Abstract

Heritage trails are an effective way to preserve cultural sustainability. Nowadays, heritage trails have been widely developed as tourism products either domestically or abroad. Megalithic stones are an ancient tradition of high value that has interesting functions and backgrounds. Moderni-zation with infrastutural development, and changes in religion in society have caused the mega-lithic stone tradition to be less practiced and increasingly declining. One of the effective ways to preserve megalithic stones from further decline is by building heritage trails as a tourism product. Many megalithic stones are located in sloping areas. In this study, least-cost path analysis (LCPA) in GIS applications was used to identify cost-effective and sloping routes to produce heritage trails. Study data were obtained from fieldwork in Tambunan. The benefits of this study provide ex-posure to the outside world about the megalithic stone tradition, and determine the appropriate routes to develop heritage trails in the District, and assist in the economy of the local population.

1. Introduction

Regarding sustainable development, cultural sustainability entails preserving cultural traditions, heritage preservation, culture as a distinct entity, and the question of whether any particular cultures will continue to exist in the future [1]. Culture is both an enabler and driver of the economic, social, and environmental components of sustainable development, from cultural legacy to cultural and creative enterprises [2]. Thus, in terms of spatial planning, cultural heritage should be given special protection as to preserving not only the object or structure but also its background [3]. This should be done for all forms of cultural heritage even though they are not included in the UNESCO World Heritage list [4].

One of the ways to achieve cultural sustainability is through tourism. Tourism can provide a source of growth opportunities for enterprise development and job creation and it can stimulate investment and support for local services, even in relatively remote communities, bringing significant economic value to natural and cultural resources. This can result in direct income from visitor spending for their conservation and an increase in support for conservation from local communities and be a force for understanding and peace between cultures [1]. Navrud and Ready [5] and Salazar and Marques [6] evaluated the worth of monuments by converting them regarding potential for profit from tourism or by using techniques for determining replacement value.

In Malaysia, the tourism sector contributes to rural and urban development, especially in generating the economy of the local population [7]. Although there are various tourism products, such as homestays, beaches, and food, in Malaysia, there are still many rural areas that have not been explored [8]. One of the unexplored tourist products is the megalithic stones of Tambunan District, in Sabah, Malaysia’s northernmost state on Borneo Island. Erecting megalithic stones was the practice of using of large stones by ancient people for purposes such as marking migratory routes, tombstones, oath stones, boundary markers, peace-making memorials, protective stones, and so on. Nowadays, the megalithic stone, a tradition of the Kadazan Dusun community in Sabah (also known as Dusun or Kadazandusun) is declining. Many megaliths have been broken, knocked down, or moved due to development projects ostensibly to benefit the local population [9]. A megalithic stones that have a unique backgrounds and are part of the natural environment have the potential to be developed as a tourism product that is the heritage trail of the megaliths stone to attract tourists.

Additionally, such measures also help in preserving megalithic stones from destruction and subsequently preserve the cultural sustainability. However, the locations of some of those megalithic stones in sloping areas makes it difficult to open these areas due to safety risks, accessibility, and higher expenditure costs compared to megaliths in non-sloping areas.

Therefore, these obstacles can be reduced by identifying the least-cost route. This least-cost route can result in routes that saves time, save costs, and have low-security risks. This is suitable for tourists that are only capable of certain leveld of route difficulty because of health and age. Tourism activities based on age categories are important in the field of tourism to attract more tourists. This is supported by Homburg and Giering [10], in which age can influence the strength of the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty of visitors to tourism activities. Therefore, the appropriate age category for a tourism activity must be considered.

GIS is a tool that is often used to identify and determine the cultural patterns of an area. The ability of GIS in producing ethnographic density level mapping shows that this tool can also solve the above problem by producing the least-cost route [11]. The GIS-based spatial analysis for developing the route is least cost path analysis (LCPA). This analysis can show the best route from one point to another on the cost surface or raster [12]. This LCPA analysis is very effective in studies such as this and very interesting to explore.

LCPA is widely used in studies in the fields of health, environment, development, archeology, history, and engineering. Brabyn and Barnett [13] used this analysis in the field of health to examine the extent to which areas in New Zealand have access to universal positioning (GP). The study of Bagli et al. [14] used LCPA analysis in the field of health to channel power lines to reduce their impact on human health, landscape, and ecosystem. Meanwhile, Chandio et al. [15] used LCPA to identify road routes according to sloping terrain [15]. In 2014, Rogers et al. [16] used LCPA analysis in archaeological studies to assist archaeologists in upland areas. However, LCPA analysis has not yet been conducted in tourism field studies. Therefore, in this study, LCPA analysis is used for mapping megalithic stone heritage trails on sloping areas as a tourism product.

2. Megalithic Stones in Southeast Asia

The countries in Southeast Asia where megalithic stones can be found stated in previous studies, are Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Indonesia and also Sabah, and Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo. In Thailand, the sites found to have megalithic stones are Ta Van Giay, Mau Son, Chop Chai, Nam Dan (Xin Man, Ha Giang) and dan Soc Son (Ha Noi). The types of megalithic stones found are stone cubes, stone spheres, menhirs, and dolmens. These megalithic stones were erected to mark the boundaries of temples, graves, memorials, and the spirits of village or house guardians [17].

