Abstract

The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, two major agricultural powers, has numerous severe socio-economic consequences that are presently being felt worldwide and that are undermining the functioning of the global food system. The war has also had a profound impact on the European food system. Accordingly, this paper examines the implications of the ongoing conflict on food security pillars (viz. availability, access, use, stability) in European countries and considers potential strategies for addressing and mitigating these effects. The paper highlights that the food supply in Europe does not seem to be jeopardized since most European countries are generally self-sufficient in many products. Nonetheless, the conflict might impact food access and production costs. Indeed, the European agricultural industry is a net importer of several commodities, such as inputs and animal feed. This vulnerability, combined with the high costs of inputs such as fertilizers and energy, creates production difficulties for farmers and threatens to drive up food prices, affecting food affordability and access. Higher input prices increase production costs and, ultimately, inflation. This may affect food security and increase (food) poverty. The paper concludes that increasing food aid, ensuring a stable fertilizer supply, imposing an energy price cap, initiating a farmer support package, switching to renewable energy sources for cultivation, changing individual food behaviors, lifting trade restrictions, and political stability can safeguard food security pillars and strengthen the resilience of the European food system.

Keywords:

food security; food security pillars; food supply; food; energy; conflict; Russia; Ukraine; war 1. Introduction

During the past decades, the global food system has faced several crises, including climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic, causing market and supply chain disruption and raising concerns about food security. Consequently, food prices have been increasing since the middle of 2021 due to supply chain disruptions brought on by the pandemic [1], rising global demand, and poor harvests in several countries [2,3]. Fuel, fertilizer, and pesticide prices have also increased to nearly record levels [4,5]. Further, the FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) surpassed a new record in February 2022, rising by 2.2% from the previous peak in February 2011 and by 21% in the year prior [6,7]. Since most European countries depend on imports to meet their energy demand, the continent has seen skyrocketing costs beginning in the summer of 2021. The rise in energy prices hit many of the inputs used by European farmers, such as feed and fertilizers. Hence, annual inflation in the European Union (EU) reached 5.2% in November 2021 (4.9% in the Euro area), 27.5% in the energy sector, and 2.2% in the food, alcohol, and tobacco sector [5].

In the early hours of 24 February 2022, Russia began a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine, resulting in civilian casualties and the destruction of vital infrastructure. In addition to significant human fatalities and devastation, the war has jeopardized global food security by disrupting agriculture production and trade in one of the world’s most significant food-exporting regions [8,9,10,11,12]. It has significantly contributed to rapidly rising global food prices, aggravating existing food system vulnerabilities already worsened by climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic [13,14]. A year into the conflict, its final military implications and outcomes are unknown [15]. However, its impacts on agricultural production and food security are clear [11,12,16,17]. It has caused a severe drop in both countries’ exports and production of essential commodities (e.g., cereals). Their price has soared worldwide, threatening to force millions into famine and poverty, especially in Low-Income Food-Deficit Countries (LIFDCs) [11,12,16,17]. The European Commission [17] predicted that up to 25 million tons of wheat would need to be substituted to meet global food demands for the current and upcoming seasons.

While Russia and Ukraine contribute just about 2% of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP), they are both global breadbaskets, producing and exporting essential agricultural commodities, minerals, fertilizers, and energy [18,19,20]. These countries supply about 30% of globally traded wheat, 20% corn, and 70% sunflower oil. Hence, in 2021, they were among the top three global wheat and corn exporters, accounting for more than 50% and 25% of all sunflower oil sold worldwide [7]. Overall, Russia and Ukraine export around 12% of the global total caloric trade [4]. Furthermore, before the conflict, Russia was the world’s largest supplier of fertilizers (such as nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus) and one of the leading oil and natural gas exporters, owing to its vast reserves [10,21,22,23].

Accordingly, the conflict dealt a considerable blow to commodity markets, particularly food, fertilizers, and energy, impacting global trade, production, and consumption patterns in ways that will keep prices at historic highs until the end of 2024, jeopardizing global food security [11,12]. Higher energy, input, and food prices might considerably impact global food security, particularly in vulnerable countries. Because of the interdependence inherent in international trade, the broader repercussions are felt throughout the globe in today’s hyper-connected global economy with its deep trade ties [24]. According to the World Bank [24], in January 2023, maize and wheat prices were 27% and 13% higher, respectively, than in January 2021, while rice price was 10% lower. Therefore, between September and December 2022, 94.1% of low-income nations, 92.9% of lower-middle-income countries, and 89% of upper-middle-income countries had inflation exceeding 5%, with several having double-digit inflation [25]. High inflation is also prevalent in high-income countries, including some in Europe, with around 85.5% suffering high food price inflation [26].

The conflict has also significantly affected the European food system, which was already dealing with interrupted supply lines due to the COVID-19 outbreak [27]. The food supply in the EU is not jeopardized, since most European countries benefit from well-developed agricultural production and are mostly self-sufficient in many products. However, the European agricultural sector is a net importer of specific products, such as animal feed. This vulnerability, combined with the high costs of inputs such as fertilizers and energy, creates production difficulties for farmers and threatens to drive up food prices, affecting food availability and access [28]. Indeed, the substantial dependence of some European nations on the Russian energy supply makes it hard to avoid price increases on essential items such as food [29]. This increases producer costs and affects food prices, raising worries over consumer purchasing power and producer income. Inflation affects the price of basic commodities, particularly for low-income households, for whom the affordability of nutritious meals was already a challenge before the start of the conflict [29]. The conflict highlighted the European food system’s vulnerabilities, such as its dependence on imported energy, fertilizer, and animal feed [18]. In 2019, Russia supplied the European Union with over 40% of its natural gas, 25% of its oil, and almost 50% of its coal [30].

After decades of low inflation, the EU faces new economic, political, and social challenges from increasing consumer prices. Rising energy and food prices are already generating high societal costs in terms of decreased buying power. They are also anticipated to exacerbate material deprivation, poverty, and social exclusion throughout the EU [31]. The next several months will be among the most challenging in modern history for the European and global agri-food sectors [10]. Although futures prices have gone down and international markets have adjusted and adapted, there is a possibility of a short-term inflation increase due to the delayed transmission of previous food and energy price increases from global commodity markets to consumer prices. For instance, the IMF [31] predicts that global inflation will climb from 4.7% in 2021 to 8.8% in 2022 before falling to 6.5% in 2023 and 4.1% in 2024. In Europe, the effects are compounded by the significant impact of war-related energy shocks [31].

In this context, this paper aims to assess the possible impacts of the war between Russia and Ukraine on food security in European countries. It aims to address these two questions: Firstly, what were the principal consequences of the conflict on food security in European countries, and how significant were they? Secondly, how did the war affect the food security condition of European populations?

Several scholars, government representatives, and media outlets have examined the implications of the Russia–Ukraine conflict on food security. However, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to specifically examine the impact of the Russia–Ukraine conflict on food security in Europe. Despite the numerous studies conducted on the topic, none have expressly focused on this region and the possible repercussions it may face due to the ongoing conflict. Most of the existing research focused on the impact of the conflict on global food security [11,12,30,32,33,34,35], energy security [16,36], or its economic implications [37,38]. Accordingly, this research aims to fill that gap by providing a comprehensive examination of the impact of the Russia–Ukraine conflict on food security in Europe, including the potential risks and challenges that may arise, as well as potential strategies for mitigating those risks. By providing this information, we hope to contribute to a better understanding of the complex relationship between conflicts and food security in Europe and beyond.

While food security is only one aspect of the consequences of the war, it is a critical one that affects the well-being of millions worldwide. Therefore, the focus on the impact of the war on food security is vital because it highlights the urgent need for measures to address these issues. It is also worth noting that food security is interconnected with other aspects of the war’s consequences, such as inflation, poverty, and social instability. Therefore, by addressing food security, it is possible to have positive ripple effects on other aspects of the conflict’s consequences.

