1. Introduction

This research is placed in the interdisciplinary context of emergency pedagogy and the geography of risk. In the 1940s and 1950s, researchers from the “Chicago School” promoted a new branch of geography, which dealt with the social dimension of risk: it was born from the field analysis of the American floodplains, focusing on strengthening of the damage resulting from floods, despite the massive sums spent on massive hydraulic defence works [

1]. As a result, scholars have come to the conclusion that no technical and engineering solution can definitively solve the problem relating to the risk of flooding if a significant involvement of local communities is not also considered [

2]. In the 1970s, the French School of Geography gave a name to this branch of geography defining it as “geography of risk” [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Focusing on the impact and responsibility of human factors, this branch of geography explores the social, institutional and economic dimensions of risk and how they intersect with the effects of extreme natural events that culminate in disasters [

9]. Therefore, an alternative approach has been developed to the issue, in which greater importance is placed on the incidence and direct responsibility of anthropogenic factors in calamitous events, up to the point of questioning the use of the expression “natural disasters”. In fact, disasters cannot be defined simply as natural, because they are processes born from the relationship of mutual co-implication between nature and society [

10], resulting from the interaction between an extreme natural phenomenon (such as, indeed, an earthquake, tsunami, hurricane, volcanic eruption, flood) and the territory on which it impacts. Often, in fact, when the territory has social, cultural, economic, environmental and institutional vulnerabilities, the extreme event turns into disaster [

11,

12,

13].

In this context, moreover, a new branch of geography called “geography of perception” [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] developed in the 1960s in North America, which, by focusing on the subjective elaboration of the environmental image, thus evaluates the perceived territory, taking into account some variables that make the representation different from individual to individual. The production of research in this field has stimulated collaboration between geographers, psychologists and pedagogists, with research and applications in the field; a large number of studies about geography of perception are the basis of research on disasters, the trend of which is called “hazard perception” [

22], which is part of the vast Disaster Studies [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Furthermore, the geography of risk and the geography of perception intersect with the pedagogy of emergency which, as Vaccarelli [

10] points out, can act as a key science on at least three fronts: the front of prevention and, therefore, risk reduction education [

28]; emergency management, in whose context it leaves room for the theme of educational care “both from an individual and a community perspective, directing its actions to the resilience of people and the needs of communities, which involve numerous ethical and political questions and which often refer to the category of resistance” [

28] (p. 348); moreover, “the front of post-emergency management, which often risks presenting itself as the chronicity of the emergency phase” [

28] (p. 348). Risk reduction education is closely related to sustainability education. To avoid breaking the dynamic balance between population, environment and resources [

29], which is the main cause of disasters, it is appropriate, in fact, to promote an education in sustainability, especially among young people, through which to understand the importance of a systemic approach that reconsiders the interactions between human beings and the environment, between physical and anthropogenic factors, useful for safeguarding the health of our planet [

11]. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all member states of the United Nations in 2015, “provides a shared model for the peace and prosperity of people and the planet, now and in the future” [

30]. At the centre are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), “which are an urgent call for action by all countries—developed and developing—in a global partnership” [

30]. It is recognized that eliminating poverty must go hand in hand with adopting strategies that improve health and education and that can reduce inequalities by stimulating economic growth, addressing climate change and preserving our oceans and forests [

30].

According to the UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction), although some hazards are natural and inevitable, the resulting disasters have almost always been caused by human actions and decisions. In fact, deepening this aspect, some scholars have found it useful to give the name to a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. The concept of Anthropocene, proposed by Crutzen and Stoermer [

31], highlights the pervasiveness of human activity in the dynamics of the Earth system [

32]. While in geology the recognition of a new geological epoch requires certain procedures and the identification of the so-called geological markers (golden spikes) to establish the beginning of the geological age, in the human and social sciences the Anthropocene has already initiated an intense debate focusing on processes and phenomena that connect human activity with the environment [

33,

34]. According to the definition attributed by the UNDRR, in fact, disasters occur when a natural or human-induced hazard impacts on a vulnerable territory, and whose population is vulnerable due to the poverty, exclusion or socially disadvantaged [

35].

