Decision Tree Analysis of Sustainable and Ethical Food Preferences of Undergraduate Students of Gastronomy and Culinary Arts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Nutrition

2.2. Ethical Food Preferences

- What is the order of importance of independent variables in classifying the behavioural intentions of gastronomy and culinary arts undergraduate program students towards sustainable and ethical food choices?

- What is the effect of the independent variables of sustainable food choice, ethical food choice, and perceived role and responsibility of chefs on the formation of behavioural intentions of gastronomy and culinary arts undergraduate program students towards sustainable and ethical food choice?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Validity and Reliability

3.2. Data Analysis

3.3. Findings

3.3.1. Demographic Data

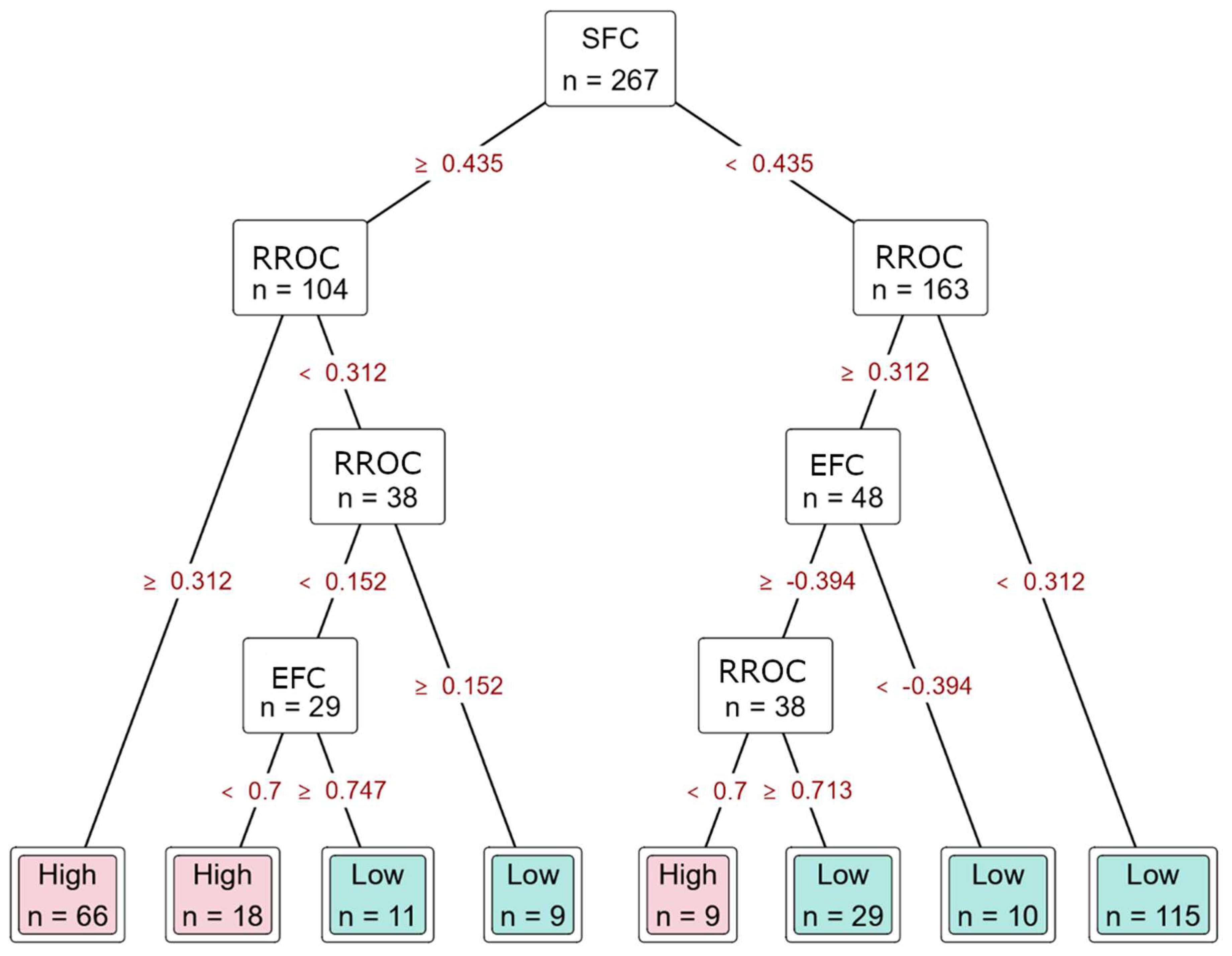

3.3.2. Decision Tree Classification

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Sustainable Food Choices

- SFC 1. It is good to support domestic agriculture by buying regional products.

- SFC 2. Health issues play an important role for me when I plan my menus.

- SFC 3. It is important to me to support local farmers when making purchase.

