Abstract

The transportation industry is transitioning from conventional Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICVs) to Electric Vehicles (EVs) due to the depletion of fossil fuels and the rise in non-traditional energy sources. EVs are emerging as the new leaders in the industry. Some essential requirements necessary for the widespread adoption of EVs include sufficient charging stations with numerous chargers, less to no wait time before charging, quick charging, and better range. To enable a quicker transition from ICVs to EVs, commercial organizations and governments would have to put in a mammoth effort, given the low number of installed chargers in developing nations such as India. One solution to lower the waiting time is to have multiple vehicles charging simultaneously, which might involve charging two- and four-wheelers simultaneously, even though their battery voltage ratings differ. This paper begins by providing the details of the power sources for EV charging, the charging levels and connector types, along with the specifications of some of the commercial chargers. The necessity of AC-DC converters in EV charging systems is addressed along with the power quality concerns due to the increased penetration of EVs. Next, a review of the existing research and technology of isolated DC-DC converters for simultaneous charging of EV batteries is provided. Further, several potential isolated DC-DC converter topologies for simultaneous charging are described with their design and loss estimation. A summary of the existing products and projects with simultaneous charging features is provided. Finally, insight is given into the future of simultaneous charging.

1. Introduction

The primary mode of transportation in the world is petrol- and diesel-based vehicles. These vehicles use internal combustion engines (ICEs) to burn the fuel to run the vehicle. However, there are several issues with the use of ICEs. It has low fuel efficiency, higher operating cost, and harmful emissions [1]. Due to the emissions of ICEs, the resultant climate changes have led to the development of hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) and electric vehicles (EVs).

1.1. Methods of Obtaining Electricity for Charging

Conventionally, electricity is obtained from thermal, hydro, and nuclear power plants. While fossil-fuel-based thermal power plants can be used to produce power in mega-watt levels, they also produce harmful gases such as carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, and ash [2], which has led to a steady increase in the global temperature [3], and which in turn has caused the degradation of flora and fauna, and the health of humans. In addition, the depletion of fossil fuels is a significant threat to the continued use of fossil fuel-based power generation. The connection between emissions and fossil fuel depletion is a significant concern today [4]. While hydro plants do not lead to such an issue, the main problems with the hydro plant are related to the submergence of the areas surrounding the dam, the impact on the water resources, and the rainfall amount. The impact depends mainly on the dimensions of the hydro plant [5]. With nuclear power plants, the main issue is related to resource availability, the complexity of control, the potential risk of leakage, and waste disposal. Various nations have developed several policies to prevent nuclear disasters [6]. To prevent the issues resulting from the conventional sources, non-conventional energy sources have been introduced into the power generation sector. Among these resources, the solar photovoltaic (PV) system is being used due to abundant resource availability. Since solar panels can be integrated with vehicles, solar PV is an attractive option as a source to charge EVs. Nasr et al. [7] have comprehensively reviewed solar PV based converters for EV battery charging. Several non-isolated converters suitable for EV battery charging have been reviewed, along with gird integrated converters. The primary issue that needs to be addressed with the use of PV systems is the intermittency and variations of solar irradiance and temperature. The intermittency has been addressed by Jin et al. [8]. Energy optimization is necessary with the use of PV systems, as addressed by Al-Shahri et al. [9].

EVs, specifically battery electric vehicles (BEVs), have contributed to reducing pollution as they create no gas emissions. However, an important point to note is the power source for charging [10]. If coal-based power plants are used for power production to charge the battery, the burden on the system will be dominant. The positive environmental impact will be significantly higher when renewable energy resources are used [10]. Another issue that needs to be focused on with the increased use of EVs is the recycling and disposal of a battery that has been damaged or completed its life cycle. Yu et al. [11] have addressed the challenges in recycling Li-ion batteries and provided several suggestions to address recycling. If these issues are addressed effectively, the use of EVs can create a more positive impact on the environment.

EV research is experiencing a boom in the present day due to a renewed emphasis on reducing our carbon footprint [12], greenhouse gas emissions, and the depletion of fossil fuel resources. Several significant difficulties have gained attention due to the growing interest in EV use. These problems include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Power quality concerns due to EV charging;

- Low number of charging stations;

- Long waiting time before charging;

- Higher time for charging;

- Lower range of EVs.

Government policies outside the research community’s purview influence the number of charging stations. The EV range issue is related to the type, C-rate, and battery rating, which the battery manufacturers and researchers of battery technology usually address. Electrical engineering research is directly or indirectly interested in the challenges of power quality issues and reducing the waiting and charging times.

1.2. Charging Techniques for EV Batteries

The technology or method employed for charging depends on the battery chemistry. Generally, Lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries are used in EVs due to their high energy density, longer lifetime, and good electrochemical properties [13]. Several techniques for charging EV batteries have been recommended and reviewed by researchers for EVs. Shahjalal et al. [14] have provided the details of the various charging techniques for EV batteries. The charging methods could be conventional (slow) charging or fast charging. Conventional charging methods include constant current (CC) charging, constant voltage (CV) charging, and constant-current constant-voltage (CC-CV) charging. Several researchers have investigated the idea of reducing charging time by employing fast charging methods [15] such as flash charging [16], pulse charging [17,18], negative pulse charging [19], multistage current control protocol [20], variable current profile charging [21], boost charging [22], and other algorithm-based methods [23,24]. Hemavathi et al. [25] have provided details of the various conventional and fast charging methods with a qualitative comparison. In addition, the battery modeling has been provided with charging methodologies specific to various converters. Different charging levels have been described, along with the charging station architectures and fast charging topologies. The future trend of EV charging has been described to include smart charging, integration of renewable sources, wireless charging, and battery swapping. The authors have provided the road map of EV adaption. Research focus has also been shifted to address the degradation effects on the battery due to fast charging [26,27,28], its effect on the existing grid [29,30,31], and possible solutions [32]. While several of these methods are still at the research level, implementation in real-world EVs is a possibility that needs to be addressed by the research and development wing of the manufacturers.

1.3. EV Charging Levels, Connectors, and Standards

The charging levels are based on the power supplied, the source, and the charging time [25,33].

- Level-1 charging, also known as AC charging or residential charging, can supply up to 2 kW power from a 120 V, 16 A single-phase source;

- Level-2 charging, also known as AC split-phase charging, can supply up to 20 kW power from a 240 V, 80 A single-phase/split-phase source;

- Level-3 charging, also known as DC charging, can supply between 120 kW and 350 kW power from a variable DC source between voltages of 200 V and 920 V, at a maximum current of 500 A;

- Level-4 charging or Tesla Charging can supply 120 to 250 kW power from a 120 or 240, or 400 V source. This is applicable only for Tesla EVs.

A level-1 charger will require around 17–20 h to fully charge a battery with a 2 kW rating, while a level-2 charger will fully charge a 6.6 kW rated battery within 3.5 h. Level-3 and level-4 chargers are fast chargers that can charge high-power batteries in under 30 min [25,33]. The Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE) for EVs and plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) are governed by IEC 61851-1:2017 standards for the conductive charging system. For India, Bharat EV standards have been proposed by the Government of India to standardize EV charging in the country. Kumar et al. [34] have reviewed India’s EV charging station standards. The authors have presented the present scenario of EVs in India and the different charging levels with the connector specifications. The authors have also presented the details of the various existing international standards with their applications. Details of Indian Standards (IS) have been described in detail with the charging methodologies (CHArge de Move (CHAdeMO), Combined Charging System (CCS), and Tesla.). Based on the charging standard, the types of connectors have been standardized. The specifications of such charging connectors are listed below:

- AC Connector [25]

- Type-1: up to kW; follows SAE J1772 standard;

- Type-2: up to 43 kW for public charging; follows IEC 62196-2 standard.

- CHAdeMO [25,35]

- Present: 50 kW, 500 V/125 A rated high power charger;

- Proposed: over 100 kW, 500 V/200 A rated high power charger;

- ChaoJi (CHAdeMO 3.0): over 500 kW, 600 A rated high power charger for fast charging.

- CCS [25,36]

- Type-1: 90 kW, 600 V/150 A (maximum ratings); 13 kW, 250 V (nominal rating);

- Type-2: 170 kW, 850 V/200 A (maximum ratings); 44 kW, 230 V (single-phase)/ 440 V (three-phase) (nominal rating);

- Type-2 and DC connector Combination: 43 kW for AC charging and 100 kW for DC charging; can go up to 350 kW.

- Tesla Supercharger [25]

- 480 V fast charging technology.

The newer definitions/ratings of chargers are proposed to enable fast charging and are suitable for high-power vehicles.

2. Commercial EV Charger Specifications: Present Market Status

Several commercial organizations have their own patented EV charging stations with specific advantages and features for the benefit of the customers. Some companies have provided their charger specifications to help the public understand their charging system specifications to enable an informed choice. This section gives a list of some of the electrical specifications of the chargers.

2.1. Eaton Corporation

2.1.1. AC Charger-Eaton xChargeIn Mobility

The specifications of the Eaton AC Charger-Eaton xChargeIn Mobility are listed below [37].

- Power Range: kW to 22 kW;

- Connector Type: Type 1 for power levels up to kW, and Type 2 for power levels up to 22 kW;

- Input Voltage: 230 V, 50 Hz (1-phase) and 400 V 50 Hz (3-phase);

- Input Current: 16 A and 32 A for both 1-phase and 3-phase at respective power levels;

- Simultaneous Charging: No (only one vehicle can be charged at any given time).

2.1.2. DC Charger-Green Motion DC 22

The specifications of the DC Charger-Green Motion DC 22 are listed below [38].

- Power: 22 kW;

- Input Voltage: 400 V 50 Hz (3-phase);

- Power Factor: Greater than 0.99;

- Input Current: 32 A;

- Output Voltage Range: 50 to 500 V DC;

- Output Current: 55 A;

- Efficiency: Greater than 96%;

- Simultaneous Charging: No (only one vehicle can be charged at any given time).

2.1.3. DC Charger-Green Motion DC 44

The specifications of the Eaton DC Charger-Green Motion DC 44 are listed below [39].

- Power: 44 kW;

- Input Voltage: 400 V 50 Hz (3-phase);

- Power Factor: Greater than 0.99;

- Input Current: 64 A;

- Output Voltage Range: 50 to 500 V DC;

- Output Current: 110 A;

- Efficiency: Greater than 96%;

- Simultaneous Charging: No (only one vehicle can be charged at any given time).

2.1.4. DC Charger-Green Motion DC 66

The specifications of the Eaton DC Charger-Green Motion DC 66 are listed below [39].

- Power: 66 kW;

- Input Voltage: 400 V 50 Hz (3-phase);

- Power Factor: Greater than 0.99;

- Input Current: 96 A;

- Output Voltage Range: 50 to 500 V DC;

- Output Current: 165 A;

- Efficiency: Greater than 96%;

- Simultaneous Charging: No (only one vehicle can be charged at any given time).

2.2. Siemens

2.2.1. SICHARGE D for DC Fast Charging

The specifications of the Siemens SICHARGE D are listed below [40].

- Nominal AC Input Voltage: 400 V, 50/60 Hz;

- Nominal Input Current: 301 to 515 A, based on output power;

- Power Factor: Greater than at full load;

- DC Output Power: 160 to 300 kW;

- DC Output Voltage: 150 V to 1 kV.

2.2.2. VersiCharge for AC Charging

The specifications of the Siemens VersiCharge are listed below [41].

- Nominal AC Input Voltage: 230 V (1-phase), 230 or 400 V (3-phase); 50/60 Hz;

- Nominal Input Current: 10 to 32 A, based on output power;

- DC Output Power: up to kW (1-phase), up to 22 kW (3-phase);

- DC Output Current: 32 A maximum.

