1. Introduction

The Chinese government has made significant efforts towards reducing poverty through targeted education services, integrated industrial development services, transfer employment and the relocation of industries in inhospitable areas. From 2013 to 2020, there has been a decrease in poverty levels in rural China, as shown in

Figure 1. However, the elimination of traditional poverty is still ongoing, and ongoing efforts are necessary to sustain these gains and prevent the emergence of new forms of poverty in the digital era. This includes ensuring equal access to the benefits of Internet development for both urban and rural residents. Despite advances in the economy and society, digital poverty remains an issue, particularly in rural areas where unequal distribution of resources and backwardness contribute to its growth [

1].

This sort of poverty is referred to as digital poverty. The difference between traditional poverty and digital poverty is that the latter separates disadvantaged information groups from the information society. The triumphs of information development cannot be utilized by individuals in order to advance themselves since these folks lack the knowledge acquisition and application abilities necessary, as shown in

Figure 2.

This suggests that rural areas continue to be the primary location of those who do not utilize the Internet. Concurrently, the Internet and other emerging media technologies play a crucial role in the provision of information, particularly in rural areas where there is little information dissemination [

2]. However, transforming people in rural China who do not now use the Internet into those who do use the Internet presents a significant challenge at this moment. In light of the information presented thus far, it should come as no surprise that the current generation of Internet technology is well received in China and that the country’s rapidly expanding population of Internet users represents an impressive demographic trend. At the same time, the advancement of technology related to new media is taking place at a breakneck speed. New media technology is playing an increasingly important part in the dissemination of information in China. The uneven economic development that has taken place across China’s various regions has led to a significant gap in the degree to which each region makes use of technology. This disparity has, in turn, contributed to the growth of the phenomenon known as digital poverty. The digital poverty that has been brought about by digital science and technology, information, knowledge and culture is simply unreachable to some people and regions in the actual social context of China. The digital spillover from the developed eastern coastal regions is unable to overcome the constraints that are caused by the physical distance between them, which results in certain regions and groups being excluded from the process of digitization. Therefore, the developed areas on the eastern coast will acquire an advantage through the polarization effect, drawing back the adjacent less developed areas, which will result in the crowding-out effect. A lack of human and material resources will prevent the less developed areas in the region from contributing their abilities and capital to the process of upgrading the region’s industrial structure. There will be no assistance for the human or material resources that are necessary for updating the region’s industrial structure, and as a result, the industrial structure of the region will be damaged to an even greater extent. This will result in an even greater disparity in the structural makeup of the various industrial sectors between the regions. The inequity in China’s rural economic development that has been created by variations in geography in the past and will be exacerbated by the emerging phenomenon of digital poverty. According to the research that has been done, digital poverty can be caused by a variety of circumstances, including the economics, geography, culture, and so on.

In order to determine the effects that digital poverty has had on China’s rural economy, it is necessary to conduct research on both the rural economy and the growth of information in the context of the shifting conditions. This study adopts the semi-structured interview method to conduct an investigation in rural areas of Shaanxi Province. Through coding the analysis of the interview texts and combining them with previous research results, it further discusses the causes and status of digital poverty of rural residents in China systematically and focuses on the relationship between the two.

2. Literature Review

The digital poverty research can be loosely divided into three phases: the initial step is The United States National Communications and Information Administration (NTLA) which initially suggested the concept of digital poverty in 1999 [

3]. In the information era, digital poverty is regarded to be the divide between those who have mastered information tools and those who have not. Due to digital poverty, the second stage of the phenomena is the expansion of researchers’ knowledge due to variations in access to information and communication technologies [

4] and communication technology application and training opportunity differences [

5]. Later, the concept of digital poverty began to produce a fundamental division, believing that digital poverty lies in the difference in knowledge, information, culture and other endowments between groups [

6]. Nowadays, digital technology is more regarded as a carrier and tool for the dissemination of knowledge information, while the ultimate result of digital poverty is personal cognition. The difference between information retrieval and learning ability is more difficult to narrow than the difference between technology access and technology training opportunities. The third stage is rejecting the digital dichotomy and digital poverty. At this stage, scholars no longer focus on digital poverty but begin to promote digital poverty. While these scholars pay attention to the fact that informatization and digitalization can promote economic development [

7], other scholars have begun to pay attention to digital poverty and call for not treating the regions already at a disadvantage of digitalization from the perspective of social differentiation, social exclusion and social inequality.