- SFC 4. I try to avoid food waste.

- SFC 5. I buy mainly local products.

- SFC 6. Genetically engineered food products are dangerous for human beings.

- SFC 7. I pay attention to fair trade labels.

- SFC 8. I would be willing to pay a higher price to support small growers from third-world countries.

- Ethical Food Choices

- It is important that the food I eat on a typical day

- AW 9. Has been produced in a way that animals have not experienced pain

- AW 10. Has been produced in a way that animals’ rights have been respected

- EP 11. Has been prepared in an environmentally friendly way

- EP 12. Has been produced in a way which has not shaken the balance of nature

- EP 13. Is packaged in an environmentally friendly way

- PV 14. Comes from a country I approve of politically

- PV 15. Comes from a country in which human rights are not violated

- PV 16. Has the country of origin clearly marked

- PV 17. Has been prepared in a way that does not conflict with my political values

- R 18. Is not forbidden in my religion

- R 19. Is in harmony with my religious views

- AW: Animal welfare

- EP: Environmental Protection

- PV: Political Values

- R: Religion

- Role and Responsibility of Chefs

- RES 20. Chefs have a responsibility to support sustainability through the products they purchase and the menus they prepare.

- RES 21. Chefs need to use ethical and sustainable food products.

- RES 22. Chefs have a responsibility to act ethically when purchasing food.

- ROC 23. Chefs have a role in disseminating sustainability awareness with the products they purchase and the menus they prepare.

- ROC 24. Chefs have a role in disseminating awareness of ethical food choice with the products they buy and the menus they prepare.

- ROC 25. Chefs set an example to the society with the products they buy and the menus they prepare.

- Behavioural Intention

- BI 26. I will try to buy regularly ethical and sustainable food when I enter the profession.

- BI 27. I plan to regularly purchase ethical and sustainable food when I enter the profession.

- BI 28. I will endeavour to regularly purchase ethical and sustainable food when I enter the profession.