2.3. Need for Simultaneous Charging of EV Batteries

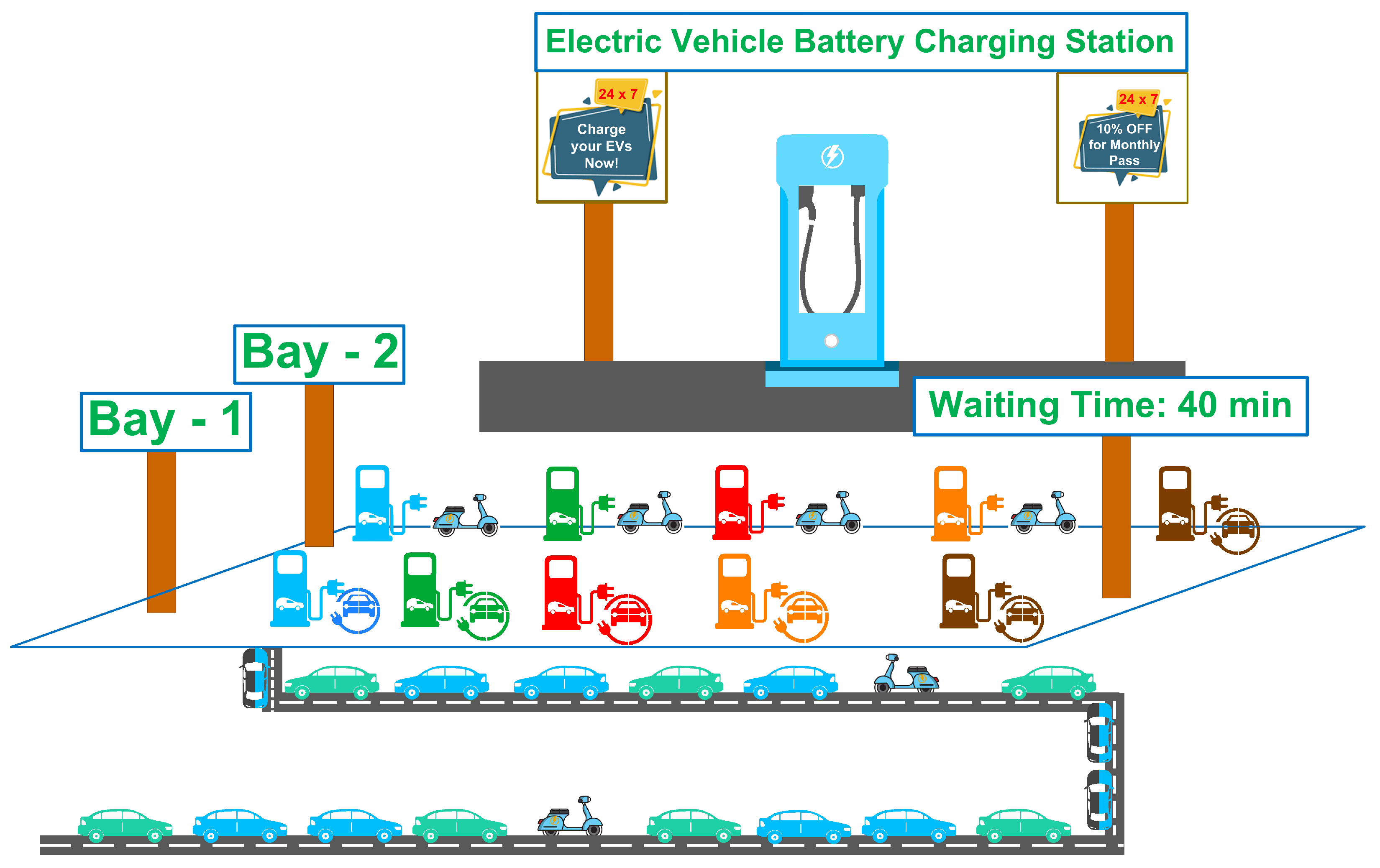

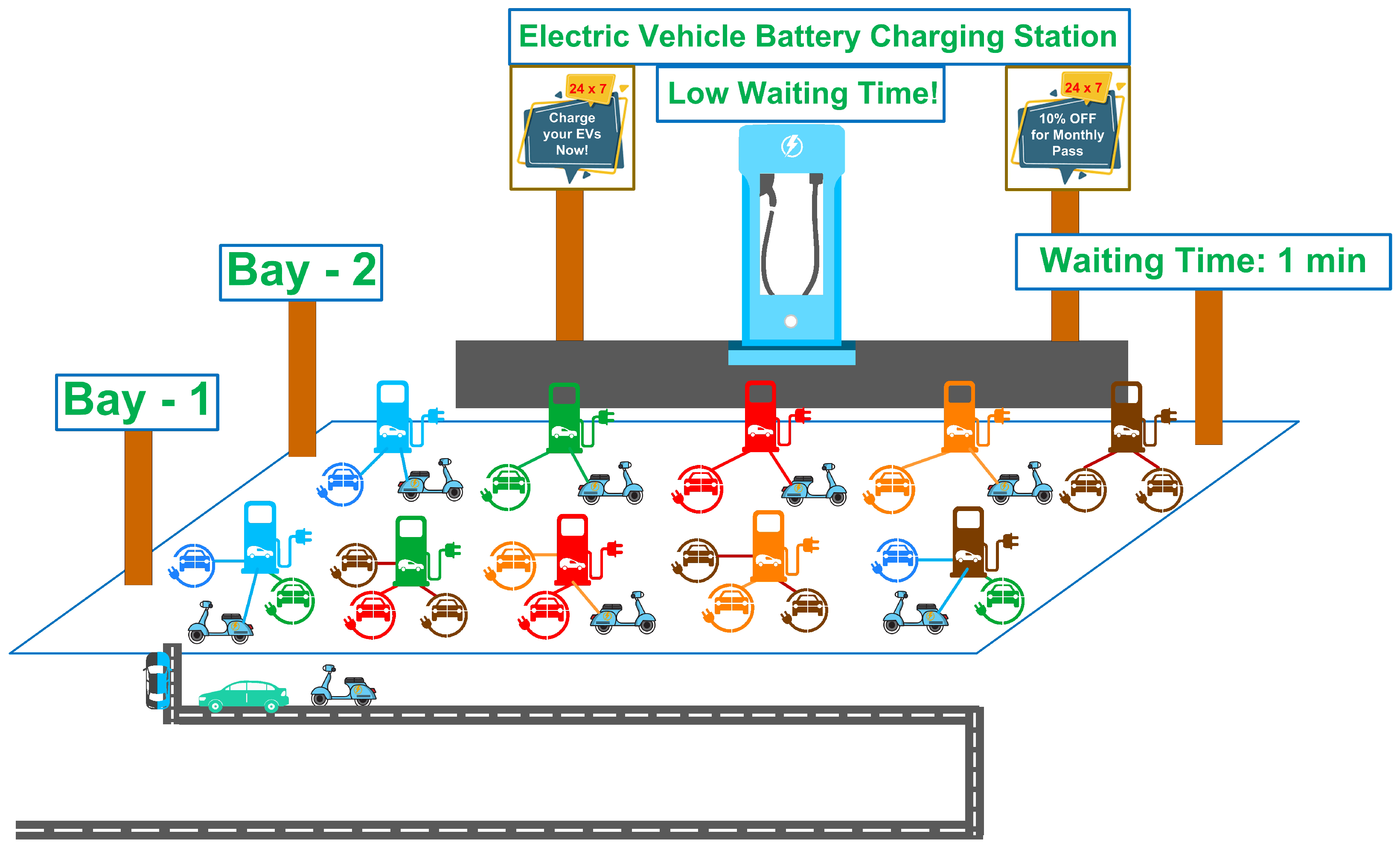

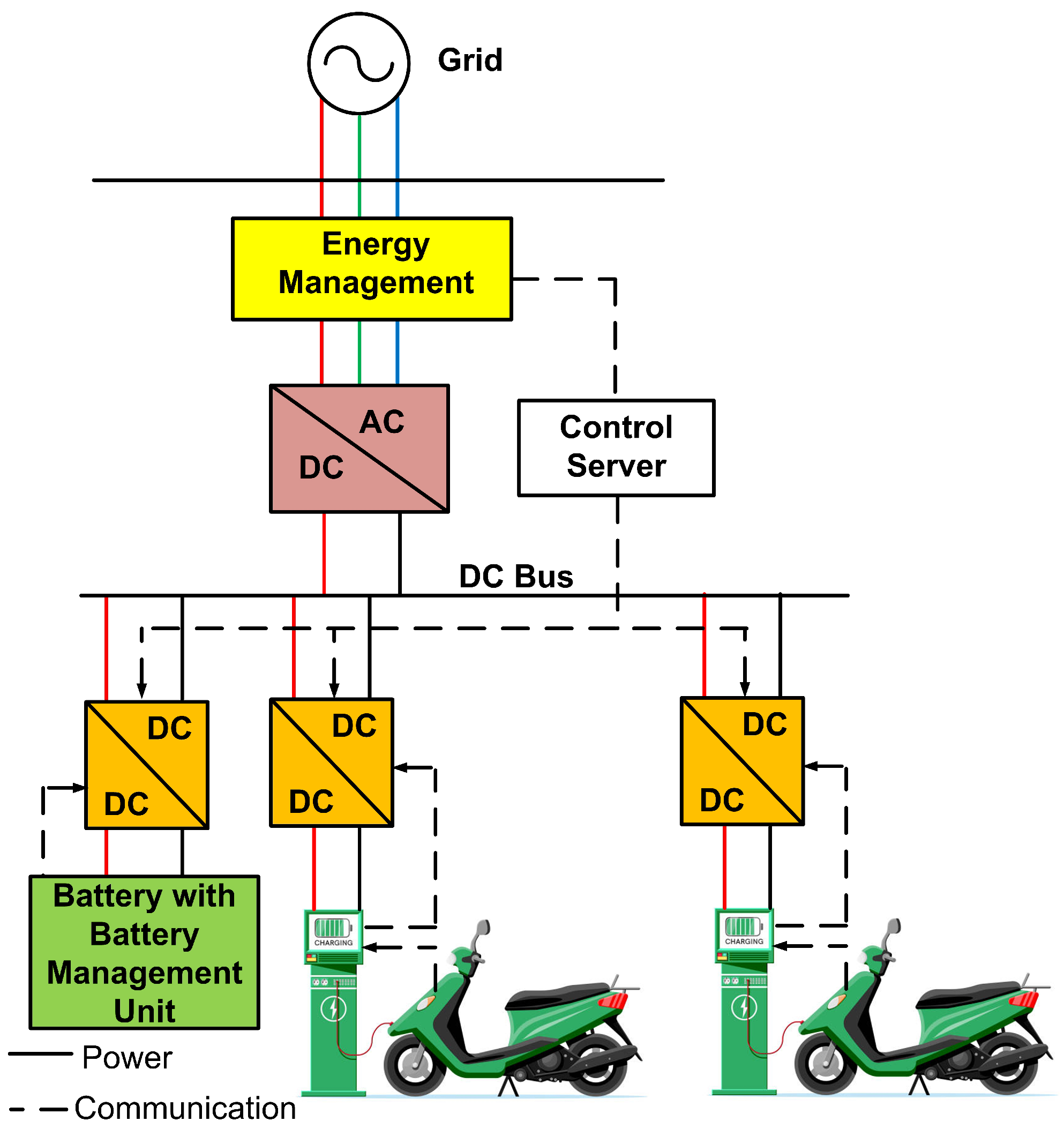

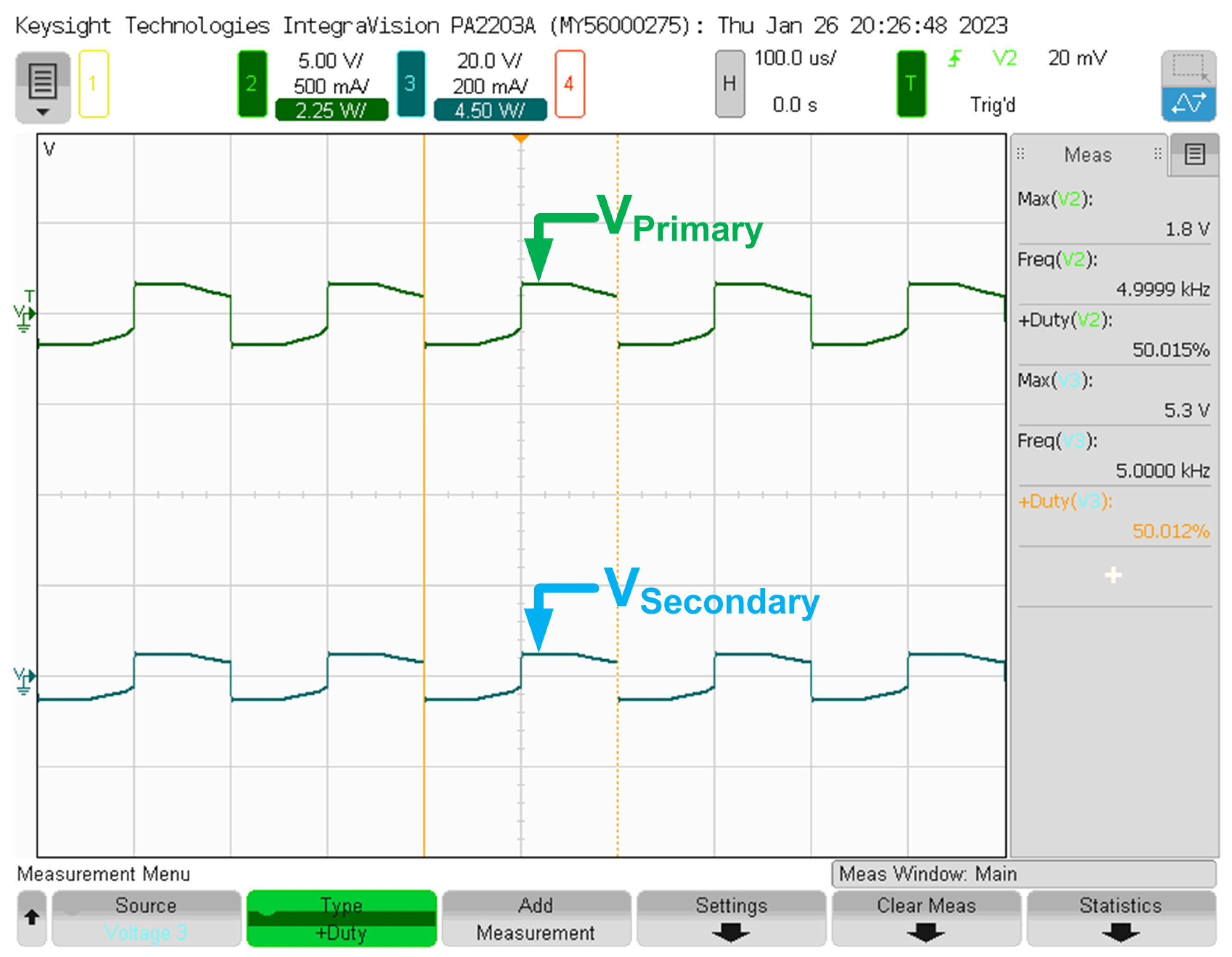

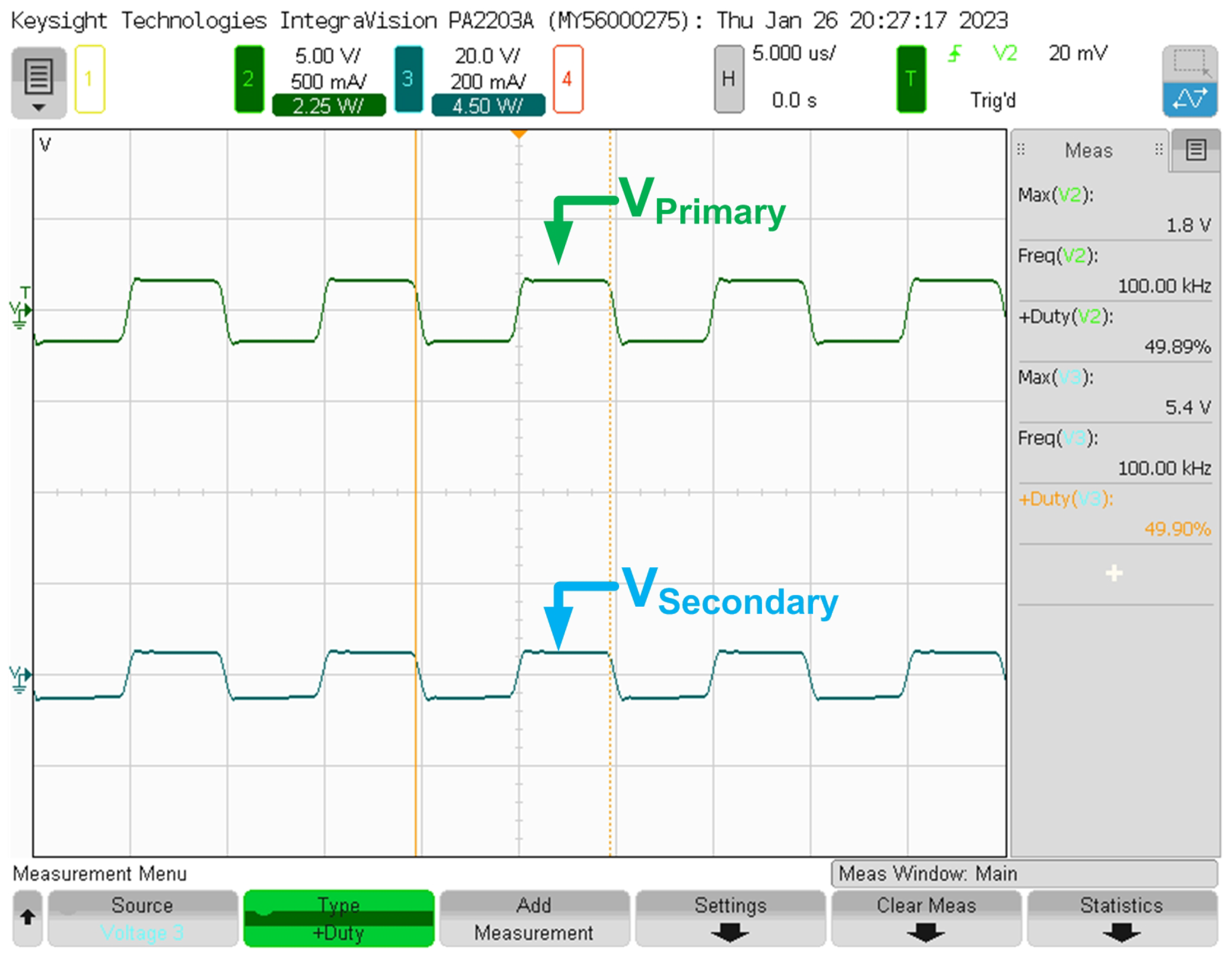

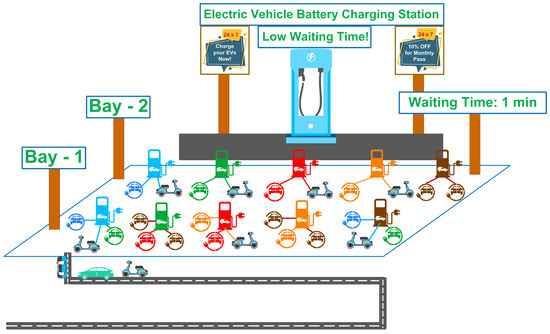

A significant issue that needs to be addressed is the reduction in waiting time before charging. One of the ways to reduce this is by installing more charging stations. While this process can reduce the waiting time before charging, installing more charging stations is related to other variables, such as land availability and acquisition and availability of power supply. Increasing the number of charging stations may not be a very simple or practical solution. In addition to optimizing the number of charging stations, it would be of great help if simultaneous charging of multiple EVs with the same or different rating batteries could be implemented. In a scenario where there are 10 chargers in a charging station, with each charger capable of charging 1 EV at a time, 10 EVs can be charged at any given time. This is shown in Figure 1. If it is possible to charge more than 1 battery (say, 2) in 1 charger, then the charging station described above can charge 20 EVs simultaneously. This creates a significant reduction in waiting time. This will directly create a positive impact on the conversion from ICEVs to EVs for mass-use. An added advantage will be obtained if multiple EVs of different ratings (say, an electric-bike and an electric-car) can simultaneously be charged by the same charger. This is shown in Figure 2. In addition to reducing waiting time, simultaneous charging also leads to higher profit for the company that installs and maintains the charging station since more vehicles can be charged in a given time-period, leading to an overall increase in the number of vehicles that are being charged each day. With this, we can conclude that simultaneously charging multiple batteries of the same and different ratings offers many advantages to customers and companies.

Figure 1.

Conventional EV charging station with one charger charging one EV battery.

Figure 2.

EV charging station with one charger charging multiple EV batteries.

Several authors have provided a detailed review of the various converters that can be used for EV battery charging. Khalid et al. [42] have reviewed the various isolated and non-isolated converter configurations that suit EV battery charging. In addition, the authors have provided the configuration of a charging station for fast charging, which includes the AC-DC multilevel converters. The concept of universal chargers has been described in work with various charging methods. However, the work does not deal with simultaneous charging and the corresponding modifications in the converters. In addition, the required design equations and loss calculation are beyond the scope of the review. Ghasemi-Marzbali et al. [43] have dealt explicitly with the infrastructure for fast charging of electric vehicles. The work gives details of the studies required for the charging station design, site selection and size determination, charging time estimation, and modeling of renewable energy resources for charging stations. The demand-side management principle has been introduced with risk factors and reliability considerations. The application of machine learning for system design has been described with a particular focus on fast charging stations. However, the work does not describe any converter topology required in the charger since the work’s objective is to review fast charging station requirements. Chakraborty et al. [44] have reviewed the various DC-DC converter topologies with a special focus on EV battery charging. Several isolated and non-isolated DC-DC converter topologies have been described in the work. Under the isolated converter topologies, full-bridge, current-fed converter, sinusoidal amplitude high voltage bus converter, and multi-input single output converters have been described. Design formulae for the memory elements have been provided for the described converters. The architecture of fast charging stations has been provided with a description of converters for the AC-DC and DC-DC conversion stages. In the DC-DC stage, full-bridge and phase-shifted full-bridge topologies for single-battery charging have been described. Common equations for loss estimation have been provided with the comparative efficiency for various switching frequencies. Various performance parameters have been compared for the described converters. However, the work does not describe loss estimation specific to the converters and does not include details for simultaneous charging. In addition, only some isolated converters have been described in previous work.

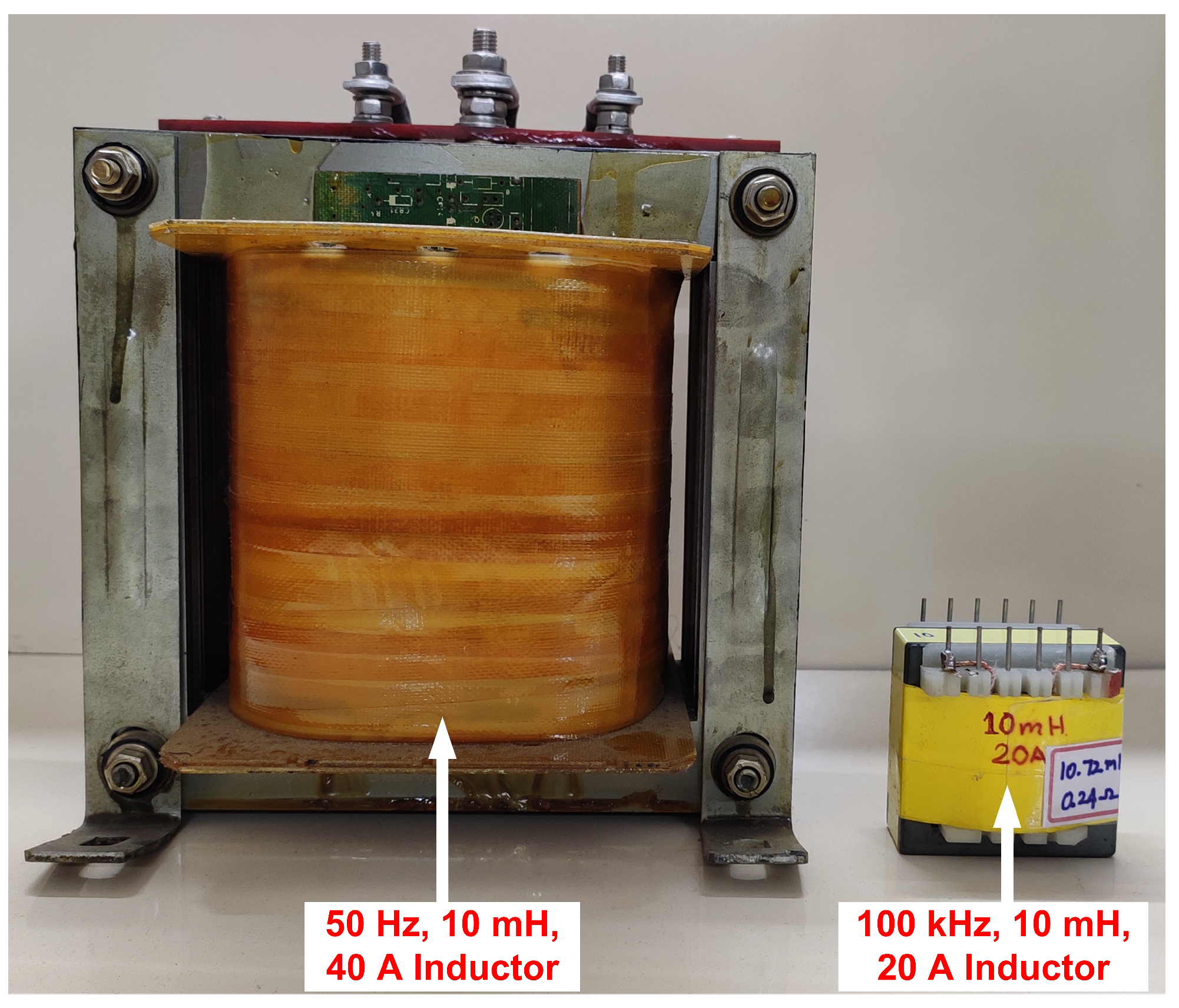

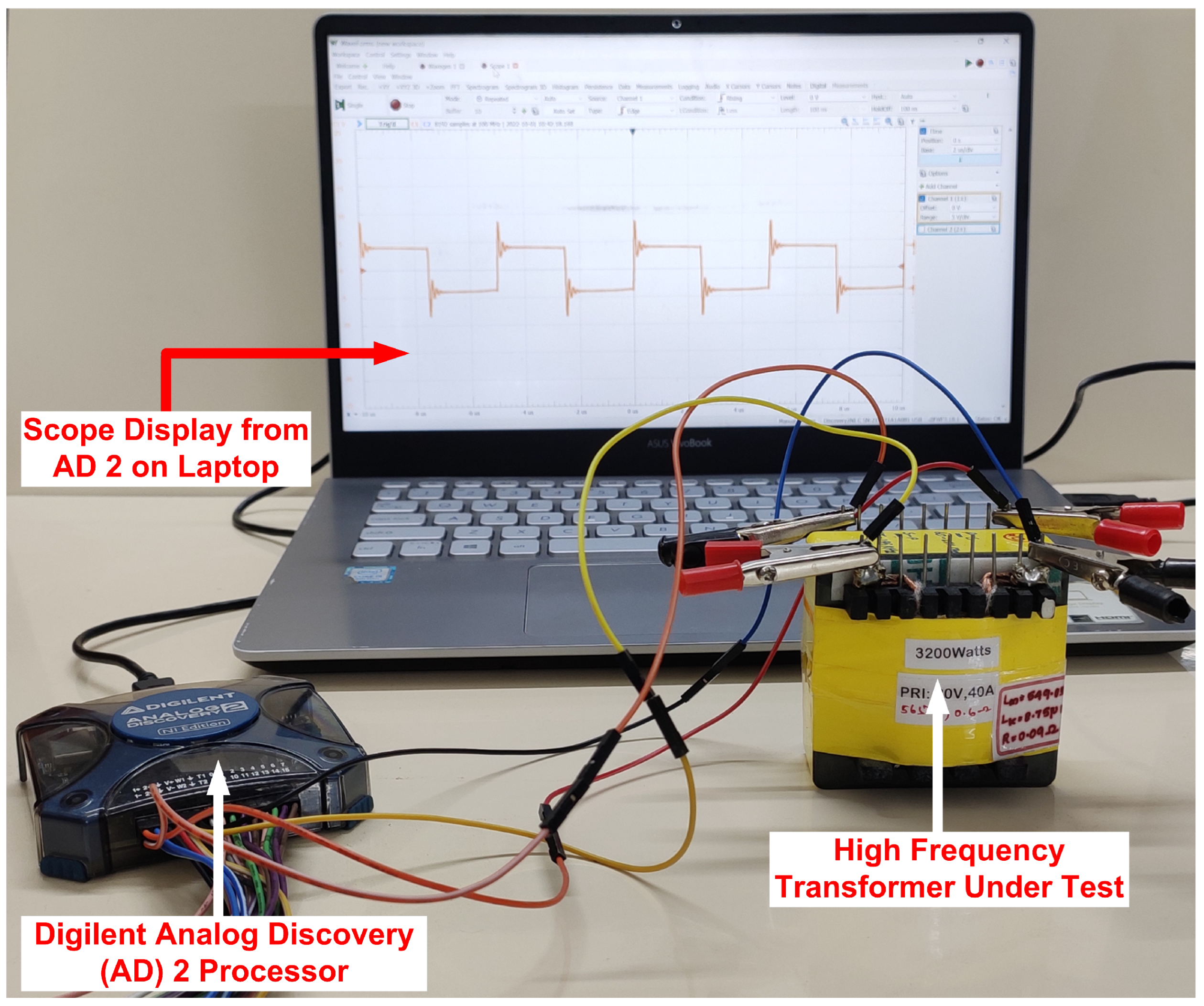

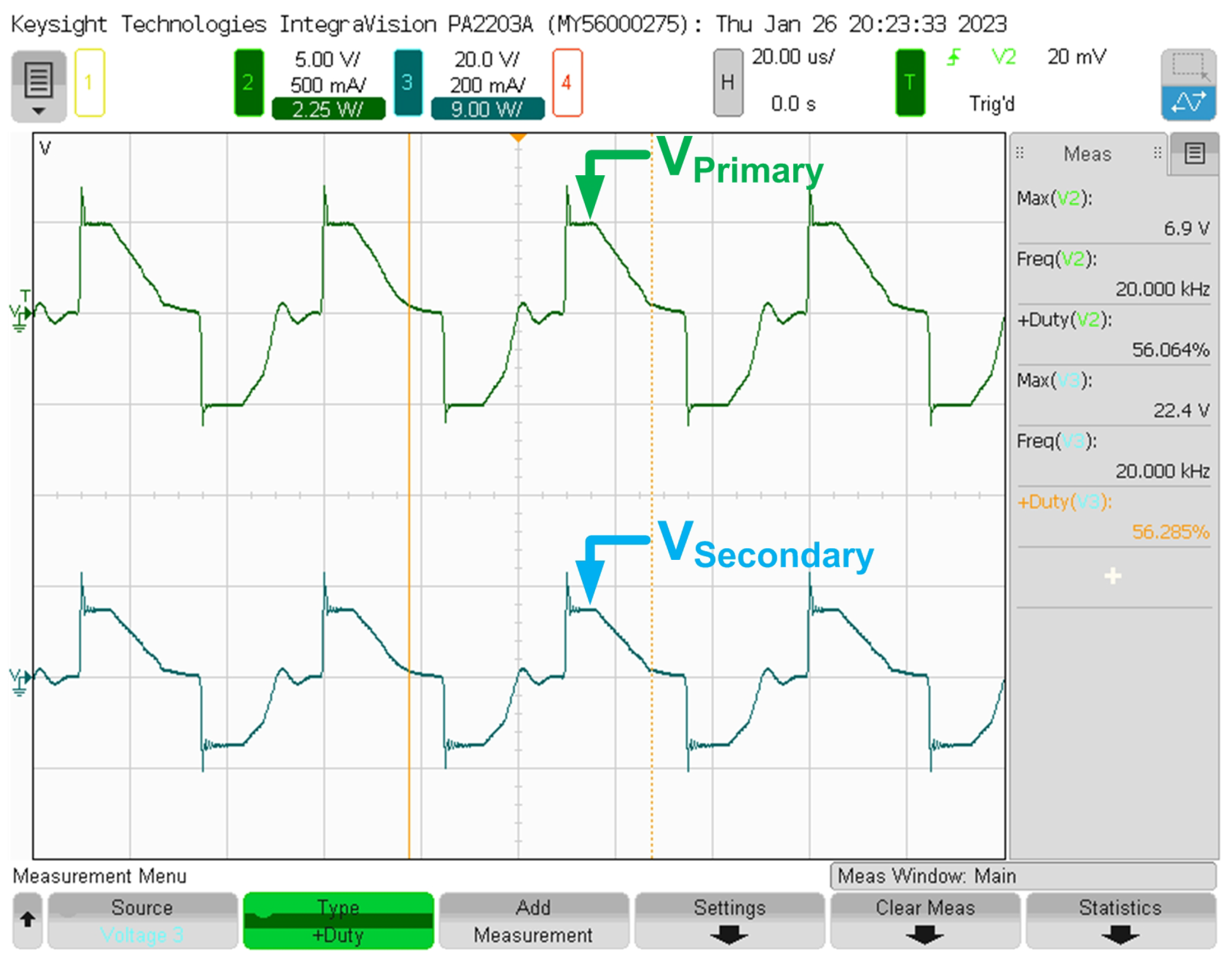

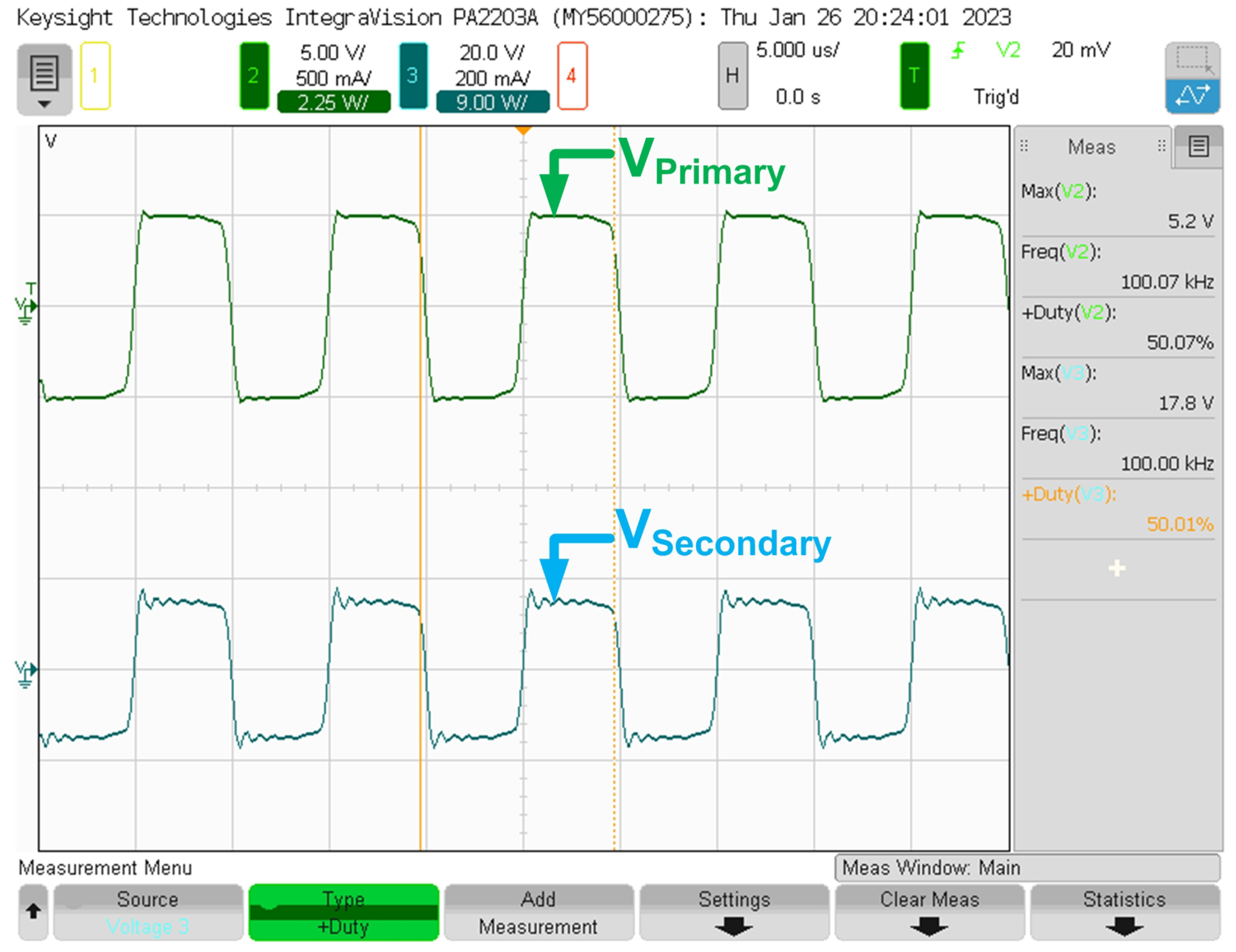

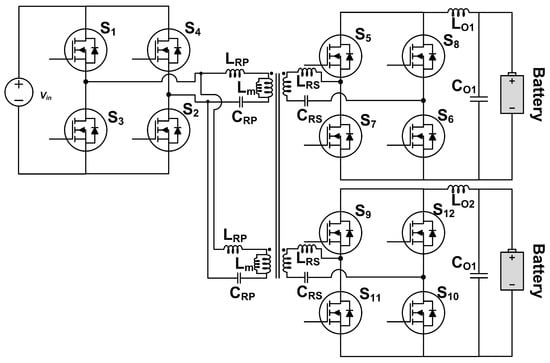

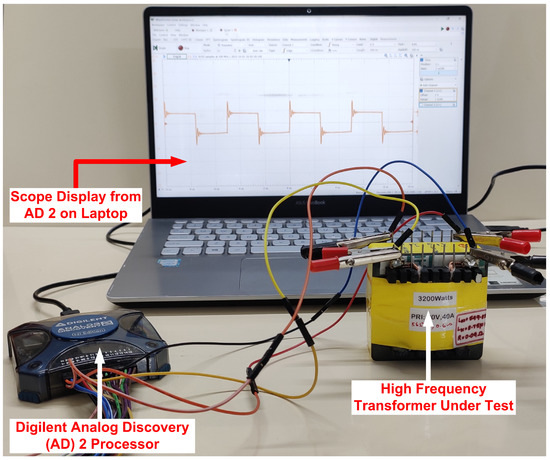

This work presents a detailed description of the various isolated converters that can simultaneously charge multiple EV batteries. While high-power converters such as full-bridge and its derived converters can be used to charge the battery of any vehicle, it is essential to note that a converter will give the desired performance only when it is operated at or close to the rated or designed conditions [45]. For example, a full-bridge converter-based charger designed for 10 kW can charge an electric car and an electric bike of low rating (say 250 W, such as the Hero Electric Flash electric bike used in India). However, not only will the converter be underutilized to deliver very low power for charging the electric bike, the cost per unit will be high when operated at low power [45]. To avoid this problem, isolated converters that can deliver low and medium-range power are very much needed when simultaneous charging infrastructure is planned since the same charger module should be able to charge vehicles with diverse power ratings. Thus, it is necessary to consider low and medium-power range isolated converters for EV battery charging applications, especially with simultaneous charging. This work also presents the detailed design and loss estimation process for various converters for low, medium, and high-power charging. In addition, a procedure for testing the high-frequency transformer (HFT) is provided, which has yet to be dealt with by previous literature.

This review work is organized as follows: Section 3 gives details of the main power quality issues that need to be addressed with battery charging. Section 4 details the various research works that have proposed and implemented simultaneous charging, with the advantages and limitations of each work. Section 5 explains the various isolated DC-DC converters that can be extended to charge multiple batteries simultaneously. The converters included in this section are the single-switch, two-switch isolated converters and bridge-type converters, including resonant converters, with their design equations and loss estimation. Section 6 gives a quantitative explanation of the multi-secondary HFTs required in the isolated converters for simultaneous charging with their testing procedure. Section 7 explains the trend of EV batteries shifting towards 400 V and 800 V levels. Section 8 describes the various products and projects that have implemented simultaneous charging features for public use. The paper concludes by describing the future research scope of simultaneous charging.

3. Power Quality Due to EV Charging: Concerns and Solutions

The supply systems in the world are invariably AC systems. This necessitates using an AC-DC converter in the battery-charging system. With grid connection, several important power quality parameters need to be considered. The power systems are usually designed keeping in mind the increase of load in the future. However, the sudden shift towards EVs has drastically increased the power demand, most likely more than the predicted demand. This has caused a negative impact on the grid and the system in general [46]. In addition, harmonics, low power factor, low voltage profile, and increased losses are causing significant trouble to the power system [46]. The power quality issues must be addressed more rigorously when multiple batteries are simultaneously charged. The power factor and the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) are the most important parameters that must be addressed. IEC61000-3-2 [47] governs the Power factor correction (PFC) or harmonic reduction. These parameters will be controlled using a feedback control system designed for PFC and harmonic minimization.

3.1. Power Factor Correction

PFC can be done using two [48] methods: (a) passive PFC and (b) active PFC. The passive method uses passive components such as inductors and capacitors to filter out the harmonics. The passive method is suitable for low-power applications (less than 100 W) since it leads to lower efficiency, high cost, and weight due to the size of line-frequency inductors and capacitors. On the other hand, active PFC methods use switching regulators to correct the wave shape to obtain sinusoidal grid current at unity power factor. This method is complex but is suited for high power levels. Active PFC can be done using converters that operate in continuous conduction mode (CCM), critical conduction mode (CrCM), and discontinuous conduction mode (DCM).

The general requirements of a PFC AC-DC converter topology include a simple power stage with a low number of components, less distortions in the input current, and the ability to achieve a near-unity power factor. Kolar et al. [49] and Friedli et al. [50] have provided an exhaustive review of the various topologies of PFC rectifiers. Conventional Boost PFC Rectifiers (CBRs) operating in CCM are among the most popular PFC topologies [51]. Integrated PFC controllers such as NCP1650 by ON Semiconductors [52] also work as a CBR. With Silicon Carbide (SiC) and Gallium Nitride (GaN) MOSFETs and diodes, the issue of output diode reverse recovery is mitigated [53]. The design of the memory elements of the CBR is the same as that of a conventional boost converter. In addition to the CBR, dual boost bridge-less PFC rectifiers [54,55,56,57,58,59], totem-pole bridge-less PFC rectifiers [60,61,62,63], and interleaved boost PFC rectifiers [64] are more commonly used [65] in several products that need PFC. On the three-phase system side, Vienna rectifiers have become very popular [66] since they have inherent PFC capability. Several control techniques can be used to achieve a unity power factor. Examples of control strategies include hysteresis control [67,68], average and peak current mode controls [69,70,71,72,73], model predictive control [74], sliding controller [75], and one-cycle control [76,77].