Disasters have always marked the human and natural history of the planet. In particular, the 21st century has so far been characterized by various disasters linked not only to natural hazards, but also to hazards induced by human beings such as industrial accidents, terrorist attacks, economic crises, migrant emergencies, wars, conflicts which, although they are subject to international humanitarian law and national legislation are, however, wholly or predominantly induced by human activities and choices [

36]. Zoonotic diseases (SARS-CoV-1, MERS, Ebola, SARS-CoV-2) have also marked the current century and are hazards that turn into a “permanent” disaster of epic proportions when humans fail to anticipate and to prevent them [

11].

Among the disasters linked to natural hazards, it is worth mentioning some examples: (1) the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami; (2) Hurricane Katrina which hit New Orleans in 2005; (3) the earthquakes in central Italy in 2009 and 2016, in Haiti in 2005 and in Nepal in 2015; (4) the 2023 earthquakes in Turkey and Syria. These were extreme natural phenomena which, by impacting on a vulnerable territory, generated disasters with a large number of victims and significant economic losses [

11].

Climate change is also reaching an ever-greater media level due to its increasingly evident effects (such as, for example, the melting of glaciers, the loss of biodiversity, waves of frost and heat, etc.) and the increasingly pressing need of solutions. On 20 November 2022, the final document of the COP27 Climate Change Conference held in Sharm El-Sheikh was approved [

37]. This is an annual meeting of the United Nations to define the objectives to be achieved in relation to climate change. The agreements made are the subject of scientific debate, because, while underlining the importance of the transition to renewable sources and the desire to eliminate subsidies to fossil fuels, only the reduction of coal-fired electricity production is required, not elimination, as, instead, several scientists had asked. The goal of keeping global warming within 1.5 degrees of pre-industrial levels remains confirmed, but this was the major achievement of COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. The main result obtained concerns the establishment of a fund for “Loss and Damage” [

37], or resources to draw on to remedy the damage and losses caused by the climate in developing countries most vulnerable to extreme weather events. The terms “mitigation” and “adaptation” appear in the final document, but there are no substantial indications on how to reduce emissions; countries that have not yet done so are suggested (without obligation) to respect the limits imposed in previous assemblies. Taking what emerges positively from COP27, it is possible to state that, for the first time, emphasis was placed on the damage that the countries of the south of the World suffer as a result of climate change.

The future scenarios in Italy, compared to the current situation, are not comforting; the effects of climate change in the Mediterranean area in general and in Italy in particular, may have negative effects for practically all sectors of economic interest: e.g., water, ecosystems, food, coastal areas, etc. [

38]. Despite the high climate risk, the perception and awareness of it are still not significantly high. Particularly, it is worth mentioning the most recent works on climate change perception pertinent to the objectives of this contribution. Antronico et al. [

39] carried out a study on the perception of climate change by a sample of the population of Calabria (southern Italy), according to which the perception varies in relation to contextual factors, including media communication, socio-demographic characteristics of the interviewees, knowledge and education, economic and institutional factors, personal values and, finally, psychological factors and experience. Marincioni [

38] carried out a study on perception of climatic risk and adaptation processes in Italian communities, dwelling on similarities and differences related to geographical location. In this work, Marincioni also clarifies the specific terminology of Disaster Studies. The study by Campo-Pais et al. [

40] found, in a survey on the perception of climate change in Ontinyent (Spain), on the other hand, that the conceptual and stereotypical errors of students, in the different stages of education, vary according to the type (climate, meteorological conditions, climate change, landscape) and education cycle (primary, secondary, university). Winter et al. [

41] conducted a qualitative study in Austria with a questionnaire using a sample of 80 secondary school students and 18 teachers. The results indicated that both groups do not feel adequately prepared in their possible role as “agents of change” as, both at the systemic and programmatic levels, it is necessary to strengthen training on these global challenges. A study conducted in Rajouri (India) by Zeeshan et al. [

42] sought to explore the level of awareness among school students and their participation in actions and advocacy on climate change, taking into account the type of school (private versus public), location (urban versus rural), the level of education (secondary versus higher secondary) and gender. The questionnaire received 717 responses, of which 27% showed a high awareness of climate change, 60% were very proactive in defence and 88% were willing to be involved in actions concerning their environment. However, the students most aware of climate change were not involved in adaptation and mitigation actions.

