National Quality and Sustainable Development: An Empirical Analysis Based on China’s Provincial Panel Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The System for the Assessment of National Quality

3.2. The Calculation of Sustainable Economic Development

3.2.1. Weighted Residential Consumption, CISEW

3.2.2. Services of Household Labor, GISEW

3.2.3. Services from Durable Consumer Goods, IISEW

3.2.4. Public Expenditure Cost, W

3.2.5. Social Expenditure Cost, D

3.2.6. Environmental Expenditure Cost, E

4. Empirical Analysis and Results

4.1. Factor Score and Classification of National Quality

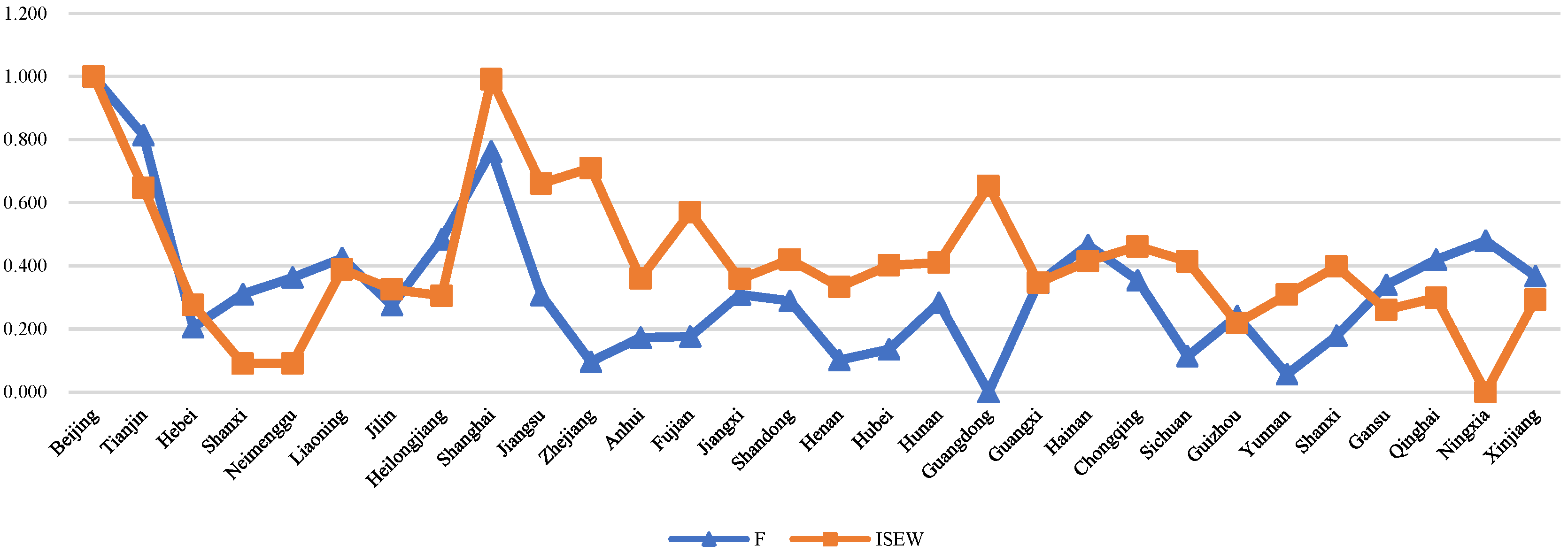

4.2. The Level of Sustainable Economic Development in Each Province

4.3. Analysis of the Correlation between National Quality and Sustainable Economic Development

4.4. Granger Causality Test of National Quality Indexes and Sustainable Economic Development

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X. Interactive Development of Four Forces to Enhance the Influence of Chinese Model-Evaluation and Analysis of China’s International Competitiveness from 2007–2014. Econ. Theory Econ. Manag. 2014, 11, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Evaluation and Analysis of National Economic Quality, 1st ed.; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Research Group of the Competitiveness of National Quality in Chinese Regions; Zhao, Y.; Feng, N.; Zhao, Y. Study on the Competitiveness of National Quality in China. Stat. Res. 2008, 3, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Ji, X. Economic Growth Quality, Environmental Sustainability, and Social Welfare in China-provincial Assessment Based on Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI). Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, P. Discussion on the Law of Adapting National Quality to Economic Growth. J. Henan Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 1998, 25, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, J. National Quality Determines a Country’s Long-term Economic Growth Capacity. Sel. Econ. Pap. Theor. Ed. 2000, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Intellectual and Moral Factors in Economic Growth. Econ. Sci. 2000, 1, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, P. An analysis of the intrinsic relationship between developing productivity and improving national quality. Product. Res. 2012, 7, 88–90+261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J. Core literacy in the 21st century:international perceptions and local reflections. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 3, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H. The international vision and Chinese position of core literacy—The national quality improvement and education goal transformation in 21st century China. Educ. Res. 2016, 37, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Hao, R. Demographic structure and economic growth: Evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2010, 38, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidisha, S.H.; Abdullah, S.M.; Siddiqua, S.; Islam, M.M. How Does Dependency Ratio Affect Economic Growth In the Long Run? Evidence from Selected Asian Countries. J. Dev. Areas 2020, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongyi, L.; Huang, L. Health, education, and economic growth in China: Empirical findings and implications. China Econ. Rev. 2009, 20, 374–387. [Google Scholar]

- Ziberi, B.F.; Rexha, D.; Ibraimi, X.; Avdiaj, B. Empirical analysis of the impact of education on economic growth. Economies 2022, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gylfason, T. Natural resources, education, and economic development. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Jan, C.; Ma, Y.; Dong, B.; Zou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xu, R.; Song, Y.; Ma, J.; Sawyer, S.M.; et al. Economic development and the nutritional status of Chinese school-aged children and adolescents from 1995 to 2014: An analysis of five successive national surveys. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, K. The relationship between traffic accidents and economic growth in China. Econ. Bull. 2010, 30, 3306–3314. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, B.M. The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth; Knopf Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.; Cobb, J. For the common good: Redirecting the economy toward community, the environment, and a sustainable future. J. Econ. Lit. 1989, 29, 593–595. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, C.W.; Cobb, J.B. The Green National Product: A Proposed Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1994; pp. 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, P.; Pan, Y. Does China’s carbon emission trading policy have an employment double dividend and a Porter effect? Energy Policy 2020, 142, 111492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Islam, S.M.N. Diminishing and negative welfare returns of economic growth: An index of sustainable economic welfare (ISEW) for Thailand. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 54, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Fang, X. Revisiting the sustainable economic welfare growth in China: Provincial assessment based on the ISEW. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 162, 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E.; Cobb, C.W. For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future, 2nd ed.; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony, T.; Escardo-Serra, P.; Dufour, J. Revisiting ISEW Valuation Approaches: The Case of Spain Including the Costs of Energy Depletion and of Climate Change. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. Accounting of the value of housework. Stat. Decis. 2018, 34, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. A study on the impact of China’s carbon trading policy on sustainable economic welfare. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pulselli, F.M.; Ciampalini, F.; Tiezzi, E.; Zappia, C. The index of sustainable economic welfare (ISEW) for a local authority: A case study in Italy. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 60, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Tang, K.; Wang, Z.; An, H.; Fang, W. Regional Eco-efficiency and Pollutants Marginal Abatement Costs in China: A Parametric Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleys, B. The Regional Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare for Flanders, Belgium. Sustainability 2013, 5, 496–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. The necessity of data forwarding processing in factor analysis and its software implementation. J. Chongqing Eng. Coll. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2009, 23, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, A.; Zhang, N. Alternative techniques of human development index based on principal component analysis. Econ. Res. 2005, 7, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V.; Dailimi, M.; Dhareshwar, A.; Ramon, E.L.; Daniel, K.; Nalin, K.; Yan, W. The Quality of Growth; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mishan, B. The Costs of Economic Growth, 2nd ed.; F. A. Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Činčikaitė, R.; Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I. An Integrated Assessment of the Competitiveness of a Sustainable City within the Context of the COVID-19 Impact. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. An Empirical Study on the Relationship between National Quality and Economic Growth in China. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W. The importance of national quality in the process of economic growth. China’s Collect. Econ. 2014, 33, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, W.; Wang, B. Economics of Growth; People’s Publishing House: Wuhan, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Belke, M.; Bolat, S. The panel data analysis of female labor participation and economic development relationship in developed and developing countries. In Proceedings of the 11th MIBES Conference, Heraklion, Greece, 20–22 June 2016; pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R.A. Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1995, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Verónica, S. Inequality and Economic Growth: A Dynamic Analysis. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2019, 52, 89–118. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.S.; Matthew, K. The moral consequences of economic growth: An empirical investigation. J. Socio-Econ. 2013, 42, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, P. Research on the Law of National Quality Development—A New Theory of National Quality Science, 1st ed.; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, N.; Hansen, P. Health Care Spending and Economic Output: Granger Causality. Appl. Econ. 2001, 8, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sub-Factor | Index | Description | Variable Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | Proportion of people aged under 15 years | X1 | |

