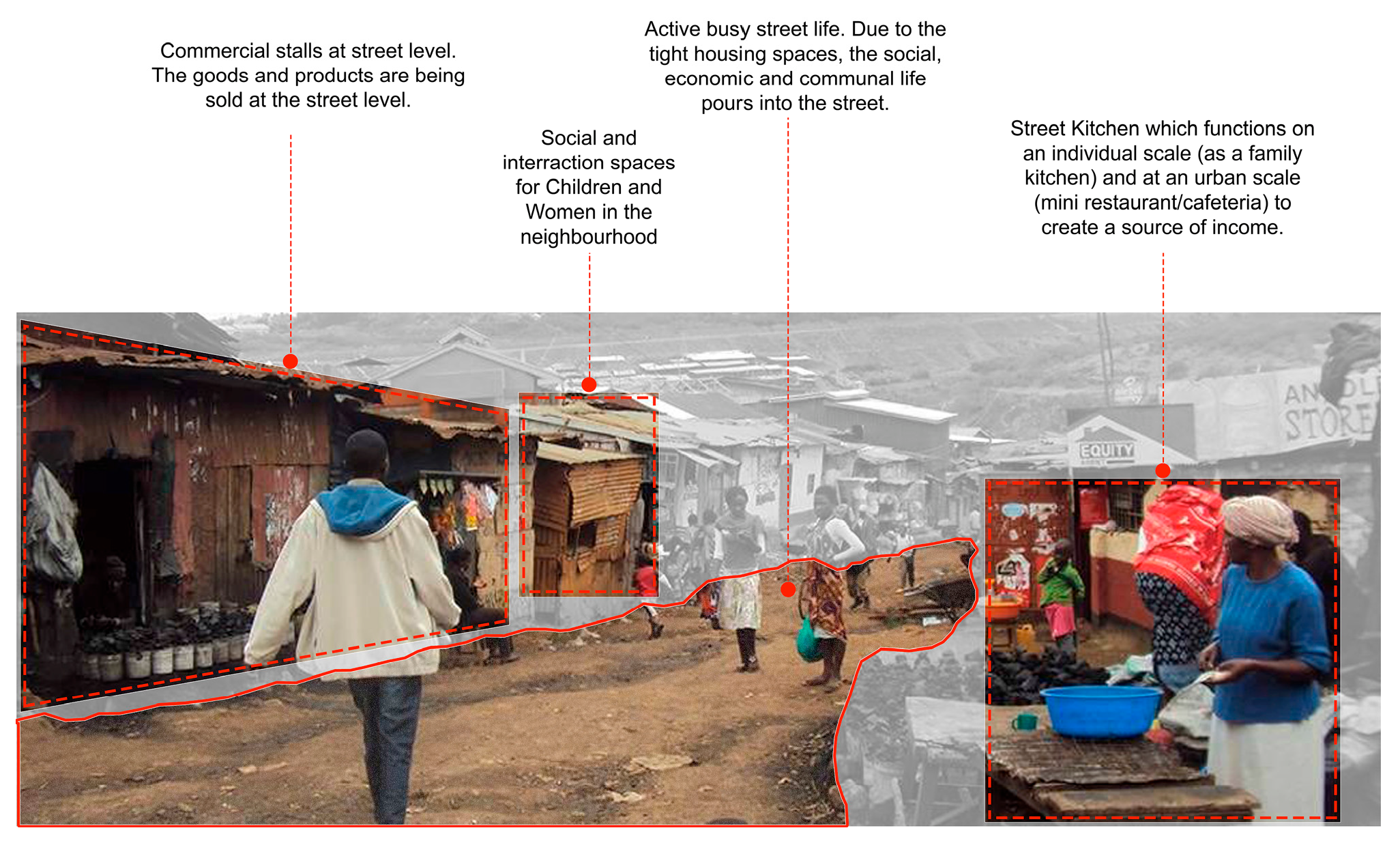

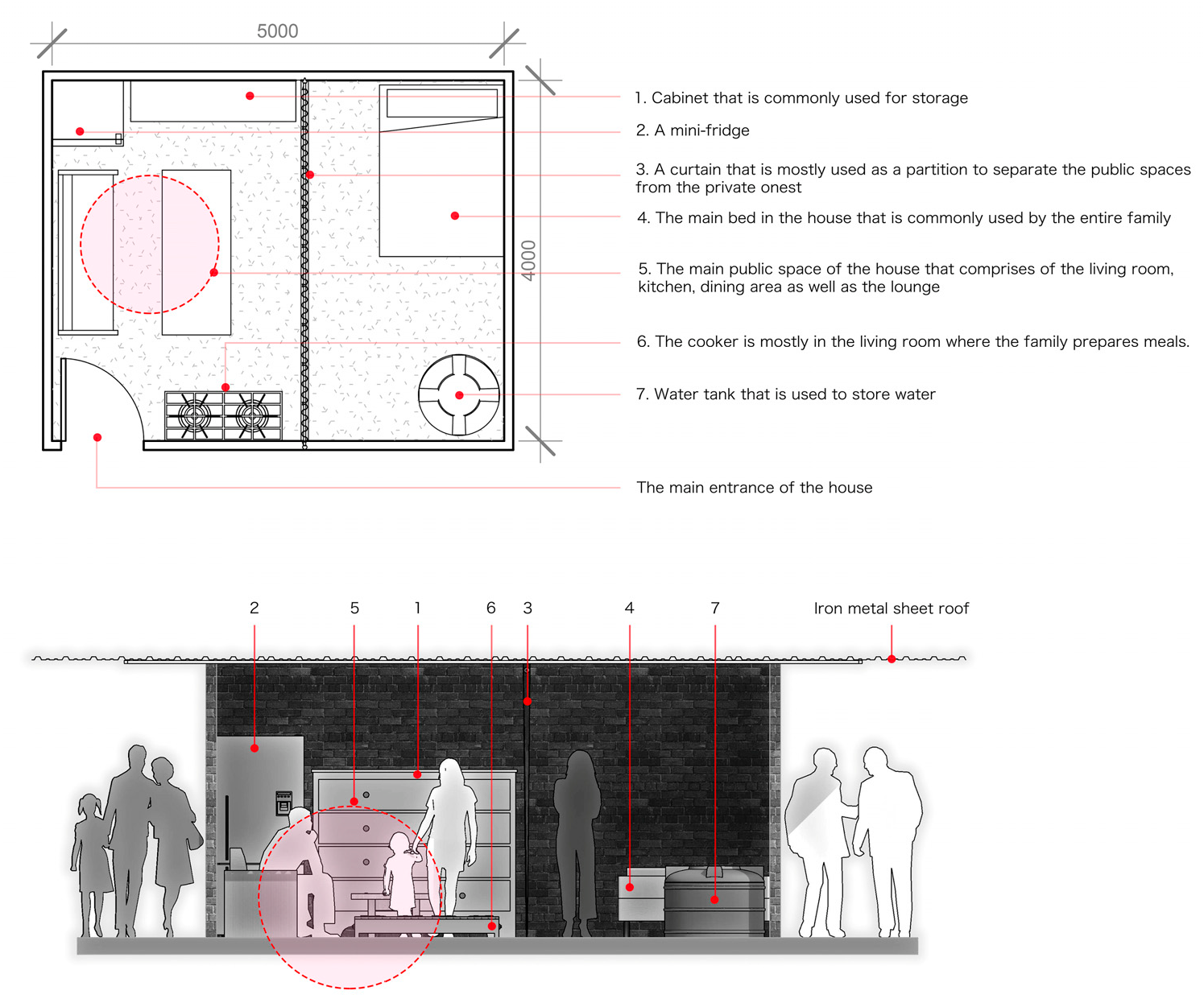

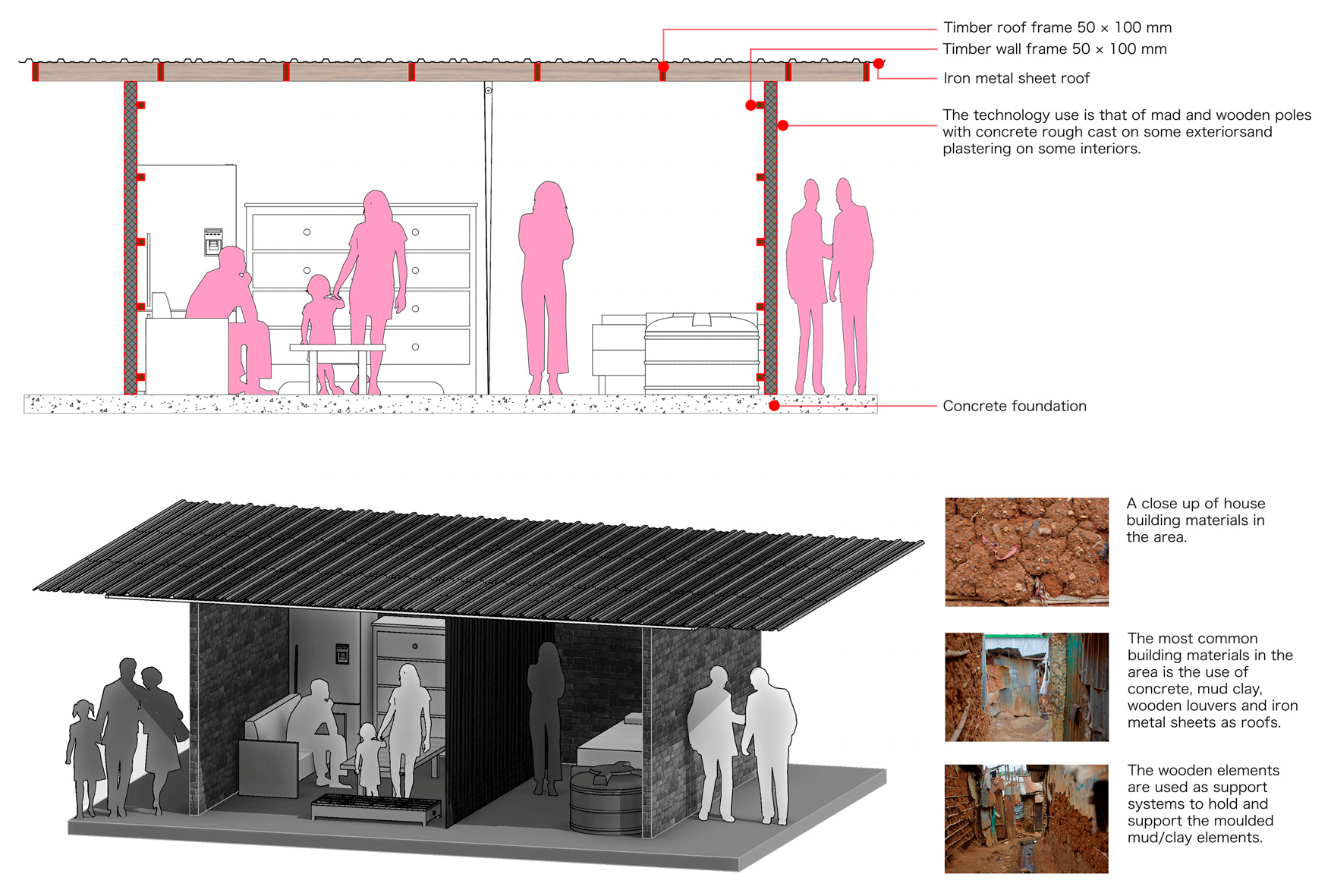

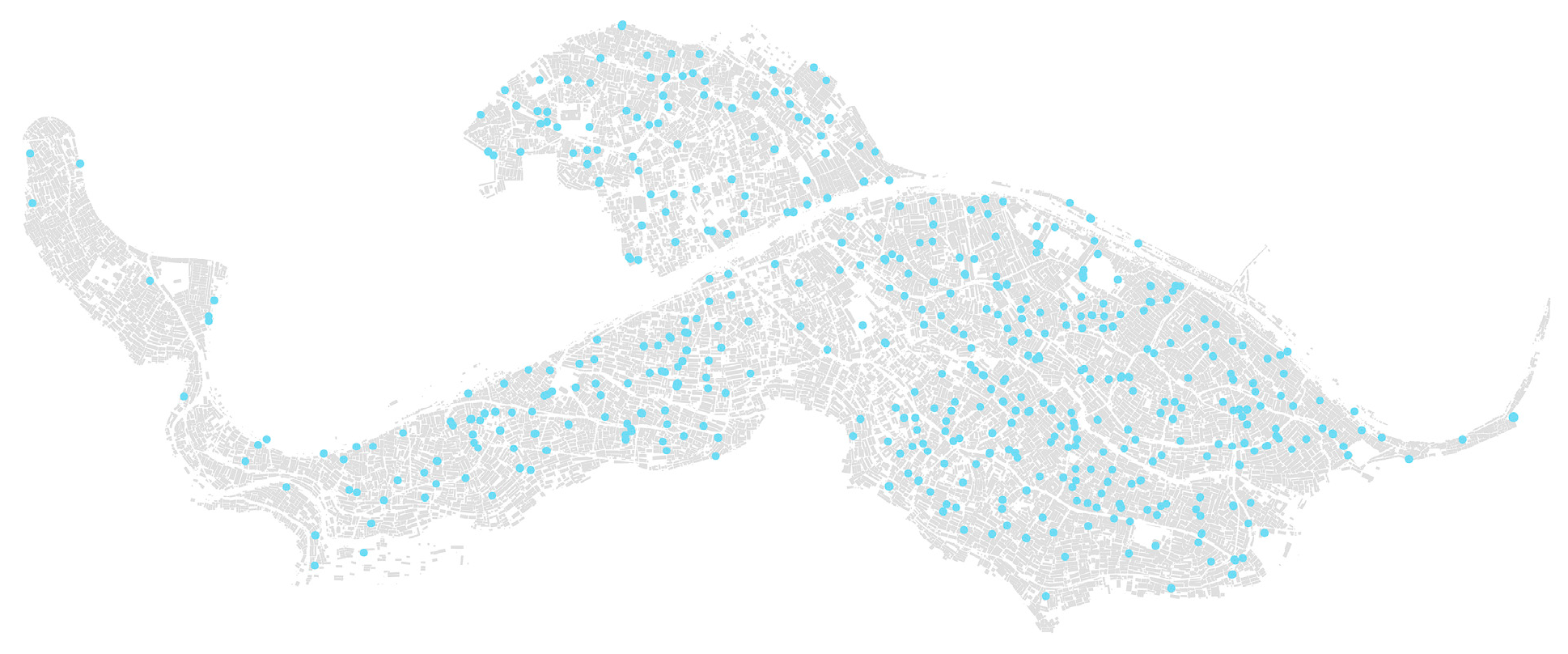

- Mapping technique: young architects are encouraged to utilize mapping techniques and produce maps that illustrate the location and the type of social behavior on the site. They are encouraged to produce maps and identify the location of public places, existing building typologies and land use. They are expected to record the location of the existing routes, distances, and major natural features by using mapping techniques. Social mapping—as part of mapping the community—involves conversing with local people to discover important locations, such as public places as meeting places, places of production, such as workshops or home-workshops, and how slum dwellers relate to the aforementioned places [116]. The young architects are required to use maps, aerial photographs, and application such as Google Earth, which are accessible to them. Maps as an effective tool can assist the young architect in comprehending the existing dynamics and complex social and physical layers of the city [121,122]. By comparing aerial photographs taken on various dates, the evolution and development of the slums can be studied;

