Marketing Automation: How to Effectively Lead the Advertising Promotion for Social Reconstruction in Hotels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature and Theoretical Development

2.1. Customer Decision Process in Response to Hotel Franchise Promotion

2.2. AA-IDA Model

2.3. Hypotheses

3. Methods and Procedures

3.1. Study 1: Behavioral Experiment

3.1.1. Experiment Design

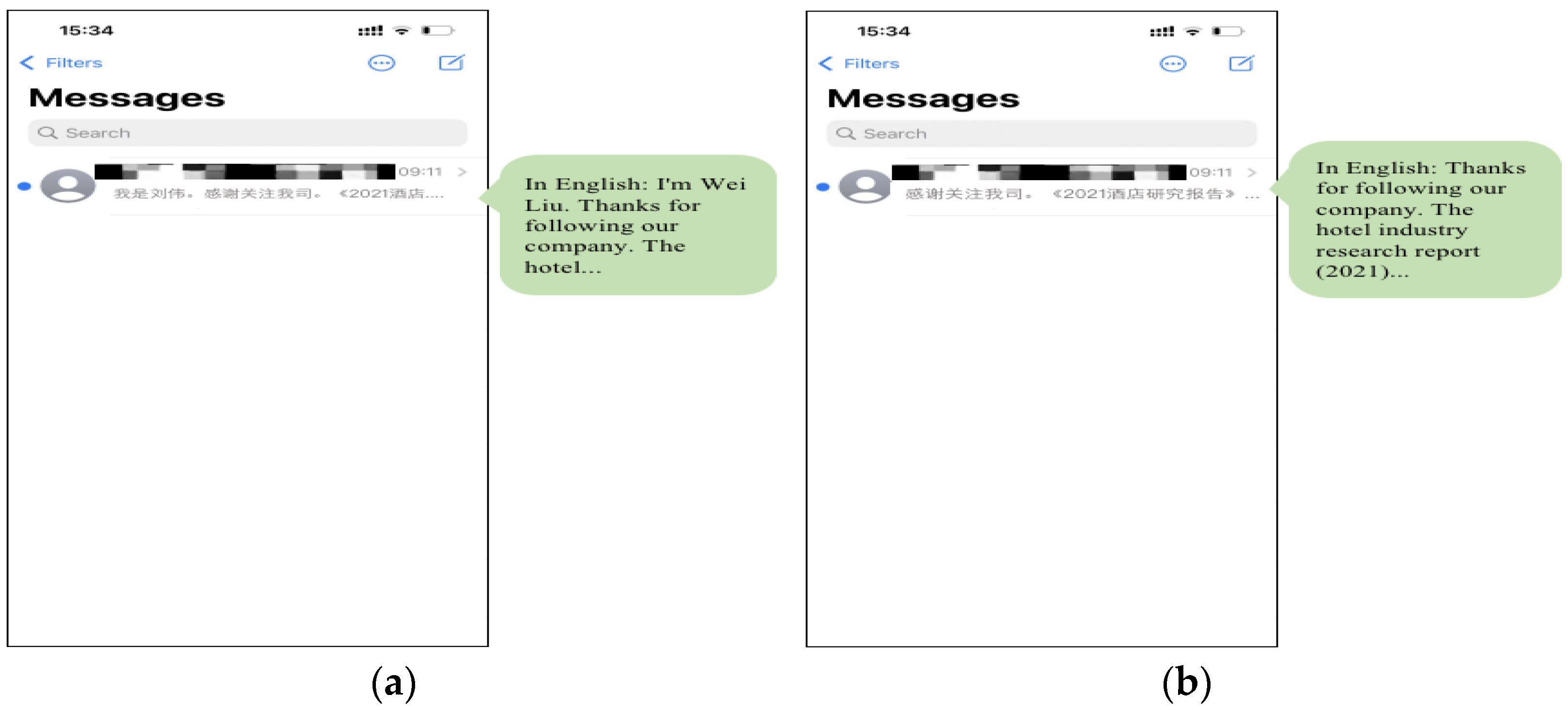

3.1.2. Procedure

3.1.3. Participants

3.2. Study 2: Field Experiment

3.2.1. Experiment Design

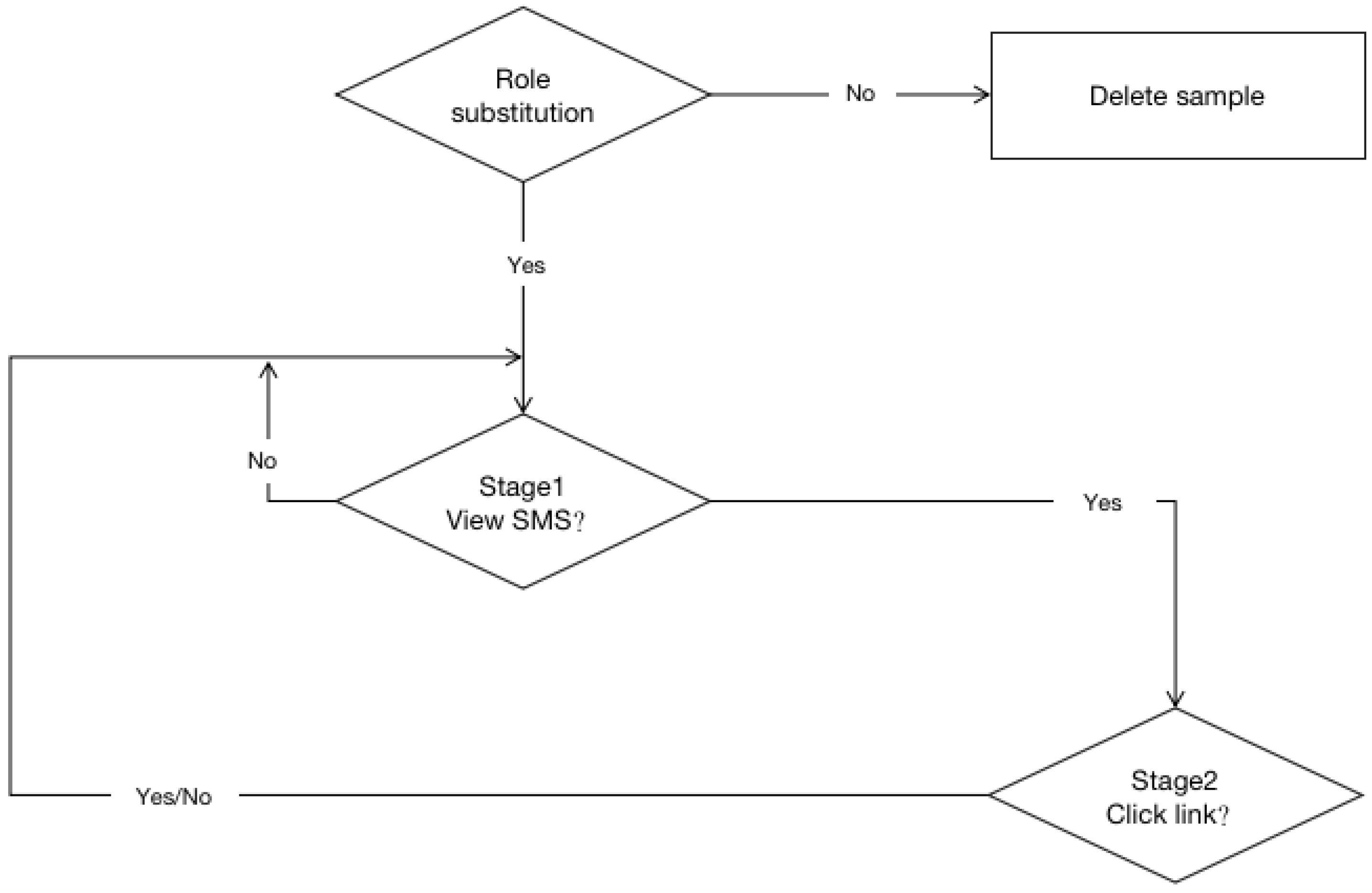

3.2.2. Procedure

3.2.3. Participants

4. Results

4.1. Results of Study 1: Behavioral Experiment

4.1.1. Advertising Exposure

ΔControlVars + εi

4.1.2. Advertising Conversion

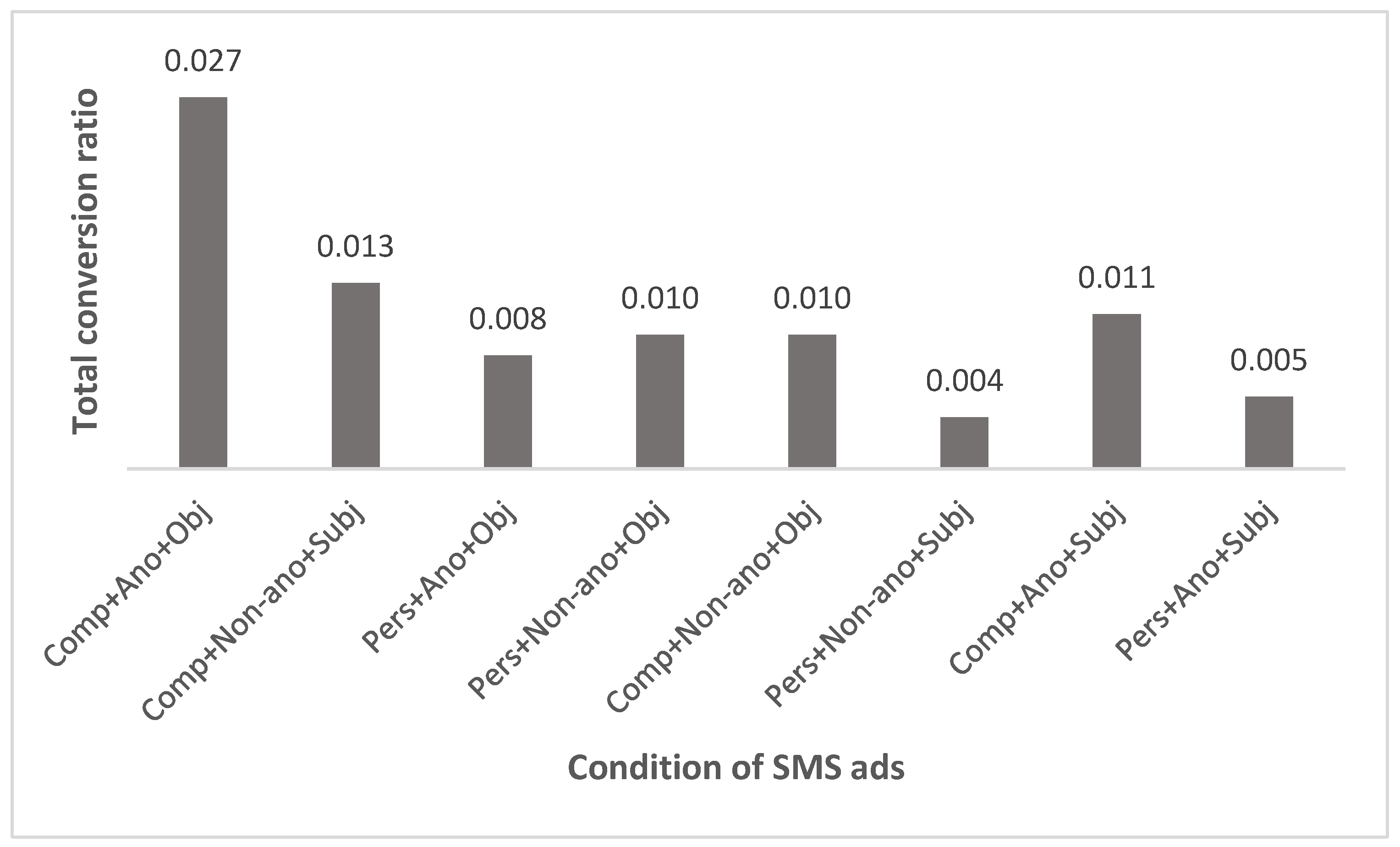

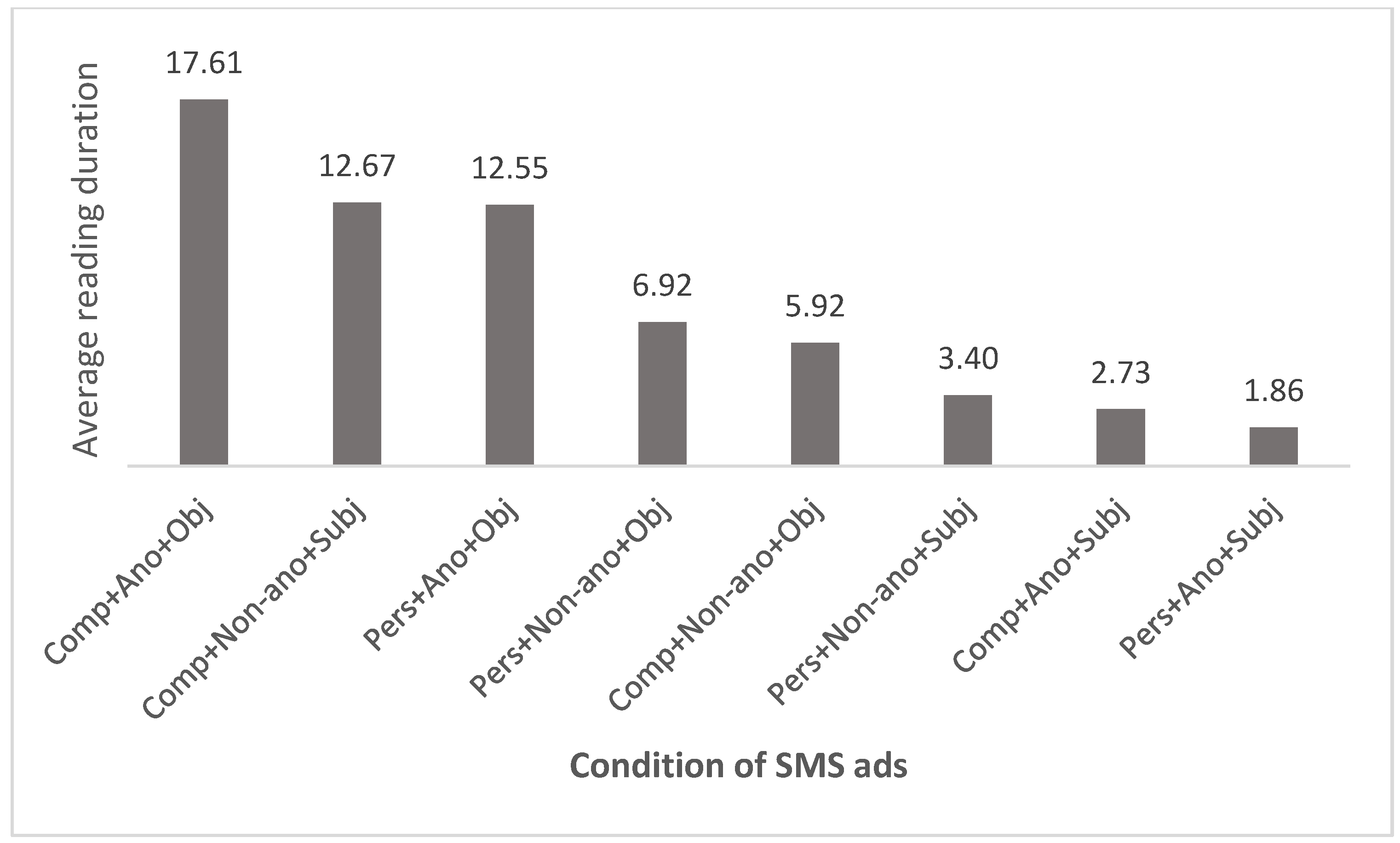

4.2. Results of Study 2: Field Experiment

5. General Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Applications

5.3. Conclusions

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sender Types | Anonymity Clues | Content Narratives | In Chinese (Origin) | In English (Translated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company Sender | Anonymity | Subjective narratives | 【人人宜咨询】感谢关注我司。《2021酒店研究报告》了解行业资讯,受到众多好评 https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 查看。退T | 【Renry Consulting】Thanks for following our company. The hotel industry research report (2021) has been released, which is well received by many people in the hotel industry. To obtain the industry information, click on https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 to view. T to unsubscribe |