| Proportion of people aged above 65 years | X2 | ||

| Dependency ratio | The population excluding people aged 15–64/the population of people aged between 15 and 64 | X3 | |

| Average life expectancy | X4 | ||

| Features of Labor Force | Labor force population | Employment and registered unemployment. Due to the lack of rural data, we only measured the urban features of labor force. | X5 |

| The ratio of the labor force population | X6 | ||

| The growth rate of the labor force | X7 | ||

| The proportion of the female labor force | X8 | ||

| Employment Conditions | Employed population | Due to the lack of rural data, we only measured the urban employment conditions. | X9 |

| Employment rate | X10 | ||

| The growth rate of employment | X11 | ||

| The proportion of agriculture employment | X12 | ||

| The proportion of industrial employment | X13 | ||

| The proportion of service industry employment | X14 | ||

| Unemployment rate | X15 | ||

| National Education | The proportion of people with higher education | X16 | |

| Student–teacher ratio (primary education) | Number of pupils per teacher (primary education, including regular primary schools) | X17 | |

| Student–teacher ratio (secondary education) | Number of pupils per teacher (secondary education, including regular high schools, secondary vocational education, and regular junior high school) | X18 | |

| The weights of public education expenditure in GDP | X19 | ||

| Illiteracy rate | The proportion of illiterate adults (over 15 years old) | X20 | |

| Life quality | The proportion of the urban population | X21 | |

| Engel’s Coefficient of Urban Households | The ratio of expenditure on food per urban household | X22 | |

| Engel’s Coefficient of Rural Households | The ratio of expenditure on food per rural household | X23 | |

| The proportion of women in village committees and neighborhood committees | The proportion of women in village committees and neighborhood committees refers to a proxy variable for the proportion of women in Congress | X24 | |

| Frequency of traffic accidents | The index of morality | X25 |

| Index | Calculation Method | Data Resource |

|---|---|---|

| Weighted Residential Consumption, CISEW | CISEW = Per Capita Residential Consumption Expenditure × Inequality Index of Income Distribution | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Services of Household Labor, GISEW | GISEW = GDP × 30% | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Services from durable consumer goods, IISEW | IISEW = Per Capita Residential Consumption Expenditure on Consumer Durables × 10% | Statistical Yearbook of Provinces |

| Public expenditure cost, W | W = 75% × Infrastructure Spending + 50% × Public Expenditure on Health and Education | CSMAR |

| Social expenditure cost, D | D = Cost of Commuting + Cost of Car Accidents + Urbanization Cost | Statistical Yearbook of Provinces |

| Environmental expenditure cost, E | E = Cost of Water Pollution + Cost of Air Pollution + Cost of Long-term Environmental Damage | China Energy Statistical Yearbook, Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China, National Bureau of Statistics |

| Components | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Proportion of population aged below 15 years | −0.091 | 0.041 | 0.044 | −0.175 | 0.185 | 0.100 |

| Proportion of population aged 65 years and over | −0.006 | 0.000 | 0.046 | −0.018 | 0.387 | 0.028 |

| Dependency ratio | 0.110 | −0.035 | 0.007 | 0.129 | −0.054 | −0.059 |

| Average life expectancy | 0.105 | −0.012 | −0.051 | −0.149 | −0.008 | 0.003 |

| Labor force population | −0.058 | 0.052 | −0.287 | 0.191 | 0.017 | 0.125 |

| Labor force ratio | 0.005 | 0.204 | −0.006 | 0.081 | 0.067 | 0.093 |

| Labor force growth rate | −0.010 | 0.185 | 0.035 | −0.056 | 0.024 | −0.076 |

| Proportion of female labor force | 0.019 | −0.169 | −0.036 | 0.019 | 0.074 | 0.041 |

| Employed population | −0.059 | 0.054 | −0.287 | 0.192 | 0.021 | 0.129 |

| Employment rate | 0.005 | 0.204 | −0.009 | 0.075 | 0.070 | 0.106 |

| Employment growth rate | −0.010 | 0.185 | 0.035 | −0.059 | 0.028 | −0.075 |

| Ratio of population employed in agriculture | 0.087 | 0.044 | 0.111 | −0.171 | 0.188 | −0.399 |

| Ratio of population employed in industry | −0.029 | 0.036 | 0.182 | 0.010 | −0.174 | 0.291 |

| Ratio of population employed in service industry | 0.104 | 0.012 | 0.002 | −0.017 | 0.067 | 0.258 |

| Unemployment rate | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.026 | −0.194 | 0.072 | 0.493 |

| Proportion of people with higher education | 0.125 | 0.014 | 0.062 | −0.037 | −0.059 | 0.137 |

| Student–teacher ratio (primary education) | 0.069 | −0.024 | 0.080 | 0.279 | −0.168 | −0.092 |

| Student–teacher ratio (secondary education) | 0.084 | 0.028 | −0.044 | 0.203 | 0.084 | 0.027 |

| Percentage of public education expenditure in GDP | −0.047 | 0.055 | 0.116 | 0.189 | 0.089 | 0.099 |

| Illiteracy rate | 0.125 | −0.029 | 0.063 | −0.132 | −0.048 | −0.003 |

| Proportion of urban population | 0.129 | −0.009 | −0.006 | −0.150 | 0.074 | −0.038 |

| Urban Engel coefficient | −0.031 | 0.007 | −0.076 | 0.559 | 0.017 | −0.035 |

| Rural Engel coefficient | 0.006 | −0.031 | 0.105 | 0.059 | −0.646 | 0.080 |

| Proportion of women in village committees and neighborhood committees | 0.126 | 0.042 | 0.062 | −0.056 | 0.066 | −0.073 |

| Frequency of traffic accidents | 0.029 | 0.108 | 0.261 | 0.141 | −0.171 | −0.040 |

| Factor | Initial Eigenvalue | Extract Loading Sum of Squares | Rotational Loading Sum of Squares | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance, % | Cumulative, % | Total | Variance, % | Cumulative, % | Total | Variance, % | Cumulative, % | |

| 1 | 8.383 | 33.531 | 33.531 | 8.383 | 33.531 | 33.531 | 7.762 | 31.050 | 31.050 |

| 2 | 5.600 | 22.402 | 55.932 | 5.600 | 22.402 | 55.932 | 5.142 | 20.570 | 51.619 |

| 3 | 3.386 | 13.544 | 69.476 | 3.386 | 13.544 | 69.476 | 3.786 | 15.142 | 66.762 |

| 4 | 1.461 | 5.845 | 75.322 | 1.461 | 5.845 | 75.322 | 1.562 | 6.250 | 73.011 |

| 5 | 1.389 | 5.557 | 80.879 | 1.389 | 5.557 | 80.879 | 1.533 | 6.131 | 79.142 |

| 6 | 1.068 | 4.273 | 85.153 | 1.068 | 4.273 | 85.153 | 1.503 | 6.011 | 85.153 |

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 1.277 | 1.223 | 1.19 | 1.209 | 1.242 | 1.2 | 1.24 | 1.143 | 1.321 | 1.297 |

| Tianjin | 0.922 | 0.969 | 0.163 | 0.225 | 0.953 | 0.252 | 0.761 | 0.933 | 0.472 | 0.165 |

| Hebei | −0.234 | −0.202 | −0.268 | −0.315 | −0.343 | −0.155 | −0.347 | −0.28 | −0.239 | −0.015 |

| Shanxi | −0.035 | 0.012 | 0.184 | 0.322 | 0.219 | 0.245 | 0.218 | 0.182 | 0.218 | 0.077 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.065 | 0.009 | 0.351 | 0.449 | 0.127 | 0.073 | 0.107 | 0.164 | 0.615 | 0.15 |

| Liaoning | 0.182 | 0.229 | 0.21 | 0.266 | −0.111 | 0.095 | 0.168 | 0.133 | 0.211 | 0.243 |

| Jilin | −0.103 | −0.045 | 0.154 | 0.129 | 0.068 | −0.032 | 0.067 | 0.161 | 0.287 | 0.019 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.295 | 0.179 | 0.268 | 0.388 | 0.116 | 0.281 | 0.33 | 0.317 | 0.182 | 0.138 |

| Shanghai | 0.825 | 0.545 | 0.539 | 0.419 | 0.592 | 0.605 | 0.692 | 0.51 | 0.608 | 0.825 |

| Jiangsu | −0.041 | −0.274 | −0.29 | −0.263 | −0.221 | 0.49 | −0.2 | −0.319 | −0.17 | 0.056 |

| Zhejiang | −0.443 | 0.08 | −0.45 | −0.301 | −0.356 | −0.095 | −0.232 | −0.147 | −0.258 | 0.018 |

| Anhui | −0.297 | −0.145 | −0.369 | −0.311 | −0.302 | −0.074 | −0.33 | −0.383 | −0.372 | −0.254 |

| Fujian | −0.291 | −0.272 | −0.439 | −0.38 | −0.271 | −0.326 | −0.354 | −0.389 | −0.301 | −0.398 |

| Jiangxi | −0.038 | −0.125 | −0.192 | −0.159 | −0.119 | −0.127 | −0.267 | −0.229 | −0.133 | −0.325 |

| Shandong | −0.076 | −0.35 | −0.268 | −0.343 | −0.343 | 0.377 | −0.394 | −0.517 | −0.306 | −0.153 |

| Henan | −0.433 | −0.334 | −0.35 | −0.104 | −0.238 | 0.019 | −0.421 | −0.394 | −0.367 | −0.325 |

| Hubei | −0.368 | −0.35 | −0.213 | −0.165 | −0.136 | −0.438 | 0.372 | 0.332 | −0.184 | −0.321 |

| Hunan | −0.088 | −0.281 | −0.256 | −0.188 | −0.281 | 0.036 | −0.231 | −0.263 | −0.148 | −0.27 |

| Guangdong | −0.626 | −0.481 | −0.155 | −0.614 | −0.502 | 0.131 | −0.352 | −0.387 | −0.392 | −0.031 |

| Guangxi | 0.034 | −0.088 | −0.037 | −0.199 | −0.136 | −0.092 | −0.24 | −0.026 | 0.024 | −0.473 |

| Hainan | 0.261 | 0.573 | 0.298 | 0.484 | 0.263 | −0.179 | 0.234 | 0.16 | −0.037 | 0.193 |

| Chongqing | 0.047 | 0.084 | −0.104 | −0.014 | 0.016 | 0.06 | −0.026 | −0.101 | −0.062 | −0.2 |

| Sichuan | −0.409 | −0.583 | −0.471 | −0.453 | −0.359 | −0.131 | −0.341 | −0.399 | −0.354 | −0.075 |

| Guizhou | −0.167 | −0.145 | −0.087 | −0.056 | −0.065 | −0.237 | −0.235 | −0.295 | −0.338 | −0.477 |

| Yunnan | −0.519 | −0.319 | −0.398 | −0.466 | −0.464 | −0.57 | −0.367 | −0.148 | −0.504 | −0.269 |

| Xizang | −0.007 | 0.127 | 0.335 | 0.06 | 0.137 | −0.702 | −0.078 | 0.133 | 0.095 | 0.791 |

| Shaanxi | −0.287 | −0.222 | −0.003 | −0.164 | −0.178 | −0.208 | −0.216 | −0.1 | −0.081 | −0.311 |

| Gansu | 0.021 | 0.098 | 0.202 | 0.289 | 0.346 | 0.06 | 0.211 | 0.076 | 0.164 | −0.083 |

| Qinghai | 0.172 | 0.112 | 0.293 | 0.154 | 0.219 | −0.204 | 0.034 | 0.115 | 0.014 | 0.104 |

| Ningxia | 0.287 | 0.016 | 0.112 | 0.063 | 0.184 | −0.1 | 0.175 | 0.101 | 0.045 | −0.082 |

| Xinjiang | 0.073 | −0.041 | 0.051 | 0.038 | −0.056 | −0.254 | 0.026 | −0.085 | −0.01 | −0.016 |

| Province | Average Score | National Quality Ranking | National Quality Level Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 1.2342 | 1 | Provinces with High Level of National Quality |

| Shanghai | 0.616 | 2 | |

| Tianjin | 0.5815 | 3 | |

| Heilongjiang | 0.2494 | 4 | |

| Hainan | 0.225 | 5 | |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.211 | 6 | |

