1. Introduction

Employees face rising levels of stress, anxiety, and burnout across industries, citing work as the primary contributor [

1,

2]. Outside of work, loneliness and isolation are on the rise [

3], and individuals are experiencing greater mental health challenges than prior generations [

4]. This individual suffering cannot be isolated from work. Organizational life is inherently emotional [

5] and regardless of the source of one’s suffering, it will inevitably spill into the workplace. Taken collectively, widespread suffering, stemming from individual and organizational factors, is pervasive within organizations. This suffering, if not addressed appropriately, has the potential to threaten the sustainability of employees and, eventually, organizations.

One method for moving toward more sustainable workplaces is cultivating compassion. Compassion—when one is moved to alleviate the suffering of another [

6]—has been linked to a variety of positive outcomes. Compassion helps the individual sufferer, as it helps the sufferer cope [

6], supports one’s ability to process grief [

7,

8], and conveys dignity to the sufferer [

9]. Compassion also has a positive impact on relationships and organizations. At the relational level, compassion can support a sense of connection with others [

10] and a sense of personal satisfaction and pride [

11]. Organizationally, these positive emotions can lead to a greater sense of commitment to the organization, increased collaboration, and greater prosocial motivation to help others [

9].

Despite these positive benefits, compassion scholars remain puzzled as to the primary inhibitors of compassion at work. While several scholars have established theories that advance our understanding of the compassion sub-processes [

12,

13,

14,

15] and the contextual factors that influence those sub-processes [

9,

16], compassion theorizing has yet to adequately explain why compassion so often fails to unfold within organizational contexts. As such, the existing body of compassion work has been critiqued as overly idealistic [

17].

The purpose of this paper is to extend our understanding of compassion theory by exploring a major limitation of the current research—the lack of understanding regarding how suffering employees make sense of disclosing and discussing suffering at work. Recent theoretical work suggests that sufferer uncertainty around disclosing suffering at work may be a key inhibitor of compassion [

16], but to date, most compassion research has explored how compassion providers make sense of compassion processes [

6,

14,

15] and thus have obscured the perspective of suffering employees. Given that compassion is an inherently relational process [

15], driven by both individuals’ respective sensemaking [

9], it is critical to understand how sufferers make sense of their decision to disclose suffering at work and engage others across the compassion sub-processes.

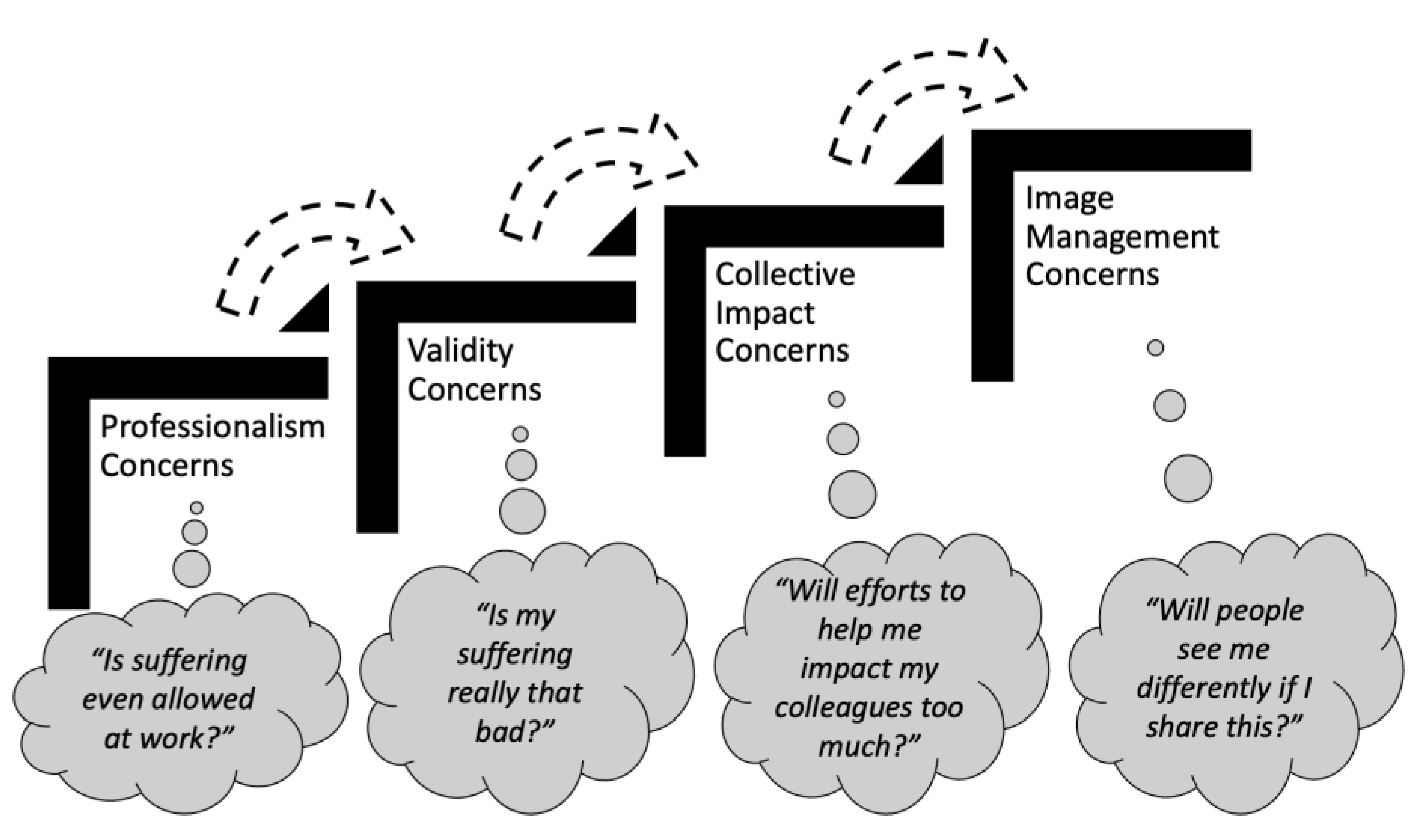

Consequently, this study explores the following research question: What concerns drive employees’ hesitation to disclose and discuss suffering at work? Drawing on qualitative, semi-structured interviews and a positively deviant sample of suffering employees who have experienced compassion from a leader, we found that employees have four driving concerns that limit their expressions of suffering: (1) professionalism and the appropriateness of suffering, (2) the validity of one’s suffering, (3) the collective impact of a compassionate response, and (4) image management. These concerns are layered together in ways that influence employees to withhold suffering altogether or, when they disclose, significantly constrain how much they share with compassion providers. Consequently, these factors constrain compassion and, in some cases, may even exacerbate suffering.

3. Materials and Methods

To understand the subjective experiences of suffering employees, this study utilized qualitative, in-depth, semi structured interviews [

37]. A qualitative approach offers the ability to explore the nuances behind participants’ concerns, including how those concerns emerged across the compassionate interaction [

37]. Where a quantitative approach to answering our research question may have elicited a greater quantity of responses from employees, it would have lacked the rich descriptions captured from the interviewer’s probing questions, likely obscuring how these concerns manifest across the compassionate interaction and within the compassion sub-processes. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and responded to guidelines for research during COVID-19.

3.1. Data Collection and Participants

Our sampling was purposive [

37,

38], focusing on employees who had received compassion from an organizational leader. We targeted this group for two reasons. First, we targeted employees who had experienced compassion because we wanted to understand concerns across the compassion process. Put another way, we needed to be able to understand how these concerns manifest not only in initial disclosure but across the interaction. Secondly, we focused on compassion from organizational leaders because they are often gatekeepers to organizational resources (e.g., time off) that may help employees, making them the individuals most likely to provide compassion across a wide range of employee suffering.

To establish this purposive sample, we utilized case selection procedures in line with positive deviance case selection [

39]. Positive deviance refers to non-normative behaviors within a group that are positive in intent [

40]. As noted, extensive research suggests that employees may hesitate to disclose suffering at work [

31,

32,

33] and that compassion often fails to unfold within organizational contexts [

9,

16]. Consequently, because we cannot assume compassion regularly unfolds within organizational contexts, we see compassion from an organizational leader as positively deviant.

We drew on guidelines from Bisel and colleagues [

39] in order to establish positive case boundaries; these were participants who met the following criteria: (1) employees who were able to identify an organizational leader, (2) consider this leader to be compassionate, and (3) have personally experienced compassion from this person in the last year.

For recruitment, the first author utilized various networks (face-to-face, email, LinkedIn, and Facebook) to distribute the initial call, which asked for people to forward the call as a form of snowball sampling to maximize participants. After 21 participant interviews, the first author engaged in a second round of purposive sampling to increase BIPOC and LGBTQ+ participation. To do so, the author contacted individuals who had offered to help expand the participant pool, asking that they forward the call to qualifying participants if they felt comfortable. These efforts resulted in 10 additional interviews for a total of 31.

Interviews were conducted via Zoom by the first author, where audio and video were recorded in line with IRB guidelines. Before interviews, all participants completed a demographic form and informed consent. Zoom produced automatic transcriptions, which were reviewed for accuracy by the first author. The 31 interviews ranged from 42 to 90 min (M = 69.00, SD = 13.42) for a total of 2154 min. Transcripts totaled 359,959 words, or roughly 800 single-space pages.

We had 31 participants. Participants worked in various industries, including education (n = 13), business services (n = 5), health services (n = 4), finance (n = 3), social services, (n = 2), transportation (n = 1), public administration (n = 1), pastoral ministry (n = 1), and funeral services (n = 1). Fourteen participants identified as male, 16 identified as female, and one identified as genderqueer. Participants identified as heterosexual/straight (n = 22), gay (n = 2), and bisexual (n = 1). Five participants chose not to disclose sexual orientation. Participants identified as white (n = 20; 64.5%), Asian/Asian American (n = 3), multiracial (n = 2), Latino/Hispanic (n = 2), Native American (n = 1), Black/African American (n = 1), African (n = 1), and Middle Eastern (n = 1). Participant ages ranged from 20 to 42 years (M = 31, SD = 4.91). Participants also held different education levels, including bachelor’s degree (n = 12), master’s degree (n = 14), and doctoral degree (n = 5). Median household income was $75,000–100,000, with the highest earning $275,000–300,000 and the lowest earning less than $25,000. Additionally, participants reported being in their current role for an average of 27.20 months, with a low of two months and a high of 82 months (SD = 20.30 months, Mdn = 18.50 months). We use pseudonyms for all participants in this paper.

We also captured demographic data for the compassionate leader participants discussed in interviews. Leader ethnicity included white (n = 24; 77%), Asian/American (n = 3), Black/African American (n = 2), Latino/Hispanic (n = 1), and biracial (n = 1). Eleven leaders were male, while twenty leaders were female. Participants knew these leaders for varied lengths of time, ranging from 6 months to 204 months (M = 36.00 months, SD = 39.00 months, Mdn = 25 months).

3.2. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted in line with a phronetic iterative approach [

37], which balances emergent findings with the researcher’s preexisting interests and knowledge. Sixteen transcripts underwent first-cycle coding, focusing on the question “What is going on here?” [

41]. This yielded several hundred codes, which were then reduced by merging codes that were conceptually similar (i.e., “door always open” and “she made that door so open”), in line with pattern coding [

42]. This merge reduced the number to around 100 codes. Codes were further reduced by eliminating any codes that did not attend to the research question or connect with the prior literature [

43], leading to a codebook of 25 codes attending to the RQ; this included the name of code, abbreviation, code name, description, and in vivo examples from transcripts.

Utilizing this codebook, the first author coded the remaining transcripts while attending to new data. Several new codes emerged, which were added to the codebook. Throughout, the first author took analytic memos [

42] related to the data, and noted vignettes and examples.

4. Results

This paper explored the following question: What concerns drive employees’ hesitation to disclose and discuss suffering at work? Participant stories revealed that hesitation to disclose and openly discuss suffering at work was pervasive, even when participants self-identified as having a compassionate leader who responded to their suffering. We found four core concerns that drove this hesitancy: (1) Professionalism concerns, which shaped views about the appropriateness of sharing suffering, (2) validity concerns related to their suffering, (3) collective impact concerns related to the compassionate response, and (4) image management concerns. Importantly, and as depicted in

Figure 1, these concerns spanned across the compassion processes, acting akin to layers that had to be considered one at a time as suffering employees made sense of their decision to disclose and discuss suffering. In what follows, we outline evidence for these four core concerns, highlighting the sources of these concerns and their impact on the compassion process.

4.1. Driving Concern 1: Professionalism–“Is Suffering Even Allowed at Work?”

The first driving concern that emerged across our interviews related to participants′ perceived feeling rules about what was (and was not) appropriate to disclose at work. Most often, participants referenced varying conceptions of “professionalism” as the foundation for these feeling rules, which they believed restricted personal sharing at work. Research on professionalism within the United States had documented this sentiment, often excluding personal, strong emotional displays at work [

31,

44]. The primary source of professional expectations was broader discourses of professionalism and work. Although our participants did cite leadership dynamics and organizational context as contributing to professionalism, this was often seen as either exacerbating or challenging preexisting notions of professionalism that the employee carried into the workplace.

Many participants described how broader discourses of what it meant to be professional at work conditioned them to believe that disclosing suffering at work was inappropriate and, consequently, a risky endeavor. Dakota, a 41-year-old special education director, talked about professionalism when recalling marital difficulties that complicated both her personal and professional life.

I have always been extremely professional, and I try to put on my mask and go to work and get stuff done. That’s what you’re trying to do right? You go to work, and your job is about kids, and taking care of them and their needs come first.

Dakota invokes imagery of a mask to suggest that employees must cover up their personal issues to fulfill their professional role. In the interview, Dakota discussed this view on professionalism as a matter that is always assumed within organizational contexts. She went on to reflect how ingrained this expectation was within her past work experiences. “[At my previous job], it’s a very nine-to-five situation—you don’t bring your personal life to work. And if [my personal challenges] had been there, it would have been a very different scenario.”

Other participants cited similar assumptions around professionalism that encouraged employees to suppress personal emotions at work. Mackenzie, a 37-year-old marketing director, said that professionalism at work often leads people to pretend they are doing okay despite their actual circumstances.

There’s so much in the work culture where—and I get it, right, you go to work and you are a professional, and you go to work and act professionally—but there’s a lot of like, what does professional mean? And when someone says, “How are you doing today?” should you be honest and say, “No, I’m having a shitty awful day” or do you say, “Oh, you know what, I’m fine Susie, everything’s great, butterflies out the butthole.”

Mackenzie’s candor reveals her own frustrations about how professionalism can create a false paradigm where people suppress their authentic emotions even when others genuinely ask how they are doing. This, in turn, reinforces social norms that make it difficult for people to disclose when they are not doing well. For Mackenzie, professionalism and being a “good coworker” means that you only bring your professional side to work.

Other participants shared that supervisor and leadership dynamics can further reinforce the idea that employees should not share their personal emotions at work. Dakota talked about how prior leaders reinforced discourses of professionalism by creating “imaginary lines that you just don’t cross,” signaling a clear hierarchy.

You just don’t talk about certain topics. They don’t joke about certain things, and they don’t show up to the little staff barbecues or those kinds of things. There’s always this imaginary line. It’s kind of us against them, which is ridiculous, but that’s kind of how it feels.

Regardless of the leaders’ actual views on professionalism, Dakota’s impression from their interactions is that they want professional boundaries that exclude personal disclosure, which reinforces uncertainty about what is and is not appropriate to express at work.

Gage, a 31-year-old director in the technology industry, reflected on similar challenges when sharing personal experiences with leadership. As a middle manager trying to advocate for his struggling employees, he said that he often felt that leadership minimized these concerns even when they were directly expressed. When I asked about his own experiences disclosing personal suffering, he said that he tried to express challenges personally as well, but often felt hesitant due to his experience advocating for employees.

I know that I’ve tried to communicate [suffering] about myself. I’ve definitely communicated about [others as well], like “Hey, I’m hearing this [from other employees in the organization].” [Leadership] doesn’t really respond well to those kinds of things in general, and I get it. The whole “people are saying this” approach to making a point generally doesn’t go over well for executive leadership because it sounds like a hollow point. But I also think that people in general are afraid to vocalize how they actually feel to leaders.

Gage’s frustration helps capture a double bind that often manifests in organizational contexts. On the one hand, expressing suffering for others is generalized and anonymous, and thus may not be well received by leadership. On the other hand, individuals often do not feel comfortable disclosing their personal struggles directly, especially with leadership. These dynamics then become self-reinforcing. Leaders do not create change, which makes employees feel that they do not care. When employees feel that their leaders do not care, they express even less, which unfortunately ends up reinforcing leaders’ views that there are not major issues.

Organizational context can also exacerbate the feeling that there are rules that limit personal sharing at work. Alexis, a 32-year-old medical resident, described how medical schools often reinforce values of excellence and accuracy. While important values, they often implicitly create a culture in which it is difficult to acknowledge failure or shortcomings. Alexis reflected on this dynamic when recalling her personal struggles in dealing with the loss of a patient at work.

The personality of medical schools is you want to do things right all the time, and you want to get praised for that too. And whether or not that’s a good thing, that’s the environment that you’re in during medical school and it continues into residency. And so I don’t know if it was the right part of me that needed to hear it, but it did help to hear [from my leader] that I did everything right.

Due to the organizational culture, Alexis shared that it was incredibly impactful for her leader to emphasize that she made all the right medical decisions when working with this specific patient. What is interesting, however, is that Alexis later acknowledged that she knew deep down that she had not made any incorrect medical decisions that caused the patient harm. Rather, the organizational context led her to feel that she could not process her feelings openly, which constrained her ability to work through some of her initial emotions. In this case, simply giving her permission to process her emotions and normalizing her reaction was an act of compassion from her leader.

Samantha discussed a similar dynamic when she reflected on how unique it was to be able to relate personally to her leader. As a 32-year-old working in finance, the organizational context came with high levels of professionalism that limited personal sharing.

I mean it was a very buttoned-down place. And so I could kind of sense it, you know? Not as much with [my leader], but I kind of knew that it was a privilege to be able to relate to her in the way that I was, and I knew there is a level at which it’s not appropriate to get into.

As Samantha notes, the context reinforced boundaries around emotional expression to the point that she felt it a privilege to have a candid relationship with her leader. This, however, was seen as unique within the industry and organizational context.

In summary, the first driving concern for employees was related to a feeling that it was inappropriate to disclose personal suffering at work. The feeling that there were these restrictive rules largely came from broader discourses around professionalism, which were further exacerbated by specific organizational contexts and leadership dynamics. When present, the impact of this concern was that employees often withheld personal suffering or, when they shared, minimized the depth of their sharing.

4.2. Driving Concern 2: Validity of One’s Suffering–“Is My Suffering Really That Bad?”

The second driving concern that emerged from our participants was uncertainty that their suffering would be seen as valid by others, often articulated colloquially as, “Is my suffering really that bad, especially compared to other types of suffering?” Research on compassion has identified that the validity of suffering is a driving factor as to whether or not a compassion provider may respond empathetically to suffering [

12]. In the present case, participants proactively anticipated whether they believed others would view their suffering as valid, and when they worried about that appraisal, tended to withhold their suffering. Suffering type and severity tended to guide sufferers’ proactive assessment of others’ appraisals. Additionally, a few participants suggested that certain types of suffering were ambiguous and difficult to describe (e.g., mental health challenges), which also created concern that others would see their suffering as valid.

Amir, a 26-year-old medical research coordinator, captured the idea that some types of suffering may not be seen as valid compared to others when reflecting on loss in his own life. Amir lost both his grandmother and his dog within a few months after starting a new job. Both losses deeply impacted Amir. However, he said that he felt losing a dog would not be seen as severe or valid in the same way losing his grandma would be. Therefore, while he did disclose that he lost his pet, he initially minimized how deeply this was impacting him and did not ask for any time off. Fortunately, Amir’s leader proactively validated his suffering by acknowledging that pet loss can be significant for many people and created space for him to more openly process his suffering.

I’d say I began to get more comfortable with her when my dog passed away. I [had been] in the position for about four and a half months at that time, and you know, I’d say normally the way I would even respond to [someone’s dog passing] would be like, “Oh sorry, you know, you lost a pet. I’m sure they were near and dear to you,” and, “You know, if there’s anything I can do let me know.” You know, the pretty standard stuff. But then for her to go, “Losing a pet is not easy. How’s your mom doing? I know that when you lose a pet, you just remember loss that you have in your life. This probably reminds you of your grandma. How is all that?”

As Amir notes, even he would potentially minimize pet loss comparative to other types of loss, implying a sort of hierarchy of suffering. Much of this makes sense. Not every kind of suffering impacts people at the same level. However, the risk with this kind of logic is that it may create a situation, as it did for Amir, where someone is more deeply impacted by a particular kind of suffering and may not feel comfortable expressing that. Amir was fortunate that his leader proactively created space for him to share. Without it, Amir likely would have minimized his loss and not taken the proper time to grieve.

Gage reflected a similar sentiment that only larger, more broadly acceptable types of suffering are typically honored at work, creating uncertainty for employees to share other kinds of suffering. In Gage’s view, only severe, acute, and broadly known types of suffering (e.g., losing a loved one, receiving a severe medical diagnosis, etc.) were honored with tangible resources at work, such as time off or other kinds of assistance. Consequently, other types of suffering that may be harder to see or articulate (e.g., mental health concerns) seemed to be seen as less valid because they were rarely rewarded with the same level of compassion.

I think there’s this feeling where it seems like a lot of people get these really cool experiences [in response to suffering] that I don’t get. And not the tragedy piece, obviously, I don’t want that. But where is that level of care for me or for other people who I know are suffering but maybe there’s a higher explanation of what work and stability and what version of themselves is this person going to bring to the table…

Gage felt that his organization only responded to larger, more widely accepted forms of suffering and, therefore, implicitly devalued or invalidated other types of suffering. Gage believed that these other types of suffering were equally valid but often more nuanced in the ways that they impacted work. In Gage’s case, his mental health struggles with anxiety and depression significantly impacted his work and were personally draining, but he struggled to articulate them in a way that he felt leadership would understand and validate.

Gage’s story not only captures how the perceived validity of suffering may guide employees’ choice to disclose suffering, but also the ambiguity of articulating their suffering. As he noted above, many types of suffering require a “higher explanation” because they do not fall within the widely accepted forms of suffering that are recognized. When someone says that they have lost a loved one, people can widely trust that others will see this as a significant loss. However, mental health challenges such as depression, though gaining recognition, manifest and impact people in a wide variety of ways. Consequently, one may struggle to clearly articulate the acute impact of their mental health concerns in a way that others readily understand. Our findings suggest that in these cases, the ambiguity of articulating suffering may lead sufferers to believe that others will not see their suffering as valid and therefore not disclose their struggles.

Across Gage’s interview, he expressed a level of discomfort even when discussing any sort of rank-order for suffering. This discomfort extended to his own feelings and the sense that he deserved more of a compassionate response, recognizing the ways this might take away from the suffering others were experiencing. Still, Gage could not get past the feeling that his own (and others) suffering did not “count” in the same way as others, going unrecognized and therefore not met with the same compassionate response.

In summary, the second driving concern that constrained employees’ ability to disclose and discuss suffering was a concern that others would not see their suffering as valid. This assessment was influenced by the type and severity of their suffering, as well as the ambiguity they felt describing their suffering. When employees fear that their suffering will be perceived as invalid, they tend to not disclose their suffering or minimize the needs they have around that suffering. In both cases, their ability to receive compassion is constrained.

4.3. Driving Concern 3: Collective Impact–“Will Efforts to Alleviate My Suffering Impact My Colleagues Too Much?”

A third driving concern was related to how participants believed a compassionate response may impact their colleagues at work. When it seemed that a compassionate response would impact their colleagues (e.g., add additional work for them), they tended to prioritize this potential collective impact over their own individual needs. While this concern was not universal, when present, it constrained what employees asked for and even accepted in terms of compassionate action. For some participants, this manifested when they had chronic, longstanding forms of suffering that did not resolve quickly. In these situations, sufferers often worried about the continual impact on their colleagues and leaders when they were unable to fully accomplish their work duties.

Mackenzie found herself in this type of situation as she navigated a second round of brain surgeries. Her organization said clearly that she could take “all the time [she] needed,” an especially compassionate response that differed greatly from previous organizational experiences. However, even though she perceived this offer as authentic, she still found herself trying to interpret what “all the time you need” meant in practice. Mackenzie started to feel the weight of this uncertainty after her initial surgery and recovery.

I think when I first got done with surgery, there was still worry that even though they said “Hey, take all the time you need,” there’s still that question of, “Am I taking too much time?” Or, you know, feeling like I’ve been gone for so long. There was still that anxiousness to get back to work.

Despite her organization’s explicit invitation to take whatever time she needed to take care of herself, Mackenzie still felt pressure to get back to work and minimize the potential impact for others, even acknowledging that she checked her email from the hospital. Mackenzie noted that prior experiences at work had led her to believe that taking too much time off would be viewed negatively by coworkers, as your work will often fall to them. Therefore, even when her organization told her to take time for herself, she was still hesitant about how liberally she could interpret this message, especially as she navigated ongoing health issues that could be unpredictable.

In other situations, employees actively resisted offers of help, even in acute situations. Nancy, for example, expressed a view that one’s personal suffering should never impact one’s work. Therefore, when Nancy, a 21-year-old technology manager, experienced a significant disruption in her life, she initially resisted help. Nancy found herself in a trying situation when she was informed that someone who may have sought to harm her and others in her family had escaped from prison. In response to this shocking revelation, her organizational leader offered policy changes and the use of company funds for rides to and from work to secure her safety. However, Nancy’s initial reaction was that these were inappropriate, recalling that it “was crazy. It’s not the company’s problem. It’s not the company’s fault for me to expense [car rides]. It was, for the company to do that, incredibly generous and even unnecessary.” Nancy’s concerns were not about the appropriateness or validity of her suffering, but on its potential impact on her leader, her colleagues, and the organization itself. This belief was so engrained for Nancy that, while she did eventually accept some assistance, she actively resisted it for several days despite the severe circumstances.

In summary, the third driving concern for employees centered on the ways that a compassionate response to their suffering may impact their leader or colleagues. These concerns were especially salient when employees’ suffering spanned over a longer period of time, such as with chronic health conditions. When this concern was present, employees tended to not ask for what they needed and, in some cases, actively resisted offers of help.

4.4. Driving Concern 4: Image Management–“Will People View Me Differently If I Share My Suffering?”

A final driving concern was centered around image management and how expressing suffering might shift the way that others perceive the sufferer. Undoubtedly, many of these perceptions intersect with (and stem from) ideas around professionalism, validity, and collective impact. However, they also reflect the personal image management concerns that employees have at work, often arising from a desire to be seen as competent by others. Perhaps most interestingly, image management concerns not only drove the way that employees disclosed and discussed suffering, but often created lingering concerns even after they received a compassionate response. Put another way, employees still worried about their image at work even when their suffering was met with compassion.

For many participants, image management concerns stemmed from their own personal desire to be viewed positively by others. Parker, a 31-year-old healthcare worker, shared how his own insecurities around his image often caused him to suppress emotions at work.

So for me and [knowing my personality type], I care a lot about what other people think about me and I’m very goal driven…so when I’m in a less healthy developed state I don’t want to share these things because I’m worried about what they’re going to think about me and think that I don’t have it all together.

Parker, like other participants, had real fears about how sharing his personal suffering may shift others’ perceptions of him. Consequently, he often chose to withhold suffering. Over time, however, Parker realized that he needed to lean into vulnerability in order to push through these concerns. “I think it’s being okay with tapping into vulnerability and caring less about what that other person is going to think…” To receive compassion at work, Parker needed to not only navigate professional expectations, but also his own insecurities and needs around self-image.

Kelly, a 32-year-old higher education professional, echoed a similar sentiment when she reflected on the unrealistic image she had constructed of herself in the workplace. As she described, the image she created of herself to show her leader was of a person who could “do all things,” which did not allow space for challenging life events that disrupted work. Later, when Kelly and her partner went through an extremely challenging period while pursuing foster parenting, she was suddenly unable to maintain this image. When asked if there were particular topics she did not feel comfortable disclosing to her leader, she discussed this dynamic.

I would say there were [topics we couldn’t discuss before] and there aren’t now. Two years ago, especially with the [child foster care] process and the weirdness of that, I just couldn’t [do everything in my job I had committed to]. Part of it was my own pride. But, I wasn’t ready to admit to [my leader] that I couldn’t do all the things I said I was going to do…I wouldn’t say I felt like he would shame me or that it was inappropriate to ask…but he wasn’t really inviting that type of feedback.

As Kelly reflects, personal pride limited her willingness to share personal struggles with her leader, especially given that this would contrast with the image she had cultivated at work. Consequently, because her leader did not explicitly invite her to share personal challenges, it became easier to withhold her own suffering. In Kelly’s case, her leader eventually learned to ask more specific questions, which helped to draw out how she was doing and made her feel comfortable sharing her personal challenges. However, one can see how many others might construct images early in their job that suggest that they never have challenges, only to later be constrained by the expectations implicit in that image.

In other cases, participants voiced the concern that expressing suffering would cause others to question their competency at work. Camille, a 39-year-old public administrator, reflected on this when she described how she broke down in tears in front of her leader.

So it leaves me wondering sometimes if she worries about my competency, especially when I … [broke down into tears]. I did wonder, “Does she think I’m weak?” or “Did I show too much?” Or “Do I have to make up for this?” And there are still times when I hesitate to show everything because I’m still worried about a perception of not being strong enough or not being competent.

As Camille shared further, she did feel cared for by her leader in that moment, one of many examples of her compassionate care. However, even with this caring response, she was still unsure later as to whether this shifted her leader’s view of her. Now, despite never explicitly affirming her image management concerns, Camille still hesitates to share suffering at work for fear that it may undermine her image as a competent employee.

Elinor’s experience further illustrates the cascade of image management concerns that may quickly overwhelm suffering employees. Elinor, a 37-year-old teacher and administrator, endured a painful breakup that greatly disrupted her life and made it difficult to carry out her day-to-day tasks at work. Even in the face of such acute suffering, she did not disclose the breakup to her leader for several weeks. When asked how she made sense of her decision to wait, she said she was not sure how it would impact her image at work.

…I guess I just didn’t know how it would be perceived. “Am I trying to get out of work?” or “Am I not tough enough to work through this?” I guess what I’m really saying is it’s all me, those were all my perceptions. Because again, [my leader’s] response was so incredibly understanding. But I was thinking about the scenario of “How would this change your perception of me?” Of course, she’s going to be understanding. But would she also think she can’t rely on me in another situation? Or would this undermine my credibility as someone that can balance multiple things and balance them well.

You can see how Elinor herself struggles to fully articulate how this would be perceived, highlighting the implicit ways employees wrestle with image management concerns. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this is that these concerns emerged even though she had confidence that her leader would respond compassionately. In other words, even though these “were all [Elinor’s] perceptions,” she still found herself ruminating about the potential negative impact on her image at work.

Francesca, a 25-year-old business operations specialist, felt similar image management concerns, especially because she felt that mental health concerns were often stigmatized at work.

I didn’t want to tell her [specifically about mental health challenges] because I was nervous she would think of me differently. And now looking back, I know she wouldn’t have. But because we were at a work setting I decided to not let that out beyond HR. I don’t know…some people have different stigmas toward it and it’s just “You’re at work, do your work.” …So I think that was more just a work decision and that I wasn’t sure how she would react because I’m not sure how anyone would react.

Similar to Elinor and Camille, Francesca was still processing her decision not to disclose her worries, given how compassionate she had found her leader to be. In this case, however, she felt that mental health was stigmatized in a way that meant she could not trust how it might shift others’ view of her. Therefore, even though she knew her boss “wouldn’t have seen her differently,” she deemed it too risky to disclose her worries and simply told her leader that she needed some time off to deal with personal issues, limiting her leader’s ability to offer care and support.

In summary, the final core concern of employees in relation to disclosing and discussing their suffering is that doing so will damage their image at work and cause others to interact with them differently. These image management concerns stemmed from individuals’ desire for a positive image, concerns that suffering would be perceived as a lack of competence, and the stigma associated with particular kinds of suffering. When this concern is present, employees tend to withhold their suffering or, more often, disclose only minor details of their suffering, which limit the compassion they can receive.

5. Discussion

This study explored the stories of suffering employees who received compassion from an organizational leader, and in doing so, revealed four driving concerns that limit the open sharing and discussion of suffering in the workplace: (1) professionalism and its implications for the appropriateness of sharing personal suffering, (2) the validity and severity of one’s suffering, (3) the collective impact of a compassionate response on others, and (4) image management. Participants’ experiences highlight the precarity of suffering across various organizational contexts and the layered concerns they face when expressing suffering, even when they regard their leader as being highly compassionate. In what follows, we unpack these driving concerns, connecting them to the relevant literature and explaining how this analysis extends the understanding of compassion at work.

Professionalism and its impact on emotional expression formed the foundation of our participants’ concerns. While early discourses around professionalism positioned emotions as being inappropriate at work [

33] due to their hindrance to rational decision making [

31], more recent scholarship has embraced emotions as being more legitimate [

45]; for example, they help solve problems [

46] and address unethical behavior [

47]. Despite this shift in scholarship, our participants consistently echoed early conceptions of professionalism as emotionally restrictive, which heavily shaped how they made sense of expressing suffering at work. Many referenced the need to put on a mask at work, alluding to the dichotomy of a “fake” organizational self that stands in contrast to their “real” personal self [

34].

While professionalism was most explicitly cited regarding concerns about the appropriateness of disclosing suffering at work, internalized ideas stemming from this view on professionalism undoubtedly shaped employees’ other driving concerns. Image management, for example, was largely driven by an understanding that expressing personal suffering at work may lead others to see them as weak or incompetent in their role. Meanwhile, emotion and personal suffering are positioned as being a form of weakness by discourses external to work, such as masculine expectations not to express emotions [

48]; this is because, within organizational contexts, employees link intense emotional displays with competency. Similarly, participants held a similar view that undergirded their concerns about the collective impact of a compassionate response, where they felt that their personal challenges should not interfere with work. This perspective led many to prioritize potential collective impact over their individual needs, sometimes going so far as to turn down compassionate actions if they felt that they might impact others too much.

Participants’ concerns regarding validity echo ideas of professionalism, but also illuminate the ways that the suffering type and severity influence how employees make sense of their decision to disclose suffering. Many participants worried that their suffering would not be seen as “bad enough” to warrant empathy and compassion. Indeed, compassion scholarship suggests that these evaluations of suffering by compassion providers may influence whether or not the compassion provider feels a sense of empathy and responds compassionately [

12]. We found that these appraisals not only influence compassion providers but sufferers as well, as they proactively anticipate how others will appraise their suffering, which informs their decision to disclose. Suffering type and severity heavily influenced employees’ proactive assessments, where most felt that only severe, acute, and widely understood forms of suffering could be trusted as universally valid (i.e., loss of a loved one or a significant health diagnosis). Other forms of suffering left them uncertain as to how it would be perceived. Pet loss, for example, was seen by one participant as “lesser” than human loss, and therefore likely to be seen as invalid. Others felt that mental health concerns were often too ambiguous or not acute enough to be viewed as valid. Therefore, when employees experience a form of suffering that they feel is not acute, widely understood, or easy to articulate, they often withhold their suffering or, if shared, downplay its significance.

In practice, many suffering employees had to work through these concerns like layers being peeled back to get to the core, which is compassion for their suffering. When taken collectively, the subjective experience of our participants suggests that suffering itself is largely disenfranchised within organizational contexts because it is invalidated by relational, organizational, and discursive influences. Here, there are clear parallels to disenfranchised grief [

49], a concept referring to those who feel that they cannot openly acknowledge and process their grief for fear that others will see it as invalid. Disenfranchised grief has been shown to limit people’s ability to perform the emotional, psychological, and spiritual work they need to do to process grief, especially in organizational contexts [

7]. By contrast, we found that a broad range of suffering type and severity was disenfranchised within organizations, not only the losses typically associated with grief (i.e., loss of a loved one). Consequently, these layered concerns shape employee sensemaking in ways that mean they often decide that suffering is not safe to express at work.

The disenfranchisement of employee suffering through their layered concerns about suffering at work has direct implications for their engagement in the compassion process. The first and most immediate implication is that these concerns restrict, or at least significantly limit, their engagement in the compassion process, in line with recent theorizing related to how uncertainty may limit compassion at work [

16]. When employees choose not to disclose their suffering, compassion is absent. In addition, while compassion theory suggests that compassion providers may recognize another’s suffering, such as the case of emotional leakage [

50], we found that this rarely happened in practice. Rather, suffering employees almost always volunteered their suffering. In turn, if one’s ability to disclose suffering is restricted, compassion is unlikely to unfold.

Even when employees did disclose their suffering, they often limited the depth they shared with compassion providers. For example, some participants described how they would downplay the significance of their suffering, which often led compassion providers to not respond with the appropriate urgency or scale of response. In other cases, participants limited the details they shared, such as one participant who was dealing with severe mental health concerns but told her leader that she was just having a long week. Here, the leader lacked enough detail to know how to even begin to help her employee. Employees also felt unsure of what they could ask for to alleviate their suffering, and, in other cases, even proactively downplayed their needs for fear of how a compassionate response to alleviate their suffering would negatively impact the collective group. Therefore, even when leaders knew details of their suffering and how they might be able to help, many sufferers limited compassion by restricting how they asked for and received compassion from leaders.

Our findings suggest that these driving concerns may also exacerbate employee suffering beyond simply constraining their ability to receive compassion. Participants described agonizing over their decisions to share suffering and, even when they did disclose, they often continued to dwell on the potential negative implications they could face. Suffering itself is an extremely vulnerable state for those that experience it [

51], and the layered concerns present within organizational contexts often exacerbate this vulnerability [

7,

16]. Even further, suffering is often ambiguous [

52], where many types of suffering, such as grief and loss, have a nonlinear and unpredictable path [

53]. Consequently, the need to navigate uncertainty and image management concerns to receive compassion at work adds undue burden to an already overwhelmed sufferer. This may lead to what Driver [

54] describes as preventable suffering. Drawing on Frankl’s [

55] framework, Driver [

54] draws a distinction between inevitable and preventable suffering. Inevitable suffering cannot be avoided, such as the loss of a loved one or personal health issues. Preventable suffering, however, is suffering that is caused by others that need not have occurred. In the present case, navigating multiple layers of concerns to receive compassion when one is already in a vulnerable state is likely to further exacerbate one’s suffering. This disenfranchisement of suffering, then, not only restricts individuals’ ability to receive compassion, but may exacerbate their suffering as well.

To summarize, our exploration of suffering employees’ subjective experiences highlights the precarity and challenges associated with personal suffering in organizational contexts. Employees face a variety of driving concerns that layer upon each other, compounding the difficulty of expressing and openly discussing their suffering. Given that compassion is driven by individual sensemaking, many suffering employees may simply decide that expressing suffering is too risky, limiting their ability to receive compassion at work. Given the pervasiveness of these concerns within our study, it is likely that these driving concerns help explain why compassion so often fails to unfold within organizational contexts. Our confidence in this is further bolstered by our positively deviant sample; given that we found uncertainty where we would least expect to find it (i.e., with compassionate leaders), it is even more likely that these findings can be generalized to other cases [

56].

6. Practical Implications, Limitations and Future Directions

Our study has practical implications for those hoping to cultivate greater compassion at work. First, leaders who want to cultivate compassion at work may do so by creating more openness to disclose and discuss personal suffering. The specificity of the concerns that our employees outlined suggests a roadmap for the messaging that leaders could adopt. For example, leaders could craft messages that signal that personal suffering is appropriate to share at work, which would create positive sensemaking resources for employees to counterbalance their concerns [

57]. In addition, leaders could regularly talk about the need for coworkers to support each other with their work-related tasks when personal challenges arise, which may help alleviate concerns around collective impact. The key is that leaders can use language to create alternative narratives within their organization that may counteract employees′ driving concerns when they consider disclosing suffering, therefore minimizing how much they constrain compassion.

Secondly, organizational leaders may consider policies and structures that allow suffering employees to receive compassion without having to directly navigate their disclosure concerns. For example, an anonymous ombudsperson may provide space for suffering employees to seek support without having to navigate disclosure concerns or worry that their suffering would be widely known. Additionally, organizational leaders might craft bereavement or leave policies that apply to a wide range of needs. For example, rather than having a bereavement policy that can only be used when someone loses a loved one, as many organizations have, one could have a personal leave policy that could be used for a range of challenges without having to disclose or justify their use of it to leadership. These options would allow employees to pursue the resources or time they need to deal with their suffering without having to engage with leaders or colleagues directly, therefore potentially bypassing some of their concerns.

This study, like all studies, also has limitations. First, while the concerns of our participants were relatively universal and spanned various demographic identities, we still need to know more about the additional concerns of those holding traditionally marginalized identities, and the contexts in which these concerns become salient. For example, does suffering that is tied directly to one’s identity (i.e., a trans employee facing microaggressions after transitioning at work) create new concerns or challenges when expressing suffering and receiving compassion? Our study, while relatively demographically diverse, is not meant to suggest that all employees face these same concerns or that there are not additional concerns that may further complicate one’s suffering. In addition to demographics, our study also focused primarily on white collar organizational contexts. It may be that blue collar or other work contexts have different or additional challenges surrounding compassion.

These limitations suggest two fruitful areas of future research. First, we need to know more about the experiences of those holding traditionally marginalized identities, as well as the experiences of those working in blue collar and other organizational contexts. Further exploring these contexts will strengthen our understanding of more generalized challenges associated with compassion, as well as illuminate the context-specific challenges that individuals face. Secondly, future research could explore the boundary conditions around personal sharing at work. This paper could, unwittingly, suggest that organizations committed to compassion should create cultures in which unbridled personal expressions of suffering abound. While this may, in theory, support greater compassion, it may also create a variety of complications and challenges as well. Future research could work to understand the unintended consequences that are associated with a more open disclosure of suffering at work, both for organizations and for individuals, as well as how we might theorize the balance and boundary conditions of personal and professional goals.