As for the research focus on digital poverty, previous works of literature generally adopt the quantitative or qualitative research methods of social sciences. Most of these studies obtained research samples from relatively backward countries and regions and focused on three areas: the manifestation dimension, influencing factors and countermeasures of digital poverty.

Many studies of digital poverty begin with its manifestation. Digital capacity, especially feasible capacity such as information acquisition, supply and application capacity, is a key indicator of digital poverty [

8]. In addition, technology acceptance is also commonly used to reveal and describe the manifestations of digital poverty, including ICT adoption motivation, ICT adoption desire and ICT acceptance degree [

9]. Among them, the motivation for ICT adoption is affected by age, gender [

10] and education level. Affordability, accessibility, availability and low ICT literacy result in insufficient ICT adoption desire [

10]. The study of the dimensions of the manifestation of digital poverty can not only help researchers clarify the categories and limits of digital poverty, but also lay a foundation for further in-depth analysis and discussion of other issues, such as the influencing factors of digital poverty and the design of digital poverty reduction policies.

Digital poverty is influenced and restricted by multiple factors, including macro structural factors, medium policy and social factors and micro individual factors. Structural factors are mainly manifested in urban and rural strata structure, economic development level and other dimensions [

11]. Policy factors are mainly reflected in the government’s investment in available infrastructure and technology, and quantitative indicators include mobile phone payment ability, computer penetration rate, Internet and broadband access ability and mobile phone penetration rate [

12]. Social factors are mainly manifested in the capital owned by digitally poor groups, such as social capital, economic capital, cultural capital, political capital and information capital [

13]. The most significant individual factor is personal or family economic income, followed by demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, educational background and related learning ability and ICT literacy [

14]. Many factors affecting digital poverty do not exist separately. The superposition and combination of macro and micro factors have caused great troubles for digital poverty groups and constrained their pace and determination to move toward the digital society.

Scholars have proposed a number of ideas for digital poverty reduction responses. According to the similarities and differences of policy design goals, objects, policies and behaviors, this study divides the digital poverty response measures in relevant works of literature into four levels: national or regional, social, community and individual.

As for solving the problem of digital poverty, from the perspective of governance subjects, the design, formulation and implementation of policies are undoubtedly the key [

15]. In addition, multiple coordination and comprehensive participation, including non-governmental organizations, cultural and public information organizations, communities and online social networks, should not be neglected [

16]. In particular, in addition to the necessary investment in infrastructure (digital technologies, platforms and equipment) and the improvement of the income and education level of the digitally poor, the development of digital poverty reduction strategies should be people-oriented, focusing on livelihood needs, digital rights, promoting digital inclusion and taking full account of demographic and geographical characteristics in policy design [

17]. Rather than generalizing, there should be targeted policy interventions for different social groups, such as women, farmers, the elderly, adolescents or school students, [

18]. In addition, at the later stage of policy implementation, it is necessary to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness and applicability of the strategy and revise the digital poverty governance plan timely and rolling manner.

3. Methodology

In this study, the semi-structured interview method was used to systematically discusses the causes and status of digital poverty of rural residents in two rural locations.

Figure 3 shows the location of the two rural areas.

Both regions are located in the Shaanxi province of China so that other potential influences on the sample data can be reduced or eliminated. Every single study sample consisted of thirty different interviews. In terms of the procedure for selecting samples, this research makes an effort to take into account the effects brought about by disparities in gender, ag, and educational level.

Figure 4 presents the interviews’ fundamental information.

The total sample included 33 females and 27 males. Occupation types mainly included farming, self-employed, full-time homemakers, grassroots village cadres, students and unemployed people.

The interview included four main questions, which are shown in

Table 1.

The interviews were conducted between January and March 2022. During the period of the research, the participants were provided with sufficient time to recall previous events and reflect on the topic at hand. This enabled the researchers to better understand the participants’ perspectives and experiences in relation to the topic. The interview lasted between 30 and 60 min for each participant, with a grand total of 110,000 words, and there were a total of 60 participants. The 60 interviewees were selected based on their residence in the rural area and their willingness to participate in the study. During the process of analyzing the data from the interviews, one-third of the texts were chosen for qualitative analysis, and the remaining two-thirds were put to use for a theoretical saturation test at a later stage. An interviewer was responsible for compiling and coding all of the interview data in order to guarantee that the data processing would be consistent. The software used for coding was NVivo 12. The answers were coded using qualitative coding techniques and were analyzed using exploratory analysis methods. In addition, the researchers adhered to all ethical standards during the whole research process to ensure that the participants would not be put in danger or suffer any harm while preparation and planning were carried out. It was made clear in advance to each person who was going to be interviewed that the information gathered from the interviews would only be utilized for academic study and not for any other purposes.