| Shanxi | 0.1642 | 7 | |

| Liaoning | 0.1626 | 8 | |

| Gansu | 0.1384 | 9 | |

| Qinghai | 0.1013 | 10 | |

| Xizang | 0.0891 | 11 | |

| Ningxia | 0.0801 | 12 | |

| Jilin | 0.0705 | 13 | |

| Xinjiang | −0.0274 | 14 | |

| Chongqing | −0.03 | 15 | |

| Jiangsu | −0.1232 | 16 | Provinces with Low Level of National Quality |

| Guangxi | −0.1233 | 17 | |

| Hubei | −0.1471 | 18 | |

| Jiangxi | −0.1714 | 19 | |

| Shaanxi | −0.177 | 20 | |

| Hunan | −0.197 | 21 | |

| Guizhou | −0.2102 | 22 | |

| Zhejiang | −0.2184 | 23 | |

| Shandong | −0.2373 | 24 | |

| Hebei | −0.2398 | 25 | |

| Anhui | −0.2837 | 26 | |

| Henan | −0.2947 | 27 | |

| Guangdong | −0.3409 | 28 | |

| Fujian | −0.3421 | 29 | |

| Sichuan | −0.3575 | 30 | |

| Yunnan | −0.4024 | 31 |

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 3.644 | 3.957 | 4.482 | 4.727 | 5.149 | 5.447 | 6.180 | 6.784 | 6.416 | 5.627 |

| Tianjin | 2.363 | 2.638 | 2.725 | 3.116 | 3.171 | 3.414 | 3.772 | 5.158 | 4.345 | 3.385 |

| Hebei | 1.013 | 1.166 | 1.046 | 1.155 | 1.205 | 1.352 | 1.568 | 3.239 | 1.788 | 2.138 |

| Shanxi | 0.338 | 0.377 | 0.159 | 0.094 | −0.150 | −0.087 | 0.124 | 1.229 | 0.396 | 0.384 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.341 | 0.349 | 0.284 | 0.307 | 0.419 | 0.606 | 0.620 | 1.287 | 0.035 | −0.394 |

| Liaoning | 1.422 | 1.589 | 1.495 | 1.579 | 1.764 | 1.914 | 2.042 | 2.655 | 2.320 | 1.932 |

| Jilin | 1.192 | 1.318 | 1.236 | 1.396 | 1.550 | 1.707 | 1.789 | 1.846 | 2.538 | 2.230 |

| Heilongjiang | 1.119 | 1.235 | 1.206 | 1.271 | 1.309 | 1.364 | 1.439 | 1.615 | 2.196 | 1.315 |

| Shanghai | 3.611 | 3.791 | 4.184 | 4.385 | 4.822 | 5.490 | 5.998 | 4.626 | 4.576 | 4.637 |

| Jiangsu | 2.411 | 2.574 | 2.726 | 2.927 | 3.230 | 3.460 | 3.952 | 3.544 | 3.902 | 3.714 |

| Zhejiang | 2.589 | 2.649 | 2.776 | 3.041 | 3.210 | 3.380 | 3.646 | 3.135 | 3.417 | 3.077 |

| Anhui | 1.317 | 1.574 | 1.269 | 1.502 | 1.572 | 1.800 | 1.976 | 2.160 | 2.452 | 2.282 |

| Fujian | 2.079 | 2.333 | 2.302 | 2.607 | 2.914 | 3.098 | 3.517 | 3.601 | 3.889 | 3.656 |

| Jiangxi | 1.310 | 1.506 | 1.386 | 1.546 | 1.685 | 1.842 | 2.058 | 2.585 | 2.641 | 2.065 |

| Shandong | 1.535 | 1.640 | 1.584 | 1.738 | 1.886 | 2.084 | 2.243 | 2.445 | 2.235 | 2.005 |

| Henan | 1.221 | 1.437 | 1.212 | 1.381 | 1.552 | 1.640 | 1.890 | 2.494 | 2.276 | 2.160 |

| Hubei | 1.469 | 1.765 | 1.774 | 1.936 | 2.138 | 2.399 | 2.706 | 3.259 | 2.979 | 2.903 |

| Hunan | 1.500 | 1.703 | 1.554 | 1.811 | 1.995 | 2.137 | 2.289 | 2.627 | 2.671 | 2.595 |

| Guangdong | 2.384 | 2.610 | 2.316 | 2.623 | 2.979 | 3.313 | 3.499 | 3.119 | 3.542 | 3.195 |

| Guangxi | 1.271 | 1.464 | 1.143 | 1.329 | 1.520 | 1.599 | 1.767 | 2.160 | 2.293 | 1.943 |

| Hainan | 1.517 | 1.671 | 1.592 | 1.772 | 1.867 | 2.038 | 2.215 | 2.502 | 2.694 | 2.527 |

| Chongqing | 1.687 | 1.868 | 1.783 | 1.982 | 2.218 | 2.459 | 2.752 | 2.813 | 3.194 | 2.963 |

| Sichuan | 1.514 | 1.616 | 1.491 | 1.612 | 1.830 | 1.976 | 2.288 | 2.543 | 2.782 | 2.577 |

| Guizhou | 0.803 | 0.942 | 0.732 | 0.958 | 1.116 | 1.317 | 1.476 | 1.992 | 2.665 | 2.021 |

| Yunnan | 1.131 | 1.353 | 1.120 | 1.289 | 1.432 | 1.586 | 1.851 | 4.258 | 3.205 | 2.528 |

| Shaanxi | 1.456 | 1.580 | 1.351 | 1.427 | 1.561 | 1.655 | 1.816 | 4.008 | 2.010 | 2.179 |

| Gansu | 0.956 | 1.192 | 0.947 | 1.067 | 1.127 | 1.325 | 1.437 | 2.294 | 1.799 | 1.787 |

| Qinghai | 1.095 | 1.235 | 1.225 | 1.415 | 1.589 | 1.724 | 1.925 | 2.868 | 2.210 | 2.281 |

| Ningxia | 0.010 | 0.137 | −0.116 | −0.006 | 0.094 | 0.253 | −0.028 | 0.489 | −0.362 | −0.899 |

| Xinjiang | 1.073 | 1.247 | 0.952 | 0.922 | 0.960 | 1.048 | 1.187 | 2.252 | 1.523 | 1.169 |

| Province | Average ISEW | Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 5.2413 | 1 |

| Shanghai | 4.612 | 2 |

| Tianjin | 3.4087 | 3 |

| Jiangsu | 3.244 | 4 |

| Zhejiang | 3.092 | 5 |

| Fujian | 2.9996 | 6 |

| Guangdong | 2.958 | 7 |

| Chongqing | 2.3719 | 8 |

| Hubei | 2.3328 | 9 |

| Hunan | 2.0882 | 10 |

| Hainan | 2.0395 | 11 |

| Sichuan | 2.0229 | 12 |

| Yunnan | 1.9753 | 13 |

| Shandong | 1.9395 | 14 |

| Shaanxi | 1.9043 | 15 |

| Liaoning | 1.8712 | 16 |

| Jiangxi | 1.8624 | 17 |

| Anhui | 1.7904 | 18 |

| Qinghai | 1.7567 | 19 |

| Henan | 1.7263 | 20 |

| Jilin | 1.6802 | 21 |

| Guangxi | 1.6489 | 22 |

| Hebei | 1.567 | 23 |

| Heilongjiang | 1.4069 | 24 |

| Guizhou | 1.4022 | 25 |

| Gansu | 1.3931 | 26 |

| Xinjiang | 1.2333 | 27 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.3854 | 28 |

| Shanxi | 0.2864 | 29 |

| Ningxia | −0.0428 | 30 |

| Years | Pearson Correlation Coefficient of National Quality and ISEW | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 0.393 ** | 0.031 |

| 2012 | 0.438 ** | 0.016 |

| 2013 | 0.294 | 0.115 |

| 2014 | 0.200 | 0.289 |

| 2015 | 0.360 * | 0.051 |

| 2016 | 0.570 *** | 0.001 |

| 2017 | 0.417 ** | 0.022 |

| 2018 | 0.454 ** | 0.012 |

| 2019 | 0.231 | 0.220 |

| 2020 | 0.410 ** | 0.024 |

| Data Format | Index | Test Methods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPS | ADF-Fisher | |||||

| Index | Variable Name | IPS Value | p Value | ADF-Fisher Value | p Value | |

| Date of levels | ISEW | Y | −2.0471 | 0.0203 | 11.2975 | 0.0000 |

| Proportion of population aged below 15 years | X1 | −3.8881 | 0.0001 | 13.8603 | 0.0000 | |

| Proportion of population aged 65 years and over | X2 | −4.5382 | 0.0000 | 14.7418 | 0.0000 | |

| Dependency ratio | X3 | −2.4808 | 0.0066 | 11.7212 | 0.0000 | |

| Average life expectancy | X4 | 5.2176 | 1.0000 | 1.8704 | 0.0307 | |

| Labor force population | X5 | 5.8119 | 1.0000 | 2.3287 | 0.0099 | |

| Percentage of labor force population | X6 | 0.8515 | 0.8027 | 7.5536 | 0.0000 | |

| Growth rate of labor force | X7 | −16.8142 | 0.0000 | 28.9487 | 0.0000 | |

| Proportion of female labor force | X8 | 0.7196 | 0.7641 | 8.2669 | 0.0000 | |

| Employed population | X9 | 5.7663 | 1.0000 | 2.2934 | 0.0109 | |

| Employment rate | X10 | 0.7973 | 0.7874 | 7.7260 | 0.0000 | |

| Employment growth rate | X11 | −16.7056 | 0.0000 | 28.8722 | 0.0000 | |

| Proportion of agriculture employment | X12 | −13.9603 | 0.0000 | 28.2504 | 0.0000 | |

| Proportion of industrial employment | X13 | 1.2498 | 0.8943 | 8.2154 | 0.0000 | |

| Proportion of service industry employment | X14 | 3.4912 | 0.9998 | 5.6663 | 0.0000 | |

| Unemployment rate | X15 | 0.9910 | 0.8392 | 7.7260 | 0.0000 | |

| Percentage of population with higher education degrees | X16 | −4.3521 | 0.0000 | 14.3846 | 0.0000 | |

| Student–teacher ratio (primary education) | X17 | −0.9393 | 0.1738 | 10.3537 | 0.0000 | |

| Student–teacher ratio (secondary education) | X18 | −4.5286 | 0.0000 | 13.4477 | 0.0000 | |

| Weights of public education expenditure in GDP | X19 | −1.7657 | 0.0387 | 10.8515 | 0.0000 | |

| Illiteracy rate | X20 | −1.9751 | 0.0241 | 11.1441 | 0.0000 | |

| Urban population | X21 | 4.0235 | 1.0000 | 3.9462 | 0.0000 | |

| Engel’s Coefficient of Urban Households | X22 | −6.0242 | 0.0000 | 15.8059 | 0.0000 | |

| Engel’s Coefficient of Rural Households | X23 | −7.1633 | 0.0000 | 15.4370 | 0.0000 | |

| Proportion of women in village committees and neighborhood committees | X24 | 1.7580 | 0.0394 | 10.7478 | 0.0000 | |

| Frequency of traffic accidents | X25 | 2.7072 | 0.9966 | 5.2165 | 0.0000 | |

| Average life expectancy | X4 | −27.4869 | 0.0000 | 13.4422 | 0.0000 | |

| Labor force population | X5 | −1.5905 | 0.0559 | 3.4194 | 0.0003 | |

| Ratio of labor force population | X6 | −3.5966 | 0.0002 | 4.3397 | 0.0000 | |

| The proportion of the female labor force | X8 | −1.7041 | 0.0442 | 10.9323 | 0.0000 | |

| Employed population | X9 | −1.8704 | 0.0307 | 6.0871 | 0.0000 | |

| Employment rate | X10 | −4.7746 | 0.0000 | 4.4357 | 0.0000 | |

| Proportion of industrial employment | X13 | −2.9655 | 0.0015 | 11.9595 | 0.0000 | |

| Proportion of service industry employment | X14 | −3.9369 | 0.0000 | 13.0636 | 0.0000 | |

| Unemployment rate | X15 | −6.0203 | 0.0000 | 15.9677 | 0.0000 | |

| Student–teacher ratio (primary education) | X17 | −5.9289 | 0.0000 | 15.4195 | 0.0000 | |

| Urban population | X21 | −5.6559 | 0.0000 | 15.5085 | 0.0000 | |

| Frequency of traffic accidents | X25 | −8.9034 | 0.0000 | 19.5053 | 0.0000 | |

| Null Hypothesis | Z-Statistic | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| The weights of public education expenditure in GDP are not a Granger cause of ISEW. | −0.4762 | 0.6340 |

| ISEW is not a Granger cause of the weights of public education expenditure in GDP. | 0.8453 | 0.3980 |

| ISEW is not a Granger cause of the urban household Engel’s coefficient. | −0.7231 | 0.4696 |

| ISEW is not a Granger cause of traffic accident frequency. | 0.7316 | 0.4644 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; You, S.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y. National Quality and Sustainable Development: An Empirical Analysis Based on China’s Provincial Panel Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064879

Li S, You S, Liu D, Wang Y. National Quality and Sustainable Development: An Empirical Analysis Based on China’s Provincial Panel Data. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):4879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064879

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Sidan, Shibing You, Duochenxi Liu, and Yukun Wang. 2023. "National Quality and Sustainable Development: An Empirical Analysis Based on China’s Provincial Panel Data" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 4879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064879

APA StyleLi, S., You, S., Liu, D., & Wang, Y. (2023). National Quality and Sustainable Development: An Empirical Analysis Based on China’s Provincial Panel Data. Sustainability, 15(6), 4879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064879