Community Development for Bote in Chitwan National Park, Nepal: A Political Ecology of Development Logic of Erasure

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Fortress Conservation, Community-Based Models and beyond

1.2. Nepal: Community Development in Buffer Zones and Protected Areas

1.3. Narratives of Political Ecology and Bote Marginalization

1.4. From Indigenous Knowledge to Moral Ecologies of Resistance

2. Materials and Methods

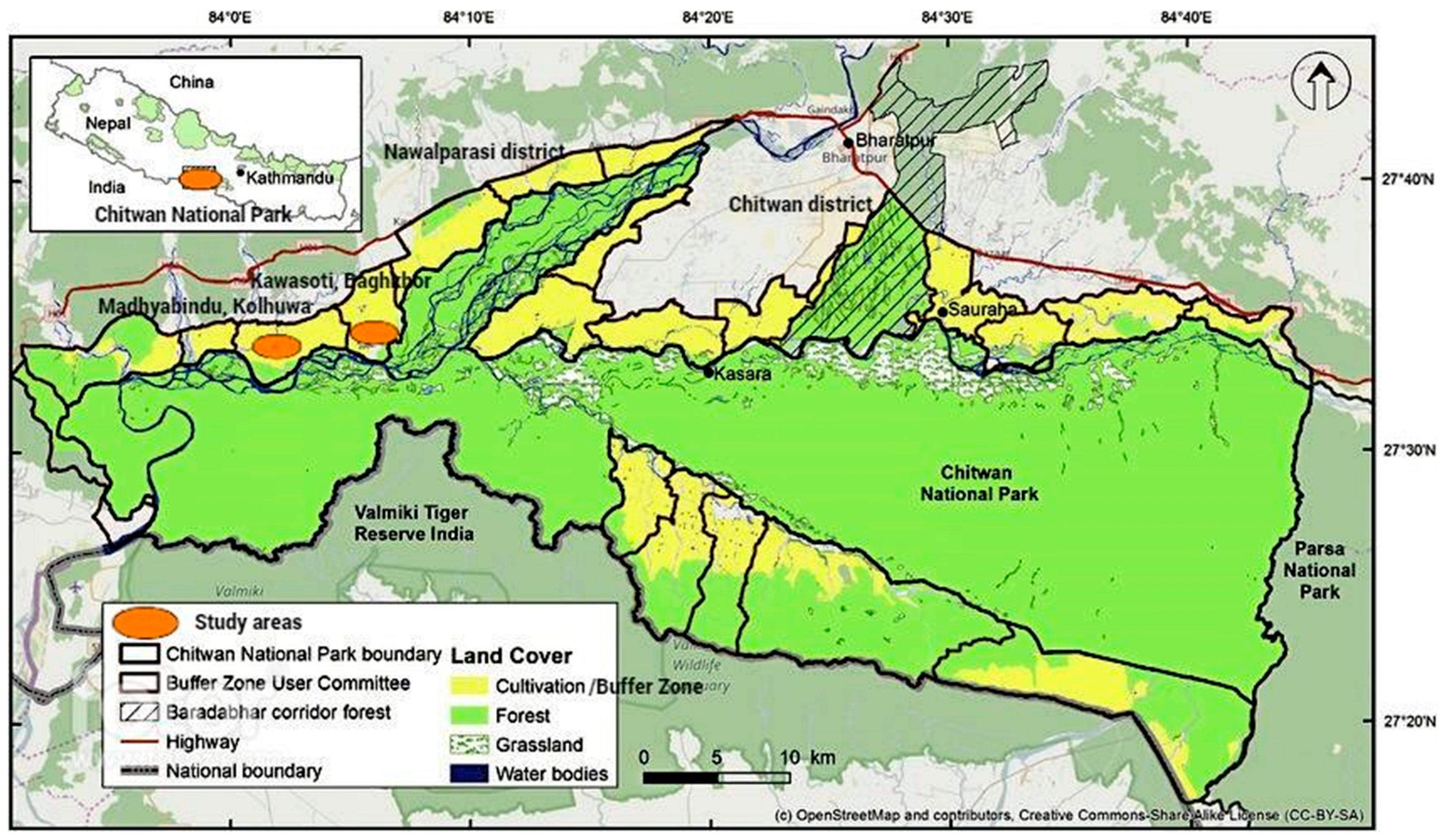

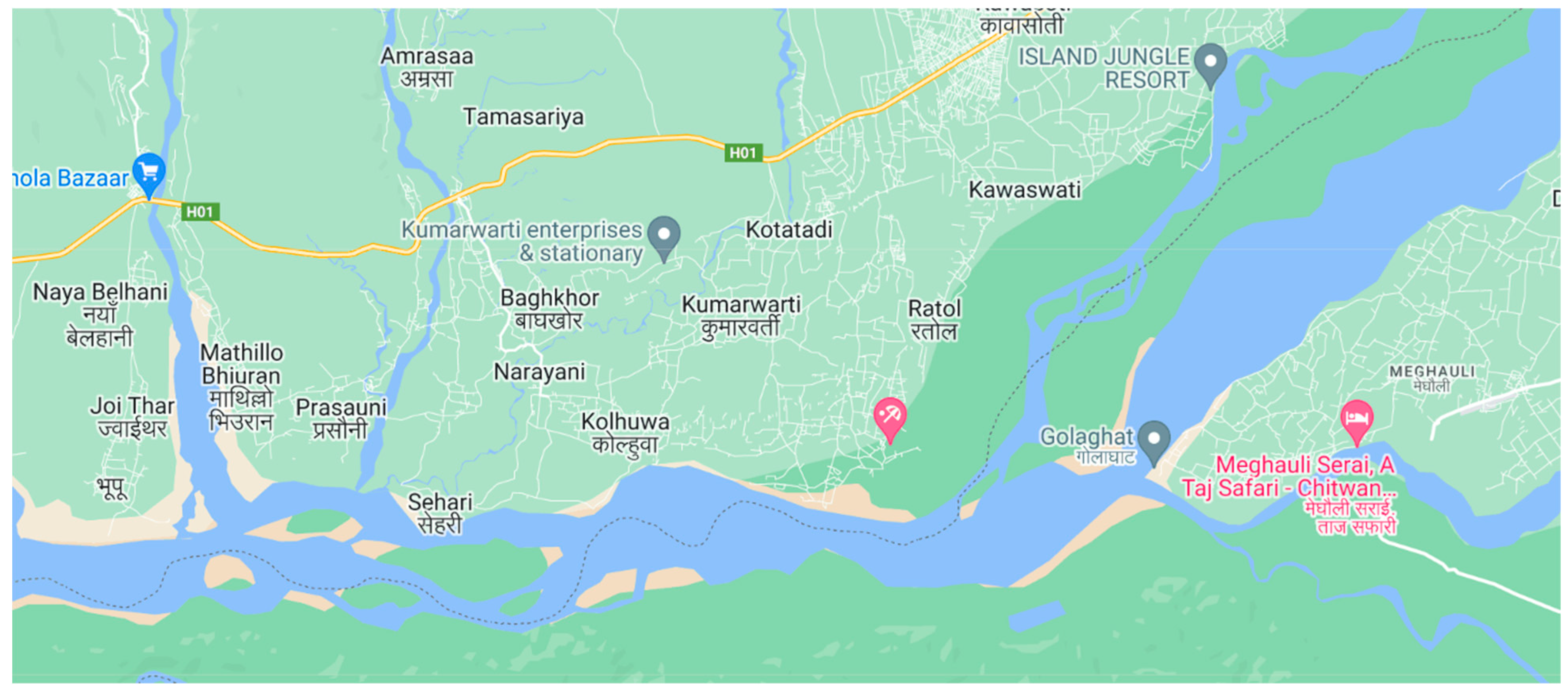

2.1. History and Political Ecology of the Chitwan National Park (CNP)

2.2. Bote People

2.3. Research Method: Critical Ethnography

2.3.1. Situated Ethnographic Interviews

2.3.2. Focus Group Discussions

2.3.3. Observation

2.3.4. Thematic Analysis

2.3.5. Ethics

3. Results: Traditional Livelihoods and the Environmental Ethics of Sustainability

3.1. Indigenous Practice of Gold Panning: Local Gold Mote Economy Banned

3.2. Precarious Livelihoods for Smallholders and Wildlife Incursions

3.3. Fishing and Fishponds

3.4. Gharial Crocodiles and Livelihoods

“Sir, I want to add something to this. Park authorities call us formally. They send us a letter to collect the eggs of the crocodile. A team of Bote collects the eggs and sends them to Kasara (a place where the crocodile eggs are collected for hatching). Eight to nine couples engage in collecting the eggs of crocodiles. It is difficult for the staff of the park to find the egg-laying area. We do have a major team there”.(Informant quote)

3.5. Bote Cosmovision

3.6. Policies, Practice, and Resistance of Bote Peoples

