Understanding Social Media Users’ Mukbang Content Watching: Integrating TAM and ECM

Abstract

1. Introduction

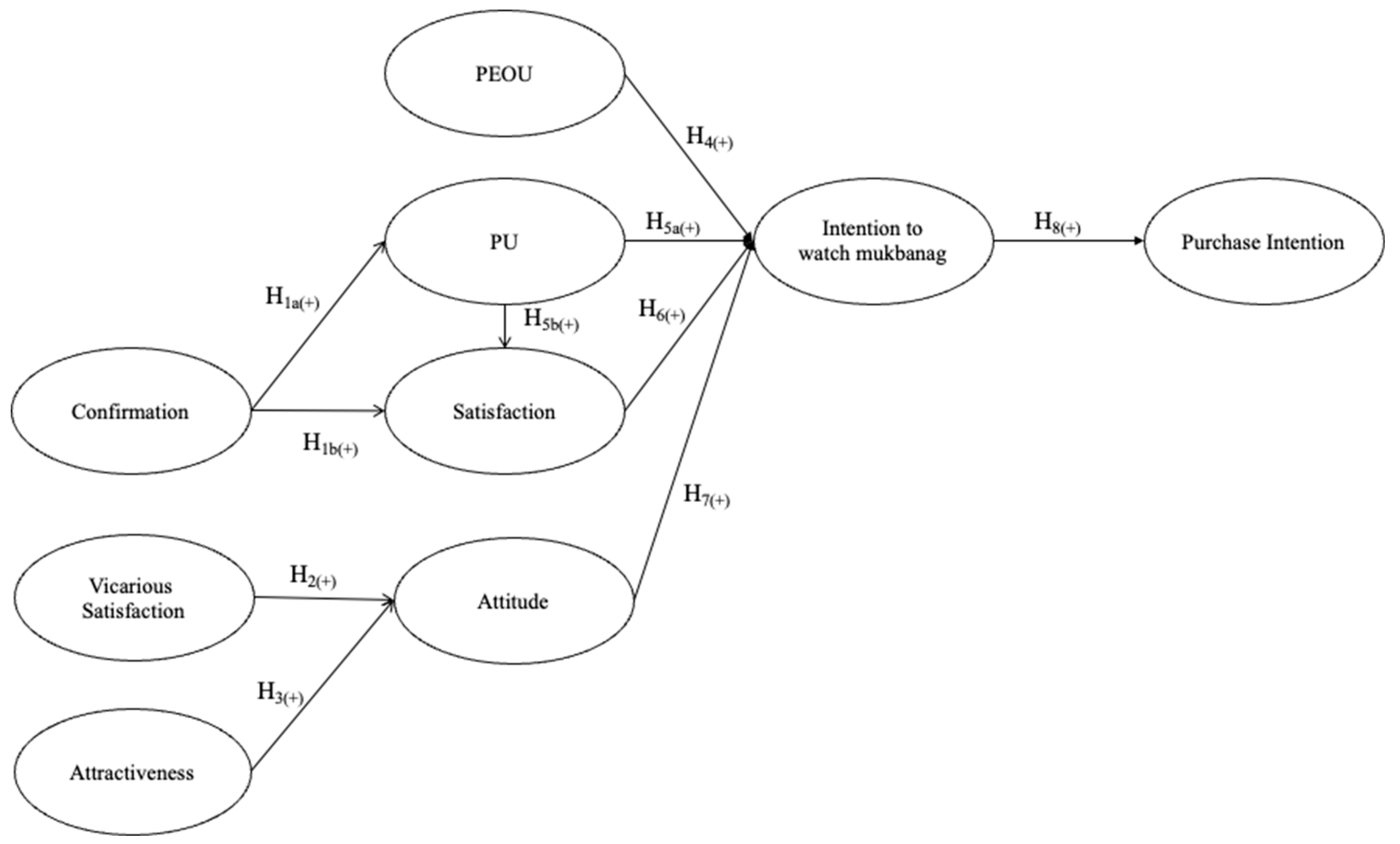

- What is the effect of the intention of watching mukbang content on the purchase intention of the food items in mukbang?

- How do factors of technology adoptions and confirmation affect the intention to watch mukbang and purchase intentions?