The impacts of the war exhibit regional variability and may even differ among countries within the same region. Other regions of the world that may be more seriously affected by the impact of the war on food security, such as the Middle East and the North Africa (MENA) region [39], might have different dynamics and factors at play that require different policy interventions. To better grasp the far-reading and multifaceted effects of the war on the global food system, it is paramount to have analyses relating to developing and developed countries (e.g., the European Union). By focusing specifically on the impact of the Russian–Ukrainian conflict on food security in Europe, the paper provides targeted policy recommendations tailored to the region’s specific context and challenges. In the context of the conflict, it is crucial to consider the unique dynamics and factors in each area to develop effective solutions.

2. Materials and Methods

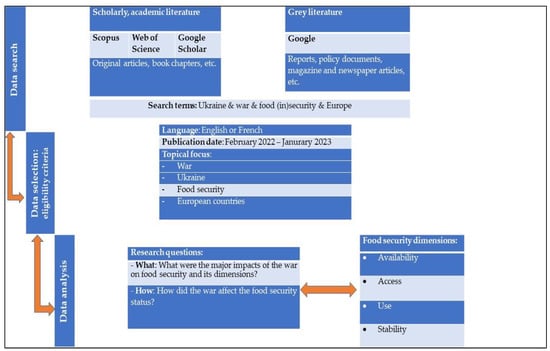

A specific search strategy and an article selection criterion are incorporated into the methodology (Figure 1). The article draws upon both the scholarly literature and the grey literature. In both cases, strict and well-defined inclusion criteria were used so that only documents that deal with the war in Ukraine and its impacts on food security (and its different pillars) were considered eligible and included in the present review. As for the scholarly literature, we used forward and backward searches on the most important databases, namely Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, which is the most effective way to find peer-reviewed literature (individually or Boolean combined). Figure 1 contains the search string used, focusing primarily on “food security”, Ukraine, war, and Europe. For instance, in the case of the Web of Science, the search returned 18 documents [12,17,23,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. The terms were chosen to capture the broadest range of the literature relevant to our research question. Using multiple databases and a combination of search terms ensured that we identified a comprehensive and diverse range of the literature on the topic, which was then carefully evaluated for relevance, eligibility, and quality. This approach enabled us to identify the most relevant and recent literature on the impact of the Russia–Ukraine conflict on food security in Europe.

Figure 1.

Data search, selection, and analysis. Source: authors’ elaboration.

The grey literature was located using Google and included reports, policy documents, magazine and newspaper articles, and technical and working papers produced by regional and international organizations (e.g., Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), World Food Program (WFP), World Bank, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), World Economic Forum (WEF), European Commission, European Council, European Committee of the Regions, European Parliament (EP), European Investment Bank), Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS), Food Security Portal, consulting firms (e.g., McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group, KPMG, etc.), and international newspapers and news platforms (e.g., Food Business News, Geneva Environment Network, Bloomberg, Deutsche Welle, Euronews, Financial Times, The Guardian).

This method enabled us to collect a broad range of information from various sources, including government reports, news articles, and other pertinent documents that give a thorough knowledge of the effect of the Russia–Ukraine conflict on food security in Europe.

In accordance with the definition of food security, the analytical approach adopted in this research considers all four dimensions: availability, access, use, and stability [55]. The study aims to comprehensively analyze how the conflict has affected food security in Europe by assessing the various factors contributing to food insecurity. This includes evaluating the impact on food production, distribution, and consumption, as well as the stability of the food supply chain. Additionally, the research also examines the various strategies that have been implemented to mitigate the effects of the conflict on food security and assesses their effectiveness. Overall, the analytical approach adopted in this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the Ukrainian conflict on food security in European countries.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, we first analyze the threats posed by the war in Ukraine and other disruptions to food security and its pillars (viz. availability, access, utilization, and stability) before analyzing how the European Union can reshape and reconfigure its food system in order to ensure food security for its population amid the war crisis.

3.1. Threats Posed by War and Other Disruptions to Food Security

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine has undermined important food security tenets. Wars and military conflicts put countries at risk of international trade disruptions, particularly those that depend on imports of critical commodities such as oil and food [16]. Armed conflicts may negatively impact food security by generating shortages of upstream and downstream outputs, hurting food production, commercialization, and stock management [56]. War and violence continue to be the primary cause of hunger, with 60% of the world’s hungry population residing in regions affected by conflict. Further, in today’s globalized world, military conflicts may exacerbate food insecurity in regions beyond the battlefield [35]. Due to wars, a country’s agricultural production can be drastically reduced if crops cannot be planted, weeded, or harvested [57].

Farmers in Ukraine’s conflict-prone areas lost livestock, food supplies, and other assets, disrupting food market supply in these and other surrounding regions and neighboring countries. The destruction of civil infrastructure and the presence of mines and Unexploded Ordnances (UXOs) coupled with limitations on the movement of people and goods have made it difficult for farmers to tend to their fields, harvest their crops, and sell their livestock products [58]. Additionally, with conscription and population displacement, there was a significant labor shortage. Fertilizers and other critical agricultural inputs are becoming more limited, exacerbating the situation [15]. Further, the conflict-affected regions, such as Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, account for a significant portion of Ukraine’s pre-war output, with 25% of barley, 16% of sunflower seed, 20% of rapeseed, and 20% of wheat [59]. According to assessments, the conflict would cost farmers and agricultural corporations USD 28.3 billion this year in lost income, damage to farming machinery, equipment, storage facilities, livestock, and crops, and increased transportation costs [60].

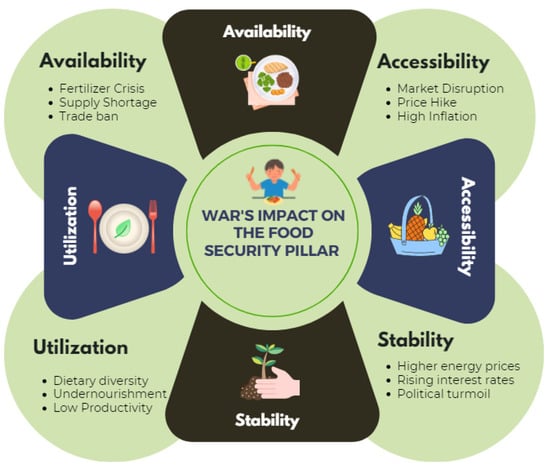

The conflict’s effects on global issues are too early to be determined, but it is evident they will be multifaceted [61]. The conflict has prompted widespread international concern over a global food crisis and its potential effects on food security (Figure 2). Indeed, a growing body of the literature shows that the war has affected food security at different levels and scales [12,17,23,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54], especially in developing countries that rely on food imports [12,42,44,45,51] and for some commodities such as wheat [47,52,53]. However, it seems that the impacts of the war have not been alike on the four pillars of food security. Furthermore, the extent of the war’s impact on the food security pillars will be determined by its length and the outcomes of the different scenarios.

Figure 2.

Ukrainian–Russian conflict and its consequences on food security pillars. Source: developed by the authors.

3.1.1. Availability

First and foremost, food security requires a sufficient amount of food needs to be available regularly. It focuses on determining what calories are available nationally or at the individual level (e.g., cereals or animal proteins), including the adequate supply of nutritional foods [55].