In Vietnam, megalithic stone sites are Ta Van Giay, Mau Son, Chop Chai, Nam Dan (Xin Man, Ha Giang), and Soc Son (Ha Noi). The types of megalithic stones found in Vietnam include large stone formations and dolmens. Usage of megalithic stones in Vietnam is for ritual and burial ceremonies and graves [18]. There are also two sites found with megalithic stones, namely Xieng Khouang and Luang Prabang Provinces, in the northern part of Laos. The type of megalithic stone found in Laos is the stone jar. There are 97 areas consisting of stone jars made of sandstone, breccia, limestone, conglomerate, and granite. This stone jar is located on hills or mountains [19]. However, the function of these stone jars has not been identified yet [19,20].

In Indonesia, the areas that are found to have megalithic stones can be divided into West Java, East Java, West Flores, Central Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, West Sumatra, North Sumatra, West Kintamani in Bali, and East–West. The types of megalithic stones found in Indonesia are graves, stone chambers, dolmens, stone pools, terraced buildings and stepped pyramids, coffins and sarcophagi, Kenong stones (that merely resemble kenong but are not lithophones), Dakom stones (pit marker stones), Temu Bangle stones, stone enclosures, stone statues, stone altars, menhirs, monoliths, Kelamba, stone barrels, and so on. The function of these megalithic stones is tombs and places for dishes for worship, places to place food for worship, graves, memorials, symbols of strength, and ancestral dwellings [21,22].

In Malaysia, the states found to have megalithic stones are Negeri Sembilan, Melaka, Sarawak, and Sabah. Megalithic stones that can be found in Malaysia are menhirs, carved stones, dolmens, large stone piles, cemeteries, burial sites occasionally with Chinese pottery burials, stone pit burials, and others. The functions of megalithic stones in Malaysia are as boundary markers, memorial stones, protective stones, and so on [23,24,25,26,27].

3. Megalithic Stone Heritage Trails as a Tourism Product

A trail is a route that has its special features and a specific theme [11]. Heritage trails are developed with diverse themes to produce routes that connect sites, attractions, and other tourism businesses. Information and stories related to the heritage trail theme are exhibited for tourists’ gaze along the trail [28,29]. Each heritage trail is different in distance, whether far or near, locations and scopes, e.g., short walks in the city center or long climbs, driving to enjoy the beauty along the route, or through international trade routes [30].

A Megalithic stone refers to either a large menhir, or a naturally occuring monolith [31]. In ancient times, people used megalithic stones for various purposes, such as commemorating historical events, deceased warriors, marking area boundaries, marking grave areas, and so on. According to Soedewo et al. [22] and Koentjaranigrat [32], people formerly believed that there was a spirit that inhabited a large stone or large tree. Therefore, ancient society sometimes erected large stones and to indicate agreements between the human and spiritual realms for the protection of villages from all forms of harm.

This practice has been a community tradition for a long time. In Tambunan, megaliths were erected for the following purposes: to mark the ancient routes taken over eons by waves of Dusunic peoples from Nunuk Ragang (an ancient village located in to-day’s Ranau District to the east, that was the origin of many Dusunic ethnic groups in Sabah) across the mountain ranges onto the Tambunan plain; as oathstones; to com-memorate peace-making between formerly warring villages; to commemorate the end of epidemics such as smallpox; as markers for tamu (market) grounds where warring parties had to lay down their arms to trade; as ancient grave markers in village graveyards; as boundary markers on bunds in wet padi fields to distinguish fields inherited by different families; to commemorate famous people in oral history; to commemorate the coming of Christianity; as memorials for people who died and were buried away from their village. Some old megaliths were believed to be inhabited by guardian spirits that were thought to protect nearby villages from attacks by other malevolent spirits causing epidemics.

Today, a broken line of megaliths marking the ancient route from Nunuk Ragang can still be seen. Peace-making memorial stones and others can still be found. Although grave styles have changed, megaliths are still occasionally erected in village graveyards for those who have died and been buried far from home. Old boundary markers in padi fields are still found. Some churches have old commorative megaliths in front. This megalithic stone tradition of the indigenous Kadazan Dusun has gradually declined in recent years possibly partly due to changes in beliefs among the community over the past century. More recent destructive activities by outsiders such as agencies involved in infrastructure development, however, have played a major part in this decline. This has caused the megalithic stone tradition to be damaged due to the lack of awareness of this cultural heritage. One of the effective ways to promote conservation and preservation of this cultural heritage is by developing heritage trails with a megalithic stone theme [29].

According to Jaafar et al. [33], a heritage trail is a tourism product that is commonly used in promoting heritage sites [34]. Visitors can observe for themselves the nature and cultural heritage found along the trail [35]. Furthermore, heritage and cultural tourism are growing nowadays [36]. Therefore, the legacy of megalithic stones can be used in promoting economic development [37]. Through the introduction of megalithic stone heritage trails as a tourism product, tourists have the opportunity to visit the countryside, get to know the lifestyle and culture of the local people, or get to know the agricultural activities carried out. Indirectly, a heritage trail will provide opportunities for the local community to generate income.