“We put the community at the centre to conserve and protect wild animals. In so doing, we have supported for livelihoods of local people. We support them through Community Forest User’s Group (CFUG). There are 72 households engaging in cattle farming, 401 in wool weaving, 76 in carpet weaving, some in mushroom farming, and some in banana farming. People have been trained and employed as nature guides or conservation guides for tourists. We have promoted micro-financing (saving and credit cooperative groups). There are four health posts and four veterinary clinics established. People have access to roads and water nowadays. In addition, we provide education to the children of local people and conduct awareness programmes on the conservation of wildlife”.(NNTC participant quote)

“We use local people for finding, capturing, and rescuing animals such as tiger, rhinos, elephants, and others, as they knew where these animals live, and what they do. Local people are used as guides”.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amnesty International. Violations in the Name of Conservation: “What Crime Had I Committed by Putting My Feet on the Land That I Own”; Amnesty.org: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa31/4536/2021/en/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Domínguez, L.; Luoma, C. Decolonising Conservation Policy: How Colonial Land and Conservation Ideologies Persist and Perpetuate Indigenous Injustices at the Expense of the Environment. Land 2020, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.M. Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in a Developing World, 3rd ed.; Adams, W.M., Ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2009; ISBN 2013206534. [Google Scholar]

- Castree, N.; Kitchin, R.; Rogers, A. A Dictionary of Human Geography; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780199599868. [Google Scholar]

- Bocking, S. Science and Conservation: A History of Natural and Political Landscapes. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 113, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauli-Corpuz, V.; Alcorn, J.; Molnar, A. Cornered by Protected Areas: Replacing ’Fortress’ Conservation with Rights-based Approaches Helps Bring Justice for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, Reduces Conflict, and Enables Cost-Effective Conservation and Climate Action; Rights & Resources Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Siurua, H. Nature Above People: Rolston and “Fortres” Conservation in the South. Ethics Environ. 2006, 11, 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemunta, N.V. Fortress Conservation, Wildlife Legislation and the Baka Pygmies of Southeast Cameroon. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, G. Community-Based Development Planning. Third World Plann. Rev. 1981, 3, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Development; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0195211294. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Beyond “Whose Reality Counts?” New Methods We Now Need? Stud. Cult. Organ. Soc. 1998, 4, 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Mansuri, G.; Rao, V. Community-Based and -Driven Development: A Critical Review. World Bank Res. Obs. 2004, 19, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, J.P.; Tsing, A.L.; Zerner, C. Representing Communities: Histories and Politics of Community-based Natural Resource Management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1998, 11, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pailler, S.; Naidoo, R.; Burgess, N.D.; Freeman, O.E.; Fisher, B. Impacts of Community-Based Natural Resource Management on Wealth, Food Security and Child Health in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobrevila, C. The Role of Indigenous Peoples in Biodiversity Conservation: The Natural but Often Forgotten Partners; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.M.; Hutton, J. Review: People, Parks and Poverty Political Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Boadu, E.S.; Ile, I.; Oduro, M.Y. Indigenizing Participation for Sustainable Community-Based Development Programmes in Ghana. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2021, 56, 1658–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, M.; Haider, W.; Stronghill, J. Conservancies in Coastal British Columbia: A New Approach to Protected Areas in the Traditional Territories of First Nations. Conserv. Soc. 2015, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorcroft, H. Paradigms, Paradoxes and a Propitious Niche: Conservation and Indigenous Social Justice Policy in Australia. Local Environ. 2015, 21, 591–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, D.M.S. Indigenous Livelihood Portfolio as a Framework for an Ecological Post-COVID-19 Society. Geoforum 2021, 123, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, C.; Granziera, A. A Handbook for the Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas Registry; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-92-807-3075-3. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, S. National Parks and ICCAs in the High Himalayan Region of Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, P.L. Living with the Problem of National Parks. Thesis Elev. 2018, 145, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Community-Based Conservation in a Globalized World. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15188–15193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccaro, I.; Beltran, O.; Paquet, P.A. Political Ecology and Conservation Policies: Some Theoretical Genealogies. J. Polit. Ecol. 2013, 20, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosfoguel, R. Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political-Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking, and Global Coloniality. TRANSMODERNITY J. Peripher. Cult. Prod. Luso-Hisp. World 2011, 1, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, A. Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America. Int. Sociol. 2000, 15, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Vijayakumar, G. (Eds.) Sociology of South Asia: Postcolonial Legacies, Global Imagineries; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-97029-1. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, C.J.; Robertson, I. Moral Ecologies: Conservation in Conflict in Rural England. Hist. Work. J. 2016, 82, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thing, S.J. Politics of Conservation, Moral Ecology and Resistance by the Sonaha Indigenous Minorities of Nepal. In Moral Ecologies: Histories of Conservation, Dispossessio and Resistance. Palgrave Studies in World Environment History; Griffin, C.J., Jones, R., Robertson, I.J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 37–58. ISBN 9783030061128. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel, S.; Harada, K.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, N.K. Ecotourism’s Impact on Ethnic Groups and Households near Chitwan National Park, Nepal. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, B.R.; Persoon, G.A.; Leirs, H.; Poudel, S.; Subedi, N.; Pokheral, C.P.; Bhattarai, S.; Gotame, P.; Mishra, R.; de Iongh, H.H. Contribution of Buffer Zone Programs to Reduce Human-Wildlife Impacts: The Case of the Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K.; Weber, K.E. A Buffer Zone for Biodiversity Conservation: Viability of the Concept in Nepal’s Royal Chitwan National Park. Environ. Conserv. 1994, 21, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, N.S.; Budhathoki, P.; Sharma, U.R. Buffer Zones: New Frontiers for Participatory Conservation? J. For. Livelihood 2007, 6, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bhusal, N.P. Chitwan National Park: A Prime Destination of Eco-Tourism in Central Tarai Region, Nepal Socio-Cultural Diversity Protected Areas and Eco-Tourism. Third Pole 2007, 5–7, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, B.R.; Wright, W.; Poudel, B.S.; Aryal, A.; Yadav, B.P.; Wagle, R. Shifting Paradigms for Nepal’s Protected Areas: History, Challenges and Relationships. J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, B.; Thapa, B. Buffer Zone Management Issues in Chitwan National Park, Nepal: A Case Study of Kolhuwa Village Development Committee. Parks 2015, 21, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T.; Satyal, P.; Dhungana, H.; Maskey, G. Brokering Justice: Global Indigenous Rights and Struggles over Hydropower in Nepal. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 40, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Raj, S. Improved Aquaculture for Sustainable Livelihood in Majhi Community: A Case from Bhimtar, Sindupalchowk. In Proceedings of the 8th IOE Graduate Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 5–7 June 2020; Volume 8, pp. 252–262. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, J.; Barman, B.K.; Murshed-E-Jahan, K.; Belton, B.; Beveridge, M. Can Aquaculture Benefit the Extreme Poor? A Case Study of Landless and Socially Marginalized Adivasi (Ethnic) Communities in Bangladesh. Aquaculture 2014, 418–419, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, T.B. Fisheries and Aquaculture Activities in Nepal. Aquac. Asia 2003, viii, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, J.N.; Kellert, S.R. Local Attitudes toward Community-Based Conservation Policy and Programmes in Nepal: A Case Study in the Makalu-Barun Conservation Area. Environ. Conserv. 1998, 25, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, A.; Bista, R.; Karki, R.; Shrestha, S.; Uprety, D.; Oh, S.E. Community-Based Forest Management and Its Role in Improving Forest Conditions in Nepal. Small-Scale For. 2013, 12, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, R.P. Protected Areas, People and Tourism: Political Ecology of Conservation in Nepal. J. For. Livelihood 2016, 14, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, S.B.; Furley, P.A.; Newton, A.C. Impacts of Community-Based Conservation on Local Communities in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 2765–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapp, J.R.; Lilieholm, R.J.; Leahy, J.; Upadhaya, S. Linking Attitudes, Policy, and Forest Cover Change in Buffer Zone Communities of Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 1292–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.P.; Goldey, P. Social Capital and Its “Downside”: The Impact on Sustainability of Induced Community-Based Organizations in Nepal. World Dev. 2010, 38, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, V. Forest Management Opportunities and Challenges in Nepal. Resour. Environ. 2011, 14, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, D.N.; Bulanin, N.; García-Alix, L.; Jensen, M.W.; Leth, S.; Madsen, E.A.; Mamo, D.; Parellada, A.; Rose, G.; Thorsell, S.; et al. The Indigenous World 2021, 35th ed.; IGWIA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; ISBN 978-87-93961-23-4. [Google Scholar]

- Yupsanis, A. ILO Convention No. 169 Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries 1989–2009: An Overview. Nord. J. Int. Law 2010, 79, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuja, J. Conservation and Discrimination: Case Studies from Nepal’s National Parks; IIED: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel, R.K.; Neupane, P.R.; Tiwari, K.R.; Köhl, M. Assessing the Sustainability in Community Based Forestry: A Case from Nepal. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, K.D.; Walter, P. Modernisation Theory, Ecotourism Policy, and Sustainable Development for Poor Countries of the Global South: Perspectives from Nepal. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2017, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, H.K. Park People Conflict Management and Its Control Measures in Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Int. J. Food Sci. Agric. 2019, 3, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thing, S.J.; Poudel, B.S. Buffer Zone Community Forestry in Nepal: Examining Tenure and Management Outcomes. J. For. Livelihood 2017, 15, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Fischer, H.; Shrestha, S.; Shoaib Ali, S.; Chhatre, A.; Devkota, K.; Fleischman, F.; Khatri, D.B.; Rana, P. Dark and Bright Spots in the Shadow of the Pandemic: Rural Livelihoods, Social Vulnerability, and Local Governance in India and Nepal. World Dev. 2021, 141, 105370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, E. Kincentric Ecology: Indigenous Perceptions of the Human-Nature Relationship. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S. Indigenous Peoples, Biocultural Diversity, and Protected Areas. In Indigenous Peoples, National Parks, and Protected Areas; Stevens, S., Ed.; A New Paradigm Linking Conservation, Culture, and Rights; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2014; pp. 15–46. ISBN 9780816530915. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, P. The Political Economy of Soil Erosion in Developing Countries; Routledge: London, UK, 1985; ISBN 9781317268383. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, P.; Brookfield, H. (Eds.) Land Degradation and Society, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1987; ISBN 9781315685366. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault, T. The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781315759289. [Google Scholar]

- Jessen, M.H.; von Eggers, N. Governmentality and Statification: Towards a Foucauldian Theory of the State. Theory Cult. Soc. 2020, 37, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, P. Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bishwokarma, D.; Thing, S.J.; Paudel, N.S. Political Ecology of the Chure Region in Nepal. J. For. Livelihood 2019, 14, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. The Political Ecology of Biodiversity, Conservation and Development in Nepal’s Terai: Confused Meanings, Means and Ends. Ecol. Econ. 1998, 24, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B. Living between Juniper and Palm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780198078524. [Google Scholar]

- Thing, S.J.; Jones, R.; Jones, C.B. The Politics of Conservation: Sonaha, Riverscape in the Bardia National Park and Buffer Zone, Nepal. Conserv. Soc. 2017, 15, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, D.; Nyaupane, G.; Shrestha, K.; Buzinde, C.; Thanet, D.R.; Vandever, V. Scalar Politics of Indigenous Waterscapes in Navajo Nation and Nepal: Conflict, Conservation and Development. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2021, 25148486211007853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, V.M. Indigenous Peoples and Biodiversity. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Saylor, C.R.; Alsharif, K.A.; Torres, H. The Importance of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Agroecological Systems in Peru. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2017, 13, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Reyes, J.E. Moral Ecology of a Forest: The Nature Industry and Maya Post-Conservation; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2016; Volume 4, ISBN 9780816531370. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, R.E. An Indigenous Critique: Expanding Sociology and Recognizing Unique Indigenous Knowledge. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 1047812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, J. Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal. Himalaya 1999, 19, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, U.R. An Overview of Park-People Interactions in Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1990, 19, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, J.T.; Kattel, B. Parks, People, and Conservation: A Review of Management Issues in Nepal’s Protected Areas. Popul. Environ. 1992, 14, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.; Chaudhary, S.; Chettri, N.; Kotru, R.; Murthy, M.; Chaudhary, R.P.; Ning, W.; Shrestha, S.M.; Gautam, S.K. The Changing Land Cover and Fragmenting Forest on the Roof of the World: A Case Study in Nepal’s Kailash Sacred Landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 141, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Nepal. State of Conservation Report: Chitwan National Park (Nepal) (N284); Government of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2022.

- Shrestha, U. Community Participation in Wetland Conservation in Nepal. J. Agric. Environ. 2013, 12, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, S. Crocodiles, Fishing Communities Battle for Survival in Nepal. Global Press Journal, 23 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, R.K. Bote Community Demands Unhindered Access to Fish in Chitwan Park Rivers Park. Kathmandu Post, 8 October 2021; 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Thanju, R.P. Advantages of Hydro Generation: Resettlement of Indigenous Bote (Fisherman) Families: A Case Study of Kali Gandaki “A” Hydroelectric Project of Nepal. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Small Hydropower-Hydro, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 22–24 October 2007; Volume 22, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Nepal Statistical Yearbook 2021, 18th ed.; Government of Nepal National Planning Commission: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2022; ISBN 978-9937-1-2767-7.

