The Internal and External Factors of Environmental Destructive Behavior in the Supply Chain: New Evidence from the Perspective of Brand-Name Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. The Concept of Environmentally Destructive Behavior in the Supply Chain of Brand-Name Products

2.2. Internal Environmental Management in the Supply Chain

2.3. Enterprises’ Interests in the Supply Chain

2.4. Characteristics of Polluting Enterprises in the Supply Chain

2.5. Environmental Legislation

2.6. Environmental Regulation

2.7. Public Supervision

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measurements

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

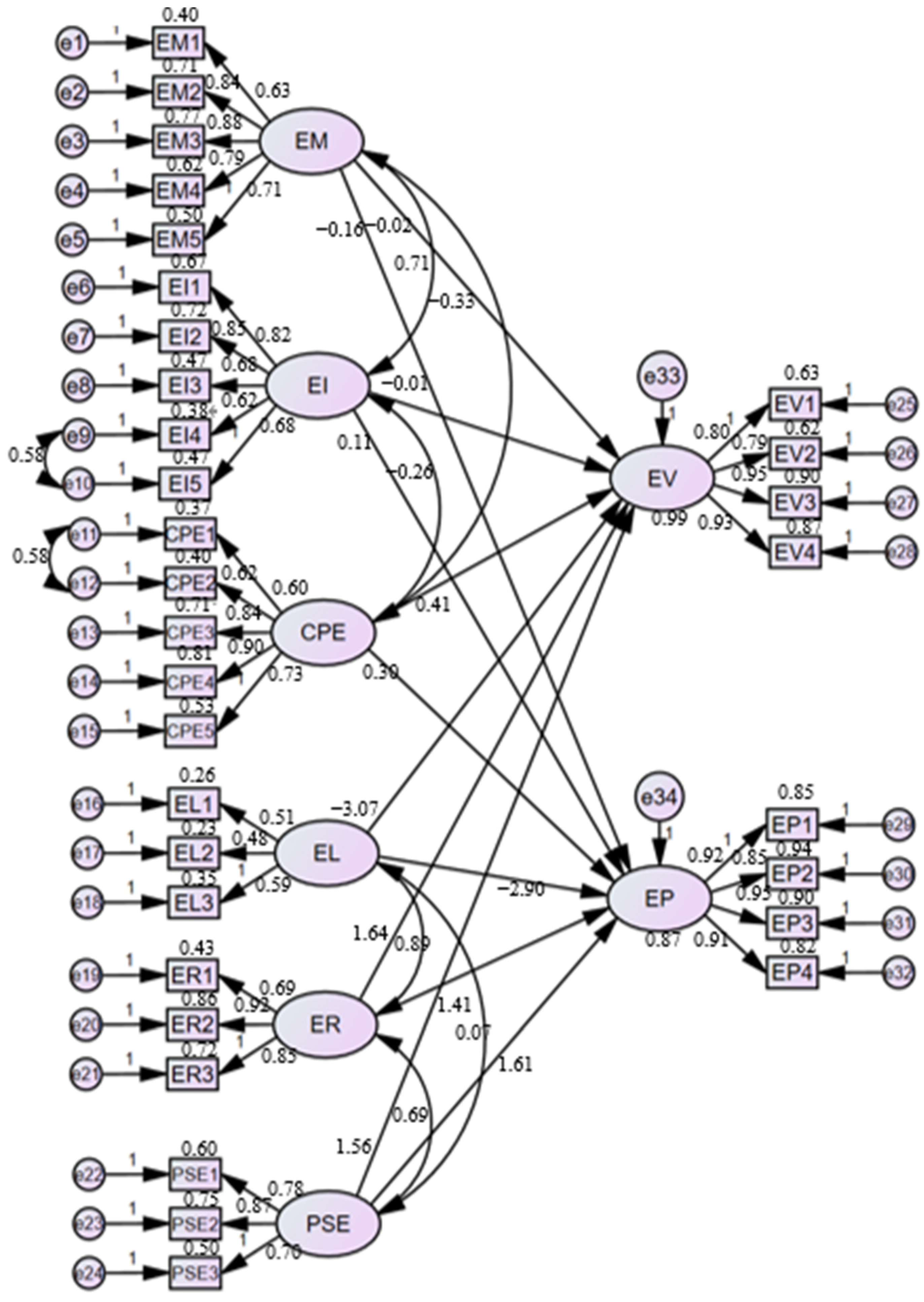

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Structural Equation Model Fitting Analysis

4.4. Interaction Effects of Internal and External Factors Analysis

4.5. Difference Test of Characteristic Variables

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Discussion

5.3. Implications

5.4. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Measure of the Research Scales |

| Environmental Violations (EV) |

| 1. The enterprise in the supply chain had illegally discharge of waste. |

| 2. The enterprise in the supply chain had environmental pollution incidents, and the prevention and control facilities had not been rectified as scheduled. |

| 3. The enterprise in the supply chain took pollution control tasks but not completed as scheduled. |

| 4. Brand-name product enterprise hasn’t control over environmental pollution in the supply chain. |

| Environmental Penalties (EP) |

| 1. The enterprise in the supply chain was condemned by publics for environmental pollution. |

| 2. Brand-name product enterprise was under the public pressure because of environmental pollution by enterprises in the supply chain. |

| 3. The enterprise in the supply chain was effectively complained by the publics. |

| 4. The enterprise in the supply chain was punished for environmental violations. |

| Environmental Management (EM) |

| 1.Brand-name product enterprise requires enterprises in the supply chain to attain ISO14001 certification. |

| 2. Brand-name product enterprise requires enterprises in the supply chain strictly observe the environmental protection law. |

| 3. Brand-name product enterprise requires enterprises in the supply chain for clean production |

| 4. Brand-name product enterprise requires enterprises in the supply chain to meet pollutants emission standards. |

| 5. Brand-name product enterprise monitors the environmental behavior of enterprises in the supply chain. |

| Enterprises’ Interests (EI) |

| 1. Brand-name product enterprise would reduce orders or terminate cooperation with those enterprises who had environmentally destructive behavior records. |

| 2. Brand-name product enterprise would increase orders or enhance cooperation with enterprises in the supply chain who actively adopt green environmental behavior. |

| 3. Brand-name product enterprise would offer green subsidies to enterprises in the supply chain who actively adopt green environmental behaviors. |

| 4. Enterprises who adopt green environmental behaviors in the supply chain are more likely to gain more market share. |

| 5. Enterprises who adopt green environmental behaviors in the supply chain are more likely to gain the focus and favor of consumers. |

| Characteristics of Polluting Enterprise (CPE) |

| 1. Managers of the enterprise in the supply chain are indifferent to environmental laws and regulations. |

| 2. Managers of the enterprise in the supply chain don’t care about the clean production technologies. |

| 3. Environmental protection equipment are relatively simple in the enterprise of the supply chain. |

| 4. The enterprise in the supply chain are not active in the development of environmental protection technology. |

| 5. The enterprise in the supply chain haven’t set up environmental funds. |

| Environmental Legislation (EL) |

| 1. The government has set pollution standards for enterprises in the supply chain. |

| 2. The government regularly levies sewage charges, border taxes and deposits on the enterprises in the supply chain. |

| 3. The government has taken penalties for environmental pollution by enterprises in the supply chain. |

| Environmental Regulation (ER) |

| 1. The government explicitly requires enterprises in the supply chain to be responsible for the surrounding environment. |

| 2. The government regularly monitors the environmental behavior of enterprises in the supply chain. |

| 3. The government provides subsidies, tax incentives and technical guidance to enterprises in the supply chain who actively adopt green environmental behavior. |

| Public Supervision of Environment (PSE) |

| 1. Public’s pressure on environmental pollution of enterprises in the supply chain is weak. |

| 2.The news media has a low exposure to environmental pollution of enterprises in the supply chain. |

| 3. Environmental NGOs rarely complain or sue enterprises in the supply chain for environmental pollution. |

References

- Du, J.; Wang, W. Research on Environmental Cost Allocation Mechanism of Brand-name Product Supply Chain from the Perspective of Revenue Sharing Contract. Enterp. Econ. 2017, 12, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kucuk, S.U. Macro-level antecedents of consumer brand hate. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Analysis of Formation Mechanism and Influencing Factors of Brand-name Products. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2000, 21, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, M.U.; Aslam, S.; Murtaza, S.A.; Attila, S.; Molnár, E. Green Marketing Approaches and Their Impact on Green Purchase Intentions: Mediating Role of Green Brand Image and Consumer Beliefs towards the Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koplin, J.; Seuring, S.; Mesterharm, M. Incorporating sustainability into supply management in the automotive industry—The case of the Volkswagen AG. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.; Moeller, S. Chain liability in multitier supply chains? Responsibility attributions for unsustainable supplier behavior. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Gil, J.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Garcés-Ayerbe, C. How Is Environmental Proactivity Accomplished? Drivers and Barriers in Firms’ Pro-Environmental Change Process. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, A.; Guan, S. Simulating Environmental Innovation Behavior of Private Enterprise with Innovation Subsidies. Complexity 2019, 2019, 4629457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Chen, Z. Foreign investment, Supply Chain Pressure and Corporate Social Responsibility in China. Manag. World 2015, 2, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Yang, Q.; Qin, L. Research on the Operation Mode and Risk Management of P2P Supply Chain Finance. Contemp. Econ. 2017, 3, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Du, J. Research on Emission Reduction Behavior of Suppliers Considering Famous-brand Product Enterprise’s Environmental Management. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2018, 38, 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, A.; Aslam, H.; Rashid, K. Antecedents of pro-environmental behavior of supply chain managers: An empirical study. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.; Jean, R.; Kim, D.; Samiee, S. Managing disruptive external forces in international marketing. Int. Mark. Rev. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z. A Game Analysis on Cluster Supply Chain Crosswise Cooperation and Environmental Regulation. Econ. Surv. 2012, 4, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, C.; Shi, D. The Emission Reduction Effect of Daily Penalty Policy on Firms. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 112922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, F. Decision Research for Dual-channel Closed-loop Supply Chain Under the Consumer’s Preferences and Government Subsidies. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2016, 36, 3111–3120. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X.; Cheng, H.; Cai, J.; Lu, C. Government Subside Policies and Effect Analysis in Green Supply Chain. Chin. J. Manag. 2018, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Yu, Y. Determination of Optimal Government Subsidy Policy in Green Product Market. Chin. J. Manag. 2018, 15, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Pei, X.; Tang, R. Research on Green Food Supply Chain Agents Coordination Mode Based on Food Green and Reputation. Soft Sci. 2018, 32, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Q.; Du, W. Social Capital, Environmental Knowledge, and Pro-Environmental Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potocan, V.; Nedelko, Z.; Peleckienė, V.; Peleckis, K. Values, Environmental Concern and Economic Concern as Predictors of Enterprise Environmental Responsiveness. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halt, D. Managing the interface between suppliers and organizations for environmental responsibility: An etploration of current practices in the UK. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, S. Supply chain environmental management: Elements for success. Corp. Environ. Strategy 1999, 6, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Dangelico, R.M.; Pontrandolfo, P. Do inter-organizational collaborations enhance a firm’s environmental performance? A study of the largest U.S. companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 83, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Shih, L. Effective Environmental Management Through Environmental Knowledge Management. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 6, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Green project partnership in the supply chain: The case of the package printing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Mallik, S.; Chhajed, D. Design of Extended Warranties in Supply Chains under Additive Demand. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2012, 21, 730–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, S.; He, L. The Optimal Cooperation and Coordination Mechanisms of “Main Manufacturer-supplier” Collaborative Bodies Through Double Efforts. Syst. Eng. 2012, 7, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Creating Shared Value. In Managing Sustainable Business; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2019; pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Subramanian, N.; Rahman, S. Green Supply Chain Collaboration and Incentives: Current Trends and Future Directions. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 74, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Zhang, J.; Tang, W. Cartelization or Cost-sharing? Comparison of cooperation modes in a green supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, J.; Abid, N.; Sarwar, H.; Veneziani, M. Environmental ethics, green innovation, and sustainable performance: Exploring the role of environmental leadership and environmental strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Gusmerottia, N.; Corsini, F.; Passetti, E.; Iraido, F. Factors Affecting Environmental Management by Small and Micro firms: The Importance of Entrepreneurs’ Attitudes and Environmental Investment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Tong, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y. How top management’s environmental awareness affect corporate green competitive advantage: Evidence from China. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 1250–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, F.; Cousins, P.D.; Lamming, R.; Faruk, A. The Role of Supply Management Capabilities in Green Supply. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2010, 10, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, F. Top Management Support, Environmental Innovation Practice and Firm Performance—The Moderating Effect of Resource Commitment. Manag. Rev. 2013, 25, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Zhang, R.; Li, G. Environmental decentralization, digital finance and green technology innovation. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2022, 61, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Long, Y.; Li, C. Research on the impact mechanism of heterogeneous environmental regulation on enterprise green technology innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cheng, Z.; Keung, C.; Reisner, A. Impact of Manager Characteristics on Corporate Environmental Behavior at Heavy-polluting Firms in Shaanxi, China. J. Clean Prod. 2015, 108, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.Y.M.; Li, Y.L.; Crabbe, M.J.C.; Manta, O.; Shoaib, M. The Impact of Sustainability Awareness and Moral Values on Environmental Laws. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, L.; Sun, C. How does urban environmental legislation guide the green transition of enterprises? Based on the perspective of enterprises’ green total factor productivity. Energy Econ. 2022, 110, 106032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cao, C.; Gu, J.; Liu, T. A New Environmental Protection Law, Many Old Problems? Challenges to Environmental Governance in China. J. Environ. Law 2016, 28, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ite, A.; Ufot, U.; Ite, M.; Isaac, I.; Ibok, U. Petroleum Industry in Nigeria: Environmental Issues, National Environmental Legislation and Implementation of International Environmental Law. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2016, 4, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Gao, M. Study on the Energy-Saving and Emission-Reducing Effect of Environmental Regulation: Based on the Empirical Analysis of the Panel Quantile. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2017, 38, 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Shahzad, U.; Zhao, X. How environmental regulations affect the development of green finance: Recent evidence from polluting firms in China. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S. Policies for Enhancing Corporate Environmental Management: A Framework and an Applied Example. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.; Zhang, K.; Wei, W.; Ma, W.; Abedin, M.Z. The impact of green credit policy on enterprises’ financing behavior: Evidence from Chinese heavily-polluting listed companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.-Y.; Chen, Y.-Q.; Du, J.-G. The Forming Mechanism Research of Environmental Innovation Behavior of FDI Enterprises Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2018, 38, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Guo, Q.; Han, C.; Ahmad, N. Different Extent of Environmental Information Disclosure Across Chinese Cities: Contributing Factors and Correlation with Local Pollution. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 39, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Martínez, F.; Díaz-García, C.; González-Moreno, Á. Factors Promoting Environmental Responsibility in European SMEs: The effect on Performance. Sustainability 2016, 8, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tang, C.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y. How does public environmental supervision affect the industrial structure optimization? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 1485–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, S. Corporate Environmental Pressure from Community, Environmental Information Communication and Environmental Operating Performance. Soft Sci. 2018, 32, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; He, Q.; Shao, S.; Gao, J. Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations and Urban Environmental Governance: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 1296–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, M. Study on Interest Game and Allocation Mechanism in Allocation of China’s Environmental Management Right. Int. J. Environ. Prot. Policy 2017, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q. Influence of Media Supervision on Environmental Pollution Control. Ekoloji 2019, 28, 1493–1497. [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M. The Economic Relevance of Environmental Disclosure and its Impact on Corporate Legitimacy: An Empirical Investigation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2013, 24, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.D.; Zeng, S.X.; Zou, H.L.; Shi, J.J. The Impact of Corporate Environmental Violation on Shareholders’ Wealth: A Perspective Taken from Media Coverage. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 25, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, C.; Zhang, W. Lifting of Short Sale Constraint and the Quality of Environmental Information Disclosure: A Quasi-natural Experiment Based on Heavily Polluting Enterprises. China Soft Sci. 2017, 11, 116–130. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, J.-H.; Hofstetter, J.S.; Sarkis, J. Exploring Sub-suppliers’ Compliance with Corporate Sustainability Standards. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 112, 1971–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.-H.; Sarkis, J. Relationships Between Operational Practices and Performance Among Early Adopters of Green Supply Chain Management Practices in Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, S.L. Can consumers enforce environmental regulations? The role of the market in hazardous waste compliance. J. Regul. Econ. 2007, 31, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M.; Frieze, I.-H. Pollution Reduction Preferences of U.S. Environmental Managers: Applying Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W. Environmental Investment, Environmental Technology and Environmental Industry Development: Evidence from Environmental Listed Companies. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2013, 15, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Potoski, M.; Prakash, A. Green Clubs and Voluntary Governance: ISO 14001 and Firms’ Regulatory Compliance. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2005, 49, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yang, Q. An Empirical Study on Enterprises’ Environmental Behaviors and Their Influencing Factors Through Eco-industrial Parks Development in China. Manag. Rev. 2013, 25, 843–844. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, Y.; Fineinan, S.; Sims, D. Organizing and Organizations; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Lou, G. The Environmental Performance of Foreign Direct Investment Firms: The Case of Shanghai. China Econ. Q. 2014, 13, 515–536. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Wang, T.; Dai, J. The Impact of Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices on Firm Performance: An Empirical Study from China. J. Appl. Stat. Manag. 2017, 36, 693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Tian, D.; Xu, G. Meta-analysis on the Affecting Factors of Green Supply Chain Management Practices. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Wang, Y. Supervision Mechanism for Pollution Behavior of Chinese Enterprises Based on Haze Governance. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, C. The Effect of Public Participation on Environmental Governance in China–Based on the Analysis of Pollutants Emissions Employing a Provincial Quantification. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analysis of Mediating Effects: Method and Model Development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lihua, W.U.; Tianshu, M.A.; Yuanchao, B.I.A.N.; Sijia, L.I.; Zhaoqiang, Y.I. Improvement of regional environmental quality: Government environmental governance and public participation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137265. [Google Scholar]

| Scales | Number of Items | Cronbach’s α | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal factors in the supply chain | Internal Environmental Management (EM) | 5 | 0.869 | 0.713 | 0.825 |

| Enterprises’ interests (EI) | 5 | 0.861 | |||

| Characteristics of polluting enterprises (CPE) | 5 | 0.867 | |||

| External factors in the supply chain | Environmental legislation (EL) | 3 | 0.767 | 0.877 | |

| Environmental regulation (ER) | 3 | 0.856 | |||

| Public supervision of environment (PSE) | 3 | 0.820 | |||

| Environmental destructive behavior | Environmental violations (EV) | 4 | 0.926 | 0.963 | |

| Environmental penalties (EP) | 4 | 0.951 | |||

| Dimension | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal environmental management | EM1 | 0.63 | 0.869 | 0.879 | 0.597 |

| EM2 | 0.84 | ||||

| EM3 | 0.90 | ||||

| EM4 | 0.78 | ||||

| EM5 | 0.68 | ||||

| Enterprises’ interests | EI1 | 0.82 | 0.861 | 0.852 | 0.538 |

| EI2 | 0.85 | ||||

| EI3 | 0.69 | ||||

| EI4 | 0.61 | ||||

| EI5 | 0.67 | ||||

| Characteristics of polluting enterprises | CPE1 | 0.58 | 0.867 | 0.857 | 0.553 |

| CPE2 | 0.60 | ||||

| CPE3 | 0.82 | ||||

| CPE4 | 0.93 | ||||

| CPE5 | 0.73 | ||||

| Environmental legislation | EL1 | 0.69 | 0.767 | 0.771 | 0.530 |

| EL2 | 0.78 | ||||

| EL3 | 0.71 | ||||

| Environmental Regulation | ER1 | 0.66 | 0.856 | 0.866 | 0.688 |

| ER2 | 0.96 | ||||

| ER3 | 0.84 | ||||

| Public supervision of environment | PSE1 | 0.72 | 0.820 | 0.833 | 0.632 |

| PSE2 | 0.97 | ||||

| PSE3 | 0.66 | ||||

| Environment Violation | EV1 | 0.79 | 0.926 | 0.926 | 0.759 |

| EV2 | 0.79 | ||||

| EV3 | 0.95 | ||||

| EV4 | 0.94 | ||||

| Environment penalties | EP1 | 0.93 | 0.951 | 0.953 | 0.834 |

| EP2 | 0.85 | ||||

| EP3 | 0.96 | ||||

| EP4 | 0.91 |

| Fitting Indicators | CMIN/DF | RMR | GFI | AGFI | NFI | IFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion standard | <3 | <0.05 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | <0.08 |

| Full model | 1.956 | 0.152 | 0.791 | 0.752 | 0.839 | 0.914 | 0.913 | 0.068 |

| Path | Relationship | Path Coefficient | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER × GR→EV | − | −0.615 | 0.220 | −2.799 | 0.005 |

| ER × PSV→EV | + | 0.527 | 0.497 | 1.061 | 0.289 |

| GR × PSV→EV | − | −0.161 | 0.431 | −0.374 | 0.708 |

| ER × GR × PSV→EV | − | −0.219 | 0.150 | −1.465 | 0.143 |

| ER × GR→EP | + | 0.431 | 0.320 | 1.346 | 0.178 |

| ER × PSV→EP | − | −0.255 | 0.484 | −0.526 | 0.599 |

| GR × PSV→EP | + | 0.150 | 0.530 | 0.284 | 0.776 |

| ER × GR × PSV→EP | + | 0.660 | 0.345 | 1.914 | 0.056 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, T.; Du, J.; Boamah, K.B.; Xu, L.; Ma, M. The Internal and External Factors of Environmental Destructive Behavior in the Supply Chain: New Evidence from the Perspective of Brand-Name Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054605

Xie T, Du J, Boamah KB, Xu L, Ma M. The Internal and External Factors of Environmental Destructive Behavior in the Supply Chain: New Evidence from the Perspective of Brand-Name Products. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054605

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Tao, Jianguo Du, Kofi Baah Boamah, Lingyan Xu, and Mingyue Ma. 2023. "The Internal and External Factors of Environmental Destructive Behavior in the Supply Chain: New Evidence from the Perspective of Brand-Name Products" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054605

APA StyleXie, T., Du, J., Boamah, K. B., Xu, L., & Ma, M. (2023). The Internal and External Factors of Environmental Destructive Behavior in the Supply Chain: New Evidence from the Perspective of Brand-Name Products. Sustainability, 15(5), 4605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054605