- What is the impact of vicarious satisfaction and attractiveness on attitudes toward mukbang content?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media Content

2.2. Technology Acceptance Model

2.3. Expectation–Confirmation Model

3. Research Design

3.1. Confirmation

3.2. Vicarious Satisfaction

3.3. Attractiveness

3.4. Perceived Ease of Use

3.5. Perceived Usefulness

3.6. Satisfaction

3.7. Attitude

3.8. Intention to Watch

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Measurement Instrument

4.2. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model

5.2. Structural Model

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Scales | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmation | CON1 | My experience with watching this video was better than I had expected. | [68] |

| CON2 | The product and service provided by this video were better than I expected them to be. | ||

| CON3 | Overall, most of my expectations of using this video were confirmed. | ||

| Attractiveness | ATR1 | I find the mukbang YouTuber attractive. | [69] |

| ATR2 | I think the mukbang YouTuber is quite enticing. | ||

| ATR3 | The mukbang YouTuber is charming. | ||

| Vicarious Satisfaction | VCS1 | While watching mukbang, I feel assimilated with the characters. | [62] |

| VCS2 | While watching mukbang, I can forget my daily life. | ||

| VCS3 | While watching mukbang, I feel like I am eating. | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEU1 | Mukbang content is clear and understandable. | [70] |

| PEU2 | Watching mukbang does not require a lot of mental effort. | ||

| PEU3 | I find watching mukbang easy. | ||

| Perceived Usefulness | PUS1 | I can decide more quickly and more easily which food I want to go and eat than I could before I started watching mukbang. | [70] |

| PUS2 | I can better decide which food I want to go and eat than I could before I started watching mukbang. | ||

| PUS3 | I am better informed about new food when I watch mukbang. | ||

| Satisfaction | SAT1 | I am satisfied with my decision to watch the video. | [26] |

| SAT2 | My choice to watch the video was a wise one. | ||

| SAT3 | Overall, I am satisfied with the experience of watching the video. | ||

| Attitude | ATT1 | I feel good watching mukbang content. | [26] |

| ATT2 | I like watching mukbang content on YouTube. | ||

| ATT3 | It is wise to watch mukbang content on YouTube. | ||

| Intention to Watch | ITW1 | The probability of me considering watching mukbang is high. | [21] |

| ITW2 | If I were looking for something to watch, the likelihood I would watch mukbang is high. | ||

| ITW3 | My willingness to watch mukbang is high. | ||

| Purchase intention | ITP1 | If I were to buy an F&B product, I would consider buying what I saw in the video. | [71] |

| ITP2 | The likelihood of my purchasing an F&B product that I saw in the video is high. | ||