- Rosyara, K.P. Health and Sanitation Status of Bote Community. J. Inst. Med. Nepal 2009, 31, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, S. Working towards Environmental Justice: An Indigenous Fishing Minority’s Movement in Chitwan National Park, Nepal; International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2007; ISBN 978-92-9115-052-6. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, U.P. Livelihood Strategy of Bote Community: A Case Study of Bote Community of Patihani VDC of Chitwan. Dhaulagiri J. Sociol. Anthropol. 2010, 4, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; Volume 5, pp. 843–860. ISBN 9789811052514. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. Ritual and Social Change: A Javanese Example. Am. Anthropol. 1957, 59, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, M.; Tiwari, G.; Lahiri-Dutt, K. Artisanal and Small Scale Mining in India: Selected Studies and an Overview of the Issues. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2008, 22, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.P. Changing Dynamics of the Bote Communities in Sarlahi and Tanahun: A Comparative Study. Rupantaran Multidiscip. J. 2022, 6, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghale, S. A Vanishing Way of Life. Kathmandu Post, 27 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naharki, A.R. Collecting Gold from River Sand: A Profession That’s Disappearing. The Rising Nepal, 13 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Himalayan News. Service Botes Prepare to Search for Gold. Himalayan News, 15 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Limbu, S.; Rai, Y.; Majhi, C.; Gahle, D.; Thebe, A.; Magar, S.L. Violation of Indigenous Peoples’ Human Rights in Chitwan National Park of Nepal; Lawyers’ Association for Human Rights of Nepalese IPs (LAHURNIP) and National Indigenous Women Federation (NIWF): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, B.; Chand, N.; Shrestha, A.; Dhakal, N.; Karki, K.B.; Shrestha, H.L.; Bhandari, P.L.; Adhikari, B.; Shrestha, S.K.; Regmi, S.P.; et al. How Policy and Development Agencies Led to the Degradation of Indigenous Resources, Institutions, and Social-Ecological Systems in Nepal: Some Insights and Opinions. Conservation 2022, 2, 134–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastidar, S.G. Chitwan’s Bote People in a Changing World. Nepali Times, 31 October 2020; 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, H.; Dearden, P. Rethinking Protected Area Categories and the New Paradigm. Environ. Conserv. 2005, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norget, K. Surviving Conservation: La Madre Tierra and Indigenous Moral Ecologies in Oaxaca, Mexico. In New Natures: Critical Intersections for Environmental Management and Conservation in Latin America; School of American Research: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-García, V.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y.; Benyei, P.; Bussmann, R.W.; Diamond, S.K.; García-del-Amo, D.; Guadilla-Sáez, S.; Hanazaki, N.; Kosoy, N.; et al. Recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities’ Rights and Agency in the Post-2020 Biodiversity Agenda. Ambio 2022, 51, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Narrative | Meaning | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Degradation and marginalization | Natural resources are overexploited due to state intervention and modernization. | The modernization of Nepal, including tourism, abandonment of rural livelihoods, hydroelectricity, aquaculture ventures and state interventions supported by legislation on forests and parks (through PAs and BZs) has led to increased human presence and natural resource use. Responsibility, however, is shifted to unsustainable practices of traditional groups. |

| Conservation and control | Resources must be conserved and controlled at any cost. | The PAs and BZs underpinned by the National Forest and Wildlife Act (1973), as well as the later community-based approaches, adopt a neo-Malthusian logic of population control and conservation for tourism ends, which must be controlled by displacing people and encouraging bans on traditional livelihoods, and destructive interactions with nature. |

| Environmental subjects and identity | The emergence of a new group of people representing local people who engage in political actions. | NGO groups of various kinds have begun representing the grievances of local people. The repression of political action by minority groups is replaced by this representation. Other actors in this category include international organisations such as IGWIA. The degree and effectiveness of political action varies and may conflict with emerging indigenous leadership. |

| Environmental conflict and exclusion | The continuous conflict that exists between communities when a particular elite group controls resources through policy. | State-led interventions and policies have created conflicts between indigenous groups and other social groups, whereby the dominant population accuses indigenous communities of destroying the environment. Violence visited on indigenous groups by park authorities and the army is justified by indigenous belligerence. |

| Political objects and actors | Political and economic systems that are shown to be underpinned and affected by non-human actors with which they are intertwined. | The environment and its key actors, e.g., wildlife, nature, rivers, and forests, are the basis for local livelihoods and for the state in its efforts at modernization, e.g., eco-tourism. The actions of the state against groups is a response to the perceived threats to this environment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rai, I.M.; Melles, G.; Gautam, S. Community Development for Bote in Chitwan National Park, Nepal: A Political Ecology of Development Logic of Erasure. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032834

Rai IM, Melles G, Gautam S. Community Development for Bote in Chitwan National Park, Nepal: A Political Ecology of Development Logic of Erasure. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032834

Chicago/Turabian StyleRai, Indra Mani, Gavin Melles, and Suresh Gautam. 2023. "Community Development for Bote in Chitwan National Park, Nepal: A Political Ecology of Development Logic of Erasure" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032834

APA StyleRai, I. M., Melles, G., & Gautam, S. (2023). Community Development for Bote in Chitwan National Park, Nepal: A Political Ecology of Development Logic of Erasure. Sustainability, 15(3), 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032834