Ukraine has long been renowned as “Europe’s breadbasket” because of its abundance of “Chernozem”, or black soil, considered the most fertile farmland in the world, and has a high producing potential. Ukraine’s agricultural land area totals 41 million hectares, with 33 million hectares being arable, the equivalent of one-third of the EU’s total arable land area [62]. A significant fall in agricultural production and supply followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s and Russia and Ukraine became net importers of food [63]. However, Russian and Ukrainian agro-food output and exports have expanded considerably during the last three decades due to intense modernization and automation, making the region the world’s breadbasket [19]. In 2021, Russia and Ukraine exported nearly 12% of the food calories traded globally, making them essential actors in the global agri-food sector [23]. They are significant producers of staple agro-commodities such as wheat, corn, and sunflower oil and Russia is the largest exporter of fertilizers in the world. Further, Ukraine is one of the top three grain exporters, leading the world in soybean and sunflower oil exports. Ukraine controls 52.2% of the global sunflower oil market. Ukrainian agricultural exports have acquired a rising reputation in China, Egypt, India, Turkey, and the European Union [64].

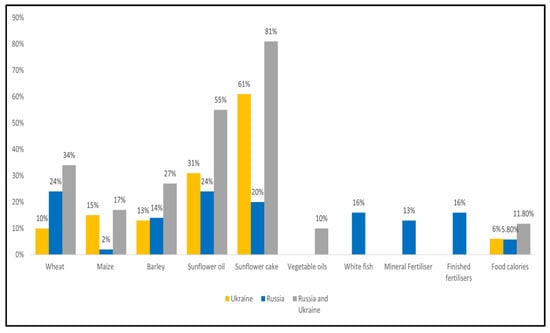

Figure 3 shows that in 2021, Ukraine and Russia combined trade accounts for over 34% of world wheat, 17% of corn, 27% of barley, and over 80% and 55% of sunflower cake and oil, respectively. The global trade in vegetable oils and food calories amounts to 10% and 11.80%, respectively. Furthermore, Russia exports 16% of fish (Alaska pollock), 13% of mineral fertilizers such as ammonia, phosphate rock, sulfur, and 16% of finished fertilizers [4].

Figure 3.

The proportion of Ukraine and Russia’s combined global exports in 2021. Source: authors’ estimations based on FAO [18] and AMIS market monitor data [65].

As a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, global markets were disrupted. Short-term disruptions in global grain supply and long-term effects on natural gas and fertilizer markets negatively impacted producers during the planting season. This disruption might exacerbate already high food price inflation, posing a significant threat to low-income net food importers, many of whom have suffered a rise in malnutrition rates due to the pandemic disruptions [4].

The European Commission [17] predicted that up to 25 million tons of wheat would need to be substituted to meet global food demands for the current and upcoming seasons. The Black Sea Grain Initiative’s inception and renewal, as well as measures to enhance export capacity through non-marine channels, have assisted in easing Ukraine’s strict export restrictions brought on by the shutdown of Black Sea ports at the onset of the conflict [23]. Over 9.3 million metric tons of grains, oilseeds, and other products have been shipped under the deal as of 28 October 2022. The agreement enables Ukraine to quadruple its exports above the pre-deal level, albeit it still functions at 50% of its pre-war 2021 level. Even while the deal did not completely address the problems with food exports from the conflict zone, it significantly relieved the strain on the existing markets and Ukrainian farmers who were unable to transport their commodities [66]. Consequently, Ukraine is expected to export 39.5 million tons of grain and oilseeds in 2022–23, while the country’s entire export potential is between 55 and 60 million tons [59]. Ukraine’s exports and grain production decreased by around 40% and 30% in 2022 compared with 2021. The decline in the wheat, maize, and sunflower harvests is estimated to be approximately 40–50%, 25%, and 35%, respectively, compared with 2021 [67].

Further, some issues will impact the 2023 harvest due to rising seed, transport, and fuel costs combined with low grain selling prices [68]. For instance, the transportation costs to ports have increased by over 100%, and the substitute option, which involves truck transport to Romania, costs nearly four times as much [69]. Accordingly, the sowing of winter wheat has decreased by 17% compared with the harvested area of 2022, while the estimated area for maize cultivation is reduced by 30% to 35% [67]. As a result, in 2023, Ukraine’s grain production and exports are anticipated to diminish by 20% and 15% compared with 2022. The grain exports may decline even more to 15 MT during the 2023/2024 season, a significant drop from the 54.9 MT recorded in 2019–2020 and 44.9 MT in 2020–2021 [67]. Additionally, despite reports that Russian food exports have persisted, there are fears that access to banking services required to execute foreign transactions may have hindered exports [23].

Furthermore, as was evident during the 2007–2008 food crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, many nations imposed export bans to ensure the availability of local foods and to reduce inflation (e.g., India for wheat; Serbia for grains and vegetable oils; Indonesia for palm oil), which exacerbates the situation [70]. Indeed, growing protectionism exacerbates the war’s impact on global food markets. Around 17% of total global food and feed exports (on a caloric basis) were impacted by export restrictions at their height in late May 2022. After May, many nations relaxed the restrictions to some degree: midway through July, it dropped to 7.3% of total trade being impacted and stayed relatively constant for the remainder of 2022. According to IFPRI’s Food and Fertilizer Export Restrictions Tracker, 32 countries implemented a total of 77 export restrictions in 2022. These limits included export license requirements, export taxes or duties, outright bans, or some combination of measures [71]. As of December 2022, 19 countries had imposed 23 food export bans, while 8 had adopted 12 export restriction measures [25]. These actions can potentially have severe unintended consequences for vulnerable populations in food-importing countries, boosting prices and deepening food insecurity issues already aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic [40,72]. Export limitations exacerbated severe deficits during the food crisis of 2007–2008, which led to riots across Asia and Africa [73].

In Europe, the food supply is not jeopardized since most European countries benefit from well-developed agricultural production. Except for tropical items (such as fruit, coffee, and tea), oilseeds (particularly soya), and natural fats and oils (including palm oil), the EU is self-sufficient in most food products [74]. The EU is generally self-sufficient in essential agricultural crops, including wheat and barley (which it is a net exporter of), maize, and sugar. The EU is also self-sufficient in a variety of animal products, including dairy and meat products, as well as fruits and vegetables [5]. Although Russia’s Ukraine conflict and climate change affect output, the EU’s food system remains robust and reliable. However, essential goods, such as animal feed, are net imported by the European agricultural industry. Due to this vulnerability and the high input costs, such as those for energy and fertilizers, farmers face productivity challenges and risk having food prices rise. This would reduce access to and availability of food [28]. Indeed, the substantial dependence of some European nations on the Russian energy supply makes it hard to avoid price increases on essential items such as food [29]. Ukraine was a key exporter of corn to Euro countries before the start of the conflict, accounting for 42% of EU grain imports in 2019, 30.5% in 2020, and 29.1% in 2021. Vegetable fat and oil imports from Ukraine were also significant, making up about 24% of EU imports between 2019 and 2021 before the crisis. Meanwhile, before the conflict, Russia accounted for approximately one-fifth of EU inorganic fertilizer imports. With the extensive usage of fertilizers in the EU, this may be destabilizing [29].

Some countries, such as Spain, are more vulnerable than others due to their high dependence on imports from Ukraine. The Spanish agricultural industry was already dealing with a significant increase in energy and other input costs, as well as a lengthy period of drought. The invasion of Ukraine is causing challenges in industries such as animal husbandry, the food industry, and food retailing. Indeed, Spain is a significant global pork exporter (China’s largest pig meat supplier), but pigs need a large quantity of grain and oilseed to reach marketable weight. However, it also has a structural shortage of grains [75]. Accordingly, Spain is a net importer of cereals, with Ukraine accounting for a significant portion of its imports. Ukraine is one of Spain’s most important agricultural trading partners, accounting for over 30% of its corn imports and 70% of its sunflower oil imports in 2021 [29]. In the same year, Spain bought 18.4% of its total cereals purchased on foreign markets from Ukraine, valued at EUR 545 million. This makes Ukraine its second biggest trade partner after Brazil. In the case of corn, an essential item for animal feed, Ukraine accounted for more than 30% of total imports, accounting for 2.4 million tons worth EUR 510 million [75].