| ITP3 | My willingness to buy an F&B product that I saw in the video is high. |

References

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.H.; Han, J.S. The Effect of Video User Created Content Tourism Information Quality on User’s Satisfaction, Visit Intention and Information Sharing Intention. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 27, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Thal, K. The Impact of Social Media on the Consumer Decision Process: Implications for Tourism Marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.; Daly, T. Customer Engagement with Tourism Social Media Brands. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Kim, C. A Study on the Effectiveness of Video Advertisements Generated by Social Media Users: Centered on Video Content Type and Information Framework. J. Korea Multimed. Soc. 2022, 25, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, C.G.; Deng, D.S.; Chi, O.H.; Lin, H. Framing Food Tourism Videos: What Drives Viewers’ Attitudes and Behaviors? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022. Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Haynes, P.; Archila-Godínez, J.C.; Nguyen, M.; Xu, W.; Feng, Y. Exploring Food Safety Messages in an Era of COVID-19: Analysis of YouTube Video Content. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J.R. Impact of Social Media Marketing Features on Consumer’s Purchase Decision in the Fast-Food Industry: Brand Trust as a Mediator. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babenskaite, G.; Yang, M. Mukbang Influencers: Online Eating Becomes a New Marketing Strategy: A Case Study of Small Sized Firms in China’s Food Industry. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, S.F.S.; Das, M. Content Analysis Of Mukbang Videos: Preferences, Attitudes And Concerns. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 4811–4822. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.-H.; Jo, G.-B. A Study on the Influence of Content Properties of YouTube Mukbang on Brand Selection: Focusing on Chicken Franchise Brand. J. Korea Soc. Comput. Inf. 2021, 26, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Cho, C.-H. A Study on Use Motivation, Consumers’ Characteristics, and Viewing Satisfaction of Need Fulfillment Video Contents (Vlog/ASMR/Muk-Bang). J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2020, 20, 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, H. Eating Together Multimodally: Collaborative Eating in Mukbang, a Korean Livestream of Eating. Lang. Soc. 2019, 48, 171–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding Information Systems Continuance: An Expectation-Confirmation Model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.; Chen, C. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Study of Lifestyles, Contextual Factors, Mobile Viewing Habits, TV Content Interest, and Intention to Adopt Mobile TV. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Mahmood, K.; Islam, T. Understanding the Facebook Users’ Behavior towards COVID-19 Information Sharing by Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and Gratifications. Inf. Dev. 2021. Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S. Mukbang Is Changing Digital Communications. Anthropol. News 2018, 59, e90–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. A Study on the Influence of the Internet Personal Broadcasting ‘Mukbang’ Viewing on Real Life. Master’s Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.S. A Study on the Effect of View Motives on the View Satisfaction and Behavior Intentions of One-Person Media Food Contents: Focused on ‘Mokbang’and ‘Cookbang’. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2019, 25, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Ko, E.; Kim, J. SNS Users’ Para-Social Relationships with Celebrities: Social Media Effects on Purchase Intentions. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2015, 25, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R.B.; McHugh, M.P. Development of Parasocial Interaction Relationships. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 1987, 31, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.; Sung, B.; Lee, S. I like Watching Other People Eat: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of the Antecedents of Attitudes towards Mukbang. Australas. Mark. J. (AMJ) 2019, 27, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjani, L.; Mok, T.; Tang, A.; Oehlberg, L.; Goh, W.B. Why Do People Watch Others Eat Food? An Empirical Study on the Motivations and Practices of Mukbang Viewers. In CHI’2020, Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kircaburun, K.; Harris, A.; Calado, F.; Griffiths, M.D. The Psychology of Mukbang Watching: A Scoping Review of the Academic and Non-Academic Literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 1190–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styawan, Z.; Buwana, D.S. Watching Attitude Factors in Delivering Mukbang Shows. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Bus. (JHSSB) 2023, 2, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Yurdagül, C.; Kuss, D.; Emirtekin, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Problematic Mukbang Watching and Its Relationship to Disordered Eating and Internet Addiction: A Pilot Study among Emerging Adult Mukbang Watchers. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; Arachchilage, N.A.G.; Abbasi, M.S. A Critical Review of Theories and Models of Technology Adoption and Acceptance in Information System Research. Int. J. Technol. Diffus. (IJTD) 2015, 6, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Yahaya, N.; Alalwan, N.; Kamin, Y.B. Digital Communication: Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Usage for Education Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-Y.; Juan, P.-J.; Lin, S.-W. A Tam Framework to Evaluate the Effect of Smartphone Application on Tourism Information Search Behavior of Foreign Independent Travelers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J. Effects of the Characteristics of TV and Internet Food-Related Programs on Dietary Self-Efficacy of Regular Viewers-Focused on Single Household. J. Converg. Cult. Technol. 2019, 5, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Gweon, O.-C. An Integrated Model for the YouTube ’Mukbang’ Content Use Motivation and Continuous Use Intention: Focusing on Uses and Gratifications Approach and Technology Acceptance Model. J. Digit. Converg. 2021, 19, 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A. An Empirical Analysis of the Antecedents of Electronic Commerce Service Continuance. Decis. Support Syst. 2001, 32, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Berry, L.L. Delivering Quality Service: Balancing Customer Perceptions and Expectations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 0029357012. [Google Scholar]