3.2. Harmonics and THD

EV battery charging systems are made of multiple power electronic converters and analog electronic systems. These are non-linear loads to the grid and hence cause harmonics in the grid current. The harmonics will be very significant when multiple vehicles are being charged at the same time [78]. Not only will the harmonic pollution of the grid current be higher in that part of the power system, but it will also reflect on all its connected systems and cause distortion in those parts. The presence of harmonics affects the operation of all the connected equipment and can also cause failures with considerable financial implications. EV charging can cause unbalance in the power system. Due to the unbalance, negative sequence components can be produced, producing a second-order harmonic ripple in the DC link voltage. This causes distortions in the grid input currents. Equation (1) can be used to explain the effects of harmonics [79] on the DC-link. The presence of even-order harmonics on the DC-grid side will cause the generation of odd-harmonics on the grid-side, leading to power quality issues. In Equation (1), represents the negative sequence components, and represents the DC current.

Other effects of harmonics on the various components of the power system are well known, and their solutions have been investigated for years. PFC converters are to be controlled such that the harmonics are mitigated well and the THD levels are within the permissible limits. In addition, strategic placement and optimal sizing of variable passive filters can also help in harmonic reduction. Alame et al. [80] have comprehensively analyzed the effects of harmonics due to EV charging on the various components of a distribution system. The authors have explained transformer loss modeling, temperature rise modeling, and lifetime modeling. A sample case study on a 1500 kVA distribution transformer has been provided to show that the percentage of harmonic currents increased with an increase in the battery state of charge. Further, the impact of EV charging on the distribution system has been analyzed by considering the IEEE 33-bus system charging four EVs at different buses using PV-based distributed generation units. The analysis has been performed using the decoupled harmonic power flow algorithm to obtain the effect on voltage quality and current THD. A centralized control flow has been proposed as an optimization problem to mitigate the effects of harmonics.

3.3. Other Detrimental Effects

Due to the diverse charging rates of EVs owing to slow, fast, and ultra-fast chargers, several negative effects can be observed. These include stability issues, unbalance, and overloading [79]. Dharmakeerthi et al. [81] have concluded that using fast charging stations can cause issues in the grid since they can significantly reduce the steady state voltage stability of the grid. In addition, the harmonics and inter-harmonics produced due to charging rates will also affect the power system’s critical components, such as transformers, breakers, cables, and meters. Alshareef and Morsi [82] have shown that fast charging stations can significantly affect and cause voltage flicker in distribution systems.

Despite these issues, EVs will be integral to our system since the advantages outweigh the limitations. Hence it is necessary to address these issues while designing a charging station. Nguyen et al. [78] have provided the topology of a photovoltaic inverter used as an active filter to mitigate power quality issues during simultaneous fast charging of five EV batteries. The proposed system models a bidirectional DC-DC converter acting as a charger and a DC-AC converter connected to the AC grid. Control structures for the control of both converters to implement harmonic mitigation have been explained, and the corresponding simulation results have been provided to validate the proposed scheme.

Once the AC power has been converted to DC and the power quality is maintained, a DC-DC converter is required to regulate the voltage, match the battery voltage level, and implement charging control. These DC-DC converters form a significant research area and are the focus of the following sections of this review, specific to the simultaneous charging of multiple batteries.

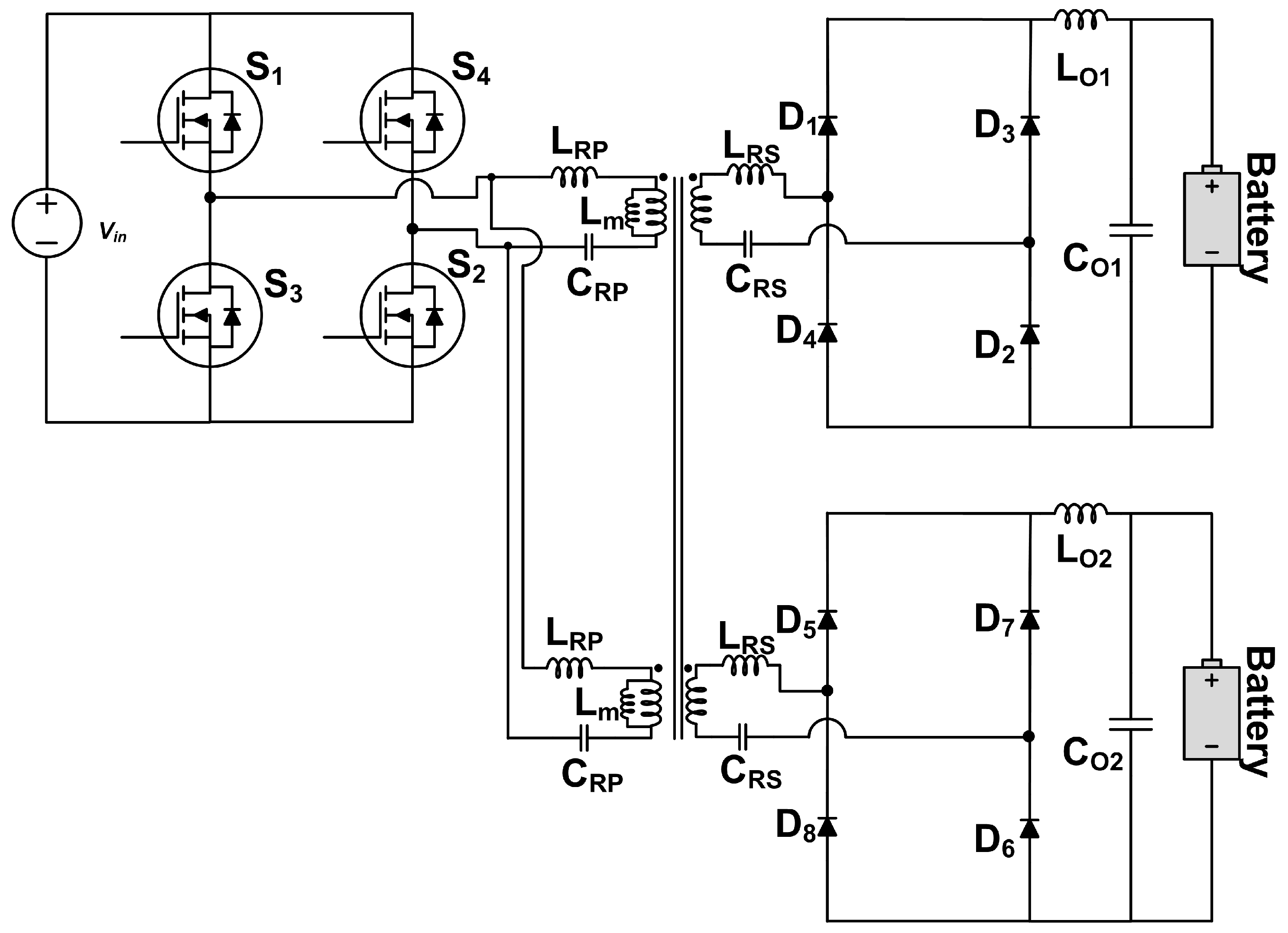

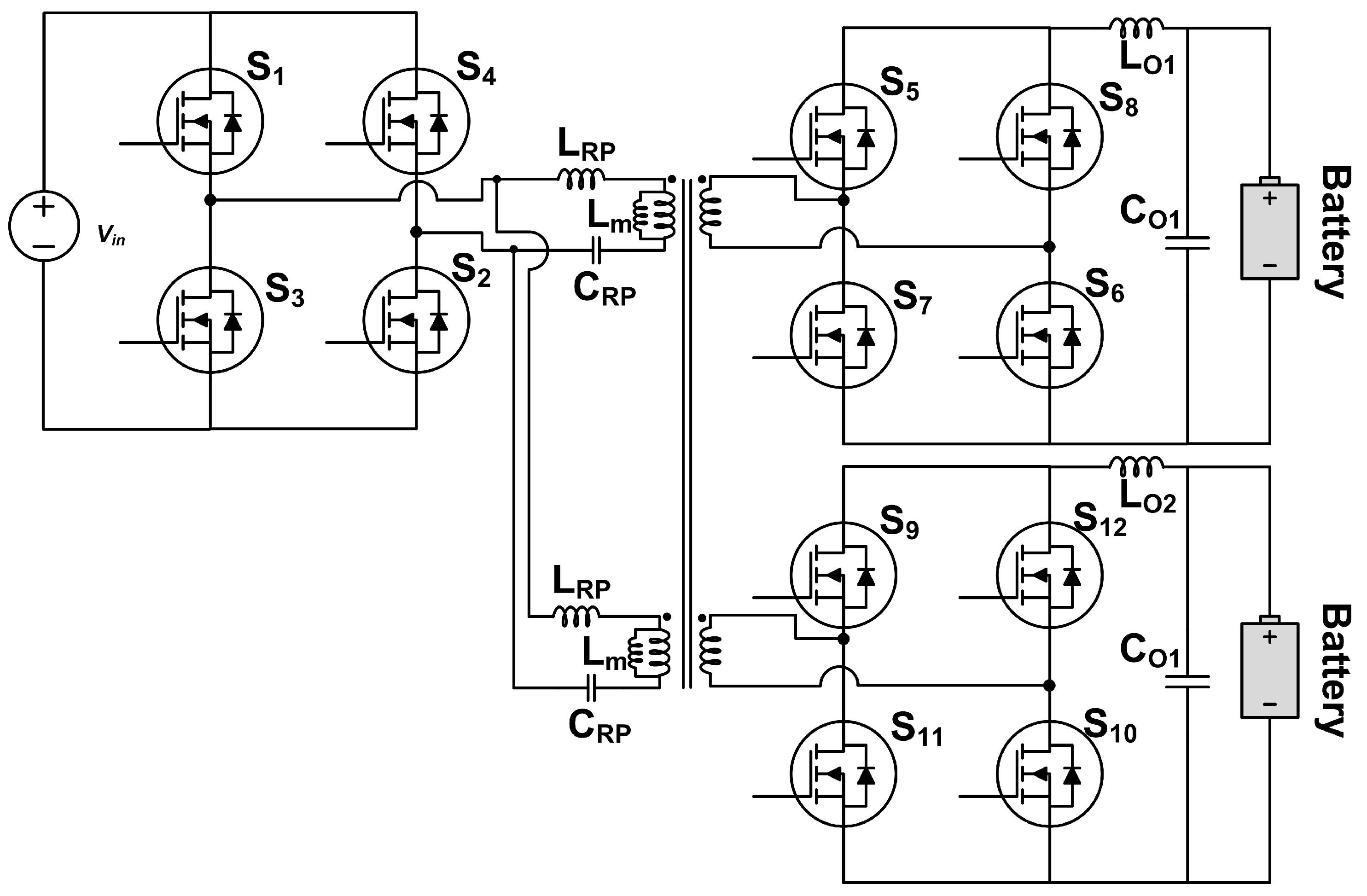

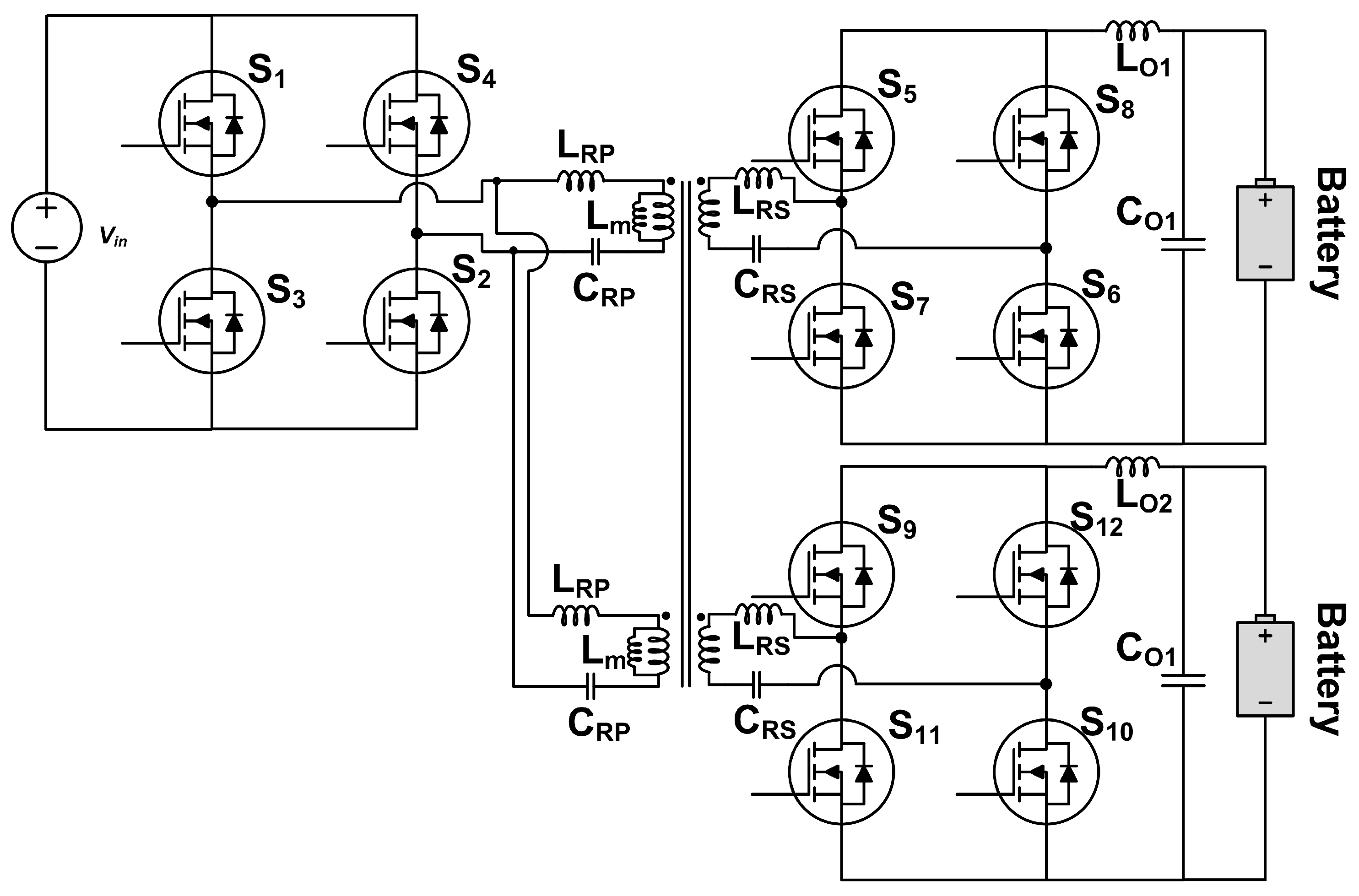

4. Simultaneous Charging Research: State of the Art

Only a few researchers have taken up experimental validation of simultaneous charging of EV batteries. Although it leads to the many advantages described in Section 2.3, the research focus has been relatively less compared to the focus on fast charging for charging time reduction. This section describes the various converters proposed by researchers working on simultaneously charging multiple batteries.

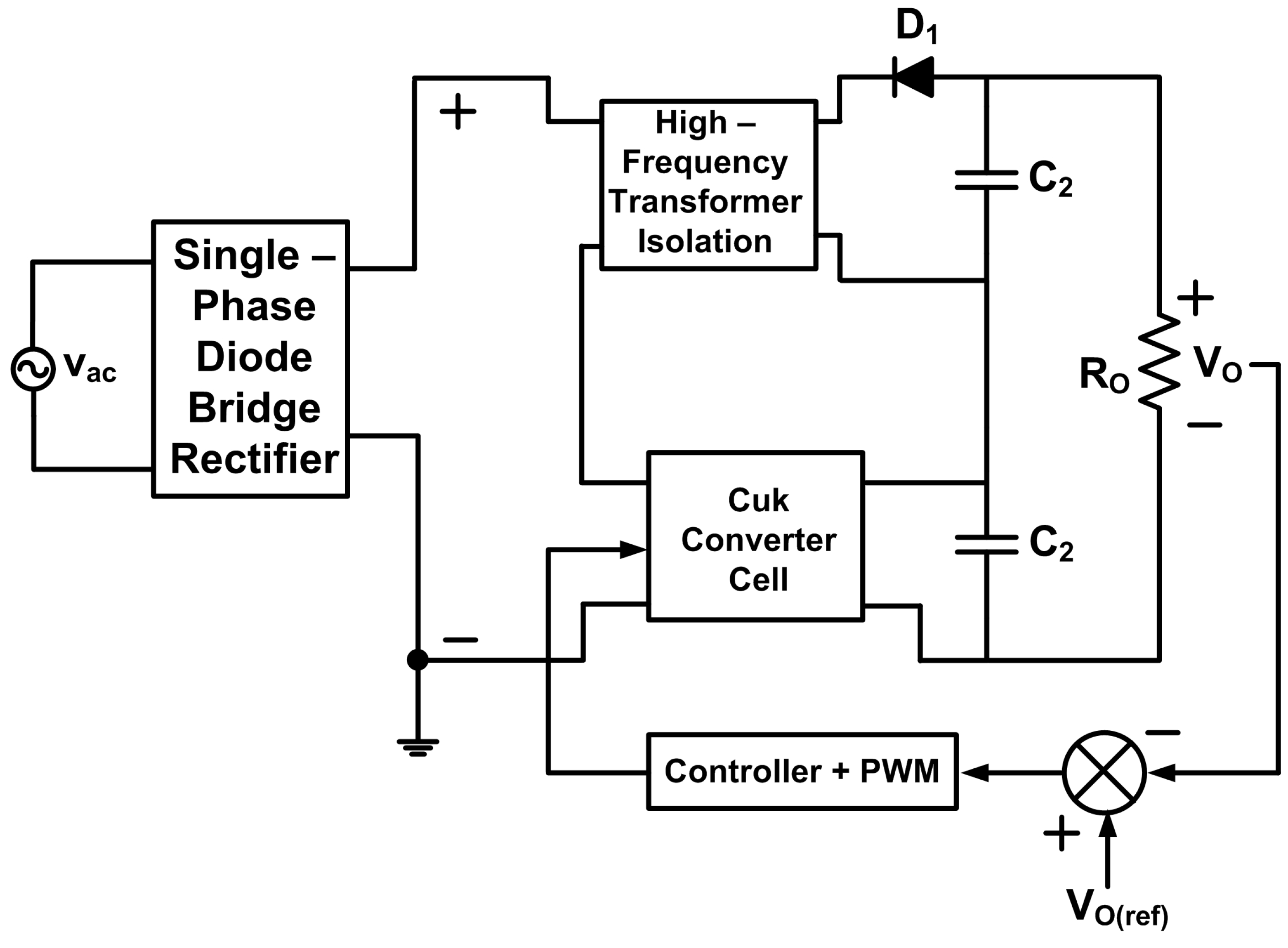

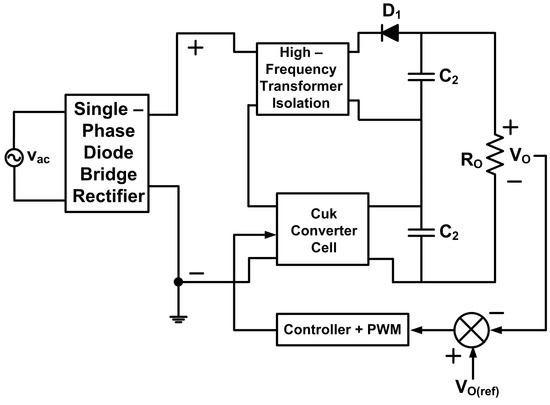

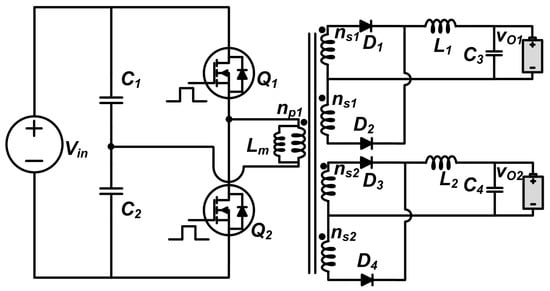

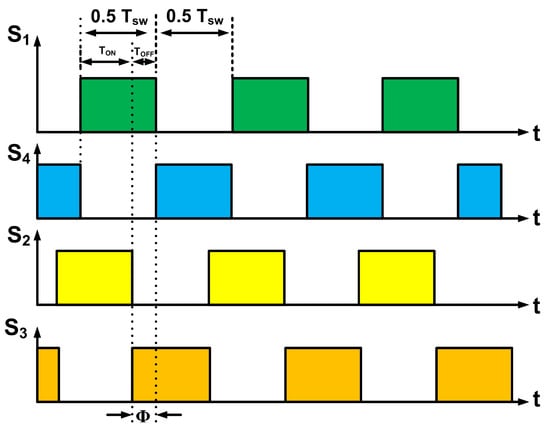

Mahafzah et al. [83] have proposed a synchronized multi-output hybrid buck-boost converter based on the Ćuk-Flyback topologies for renewable energy systems and electric vehicle applications. The proposed converter is shown in Figure 3. The design and steady-state analysis are provided for the proposed converter. The authors have presented the simulation results for a 300 W design to obtain a full-load efficiency of 90% at higher duty cycles close to . This is significantly higher than the conventional Flyback and Ćuk converters. For EV battery charging applications, the authors have proposed an AC-DC full-bridge PFC rectifier connected to the input terminals of the proposed converter. A simulation of a kW system is provided to validate the idea. With the proposed AC-fed system, a power factor of is obtained at the AC input side for an input of 200 V and for an AC input of 110 V. At these two input voltage levels, the THD is 27.69% and 36.25%, respectively. The work provides a novel multi-output converter fed from a single source. However, the converter is mainly suited for low-power EV charging at lower output voltage levels (such as a 48 V Li-ion battery).

Figure 3.

Converter proposed in Ref. [83] for EV applications.

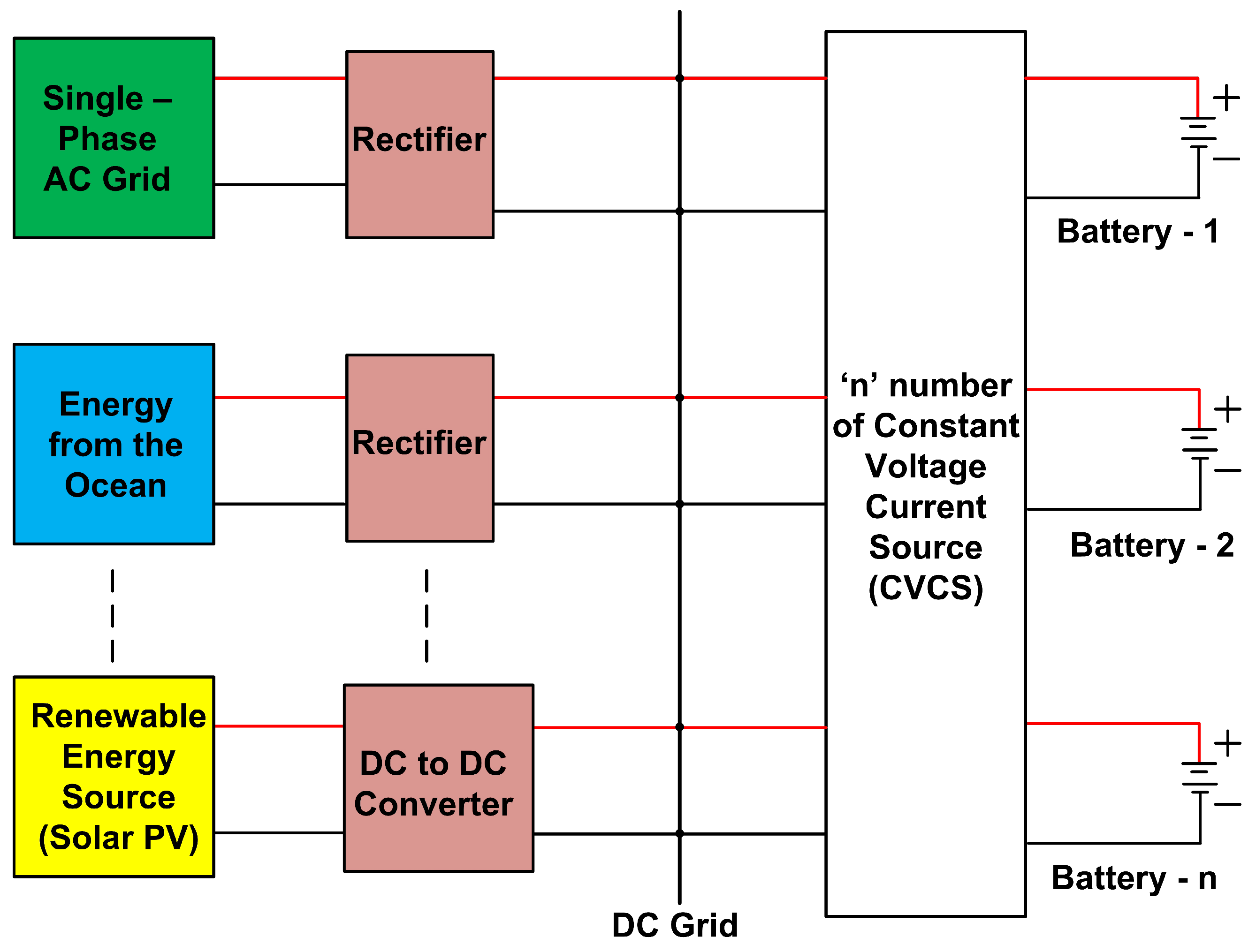

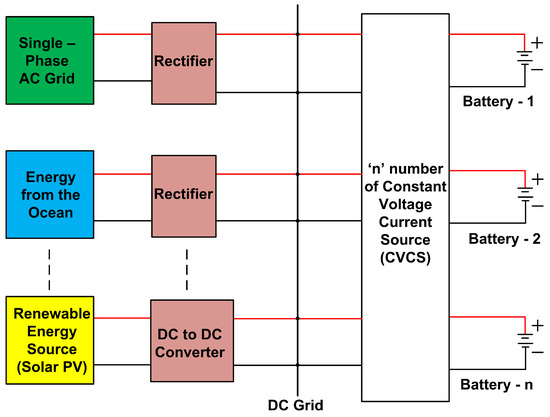

Chen et al. [84] have considered the case of simultaneous charging as a constrained optimization problem to minimize simultaneous charging time. The block diagram of the solution proposed by the authors is shown in Figure 4. The authors have considered four objectives: convergence of State-Of-Charge (SOC) deviation, minimization of loss due to internal resistance, equating the SOCs of different batteries, and minimization of simultaneous charging time. The constraints are the SOC limitation of the batteries, the limitation on charging current, and the terminal voltage of the batteries. The authors have provided the battery pack model and developed the optimal charging strategy where trade-offs are made between the objective functions since it is impossible to optimize all objectives simultaneously to obtain a single solution to such problems. To tackle this problem, the authors have used the Adaptive Momentum-Based Steepest Descent (AMSD) algorithm and performed a simulation on the PLECS software platform with four battery packs and four Constant Voltage Current Sources (CVCS). For simulation, Ah batteries have been considered, and the rating of the CVCS is 5 V. The simulation results have shown that the equilibrium time is reduced by more than compared to the quasi-sliding mode control. In addition, the convergence of the charging error is shown to be faster with the proposed algorithm. Experimental validation of the proposed method is provided by charging NCR 18650 Ah lithium-ion batteries (considered equivalent to battery packs). The experimental results have been used to show the superiority of the proposed algorithm over the battery-assisted charging system. The simultaneous charging time was observed to be minimum with the proposed algorithm, and the proposed system is said to prevent the over-charge and over-discharge of the battery. The work deals with simultaneous charging as an optimization problem focusing on reducing simultaneous charging time. However, the proposed system will have an increased component count for high-power EV battery charging applications, which may lead to lower reliability. If a diode rectifier is used for AC to DC conversion, there will be no control over the DC link side voltage when the input voltage changes. If a fully controlled rectifier is employed, the control becomes complex. With a full-bridge or its derived DC-DC converters, higher output voltage and power can be obtained, and it will be suitable for higher voltage battery charging, which will also involve reduced current, thereby reducing the losses in the secondary. Since the DC-DC converters can be designed based on the requirement of the charging station, the architecture proposed by the authors is very well suited for the simultaneous charging of vehicles with batteries of different voltage and power levels.