3.1.2. Accessibility

This pillar comprises variables that measure infrastructures for bringing food to market, individual indicators of people’s access to calories, and affordability of purchasing nutritional food. Accordingly, market disruption and rising inflation may put the food accessibility pillar in jeopardy [55]. Due to the Ukraine–Russia war, it will become even more difficult for some European low-income households to afford food.

As explained above, the food supply in the EU is not jeopardized since most European countries benefit from well-developed agricultural production. Indeed, the EU is a significant producer of agri-food products—it was the world’s largest trader in 2021—and, although Russia’s conflict in Ukraine and climate change affect output, the EU’s food system remains robust and reliable. However, inflation and increased food prices affect EU citizens [76]. The steep rise in energy prices following the conflict impacts agriculture, an energy-intensive industry. Additionally, despite the recent price drops, the cost of fertilizers and other energy-intensive goods has remained high due to the war. Increased input costs translate into higher production expenses, thus raising food prices [23]. Accordingly, accessibility and affordability are the main consequences of the conflict on food security, especially for low-income and vulnerable populations that are disproportionately impacted [76].

On average, Europeans face lower rates of undernourishment, hunger, and food insecurity than the rest of the world [77]. However, in 2021, 7.3% of the EU’s total population and more than one-sixth of the poor could not afford a meal containing meat, fish, or a vegetarian equivalent every other day. This proportion varied from 22.4% in Bulgaria to less than 2.0% in Cyprus (0.4%), Ireland (1.6%), Sweden (1.6%), and the Netherlands (1.8%). Among those at risk of poverty, the share was 17.4% [78].

According to Eurostat [79], the European Union’s statistics agency, annual inflation in the Eurozone is predicted to be 9.2% in December 2022, down from 10.1% in November. When it comes to the main components of eurozone inflation, energy is expected to have the highest annual rate in December (25.7% compared with 34.9% in November), followed by food, alcohol, and tobacco (13.8% compared with 13.6% in November), and non-energy industrial goods (6.4% compared with 6.1% in November). It dipped slightly lower for the first time since June 2021. However, it remains in the double digits as increasing food costs and hefty energy bills continue to strain budgets. They will continue to have an impact on European consumers’ purchasing power.

Since November 2021, energy and food have been the primary contributors to consistently high monthly inflation. Since the Spring of 2022, the situation has deteriorated due to market interruptions caused by the conflict in Ukraine. The Baltic countries continue to be the most affected. For instance, in November 2022, inflation in Latvia was at 21.7% compared with 7.4% a year ago, making it the highest rate in the Eurozone. Inflation in the UK unexpectedly climbed to 11.1% in October 2022, the highest level since 1981. Despite a government cap, the cost of energy and gas increased by 24% year over year, while the price of food increased by 16.4%, contributing significantly to the overall rise [80]. Even though inflation affects countries differently throughout the EU, lower-income families are the most impacted in all member states. According to the European Parliament’s Eurobarometer study [81], the major concern for European citizens is “increasing living costs” (93%), followed by “poverty and social exclusion” (82%).

Moreover, inflation caused by the conflict might cut private consumption by 1.1% in the European Union in 2022. However, the effect would vary by country. The impact will be felt more acutely in nations where consumption is more sensitive to energy and food costs and where a sizable proportion of the population is vulnerable to poverty. Central and south-eastern European countries are disproportionately impacted [82]. Europeans continuously feel the strain of the rise in food prices and the high inflation rate. As a result, many European citizens are losing buying power of necessary commodities. For instance, even Germany, which has solid domestic production and does not rely much on Ukrainian exports, is very susceptible to escalating inflation, driven mainly by the rising cost of Russian energy and fertilizer [29]. In November 2022, Germany’s consumer price index (CPI) year-over-year change was 10.0%. This was a modest decrease in the inflation rate from the +10.4% seen in October 2022. In November 2022, food prices increased by 21.1% compared with November 2021. This inflation rate is more than twice as high as the rate of general price inflation. The annual rate of inflation for food has been steadily climbing since January (October 2022: +20.3%). In November of 2022, prices increased across the board for all types of food. Edible fats and oils had the most significant price increase at 41.5%; dairy products and eggs increased by 34.0%; bread and cereals increased by 21.1%; vegetables increased by 21.1% [83] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Consumer price indices in Germany (2015 = 100). Source: German Federal Statistical Office [83].

In Spain, cereals and animal feed supply shortages from Ukraine directly impact producer pricing as the production of pigs is heavily reliant on grains and corn supplied from Ukraine. In this industry, inflation is also harming livestock farmers’ profitability. Although producers attempt to agree with shops to decrease finished items’ prices, meat prices will undoubtedly rise due to import constraints of wheat and corn finished items’ prices and meat prices will undoubtedly rise due to import constraints of wheat and corn [29].

For instance, Hungary is emerging as a new inflation hotspot due to the highest food price hikes among the EU’s member states [84]. Despite producing most of the grain supplies it needs domestically, Hungary imports little wheat from Russia or Ukraine. However, the disruption in global value chains is reflected in increased food prices. Further, similar to other EU nations, Hungary is impacted by fertilizer supply problems caused by halted exports from Russia, the world’s largest supplier. This situation is exacerbated by businesses’ difficulties in sustaining their production capabilities as energy costs climb [29]. Accordingly, during November 2022, food price increases were 40% more than the EU average. Bread, cheese, and eggs have all seen price increases of over 90% from the same time in 2021, with egg costs increasing by over 92%. Consequently, the government has indicated it would add eggs and potatoes to the list of five items for which price controls will be implemented [84].

The persistent and significant uncertainty surrounding the ongoing high inflation raises the question of how these affect European households’ finances, purchasing power, and socio-economic situation. Rising energy and food prices are already generating high societal costs in terms of decreased buying power and are anticipated to exacerbate material deprivation, poverty, and social exclusion throughout the EU [31]. It is estimated that in 2021, 95.4 million people in the EU (21.7% of the population) were vulnerable to poverty or social exclusion (livelihood poverty, extreme material and social deprivation, or living in a household with low labor intensity) [85]. The ongoing inflation imposes significant welfare and social costs on European society. The socio-economic ramifications of the current situation are notably unequal throughout the EU, owing to considerable disparities in price trends and spending patterns among member states and demographic divisions. Prospects are especially bleak in several central and eastern European nations, where low-income families and vulnerable groups (such as large households, rural populations, children, and the elderly) face heightened financial difficulty and social exclusion risks. At the EU level, inflation has raised the cost of living for median families by around 10%, the incidence of material and social deprivation by approximately 2%, and the rate of energy poverty and absolute monetary poverty by about 5%. The related welfare consequences are predicted to be several times greater in selected member states and among vulnerable populations, presumably widening existing inequalities in poverty and social exclusion throughout the EU [31].

Consequently, food bank use is rising throughout Europe, as the region’s poorest, who spend a more significant percentage of their income on energy and food, are struck the hardest by the region’s most tremendous inflation in a generation. Charities from Spain to Latvia estimate a 20% to 30% rise in demand over last year, with a further increase expected this winter. People accessing the national food bank in Bulgaria, one of the poorest nations in the EU, increased by three-quarters between September and October 2022 [86]. However, in many countries, the organizations that manage the food banks face increased operational expenses, which endangers their operations. For instance, food banks in Germany are busier than ever, with empty shelves, high pricing, and more people in need. There is also a scarcity of donations and volunteers [87]. In the UK, donations to food banks are declining due to rising living costs, but demand increases as inflation continues to increase and people have difficulty buying vital food products. Amid a cost-of-living crisis, when more than a quarter of all UK households report struggling financially, families’ priorities are saving money for food shopping needs. Contrarily, more than half of food bank donations have dropped [88,89]. Furthermore, people oppose cost-of-living raises using various means, including street protests and strikes, in several nations [90].