5. Strategies to Minimize Digital Poverty

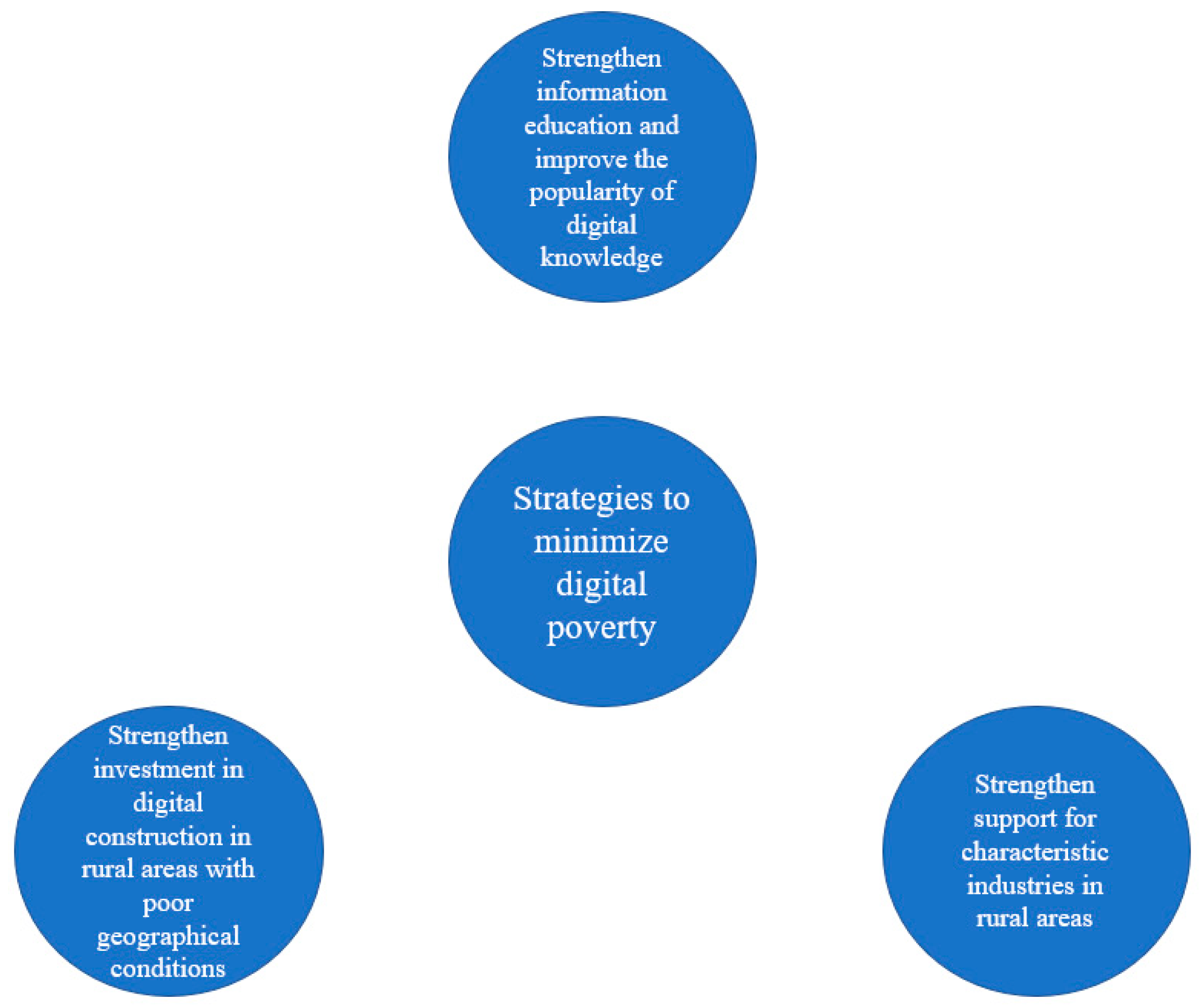

Based on the results of our research, we propose strategies to minimize digital poverty in rural locations, as shown in

Figure 7.