Figure 4.

Block diagram proposed in Ref. [84] for simultaneous battery charging.

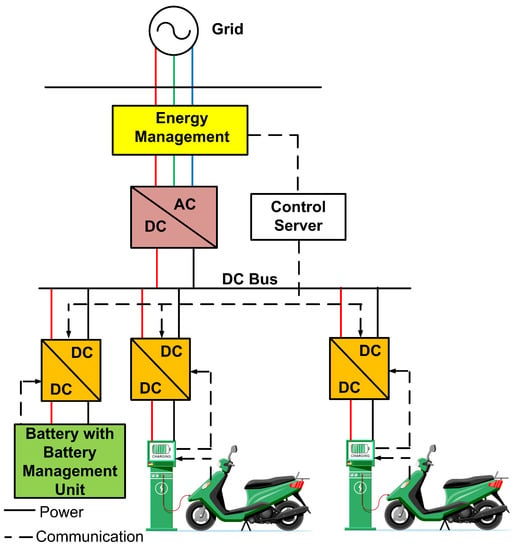

Aziz and Oda [13,85] have evaluated a battery-assisted quick-charging strategy for the simultaneous charging of EVs to reduce the burden on the grid. The proposed system is represented in Figure 5. The control server is considered to control the energy flow into all the parts of the community considering the related economics. The authors have considered the CHAdeMO standard for testing the charging of the quick chargers and the Li-ion battery for different seasonal conditions. A 50 kW inverter with an input voltage of 450 V and output RMS voltage of 200 V is considered, with the DC-DC converter feeding a 400 V battery with a maximum current of 150 A. The kWh battery with a nominal voltage of V and a maximum charging voltage of V is considered. The 50 kW chargers are taken to have a variable DC output voltage of 50 to 500 V and a maximum output current of 125 A. The authors have concluded that the proposed battery-assisted system facilitates an increased charging rate and shorter charging time compared with the conventional system without battery support. This work describes the system for battery charging, and can be used for charging batteries at higher power and voltage. Better control is possible for the AC-DC and DC-DC converters to regulate the DC bus voltage and the charger output voltage. With full-bridge or dual active bridge (DAB) converter variants, higher power and voltage charging can be achieved at high efficiency. However, lower reliability could affect the system, and the control will be relatively complex.

Figure 5.

Simultaneous charging scheme proposed in Ref. [13].

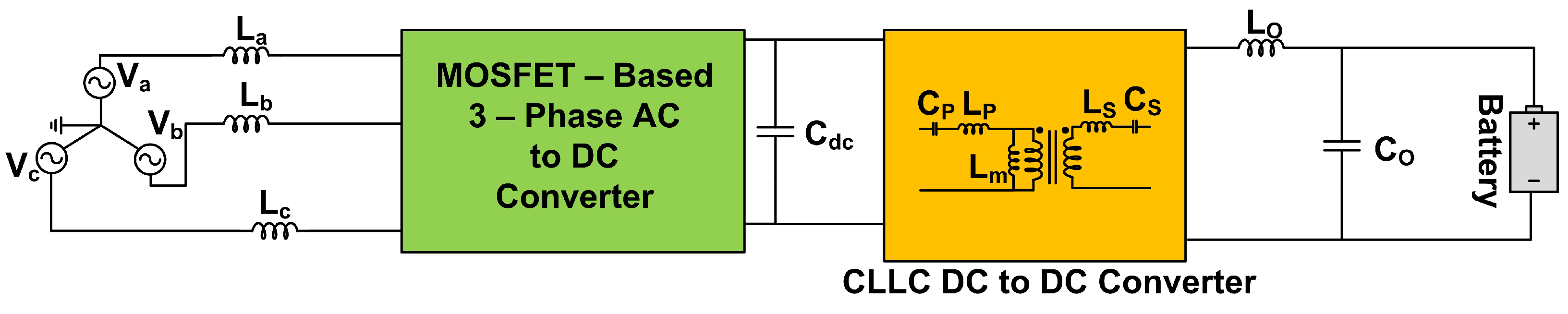

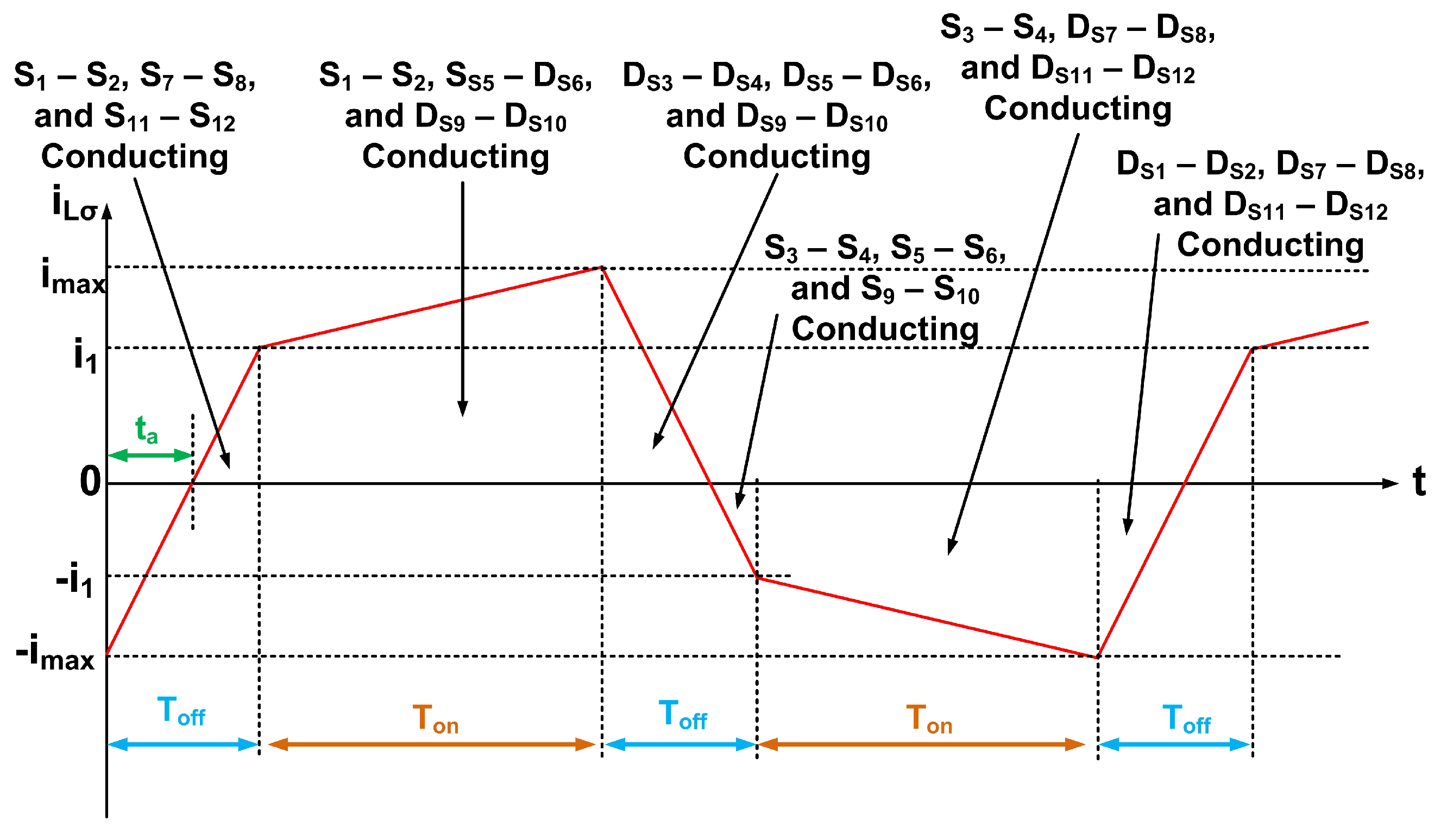

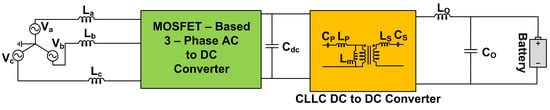

Okon et al. [86] have described a CLLC-based charging circuit, shown in Figure 6, to charge a Li-ion battery using the CC-CV charging method. The operation is done in two stages, with the first stage providing control signals in progression and the second stage controlling the battery’s CC-CV charging. The authors have suggested creating a DC bus to connect multiple converters in parallel to enable multiple-battery charging. The authors have proposed a modified combined control system to control the proposed converter. The authors have provided simulation results obtained from PLECS software to validate the single battery charging. The authors have claimed that the system can be used for multiple-battery charging using the DC bus described above. Practical implementation has not been provided in this work for simultaneous battery charging. The proposed system is very well suited for high-power, high-efficiency battery charging, even with batteries with voltages greater than 400 V. On the other hand, the implementation of simultaneous battery charging will need a higher component count, thereby leading to an increase in the size and weight of the system.

Figure 6.

Converter proposed in Ref. [86] for battery charging.

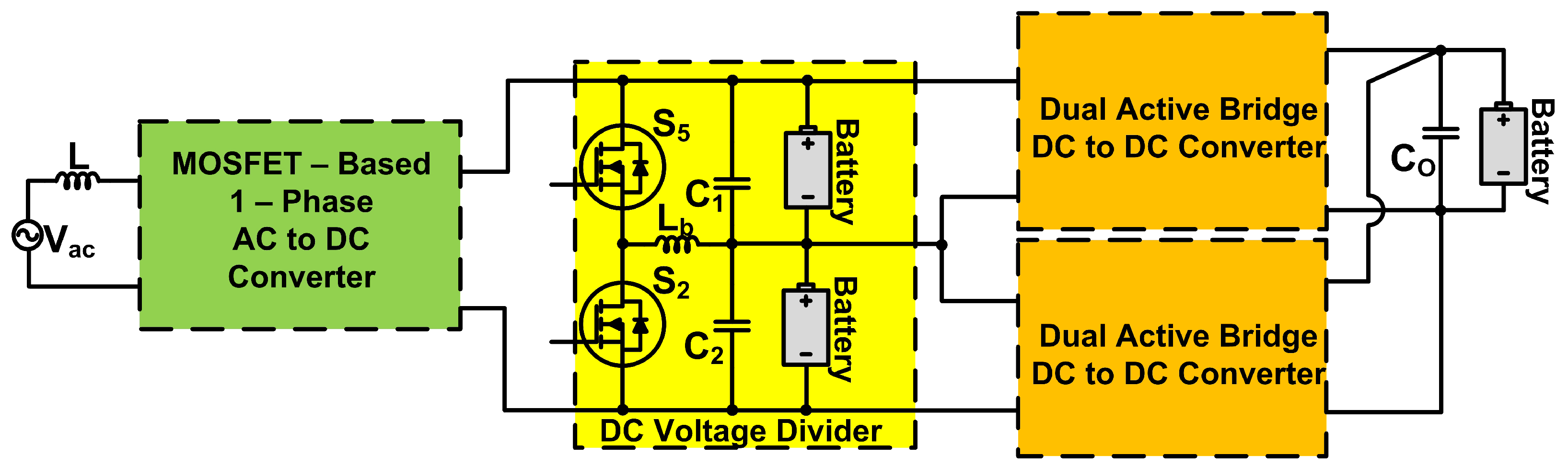

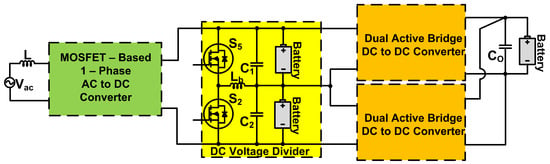

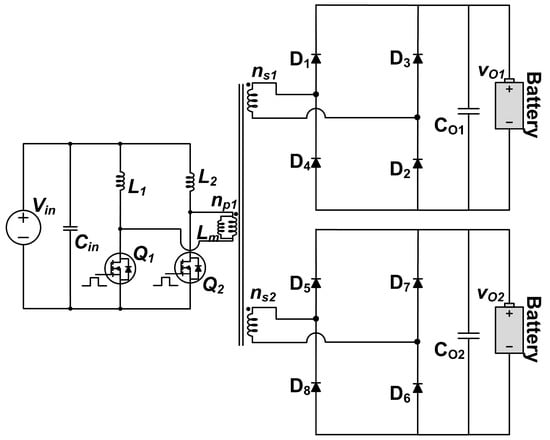

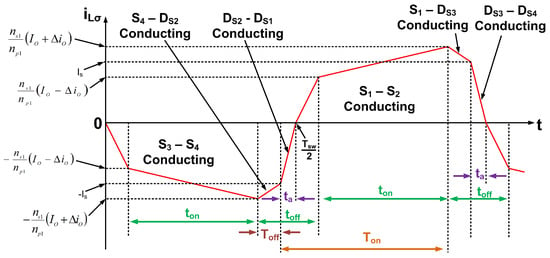

Li et al. [87] have used two dual active bridge (DAB) converters with a rectifier and DC voltage divider to charge three Li-ion batteries, as shown in Figure 7. The proposed converter is a two-stage circuit. It uses a single-phase AC-DC converter, a DC voltage divider (using split capacitors with a neutral inductor and half-bridge configuration), and two parallel DAB converters. Two batteries are connected across the two split capacitors, and the DAB converter feeds the third battery. Correspondingly, control strategies are provided for the rectifier, the neutral leg circuit, and the two DAB converters. The rectifier is controlled using a double loop controller with a PI controller and a PR controller to obtain a constant DC voltage at the common node of the capacitors C1 and C2. The neutral leg is controlled using another double-loop controller with two PI controllers. The DAB converters are controlled using the concept of phase shift and feedback compensation. The circuit is fed from a 400 V, 50 Hz grid to obtain a DC link voltage of 560 V. A resistive load of 60 Ω is used instead of a battery for testing. Simulation and test results have been provided to validate the proposed system, considering a switching frequency of 4 kHz. The topologies proposed in work are well suited for high-power, high-voltage battery charging. The trade-off is with the higher number of components. The control is very flexible, specifically with DC-link voltage control. The two batteries that feed at the output terminals of the DC voltage divider have a common node. It would be preferable to isolate these two batteries to prevent current flow from one battery to the other.

Figure 7.

Converter proposed in Ref. [87] for multiple battery charging.

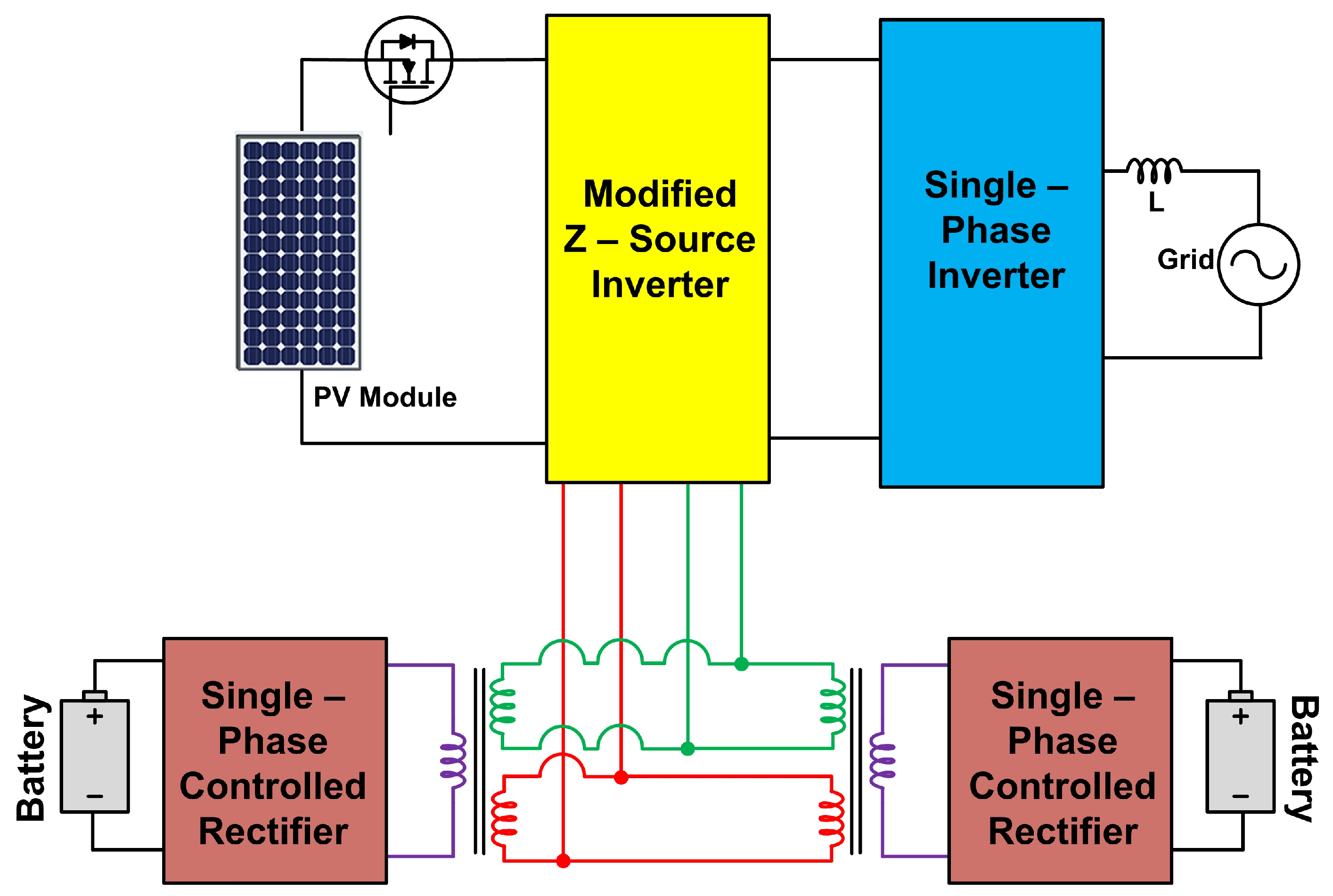

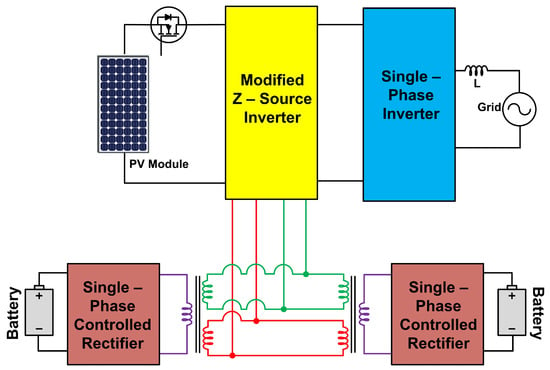

Ramanathan et al. [88] have proposed a PV- and grid-fed modified impedance source inverter (ZSI) with transformers and full bridge rectifiers to charge two batteries simultaneously. The block diagram of the proposed circuit is shown in Figure 8. The maximum shoot-through duty ratio of the ZSI is calculated. Then the inductor and capacitor values are obtained. The system is configured to operate in four modes. Power flows from the PV to the grid in the first mode. The PV system charges the battery via the HFT in the second mode. In the third mode, the battery transfers energy to the grid through the inverter; in the fourth mode, the grid is used to charge the battery. The authors have considered the switching frequency of 20 kHz for the ZSI and 40 kHz for the half-bridge converter. A battery power of 200 W is considered. The authors have provided the simulation results from MATLAB/Simulink to show the simultaneous charging of the two equal-rated batteries. The system can be used up to a medium power level since it is fed from a single-phase supply. With the use of controlled rectifiers as proposed by the authors, it is possible to control the battery charging current for each battery. The system is not well suited for higher voltage batteries.

Figure 8.

Converter proposed in Ref. [88] for multiple battery charging.

Graw and Zimmermann [89] have proposed a boost-flyback converter combination to charge battery stacks separately from a renewable energy source. The work aims to simultaneously charge both a high voltage (HV) battery and a low voltage battery from a single source. The authors have explained the modes of operation of the proposed converter with the corresponding timing diagrams and the design of the flyback transformer. Overcharging the LV battery is prevented by redirecting the power to the HV battery, leading to simpler control. The effect of the capacitance between the adjacent transformer windings has been evaluated, and the effect on efficiency is noted. The authors have also considered the effect of adding an LC snubber as a method to reduce the MOSFET drain peak voltage. The proposed system is a combination of an isolated and a non-isolated converter. It can be used only for power levels below 100 W and is unsuitable for fast charging. The system has common ground between the secondary and primary due to the combination of the non-isolated and isolated converters. The circulating current from the HV battery to the LV battery is possible due to this. It could also lead to EMI issues when etched on a PCB.

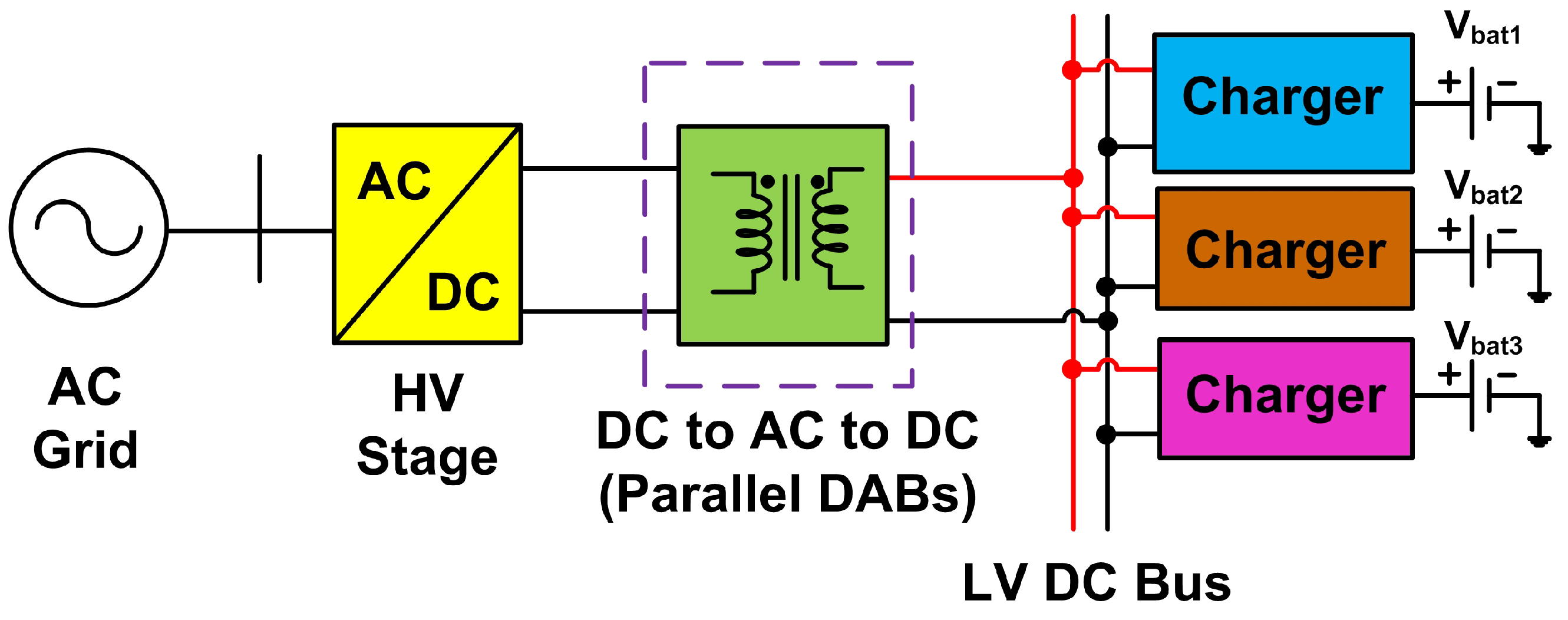

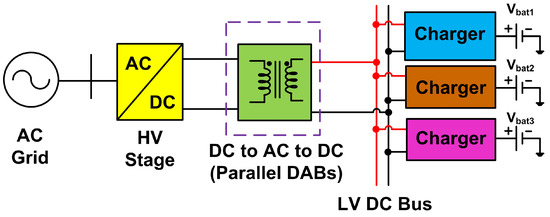

Sun et al. [90] have proposed an isolated multi-port DC charging station as a part of a smart grid system. The block diagram proposed by the authors is shown in Figure 9. The HV stage employs a cascaded H-bridge converter, and the isolation stage uses multiple cascaded DAB converters. The DC side of all the DABs is connected to the DC bus, which charges multiple batteries simultaneously using separate chargers. Dual-loop control is used for the rectifier stage, while the voltage control strategy with a current balancing function controls the DAB stage. Both Grid-to-Vehicle (G2V) and Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) are employed in the charging module. The authors have provided the simulation results for the proposed system. The simulation system comprises 24 rectifier modules, each connected in series with a DAB operating at a switching frequency of 10 kHz. The three batteries are at voltage levels of 300 V with capacities of 15 kWh, 15 kWh, and 20 kWh, with different SOCs. The objective of the work is to validate the proposed topology, which has been done using simulation. The hardware implementation of the proposed system has not been provided in the work. The system is very well suited for high voltage batteries as described by the authors. However, the intermediate conversion stage has a very high number of devices, which may lead to poor reliability in real-time implementation.

Figure 9.

System proposed in Ref. [90] for multiple battery charging.