The aforementioned studies have several aspects in common with the present research, and it is worth highlighting that community resilience, sustainability and social vulnerability to climate change are three concepts closely related to the study of social perception [

39]. In fact, investigating and understanding public perception, the collective imagination and awareness of a community are necessary preconditions for the purpose of promoting strategies that are useful for strengthening the resilience of the community, guaranteeing sustainability and decreasing social vulnerability [

11]. Most of the research on students’ perceptions of climate change reveals that it is necessary to implement educational programs aimed not only at promoting knowledge of content related to climate change, but also at action-orientation [

43,

44,

45] through an engagement that can project the image of a challenge to be faced in which everyone can offer their own contribution in mitigation and adaptation.

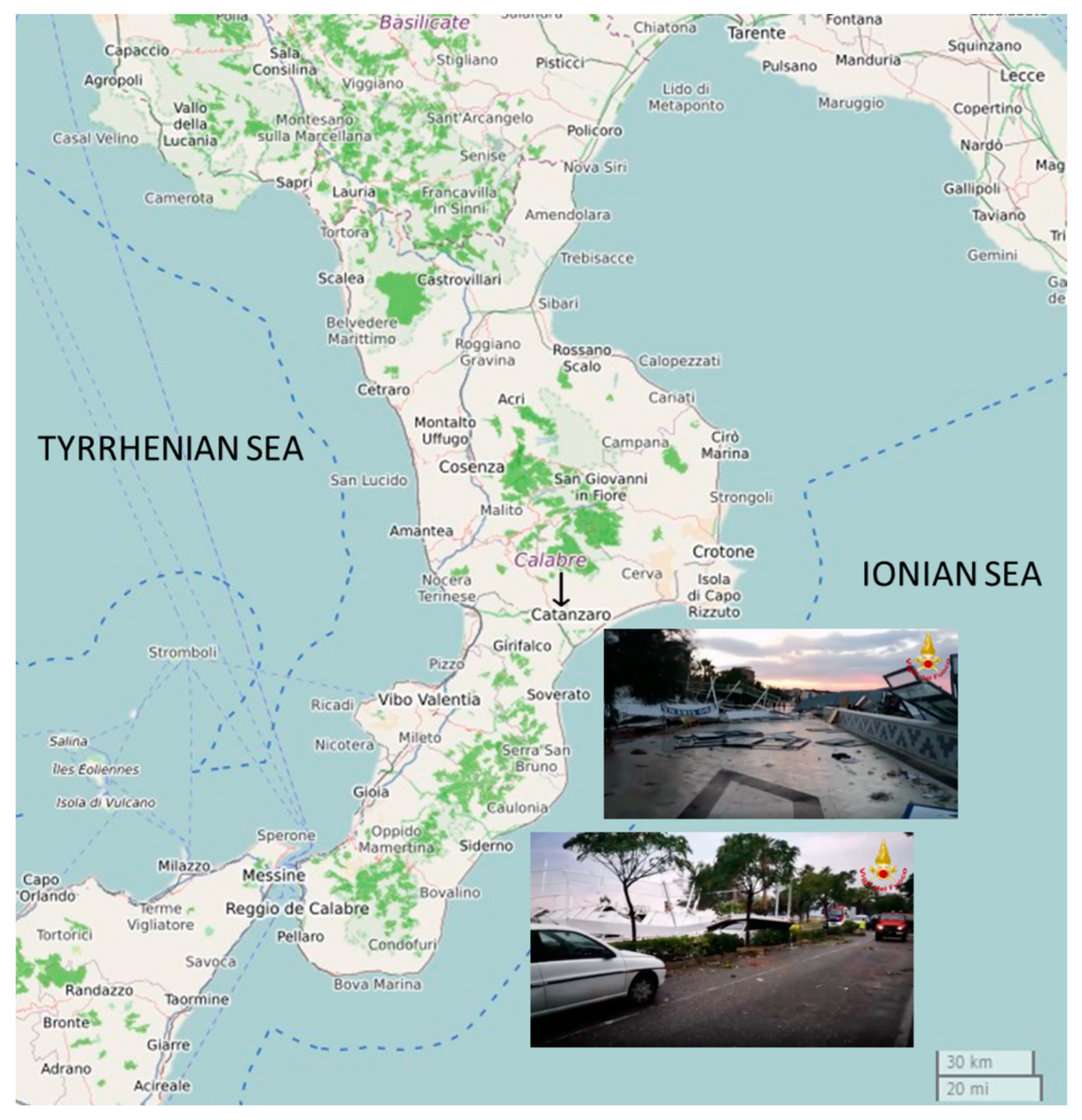

This contribution, therefore, proposes a study on how young people aged between 16 and 18 who live in the capital of Calabria, Catanzaro, southern Italy, perceive climate change. Through ethnographic interviews, based on the use of an open questionnaire and on participatory observation conducted in a secondary school, an attempt was made to reconstruct the degree of awareness of the students interviewed regarding the climate change underway, asking them to indicate which are the forms of knowledge involved and the possible causes of the phenomenon, as well as the critical issues and solutions currently available, both locally and globally, to limit any irreversible damage. A multi-scale approach was used to allow respondents to respond by taking into account different points of view and to facilitate the development of possible comparisons. The interviews allow us not only to reconstruct the ways in which groups of young students look at a possible climate crisis, but also to reflect on the possible methods of intervention that may be useful or necessary in terms of training and communication of risks related to natural extreme phenomena and climate change.

4. The Case Study of Catanzaro (Calabria, Southern Italy): Presentation of Results

To the question “Do you think climate change is taking place today? If so, what effects is it causing on a global or local scale?”, almost all the students replied that climate change is taking place on a global level. As effects of climate change, the following are cited above all: global warming that causes the melting of glaciers, the increase in the ozone hole and the greenhouse effect on a global scale; on a local scale, on the other hand, according to some students “one of the main problems caused by climate change is the non-change of seasons and, consequently, the mismatch of the blooms for local trees and plantations and the disappearance of plant and animal species”. Among the global effects mentioned, other students focus on “the unleashing of disasters linked to extreme natural events, on the spread of deadly diseases”, “on the destruction of forests, subject to fires that kill the inhabitants” and, specifically, “on the rise in sea level that causes the flooding of various cities such as Venice and Budapest and the submergence of the islands”, “on the breakdown of the permafrost”, “on the lack of water resources and drought” and even “on the increase in migratory flows” (