- Thong, J.Y.L.; Hong, S.-J.; Tam, K.Y. The Effects of Post-Adoption Beliefs on the Expectation-Confirmation Model for Information Technology Continuance. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Liu, M.-L.; Lin, C.-P. Integrating Technology Readiness into the Expectation–Confirmation Model: An Empirical Study of Mobile Services. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankton, N.K.; McKnight, H.D. Examining Two Expectation Disconfirmation Theory Models: Assimilation and Asymmetry Effects. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kang, M.; Jo, H. Determinants of Postadoption Behaviors of Mobile Communications Applications: A Dual-Model Perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2014, 30, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Cho, H.; Chi, C.G. Consumers’ Continuance Intention to Use Fitness and Health Apps: An Integration of the Expectation–Confirmation Model and Investment Model. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 34, 978–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Lin, J.C.-C. What Drives Purchase Intention for Paid Mobile Apps?—An Expectation Confirmation Model with Perceived Value. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, P. #I Envy, Therefore, I Buy!#: The Role of Celebgram Trustworthiness and Para-Social Interactions in Consumer Purchase Intention. J. Manaj. Kewirausahaan 2021, 23, 186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, K.; Perez, C. You Follow Fitness Influencers on YouTube. But Do You Actually Exercise? How Parasocial Relationships, and Watching Fitness Influencers, Relate to Intentions to Exercise. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Choi, M.; Han, I. User Behaviors toward Mobile Data Services: The Role of Perceived Fee and Prior Experience. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 8528–8536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniar, R.; Rawski, G.; Yang, J.; Johnson, B. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Social Media Usage: An Empirical Study on Facebook. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2014, 27, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, C.; Oliveira, T. Understanding the Impact of M-Banking on Individual Performance: DeLone & McLean and TTF Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fraihat, D.; Joy, M.; Sinclair, J. Evaluating E-Learning Systems Success: An Empirical Study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.Y.; Shankar, V.; Erramilli, M.K.; Murthy, B. Customer Value, Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Switching Costs: An Illustration from a Business-to-Business Service Context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phonthanukitithaworn, C.; Sellitto, C. Facebook as a Second Screen: An Influence on Sport Consumer Satisfaction and Behavioral Intention. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Agag, G.; El-Masry, A.A. Understanding Consumer Intention to Participate in Online Travel Community and Effects on Consumer Intention to Purchase Travel Online and WOM: An Integration of Innovation Diffusion Theory and TAM with Trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H. Determinants of Continuance Intention towards E-Learning during COVID-19: An Extended Expectation-Confirmation Model. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-Q.; Chen, H.-G. Social Media and Human Need Satisfaction: Implications for Social Media Marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korgaonkar, P.K.; Wolin, L.D. A Multivariate Analysis of Web Usage. J. Advert. Res. 1999, 39, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.-P.; Shavitt, S. Persuasion and Culture: Advertising Appeals in Individualistic and Collectivistic Societies. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 30, 326–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallud, J.; Straub, D.W. Effective Website Design for Experience-Influenced Environments: The Case of High Culture Museums. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najar, A.H.; Hamid Rather, A. Mediating Role of Guest’s Attitude toward the Impact of UGC Benefits on Purchase Intention of Restaurants; Extending Social Action and Control Theories. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2021, 24, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An Assessment of the Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing Research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing Construct Validity in Organizational Research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-K.; Kim, K.-O. Relationship between Viewing Motivation, Presence, Viewing Satisfaction, and Attitude toward Tourism Destinations Based on TV Travel Reality Variety Programs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, M.Y.; Zhang, G.Y.; Chen, H. Adoption of Social Media Search Systems: An IS Success Model Perspective. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2018, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veland, R.; Amir, D.; Samije, S.-D. Social Media Channels: The Factors That Influence the Behavioural Intention of Customers. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2014, 12, 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.; Shim, S.W.; Jin, H.S.; Khang, H. Factors Affecting Attitudes and Behavioural Intention towards Social Networking Advertising: A Case of Facebook Users in South Korea. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, H.F. Factors Affecting Purchase Intention in YouTube Videos. J. Knowl. Econ. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 11, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. Modern Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2014; ISBN 1315700891. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.E.; Watkins, B. YouTube Vloggers’ Influence on Consumer Luxury Brand Perceptions and Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5753–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, H. User Acceptance of Hedonic Information Systems. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Independent Variable/Affecting Factor | Dependent Variable | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | Host attractiveness, Mediated voyeurism, Novelty perception, Loneliness, Health consciousness, Collectivism, Social normative influence, Attitude | Intention to watch mukbang | Asians are likely to watch mukbang because of host attractiveness and social normative influence. On the other hand, Caucasians watch mukbang because of host attractiveness, perceived novelty, and social normative influence. |

| [23] | Socialization, Information, Hunger, Entertainment | Watching mukbang | Mukbang demonstrates a wide range of users’ motivations such as socialization, information, hunger, and entertainment. |

| [24] | Social use, Sexual use, Entertainment Use, Eating use, Escapist use | Mukbang watching | Viewers watch mukbang for social, sexual, entertainment, eating, and/or as an escapist reason. |

| [25] | Attractiveness, Mediation voyeurism, New perception, Solitude, Health awareness, Collectivity, Social normative influence, Watching attitude | Viewing intentions | Attractiveness, mediation voyeurism, new perception, solitude, health awareness, and social normative influence had impact on the watching attitude. |

| [26] | Problematic mukbang watching | Eating disorders, Internet addiction | Problematic mukbang watching had impact on disordered eating and internet addiction. |

| Construct | Items | Mean | St. Dev. | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α (1) | C.R (2) | AVE (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmation | CON1 | 2.050 | 1.109 | 0.922 | 0.911 | 0.944 | 0.848 |

| CON2 | 2.075 | 1.119 | 0.927 | ||||

| CON3 | 1.997 | 1.077 | 0.914 | ||||

| Attractiveness | ATR1 | 1.857 | 1.082 | 0.889 | 0.815 | 0.890 | 0.729 |

| ATR2 | 1.774 | 0.892 | 0.822 | ||||

| ATR3 | 1.990 | 1.262 | 0.849 | ||||

| Vicarious Satisfaction | VCS1 | 2.148 | 1.441 | 0.948 | 0.926 | 0.953 | 0.871 |