A tourist destination must meet the five elements of tourism, namely attractions, activities, accessibility, accommodation, and facilities [38]. Attractions refer to interesting or unique places that can attract tourists, such as beaches or places to eat. Activities refer to activities that can be carried out at a tourist site, such as trekking, rafting, rowing activities, cultural program arrangements, and so on. Accessibility refers to facilities that allow tourists to reach the tourist destination quickly, safely, and easily [38], for example, provision of transportation from hotels to tourist destinations. This also includes nearby roads of the area. Accommodation refers to places where tourists spend the night, whether hotels, homestays, resorts, and so on. [39]. Finally, facilities refers to all facilities that facilitate tourists, such as toilets, electricity, water supply, hospitals, banks, and so on. [12]. Thus, the megalithic stone heritage trails to be produced as a tourism product must meet these five elements.

Therefore, mapping the heritage trails considering these five elements of is very important as a guide to tourism. Tourism mapping is very suitable to be completed using GIS. This is because GIS can identify the tourism elements involved and at the same time determine the level of difficulty of the existing heritage trails [40,41].

4. Research Area

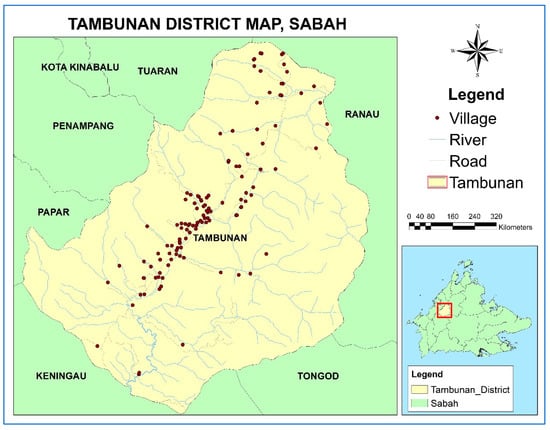

The mapping of this megalithic stone heritage trail was carried out in Tambunan, Sabah. Tambunan is an administrative District of around 1347 square kilometres, located in the interior division of Sabah. It is admnister-erd through the District Office in the small township, also called Tambunan, in the centre of the District. The distance between Kota Kinabalu and Tambunan town is 75 kilometres apart. Tambunan District is an upland plain lying at a lower altitude of around 636 me-tres (2087 feet), traversed by the Pagalan River, and surrounded the Crocker and Trusadi Ranges. a town where It has over 100 villages, of which 88 are major villages registered with the District Office. The main ethnic group is the indigenous Kadazan Dusun at over 86% of the population of the District [40].

Rice is their staple crop. It is cultivated for family consumption and, according to custom, it cannot be sold. Traditional rice varieties are grown in wet padi fields (devolvable usu-fruct) on the plain, and in dry hillside padi plots (circulating ususfruct). Commerial crops include ginger (Tambunan is a major ginger producer in Malaysia), various fruits, vegeta-bles and other products. Due to its higher altitude, Tambunan has a mild tropical climate all year round and is known for its beautiful and pristine natural attractions that suitable for tourism.

Tambunan was chosen for this study, because this was suggested by the indigenous Kadazan Dusun community leaders during initial meetings for a previous project on cul-tural mapping in Tambunan. It was noted that Tambunan District had many megaliths that had been erected in ancient times to mark the route walked from Nunuk Ragang down the plain from Kampung Widu in the northeast to beyond Kampung Tobilung in the southwest. Village locations were plotted in that project, and other cultural data in-cluding any associated megaliths was collected, but further research on the stones them-selves and their precise locations was neededThus, Tambunan was chosen to conduct the precise onsite coordinates and physical measurements of the megaliths and to propose the development of megalithic stone her-itage trails for heritage-based tourism. The location of the study area is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

5. Data

The data used in this study are data from fieldwork conducted in Tambunan for the Geographic Information System (GIS) integration with the megalithic traditions in cultur-al heritage and tourism management in the Tambunan District (refer to Table 1). Before the fieldwork was carried out, a meeting with the Mr. Sobitun Makajil, the Tambunan District Officer together with other senior staff, representatives of the Tambunan Native Court, and Miss Patricia Philip Kitingan, President of the Tambunan Tourism Association and oth-ers, was held in the meeting room of the Tambunan District Office. This meeting was conducted to introduce the project to community leaders in Tambunan and obtain their permission to carry it out and to visit the actual locations of megalithic stones found in Tambunan. After this, a series of visits to the megalithic stone sites were conducted. The actual locations of the megaliths were recorded using a GPS device. In addition, un-structured interviews were also conducted to find out the background of each mega-lithic stone, its function, and the local name of the megalith. The information was filtered through three processes, namely verification and measurement, data cleaning, and data format conversion. A GIS database consisting of spatial and attribute data was developed from this data. The government Tambunan Map has been used as a basic map to produce the boundaries of the Tambunan District, villages, roads, rivers, the location of megalithic stones, and the location of tourist elements, while attribute data was used for reference to spatial data. In addition, Google maps were also used to identify locations for tourism elements. Since Tambunan is a rural area, the price for most of the tourism elements are reasonable. As an example, the current price for accommodation in this area can be as low as RM40 (USD9) only. Therefore, potential tourists have no need to worry about which tourism elements to choose from as they are quite affordable.