Strengthen information education and improve the popularity of digital knowledge. In order to lift farmers in this region out of digital poverty, improving their access to digital education is absolutely necessary [

23]. Provide adequate support for rural children’s access to digital knowledge, allocate resources in a way that is fair and equitable, build a comprehensive digital education system, continue to increase investment in schools in rural areas, collect and fully utilize the resource advantages of the entire society and allocate resources appropriately. Break the vicious cycle and direct the power of the entire society toward developing the digital knowledge learning network education and public welfare training in rural areas by readjusting network data. Increase the training of computer and network technology knowledge in the region, expand the learning channels of villagers and break the vicious circle. Utilizing the educational resources of the entire society, taking into account the technical requirements of agricultural production and operation, and directing the development of relevant agricultural education programs based on the needs of farmers are all important aspects of this process. Educational institutions are able to give online instruction in agriculturally relevant digital knowledge and technology that is acceptable to farmers. In addition, they might perform further forms of training and lobby for relevant volunteer groups and public welfare organizations to join the ranks of digital knowledge and digital training in the region.

Moreover, it is crucial for policy to take this into consideration when aiming to increase digital literacy and access among older people. A comprehensive policy approach should include the integration of technology in ways that serve their existing needs and requirements such as access to information about farming, weather updates, telehealth services and affordable means of communication with distant family members. By catering to the specific needs of older rural populations, the policy will be more effective in increasing their uptake of technology and bridging the digital divide.

Strengthen investment in digital construction in rural areas to improve network capacity [

24]. The majority of a network’s capacity is comprised of the rate of home computer ownership, the rate of home network access, and the percentage of people who utilize the network. The federal government ought to increase the amount of money it invests in the information infrastructure and digital services of rural areas. On the one hand, it has the potential to encourage broadband use a course of action and some restitution for China’s digital hamlet. It is possible to improve rural households’ network capacity and reduce the digital poverty caused by recent advances in technology by targeting rural households in locations that present logistical challenges. In the meantime, policies that are favorable to digital service providers have been put into place. Provide low-threshold preferred pricing for telecommunications services, exclusive broadband information services, increased support and services, and address the issue of a defective digital infrastructure for people who are less fortunate are some examples. Ensure that low-income individuals have access to high-quality and universal telecommunications services; improve the construction of rural network capacity in these regions; and raise the percentage of people who use the Internet and have fixed broadband connections as a proportion of all Internet users.

Strengthen support for characteristic industries in rural areas to promote high-quality economic development. Rural economic vitality is a prerequisite for eliminating digital poverty among farmers. Investment in the local economy cannot be divorced from the creation of information infrastructure or the strengthening of digital popularization. On the basis of the law of market development, mature enterprises are required to actively drive other enterprises, make good cooperative relationships, increase enterprise innovation consciousness and unite with other enterprises to create a new production model. Extend the production chain, construct a new industrial system, further optimize the industrial structure, establish a distinctive industrial brand, boost farmers’ income and alleviate digital poverty among rural farmers.

6. Conclusions

First, this study analyzes the current digital poverty of rural residents, discusses the digital material poverty and digital literacy of rural residents, and discusses the two core causes of digital poverty in the process of rural residents’ integration into the digital society, namely the basic state of insufficient digital efforts and lack of digital support. Finally, from the perspectives of research, elements, disciplines, theories and methods, this paper discusses the theoretical value of digital experience, a new research variable, in the research of digital poverty. Based on the theory of information ecology and the general idea of the construction of a public cultural service system, this paper puts forward several countermeasures to implement the digital poverty reduction action of rural residents from three aspects: information itself (digital content), information subject (rural residents) and information environment (digital facilities).

The limitation of this study lies in the regional representation and quantity limitation of in-depth interview samples; the universality of relevant conclusions still needs to be tested further. In future studies, on the one hand, the sampling range can be expanded to discuss the potential relationship comprehensively and deeply between the causes and the state of digital poverty of rural residents. On the other hand, based on the larger number of patterns, the moderating effects of different types of digital poverty groups on the relationship between causes and states are discussed.