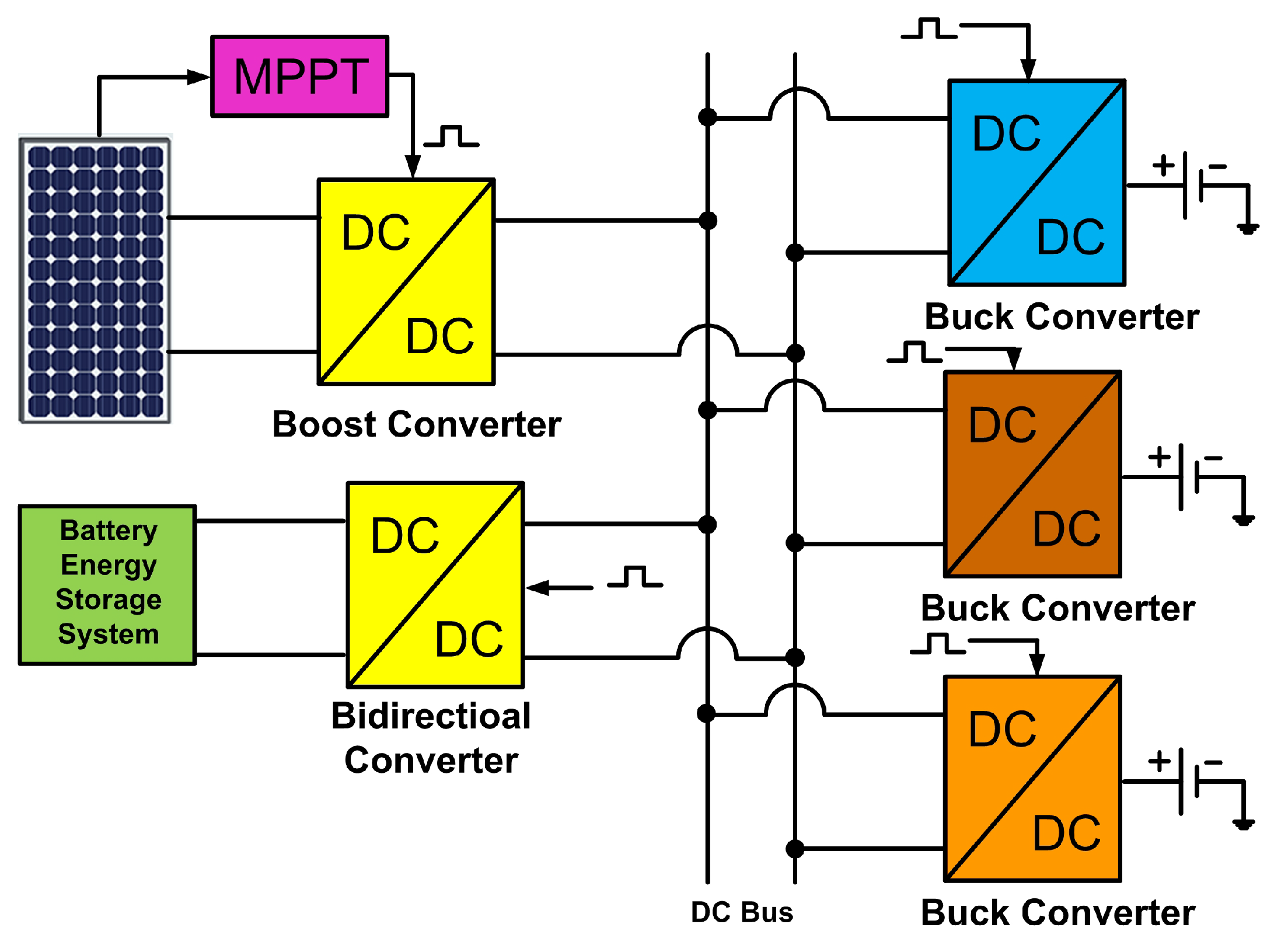

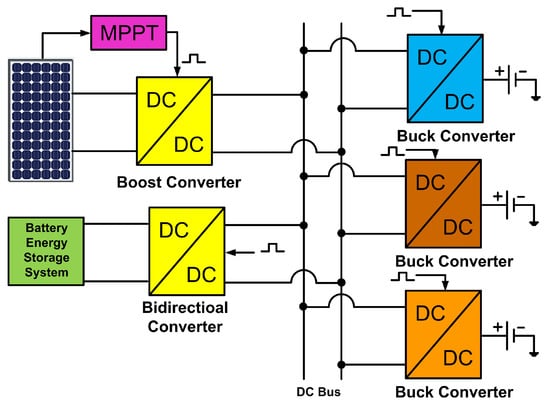

In Ref. [91], the authors Yesheswini et al. have proposed a DC-DC converter-based system for charging multiple EVs simultaneously. The system is a solar-fed battery charging system with a boost converter, backup battery, bidirectional converter, and buck converter to charge EV batteries. The system proposed by the authors is shown in Figure 10. The authors have chosen a 36 V, 28 Ah lead-acid battery for simulation. The solar PV source is chosen to be composed of two 180 W panels connected in parallel. The solar-fed converter is controlled using the perturb and observe (P&O) maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithm, while the battery charging is simulated using the CC-CV charging algorithm. A bidirectional converter connects the station battery with the DC grid, facilitating charging and discharging based on the requirement. The station battery will support the charging whenever the solar PV supplies low power (lower than the EV requirement). The station battery will be charged when the solar power is in excess. The station battery is also used to maintain a constant DC bus voltage. The hardware prototype is implemented using a lead-acid battery with the buck converter (with IRFP460 MOSFET) controlled using an STM controller. The switching frequency is chosen to be 4 kHz. The authors have analyzed the performance of the converters for EV battery charging. As a future scope, the authors have suggested optimizing sources such as solar, wind, and biofuels, using various controllers and machine learning methods to optimize the load on the charging station. The proposed system has used solar and battery energy storage systems as the two sources. Therefore, the current rating will be limited, especially considering the intermittency of solar energy. Since the system does not involve a grid connection, so that power will be limited, it is hence not very suitable for fast charging.

Figure 10.

System proposed in Ref. [91] for simultaneous charging of multiple batteries.

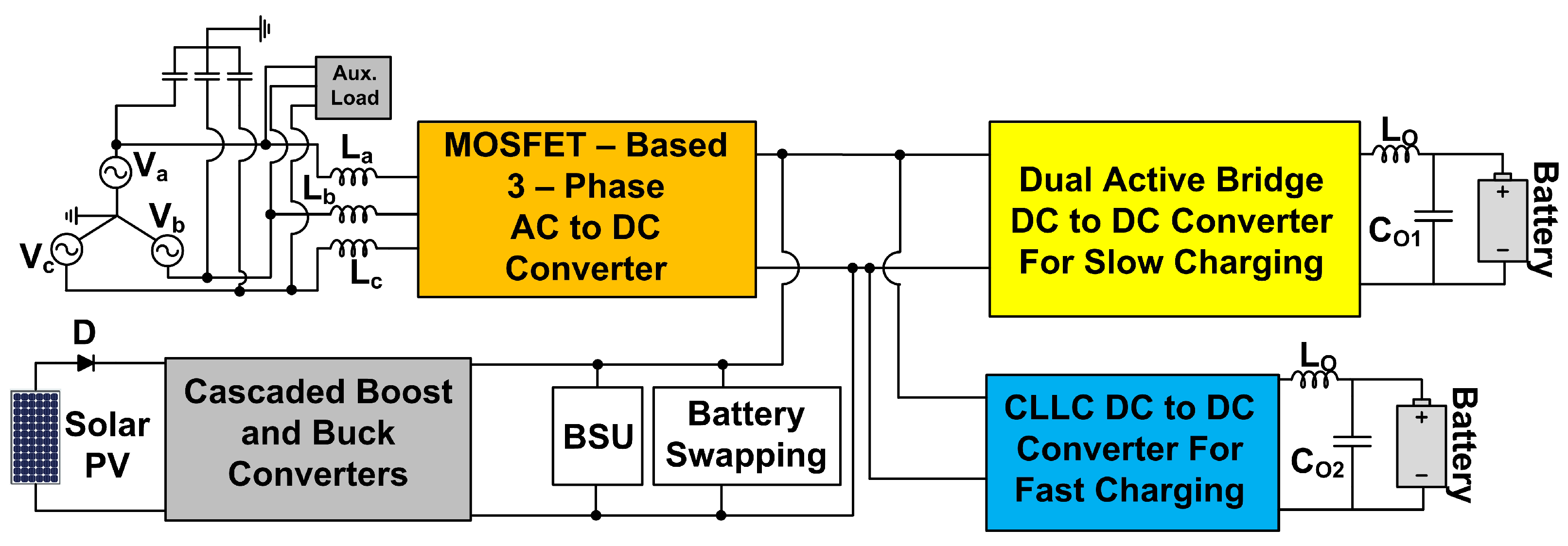

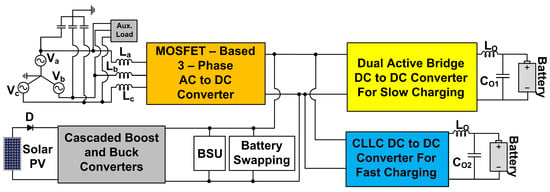

Mishra et al. [92] have proposed a grid and solar-based hybrid charger that is controlled using adaptive supervisory control (ASC). The topology used by the authors is shown in Figure 11. The proposed topology uses two isolated converter stages (one DAB and one resonant converter), one working as a slow charger and the other as a fast charger. In addition, a PV-fed DC-DC converter with a battery storage unit (BSU) is considered as shown in the figure. The grid-side converter (GSC) is an active bridge AC to DC converter used to regulate the DC link voltage and to ensure PFC. It is operated at a frequency of 10 kHz. A PR controller-based closed loop is used to control the GSC. In the PV-fed converter, the incremental conductance algorithm is implemented for MPPT. The BSU is the battery pack with a buck-boost bidirectional converter. The DAB is controlled to have zero voltage switching (ZVS) with bidirectional power transfer. When only the grid supplies power, the slow charger is utilized to charge the EV batteries, while slow and fast chargers are used when both the grid and PV supply power to ensure minimal stress on the grid. The proposed system is very suitable for simultaneous fast and slow charging. Battery swapping function is added along with a storage unit that can be used as a backup source. The proposed system can be used to charge high-power, high-voltage batteries. However, a higher number of components could pose reliability issues.

Figure 11.

Topology of the converter proposed in Ref. [92] for multi-battery charging.

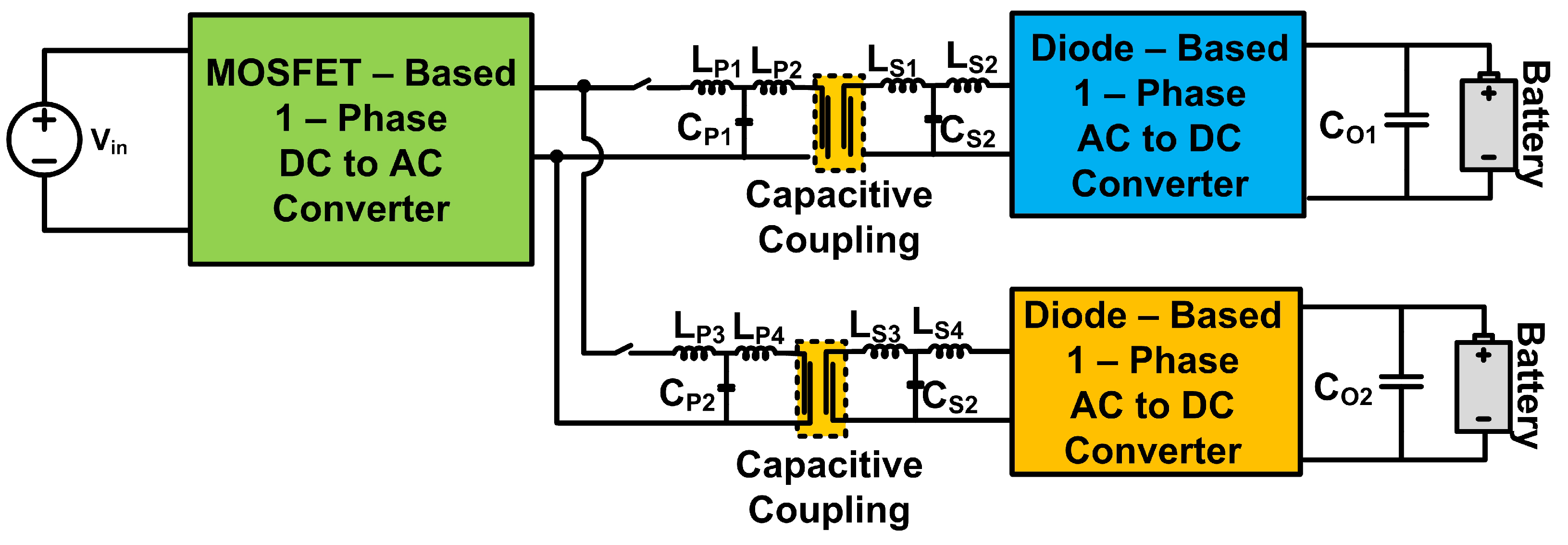

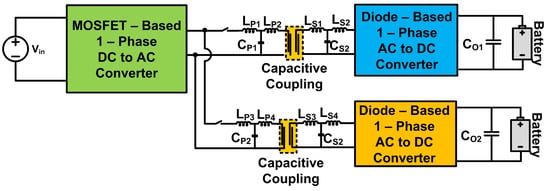

In Ref. [93], Vu et al. have proposed using a multi-input capacitive coupled wireless charger for EV battery charging. The block diagram is shown in Figure 12. Capacitive power transfer (CPT) topologies have high leakage capacitance, which is usually compensated for by using resonant inductors. However, the authors have pointed out that this method is unsuitable for high-power applications, and that LCL topology is more suitable. The authors have provided a detailed analysis of the CPT system. A DC input voltage of 250 V is chosen with a variable output of 120 to 270 V. The switching frequency of 1 MHz is chosen for the system. Cross-coupling is avoided by selecting a distance of 150 cm between both primary plates. Simulation results are provided for the proposed system for equal and unequal load conditions of the two converters. With the wireless power transfer of the capacitive type, the main issue is the distance of separation between the transmitter and the receiver. In addition, the efficiency of wireless transfer is less. With the use of diode rectifiers as proposed by the authors, the receiver side circuit also needs to be controlled from the transmitter side, making the control less flexible.

Figure 12.

Capacitive coupled wireless charger for multi-battery charging in Ref. [93].

Fan et al. [94] have proposed a reflex charging technique to charge two batteries simultaneously. The authors have used ‘N’ sets of interleaved buck-boost converters to obtain reflex charging. The modes of operation and the corresponding equivalent circuits have been explained. Phase shift control has been employed to control the converters in this work. This is also said to prevent over-charging or over-discharging. In addition, a battery charge-discharge management system has been proposed to maintain the battery voltage. The authors have validated the system by charging two 12 V batteries from 17 to 24 V input. The experiment for N = 1, 2, 3, and 4 sets have been provided. Both positive and negative battery currents have been obtained, validating the two states of operation based on the power switch operation. Since the proposed system uses buck-boost converters, isolation is not provided and is only suitable for low-power charging at lower voltages.

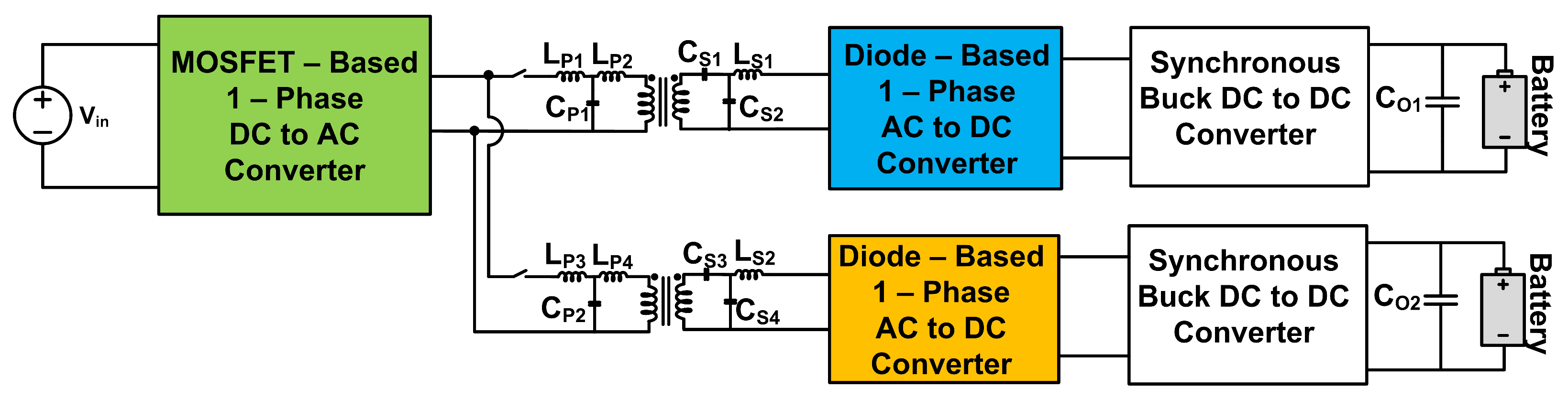

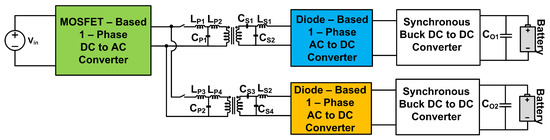

Vu et al. [95] have proposed a multi-output inductive wireless power transfer (WPT) charger for simultaneously charging two batteries. A standard full-bridge voltage source inverter is used to convert DC input to AC, which is then passed to two compensation networks of inductors and capacitors with high-frequency transformers, which feed two diode rectifiers separately in cascade with synchronous buck converters (SBCs). The output of the SBCs is used to supply the two batteries, which charge simultaneously. The circuit diagram proposed by the authors is shown in Figure 13. The AC equivalent circuit of the inductive power transfer system with its analysis has been provided to calculate the coupling coefficient. The frequency is kept constant during the operation, and the secondary side converter functions as the charger controller. The resonant tank circuit components design has been provided for the proposed converter. A DC input voltage of 400 V is chosen to obtain a variable output of 250 to 400 V. A switching frequency of 68 kHz was used for the simulation. Unequal loads have been used to simulate the system to validate the circuit operation and simultaneous charging of both batteries. With WPT, the two primary challenges are the separation distance between the two coils and the lower efficiency of power transfer. The proposed system can be used to charge batteries of unequal ratings. Synchronous buck converter provides better control possibility but limits the power. Hence the system is not very suitable for fast charging.

Figure 13.

Circuit topology proposed in Ref. [95] to simultaneously charge two batteries.

Chakraborty et al. [96] have proposed a pulse charging-based Li-ion battery charging converter. The main power supply working as a current source (equivalent) is connected in a predefined order, in parallel, with different batteries using a set of switches. At any given time, one battery is being charged. This is decided by turning the selector switch (S1, S2 or S3) ON and OFF to connect or disconnect the respective battery. If all batteries are charged, a reset switch is used for freewheeling the inductor energy. The controlled current source uses the forward converter topology with a core reset. A number of MOSFETs and diodes are used to implement the switch selectors. For ‘n’ battery cells connected in series in each switch selector block, 2n+2 MOSFETs and 2n diodes are required. Thus, if three battery cells are connected in series for one switch block, say, S1, then eight MOSFETs and six diodes are required for making that selector switch. Charge balancing is implemented along with charging and discharging using the pulse charging technique. A two-output case is simulated using the parameters of the VALENCE 444 Li-polymer cell. The converter is fed from a 170 V AC supply with the maximum duty cycle limited to . The switching frequency selection is flexible, and average current control is used to control the inductor current. The proposed system uses a higher number of components, especially when multiple batteries are to be charged simultaneously. In addition, the power limitation leads to slow charging and is not suited for charging vehicles at higher voltages.

In continuation with the previous work [96], Chakraborty and Mohan [97] have extended the work to a wider range of medium-power AC-DC applications. The suitability of CCM and DCM has been evaluated. Negative voltage feedback reduces the bus voltage stress, with a trade-off that includes an increase in the input current distortion. The advantages of the voltage doubler rectifier topology are provided in detail, and the corresponding simulation waveforms have been provided. The input current THD is around 60% and a simulation efficiency of has been obtained with an input of 110 V AC.

Table 1.

Comparison of the various converters considered in Section 4.