References

- Evans, A. The Feeding of the Nine Billion Global Food Security for the 21st Century A Chatham House Report, London. 2009, p. 29. Available online: http://www.globalbioenergy.org/uploads/media/0901_Chatham_House_-_The_Feeding_of_the_Nine_Billion.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Godfray, H.C.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbear, C.; Friel, S. Food systems and environmental sustainability: A review of the Australian evidence. In National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health Working Paper; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C.S.; Bruulsema, T.W.; Jensen, T.L.; Fixen, P.E. Review of greenhouse gas emissions from crop production systems and fertilizer management effects. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 133, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerfeld, D. How We Got Here, and Where We Need to Go: The Bitter Fight About Meat and Climate. In Our Carbon Hoofprint; Mayerfeld, D., Ed.; Food and Health; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.J.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change through Livestock—A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Friel, S.; Barosh, L.; Lawrence, M. Towards healthy and sustainable food consumption: An Australian case study. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics a European Perspective: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, T.; Gardner, G.T.; Gilligan, J.; Stern, P.C.; Vandenbergh, M.P. Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 18452–18456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, T.; Speight, D. Cooking up diverse diets: Advancing biodiversity in food and agriculture through collaborations with chefs. Crop Sci. 2019, 59, 2381–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santich, B. Sustaining Gastronomy. In Proceedings of the Eighth Symposium on Australian Gastronomy: Sustaining Gastronomy, Adelaide, Australia, 28–30 September 1994; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J.R. Introduction to Hospitality, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, R.; Mandabach, K.; Thibodeaux, W.; VanLeeuwen, D. A multi-lens framework explaining structural differences across foodservice and culinary education. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Chefs as Agents of Change. FAO and UNESCO Collaboratıon on Food and Culture. 2019. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca3715en/ca3715en.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Soskolne, D. Cooking Schools: Towards a Holistic Approach. Master’s Thesis, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 2011. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- La Lopa, J.; Ghiselli, R.F. Back of the house ethics: Students must be taught not to give into the unethical behavior they may see or be asked to do during internships or in their careers. In Chef Educator Today; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Caraher, M.; Lange, T.; Dixon, P. The influence of TV and celebrity chefs on public attitudes and behavior among the English public. J. Study Food Soc. 2000, 4, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batat, W. Pillars of sustainable food experiences in the luxury gastronomy sector: A qualitative exploration of Michelin-starred chefs’ motivations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.R.; Cowee, M.W. Direct marketing local food to chefs: Chef preferences and perceived obstacles. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2009, 40, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, M.; Umberger, W.J. Assessing consumer preferences for country-of-origin labeling. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2005, 37, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeman, M.; Väänänen, M. Measurement of ethical food choice motives. Appetite 2000, 34, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable food consumption: An overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude—Behavioral ıntention gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csutora, M.; Vetőné Mózner, Z. Consumer income and its relation to sustainable food consumption—Obstacle or opportunity? Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 21, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazilian, M.; Rogner, H.; Howells, M.; Hermann, S.; Arent, D.; Gielen, D.; Steduto, P.; Mueller, A.; Komor, P.; Tol, R.S.J.; et al. Considering the energy, water, and food nexus: Towards an ıntegrated modelling approach. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7896–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Dietary Guidelines and Sustainability. 2010. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/background/sustainable-dietaryguidelines/en/#:~:text=Sustainable%20diets%20are%20protective%20and,2010%2C%20Sustainable%20Diets%20and%20Biodiversity (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Baldwin, C.; Wilberforce, N.; Kapur, A. Restaurant and food service life cycle assessment and development of a sustainability standard. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, A.; Buchli, J.; Göbel, C.; Müller, C. Food waste in the Swiss food service industry–Magnitude and potential for reduction. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, W.; Sloan, P.; Simons-Kaufmann, C.; Fleischer, C. A review of restaurant sustainable indicators. Adv. Hosp. Leis. 2010, 6, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Garg, A.; Prasad, S. Purchase decision of generation Y in an online environment. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckleberry-Hunt, J.; Tucciarone, J. The challenges and opportunities of teaching “generation Y”. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2011, 3, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Bonn, M.A. Generation Y consumers’ selection attributes and behavioral intentions concerning green restaurants. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2011, 30, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Calderón-Contreras, R.; Norström, A.; Espinosa, D.; Willis, J.; Guerrero Lara, L.; Pérez Amaya, O. Chefs as change-makers from the kitchen: Indigenous knowledge and traditional food as sustainability innovations. Glob. Sustain. 2019, 2, E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.; Lee, Y. What environmental factors influence creative culinary studies? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2009, 21, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.; Huber, A. A revolution in an eggcup? Food Cult. Soc. 2015, 18, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antalya Turizm İstatistikleri. 2022. Available online: https://www.turob.com/tr/bilgi-merkezi/istatistikler/2022/show/901/aralik-2022-antalya-turizm-istatistikleri (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Türkiye Tesis Kapasitesi. 2021. Available online: https://www.altid.org.tr/bilgi-hizmetleri/turkiye-tesis-kapasitesi-ekim-2021/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Muresan, I.C.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Brata, A.M.; Chereches, I.A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Dumitras, D.E.; Oroian, C.F.; Tirpe, O.P. Consumers’ attitude towards sustainable food consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in Romania. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldo, J.; Hsu, R.L.; Reid, T.; Righter, A.C.; Wolfson, J.A. Attitudes and beliefs about how chefs can promote nutrition and sustainable food systems among students at a US culinary school. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 25, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, B. Y kuşağı tüketicilerinin restoranlardaki sürdürülebilir uygulamalara yönelik tutumlarının ve davranışsal niyetlerinin ölçülmesi. In Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi; Balıkesir Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü: Balıkesir, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K. Researching internet-based populations: Advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. J. Comput.-Mediat. 2005, 1034, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P. An index of goodness-of-fit based on noncentrality. J. Classif. 1989, 6, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Freedman, D. How many variables should be entered in a regression equation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1983, 78, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, V.R. Optimal ratio for data splitting. Stat. Anal. Data Min. ASA Data Sci. J. 2022, 15, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Gursoy, D. Does offering an organic food menu help restaurants excel in competition? An examination of diners’ decision-making. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Moon, J.; Strohbehn, C. Restaurant’s decision to purchase local foods: Influence of value chain activities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioversity International. Mainstreaming Agrobiodiversity in Sustainable Food Systems: Scientific Foundations for an Agrobiodiversity Index; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://alliancebioversityciat.org/publications-data/mainstreaming-agrobiodiversity-sustainable-food-systems-scientific-foundations-0 (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Food for Soul. 2022. Available online: https://www.foodforsoul.it/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Chefs Manifesto. 2022. Available online: https://sdg2advocacyhub.org/intro_CM (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Hughes, M.H. Culinary Professional Training: Measurement of Nutrition Knowledge among Culinary Students Enrolled in a Southeastern Culinary Arts Institute. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2003. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Bölükbaş, R.; Sarıkaya, G.S.; Yazıcıoğlu, İ. Analysis of food waste and sustainability behavior in Turkish television cooking shows. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 24, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, P.; Wezel, A.; Veromann, E.; Strassner, C.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Kahl, J.; Bügel, S.; Briz, T.; Kazimierczak, R.; Brives, H.; et al. Students’ knowledge and expectations about sustainable food systems in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I.; Balázsné Lendvai, M.; Beke, J. The importance of food attributes and motivational factors for purchasing local food products: Segmentation of young local food consumers in Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.H.; Lu, M.Y. Evaluation of the professional competence of kitchen staff to avoid food waste using the modified delphi method. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 95% CI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Items | Abbrev. | Prediction | St. Err. | z-Value | p | Low | High |

