The Effect of Destination Brand Identity on Tourism Experience: The Case of the Pier-2 Art Center in Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

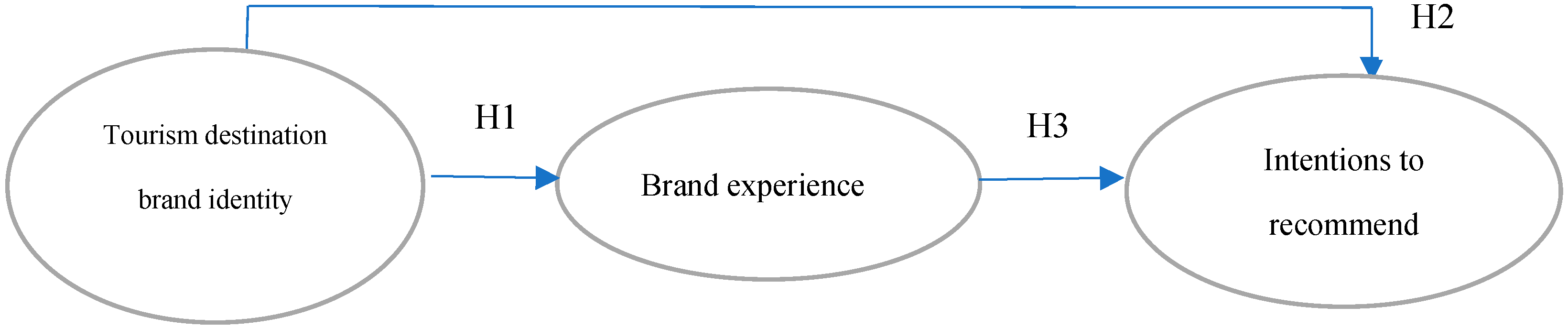

2. Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Destination Brand Identity of Art and Creative Tourism

2.2. Brand Experience and Intention to Recommend

3. Research Method

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling Method

3.2. Measures

4. Research Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Model Fit Indicators of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis

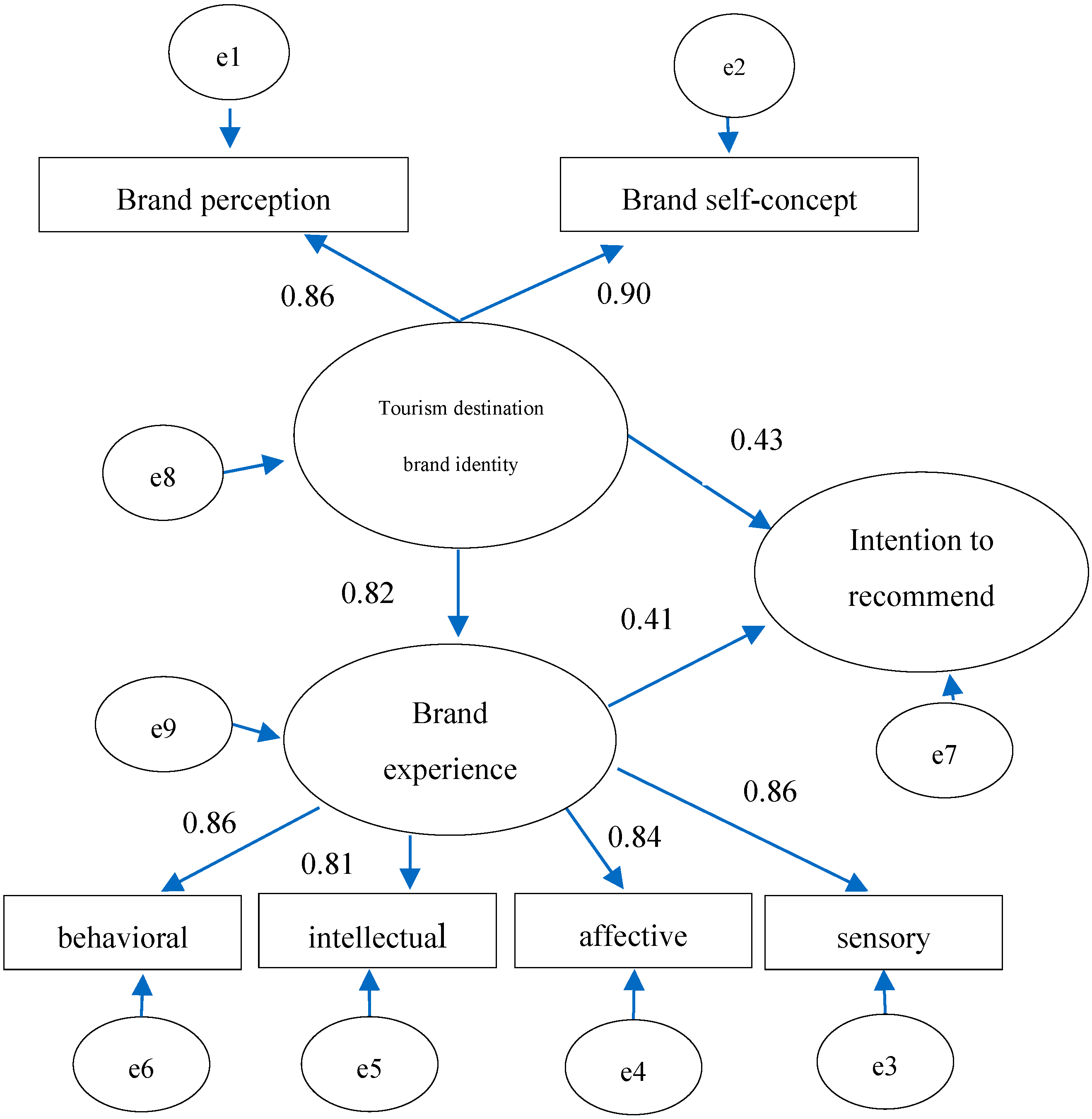

4.4. Structural Model Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Economic Impact Reports. 2022. Available online: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Escobar, A.L.; López, R.R.; Pérez-Priego, M.; de los Baños García-Moreno, M. Perception, Motivation and Satisfaction of Tourist Women on Their Visit to the City of Cordoba (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand, N.; Kitchin, P. Events Management: An International Approach; SAGE Publication Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Event Studies: Theory, Research and Policy for Planned Events, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.C.; Hsiao, Y.C.; Wu, R. A research on applying health concept to promote hot springs recreation industry. In Proceedings of the 2003 Health, Leisure, Tourism and Hospitality Conference Proceeding, Tainan, Taiwan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, J.; Meyer, D. Visitor attractions and events: Responding to seasonality. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.; Nunes, S.; Oliva, S.; Lazzeretti, L. Open Innovation, Soft Branding and Green Influencers: Critiquing ‘Fast Fashion’ and ‘Overtourism’. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakas, V.; Boukas, N. Extracting meanings of event tourist experiences: A phenomenological exploration of Limassol carnival. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. Using the brand experience scale to profile consumers and predict consumer behaviour. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Jordan, J.S.; Funk, D.; Rindinger, L.L. Recurring sport events and destination image perceptions: Impact on active sport tourist behavioral intentions and place attachment. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J.; Sørensen, F. Remembered experiences and recommend intentions: A longitudinal study of safari park visitors. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, C.; Levy, S.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Destination Branding: Insights and Practices from Destination Management Organizations. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dospinescu, N. The public relations events in promoting brand identity of the city. Econ. Appl. Inform. 2014, 1, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A.; Joachimsthaler, E. Brand Leadership: Building Assets in an Information Economy; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, X.; Li, S. How Does the Concept of Resilient City Work in Practice? Planning and Achievements. Land 2021, 10, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Country Brand Index. Country Brand Index, Future Brand. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2009, 17, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Country as brand, product and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soscia, I. Gratitude, delight, or guilt: The role of consumers’ emotions in predicting post-consumption behaviors. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 871–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, M.S. Strategic branding of destinations: A framework. Eur. J. Mark. 2009, 43, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, K. Place brand positions of a competitive set of near-home destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 60, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. Connecting with celebrities: Celebrity endorsement, brand meaning, and self-brand connections. J. Mark. Res. 2009, 13, 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, J.N. Strategic Brand Management: New Approaches to Creating and Evaluating Brand Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, M.; Cha, J.; Kim, J. The Effects of Tourism Storytelling on Tourism Destination Brand Value, Lovemarks and Relationship Strength in South Korea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Joachimsthaler, E. The brand relationship spectrum: The key to the brand architecture challenge. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.A. Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.A. Tourism branding in a social exchange system. In Tourism Branding: Communities in Action; Cai, L.A., Gartner, W.C., Munar, A.M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Konecnik, M.; Go, F. Tourism place brand identity: The case of Slovenia. J. Brand Manag. 2008, 15, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Cristòfol, F.J. Strategic Management of the Malaga Brand through Open Innovation: Tourists and Residents’ Perception. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Su, C.; Zhou, N. How do brand communities generate brand relationships? Intermediate mechanisms. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.; Clifford, C. Authenticity and festival foodservice experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 571–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. (Ed.) Tourism Planning and Destination Marketing; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, R.R. The effect of private club members’ characteristics on the identification level of members. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1996, 4, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.S.; Chou, S.F. Tourism strategy development and facilitation of integrative processes among brand equity, marketing and motivation. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokburger-Sauer, N.; Ratneshwar, S.; Sen, S. Drivers of consumer–brand identification. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Foreword. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.K.; Han, D.; Park, S. The effect of brand personality and brand identification on brand loyalty: Applying the theory of social identification. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2001, 43, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zach, F.J.; McGehee, N. Factors Influencing Exhibitor Satisfaction and Loyalty: A Meta-Analysis on the Chinese Exhibition Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B. Consultation builds stronger brands. In Tourism Branding: Communities in Action; Cai, L.A., Gartner, W.C., Munar, A.M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, A.; Zehir, C.; Kitapçı, H. The effects of innovated brand experiences, trust and satisfaction on building brand loyalty; An empirical research on global brands. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Brand management innovation: A construction of brand experience identification system. J. Appl. Sci. 2013, 13, 4477–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Eval. Model Fit 1995, 54, 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Introducing LISREL: A Guide for the Uninitiated; Introducing Statistical Methods Series; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.H.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigné, J.E.; Sanchez, M.; Sanchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationships. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rageh Ismail, A.; Melewar, T.C.; Lim, L.; Woodside, A. Customer experiences with brands: Literature review and research directions. Mark. Rev. 2011, 11, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappi, S.; Montanari, F. The role of social identification and hedonism in affecting tourist re-patronizing behaviors: The case of an Italian festival. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 74 | 36.8 |