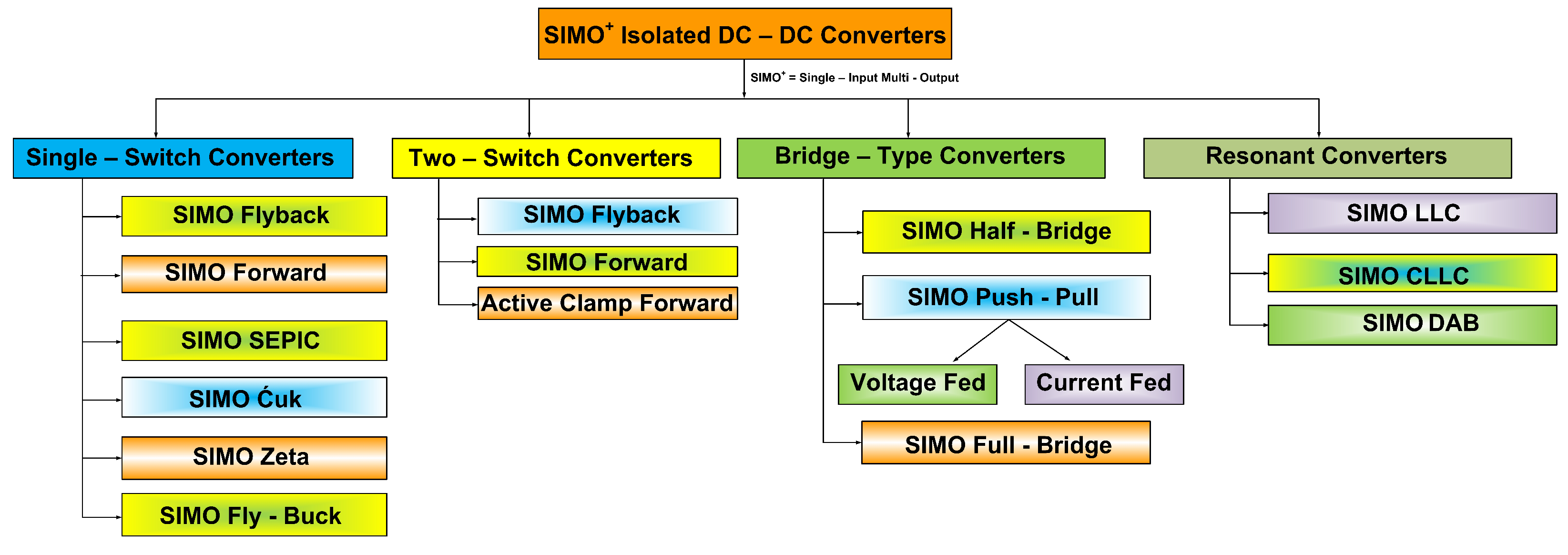

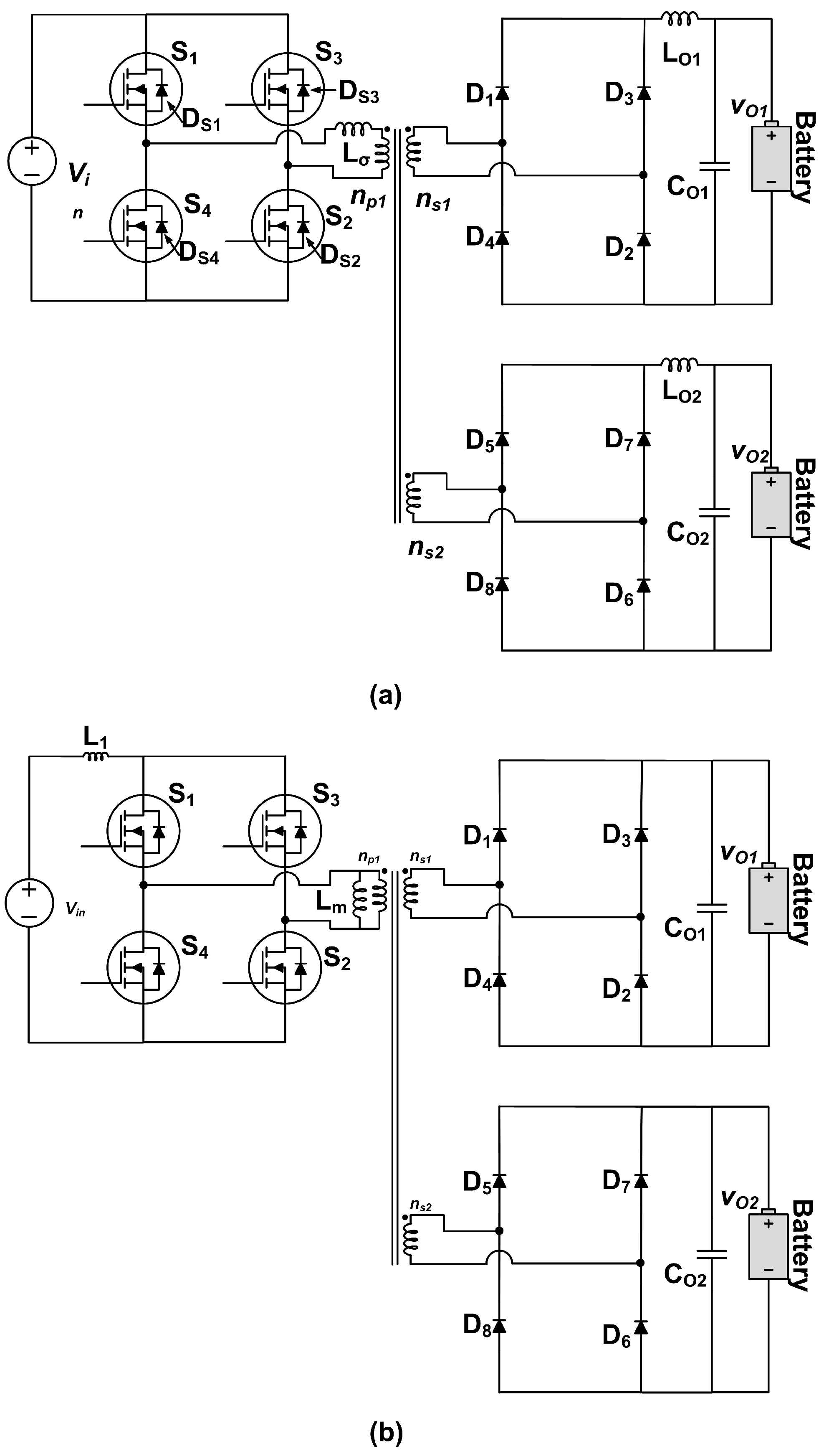

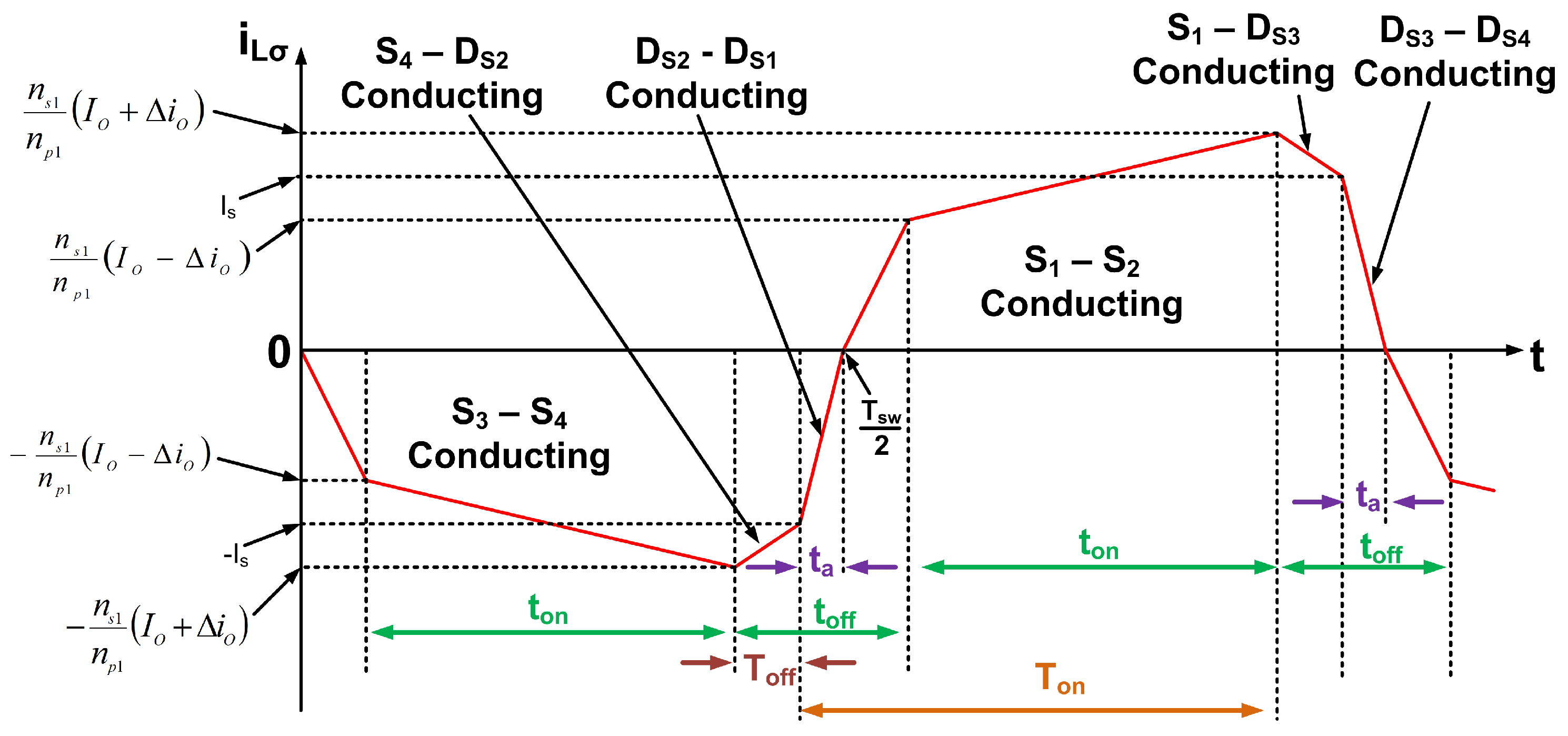

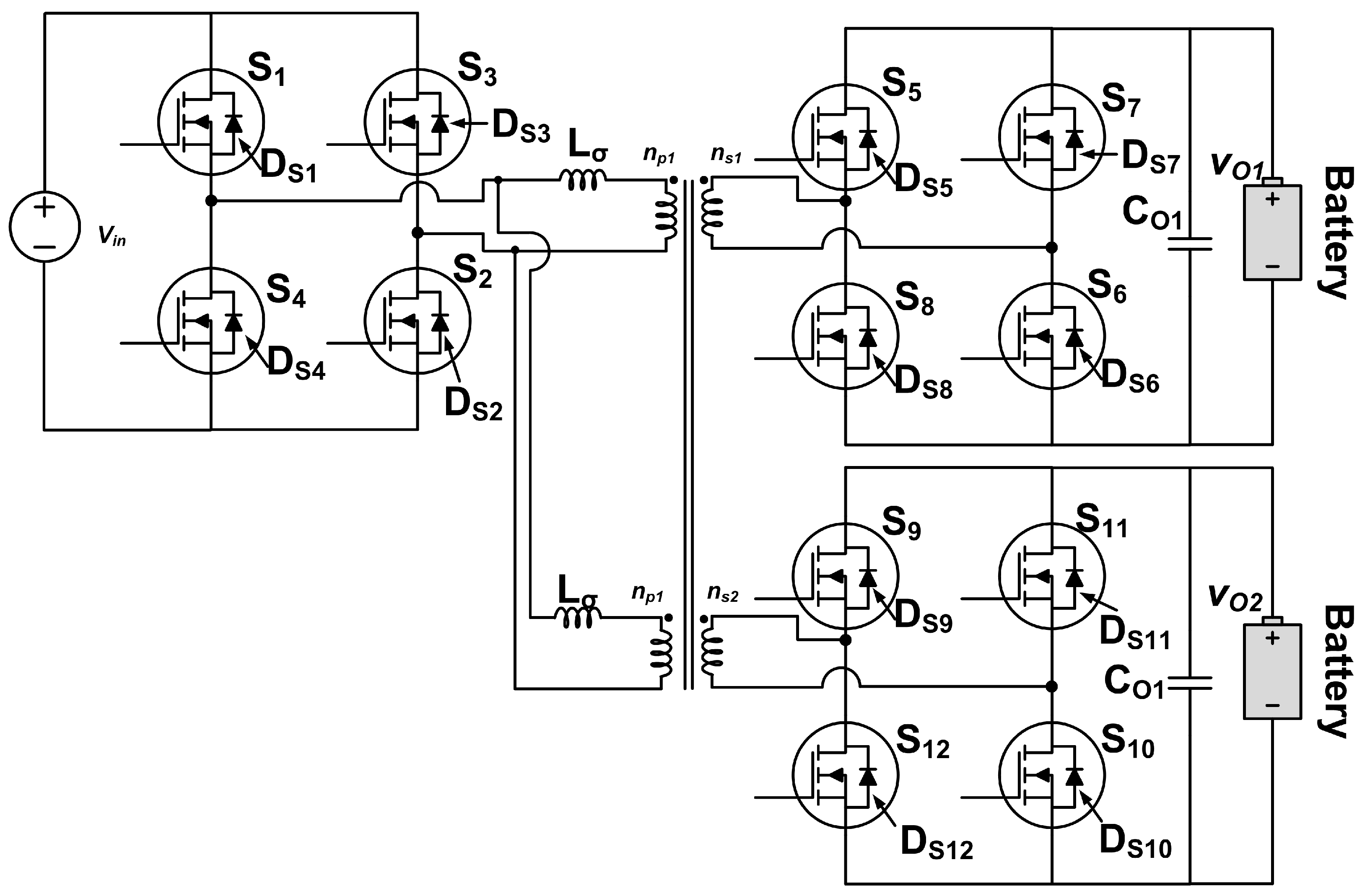

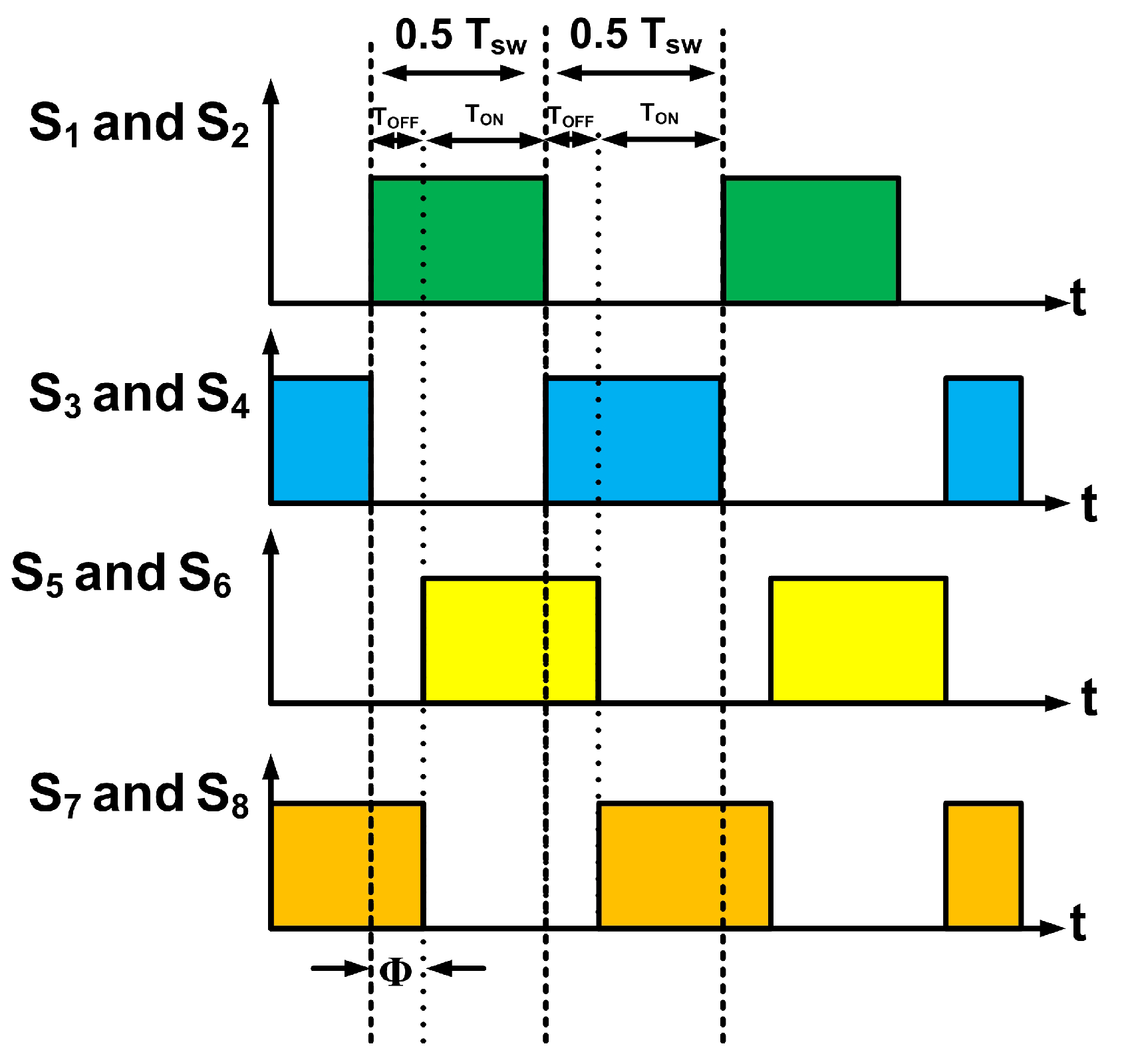

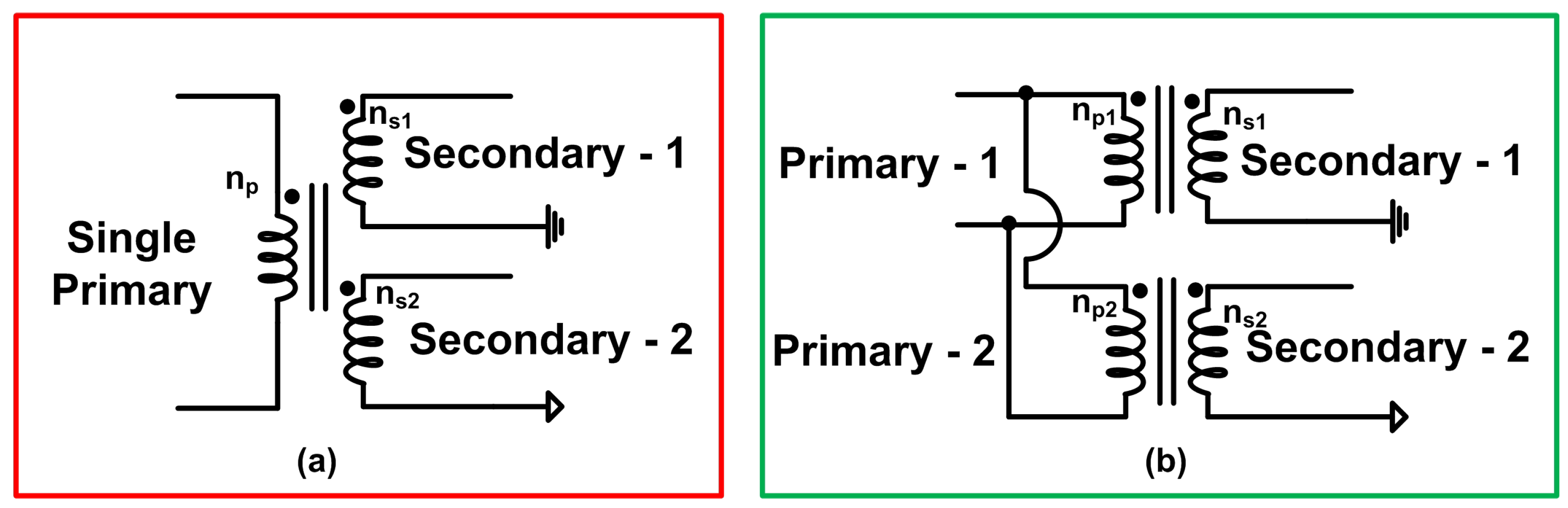

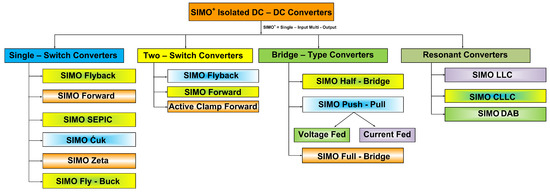

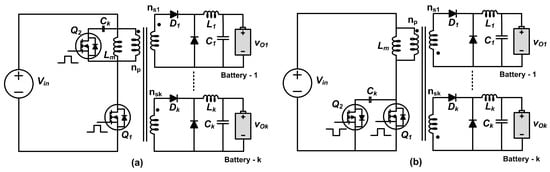

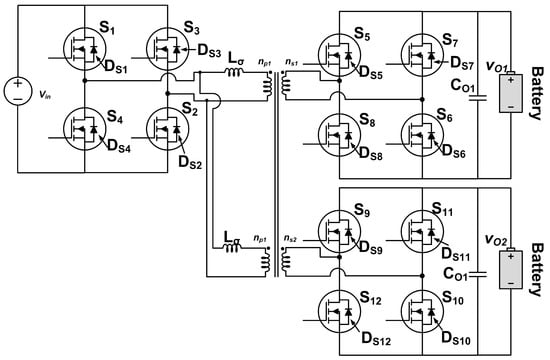

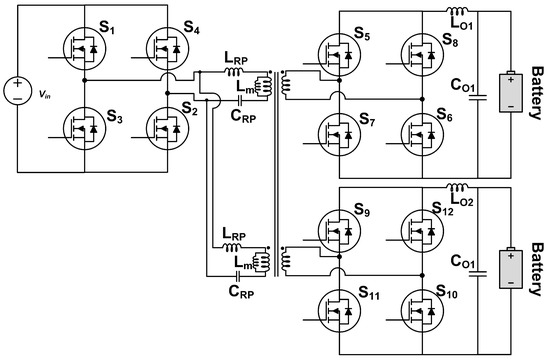

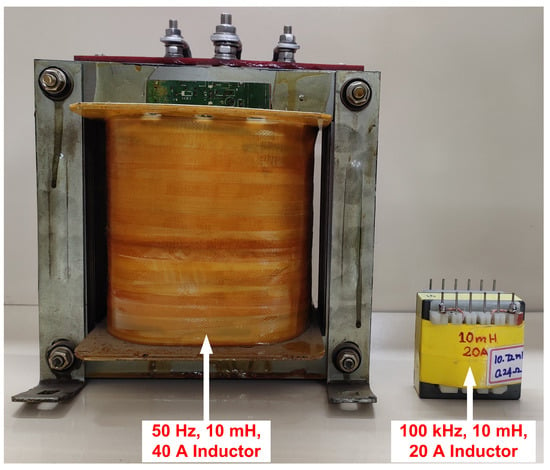

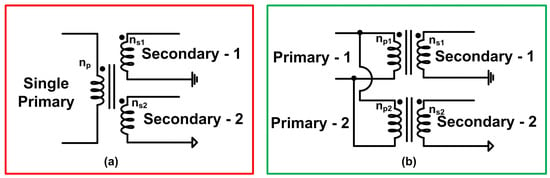

5. Potential Extension of Existing Isolated DC-DC Converters for Simultaneous Charging of Multiple EV Batteries

Simultaneous charging of multiple EV batteries requires multi-output DC-DC converters. For high-power applications such as battery charging, isolated converters are preferred. While several isolated DC-DC converter topologies exist in the literature, all the topologies cannot be used to get the same performance characteristics for EV battery charging applications. This section provides some potential isolated DC-DC converter configurations for simultaneously charging multiple Li-ion batteries. Galvanic isolation is required between the different circuits of the charger to ensure safe and reliable operation [42]. A classification of the most common Single-Input Multi-Output (SIMO) Isolated DC-DC converters is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Classification of common SIMO DC-DC converters.

The choice of a DC-DC converter for EV battery charging depends on the following factors [98]:

- Power rating and power density;

- Isolation requirement;

- Charging type (AC/DC charging, slow/fast charging);

- Current rating (affects the choice of cable);

- Type of switch used (depends on the frequency of switching, which decides the magnetic component size);

- Number of outputs required;

- Voltage at each of the output terminals;

- Cost, size, and weight of the system.

The appropriate topology is to be chosen based on the trade-offs between the factors. With the mass usage of EVs, infrastructure needs to be developed to facilitate charging. The infrastructure in developed countries is better than that in developing nations. During infrastructure development, the land size, availability of power supply, the possibility of extension for future needs, types of vehicle, charging station layout, cabling cost, distance, incentives, and other factors need to be considered [99]. Location, cost, waiting time, charging time, and payment options are some of the most critical factors from the consumer’s point of view [100]. The locations could include workplace parking areas, shopping malls, and public parking structures [99]. The waiting time needs to be reduced in addition to the reduction of charging time to attract consumers to a particular charging station. Presently available infrastructure will significantly affect the further expansion and installation of new chargers. In this scenario, many of the above-mentioned factors will be predefined and can pose some limitations during expansion. Care has to be taken, especially regarding the ratings of the components, protection system, and communication protocols during expansion. The expansion needs to be planned, modeled, and programmed considering the present infrastructure along with the pattern of transportation expansion [101]. It can be taken up as an optimization problem with the existing infrastructure limits as the constraints [102].

Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3, Section 5.4 and Section 5.5 describe the various converters that can simultaneously charge two or more batteries. Some converters are limited to low-power applications, while others can be used for high-power applications. All descriptions related to this are provided in this section. In addition, power loss estimation (assuming ideal passive elements) is described for the converters that are more commonly used for battery charging.

5.1. Single-Switch Isolated DC-DC Converters

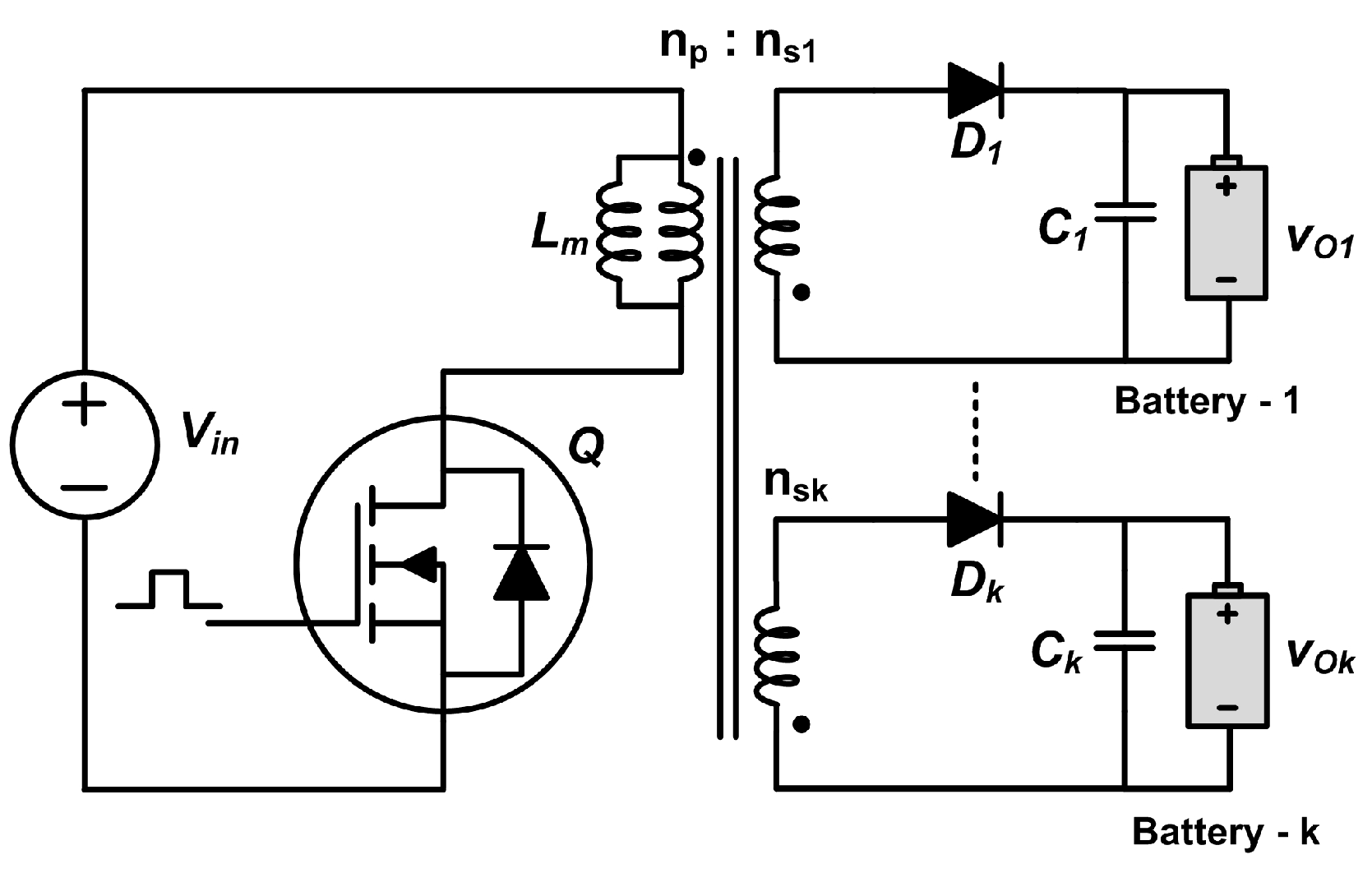

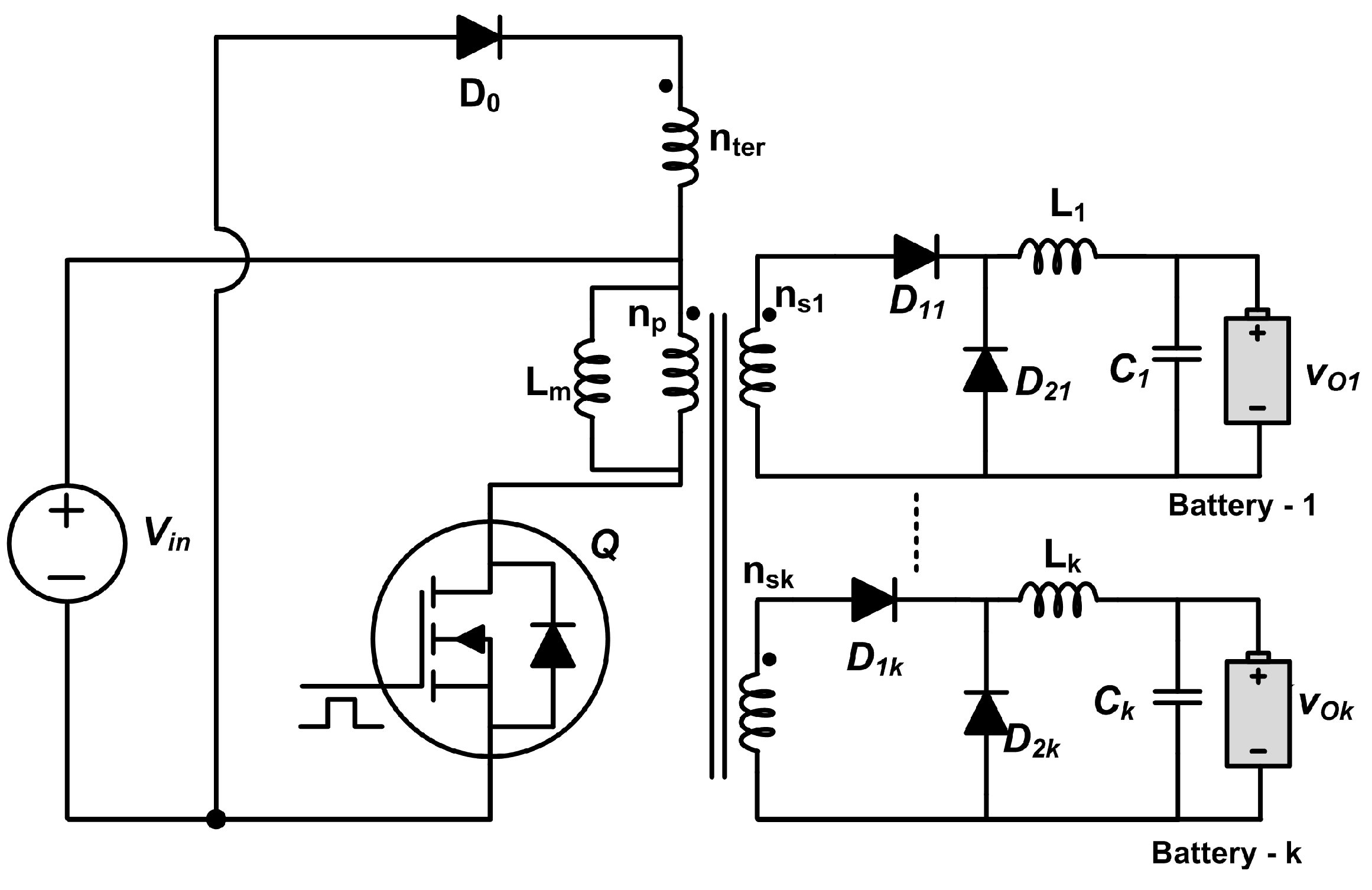

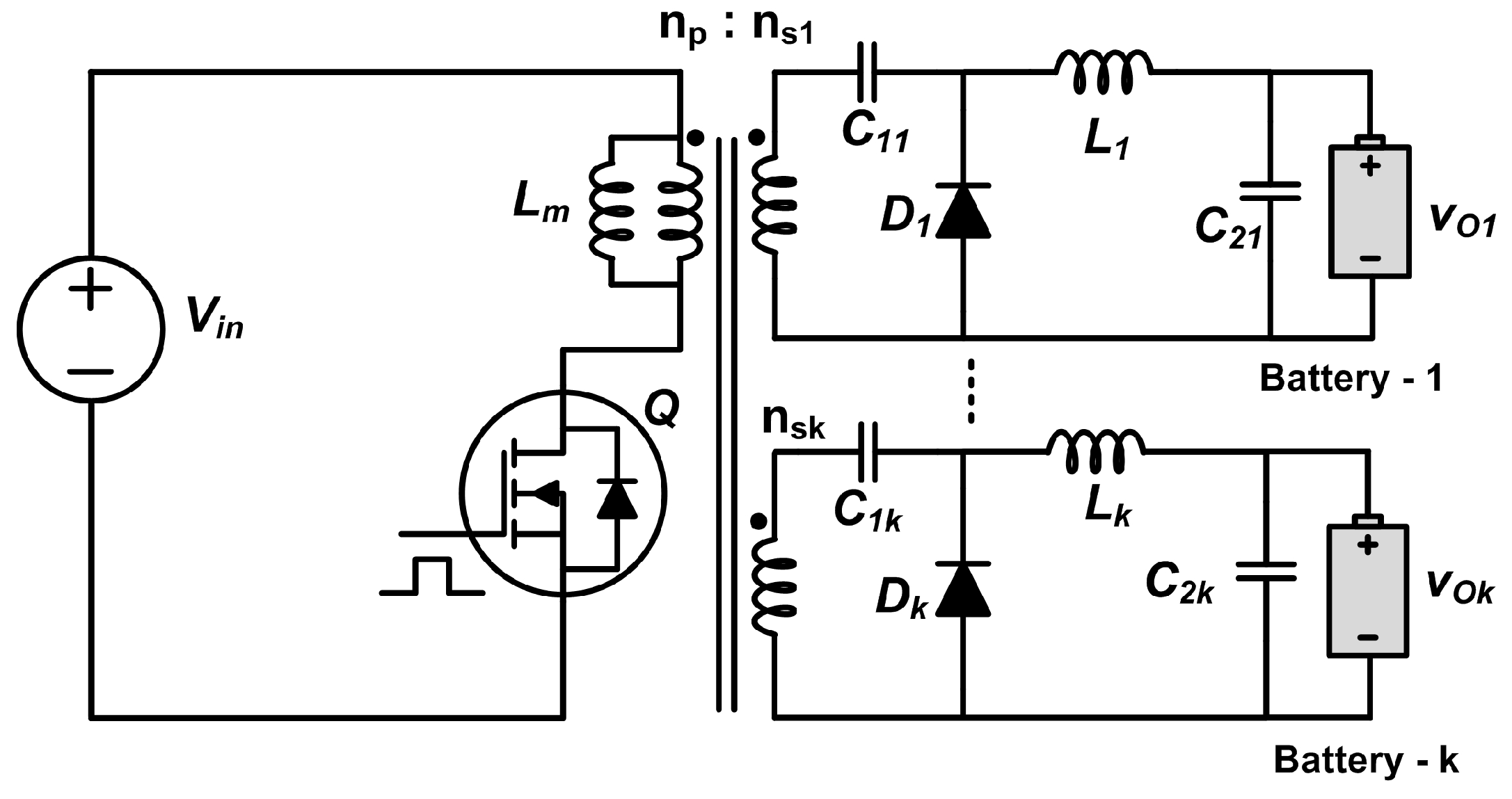

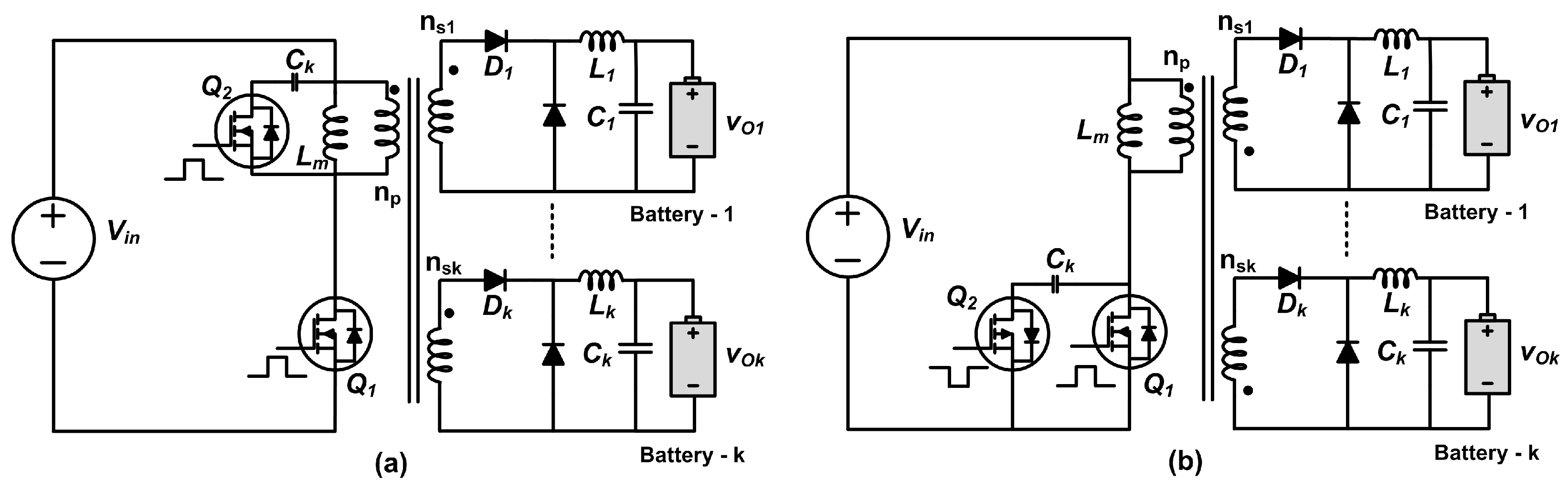

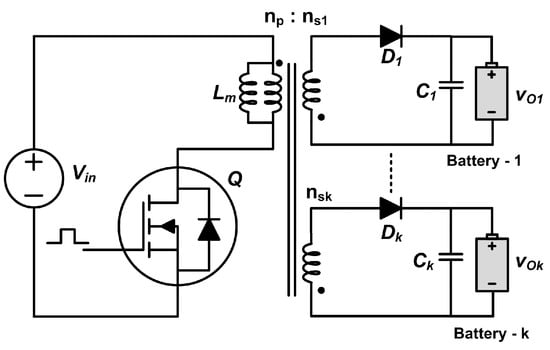

5.1.1. Single-Switch Multi-Output Flyback Converter

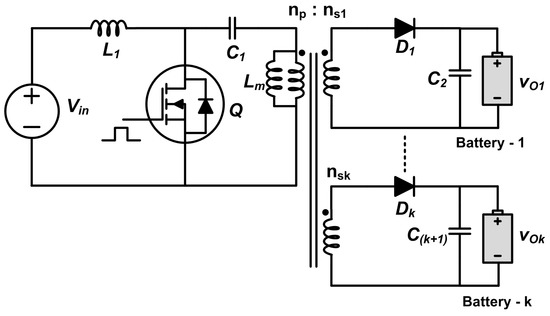

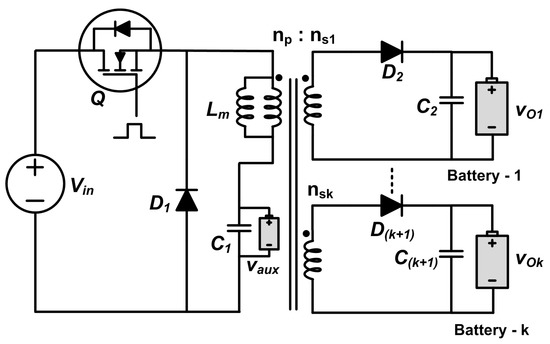

The flyback converter is an isolated buck-boost topology that can be modified to implement multi-battery charging. The basic flyback converter uses one active switch (MOSFET/IGBT), diode, capacitor, and transformer. Theoretically, ‘k’ number of batteries can be charged using a flyback converter if a transformer with ‘k’ number of isolated secondaries is used [103], as shown in Figure 15. Getting multiple outputs does not involve much difference in complexity, space, or cost since each additional output requires one HFT, one diode, and one capacitor. The converter gives relatively good efficiency at a low cost. The equation for each of the outputs (in CCM) is given by Equation (2), where is the duty cycle. However, this topology has one major limitation. The typical power limitation of a flyback converter is approximately 60 W [104] (less than 100 W, in general). Hence, the converter could charge and discharge the low-voltage auxiliary battery of the EV or low-power vehicles such as e-bicycles or low-power two-wheelers. The other disadvantages include high stress on the switch, relatively higher conduction losses, and the requirement of a snubber. The choice of switching frequency and ratings of the various components depends on the type of source available and the rating of the battery, which will decide the duty cycle value. The design of the multi-secondary flyback transformer is a critical design criterion that needs to be considered. The magnetizing inductance value needs to be greater than a minimum value () to ensure CCM. This is given by Equation (3). To ensure CCM operation, the inductance value should be greater than value. Since the inductance chosen should be greater than , it could lead to design issues if too high or too low inductance is chosen. Hence, the required inductance can be calculated using Equation (4) and then verified if it is greater than or not.

Figure 15.

Single-switch flyback converter with ‘k’ number of secondary windings.

The capacitance of the capacitor across the load can be calculated using Equation (5), where R is the equivalent load resistance.

A capacitor (Cin) can be connected across the source if the input is noisy. Such a capacitance can be calculated using Equation (6).

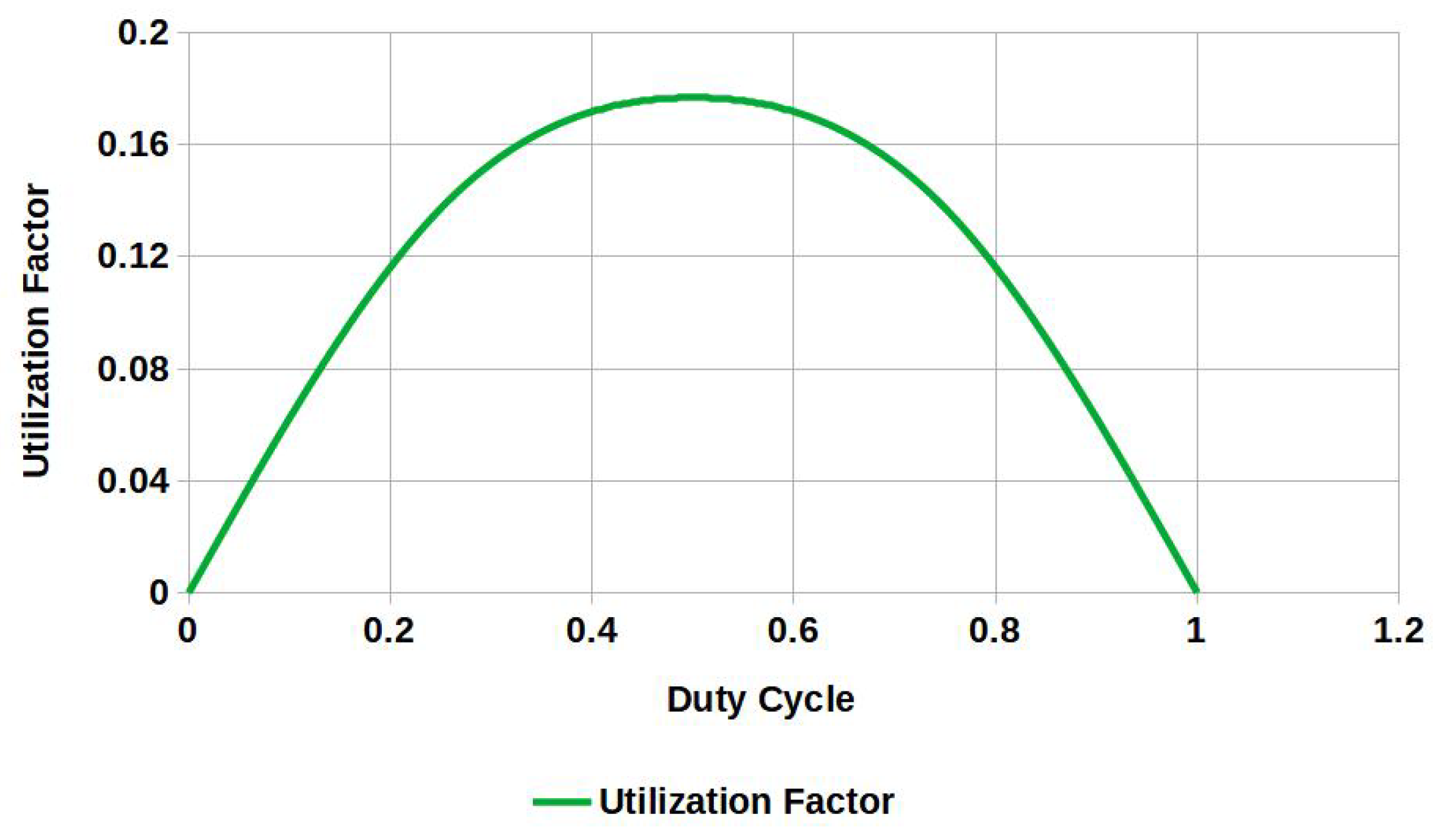

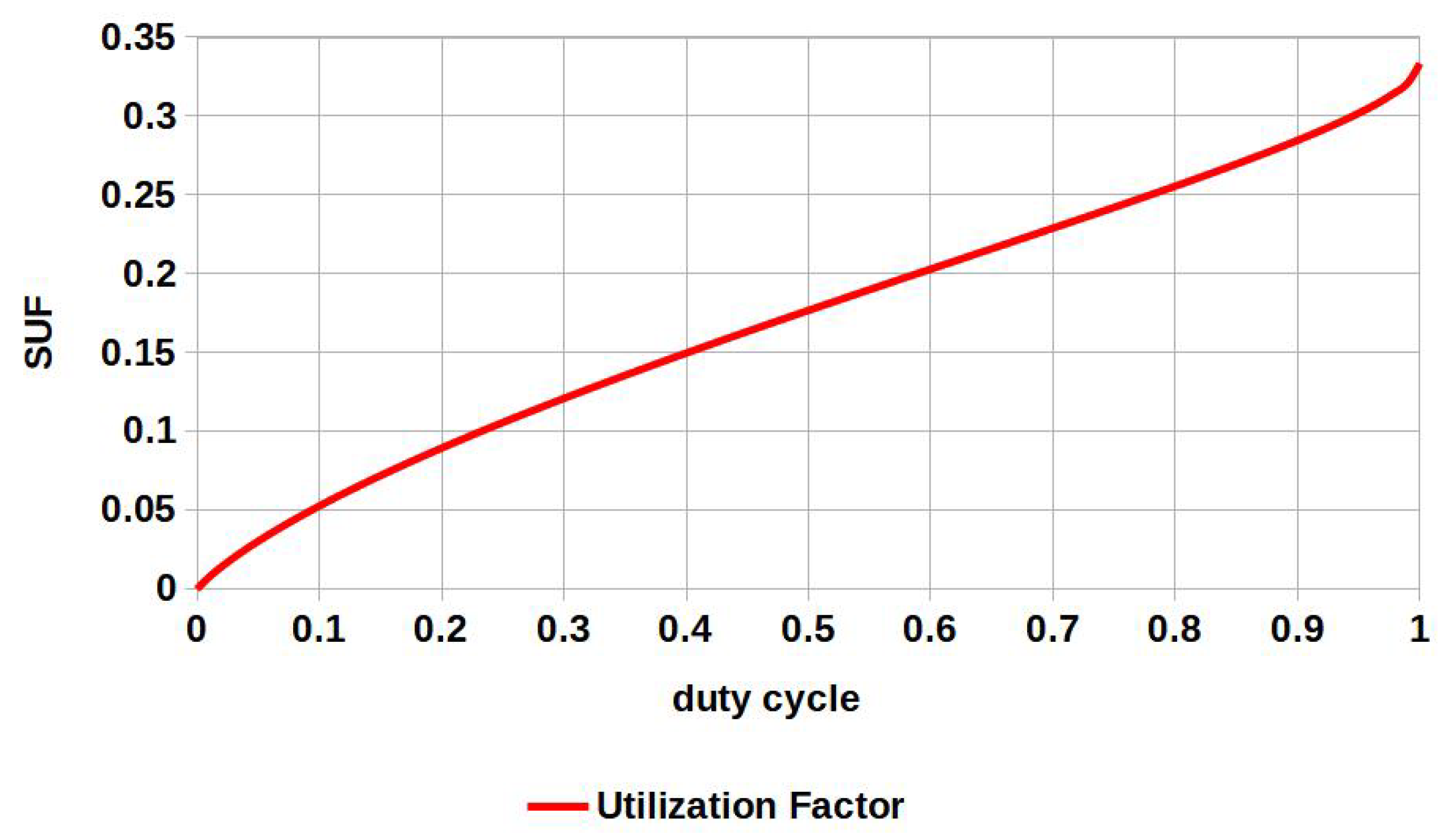

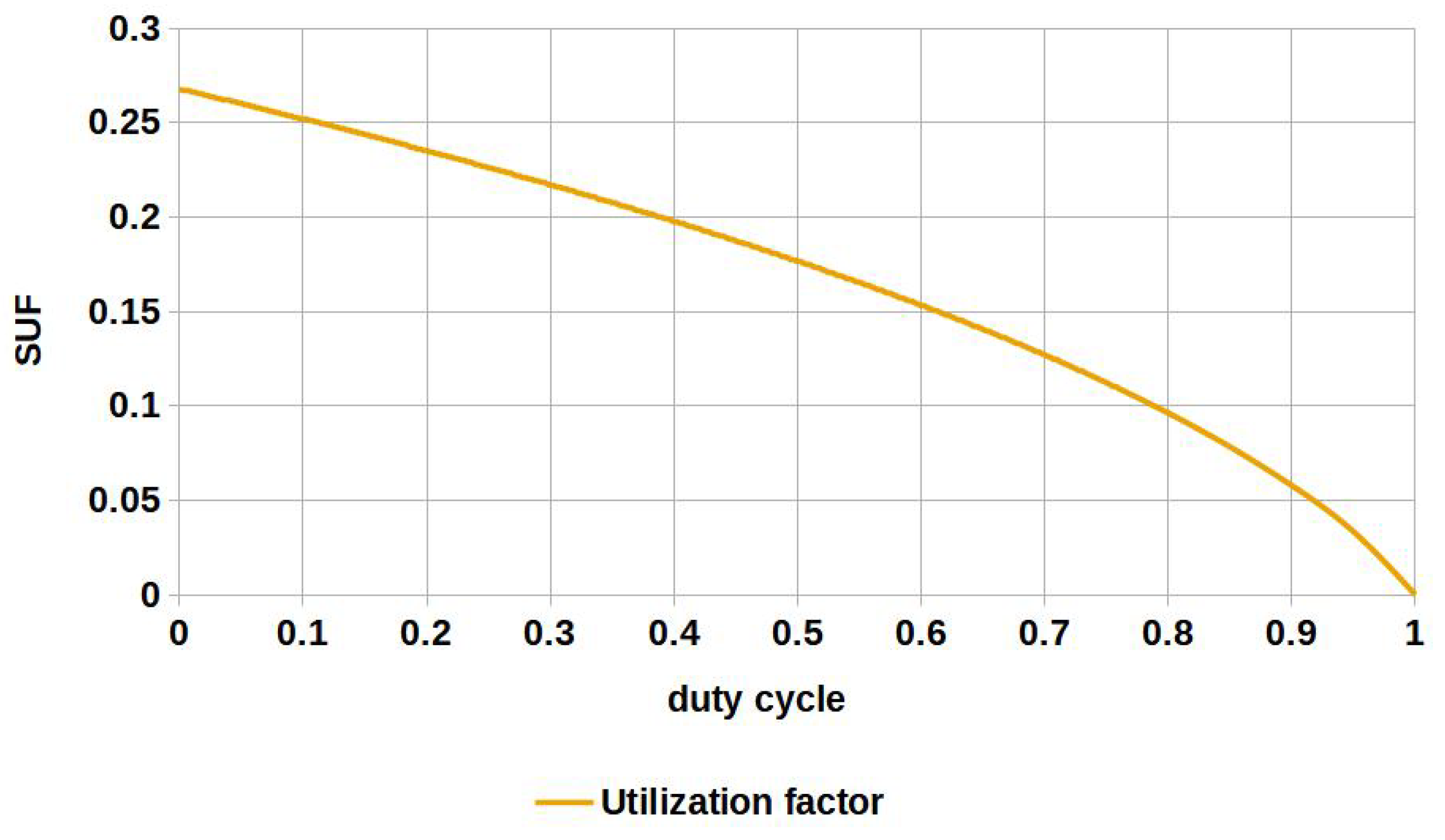

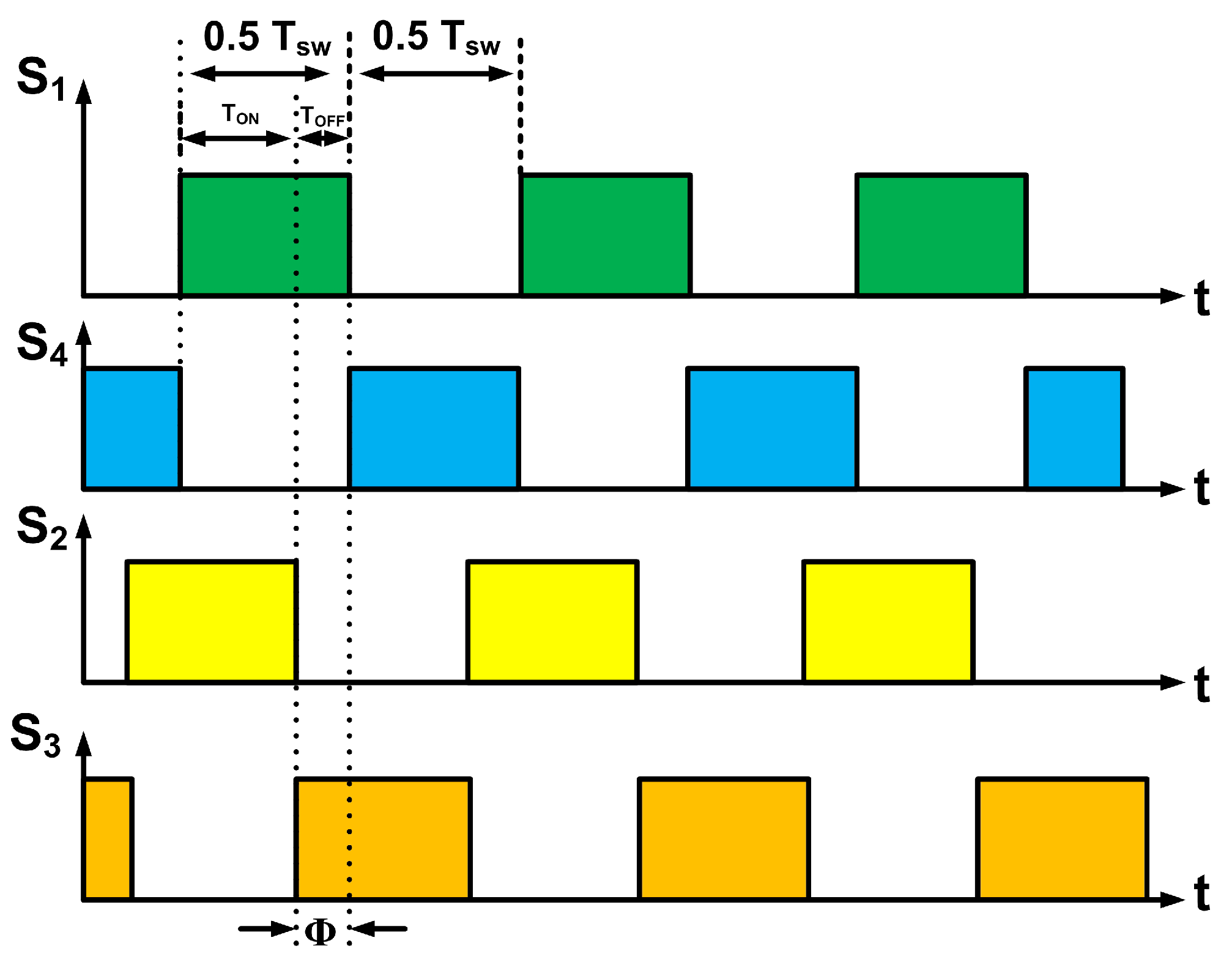

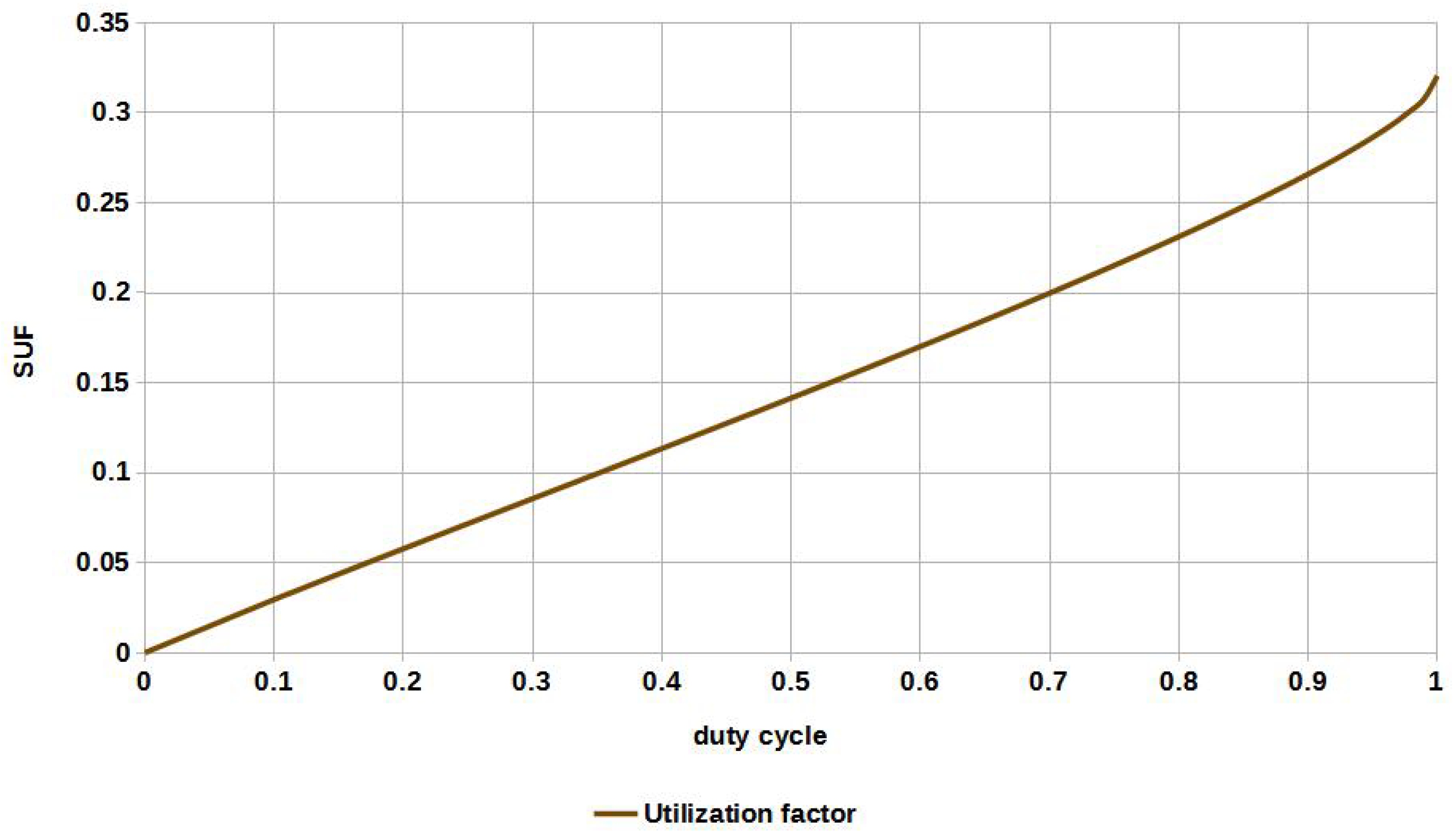

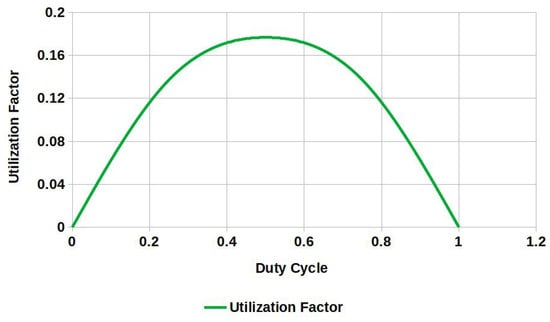

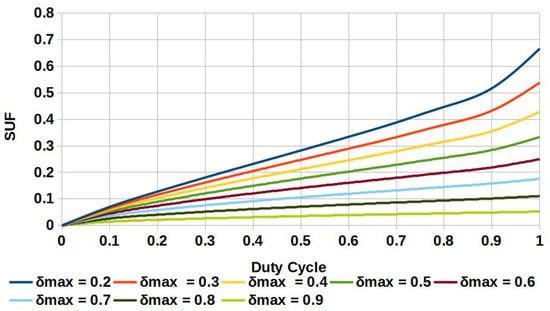

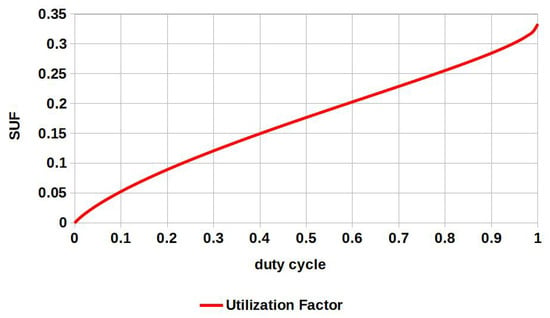

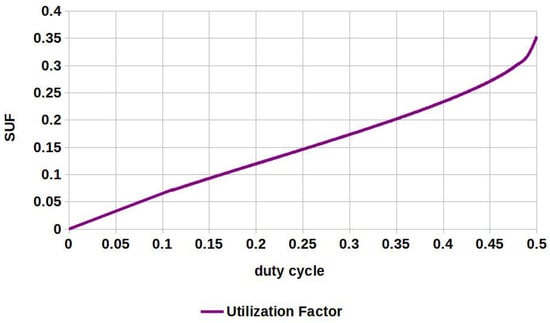

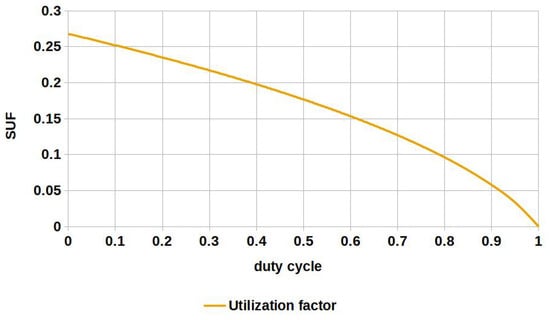

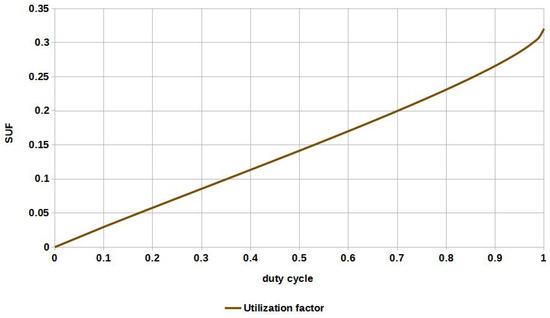

The semiconductor utilization factor () is given by Equation (7). A plot of for duty cycles from 0 to 1 is shown in Figure 16. It can be seen from the graph that the is the highest when the converter is operated at a duty cycle of 50% [105]. Therefore, it is better to operate the flyback converter at or around the duty cycle values of 50%.