| VCS2 | 2.058 | 1.350 | 0.934 | ||||

| VCS3 | 2.153 | 1.517 | 0.918 | ||||

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEU1 | 2.586 | 1.653 | 0.947 | 0.934 | 0.958 | 0.883 |

| PEU2 | 2.586 | 1.592 | 0.948 | ||||

| PEU3 | 2.689 | 1.688 | 0.924 | ||||

| Perceived Usefulness | PUS1 | 3.201 | 1.238 | 0.916 | 0.931 | 0.956 | 0.880 |

| PUS2 | 3.283 | 1.242 | 0.953 | ||||

| PUS3 | 3.281 | 1.298 | 0.944 | ||||

| Satisfaction | SAT1 | 3.143 | 1.132 | 0.927 | 0.839 | 0.903 | 0.759 |

| SAT2 | 3.208 | 1.167 | 0.938 | ||||

| SAT3 | 3.055 | 1.219 | 0.734 | ||||

| Attitude | ATT1 | 1.782 | 1.031 | 0.883 | 0.894 | 0.934 | 0.826 |

| ATT2 | 1.915 | 1.134 | 0.923 | ||||

| ATT3 | 1.845 | 1.060 | 0.919 | ||||

| Intention to Watch | ITW1 | 2.110 | 1.383 | 0.930 | 0.926 | 0.953 | 0.872 |

| ITW2 | 2.138 | 1.403 | 0.935 | ||||

| ITW3 | 2.158 | 1.419 | 0.936 | ||||

| Intention to Purchase | ITP1 | 2.268 | 1.500 | 0.928 | 0.894 | 0.934 | 0.824 |

| ITP2 | 2.008 | 1.264 | 0.884 | ||||

| ITP3 | 2.100 | 1.404 | 0.911 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirmation | 0.921 | ||||||||

| 2. Attractiveness | 0.737 | 0.854 | |||||||

| 3. Vicarious Satisfaction | 0.723 | 0.719 | 0.933 | ||||||

| 4. Perceived Ease of Use | 0.251 | 0.307 | 0.301 | 0.940 | |||||

| 5. Perceived Usefulness | −0.091 | −0.093 | −0.088 | −0.074 | 0.938 | ||||

| 6. Satisfaction | −0.016 | −0.020 | −0.037 | −0.030 | 0.327 | 0.871 | |||

| 7. Attitude | 0.761 | 0.773 | 0.725 | 0.341 | −0.124 | −0.062 | 0.909 | ||

| 8. Intention to Watch | 0.696 | 0.687 | 0.722 | 0.371 | −0.115 | −0.071 | 0.768 | 0.934 | |

| 9. Intention to Purchase | 0.604 | 0.608 | 0.631 | 0.478 | −0.158 | −0.067 | 0.726 | 0.703 | 0.908 |

| H | Cause | Effect | Coefficient | T-Value | Hypothesis |

| H1a | Confirmation | Perceived Usefulness | −0.091 | 2.129 | Not Supported |

| H1b | Confirmation | Satisfaction | 0.014 | 0.253 | Not Supported |

| H2 | Attractiveness | Attitude | 0.520 | 7.952 | Supported |

| H3 | Vicarious Satisfaction | Attitude | 0.351 | 5.202 | Supported |

| H4 | Perceived Ease of Use | Intention to Watch | 0.123 | 3.160 | Supported |

| H5a | Perceived Usefulness | Satisfaction | 0.328 | 7.468 | Supported |

| H5b | Perceived Usefulness | Intention to Watch | −0.010 | 0.284 | Not Supported |

| H6 | Satisfaction | Intention to Watch | −0.019 | 0.526 | Not Supported |

| H7 | Attitude | Intention to Watch | 0.724 | 19.192 | Supported |

| H8 | Intention to Watch | Intention to Purchase | 0.703 | 16.320 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, H.G. Understanding Social Media Users’ Mukbang Content Watching: Integrating TAM and ECM. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054013

Song HG. Understanding Social Media Users’ Mukbang Content Watching: Integrating TAM and ECM. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054013

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Hyo Geun. 2023. "Understanding Social Media Users’ Mukbang Content Watching: Integrating TAM and ECM" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054013

APA StyleSong, H. G. (2023). Understanding Social Media Users’ Mukbang Content Watching: Integrating TAM and ECM. Sustainability, 15(5), 4013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054013