- (5)

- Sketching on-site: the young architects must carry sketchbooks during the fieldwork and produce sketches on-site. This research regards sketching on-site as a distinct way of knowing the world. By drawing on location, the observer utilizes direct observation. While sketching on-site, a narrative starts to form, which is context-based. The drawing as an instrument can record the environment; it is informational, and explains the inherent complexity in the observed phenomena [123]. Drawing should not be solely regarded as an instrument for documenting the existing condition but as a creative tool that facilitates interactions with individuals, built environments, and landscapes [123,124]. The principal objective of producing drawings on-site can be summarized as following: (a) Drawing as a way to observe, register and comprehend the environment curiously; (b) Drawing as a means to focus on the slow and careful observation of the environment and people; (c) Drawing as a means to facilitate the young architect with context immersion [123,125];

- (6)

- Visual documentation: photography can be regarded as a method of displaying visual data. Similar to drawing on-site, photography is also context-based. Photography is an effective tool for documenting individuals, places, landscapes, and events. It can visualize contextual complexities difficult to explain via narrative text [122]. In some cases, photographs were used to produce drawings, such as drawing by observing a photo or drawing on a photo; the aforementioned methods are effective tools for visualizing data [123]. In addition to the aforementioned methods, collages are made by mixing drawings and photographs. Aerial photographs, visual documentation, sketching, and mapping are low-cost instruments that enable detailed mapping in situ [126].