Table 1.

Data of the study.

6. Methodology

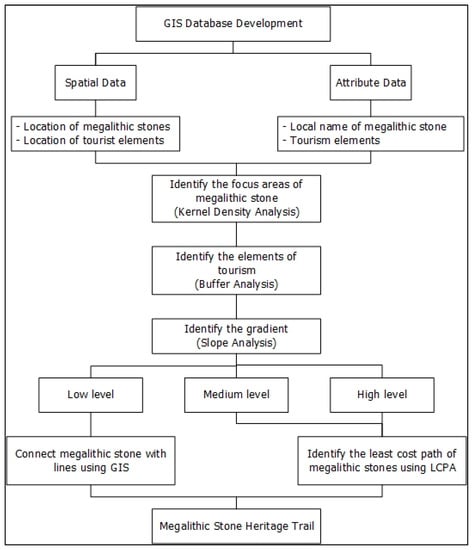

The data obtained from the fieldwork were included in a GIS application for the de-velopment of a spatial database and attribute data. The coordinate system used in this study was “Timbalai_1948_RSO_Borneo_Meters”. The spatial data contained the loca-tions of megalithic stones and the location of tourism elements, while the attribute data contained local names of megaliths and tourism elements involved in this study. Then, kernel density analysis was used to identify areas of focus for megalithic stones. This was followed by the process of identifying tourism elements that are close to each megalithic stone which was a distance of 500 m from the megalithic stones by using buffering analysis. Next, slope analysis was used to identify the gradient of megalithic stone loca-tions. Once the gradient was identified, the concentrated megalithic stones were divided into low, medium, and high levels based on the gradients. For megalithic stones located in low-sloping areas, heritage trails were created by connecting megalithic stones using GIS applications. While for the sloping megaliths, the least cost path analysis (LCPA) was used to produce the heritage trails. Finally, a megalithic stone heritage trails map with low, medium, and high capability levels could be produced. Figure 2 shows the method-ology of this study.

Figure 2.

Research methodology.

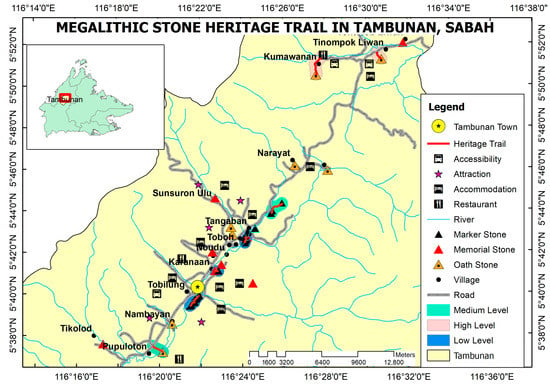

The potential tourists in this study would be for those who like nature, culture and history. By integrating the background story with the location of the megaliths, it will mo-tivate the tourists to follow the heritage trail to know more about the Kadazan Dusun cul-ture in Tambunan. This will provide unforgettable experiences while following the trails as the tourists will be able to see all the beautiful scenery surrounding the megalithic stones. The heritage trail map produced from this study will offer the tourists options that they can choose based on the levels of difficulty. The low level difficulty would be suitable for those tourists who prefer flat areas and easy access to the megalithic stones. The me-dium level difficulty would be for those who prefer longer distances but still on flat land. The high level difficulty are for those who like longer and more challenging routes with high slope areas as these will provide tourists with satisfaction when they reach the areas to see the stones and understand their background stories.

7. Study Tools

There were several tools that were used during fieldwork. Among these types of equip-ment include the Garmin GPSMAP® 64sc SiteSurvey which is used to observe the coor-dinates of the megalithic stones. Additionally, measuring tapes and rods were used to measure the height and width of megaliths. Cameras were also used to take still photo-graphs of the megalithic stones and other activities carried out throughout the fieldwork. Lastly, the ArcGIS software version 10.8 was used for the development of the spatial data in this study.

8. Analysis

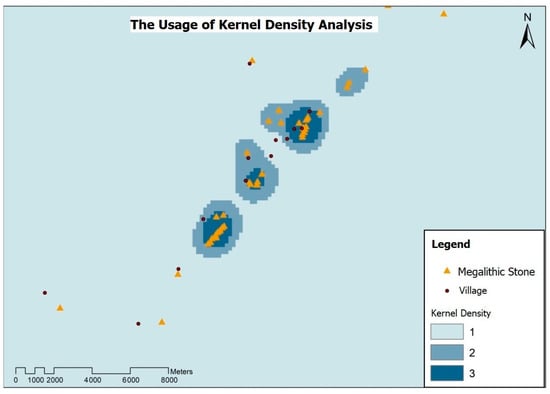

In this study, kernel density analysis was used to identify the focus areas of mega-lithic stones. This is to allow tourists to visit an area that has many megalithic stones within a short distance. The usage of kernel density analysis is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Usage of kernel density analysis. Note: 1, Low Kernel Density; 2, Medium Kernel Density; 3, High Kernel Density.