| Objective narratives | 【人人宜咨询】感谢关注我司。《2021酒店研究报告》100余位大咖分享,80%好评 https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 查看。退T | 【Renry Consulting】Thanks for following our company. The hotel industry research report (2021) has been released, the industry experience of more than 100 specialists has been taught. The positive rating from industry insiders exceeds 80%. Click on https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 to view. T to unsubscribe | ||

| Non-anonymity | Subjective narratives | 【人人宜咨询】我是刘伟,感谢关注我司。《2021酒店研究报告》了解行业资讯,受到众多好评 https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 查看。退T | 【Renry Consulting】I’ m Wei Liu. Thanks for following our company. The hotel industry research report (2021) has been released, which is well received by many people in the hotel industry. To obtain the industry information, click on https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 to view. T to unsubscribe | |

| Objective narratives | 【人人宜咨询】我是刘伟,感谢关注我司。《2021酒店研究报告》100余位大咖分享,80%好评 https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 查看。退T | 【Renry Consulting】I’ m Wei Liu. Thanks for following our company. The hotel industry research report (2021) has been released, the industry experience of more than 100 specialists has been taught. The positive rating from industry insiders exceeds 80%. Click on https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 to view. T to unsubscribe | ||

| Person Sender | Anonymity | Subjective narratives | 感谢关注我司。《2021酒店研究报告》了解行业资讯,受到众多好评 https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 查看。 | Thanks for following our company. The hotel industry research report (2021) has been released, which is well received by many people in the hotel industry. To obtain the industry information, click on https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 to view. |

| Objective narratives | 感谢关注我司。《2021酒店研究报告》100余位大咖分享,80%好评 https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 查看。 | Thanks for following our company. The hotel industry research report (2021) has been released, the industry experience of more than 100 specialists has been taught. The positive rating from industry insiders exceeds 80%. Click on https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 to view. | ||

| Non-anonymity | Subjective narratives | 我是刘伟,感谢关注我司。《2021酒店研究报告》了解行业资讯,受到众多好评 https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 查看。 | I’ m Wei Liu. Thanks for following our company. The hotel industry research report (2021) has been released, which is well received by many people in the hotel industry. To obtain the industry information, click on https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 to view. | |

| Objective narratives | 我是刘伟,感谢关注我司。《2021酒店研究报告》100余位大咖分享,80%好评 https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 查看。 | I’ m Wei Liu. Thanks for following our company. The hotel industry research report (2021) has been released, the industry experience of more than 100 specialists has been taught. The positive rating from industry insiders exceeds 80%. Click on https://zndls.com/DTgIvUS6 to view. |

| Variables | Levels | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 136 | 53.30% |

| Female | 119 | 46.70% | |

| Age | Below 29 | 77 | 30.20% |

| 30–40 | 166 | 65.10% | |

| Above 41 | 12 | 4.70% | |

| Occupation | State enterprises and institutions | 34 | 13.30% |

| Private/Foreign Enterprises | 49 | 19.20% | |

| Civil servants | 14 | 5.50% | |

| Business owners | 71 | 27.80% | |

| Others | 87 | 34.20% | |

| Monthly Income (RMB) | Less than 15,000 | 53 | 20.80% |

| 15,001–50,000 | 193 | 75.70% | |

| More than 50,000 | 9 | 3.50% |

References

- Reyes-Menendez, A.; Saura, J.R.; Martinez-Navalon, J.G. The Impact of e-WOM on Hotels Management Reputation: Exploring TripAdvisor Review Credibility with the ELM Model. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 68868–68877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, K. This Report Analyses the Performance of Greater China’s Hotel Market Greater China Hotel Report. 2021. Available online: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/673/documents/en/greater-china-hotel-report-may-2021-8144.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Bühler, J.; Bick, M. From text messages to WhatsApp: Cultural effects on m-commerce service adoption in the UK and Russia. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2019, 17, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Lin, Y.C.; Yang, H.W. The effect of advertising on market share instability in the hotel industry. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, S.C. Do franchised chains advertise enough? J. Retail. 1999, 75, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, B.; Mattila, A.S.; O’Neill, J.W.; Kim, Y. Hotel rebranding and rescaling: Effects on financial performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2009, 50, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Mela, C.F.; Balseiro, S.R.; Leary, A. Online display advertising markets: A literature review and future directions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 556–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holverson, S.; Revaz, F. Perceptions of European independent hoteliers: Hard and soft branding choices. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, C.; Stephen, A.T. A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: Research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Lu, X.; Li, J. When and how to leverage e-commerce cart targeting: The relative and moderated effects of scarcity and price incentives with a two-stage field experiment and causal forest optimization. Inf. Syst. Res. 2019, 30, 1203–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Salleh, N.Z.M.; Al-Zahrani, S.A.; Khraiwish, A. Consumer Behaviour to Be Considered in Advertising: A Systematic Analysis and Future Agenda. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed; Alsharif, H.; Salleh, N.Z.M.; Ahmad, W.A.W.; Khraiwish, A. Biomedical Technology in Studying Consumers’ Subconscious Behavior. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. (IJOE) 2022, 18, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Josiassen, A.; Mattila, A.S.; Cvelbar, L.K. Does advertising spending improve sales performance? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 48, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Lin, Y.C. How do advertising expenditures influence hotels’ performance? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Song, H.J.; Lee, C.K.; Petrick, J.F. An integrated model of pop culture fans’ travel decision-making processes. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Ruan, W.J.; Jeon, Y.J.J. An integrated approach to the purchase decision making process of food-delivery apps: Focusing on the TAM and AIDA models. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Huang, Z.; Bao, J. A model of tourism advertising effects. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramphorn, S. How to use advertising to build brands: In search of the philosopher’s stone. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 48, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Schrier, T. Hierarchical effects of website aesthetics on customers’ intention to book on hospitality sharing economy platforms. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tsai, C.; Tang, T. Exploring Advertising Effectiveness of Tourist Hotels’ Marketing Images Containing Nature and Performing Arts: An Eye-Tracking Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Green, C.; Fairley, S. Investigation of the use of eye tracking to examine tourism advertising effectiveness. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 19, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Chan, J. “What is beautiful we book”: Hotel visual appeal and expected service quality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1788–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, B.M.; Robson, S.K.A. Understanding Consumers’ Inferences from Price and Nonprice Information in the Online Lodging Purchase Decision. Serv. Sci. 2016, 8, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomcharoenchaikit, K. Exploring Sharing Experiences and Satisfaction during Staying with Hostels in Bangkok, Thailand. 2018. Available online: https://archive.cm.mahidol.ac.th/handle/123456789/2718 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Sama, R. Impact of Media Advertisements on Consumer Behaviour. J. Creat. Commun. 2019, 14, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Awais-E-Yazdan, M.; Mushtaque, I.; Deng, L. The Impact of Technology Adaptation on Academic Engagement: A Moderating Role of Perceived Argumentation Strength and School Support. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Singh, S.; Sinha, P. Multimedia tool as a predictor for social media advertising—A YouTube way. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 18557–18568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortenberry, J.L.; McGoldrick, P.J. Do Billboard Advertisements Drive Customer Retention?: Expanding the “AIDA” Model to “AIDAR”. J. Advert. Res. 2020, 60, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Liu, M.; Xu, J.; Li, S.; Cao, J. Understanding the influence of sensory advertising of tourism destinations on visit intention with a modified AIDA model. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, E.K. The Psychology of Selling and Advertising; McGraw-Hill book Company, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, C.H.; Wang, Y.S.; Li, H.T.; Lin, S.Y. The effect of information presentation modes on tourists’ responses in Internet marketing: The moderating role of emotions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 1018–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepaniuk, K. Blog content management in shaping pro recreational attitudes. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, N.V. Determinants of Desired Exposure to Interactive Advertising. Doctor Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 1996. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/dc5a39ea810e63d7c1eac5fee7f38623/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Mostafa, R.B.; Kasamani, T. Antecedents and consequences of chatbot initial trust. Eur. J. Mark. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Park, S. What makes a useful online review? Implication for travel product websites. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M.; Ekinci, Y. Do online hotel rating schemes influence booking behaviors? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 49, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duverger, P. Curvilinear Effects of User-Generated Content on Hotels’ Market Share. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinger, A.; Kleijnen, M. Coupons going wireless: Determinants of consumer intentions to redeem mobile coupons. J. Interact. Mark. 2008, 22, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.S.; Park, S.B.; Oh, J. An examination of factors influencing consumer adoption of short message service (SMS). Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, A.M. The Effects of SMS Advertising on Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention: An Experimental Study on University Students. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Elektron. Derg. 2018, 6, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Andrews, M.; Fang, Z.; Phang, C.W. Mobile targeting. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 1738–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappey III, R.J.; Woodside, A.G. Consumer responses to interactive advertising campaigns coupling short-message-service direct marketing and TV commercials. J. Advert. Res. 2005, 45, 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Dong, Z.; Shi, X. Effect of homebuyer comment on green housing purchase intention—Mediation role of psychological distance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 568451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Hill, J.T. Utilitarian and hedonic perceptions of short message service mobile marketing. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2013, 11, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Arya, V.; Siddiqui, M.Q. Does SMS advertising still have relevance to increase consumer purchase intention? A hybrid PLS-SEM-neural network modelling approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounder, N.; Narayan, J.; Naidu, S.; Greig, T. Consumers perceived advertising value and attitude towards SMS advertisements in developing countries: The Case of Fiji. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2021, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M.; Luo, X.; Fang, Z.; Ghose, A. Mobile ad effectiveness: Hyper-contextual targeting with crowdedness. Mark. Sci. 2016, 35, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossos, D.A.; Giaglis, G.M.; Vlachos, P.A.; Zamani, E.D.; Lekakos, G. Consumer responses to SMS advertising: Antecedents and consequences. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2013, 18, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittala, R. Registering for incentivized mobile advertising: Discriminant analysis of mobile users. Int. J. Mob. Mark. 2011, 6, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T. An empirical examination of the determinants of mobile purchase. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2013, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, S.; Phau, I.; Jamieson, K.; Shimul, A.S. Investigating the drivers of consumer acceptance and response of SMS advertising. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseeh, H.I.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Pentecost, R.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Arli, D.; Weaven, S. A meta-analytic review of mobile advertising research. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshra, D.; Beshir, N. Effect of consumer attitude towards sms advertising and demographic features on egyptian consumers buying decision. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 7, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, I.; Rasel, K.A.; Kobra, K.; Noor, F.; Zayed, N.M. Customers’ attitude toward SMS advertising: A strategic analysis on mobile phone operators in Bangladesh. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 19, 1–7. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/8c6561c4f25a5faef13dbf0450ac8817/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=38745 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Lin, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Z. Impact of the content characteristic of short message service advertising on consumer attitudes. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2014, 42, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Bhatti, A.; Leonardo Cavaliere, L.P.; Javaid, A. Impact of mobile advertising on consumers attitude. Ilkogr. Online 2021, 20, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Ekinci, Y.; Can, A.S.; Murray, J.C. Effectiveness of message framing in changing COVID-19 vaccination intentions: Moderating role of travel desire. Tour. Manag. 2022, 90, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, F.C.; Teng, C.I. Carefulness matters: Consumer responses to short message service advertising. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2016, 20, 525–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muk, A.; Chung, C. Applying the technology acceptance model in a two-country study of SMS advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.H.; Sutanto, J.; Phang, C.W.; Gasimov, A. Using personal communication technologies for commercial communications: A cross-country investigation of email and SMS. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsons, M.G. Relationship-based e-commerce: Theory and evidence from China. Inf. Syst. J. 2008, 18, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, A.S.M.; Branisso, D.S.P. In the right place at the right time: Opportunities for mobile location-based marketing research. In Proceedings of the CLAV 2020, Varadero, Cuba, 29–30 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, P. Digital marketing: A framework, review and research agenda. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2017, 34, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bies, S.M.; Bronnenberg, B.J.; Gijsbrechts, E. How push messaging impacts consumer spending and reward redemption in store-loyalty programs. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 877–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divisekera, S.; Nguyen, V.K. Determinants of innovation in tourism evidence from Australia. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.J.; Dewan, S.; Ho, Y.C. Distance and local competition in mobile geofencing. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 1421–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaryan, L.; Fredman, P. Natural amenities and the regional distribution of nature-based tourism supply in Sweden. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Explanatory Variables | Dependent Variables—Message Acceptance | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| Constant | −0.255 (0.402) | −0.373 (0.392) | |

| Anonymity clues | −0.095 (0.142) | 1 | |

| Sender types | −0.31 * (0.143) | 1 | |

| Anonymity clues * Sender types | −0.357 ** (0.16) | ||

| Gender | 0.227 (0.154) | 0.229 (0.154) | 1.155 |

| Age | 0.051 (0.095) | 0.052 | 1.535 |

| Income | 0.266 *** (0.081) | 0.265 *** (0.081) | 1.499 |

| Chi-square | 23.627 *** | 23.369 *** | |

| Log likelihood | 1131.351 | 1131.609 | |

| HL test (Prob > chi-squared) | 0.875 | 0.349 | |

| Explanatory Variables | Dependent Variables—Advertising Conversion | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Constant | −1.381 *** (0.364) | −0.626 * (0.298) | −0.59 * (0.297) |

| Anonymity clues | 0.479 ** (0.184) | ||

| Sender types | 0.375 * (0.184) | ||

| Content narratives | 0.594 ** (0.19) | ||

| Anonymity clues * Sender types | 0.532 * (0.225) | ||

| Anonymity clues * Sender types * Content narratives | −0.778 ** (0.294) | ||

| Gender | 0.402 * (0.205) | 0.417 * (0.202) | 0.437 * (0.202) |

| Age | 0.006 (0.124) | −0.008 (0.121) | −0.02 (0.121) |

| Income | 0.464 *** (0.108) | 0.426 *** (0.105) | 0.41 * (0.104) |

| Chi-square | 59.179 *** | 46.069 *** | 44.244 *** |

| Log likelihood | 690.463 | 703.573 | 705.398 |

| HL test (Prob > chi-squared) | 0.63 | 0.624 | 0.083 |

| Explanatory Variables | Dependent Variables—Total Acceptance |

|---|---|

| Constant | −5.113 *** (0.219) |

| Anonymity clues | −0.347 (0.188) |

| Sender types | 0.833 *** (0.201) |

| Content narratives | 0.49 ** (0.191) |

| Chi-square | 28.861 *** |

| Log likelihood | 1270.179 |

| HL test (Prob > chi-squared) | 0.164 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, B.; Gao, L. Marketing Automation: How to Effectively Lead the Advertising Promotion for Social Reconstruction in Hotels. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4397. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054397

Sun X, Li Y, Guo B, Gao L. Marketing Automation: How to Effectively Lead the Advertising Promotion for Social Reconstruction in Hotels. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4397. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054397

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xue, Yuhao Li, Bo Guo, and Li Gao. 2023. "Marketing Automation: How to Effectively Lead the Advertising Promotion for Social Reconstruction in Hotels" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4397. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054397

APA StyleSun, X., Li, Y., Guo, B., & Gao, L. (2023). Marketing Automation: How to Effectively Lead the Advertising Promotion for Social Reconstruction in Hotels. Sustainability, 15(5), 4397. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054397