Table 2). Another stimulating answer was given by a student who highlighted not only the effects reported above, but above all “the real risk of the disappearance of the human race”. A student points out that “on a local scale, climate change is perceived less because, by not paying the costs of environmental pollution created by ourselves, we do not realize the damage we have caused”. Other students are aware of the “irreversible change” to which our planet is subject: “it is undeniable that today there are unquantifiable changes in the climate, more or less significant, which lead us to deal daily with climatic conditions and atmospheric agents before now unknown”.

When asked “What do you think are the causes of climate change?”, most students attribute the causes of climate change to human factors; some students highlight “the human ignorance and recklessness that is seriously damaging the balance of our planet”. In this context, a student stresses that “the cause of climate change is the man who, despite being aware of the problem, does not react in any way or, in any case, in an almost useless way, due to his indifference”. Specifically, some refer to the disproportionate use of plastic, smog, deforestation, intensive farming, non-compliance with environmental standards by large companies, pollution of the seas and land and global overpopulation; “the fires that hit the Amazon forest, considered the lung of the Earth”. One group of students confused the causes of climate change with the effects and cited as the main cause pollution linked, for example, to waste collection not carried out diligently and irresponsible behaviour on the part of citizens.

When asked “What is the difference between climate and weather?”, few students knew the difference between climate and weather, most of them confusing the climate with the changing of the seasons or with “the weather of a certain area in a certain period”. Whoever gave the correct answer defined the climate by considering “the climatic characteristics of a territory over a rather long period” (

Table 2).

When asked “What actions should we take, as individuals, in our daily life to combat climate change?”, most of the students indicated several actions to be taken, including “having fewer children, reducing plastic, planting trees, reducing smog, using public transport, carrying out separate collection correctly”. Another specific and witty response indicated that “consumption should be limited, an aspect that can hardly be realized, especially by the will of the richer countries”. Other students focused on giving up the use of cars and on the opportunity to travel by bike or on foot (if the place to reach is not far). Several learners expressed the need, as a country system, to produce and enhance electric cars. Regarding the last question, “are national and international political actions in place sufficient to reduce climate change? In your opinion, what are the necessary and/or desirable measures to avoid a disaster linked to climate change?”, the students were divided between those who thought that there was no intervention or action in the national and international context to reduce climate change and those who, on the other hand, thought that political actions are taking place, but they are not enough, but “something is starting to move thanks to the demonstrations organized by Greta Thunberg” (

Table 2). As desirable measures, “a radical change in the behaviour and habits of all” is needed. The provocative and intelligent response of a student with ASD that these disasters can only be stopped with the “disappearance of human beings” is worthy of consideration [

11].