Next, buffering analysis was used to identify tourism elements adjacent to the mega-lithic stones. In this study, the distance from the megalithic stone location to the tourism element should be 500 m. It is important to ensure that tourists are interested in visit-ing the megalithic stone heritage trail with completeness from the aspect of tourism ele-ments.

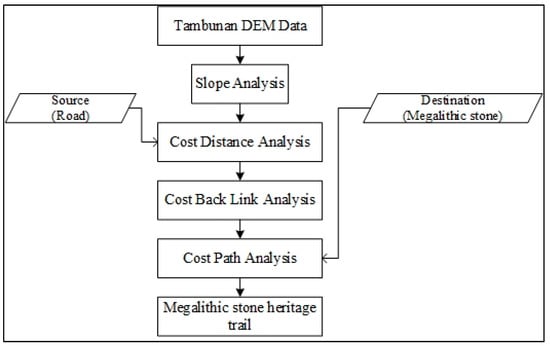

Then, the gradients for the megalithic stone locations were identified using slope analysis. Through slope analysis, megalithic stones were divided into low, medium, and high levels according to the gradient of the megalithic stone placement location. Lastly, the LCPA analysis was used to identify the least-cost routes to megalithic stones to pro-duce heritage trails. The way the LCPA analysis was carried out is shown in Figure 4. Tambunan DEM data were required to carry out the slope analysis. Next is to con-ductAfter this, a distance cost analysis was conducted using roads as sources and mega-lithic stones as destinations. This was followed by conducting backlink cost analysis and route cost analysis. Finally, the least-cost routes to megalithic stones which are also herit-age trails could be produced. This LCPA analysis was carried out on megalithic stones located in medium and high-sloping areas only. Whereas megalithic stones are also lo-cated on low slope areas, these megalithic stones are connected by lines using GIS appli-cations.

Figure 4.

LCPA analysis.

9. Results

In this study, the three resulting megalithic stone heritage trails included low-level heritage trails, medium-level heritage trails, and high-level heritage trails. The levels of these megalithic stone heritage trails were divided according to the gradient of the megalithic stone placement areas. These gradients were based on the classifications and gradient scores in the Gakenke District obtained from the study of Benineza et al. [42], as shown in Table 2. For low gradients, the gradient angle is 6–13, medium is 13–25, and high is 25–55.

Table 2.

Classification and slope score in Gakenke district.

The results of the low-level megalithic stone heritage trail in this study are shown in Figure 5. The blue-colored area is the low-level megalithic stone heritage trail. The red line is a heritage trail that connects nearby megalithic stones and has the same function and background. In this study, there were three trails of megalithic stone heritage located at low levels. These heritage trails involved megalithic stones from Tobilung Baru village, Karanaan village, and Tinompok village.

Figure 5.

Low-level megalithic stone heritage trails.

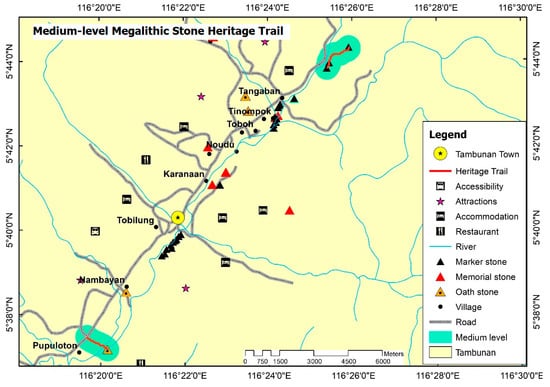

The medium-level megalithic stone heritage trails are shown in Figure 6. The medium-level megalithic stone heritage trail area are shown in light green; the red line shows the heritage trail connecting the megalithic stones. There are two megalithic stone heritage trails located on the medium-level megalithic stone heritage trails, namely in Pupuloton village and Mangi Pangi village. This medium-level megalithic stone heritage trail is located at a slope angle of 13–25.

Figure 6.

Medium-level megalithic stone heritage trails.