| Women | 127 | 63.2 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <20 | 51 | 30.3 |

| 21~40 | 116 | 57.7 |

| 41~60 | 21 | 10.4 |

| 61 and over | 3 | 1.5 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 53 | 26.4 |

| Bachelor | 137 | 68.2 |

| Masters and above | 11 | 5.5 |

| Frequency of attendance | ||

| once | 116 | 57.7 |

| 2–3 times | 51 | 25.4 |

| More than 3 times | 34 | 16.9 |

| Income (NTD) | ||

| Less than 20,000 | 105 | 52.2 |

| 20,001–30,000 | 52 | 25.9 |

| 30,001–40,000 | 23 | 11.4 |

| More than 40,001 | 21 | 10.5 |

| Total | 201 | 100.00 |

| Variables | BI1 | BI2 | EX1 | EX2 | EX3 | EX4 | Rev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI1 | 10.00 | ||||||

| BI2 | 0.772 ** | 10.00 | |||||

| EX1 | 0.581 ** | 0.635 ** | 10.00 | ||||

| EX2 | 0.579 ** | 0.623 ** | 0.785 ** | 10.00 | |||

| EX3 | 0.540 ** | 0.615 ** | 0.657 ** | 0.653 ** | 10.00 | ||

| EX4 | 0.553 ** | 0.618 ** | 0.618 ** | 0.745 ** | 0.745 ** | 10.00 | |

| Rec | 0.650 ** | 0.616 ** | 0.647 ** | 0.614 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.555 ** | 10.00 |

| Mean | 30.595 | 30.488 | 30.950 | 30.889 | 30.739 | 30.678 | 30.829 |

| SD | 0.681 | 0.685 | 0.607 | 0.646 | 0.651 | 0.629 | 0.681 |

| Skewness | 0.045 | −0.049 | −0.243 | −0.145 | −0.112 | −0.163 | −0.010 |

| Kurtosis | −0.197 | 0.137 | 0.127 | −0.380 | −0.326 | 0.043 | −0.529 |

| Criteria | Indices | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. CMIN/DF | 1~5 | 4.46 |

| 2. GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.913 |

| 3. AGFI | ≥0.90 | 0.817 |

| 4. RMR | <0.08 | 0.016 |

| 5. RMSEA | ≤0.10 | 0.132 |

| Criteria | Indices | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.939 |

| 2. CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.951 |

| 3. IFI | ≥0.90 | 0.952 |

| 4. RFI | ≥0.90 | 0.899 |

| Criteria | Indices | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. PNFI | ≥0.50 | 0.570 |

| 2. PGFI | ≥0.50 | 0.578 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiang, C.-T.; Chen, Y.-C. The Effect of Destination Brand Identity on Tourism Experience: The Case of the Pier-2 Art Center in Taiwan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043254

Chiang C-T, Chen Y-C. The Effect of Destination Brand Identity on Tourism Experience: The Case of the Pier-2 Art Center in Taiwan. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043254

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiang, Chien-Ting, and Ying-Chieh Chen. 2023. "The Effect of Destination Brand Identity on Tourism Experience: The Case of the Pier-2 Art Center in Taiwan" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043254

APA StyleChiang, C.-T., & Chen, Y.-C. (2023). The Effect of Destination Brand Identity on Tourism Experience: The Case of the Pier-2 Art Center in Taiwan. Sustainability, 15(4), 3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043254