5. Discussion

Almost all students believe that climate change is taking place. These data are probably also connected to the influence of the mass media which, during the period in which the interviews were conducted, often focused attention on this issue, also stimulated by the contents of the events organized by Greta Thunberg. These initiatives, in fact, have raised public awareness and, above all, have increased the awareness of young people on the issue of climate change and have resulted in a social movement against climate change and anthropogenic activity, including political decisions, whose effects contribute to global warming [

11].

Looking at the phenomena associated with climate change on a global scale, according to the interviewees, the most frequent response was “the melting of glaciers”. This is perhaps due, in part, to the agenda setting effect of the main television and online media which, before the COVID-19 pandemic, often opened the news or front pages with news on climate change, citing the progressive melting of glaciers. However, this depends specifically on the influence of the space-time dimension and the geographic concepts of relational and relative distance [

39]. The melting of glaciers, in fact, normally concerns a spatial dimension far from the contexts and from the daily life experience of students. Therefore, it should be perceived as a distant phenomenon in time and space and from the direct experience of people. On the other hand, it is likely that media exposure (digital and television media) contributes to weakening the relational distance between students and the mental representation of this phenomenon, so that the melting of glaciers is perceived as the most distinctive feature of the environmental crisis. In another study conducted in Calabria by Antronico et al. [

39], this image of glacier melting associated with climate change also emerges as predominant and for the same reasons. The association with the spread of deadly diseases is also significant, the perception of which, in fact, anticipates what would soon happen with the arrival of a pandemic, because the zoonosis process at the origin of the spread of the virus is closely linked to the themes of safeguarding the environment and natural ecosystems, primary forests and biodiversity [

58].

Regarding the causes of climate change, the majority of students in this study attributed the responsibility for climate change to anthropogenic activities. This increase in awareness of the importance of anthropogenic factors, as they influence current climate change, is probably due to the global media effect of the various events promoted by Greta Thunberg in 2019, before the arrival of COVID-19, but also to the current debate on the introduction of a new geological era, the Anthropocene, characterized by an impact of anthropic actions on the environment so vast as to modify and upset the dynamics and natural balances of the planet.

Some differences exist in the answers to the third question, even though they highlight similar criticalities. Few students demonstrate that they know the difference between climate and weather: most do not make the right distinction between climate and the alternation of seasons.

On the possibility of acting capable of counteracting the effects of climate change, the students, with some exceptions, showed a certain degree of awareness, both about the possibility of intervening in this process, and about the strategies to be taken into consideration. Students consider the need to change consumption habits and lifestyles, reducing waste and focusing on greater respect for sustainability. In fact, in tune with the perceptions of students, the commitment of all citizens is required to achieve the sustainability goals promoted by the 2030 Agenda [

30]. It is mainly our habits and our daily behaviours that affect energy consumption the most. Saving energy, therefore, means reducing the impact that all our activities have on the environment; every action we take involves the consumption of energy, and this consumption has an environmental cost. CO

2 emissions can be drastically reduced by conscious citizens, through simple energy saving measures, sustainable use of materials and resources and sustainable mobility policies. It is, therefore, essential to educate in sustainability, teaching young people the skills, values and attitudes that make them aware in order to make important decisions for the protection of the planet based on the knowledge acquired. In addition, education for sustainable development allows one to take actions responsibly to safeguard the integrity of the environment, to promote an economy based on geoethics and to build a more equitable society for present and future generations.

Finally, the answers of the adolescents to the fifth question were divided with different frequencies, revealing, however, a certain mistrust: if half of the students interviewed even believe that national and international legislation useful for reducing climate change does not exist, the other half considers them insufficient, with the exception of the protest movements from below. In addition, some responses also converge in this failure regarding the ineffectiveness of public and media communication, perceived as unnecessarily alarmist as they are lacking in political action.