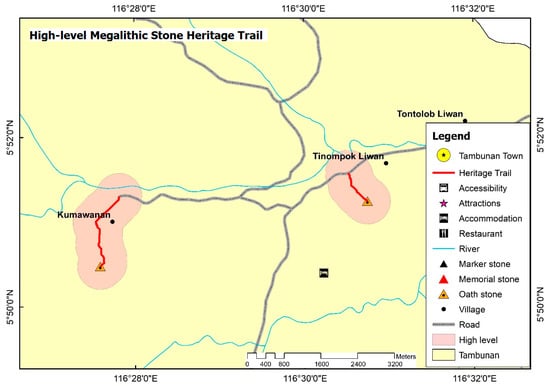

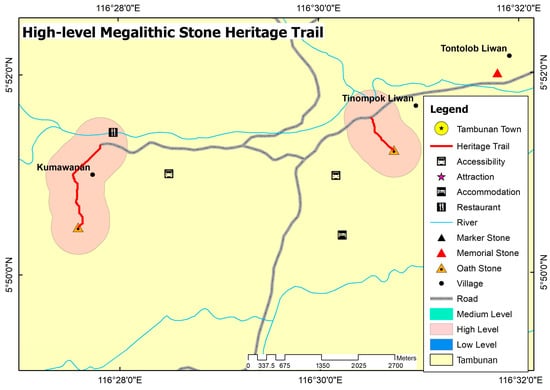

This study also produced heritage trails of high-level megalithic stones as shown in Figure 7. Areas of high-level megalithic stone heritage trails are shown in the red areas, while the red line in each high-level megalithic stone heritage trail area refers to the herit-age trail route to the megalithic stone. in this study, there were two high-level megalithic stone heritage trails involving Kumawanan village and Tinompok Liwan village.

Figure 7.

High-level megalithic stone heritage trails.

Finally, the three megalithic stone heritage trails produced were combined to pro-duce a megalithic stone heritage trail map in Tambunan. This heritage trail map contains low, medium, and high-level megalithic stone heritage trails. Figure 8 shows the megalith-ic stone heritage trail map for Tambunan.

Figure 8.

Megalithic stone heritage trail map in Tambunan.

10. Discussion

Based on the results of the study, there are three levels of megalithic stone heritage trails produced which are low, medium, and high. Megalithic stones that are categorized according to different levels of heritage trails have different backgrounds and functions. In the low-level megalithic stone heritage trail, there are three heritage trails produced. These three low-level megalithic stone heritage trails are located in Tobilung village, Karanaan village, and Tinompok village. The function of the megalithic stones found on the Karanaan heritage trails is as traditional boundary marker stones between wet paid fields owned by particular families over generations. This megalithic stone heritage trail in Ka-ranaan village consists of three megalithic stones. The three megalithic stones are the marker stones of padi fields and are located on the bunds in the rice fields. In the past, people used large stones as boundary marker stones because stones are stronger and last longer than smaller ones. The megalithic stones in Tobilung village, however, the line of megaliths runs parallel to the Pagalan River as did the ancient longhouses in the village, as the name Tobilung suggests. This indicates the megaliths in this village may have marked the route taken from Nunuk Ragang down the plain in ancient times. There are ten megalithic stones in the megalithic stone heritage trail in Tobilung village. Two of the megaliths have collapsed while eight others are still standing. In addition, nine megalithic stones in the heritage trail in Tobilung village are located in the padi field area both along the bunds and inside the padi field, while one stone is located at the edge of the residents’ houses. The megalithic stone heritage trail in Tinompok village involves eight megalithic stones. The function of the stones in the megalithic stone heritage trail in Tinompok vil-lage has boundary marker stones and a memorial stone indicating where a house once stood. Traditional houses in Tambunan, were built on stone uprights to prevent termite infestation. When an old disused house disintegrated, its stone uprights could still be seen until they fell over or were covered with scrub and soil. Memorial stones are also used to commemorate people who have died and who have no heirs, as well as those who have died and been buried in distant places. In addition, all three of these heritage trails are lo-cated on low-level slopes with a gradient angle of 6 to 13. Thus, tourists will find it easier to go along these trails. The walking time required to complete each low-level heritage trail is 10 to 15 min. This was estimated during on the ground measurement of the trail by the researchers. Along the way on the heritage trail, tourists can enjoy the beautiful scen-ery of the padi fields.

Heritage trails of medium-level megalithic stones are located in Pupuloton village and Mangi Pangi village. The only megalithic stone found on the medium-level heritage trail in the village of Pupuloton is an oath stone, namely the Lajau stone or Watu Lajau, named after the legendary tall and strong man Lajau who erected it. Watu Lajau is the tallest megalithic stone in Tambunan with a height of 2152 m. The edges of this megalith are marked with a series of notches showing the number of heads beheaded by warriors during a battle in the past, indicating that Watu Lajau was used as a peace-making oath stone at one time. The lower sheltered part of Watu Lajau also has blood stains from sacrificial animals slaughtered as atonement during peace-making ceremonies.

In the village of Mangi Pangi, there are three megaliths which are marker stones that mark the site of a Japanese military cemetery from World War II. Elderly villagers can re-call the arrival of Japanese soldiers walking through the bush into the village. Both of these megalithic stone heritage trails near Pupuluton and Mangi Pangi are located in an area with a slope angle of 12 to 25. The time required to complete this heritage trail is within 15 to 20 min on foot.

Finally, the high-level megalithic stone heritage trails are located in Kumawanan village and Tinompok Liwan village in the hilly area to the north of the District. Both of these heritage trails involve only one heritage trail in each village, namely to an oath stone in Kumawanan village and a protective stone in Tinompok Liwan village. The oath stone in Kumawanan village was erected for peace-making after battle involving five villages namely the villages of Madsango, Kumawanan, Pahu, Tenop, and Kirokot. Rituals and animal sacrifices as atonements were carried out in the past to ensure the peace of the vil-lages. Meanwhile, the protective stone in Tinompok Liwan village was erected to protect the villagers from disease outbreaks, especially smallpox epidemics. Visitors need to walk into the forest to reach the protective stone. Both of these megalithic stones are located on high-level slopes with gradient angles of 25 to 55. Individuals wishing to visit these two heritage trails need to have high endurance as the time required to reach the megalithic stones is in 45 min to one hour on foot. Therefore, for both of these high-level mega-lithic stone heritage trails, the journey is quite challenging and suitable for visitors who love adventure activities.