3.1.3. Utilization

This pillar tracks anthropometric and other measures of people’s ability to use calories; related measures include wasting, stunting, and low weight among children. Russia’s war in Ukraine harmed the food utilization pillar, resulting in a lack of nutritional variety and malnutrition.

In addition to the 780 to 811 million people who experienced chronic hunger in 2020, FAO predicts that, in 2022 and 2023, there will be an additional 7.6 million to 13.1 million undernourished people due to Russia’s war in Ukraine [18]. The nutritional variety substantially impacts EU citizens’ health [26]. Since healthy variety or dietary diversity is a fundamental requirement for people to obtain all essential nutrients, it can be used as one of the core indicators for examining food habits and the productivity of people. Hence, chronic hunger in the EU is associated with undernourishment, indicative of a productivity decline.

3.1.4. Stability

When the previous three pillars are in order, this pillar ensures the stability of supply and access over time [91]. The main issues impeding the stability pillar of food security are higher energy prices, rising interest rates, and political turmoil. As a result of higher food and energy prices, farmers from competing nations, such as the United States and Brazil, may cover any supply shortages created by the war in Ukraine. However, higher energy prices make some food products, mainly corn, sugar, and oilseeds/vegetable oils, more appealing for bioenergy production, such as ethanol or biodiesel. This could raise food prices to their energy parity equivalents [23].

Meanwhile, the increased costs and shortages will significantly impact food assistance for vulnerable nations. According to estimates from the World Food Program (WFP) [92], 45% of the population in Ukraine is already concerned about having enough to eat. Furthermore, higher and unstable energy prices were also observed, particularly for natural gas, which is essential for fertilizer production [93]. Due to several factors, including weather-related interruptions to the supply of coal and renewable energy, prices have been increasing significantly since 2021 [7].

Since the outbreak of the Ukrainian conflict, Europe’s economic growth forecasts have been lowered downward, while inflation forecasts have risen. Most current predictions, which account for increased uncertainty and commodity price shocks, indicate that real GDP growth in the European Union might fall far below 3% in 2022, a drop of more than 1.3 percentage points from pre-war expectations. Additional supply chain disruptions and economic penalties are expected to send the European economy into a recession [82]. There has already been a substantial economic impact on European consumers due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, posing political risks to incumbent governments. Rising inflation, higher food prices, and food insecurity result in protests and strikes across Europe, underscoring growing discontent with skyrocketing living costs and threatening political turmoil.

As of January 2023, the slowdown in the global economy and fears of a worldwide recession have contributed to a general lowering of commodity prices. Nevertheless, commodity prices remain high relative to historical averages, extending the challenges connected with food security. Lower input costs, especially for fertilizers, are expected to contribute to a 5% drop in agricultural prices in 2023. Despite these forecasts, prices are projected to stay higher than pre-pandemic levels. As a result, global inflation will remain high in 2023 at 5.2% before decreasing to 3.2% in 2024. Although inflation is expected to decline gradually during 2023, underlying inflationary pressures may become more persistent [25]. According to the International Monetary Fund [94], global food prices are anticipated to stay high due to conflict, energy costs, and weather events, despite interest rate rises marginally easing pricing pressures.

Although the European Central Bank has increased interest rates to combat inflation, it also anticipates that consumer prices will rise further. Additionally, the depreciation of the euro and the pound versus the US dollar has placed further pressure on manufacturers and merchants who must pay their suppliers in US dollars and numerous nations are now facing a possible recession [90].

3.2. Reshaping EU Food Security Amid the War Crisis

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the European Parliament adopted a comprehensive resolution on 24 March 2022, endorsing many of the initiatives included in the European Commission’s package and calling for an urgent EU action plan to secure food security both inside and outside the EU [95]. EU leaders endorsed short-term and medium-term measures at the state levels to protect food security and strengthen the resilience of food systems. Most actions may be carried out using the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP). The EU members emphasized the importance of maintaining food supply security and took some immediate actions (Box 1).

Box 1. Prompt action from the European Union to maintain food safety and build a resilient food system [96,97,98,99].

● EU farmers support a package worth EUR 500 million to safeguard food security and strengthen the resilience of food systems.

● Reduction of energy import dependency and price shocks through REPowerEU plans.

● Maintaining the EU single market by avoiding restrictions and bans on exports.

● The Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD) provides food and essential material support worth EUR 3.8 billion.

● Using the new CAP strategic plans to decrease reliance on gas, fuel, and inputs such as pesticides and fertilizers.

● A unique and temporary exception to enable the cultivation of any crops for food and feed on fallow land while farmers retain the full amount of the greening payment.

● Specific temporary exemptions from current animal feed import regulations.

Sources: [96,97,98,99]

The conflict is pushing food security challenges to the brink of a global crisis. As the war continues, several scenarios could affect food security in the EU. The EU food system is typically vulnerable due to fertilizer import dependency, unreliable grain markets, and high energy prices. In addition, these factors further exacerbated food insecurity during the war [100].

Further strategies are needed to safeguard food security and bring resilience to the food system. The war has exposed the global food system’s fragility, emphasizing the significance of rebuilding the food system to strengthen resilience to future shocks, crises, and stressors [101]. As shown in Figure 5, several approaches are required, such as increasing food aid, ensuring fertilizer supply, imposing an energy price cap, initiating a farmer support package, switching to renewable energy sources for cultivation, changing individual food behaviors, lifting a trade ban, and political stability.

Figure 5.

Actions for ensuring food security and strengthening food system resilience. Source: developed by authors.

The food availability pillar has been jeopardized during Russia’s armed confrontation with Ukraine. As a result, the EU needs enough fertilizer at a reasonable price to make agricultural production more efficient to safeguard the food availability pillar. Maintaining equity in fertilizer access is a powerful lever for reducing food insecurity concerns in the short term. In the longer term, fair fertilizer usage must be supplemented with efforts to guarantee sustainable fertilizer use, ecosystem protection, and emission reductions [102]. However, export restrictions and bans must be avoided to preserve the EU single market. This will allow the EU and vulnerable countries to maintain a secure food supply.

Food insecurity is the inability to consistently obtain adequate food to maintain an active and healthy lifestyle. On the contrary, food security can be established only through easy access to food, which the war has already impacted. The EU member states should impose a price cap on food to prevent adverse effects from market anomalies. Consequently, food would be more affordable and accessible to the EU people. In addition, the government needs to increase food aid to support the most vulnerable citizens in the EU. Furthermore, price caps can reduce inflation rates in the EU, which can promote food accessibility.

Several measures can be taken to ensure food utilization, including minimizing food waste and loss, eating a healthy diet, or recycling food. Foods derived from plants are transformed into culinary creations that satisfy hunger, provide nutrients, and alleviate obesity. Indeed, adopting plant-based diets across Europe may boost food resilience in the face of the Russia–Ukraine war [27].

Households must always have access to adequate food to be food secure. In case of a sudden shock, such as a climatic or economic crisis or a war, they should not risk losing access to food. The armed conflict involving Russia in Ukraine impacts food stability in the EU and beyond. This situation requires a reduction in the interest rate to reduce food import prices and a reduction in Value-Added Tax (VAT), which is an alternative solution. Energy price caps protect consumers who default on basic energy tariffs from their suppliers. Putting a cap on energy prices ensures that businesses and individuals will pay a fair price, limiting food inflation, import costs, and retail prices.