4.2. Graduation Project (ARC 402) Design Studio

5. Results

6. Research Findings

The Novelty of the Proposed Framework

7. Conclusions

Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/publications/files/wpp2019_highlights.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN. World Population Prospects the 2012 Revision: Highlights and Advance Tables; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/publications/Files/WPP2012_HIGHLIGHTS.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN. World Population to 2300; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Jan/un_2002_world_population_to_2300.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN. World Urbanization Prospects:The 2014 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/publications/files/wup2014-report.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/apps/njlite/ar5wg2/njlite_download2.php?id=10148 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN-Habitat. Global State of Metropolis 2020—Population Data Booklet; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/09/gsm-population-data-booklet-2020_3.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Ooi, G.L.; Phua, K.H. Urbanization and slum formation. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2007, 84, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. A Practical Guide to Designing, Planning and Implementing Citywide Slum Upgrading Programs; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/11/unhabitat_a_practicalguidetodesigningplaningandexecutingcitywideslum.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Buhaug, H.; Urdal, H. An urbanization bomb? Population growth and social disorder in cities. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafahomi, R.; Nadi, R. The transformative characteristics of public spaces in unplanned settlements. A|Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2021, 18, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Urban informality, toward an epistemology of planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSayyad, N. Urban informality as a new way of life. In Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia; Roy, A., AlSayyad, N., Eds.; Lexington Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Simone, A. For the City Yet to Come: Changing Urban Life in Four African Cities; Duke University Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield, S. Negotiating society and identity in urban spaces in the south. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South; Parnell, S., Oldfield, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 339–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sideris, L.A.; Banerjee, T. Postmodern urban form. In Urban Design Reader; Tiesdell, M.C., Ed.; Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.G. Cities without slums’? Global architectures of power and the African city. In African Perspectives 2009; University of Pretoria: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009; pp. 1–13. Available online: https://www.up.ac.za/media/shared/Legacy/sitefiles/file/44/1068/3229/9086/africanperspectives/pdf/papers/gruffydjones.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN-Habitat. Slum Upgrading Legal Assessment Tool; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/slum-upgrading-legal-assessment-tool#:~:text=The%20Slum%20Upgrading%20Legal%20Assessment,in%20force%20in%20a%20country (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN-Habitat. Prosperity for All: Enhancing the Informal Economy Through Participatory Slum Upgrading; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/prosperity-for-all-enhancing-the-informal-economy-through-participatory-slum-upgrading-0 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN-Habitat. Slum Almanac 2015–2016: Tracking Improvement in the Lives of Slum Dwellers; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/slum-almanac-2015-2016-0 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN-Habitat. State of the World’s Cities Report 2006/7; Earthscan: London, UK, 2006; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/state-of-the-worlds-cities-20062007 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Grover, R.; Emmitt, S.; Copping, A. Critical learning for sustainable architecture: Opportunities for design studio pedagogy. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combrinck, C. Socially responsive research-based design in an architecture studio. Front. Archit. Res. 2018, 7, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H.A. Series introduction: Cultural politics and architectural education: Refiguring the boundaries of political and pedagogical practice. In Voices in Architectural Education: Cultural Politics and Pedagogy; Dutton, T.A., Ed.; Bergin & Garvey: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A.M.; Wilkinson, N. Introduction: Legacies for the future of design studio pedagogy. In Design Studio Pedagogy: Horizons for the Future; Salama, A.M., Wilkinson, N., Eds.; The Urban International Press: Gateshead, UK, 2007; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, C.B.; Cennamo, K.; Douglas, S.; Vernon, M.; McGrath, M.; Reimer, Y. A theoretical framework for the studio as a learning environment. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2013, 23, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasin, B. Rethinking the design studio-centered architectural education. A case study at schools of architecture in Turkey. Des. J.: Int. J. All Asp. Des. 2017, 20, S1270–S1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, A.; Gamman, L. Design with society: Why socially responsive design is good enough. CoDesign 2011, 7, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashier, F. Reflections on architectural design education: The return of rationalism in the Studio. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.Z.; Vandevyvere, H.; Allacker, K. Design for the ecological age: Rethinking the role of sustainability in architectural education. J. Archit. Educ. 2013, 67, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J. Introducing sustainability into the architecture curriculum in the United States. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2003, 4, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomonte, S. Handle with care. The challenges of sustainability and the agenda of architectural education. In Teaching a New Environmental Culture, 1st ed.; Voyatzaki, M., Ed.; EAAE Transactions on Architectural Education: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Altomonte, S.; Rutherford, P.; Wilson, R. Mapping the way forward: Education for sustainability in architecture and urban design. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçyeter, B. The place of sustainability in architectural education: Discussion and suggestions. Athens J. Archit. 2016, 2, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, S.; Soygeniş, M.D. A design studio experience: Impacts of social sustainability. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A. Transformative Pedagogy in Architecture & Urbanism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ferro, C.S.; Arredondo, I.A.; Rodriguez, C.M.; Nadal, D.H. Active learning in architectural education: A participatory design experience (PDE) in Colombia. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2019, 39, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guney, Y.I.; Lerner, I. Technology and architectural education: A conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the ICONARCH-I Architecture and Technology International Congress, Konya, Turkey, 15–17 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, A. Educating around architecture. Stud. High. Educ. 1980, 5, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunok, N. Discovering new potentials of Bauhaus-invented: “Vorkurs”. In Proceedings of the Architectural Episodes 02: New Dialogues in Architectural Education and Practice, İstanbul, Turkey, 24–25 March 2022; pp. 294–308. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo, J. Critical reasoning for an enlightened architectural practice. J. Archit. Educ. 1988, 41, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvan, T.; Yunyan, J. Students’ learning styles and their correlation with performance in architectural design studio. Des. Stud. 2005, 26, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, D.; Pilling, S. Changing Architectural Education: Towards a New Professionalism; Spon Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Boyer, M.E. Adapted verbal feedback, instructor interaction and student emotions in the landscape architecture studio. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2015, 34, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanin, A. Cultural diversity and reforming social behavior: A participatory design approach to design pedagogy. Int. J. Archit. Res. ArchNet-IJAR 2013, 7, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, N.P. Aesthetics, Ideology, and The “Slum”. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Reinventing Design Pedagogy and Contextual Aesthetics, Calicut, India, 30–31 January 2015; National Institute of Technology: Calicut, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, R.S.; Shabitha, P.; Radhakrishnan, S. Collaborative and participatory design approach in architectural design studios. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2020, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J. Differences matter: Learning to design in partnership with others. In Service-Learning in Design and Planning: Educating at the Boundaries; Agnotti, T., Doble, C., Horrigan, P., Eds.; New Village Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hester, R.T. Landstyles and lifescapes: 12 Steps to community development. Landsc. Archit. 1985, 75, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- McNally, M.J. Nature big and small: Landscape planning in the wilds of Los Angeles. Landsc. J. 2011, 30, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.J. Going out into the field: An experience of the landscape architecture studio incorporating service-learning and participatory design in Taiwan. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, E.A. The history of sustainability the origins and effects of a popular concept. In Sustainability in Tourism: A Multidisciplinary Approach; Jenkins, I., Schröder, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Sustainability. Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Molinario, E.; Bonaiuto, F.; Bonnes, M.; Cicero, L.; De Dominicis, S.; Bonaiuto, M. What makes you a “hero” for nature? Socio-psychological profiling of leaders committed to nature and biodiversity protection across seven; EU countries. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 970–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, E.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Knight, A.T.; Ling, M.A.; Darrah, S.; Soesbergen, A.; Burgess, N.D. Status and trends in global ecosystem services and natural capital: Assessing progress toward Aichi Biodiversity Target 14. Conserv. Lett. 2016, 9, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J. Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Pisani, J.A. Sustainable development—Historical roots of the concept. Environ. Sci. 2006, 3, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, A.H.; Kumarasuriyar, A. The social dimension of sustainability: Towards some definitions and analysis. J. Soc. Sci. Policy Implic. 2016, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R. The Silent Spring; Houghton Mifflin Company: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, E. A Blueprint for Survival; Houghton Mifflin: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Tulloch, L. On science, ecology and environmentalism. Policy Futur. Educ. 2013, 11, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, L.; Neilson, D. The neoliberalisation of sustainability. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2014, 13, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Available online: https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/media/publications/sustainable-development/brundtland-report.html (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Schaefer, A.; Crane, A. Addressing sustainability and consumption. J. Macromarketing 2005, 25, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, M. A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustain.: Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, M. Strengthening the “social” in sustainable development: Developing a conceptual framework for social sustainability in a rapid urban growth region in Australia. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Mieg, H.A.; Frischknecht, P. Principal sustainability components: Empirical analysis of synergies between the three pillars of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griessler, E.; Littig, B. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 65–79. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-5491 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Hancock, T. Health, human development and the community ecosystem: Three ecological models. Health Promot. Int. 1993, 8, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. Critical reflections on the theory and practice of social sustainability in the built environment-a meta-analysis. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1526–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. Social sustainability discourse: A critical revisit. In Urban Social Sustainability: Theory, Policy and Practice; Shirazi, M.R., Keivani, R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Magis, K.; Shinn, C. Emergent principles of social sustainability. In Understanding the Social Dimension of Sustainability; Dillard, J., Dujon, V., King, M.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcraft, S. Social sustainability and new communities: Moving from concept to practice in the UK. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J. Toward a “just” sustainability? Contin. J. Media Cult. Stud. 2008, 22, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Lee, S. Neighborhood built environments affecting social capital and social sustainability in Seoul, Korea. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.S.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Antons, D.C.; Munoz, P.; Bai, X.; Fragkias, M.; Gutscher, H. A vision for human well-being: Transition to social sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.G.; Kogevinas, M.; Elston, M.A. Social/economic status and disease. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1987, 8, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, P.M.; Golberstein, E.; House, J.S.; Morenoff, J. Socioeconomic and behavioral risk factors for mortality in a national 19-year prospective study of US adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besancon, M.L. Relative resources: Inequality in ethnic wars, revolutions, and genocides. J. Peace Res. 2005, 42, 393–415. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30042333 (accessed on 1 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C. Does inequality cause conflict? J. Int. Dev. 2003, 15, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger; Bloomsbury Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, G.; Dubourg, R.; Hamilton, K.; Munasinghe, M.; Pearce, D.; Young, C. Measuring Sustainable Development: Macroeconomics and the Environment, 1st ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Programme on Mental Health: WHOQOL User Manual; World Health Organization: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77932/WHO_HIS_HSI_Rev.2012.03_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- OECD. OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Quality of Life; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, N. Assessing urban sustainability of slum settlements in Bangladesh: Evidence from Chittagong city. J. Urban Manag. 2018, 7, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyinka, O.; Siu, K.W.M.; Lawanson, T.; Adeniji, O. Assessing smart infrastructure for sustainable urban development in the Lagos metropolis. J. Urban Manag. 2016, 5, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J. Sustainability and cities: Summary and conclusions. In Designing Cities: Critical Readings in Urban Design; Cuthbert, A.R., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Elrayies, G.M. Rethinking Slums: An Approach for Slums Development towards Sustainability. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 9, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Beeck, S.; Lommerse, M.; Metcalfe, P. An introduction to social sustainability and interior architecture. In Perspectives on Social Sustainability and Interior Architecture; Smith, D., Lommerse, M., Metcalfe, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A. School green space and its impact on academic performance: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, J.; Damschroder, L. Qualitative Content Analysis. Empir. Methods Bioeth. A Primer 2008, 11, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S. Focus group research. In Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practic; Silverman, D., Ed.; Sage Publication: London, UK, 2004; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, E. Focus groups. In Qualitative Research in Health Care; Bassett, C., Ed.; Whurr Publishers: London, UK, 2004; pp. 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M.; Atkinson, P. Ethnography: Principles in Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, J. Ethnography: Principles, practice and potential. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, M. Introducing ethnography. In Researching Language and Literacy in Social Context: A Reader; Graddol, D., Maybin, J., Stierer, B., Eds.; The Open University: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, P.; Coffet, A.; Delamont, S.; Lofland, J.; Lofland, L. Handbook of Ethnography; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, G.S. An introduction to the origins, history and principles of ethnography. Nurse Res. 2017, 24, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luders, C. Field observation and ethnography. In A Companion to Qualitative Research; Flick, U., Kardorff, E.V., Steinke, I., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, E.V.; Higginbottom, G. The use of focused ethnography in nursing research. Nurse Res. 2013, 20, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R.; DeVault, M.L. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. Research by design: Proposition for a methodological approach. Urban Sci. 2017, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, F. Urban design and informal settlements: Placemaking activities and temporary architectural interventions in BaSECo compound. Urban Des. Int. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rains, E.; Krishna, A.; Wibbels, E. Combining satellite and survey data to study Indian slums: Evidence on the range of conditions and implications for urban policy. Environ. Urban. 2018, 31, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalipour, H. Improvising places: The fluidity of space in informal settlements. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K. Informalising architecture: The challenge of informal settlements. AD Archit. Des. 2013, 83, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.M. A theory for integrating knowledge in architectural design education. ArchNet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2008, 2, 100–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.M. Learning from the environment: Evaluation research and experience based architectural pedagogy. Cent. Educ. Built Environ. Trans. 2006, 3, 64–83. Available online: https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/50239/ (accessed on 1 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Schensul, J.J.; Lecompte, M.D. Specialized Ethnographic Methods: A Mixed Methods Approach; AltaMira Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Angrosino, M. Doing Ethnographic and Observational Research, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Levina, N.; Vaast, E. The emergence of boundary spanning competence in practice: Implications for implementation and use of information systems. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 335–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.C.; Clarke, N.J. Red in Architecture: An Ecotropic Approach; University of Pretoria Department of Architecture: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011; Available online: https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/19602?show=full (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Lee, J.; Ingold, T. Fieldwork on foot: Perceiving, routing, socializing. In Locating the Field: Space, Place and Context in Anthropology; Coleman, S., Collins, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, A. Making sense of cities: The role of maps in the past, present, and future of urban planning. In Mapping Across Academia; Brunn, S.D., Dodge, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, K. Viewing places: Students as visual ethnographers. Art Educ. 2010, 63, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschnir, K. Ethnographic drawing: Eleven benefits of using a sketchbook for fieldwork. Vis. Ethnogr. 2016, 5, 103–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.J. Drawing the lines: The limitations of intercultural ekphrasis. In Working Images: Visual Research and Representation in Ethnography; Pink, S., Kürti, L., Afonso, A.I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Causey, A. Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paar, P.; Rekittke, J. Low-cost mapping and publishing methods for landscape architectural analysis and design in slum-upgrading projects. Future Internet 2011, 3, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, K. Key Concepts in Ethnography; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, S. Fieldwork as commitment. Geogr. Rev. 2001, 91, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.M.; Gray, N.J.; Meletis, Z.A.; Abbott, J.G.; Silve, J.J. Gatekeepers and keymasters: Dynamic relationships of access in geographical fieldwork. Geogr. Rev. 2006, 96, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, L. Just doing it: The role of experiential learning and integrated curricula in architectural education. Int. J. Pedagog. Curric. 2014, 20, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cities Alliance. Cities Without Slums: Action Plan for Moving Slum Upgrading to Scale; World Bank/UNCHS (Habitat): Washington, DC, USA, 1999; Available online: https://www.citiesalliance.org/cities-without-slums-action-plan (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UNICEF. Pneumonia and Diarrhoea: Tackling the Deadliest Diseases for the World’s Poorest Children; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/pneumonia-and-diarrhoea-tackling-the-deadliest-diseases-for-the-worlds-poorest-children/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Hutton, G.; Haller, L. Evaluation of the Costs and Benefits of Water and Sanitation Improvements at the Global Level; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/68568 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Devkar, G.; Rajan, A.T.; Narayanan, S.; Elayaraja, M.S. Provision of basic services in slums: A review of the evidence on top-down and bottom-up approaches. Dev. Policy Rev. 2017, 37, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, T.R.; Devkar, G.; Mahalingam, A.; Benjamin, S.; Rajan, S.C.; Deep, A. What Is the Evidence on Top-Down and bottom-Up Approaches in Improving Access to Water, Sanitation and Electricity Services in Low-Income or Informal Settlements? EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2016; Available online: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Publications/Systematicreviews/Sanitationservices/tabid/3682/Default.aspx (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- WaterAid. Tiruchirappalli Shows the Way: Community-Municipal Corporation-NGO Partnership for City-Wide Pro-Poor Slums’ Infrastructure Improvement; WaterAid: New Delhi, India, 2008; Available online: https://www.ircwash.org/resources/tiruchirappalli-shows-way-community-municipal-corporation-ngo-partnership-city-wide-pro (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Weitz, A.; Franceys, R. Beyond Boundaries: Extending Services to the Urban Poor; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2008; Available online: https://gsdrc.org/document-library/beyond-boundaries-extending-services-to-the-urban-poor/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Kifanyi, G.E.; Shayo, B.M.B.; Ndambuki, J.M. Performance of community based organizations in managing sustainable urban water supply and sanitation projects. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2013, 8, 1558–1569. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/69249850/Performance_of_community_based_organizations_in_managing_sustainable_urban_water_supply_and_sanitation_projects (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- UN-Habitat. Community Land Trusts: Affordable Access to Land and Housing; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/community-land-trusts-affordable-access-to-land-and-housing (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Syagga, P. Land Tenure in Slum Upgrading Projects; French Institute for Research in Africa: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011; pp. 103–113. Available online: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00751866 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Midheme, E.; Moulaert, F. Pushing back the frontiers of property: Community land trusts and low-income housing in urban Kenya. Land Use Policy 2013, 35, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usoro, U. Effectiveness of Sites and Services Schemes in Low and Medium Income Housing Provision in Nigeria. Int. J. Econ. Dev. Res. Invest. 2015, 6, 39–50. Available online: https://www.icidr.org/ijedri-vol6-no2-august2015/Effectiveness%20of%20Site%20and%20Services%20Schemes%20in%20Low%20and%20Medium%20Income%20Housing.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Bah, E.M.; Faye, I.; Geh, Z.F. Slum Upgrading and Housing Alternatives for the Poor. In Housing Market Dynamics in Africa, 1st ed.; Bah, E.M., Faye, I., Geh, Z.F., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 215–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.; Rojas, E. Incremental construction: A strategy to facilitate access to housing. Environ. Urban. 2008, 20, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, P. Small is beautiful, but big is often the practice: Housing microfinance in discussion. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lim, Y.; Kim, K.; Wang, H. Revisit to incremental housing focusing on the role of a comprehensive community centre: The case of Jinja, Uganda. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2018, 23, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Financing Urban Shelter: Global Report on Human Settlements; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/financing-urban-shelter-global-report-on-human-settlements (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Amoako, C.; Boamah, E.F. Build as you earn and learn: Informal urbanism and incremental housing financing in Kumasi, Ghana. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2017, 32, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorloos, F.V.; Cirolia, L.R.; Friendly, A.; Jukur, S.; Schramm, S.; Steel, G.; Valenzuela, L. Incremental housing as a node for intersecting flows of city-making: Rethinking the housing shortage in the global south. Environ. Urban. 2019, 32, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, K.E.; Gulyani, S.; Rizvi, A. Success when deemed it failure? Revisiting sites and services projects in Mumbai and Chennai 20 years later. World Dev. 2018, 106, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handzic, K. Is legalized land tenure necessary in slum upgrading? Learning from Rio’s land tenure policies in the Favela Bairro programme. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D.; Quigley, J.M. The consumption benefits of investment in infrastructure: The evaluation of sites-and-services programs in underdeveloped countries. J. Dev. Econ. 1987, 25, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, L.R. Some second thoughts on sites-and-services. Habitat Int. 1982, 6, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.F.C. Housing in three dimensions: Terms of reference for the housing question redefined. World Dev. 1978, 6, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.F.C. From central provision to local enablement: New directions for housing policies. Habitat Int. 1983, 7, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.H.; Feng, Y. 12 years after: Lessons from incremental changes in open spaces in a slum-upgrading project. Landsc. Res. 2019, 45, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayitno, B. Co-habitation space: A model for urban informal settlement consolidation for the heritage city of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2017, 16, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alja’afreh, A.; Al Tal, R.; Ibrahim, A. The social role of open spaces in informal settlements in Jordan. Open House Int. 2022, 47, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, J. Public Spaces in Informal Settlements; Cambridge Scholar Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Worpole, K.; Knox, K. The Social Value of Public Spaces; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Why are the design and development of public spaces significant for cities? Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 1999, 26, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Chinyimba, A.; Hebinck, P.; Shackleton, C.; Kaoma, H. Multiple benefits and values of trees in urban landscapes in two towns in northern South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Choi, M.J.; Ko, J. Quantitative and qualitative demand for slum and non-slum housing in Delhi: Empirical evidences from household data. Habitat Int. 2013, 38, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthia, S.A. Analysis of urban slum: Case study of Korail Slum, Dhaka. Int. J. Urban Civ. Eng. 2020, 14, 416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, N.; Reynolds, K.; Sanghvi, R. Five Borough Farm: Seeding the Future of Urban Agriculture in New York City; Design Trust for Public Space: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, S. Urban poor, economic opportunities and sustainable development through traditional knowledge and practices. Glob. Bioeth. 2015, 26, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, K.; Conard, M.; Culligan, P.; Plunz, R.; Sutto, M.P.; Whittinghill, L. Sustainable food systems for future cities: The potential of urban agriculture. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2014, 45, 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Specht, K.; Siebert, R.; Hartmann, I.; Freisinger, U.B.; Sawicka, M.; Werner, A.; Thomaier, S.; Henckel, D.; Walk, H.; Dierich, A. Urban agriculture of the future: An overview of sustainability aspects of food production in and on buildings. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 31, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zezza, A.; Tasciotti, L. Urban agriculture, poverty, and food security: Empirical evidence from a sample of developing countries. Food Policy 2010, 35, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenbrod, C.; Gruda, N. Urban vegetable for food security in cities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enete, A.A.; Achike, A.I. Urban agriculture and urban food insecurity/poverty in Nigeria: The case of Ohafia, South-East Nigeria. Outlook Agric. 2008, 37, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Growing Greener Cities in Latin America and the Caribbean; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/es/c/4b8afd1d-e530-4825-b32d-4f088e5b62ae/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Renard, N. Introduction. In Urban Agriculture: Another Way to Feed Cities; Martin-Moreau, M., Ménascé, D., Eds.; Veolia Institute: Aubervilliers, France, 2019; p. 3. Available online: https://www.institut.veolia.org/en/nos-contenus/la-revue-de-linstitut-facts-reports/urban-agriculture-another-way-feed-cities (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Rogerson, C.M. Feeding Africa’s Cities: The Role and Potential for Urban Agriculture. Afr. Insight 1992, 22, 229–234. Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA02562804_516 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Martin-Moreau, M.; Menascé, D. New agricultural purposes in the city. In Urban Agriculture: Another Way to Feed Cities; Martin-Moreau, M., Ménascé, D., Eds.; Veolia Institute: Aubervilliers, France, 2019; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Antolihao, L.; Van Horen, B. Building institutional capacity for the upgrading of Barangay Commonwealth in Metro Manila. Hous. Stud. 2005, 20, 873–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, D.; Nagendra, H. Vegetation in Bangalore’s slums: Boosting livelihoods, well-being and social capital. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2459–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.; Webber, M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, H. Design as research: Creative works and the design studio as scholarly practice. Archit. Theory Rev. 2009, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Utaberta, N. Learning in architecture design studio. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 60, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, T.A. The hidden curriculum and the design studio. In Voices in Architectural Education: Cultural Politics and Pedagogy; Dutton, T.A., Ed.; Bergin & Garvey: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 165–194. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, K.H. Design Juries on Trial: The Renaissance of the Design Studio; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cuff, D. Architecture: The Story of Practice; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McClean, D. Embedding Learner Independence in Architecture Education: Reconsidering Design Studio Pedagogy. Doctoral Dissertation, The Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland, 1 May 2009. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10059/1253 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Hoadley, C.; Cox, C. What is design knowledge and how do we teach it? In Educating Learning Technology Designers: Guiding and Inspiring Creators of Innovative Educational Tools; DiGiano, C., Goldman, S., Chorost, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Barab, S.A.; Duffy, T.M. From practice fields to communities of practice. In Theoretical Foundations of Learning Environments, 2nd ed.; Johassen, D.H., Land, S.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, N.A.G.; Beh, S.C.; Tahir, M.M.; Che Ani, A.I.; Tawil, N.M. Architecture design studio culture and learning spaces: A holistic approach to the design and planning of learning facilities. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetzer, E. Knowledge Building in Landscape Architecture; Kassel University Press: Kassel, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Lubart, T.I. The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In Handbook of Creativity; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. A new paradigm for design studio education. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2010, 29, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocato, K. Studio based learning: Proposing, critiquing, iterating our way to person-centeredness for better classroom management. Theory Into Pract. 2009, 48, 138–146. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40344604 (accessed on 1 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Design Studio: An Exploration of Its Traditions and Potentials; RIBA: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, K.; Sutton, R. Educational Psychology; The Global Text Project: Zurich, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Woolfolk, A. Educational Psychology; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

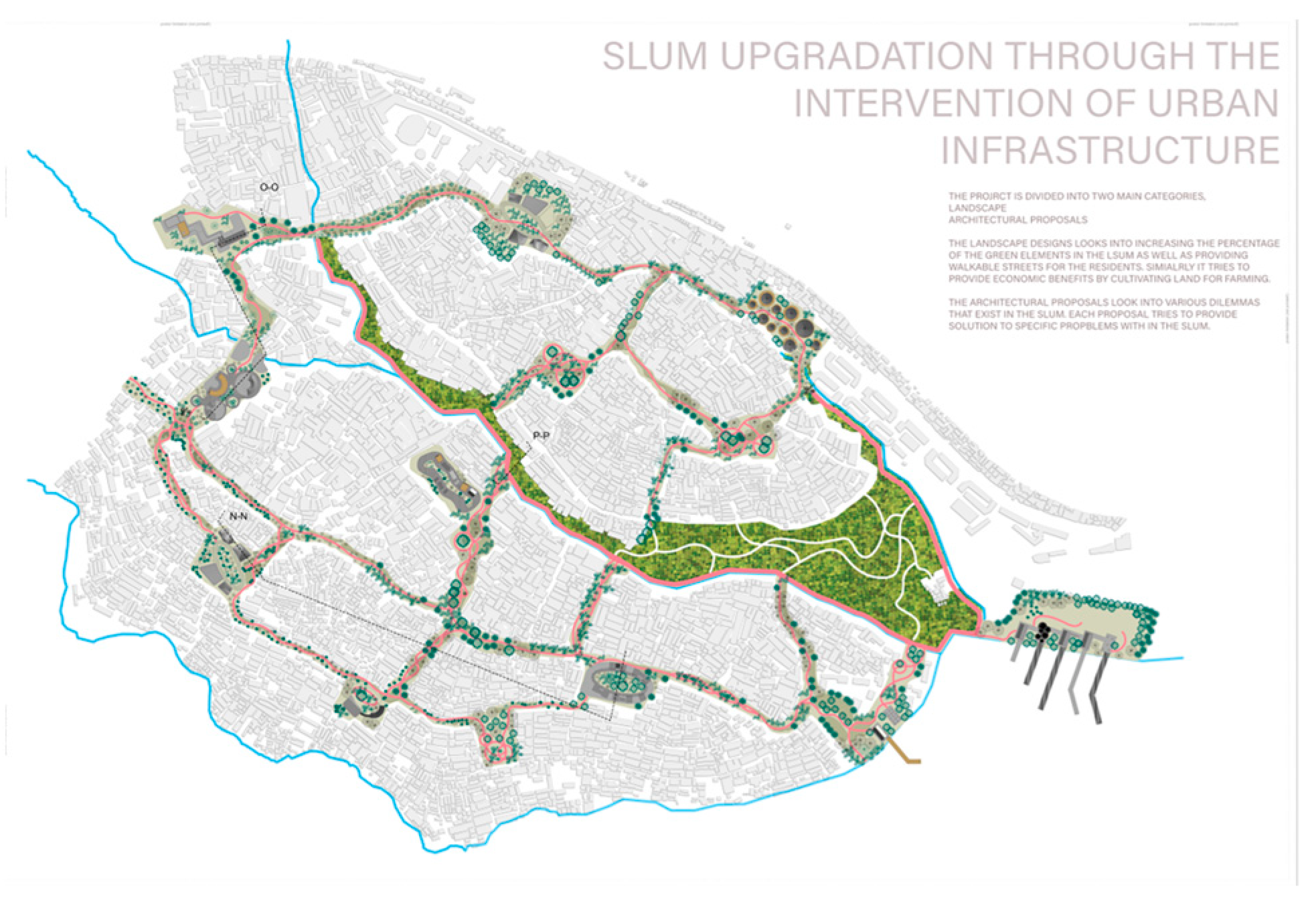

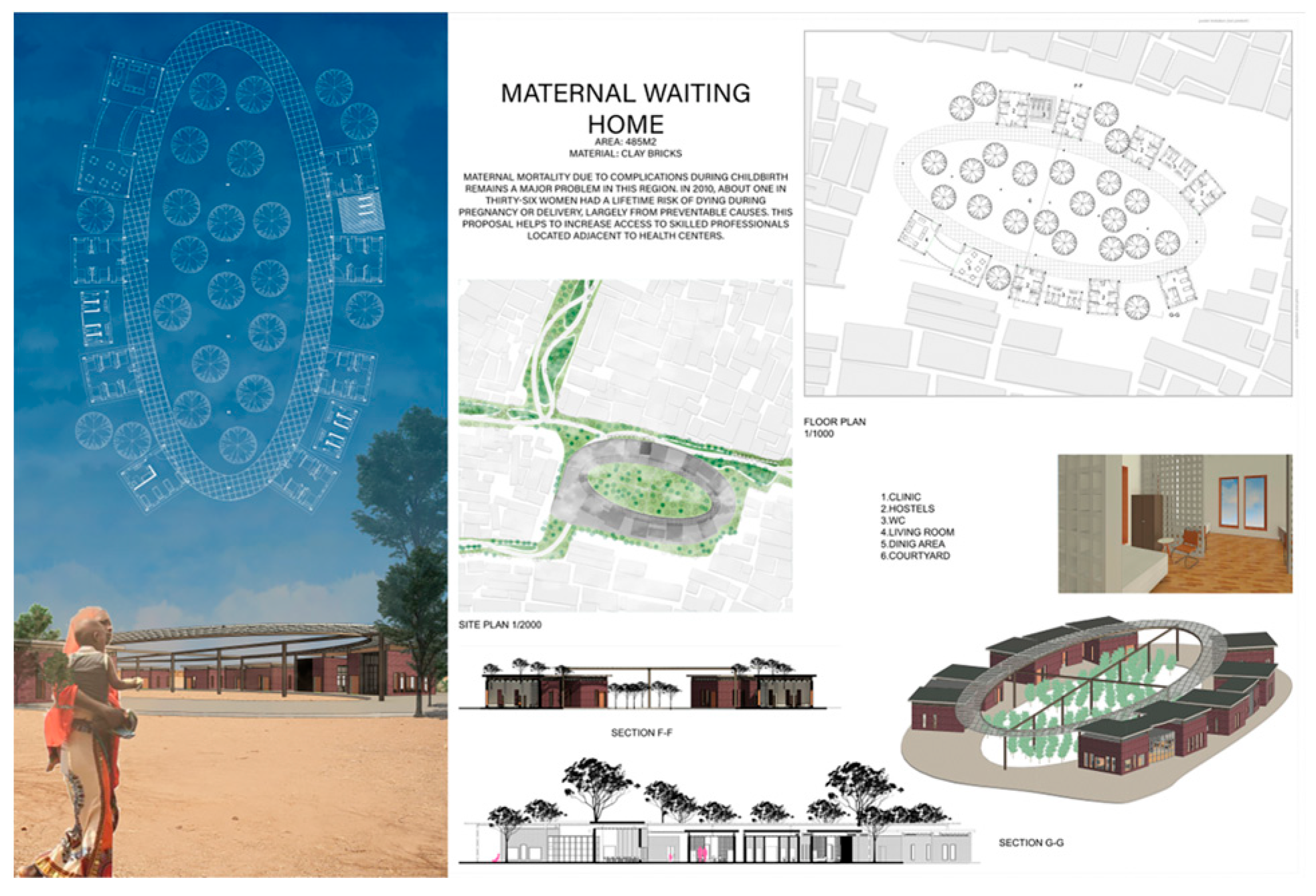

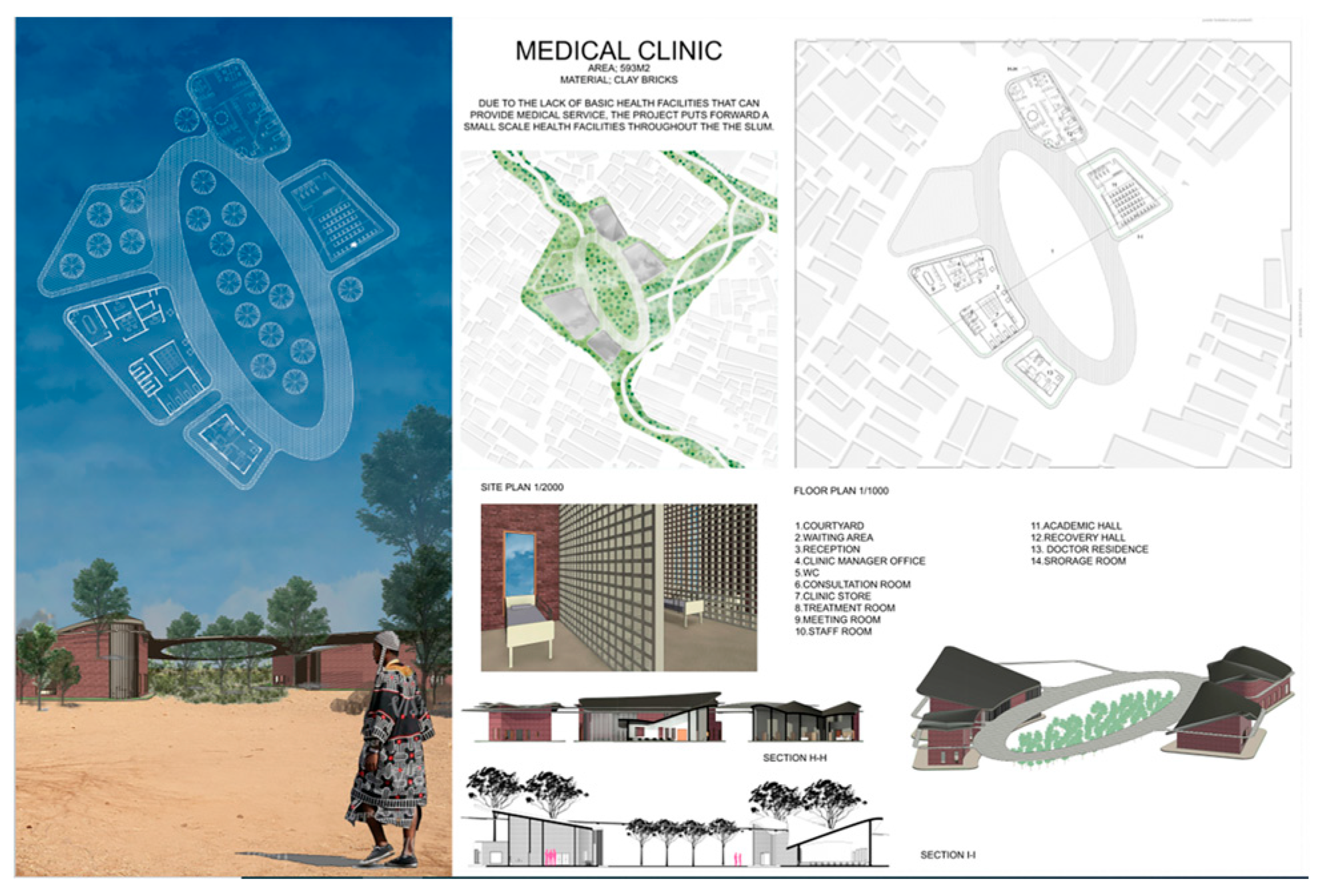

- Sheikh Ahmed, A.D. Slum Upgrade through the Intervention of Urban Infrastructure. Bachelor’s Thesis, Department of Interior Design, Faculty of Architecture, Design & Fine Arts, Girne American University, Girne, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Phase One |

|---|

| Conducting fieldwork and utilizing the following data collection tools: (1) Participant observation; (2) Informal interviewing; (3) Walking and observing the site; (4) Mapping technique; (5) Sketching on-site; (6) Visual documentation. |

| Phase One outcomes: (1) Gaining in-depth insight regarding the site and its context; (2) Establishing connections with locals; (3) Identifying local solutions; (4) Identifying the site’s potential. |

| Categories | Stakeholders/Required Action | Long-Term Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Category A: Non-land owners | Tenants | Empowered to be legalized structure owners |

| Resident structure owners | Maintain the current structure/incremental horizontal or vertical expansion/legalize the structure | |

| Non-resident structure owners | Maintain the current structure/incremental horizontal or vertical expansion/legalize the structure | |

| Category B: Legalized land-owners | Vacant land-owners/transfer the land title to the Community Land Trust | Build structure/legalize the structure/receive technical assistance from community land trust/become legalized structure owners |

| The land owners with a built structure on it/transfer the land title to community land trust | Maintain or expand the current structure/legalize the structure/receive technical assistance from community land trust/become legalized structure owners | |

| Category C: Non-legalized land-owners | Transfer the land title to community land trust | Built, maintained or expanded the structure/legalized the structure/received technical assistance from community land trust/become legalized structure owners |

| Phase Two |

|---|

| Theoretical discussions during the weekly lectures: (1) Providing basic infrastructure; (2) Tenure legalization; (3) Self-built incremental housing and sites and services; (4) Construction of community facilities; (5) Upgrading open spaces; and (6) Enhancement of income-earning opportunities. |

| Phase Two outcomes: (1) The young architects are familiarized with existing theoretical and practical solutions; and (2) The young architects have engaged in research and present their research findings in their theses. |

| Phase Three |

|---|

| 1. Engage in rigorous research and study, and select relevant case study precedents; 2. Identify innovative design patterns for each selected case study. Design patterns include: (1) Design concepts; (2) Architectural design solutions; and (3) Landscape design solutions. |

| Phase Three outcomes: (1) Building an inventory of design patterns; (2) Presenting their inventory of design patterns in their theses. |

| Phase One | Phase Two | Phase Three | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Contextual theoretical and practical solutions; 2. Contextualized design patterns; 3. Considering social sustainability indicators: social equity, well-being and quality of life. |  Receiving regular feedback. | 1. Making sure theoretical and practical solutions function appropriately; 2. Contextualized design patterns should function accurately; 3. Contextualized design patterns should engage with each other accordingly; 4. Design proposal should enhance the well-being and quality of life of stakeholders and contribute to their social equity. |  Receiving regular feedback. | Final design proposal representation |