11. Conclusions

The act of preserving cultural heritage for the enrichment and education of younger generations in the present and future is important. Most tourism products take into ac-count places that have natural, original, and historical significance. However, some of these places are located in steep highland areas which makes the development of activi-ties as tourism products in such locations difficult. Therefore, the effectiveness of GIS has helped to solve this issue. LCPA analysis in GIS can identify routes that save costs, and energy, lower safety risks, and have various sloping routes. This helps in making high-altitude areas a potential tourism product. In this study, a megalithic stone heritage trail map involving low, medium, and high-slope areas in Tambunan District has been produced as a potential tourism product. This has not only overcome the problem of tour-ism product development in sloping areas but also as a step to preserve cultural heritage, that is the appreciation of the significance of megalithic stones in the District.

However, in order for these megalithic stone heritage trails to be fully utilised for tourism purposes, signage must be installed at suitable locations, promotion, advice about local customs and prohibitions regarding the megaliths, and responsible commercializa-tion must be conducted through leaflets or brochures and posting in the internet. Lastly, the most important thing is the participation of the local community itself to provide the background information about the area and the megalithic stones, and to ensure that these priceless historical objects are not damaged by irresponsible outsiders. This should in-volve all the relevant local authorities, from the village level, to the Tambunan Tourism Association, the Tambunan Native Court and the District Office. It will help with the cul-tural heritage sustainability of the local people.

Lastly, the findings of this study also show that by using GIS with different tech-niques and approaches, it will help greatly in producing a suitable megalithic stone her-itage trail map. Thus, this method will contribute in terms of knowledge advancement specifially in the cultural and science fields to produce an accurate heritage trail map that will be very beneficial to the people.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.V.E., B.B.B.B., J.P.-K. and A.H.B.P.B.; Methodology, K.T.S.; Software, K.T.S.; Investigation, Z.B.; Writing—original draft, K.T.S.; Visualization, K.T.S.; Supervision, O.V.E.; Funding acquisition, O.V.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UNIVERSITI MALAYSIA SABAH with grant no. SDN0056-2019 headed by Oliver Valentine Eboy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Oral consent was obtained from all individuals involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Universiti Malaysia Sabah for providing the fund scheme for this project and also would like to express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their efforts to improve the quality of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the Scientific Discourse on Cultural Sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culture for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/culture-sustainable-developmen (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Rzasa, K.; Ogryzek, M.; Kulawiak, M. Cultural Heritage in Spatial Planning. In Proceedings of the Baltic Geodetic Congress (Geomatics), Gdansk, Poland, 2–4 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feilden, B.M.; Jokilehto, J.I. Management Guidelines for World Cultural Heritage Sites. ICCROM. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/publication/management-guidelines-world-cultural-heritage-sites (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Navrud, H.L.S.; Ready, R.C. Valuing Cultural Heritage: Applying Environmental Valuation Techniques to Historic Buildings, Monuments and Artifacts. J. Cult. Econ. 2003, 27, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, S.; Marques, M. Valuing cultural heritage: The social benefits of restoring and old Arab tower. J. Cult. Herit. 2005, 6, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Asmilah, H.M.; Jusoh, H.; Mahmud, M.; Azman, H.; Ramli, S.; Tawil, N.; Bakar, R.A.; Zin, A.M. Aset pelancongan luar bandar dari lensa komuniti Lembah Beriah (Rural tourism assets from the community perspective of Lembah Beriah). Geografia 2017, 13, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd, J.K.; Gusni, S.; Jabil, M.; Rosazman, H.; Teuku, A.; Mustapa, A.T. Kearifan tempatan dan potensinya sebagai tarikan pelancongan berasaskan komuniti: Kajian kes komuniti Bajau di Pulau Mantanani, Sabah (Local knowledge and its potential as a community-based tourism attraction: A case study of a Bajau community in Pulau Mantanani, Sabah). Malays. J. Soc. Space 2015, 11, 112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sieng, K.T.; Eboy, O.V. Pemetaan Jejak Warisan untuk tujuan Pelancongan Lestari Menggunakan GIS di Tambunan: Heritage Trail Mapping for Sustainable Tourism Purposes Using GIS in Tambunan. J. Kinabalu 2021, 27, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Giering, A. Personal characteristics as moderators of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty—An empirical analysis. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieng, K.; Eboy, O. Ethnographic Patterns Map for Traditional Heritage of Kadazan Dusun Community Using GIS Analysis. Int. J. Geoinform. 2021, 17, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosyakov, S.V.; Sadykov, A. MGIS-based Cost Distribution Analysis of New Consumer Connections to An Urban Power Grid. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 18, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabyn, L.; Barnett, R. Population need and geographical access to general practitioners in rural New Zealand. N. Z. Med. J. 2004, 117, 996. [Google Scholar]