The significant trade-related impact of the war causes an increase in commodity prices. Indeed, energy, food products, and metals are three major commodities impacted by the war. Consequently, the significant price hike affects global markets and supply chains. Furthermore, commodity price hikes coupled with higher inflation rates on a global scale could result in changes in demand because people are unable or unwilling to make the usual food purchases.

In the context of the Russia–Ukraine war, to enhance the resilience of food systems against future crises, we have outlined five key initiatives that will help global policymakers, governments, and researchers to minimize the impact of food insecurity in the EU:

- Food prices will rise due to higher energy costs since fertilizers and transportation costs will also increase. As a result, renewable energy sources must be adopted by EU farmers to lower the cost of agricultural output.

- The governments in the EU should impose an energy price cap to stagnate price volatility. For instance, the Hungarian government has set energy and food price caps amid soaring inflation.

- Monetary policy should remain on track to restore price stability, while fiscal policy should strive to reduce cost-of-living pressures while remaining appropriately restrictive in line with monetary policy [31].

- The war might also cause further disruptions to global supply chains, making international trade even more challenging. Export restrictions and bans should be avoided to preserve the EU single market.

- The war may have political repercussions as well. For instance, increased energy costs could result in instability and violence in society and politics. Therefore, EU leaders must provide adequate food aid to their citizens.

Furthermore, in the short term, measures aimed at preserving and expanding trade routes from Ukraine, enabling greater food production in vulnerable countries, and reducing harmful consumption in the EU are most adapted to addressing the present issues. Although, the food crisis causes immediate concerns, it also highlights systemic issues in the European and global food systems. As highlighted by Galanakis [14] “The pressing challenges induced by climate change, global warming, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russian-Ukrainian war merge to conclude that the food sector needs an urgent transformation toward sustainability and resilience.”

While short-term solutions may mitigate the crisis’ negative effect, a long-term and systemic approach is required to strengthen its resilience [102]. As the European Commission [103] outlined, improving resilience through minimizing European agriculture’s reliance on energy, energy-intensive imports, and feed imports is more critical than ever. Resilience necessitates diverse import sources and market outlets through a solid global and bilateral trade strategy. Consequently, the Commission has asked member states to consider revising their Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) strategic plans to boost the sector’s resilience, increase renewable energy output, and decrease reliance on synthetic fertilizers via more sustainable production methods [103]. Overall, addressing food security challenges in Europe requires a comprehensive approach that involves improving domestic food production, reducing dependence on food imports, reducing food waste, shifting to more sustainable diets, and increasing international cooperation while diversifying trade partnerships.

4. Conclusions

Food systems in Europe are facing several environmental, economic, social, and health issues. Research that straddles disciplines and innovates at their intersections is required to effectively address them. This paper aimed to assess the possible impacts of the war between Russia and Ukraine on food security in European countries. The review suggests that the implications of war varied among the food security pillars. However, the prolonged repercussions of the Russian–Ukraine conflict on fertilizer prices will influence domestic food production by making fertilizers less available and more expensive. As energy costs and interest rates in the EU continue to climb, food importers will find it considerably more challenging to fund the cost of food imports, affecting domestic food prices and, consequently, food accessibility and affordability across the EU. The impacts on food availability and accessibility can have long-term implications regarding food use (e.g., dietary diversity) and food system stability and resilience. Indeed, high inflation, trade restrictions, food price hikes, shortages of fertilizer, and political turmoil can directly impact the EU’s food security pillars.

The paper contributed to the literature on food security and the war effect by shedding light on the following facts: (1) lack of fertilizer supplies (determining their price increases), higher energy prices, trade restrictions, and bans, as well as rising inflation rates increase food prices and affect the availability and accessibility of food; (2) increasing food price caps and food aid and limiting the inflation rate can improve food accessibility; (3) it is possible to protect the food utilization pillar by eating a nutritious diet, diversifying diet, and promoting food recovery and distribution; (4) social and political unrest and turmoil can be controlled by lowering interest rates and imposing energy price caps, which secure food stability pillar.

Further, by adopting a comprehensive analytical approach that considers all four dimensions of food security, this research has provided a thorough understanding of how the prolonged Russian–Ukrainian conflict has affected food security in Europe. By assessing the various drivers and factors contributing to food insecurity, the study has identified the key challenges facing the food systems in Europe. Furthermore, addressing these complex challenges requires innovative interdisciplinary research that straddles the boundaries of different disciplines and innovates at their intersections. This approach can lead to new knowledge, solutions, and strategies that can help to ensure the sustainability, resilience, and inclusivity of the food systems in Europe. Moreover, the impact of the conflict on food security may vary across different regions and countries in Europe, depending on their level of dependence on agricultural imports, their capacity to produce food locally, and their vulnerability to food price shocks. This variability adds to the uncertainty in predicting the impact of the conflict on food security in Europe.

Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of developing effective and efficient policy solutions based on a shared understanding of the complex and interconnected nature of Europe’s food security concerns in the context of the war. This might include adopting a unified strategy for data collection, analysis, and sharing, as well as enacting policy actions adapted to the individual requirements of the impacted regions and individuals. This study contributes to the theoretical development of policies that promote sustainable and resilient food systems, especially in the face of prolonged wars and other geopolitical issues, by emphasizing the need for inter-European collaboration.