6. The Importance of Geography and Teaching Climate Change at School: Observations

In terms of school education, the training that allows conscious and active citizenship must also pass through environmental education and, in this context, geography can play a leading role. In this regard, it is no coincidence that one of the most heartfelt debates in Italy in the field of disciplinary reflection and practice concerns precisely the teaching of geography in the various levels of education. If the Italian National Guidelines, since 2007, have replaced the old ministerial programs and, in their most recent form of 2012 [

59], have reaffirmed the importance of the verticality of the curriculum in teaching the discipline, it is true that, starting from 2010, the presence of geography in secondary school has experienced a significant decrease [

48]. Following the Italian Gelmini reform of 2010, in fact, the teaching of geography in most school curricula was reduced in the number of hours per week, and its objectives were changed [

60] (p. 41). Following this reorganization, the discipline has remained as independent teaching only within the Economic Technical Institutes, with three hours a week in the two-year period of the Administration, Finance and Marketing (AFM) specialization and as a professional subject in the Tourist Institutes, with a distribution on the entire five-year period (three hours a week in the two-year period and two hours in the three-year period) and the denomination of “Tourist Geography” [

61] (p. 37). Three years later, the first post-contraction intervention took place, with Italian Law No. 128/2013 [

62], which partially remedied the absence of the teaching of the discipline in many school curricula: a weekly hour of “general and economic geography” was introduced as a strengthening of the educational offer to be included, at the discretion of the schools, in the first or second year of the course of study. The second intervention, on the other hand, dates back to 2017, when Italian Legislative Decree 61 on professional education [

63] entrusted the various schools with the division of four hours a week to be divided between history and geography in the two-year period. However, the application of this legislation was delayed by the fact that the guidelines were only disclosed in 2019. Furthermore, because the criteria to be used for assigning the related number of hours to the two disciplines were not clarified, in order to bridge the teaching needs, many institutions have chosen to allocate 3 h a week to teaching history and 1 to geography [

60]. As regards the distribution of geography hours in high schools, it should be noted that there is only one hour per week and, usually, teaching is assigned to the history teacher. Furthermore, in many high schools, this distribution for teachers was organized in two hours of history and one of geography, called “geohistory”. The term certainly gives rise to some misunderstandings as to the detriment of what it seems to indicate; it is not to be connected to the geographical reflection in a diachronic key, but rather to its use in the editorial field for commercial purposes. Some textbooks for the two-year period, in fact, bear the same denomination to facilitate the organization of the disciplinary contents proposed [

11]. The result is that many teachers and students refer to geography with the term “geohistory”, blurring the specificity of the two disciplines into a confused unicum. Without wishing to deny here the profound (and always possible) connections between the two, it is, however, appropriate to remember that both proceed from different epistemologies and practices which demonstrate their effectiveness also in terms of teaching, while maintaining their complementarity [

11].

Climate change is taught as an environmental, biological and historical sciences topic in secondary school in Italy. It is also included as part of the civic education program to raise students’ awareness of the importance of environmental protection and measures to prevent climate change. It is a fundamental theme, as we have seen, in the teaching of geography. According to the International Charter on Geographical Education [

64] (p. 10), “Geography is concerned with human–environment interactions in the context of specific places and locations and with issues that have a strong geographical dimension like natural hazards, climate change, energy supplies, migration, land use, urbanization, poverty and identity. Geography is a bridge between natural and social sciences and encourages the ‘holistic’ study of such issues”. Geography, dealing with the problem of risk, finds itself investigating this new relationship that no longer considers nature and culture as opposing elements; in fact, first the theme of sustainability, then of climate change, redrew the boundaries between the two concepts [

65]. Sustainability calls into question the connection between natural elements and human actions, highlighting how the environment, economy, society and culture must be systematically taken into consideration in territorial management [

65]. Geography in school has the task of making students literate in reading the world, offering multidisciplinary skills (analytical and interpretative) and knowledge (of processes and phenomena) on the issues of risk and climate change, which otherwise would remain unexplored. However, according to Puttilli, precisely because of the progressive decline of geography in teaching, this task of literacy must, even more, extend to the public debate and to society, to re-elaborate the educational role of geography on the territory as a whole, outside the school environment [

66]. On the other hand, something else is also required of the discipline: the dissemination and didactic task should in fact avoid simplifications and reductionisms, face the questions and problems that reality proposes in a creative and critical way and use the different tools in an equally conscious way as the other disciplines make available [

66]. Finally, geography helps to understand how the concept of risk in schools can no longer be treated only from the point of view of the “natural” dimension, but it is necessary to take into consideration cultural, social, institutional, environmental and economic vulnerabilities in order to educate students to a different vision of disaster, triggered by anthropic factors. Geography, from an educational point of view, can show how correct land management and planning can help reduce vulnerabilities and, consequently, also disasters related to natural hazards and climate change.

More specifically, if the study of the perception of risk linked to climate change constitutes a meaningful research area from a geographical perspective, the way in which adolescents consider any changes taking place is of particular interest [

48] (p. 149). Gubler, Brügger and Eyer [

67] have recently shown how justified such attention to younger people is, because not only in the future will they be able to witness the most evident (and dangerous) consequences of climate change, but also with respect to previous generations are more exposed to the public and media debate on environmental issues, even during their training courses. The result of a study carried out at Boyolali District, Indonesia, showed that students who attend school in the urban area have a higher understanding of global warming than those who attend school in rural area. Ninety-six percent of students believe that global warming is happening, and 35% of students understand that global warming is caused mostly by anthropic activities [

68]. An exploratory research conducted by Moswete et al. [

69] used a comparative cross-sectional research design and survey data to describe and compare undergraduate students’ behaviours and perceptions regarding climate change and environmental issues at the University of Botswana in Gaborone and the United States Naval Academy United States (USNA). Two patterns emerged: the first was a consistently high percentage difference between students in the US and Botswana on issues related to climate change, tourism and other environmental issues. Batswana students overwhelmingly shared similar perceptions on most issues, regardless of their discipline. The only difference between the perceptions of Botswana students majoring in Environmental Sciences and those majoring in Business is the impact of climate change on the future attractiveness of their area [

69].

In light of these studies, climate change issues should be integrated into courses, subjects or programs in universities or educational institutes of developed and underdeveloped world institutions. In this context, geography teaching, both in schools and universities, plays a key role in enhancing awareness of climate change and providing categories and conceptual tools for students.

7. Conclusions

Climate change is one of the most debated deep-time emergencies at various levels. Its impact on the dynamics of the Earth system, starting from the most purely scientific formulations, intertwines different discourses and rhetorics that reverberate both on the media and on society and also involve scholars of human and social sciences in the debate. These rhetorics contribute to (re)producing universes of meaning and values potentially capable of directing individual or collective actions. In this context, one of the areas of study currently richer in implications from a geo-anthropological perspective is the perception of the future by the younger generations in light of their current knowledge on the subject of climate change. By epistemological status, geography is configured as a synthetic science capable of observing and studying, in a systemic key, dynamics that require a holistic approach, often positioning itself at the confluence of other disciplines (primarily the social sciences) without superimposing different and complementary epistemologies. This makes vocation for applied approaches more understandable. Furthermore, considering that it is also a discipline taught in various school grades and that various environmental issues (and among these climate change) can be addressed synergistically in a multidisciplinary key, precisely geography—which has also seen, in recent years, a drastic reduction in the weekly number of hours of the Italian Secondary School—appears to strengthen the links between theoretical research and application for the benefit of both in order to respond to new contemporary needs and urgencies.

In addition to acting on climate change mitigation, it is important to enhance the focus on adaptation, which is the ability of societies to change behaviour to alleviate the adverse impacts of climate change and create new opportunities, in a continuous and dynamic process in which societies respond to changes of various kinds, from environmental, socio-economic and technological ones, to cultural, legislative, political, institutional, managerial and, more generally, governance ones [

70]. In this context, geography can provide the right tools and methodologies to address these approaches in a holistic and interdisciplinary way.

In fact, according to some studies, in addition to teaching content knowledge, other components are also important, such as the conditions of the political framework or the integration of the reflection of socially controversial visions and uncertain perspectives for the future in order to promote actions in favour of the climate by the students to favour a knowledge-action [

71]. Furthermore, the urgency of the topic, which translates into an immediate need for action orientation and high teaching effectiveness as well as direct involvement, can pose specific challenges for both teachers and students [

41], and only through a strengthening of the teaching of geography can they be promoted and satisfied.