- Bagli, S.; Geneletti, D.; Orsi, F. Routeing of Power Lines through Least-Cost Path Analysis and Multicriteria Evaluation to Minimise Environmental Impacts. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, I.A.; Matori, A.N.B.; Yusof, K.B.W. Routing of road using Least-cost path analysis and Multi-criteria decision analysis in an uphill site Development. In International Conference on Civil, Offshore & Environmental Engineering (ICCOEE2012); Kuala Lumpur Convention Centre (KLCC): Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rifai, T. Tourism: Promoting Our Common Heritage and Fostering Mutual Understanding. In Proceedings of the InternationalCongress Religious Heritage and Tourism: Types, Trends and Challenges, Elche, Spain, 26–28 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Solheim, W.G., II; Gorman, C.F. Archaeological Salvage Program: Northeastern Thailand-First Season. J. Siam Soc. 1966, 54, 111–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, T.M.D. Study of Megalith in Vietnam and Southeast Asia. Soc. Sci. Inf. Rev. 2008, 2, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dougald, O.R.; Shewan, L.; Julie, V.D.B.; Samlane, L.; Thonglith, L. Megalithic Jar Sites of Laos: A Comprehensive Overview and New Discoveries. J. Indo-Pac. Archaeol. 2018, 42, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese, R. The Plain of Jars of North Laos: Beyond Madeleine Colani. Ph.D. Thesis, SOAS, University of London, London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nfn Hasanuddin. Temuan Megalitik dan Penataan Ruang Permukiman di Kabupaten Enrekang, Sulawesi Selatan; Balai Arkeologi: Makassar, Indonesia, 2011; Volume 13, pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Soedewo, E.; Koestoro, L.P.; Wiradnyana, K.; Oetomo, R.W. Profil Lembaga dalam Dinamika Hasil Penelitian Arkeologi di Sumatera Bagian Utara; Balai Arkeologi Medan: Medan, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, S.S.; Adnan, J.; Muhammad, T.H.; Zuliskandar, R. Penemuan Terkini Bukti Kebud. Megal. Dan Pengebumian Tempayan Di Sabah (Recent Discov. Megal. Cult. Urn Burials Evid. Sabah). J. Arkeol. Malays. 2018, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, I.H.N. On Slab-Built Graves in Perak. J. Fed. Malay States Mus. 1928, 7, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kamarul, B.B. Archaeological and Ethnological Survey of Megalitic Culture in Kuala Pilah, West Malaysia. University Microfilms International a Bell & Howell Information Company. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, Z. Archaeological Excavation of Three Megalithic Sites in Negeri Sembilan and Melaka. PURBA 1993, 12, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Harrisson, T. More Megaliths from Inner Borneo. Sarawak Mus. J. 1959, IX, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lamaichin, K. Tourism Elements; Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University: Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thammabut, P. Principles of Eco-Tourism; Srinakharinwirot University: Bangkok, Thailand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cantillon, Z. Urban Heritage Walks in a Rapidly Changing City. J. Herit. 2020, 15, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Eboy, O.V. Tourism Mapping: An Overview of Cartography and the Use of GIS. BIMP-EAGA J. Sustain. Tour. Dev. 2017, 6, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M.; Dahalan, N.; Hassan, F.; Suffarruddin, S.H. Heritage Tourism Trail Development in Kampung Luat, Perak: A Case Study. KATHA-Off. J. Cent. Civilis. Dialogue 2019, 15, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masdey, S.S.; Ramli, Z.; Bakar, N.A.; Ahmad, S. Megalithic Site in Negeri Sembilan. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. (IJMET) 2019, 10, 1159–1170. Available online: Http://Www.Iaeme.Com/Ijmet/Issues.Asp?Jtype=IJMET&Vtype=10&Itype=1 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Ibrahim, I.; Zakariya, K.; Wahab, N.A. Satellite Image Analysis along the Kuala Selangor to Sabak Bernam Rural Tourism Routes. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 117, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuddin. Kebudayaan Megalitik di Sulawesi Selatan dan Hubungannya dengan Asia Tenggara. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Macleod, N. The Role of Trails in The Creation of Tourist Space. JHT 2017, 12, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.; MacLeod, N. Packaging Places: Designing Heritage Trails Using an Experience Economy Perspective to Maximize Visitor Engagement. J. Vacat. Mark. 2007, 13, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpornpisal, C. Tourism Elements Influence the Decision Making in Traveling to Visit Phra Pathom Chedi, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand. Asian Adm. Manag. Rev. 2018, 1, 171–179. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3190064 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Total Population by Ethnic Group, (Malaysia Administrative District and State). Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthree&menu_id=NE9IWpoYXBlZXlWVjlleDEwR3BhZz09 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Dickman, S. Tourism: An Introductory Text, 2nd ed.; Hodder Education: Sydney, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Koentjaraningrat. Kebudayaan Jawa; PN. Balai Pustaka: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Benineza, G.; Rwabudandi, I.; Nyiransabimana, M. Landslides Hazards Assessment Using Geographic Information System and Remote Sensing: Gakenke District. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 389, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).