This paper does have some limitations. One of the main limitations is the high level of uncertainty, since the impacts of the war depend not only on the evolution of the conflict but also on the responses of the EU and single member states. Russia’s current approach to the conflict in Ukraine will likely prolong the war over the next few years and Europe’s ability to survive a food crisis will be pushed to its limits. The EU will have a more robust long-term stance toward Russia if it can continue to be united and successfully coordinated. Although we have suggested risk-reduction methods, resolving the situation would necessitate a thorough re-assessment of the EU’s food security and agri-food systems over the following years.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.R. and T.B.H.; methodology, M.F.R., T.B.H., H.E.B. and A.R.; validation, M.F.R.; formal analysis, M.F.R., H.E.B. and A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.R., T.B.H. and H.E.B.; writing—review and editing, M.F.R., T.B.H., H.E.B., A.R. and D.R.; visualization, M.F.R.; supervision, H.E.B. and A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vos, R.; Glauber, J.; Hernández, M.; Laborde, D. COVID-19 and Rising Global Food Prices: What’s Really Happening? Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/covid-19-and-rising-global-food-prices-whats-really-happening (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Rice, B.; Hernández, M.A.; Glauber, J.; Vos, R. The Russia-Ukraine War Is Exacerbating International Food Price Volatility. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/russia-ukraine-war-exacerbating-international-food-price-volatility (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- NASA. Brazil Battered by Drought. Available online: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148468/brazil-battered-by-drought (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Glauber, J.; Laborde, D. How Will Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Affect Global Food Security? Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-will-russias-invasion-ukraine-affect-global-food-security (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- European Parliament Question Time: Food Price Inflation in Europe. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2023/739298/EPRS_ATA(2023)739298_EN.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- FAO. Impact of the Ukraine-Russia Conflict on Global Food Security and Related Matters under the Mandate of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ni734en/ni734en.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Pereira, P.; Zhao, W.; Symochko, L.; Inacio, M.; Bogunovic, I.; Barcelo, D. The Russian-Ukrainian Armed Conflict Will Push Back the Sustainable Development Goals. Geogr. Sustain. 2022, 3, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston Consulting Group. The War in Ukraine and the Rush to Feed the World. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/how-the-war-in-ukraine-is-affecting-global-food-systems (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- KPMG. Ukraine-Russia Sector Considerations: Agriculture. Available online: https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2022/05/ukraine-russia-sector-considerations-agriculture.html (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Jagtap, S.; Trollman, H.; Trollman, F.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Parra-López, C.; Duong, L.; Martindale, W.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Hdaifeh, A.; et al. The Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Its Implications for the Global Food Supply Chains. Foods 2022, 11, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Hassen, T.; el Bilali, H. Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine War on Global Food Security: Towards More Sustainable and Resilient Food Systems? Foods 2022, 11, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloem, J.R.; Farris, J. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Food Security in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Review. Agric. Food Secur. 2022, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanakis, C.M. The “Vertigo” of the Food Sector within the Triangle of Climate Change, the Post-Pandemic World, and the Russian-Ukrainian War. Foods 2023, 12, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreign Affairs No One Would Win a Long War in Ukraine. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/no-one-would-win-long-war-ukraine (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Allam, Z.; Bibri, S.E.; Sharpe, S.A. The Rising Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Russia–Ukraine War: Energy Transition, Climate Justice, Global Inequality, and Supply Chain Disruption. Resources 2022, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-Y.; Lu, G.; Xu, Z.; Yan, X.; Khu, S.-T.; Yang, J.; Zhao, J. Influence of Russia-Ukraine War on the Global Energy and Food Security. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Safeguarding Food Security and Reinforcing the Resilience of Food Systems; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The Importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for Global Agricultural Markets and the Risks Associated with the Current Conflict. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb9013en/cb9013en.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- OECD. Economic and Social Impacts and Policy Implications of the War in Ukraine. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/4181d61b-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/4181d61b-en (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Rabobank. The Russia-Ukraine War’s Impact on Global Fertilizer Markets. Available online: https://research.rabobank.com/far/en/sectors/farm-inputs/the-russia-ukraine-war-impact-on-global-fertilizer-markets.html (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Benton, T.; Froggatt, A.; Wellesley, L.; Grafham, O.; King, R.; Morisetti, N.; Nixey, J.; Schröder, P. The Ukraine War and Threats to Food and Energy Security: Cascading Risks from Rising Prices and Supply Disruptions. Available online: https://chathamhouse.soutron.net/Portal/Public/en-GB/RecordView/Index/191102 (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- FAO. The Importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for Global Agricultural Markets and the Risks Associated with the War in Ukraine. December 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cc3317en/cc3317en.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Hellegers, P. Food Security Vulnerability Due to Trade Dependencies on Russia and Ukraine. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Food Security Update. January 2023. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-update (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- World Bank Food Security Update. December 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-update?cid=ECR_LI_worldbank_EN_EXT (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Sun, Z.; Scherer, L.; Zhang, Q.; Behrens, P. Adoption of Plant-Based Diets across Europe Can Improve Food Resilience against the Russia–Ukraine Conflict. Nat. Food. 2022, 3, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Commission. Acts for Global Food Security and for Supporting EU Farmers and Consumers. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_1963 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- European Committee of the Regions Repercussions of the Agri-Food Crisis at Local and Regional Level. Available online: http://www.cor.europa.eu (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Tollefson, J. What the War in Ukraine Means for Energy, Climate and Food. Nature 2022, 604, 232–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menyhert, B. The Effect of Rising Energy and Consumer Prices on Household Finances, Poverty and Social Exclusion in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. World Economic Outlook, October 2022: Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2022/10/11/world-economic-outlook-october-2022 (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Lang, T.; McKee, M. The Reinvasion of Ukraine Threatens Global Food Supplies. BMJ 2022, 376, o676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osendarp, S.; Verburg, G.; Bhutta, Z.; Black, R.E.; de Pee, S.; Fabrizio, C.; Headey, D.; Heidkamp, R.; Laborde, D.; Ruel, M.T. Act Now before Ukraine War Plunges Millions into Malnutrition. Nature 2022, 604, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nóia Júnior, R.d.S.; Ewert, F.; Webber, H.; Martre, P.; Hertel, T.W.; van Ittersum, M.K.; Asseng, S. Needed Global Wheat Stock and Crop Management in Response to the War in Ukraine. Glob. Food Sec. 2022, 35, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Li, X.; Jia, N.; Feng, F.; Huang, H.; Huang, J.; Fan, S.; Ciais, P.; Song, X.-P. The Impact of Russia-Ukraine Conflict on Global Food Security. Glob. Food Sec. 2023, 36, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuk, P.; Żuk, P. National Energy Security or Acceleration of Transition? Energy Policy after the War in Ukraine. Joule 2022, 6, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, R.E.; Wasum, D. Russian-Ukraine 2022 War: A Review of the Economic Impact of Russian-Ukraine Crisis on the USA, UK, Canada, and Europe. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2022, 9, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, I.; Patel, R.; Yarovaya, L. The Reaction of G20+ Stock Markets to the Russia–Ukraine Conflict “Black-Swan” Event: Evidence from Event Study Approach. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2022, 35, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidi, M. Caught off Guard and Beaten: The Ukraine War and Food Security in the Middle East. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchasi, G.; Mwasha, C.; Shaban, M.M.; Rwegasira, R.; Mallilah, B.; Chesco, J.; Volkova, A.; Mahmoud, A. Ukraine’s Triple Emergency: Food Crisis amid Conflicts and COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.; Martin-Moreno, J. ASPHER Statement: 5 + 5 + 5 Points for Improving Food Security in the Context of the Russia-Ukraine War. An Opportunity Arising from the Disaster? Public Health Rev. 2022, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Krieg Produziert Hunger. Osteuropa 2022, 72, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine and Critical Agrarian Studies. J. Peasant Stud. 2023, 50, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatab, A.A. Africa’s Food Security under the Shadow of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Strateg. Rev. South. Afr. 2022, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M. Global Food Security Hit by War. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R341–R343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnassi, M.; el Haiba, M. Implications of the Russia–Ukraine War for Global Food Security. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine–Implications for Grain Markets and Food Security. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lyu, D.; Sun, K.; Li, S.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, R.; Zheng, M.; Song, K. Spatiotemporal Analysis and War Impact Assessment of Agricultural Land in Ukraine Using RS and GIS Technology. Land 2022, 11, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, V.J.P.D. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Russia–Ukraine Conflict on Land Use across the World. Land 2022, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.A.; Nugroho, A.D.; Lakner, Z. Impact of the Russian–Ukrainian Conflict on Global Food Crops. Foods 2022, 11, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazbeck, N.; Mansour, R.; Salame, H.; Chahine, N.B.; Hoteit, M. The Ukraine–Russia War Is Deepening Food Insecurity, Unhealthy Dietary Patterns and the Lack of Dietary Diversity in Lebanon: Prevalence, Correlates and Findings from a National Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, A.R.; Donovan, J.; Sonder, K.; Baudron, F.; Lewis, J.M.; Voss, R.; Rutsaert, P.; Poole, N.; Kamoun, S.; Saunders, D.G.O.; et al. Near- to Long-Term Measures to Stabilize Global Wheat Supplies and Food Security. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriquiry, M.; Dumortier, J.; Elobeid, A. Trade Scenarios Compensating for Halted Wheat and Maize Exports from Russia and Ukraine Increase Carbon Emissions without Easing Food Insecurity. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Bašić, F.; Bogunovic, I.; Barcelo, D. Russian-Ukrainian War Impacts the Total Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 837, 155865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN High Level Task Force on Global Food Security. Food and Nutrition Security: Comprehensive Framework for Action. Summary of the Updated Comprehensive Framework for Action (UCFA); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- de Paulo Gewehr, L.L.; de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O. Geopolitics of Hunger: Geopolitics, Human Security and Fragile States. Geoforum 2022, 137, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Shields, C.P.; Stojetz, W. Food Security and Conflict: Empirical Challenges and Future Opportunities for Research and Policy Making on Food Security and Conflict. World Dev. 2019, 119, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Ukraine: Strategic Priorities for 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/fr/c/CC3385EN/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- USDA. Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus–Crop Production Maps. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/rssiws/al/up_cropprod.aspx (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- The New York Times. Mines, Fires, Rockets: The Ravages of War Bedevil Ukraine’s Farmers. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/04/world/europe/ukraine-russia-farms-farming-wheat-barley.html (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Bin-Nashwan, S.A.; Hassan, M.K.; Muneeza, A. Russia–Ukraine Conflict: 2030 Agenda for SDGs Hangs in the Balance. Int. J. Ethics. Syst. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO FAOSTAT. Ukraine. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#country/230 (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Bokusheva, R.; Hockmann, H.; Kumbhakar, S.C. Dynamics of Productivity and Technical Efficiency in Russian Agriculture. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2012, 39, 611–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshchenko, R. Ukraine Can Feed the World. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/ukraine-can-feed-the-world/ (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- AMIS. Market Monitor May 2022. Available online: http://www.amis-outlook.org/fileadmin/user_upload/amis/docs/Market_monitor/AMIS_Market_Monitor_current.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Laborde, D.; Glauber, J. Suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative: What Has the Deal Achieved, and What Happens Now? Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/suspension-black-sea-grain-initiative-what-has-deal-achieved-and-what-happens-now (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Knowledge Centre for Global Food and Nutrition Security. The Impact of Russia’s War against Ukraine on Global Food Security-Impact on Global Agricultural Production and Exports Impact on Ukrainian Production and Exports. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Impact%20of%20Russia%20war%20against%20Ukraine%20on%20global%20food%20security_knowledge%20review%206_final.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Reuters Ukraine Farmers May Cut Winter Grain Sowing by at Least 30%–Union. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-grain-sowing-idAFL1N30J0CL (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- The New York Times. How Russia’s War on Ukraine Is Worsening Global Starvation. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/02/us/politics/russia-ukraine-food-crisis.html (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Glauber, J.; Laborde, D.; Mamun, A. From Bad to Worse: How Russia-Ukraine War-Related Export Restrictions Exacerbate Global Food Insecurity. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/bad-worse-how-export-restrictions-exacerbate-global-food-security (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Glauber, J.; Laborde, D.; Mamun, A. Food Export Restrictions Have Eased as the Russia-Ukraine War Continues, but Concerns Remain for Key Commodities. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/food-export-restrictions-have-eased-russia-ukraine-war-continues-concerns-remain-key (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Food Security Portal Food and Fertilizer Export Restrictions Tracker. Available online: https://www.foodsecurityportal.org/tools/COVID-19-food-trade-policy-tracker (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Soffiantini, G. Food Insecurity and Political Instability during the Arab Spring. Glob. Food Sec. 2020, 26, 100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, P.; Bergevoet, R.; van Berkum, S. A Brief Analysis of the Impact of the War in Ukraine on Food Security. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/596254 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Agroberichten Buitenland. Ukraine Is a Key Supplier of Some Commodities to Spain. Available online: https://www.agroberichtenbuitenland.nl/actueel/nieuws/2022/03/15/ukraine-is-a-key-supplier-of-some-commodities-to-spain (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- European Council Food Security and Affordability. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/food-security-and-affordability/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- FAO. Europe and Central Asia–Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2021; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Living Conditions in Europe–Material Deprivation and Economic Strain. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Living_conditions_in_Europe_-_material_deprivation_and_economic_strain#Key_findings (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Eurostat Euro Area Annual Inflation Down to 9.2%. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/15725146/2-06012023-AP-EN.pdf/885ac2bb-b676-0f0d-b8b1-dc78f2b34735 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Euronews Eurozone Inflation Is Easing but Remains Painful. Which Countries in Europe Are Being Worst Hit? Available online: https://www.euronews.com/next/2022/11/30/record-inflation-which-country-in-europe-has-been-worst-hit-and-how-do-they-compare (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Parliament EP Autumn 2022 Survey: Parlemeter. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2932 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- European Investment Bank. How Bad Is the Ukraine War for the European Recovery? Available online: www.eib.org/economics (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- German Federal Statistical Office Inflation Rate at +10.0% in November 2022. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2022/12/PE22_529_611.html (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Bloomberg Hungary Becomes EU’s New Inflation Hotspot as Food Prices Spiral. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-08/hungary-becomes-eu-s-new-inflation-hotspot-as-food-prices-spiral?leadSource=uverify%20wall (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Eurostat Over 1 in 5 at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20220915-1 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Financial Times on the Breadline: Inflation Overwhelms Europe’s Food Banks. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/bb098ccd-c74b-4c7e-8baa-e90546030fa5 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Deutsche Welle Niemcy: Bankom Żywności Kończą Się Zapasy. Available online: https://www.dw.com/pl/niemcy-bankom-%C5%BCywno%C5%9Bci-ko%C5%84cz%C4%85-si%C4%99-zapasy/a-61712630 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Grocery Gazette Special Report: How the Cost-of-Living Crisis Is Affecting Supermarket Food Bank Donations. Available online: https://www.grocerygazette.co.uk/2022/12/12/supermarket-food-bank-donation/ (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- The Guardian Food Bank Britain: Five Months on the Frontline of the New Emergency Service. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/dec/03/food-bank-britain-five-months-on-the-frontline-of-the-new-emergency-service (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- McKinsey & Company. How Retailers in Europe Can Navigate Rising Inflation. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/how-retailers-in-europe-can-navigate-rising-inflation (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Aborisade, B.; Bach, C. Assessing the Pillars of Sustainable Food Security. Eur. Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2014, 3, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. WFP Reaches One Million People with Life-Saving Food Support in Conflict-Stricken Ukraine. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/news/wfp-reaches-one-million-people-life-saving-food-support-conflict-stricken-ukraine (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Rabbi, M.F.; Popp, J.; Máté, D.; Kovács, S. Energy Security and Energy Transition to Achieve Carbon Neutrality. Energy 2022, 15, 8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. Global Food Prices to Remain Elevated Amid War, Costly Energy, La Niña. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/12/09/global-food-prices-to-remain-elevated-amid-war-costly-energy-la-nina (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- European Parliament Need for an Urgent EU Action Plan to Ensure Food Security inside and Outside the EU in Light of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0099_EN.html (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- European Commission Increased Support for EU Farmers through Rural Development Funds. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_3170 (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- European Commission REPowerEU: Affordable, Secure and Sustainable Energy for Europe. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/repowereu-affordable-secure-and-sustainable-energy-europe_en (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission Diverse Approaches to Supporting Europe’s Most Deprived: FEAD Case Studies 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/european-social-fund-plus/en/publications/2021-fead-network-case-study-catalogue (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- European Commission CAP Strategic Plans and Commission Observations. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/cap-my-country/cap-strategic-plans_en (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- McKinsey & Company. A Reflection on Global Food Security Challenges Amid the War in Ukraine and the Early Impact of Climate Change. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/agriculture/our-insights/a-reflection-on-global-food-security-challenges-amid-the-war-in-ukraine-and-the-early-impact-of-climate-change (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Dyson, E.; Helbig, R.; Avermaete, T.; Halliwell, K.; Calder, P.C.; Brown, L.R.; Ingram, J.; Popping, B.; Verhagen, H.; Boobis, A.R.; et al. Impacts of the Ukraine–Russia Conflict on the Global Food Supply Chain and Building Future Resilience. EuroChoices 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachmann, G.; Weil, P.; von Cramon-Taubadel, S. A European Policy Mix to Address Food Insecurity Linked to Russia’s War. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/european-policy-mix-address-food-insecurity-linked-russias-war#toc-2-2-effects-on-prices (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- European Commission. New Common Agricultural Policy: Set for 1 January 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_7639 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |