Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Sustainable Consumption

2.2. Factors Influencing Sustainable Dietary Choices

2.3. Motivations and Aspirations Underlying Collective Forms of Conscious and Socially Responsible Food Consumption

3. Materials and Methods

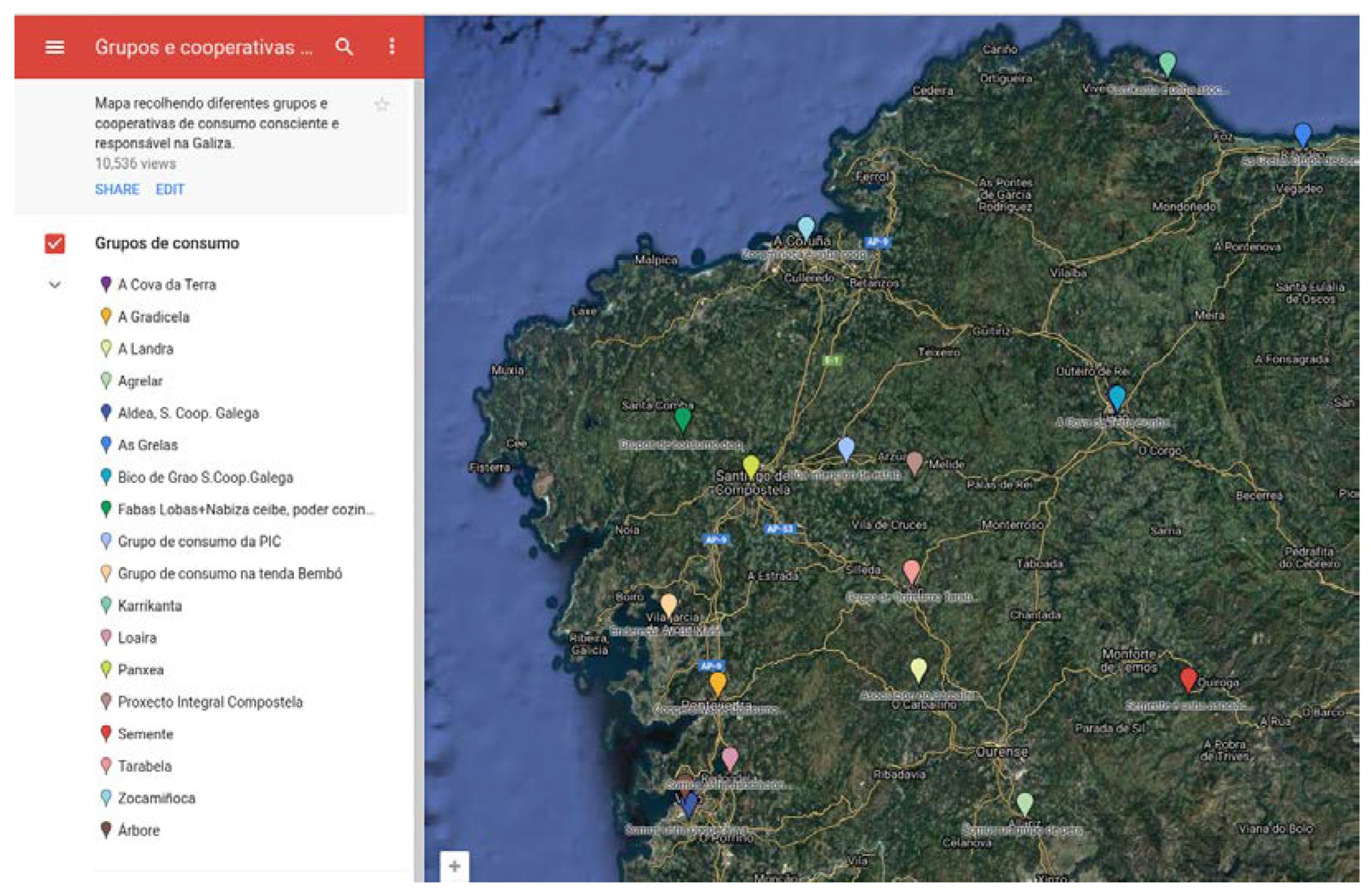

3.1. Case Study Description

3.2. Research Objectives, Methods, and Sample Description

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

4. Results

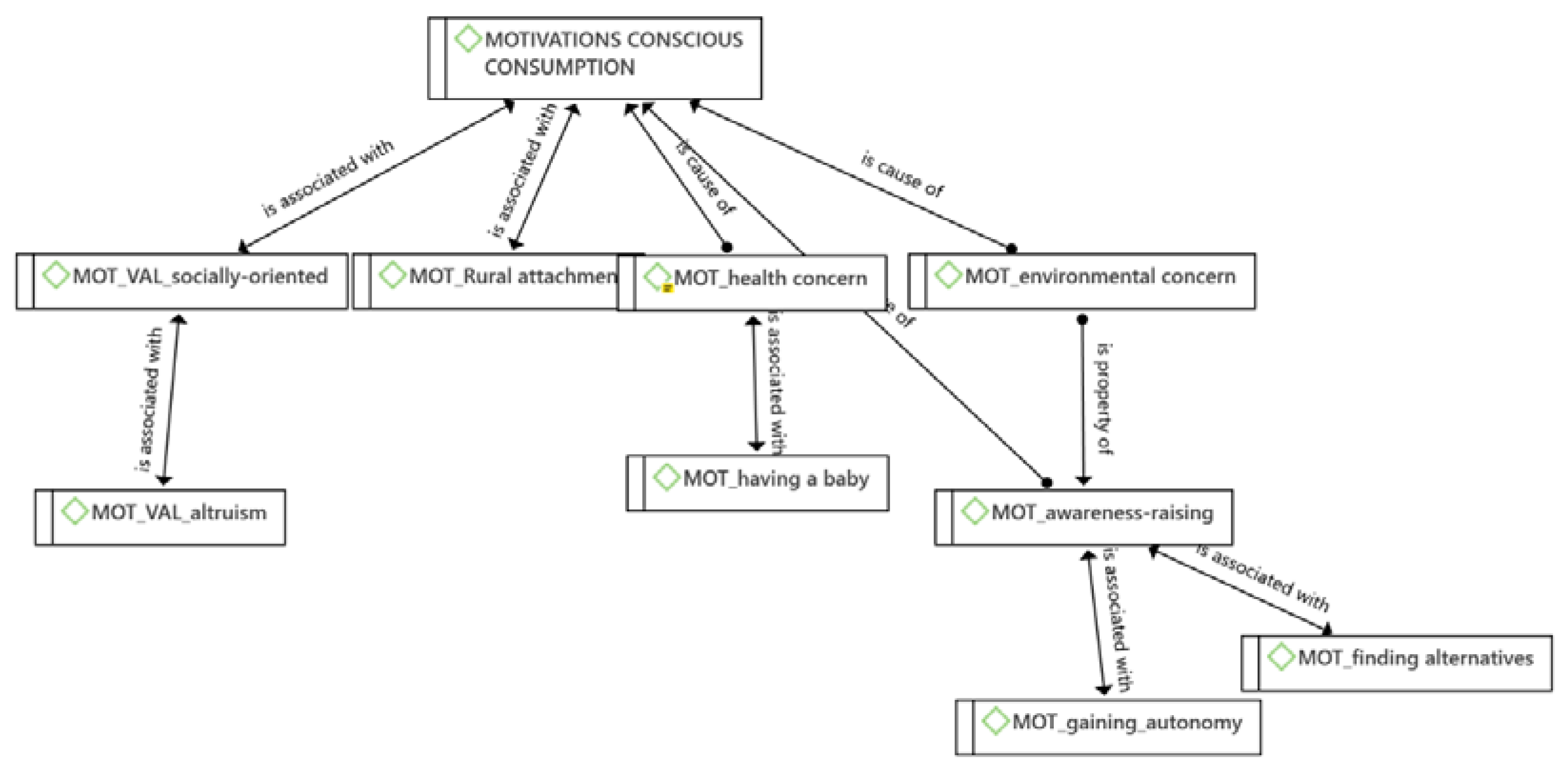

4.1. Underlying Motivations to Organic and Sustainable Food Consumption

4.1.1. Environmental Concern

“(Organic food relates to) supporting local markets, local producers, local products, not moving food from one place to another on the planet. It is ridiculous! We want to support organic food, but within a sustainable social frame. Not the organic food that is sold in Carrefour or whatever. I mean responsibility in the entire system” (quote: Fátima, Millo Miúdo).

4.1.2. Health and Personal Wellbeing

“Zocamiñoca’s partner profile is a person who decides to be join Zocamiñoca for more reasons than only food needs. They are people who care about their health and who like to eat healthy. They are usually active people, which maintain a less sedentary lifestyles than regular people” (quote: Lois, Zocamiñoca).

4.1.3. Altruistic and Socially Oriented Values

“Social change is possible step by step, working every day. Not saying “we are going to make the revolution” and then you find that nothing has changed, which is what has happened throughout history. Indeed, there have been no structural changes, because we have never challenged the core parts of the system, just only the most superficial ones. Consumption is the basis. What we eat is what we are. What we walk, what we breathe, what we are and what we do “(quote: Fátima, Millo Miúdo).

4.1.4. Attachment to Rural

“I have always been in contact with the rural, although I live in the city. I have always liked it, I always have appreciated, I have always felt comfortable, and it has seemed like a place to preserve” (quote: Fabio, Zocamiñoca).

“I always valued the issue of food, and I always gave a lot of value to the people who work in agriculture, who are actually feeding us. In fact, after working in a garden, knowing what it is, planting your food… for me it was particularly important the dignity of the people who are working in the field. It was something highly relevant in the project” (quote: Xulia, Zocamiñoca).

4.1.5. Awareness Raising

“There is a turning point. In 2000, when I was still finishing my degree, I had not any political position, I entered contact with people who were concerned about these issues. Issues like the Louvain report, issues that happened in 2000 did make me open the eyes a bit (…); I took that political leap when I met people from social movements, antimilitarism, anarchist unions. And, above all, I remember the anti-globalization movement demonstrations in Barcelona and Genova. That meant a turning point for me” (quote: Alba, Zocamiñoca).

“I lived in London before I moved to here. In London, so I did not belong to any particular cooperative, but I did go to farms that had that, this week’s orders, order baskets, apart from that I was interested in all these kinds of things, because I saw a little of it. that there were, from organic markets to things a little bigger, to smaller things like this” (quote: Carlos, Zocamiñoca).

“Some people join the group because of their children. They do not consume organic food, but their children do. They come for their children. This looks a total incoherence, but they are moved by these reasons” (quote: Rocío, Semente).

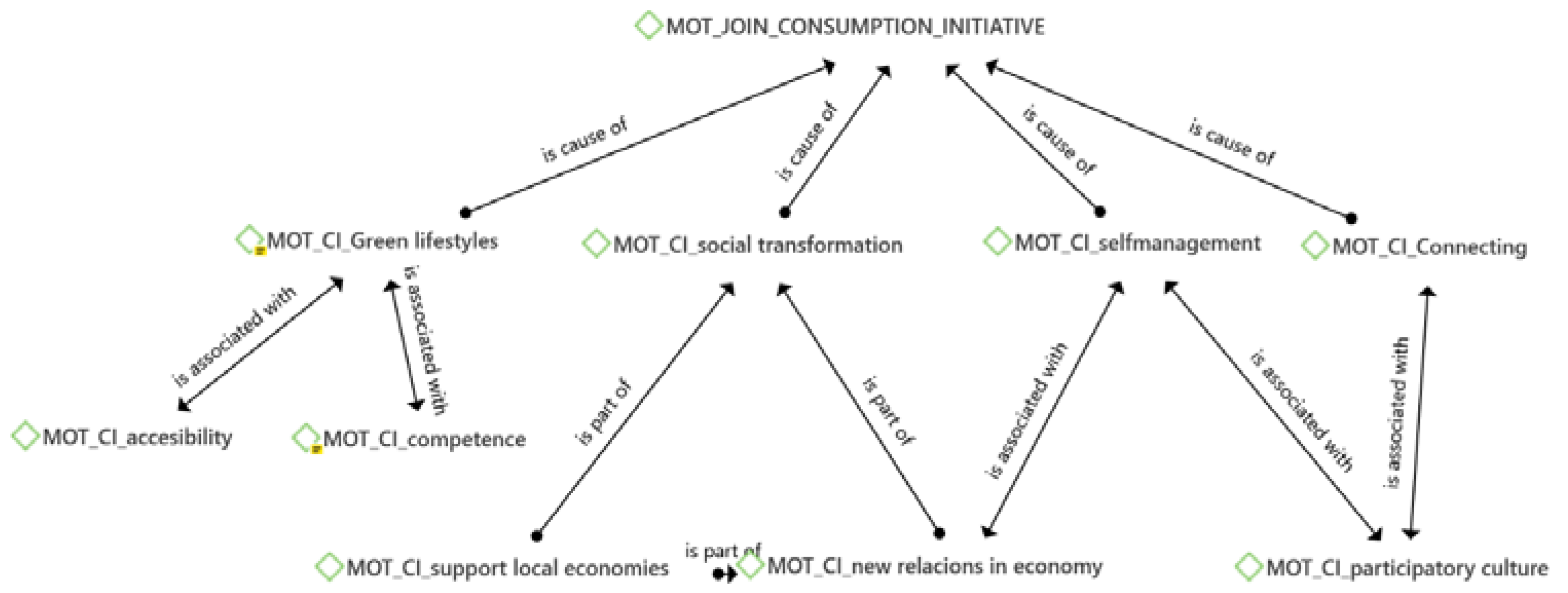

4.2. Motivations for Joining a Local Conscious and Responsible Consumption Initiative

4.2.1. Perception of Consumption Initiatives as Spaces That Facilitate Green Lifestyles

“This cooperative was born as an attempt to make accessible in one way or another the ecological product to people” (quote: Olivia, Aldea).

4.2.2. Accessibility, Availability, and Price

“This group began with the desire to obtain organic products that there were not, except in specialized diet stores, which was very expensive” (quote: Breixo, A Gradicela).

“(Q) Why did you join Semente? (A): Because it seems important to me to consume local products, to support people, farmers from here, because of the ecological footprint. And I also understand that prices are cheaper. It suits me very well. It is good. If I compare what costs what you buy in the market and in the food group, I save money, that is great” (quote: Sara, Semente).

4.2.3. Sociopolitical Ambitions

“A society that belongs to everyone, in which wealth must go for the benefit of society, which contrasts with capitalism, which is a form of accumulation by possession in few hands” (quote: Antón, Árbore).

4.2.4. Fostering Local Economies and New Relations in Economy

“I joined the group with the idea of changing the world, “making the revolution” one could say (…) My basic motivation is political. I needed to participate in social groups that tried to transform the reality we live in. That was why I joined the group. Trying to engage in collective work” (quote: Victor, Agrelar).

4.2.5. Self-Management and Autonomy

“From an economic point of view, we must set up structures that are ours. In which we decide. It cannot be that democracy is political, but in the economic part, the economy is in the hands of few guys who decide everything. Because if the citizens do not decide in the economy, what kind of democracy is that? And if there are projects like this, or different, that is where you decide in the economy” (quote: Antón, Arbore).

“In my case, I am aligned with the self-management philosophy of these groups. I was in the scouts Before, which was a very self-managed group, but very pyramidal. Food coops are not hierarchical structures, which interests me the most. That the tomatoes are organic is fine, it is important, but that (self-management) depends on each group and each person (…). The step of entering these (consumer) groups was more related to looking for another type of participation, different from the one I had experienced, not so hierarchical” (quote: Alba, Zocamiñoca).

4.2.6. Satisfaction of Affective or Relational Needs: Connectedness with Like-Minded People

“I needed to participate in some social group that tried to transform the social reality we live from. That was why I joined. To try to do collective work. Here in the town, I felt alone (laughs), trying to do with own garden but without… I was not even capable of producing for my own consumption, or of doing anything else. So that would be the main motivation to join the group” (quote: Victor, Agrelar)

“This is a project to transform ourselves as well. We want the people who enter here to learn to function differently” (quote: Xulia, Zocamiñoca)

“It is an opportunity to explore or promote other things that you do not like about society in general and say, because we have the opportunity to be consistent and to try to work differently. This relates to the culture of the group. The issue of allowing us to disagree, allowing doubts to be welcomed” (quote: Gael, Zocamiñoca)

“It has to do with conscious consumption. On the one hand, if there are fair trade products, I know that labor rights are respected. We can trace it. On the other hand, eating organic food means that nature is respected, cared, the principles of organic farming are respected, as opposed to industrial agriculture. I intake products that are better for my health” (quote: Tomás, Árbore)

“We are talking about three spheres here. First, the personal sphere, in terms of the type of food I want to eat; There is the social level of what kind of employment I want to promote. And third, there is the local sphere, what economic model do I promote and want to support” (quote: Brais, Zocamiñoca)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Policy and practical implications

- Study limitations and future research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Assembly, UN General. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1. 21 October 2015. Available online: www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Vita, G.; Hertwich, E.G.; Stadler, K.; Wood, R. Connecting global emissions to fundamental human needs and their satisfaction. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 014002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, P.; Jacobs, N.; Villa, V.; Thomas, J.; Bacon, M.H.; Vandelac, L.; Schlavoni, C. A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045; IPESFOOD and ETC Group, 2021. Available online: https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/LongFoodMovementEN.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- García-Juanatey, A. Reconciling human rights and the environment: A proposal to integrate the right to food with sustainable development in the 2030 development agenda. J. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 2018, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R.E. “Energy-Smart” Food for People and Climate: Issue Paper; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2011; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i2454e/i2454e.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Gasper, D.; Shah, A.; Tankha, S. The framing of sustainable consumption and production in SDG 12. Glob. Policy 2019, 10, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Whitmarsh, L.; Gatersleben, B.; O’Neill, S.; Hartley, S.; Burningham, K.; Sovacool, B.; Barr, S.; Anable, J. Placing people at the heart of climate action. PLOS Clim. 2022, 1, e0000035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mira, R.; Dumitru, A. Green Lifestyles, Alternative Models and Upscaling Regional Sustainability; GLAMURS Final Report; Instituto Xoan Vicente Viqueira: A Coruña, Spain, 2017; Available online: http://www.people-environment-udc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/revista_glamurs_bj.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Papaoikonomou, E.; Alarcón, A. Revisiting Consumer Empowerment: An Exploration of Ethical Consumption Communities. J. Macromarketing 2017, 37, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IISD. Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption; The International Institute for Sustainable Development: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, T.; Polhill, G.; Colley, K.; Carrus, G.; Maricchiolo, F.; Bonaiuto, M.; Bonnes, M.; Dumitru, A.; García-Mira, R. Transmission of pro-environmental norms in large organizations. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 19, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. A review of sustainable consumption (2000 to 2020): What we know and what we need to know. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. Int. Strat. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Spruyt, A.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Van Lippevelde, W.; De Steur, H.; Verbeke, W. Environmentally Sustainable Food Consumption: A Review and Research Agenda from a Goal-Directed Perspective. Front. Psych. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piligrimienė, Ž.; Žukauskaitė, A.; Korzilius, H.; Banytė, J.; Dovalienė, A. Internal and external determinants of consumer engagement in sustainable consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastran, M.M.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J.; Blake, C.; Devine, C.M. Eating routines. Embedded, value based, modifiable, and reflective. Appetite 2009, 52, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, S. Social norms and their influence on eating behaviours. Appetite 2015, 86, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Maroño, N.; Rodríguez-Arias, A.; Dumitru, A.; Lema-Blanco, I.; Guijarro-Berdiñas, B.; Alonso-Betanzos, A. How Agent-based modeling can help to foster sustainability projects. Proc. Comp. Sci. 2022, 207, 2546–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema Blanco, I.; Dumitru, A. Theoretical Framework for the Definition of Locally Embedded Future Policy Scenarios; Deliverable 5.1 (Report); SMARTEES Project. 2019. Available online: https://local-social-innovation.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/SMARTEES-D5.1_Policy_Framework_R1.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Dumitru, A.; Lema Blanco, I.; Albulescu, P.; Antosz, P.; Bouman, L.; Colley, K.; Craig, T.; Jager, W.; Macsinga, I.; Meskovic, E.; et al. Policy Recommendations for Each Cluster of Case-Studies. Insights from Policy Scenario Workshops. Deliverable 5.2; SMARTEES Project. 2021. Available online: https://local-social-innovation.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Deliverables/D5.2_final__1_.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Gifford, R.D.; Chen, A.K. Why aren’t we taking action? Psychological barriers to climate-positive food choices. Clim. Change 2017, 140, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. Organic food consumption in Poland: Motives and barriers. Appetite 2016, 105, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Trade Association. US. Families’ Organic Attitudes and Beliefs 2016 Tracking Study; OTA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chekima, B.; Igau, A.; Wafa, S.A.W.S.K.; Chekima, K. Narrowing the gap: Factors driving organic food consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B.; Chekima, K.; Chekima, K. Understanding factors underlying actual consumption of organic food: The moderating effect of future orientation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 74, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Frisch, A.S.; Kalof, L.; Stern, P.C.; Guagnano, G.A. Values and Vegetarianism: An Exploratory Analysis. Rural Sociol. 1995, 60, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: A panel study. J. Eco. Psych. 2002, 23, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, R.A.; Rodríguez, M.J.G.; Rüdiger, K. Estudio comparativo de la producción y consumo de alimentos ecológicos en España y Alemania. Rev. Esp. Est. Agros. Pesq. 2019, 254, 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, J.; Scalco, A.; Craig, T. Social Influence and Meat-Eating Behaviour. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.C.; Reynolds, T.J. (Eds.) Understanding Consumer Decision Making: The Means-End Approach to Marketing and Advertising Strategy; Routledge: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulos, C.; Krystallis, A.; Ness, M. Wine produced by organic grapes in Greece: Using Means-End Chains analysis to reveal organic buyers’ purchasing motives in comparison to the non-buyers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2003, 14, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoli, R.; Naspetti, S. Consumer motivations in the purchase of organic food: A means-end approach. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, G.; Ivanova, D.; Dumitru, A.; García-Mira, R.; Carrus, G.; Stadler, K.; Krause, K.; Wood, R.; Hertwich, E.G. Happier with less? Members of European environmental grassroots initiatives reconcile lower carbon footprints with higher life satisfaction and income increases. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 60, 101329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Ecological citizenship, and sustainable consumption: Examining local organic food networks. J. Rural. Stud. 2006, 22, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoll, F.; Specht, K.; Opitz, I.; Siebert, R.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I. Individual choice or collective action? Exploring consumer motives for participating in alternative food networks. Int. J. Cons. Stud. 2018, 42, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeurwaerdere, T.; De Schutter, O.; Hudon, M.; Mathijs, E.; Annaert, B.; Avermaete, T.; Joachain, H.; Vivero, J.L. The governance features of social enterprise and social network activities of collective food buying groups. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A.; Lema-Blanco, I.; Kunze, I.; García-Mira, R. The Slow Food Movement, A Case-Study Report; TRANSIT Project. 2016. Available online: http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/content/original/Book%20covers/Local%20PDFs/193%20Slowfood_complete_report16-03-2016.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Lema-Blanco, I.; García-Mira, R.; Muñoz Cantero, J.M. Las iniciativas de consumo responsable como espacios de innovación comunitaria y aprendizaje social. Rev. Est. Investig. Psic. Educ. 2015, 14, 14-028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema Blanco, I. Educación Ambiental y Participación Pública: Análisis de los Procesos Participativos “Bottom-Up” Como Instrumentos de Aprendizaje para la Transformación Social (Environmental Education and Public Participation: Analysis of Bottom-Up Participatory Processes as Learning Instruments for Social Transformation). Ph.D. Dissertation, University of A Coruña, A Coruña, Spain, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2183/30088 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introduction to Qualitative Methods; Book Print: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. 2022. Available online: https://atlasti.com (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski, G.; Malinowska, M.; Kucharska, B.; Kucia, M.; Kolny, B. Sustainable development as a factor differentiating consumer behavior. Case Pol. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 934–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S.; Foster, C. Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour: Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pel, B.; Lema-Blanco, I.; Dumitru, A. WP4 Case Study Report: RIPESS; TRANSIT Project. 2017. Available online: http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/content/original/Book%20covers/Local%20PDFs/296%20RIPESSreportFINAL_211217.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Buerke, A.; Straatmann, T.; Lin-Hi, N.; Müller, K. Consumer awareness and sustainability-focused value orientation as motivating factors of responsible consumer behavior. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2017, 11, 959–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer Attitude-Behavior Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrazak, S.; Quoquab, F. Exploring consumers’ motivations for sustainable consumption: A self-deterministic approach. J. Int. Cons. Mark. 2018, 30, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Sustainable consumption. In Handbook of Sustainable Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 279–290. [Google Scholar]

| Typology | Name of the Initiative | Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperative with a store open to the public | Árbore (Vigo, Pontevedra) | 3 |

| Aldea (Vigo, Pontevedra) | 3 | |

| Cooperative with a store (only for associates) | Zocamiñoca (A Coruña) | 11 |

| Non-profit organization | Semente (Ourense) | 2 |

| Millo Miúdo (Oleiros, Coruña) | 4 | |

| Consumers’ group | Agrelar (Allariz, Ourense) | 1 |

| A Gradicela (Pontevedra) | 1 |

| Category | Description | Groundedness and Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental concern | Environmental concern about environmental risks, climate emergency, and impact of food system. | G: 41; F: 17 |

| Health and personal wellbeing | Desire to consume healthy and organic food (free of pesticides or GMOs) for personal and your family acquires a priority role. | G: 30; F: 17 |

| Altruism and socially oriented values | Altruism concerns, desire to improve the lives of those who are in disadvantaged situations. Socially oriented values are aligned with solidarity and social justice, building new types of relations between both the Global North and South. | G: 19; F: 9 |

| Attachment to rural | Sense of attachment to rural areas dedicated to primary sector of economy; and the desire to dignify small farmers/producers and sustain (Galician) traditional lifestyles. | G: 9; D: 2; F: 5 |

| Awareness raising | Awareness-rising due to an event or personal experience that acts as a trigger for a change in individual consumption styles and that understands eating as an essential part of a set of desirable pro-environmental behaviors. | G: 24; F: 9 |

| Category | Description | Groundedness and Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Green lifestyles | Identification of the CRCI as an enabling space for climate-friendly, fair, and ethical consumption. | G:31; F: 20 |

| Accessibility | Accessibility, availability, and affordability with respect to environmentally and socially responsible food | G: 34; F: 16 |

| Social transformation | Sociopolitical ambitions for social transformation. Desire for been involved in sociopolitical and/or socially transformative movements | G: 42; F: 13 |

| Support local economies | Support locally based economic alternatives based on the articulation of short food supply chains and foster new types of relations in economy | G: 27; F: 14 |

| New relations in economy | New relationship models in the economic context, fostering models of prosumerism and co-responsibility in the food system | G: 47; F: 15 |

| Self-management | Need for autonomy and control over consumption and ambitions related to self-management and gaining independence in economy | G: 36; F: 12 |

| Connectedness | Affective or relational needs: connecting with people who share common principles and values | G: 11; F: 8 |

| Competence | Individual’s belief in his or her ability to accomplish a desired behavior | G: 8; F: 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lema-Blanco, I.; García-Mira, R.; Muñoz-Cantero, J.-M. Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054111

Lema-Blanco I, García-Mira R, Muñoz-Cantero J-M. Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054111

Chicago/Turabian StyleLema-Blanco, Isabel, Ricardo García-Mira, and Jesús-Miguel Muñoz-Cantero. 2023. "Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054111

APA StyleLema-Blanco, I., García-Mira, R., & Muñoz-Cantero, J.-M. (2023). Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network. Sustainability, 15(5), 4111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054111