| Initial design proposal | Initial final design proposal | Final design |

| Phase One |

|---|

| Conducting fieldwork and utilizing the following data collection tools: (1) Participant observation; (2) Informal interviewing; (3) Walking and observing the site; (4) Mapping technique; (5) Sketching on-site; and (6) Visual documentation. |

| Phase One outcomes: (1) Gaining in-depth insight regarding the site and its context; (2) Establishing connections with locals; (3) Identifying local solutions; (4) Identifying the site’s potential. |

| Phase Two |

| Theoretical discussions during the weekly lectures: (1) Providing basic infrastructure; (2) Tenure legalization; (3) Self-built incremental housing and sites and services; (4) Construction of community facilities; (5) Upgrading open spaces; and (6) Enhancement of income-earning opportunities. |

| Phase Two outcomes: (1) The young architects are familiarized with existing theoretical and practical solutions; and (2) The young architects engage in research and present their research findings in their theses. |

| Phase Three |

| 1. Engaging in rigorous research and study, and selecting relevant case study precedents; 2. Identifying innovative design patterns for each selected case study. Design patterns include: (1) Design concepts; (2) Architectural design solutions; and (3) Landscape design solutions. |

| Phase Three outcomes: (1) Building an inventory of design patterns; (2) Presenting their inventory of design patterns in their theses. |

| Phase One | Phase Two | Phase Three | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Contextual theoretical and practical solutions; 2. Contextualized design patterns; 3. Considering social sustainability indicators: social equity, well-being and quality of life. |  Receiving regular feedback. | 1. Making sure theoretical and practical solutions function appropriately; 2. Contextualized design patterns should function accurately; 3. Contextualized design patterns should engage with each other accordingly; 4. Design proposal should enhance the well-being and quality of life of stakeholders and contribute to their social equity. |  Receiving regular feedback. | Final design proposal representation. |

| Initial design proposal | Initial final design proposal | Final design |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daneshyar, E.; Keynoush, S. Developing Adaptive Curriculum for Slum Upgrade Projects: The Fourth Year Undergraduate Program Experience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4877. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064877

Daneshyar E, Keynoush S. Developing Adaptive Curriculum for Slum Upgrade Projects: The Fourth Year Undergraduate Program Experience. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):4877. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064877

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaneshyar, Ehsan, and Shahin Keynoush. 2023. "Developing Adaptive Curriculum for Slum Upgrade Projects: The Fourth Year Undergraduate Program Experience" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 4877. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064877

APA StyleDaneshyar, E., & Keynoush, S. (2023). Developing Adaptive Curriculum for Slum Upgrade Projects: The Fourth Year Undergraduate Program Experience. Sustainability, 15(6), 4877. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064877