| Factor 1 | SFC1 | λ11 | 0.679 | 0.022 | 30.633 | <0.001 | 0.635 | 0.722 |

| SFC2 | λ12 | 0.873 | 0.017 | 52.186 | <0.001 | 0.840 | 0.906 | |

| SFC3 | λ13 | 0.897 | 0.016 | 55.796 | <0.001 | 0.865 | 0.928 | |

| SFC4 | λ14 | 0.795 | 0.018 | 44.906 | <0.001 | 0.760 | 0.830 | |

| SFC5 | λ15 | 0.800 | 0.017 | 47.704 | <0.001 | 0.767 | 0.833 | |

| SFC6 | λ16 | 0.678 | 0.021 | 32.794 | <0.001 | 0.638 | 0.719 | |

| SFC7 | λ17 | 0.796 | 0.018 | 43.064 | <0.001 | 0.760 | 0.832 | |

| SFC8 | λ18 | 0.818 | 0.019 | 44.133 | <0.001 | 0.781 | 0.854 | |

| 95% CI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Items | Abbrev. | Prediction | Standard Error | z-Value | p | Low | High |

| Factor 1 | AW9 | λ11 | 0.969 | 0.007 | 136.921 | <0.001 | 0.956 | 0.983 |

| AW10 | λ12 | 0.983 | 0.007 | 136.921 | <0.001 | 0.969 | 0.997 | |

| Factor 2 | EP11 | λ21 | 0.996 | 0.005 | 195.58 | <0.001 | 0.986 | 1.006 |

| EP12 | λ22 | 0.964 | 0.005 | 183.348 | <0.001 | 0.954 | 0.975 | |

| EP13 | λ23 | 0.980 | 0.005 | 191.745 | <0.001 | 0.970 | 0.990 | |

| Factor 3 | PV14 | λ31 | 0.837 | 0.013 | 64.536 | <0.001 | 0.812 | 0.862 |

| PV15 | λ32 | 0.920 | 0.012 | 77.315 | <0.001 | 0.897 | 0.944 | |

| PV16 | λ33 | 0.888 | 0.013 | 69.544 | <0.001 | 0.863 | 0.913 | |

| PV17 | λ34 | 0.703 | 0.017 | 41.084 | <0.001 | 0.670 | 0.737 | |

| Factor 4 | R18 | λ41 | 0.999 | 0.038 | 26.455 | <0.001 | 0.925 | 1.073 |

| R19 | λ42 | 1.000 | 0.038 | 26.455 | <0.001 | 0.926 | 1.074 | |

| 95% CI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Items | Abbrev. | Prediction | Standard Error | z-Value | p | Low | High |

| Factor 1 | RES20 | λ11 | 0.957 | 0.012 | 77.282 | <0.001 | 0.933 | 0.982 |

| RES21 | λ12 | 0.959 | 0.012 | 77.001 | <0.001 | 0.934 | 0.983 | |

| RES22 | λ13 | 0.869 | 0.015 | 58.175 | <0.001 | 0.840 | 0.899 | |

| Factor 2 | ROC23 | λ21 | 0.951 | 0.010 | 91.087 | <0.001 | 0.930 | 0.971 |

| ROC24 | λ22 | 0.971 | 0.010 | 93.287 | <0.001 | 0.950 | 0.991 | |

| ROC25 | λ23 | 0.903 | 0.011 | 83.208 | <0.001 | 0.881 | 0.924 | |

| Predicted | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | ||

| Observed | High | 26 | 2 |

| Low | 3 | 35 | |

| Average/Total | |

|---|---|

| Support | 66 |

| Accuracy | 0.924 |

| F1 Score | 0.924 |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient | 0.846 |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | 0.925 |

| Sensivity | 0.897 |

| Spesivity | 0.946 |

| Relative Importance | |

|---|---|

| SFC | 38.300 |

| RROC | 32.875 |

| EFC | 28.825 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Şahin, E.; Gök Demir, Z. Decision Tree Analysis of Sustainable and Ethical Food Preferences of Undergraduate Students of Gastronomy and Culinary Arts. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043266

Şahin E, Gök Demir Z. Decision Tree Analysis of Sustainable and Ethical Food Preferences of Undergraduate Students of Gastronomy and Culinary Arts. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043266

Chicago/Turabian StyleŞahin, Esra, and Zuhal Gök Demir. 2023. "Decision Tree Analysis of Sustainable and Ethical Food Preferences of Undergraduate Students of Gastronomy and Culinary Arts" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043266

APA StyleŞahin, E., & Gök Demir, Z. (2023). Decision Tree Analysis of Sustainable and Ethical Food Preferences of Undergraduate Students of Gastronomy and Culinary Arts. Sustainability, 15(4), 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043266