Figure 16.

Semiconductor utilization factor of the flyback converter.

The conduction losses in the MOSFET and each diode can be estimated using Equations (8) and (9), respectively [105].

where is the on-state resistance of the MOSFET, is the on-state resistance of the diode, is the average value of the input current, and is the threshold voltage of the corresponding device (MOSFET or diode). Based on the turn-off energy loss characteristic (, and ) provided by the manufacturer for the 100FIT test voltage (; it is the voltage across the device such that there are 100 failures within h of operation [106]; FIT is Failures In Time), we can estimate the average value of the switching loss in the diode [105] using Equation (10).

Similarly, the average value of the switching loss [105] in the MOSFET () is estimated using Equation (11).

where , and are the turn-off energy loss characteristic provided by the manufacturer for , and , and are the turn-on energy loss characteristic from the MOSFET data-sheet.

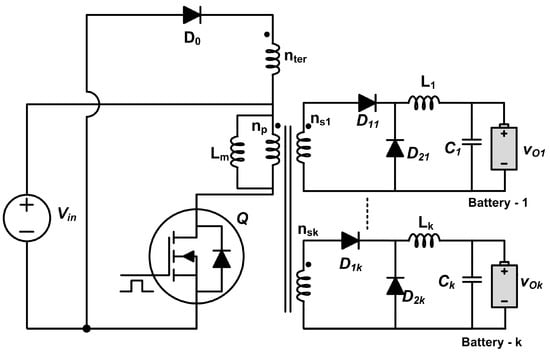

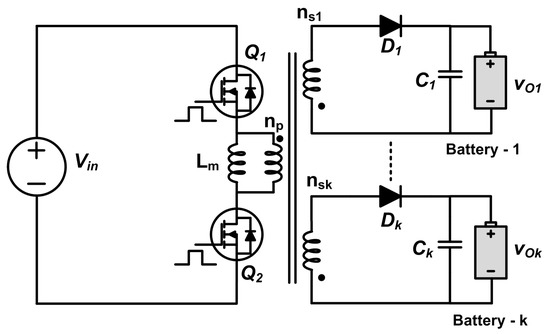

5.1.2. Single-Switch Multi-Output Forward Converter

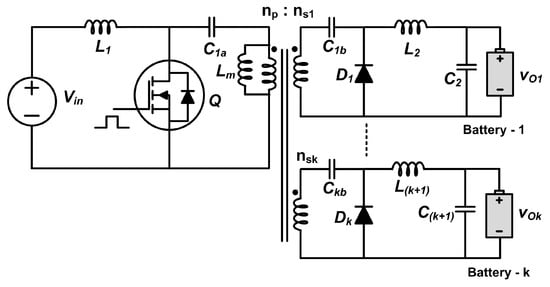

The other popular isolated converter is the forward converter. It is an isolated version of the popular buck converter. Compared to a flyback converter, it gives a faster transient response, better efficiency, and low output ripple. However, the cost is higher when compared to that of a flyback converter. It is generally used whenever a high current output is required [107]. The major limitation of the forward converter is the duty cycle. Its maximum duty cycle must be about 50%. The forward converter uses a tertiary winding () and a diode to enable core reset. The high-voltage winding usually provides the core reset. The time taken to reset is inversely proportional to the winding voltage. Figure 17 shows the implementation of a forward converter with multiple winding to enable simultaneous charging of batteries. Similar to a flyback converter, the forward converter also has a power limitation of 100 W [103]. The output of the kth winding is related to the input as given by Equation (12). The magnetizing inductance (), output inductance () and output capacitance () can be found using Equations (13), (14) and (15), respectively. If the input is noisy, a capacitor () with a value calculated using Equation (16) can be connected across the source.

Figure 17.

Single-switch forward converter with ‘k’ number of secondary windings.

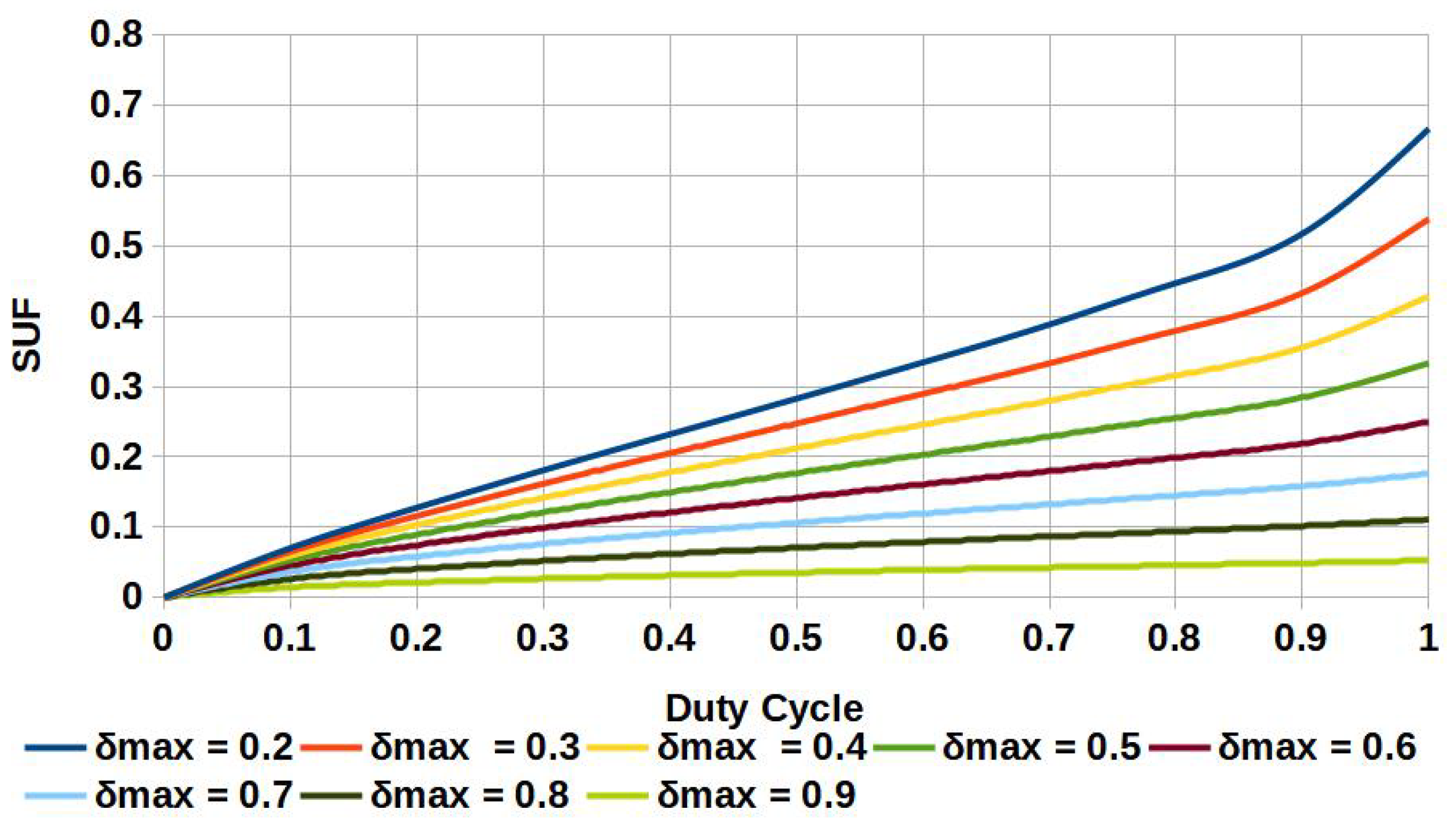

The semiconductor utilization factor () for the forward converter [105] is given by Equation (17). The choice of transformer turns ratio () plays a vital role in obtaining optimal semiconductor utilization factor since the depends on , which depends on the transformer turns ratio. Optimal leads to optimal converter design. A plot of duty cycle () vs. can be plotted to obtain the corresponding optimal turns ratio of the transformer. An example of such a plot is shown in Figure 18 for various between and .

Figure 18.

Semiconductor utilization factor of the forward converter.

The average value of conduction loss of the switch Q, and three diodes , , and are given by Equations (18), (19), (20), and (21), respectively [105].

Before calculating the switching losses, we note that the switching loss in diode is negligible since it is turned OFF when the current reaches zero. Therefore, switching losses must be calculated for switch Q and diodes and . The corresponding switching losses are estimated using Equations (22), (23) and (24), respectively [105]. The W, x and y coefficients have the same meaning as described before.

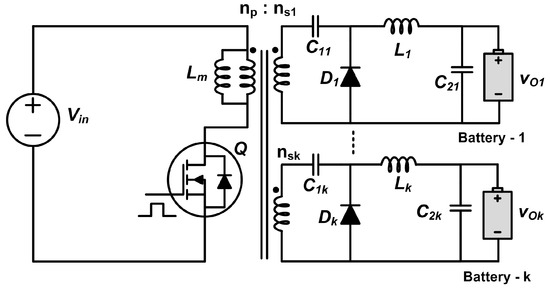

5.1.3. Single-Switch Multi-Output Isolated SEPIC

The Single-Ended Primary Inductor Converter (SEPIC) is a popular buck-boost-derived converter. A transformer replaces the inductor of the non-isolated SEPIC with proper dot polarity to obtain the isolated version of the converter. This converter can be modified to charge multiple batteries simultaneously, as shown in Figure 19. It provides an output voltage described by Equation (25). The advantage of isolated SEPIC is that the input current has low ripple and hence is suited very well when the input to the charger is provided from solar PV panels. Adding multiple outputs does not significantly increase cost since each additional stage requires only an HFT, a diode, and a capacitor. The input inductance, input capacitance, magnetizing inductance, and output capacitance are calculated using Equations (26), (27), (28), and (29), respectively [105].

Figure 19.

Single-switch isolated SEPIC with ‘k’ number of secondary windings.

The semiconductor utilization factor of an isolated SEPIC is the same as that of a flyback converter and is given by Equation (7). The conduction losses in the MOSFET (Q) and diode () can be estimated using Equations (30) and (31), respectively [105].

where is the ON-state resistance of the diode and is its threshold voltage. The average switching loss in diode [105] is given by Equation (32).

where,

5.1.4. Single-Switch Multi-Output Isolated Ćuk Converter

The Ćuk converter is another popular buck-boost-derived converter. It was invented and patented by Slobodan M. Ćuk and Robert D. Middlebrook [108]. The non-isolated Ćuk converter can be modified to obtain the isolated version of the converter. This can further be modified to charge multiple batteries simultaneously, as shown in Figure 20. It provides an output voltage that is described by Equation (25), and the design [105] of the inductance and capacitance of the inductors and capacitors are calculated using Equations (34) through (39).

Figure 20.

Single-switch isolated Ćuk converter with ‘k’ number of secondary windings.

Considering the average value input current represented by Iin, the average conduction loss in the MOSFET Q [105] is given estimated using Equation (40).

The average switching loss of of the switch Q [105] can similarly be estimated using Equation (43).

where,

5.1.5. Single-Switch Multi-Output Isolated Zeta Converter

A Zeta converter is a modified buck-boost converter, and its isolated version uses one transformer, one inductor, one capacitor, one active switch, and one diode. An isolated Zeta converter is emerging as an attractive option for EV battery charging as it gives a very stable response and requires minimal control. The isolated zeta converter modified to charge multiple batteries is shown in Figure 21. The relationship between the output and input voltages is given by Equation (25). The inductance of the magnetizing inductance and the inductor is calculated using Equations (44) and (45), respectively. The capacitance of the capacitors and are given by Equations (46) and (47), respectively.

Figure 21.

Single-switch isolated zeta converter with ‘k’ number of secondary windings.

5.1.6. Single-Switch Multi-Output Isolated Buck (Fly-Buck) Converter

The single-switch fly-buck converter is shown in Figure 22 for multiple-battery charging. The converter has a capacitor across which the first output can be taken (shown across as a small battery of voltage . This can be used to charge the low-voltage auxiliary battery. The secondary windings can charge other batteries based on the transformer turns ratio. The equations for output voltages are given by Equations (48) and (49).

Figure 22.

Single-switch isolated fly-buck converter with ‘k’ number of secondary windings.

5.2. Two-Switch Isolated DC-DC Converters

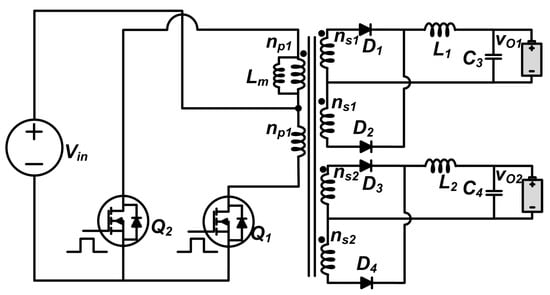

5.2.1. Two-Switch Flyback Converter

The two-switch flyback converter is used to overcome the typical problems of a single-switch flyback converter. The topology can be used for multi-battery charging, as shown in Figure 23. It can also be modified into a quasi-resonant flyback converter (a DCM Flyback having a valley switching turn on). The output voltage equation is the same as the flyback converter (Equation (2)). The same pulse is provided to both the switches of the converter. The two-switch flyback converter has better efficiency since the clamping losses are removed by recycling the leakage energy to the input side through the two diodes. This also implies reduced thermal stress on the switch. The overall voltage stress is divided between the two MOSFETs [109]. In this topology, the maximum duty cycle limitation is 0.5 when operating in continuous conduction mode [109].

Figure 23.

Two-switch flyback converter feeding ‘k’ number of batteries.

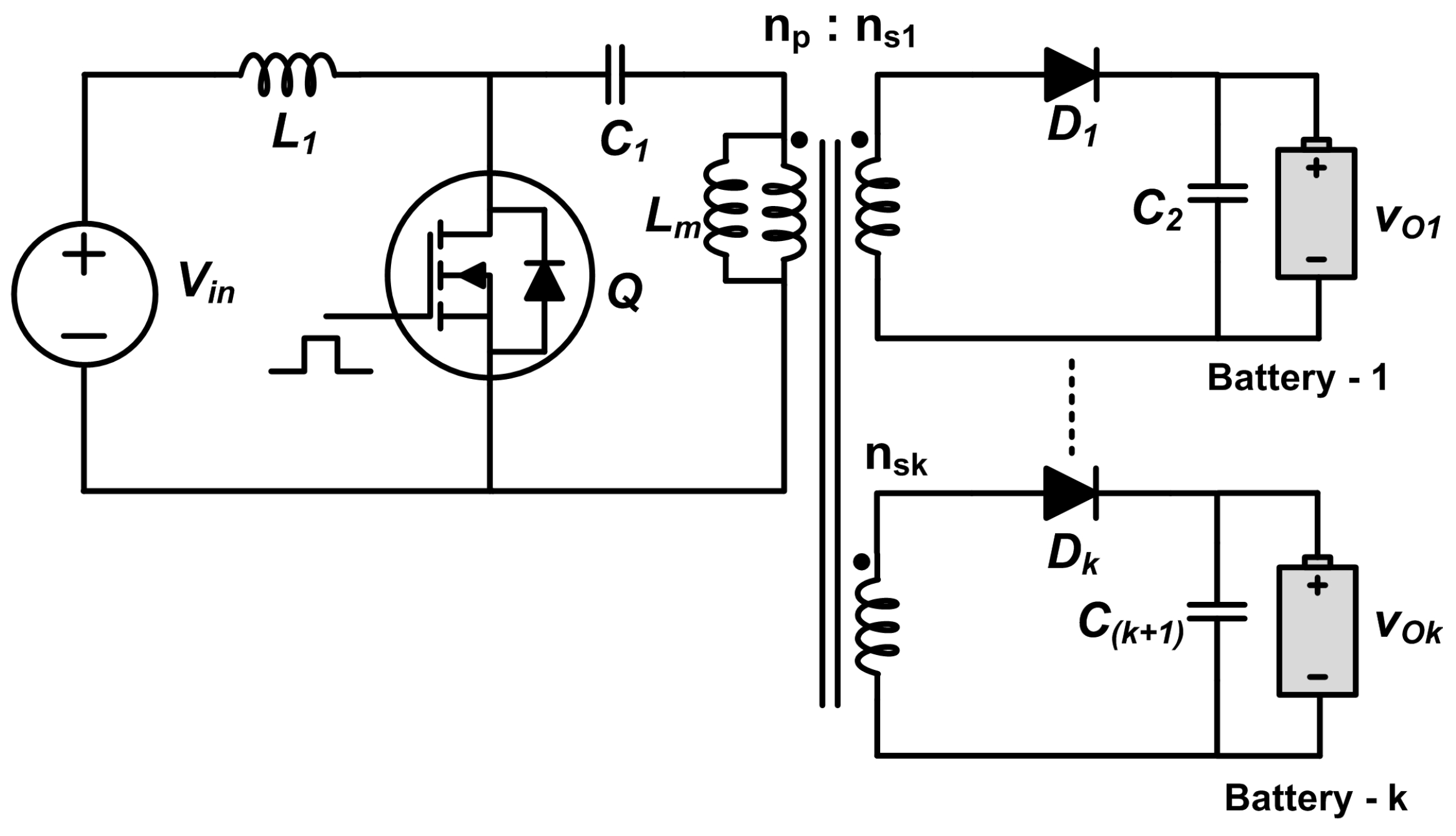

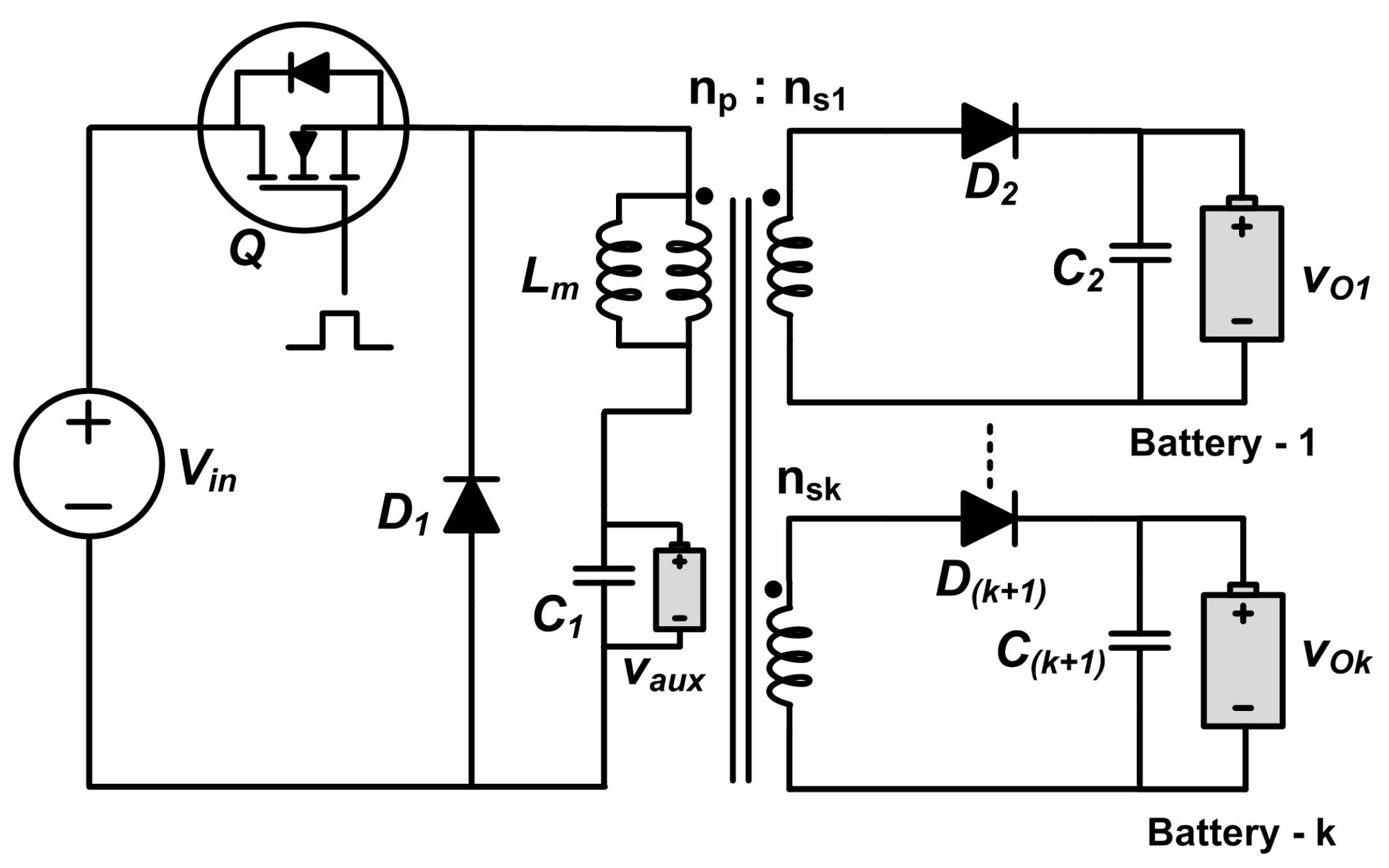

5.2.2. Two-Switch Forward Converter

The two-switch forward converter feeding multiple batteries is shown in Figure 24. The output voltage is given by Equation (50). It is usually used between 150 W and 750 W [110]. The circuit has multiple advantages, including no body-diode conduction, no snubber requirement, and the possibility of handling multiple isolated outputs. It does not require any dead-time and does not suffer from the problem of a potential shoot-through. However, the frequency of operation is limited due to its inability to switch at zero voltage [110] and requires a relatively larger transformer since it is a single-ended converter. The minimum value of inductance Lk is given by Equation (51), and the maximum value of the duty cycle is limited to 50% [111].

where IO,B is the output current at the CCM/DCM boundary, given by,

Figure 24.

Two-switch forward converter feeding ‘k’ number of batteries.

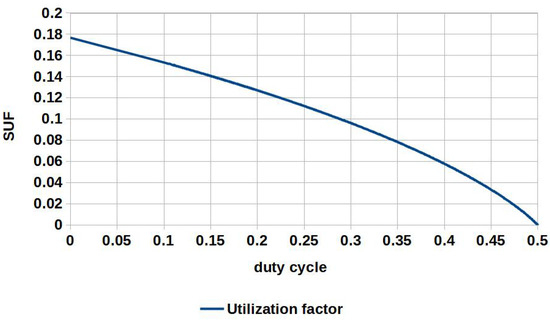

The semiconductor utilization factor () for the two-switch forward converter is given by Equation (53). The plot of duty cycle vs. for this converter is presented in Figure 25.

Figure 25.

Semiconductor utilization factor of the two-switch forward converter.

The conduction loss in the diode is given by Equation (54) and that in switch Q is given by Equation (55).

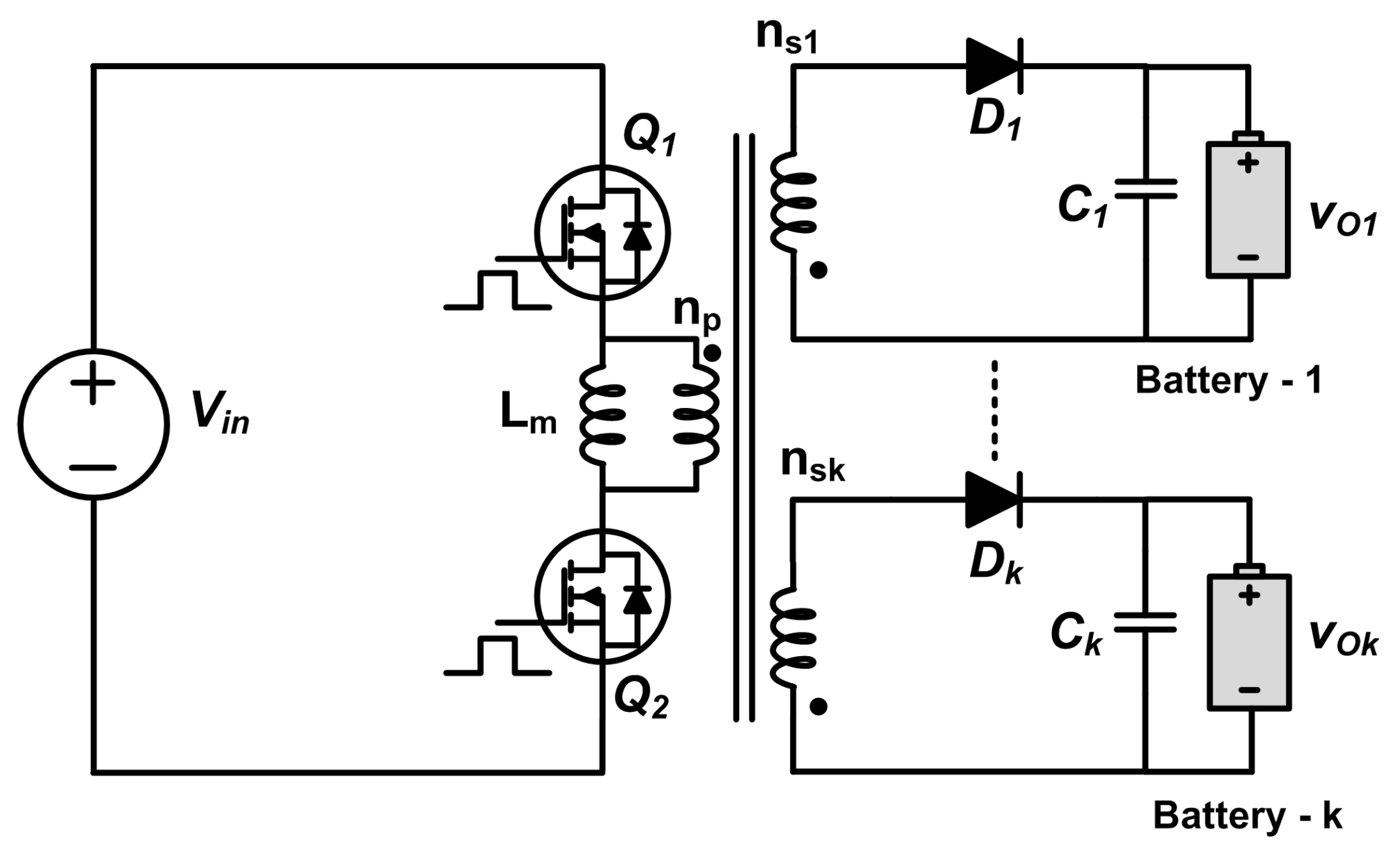

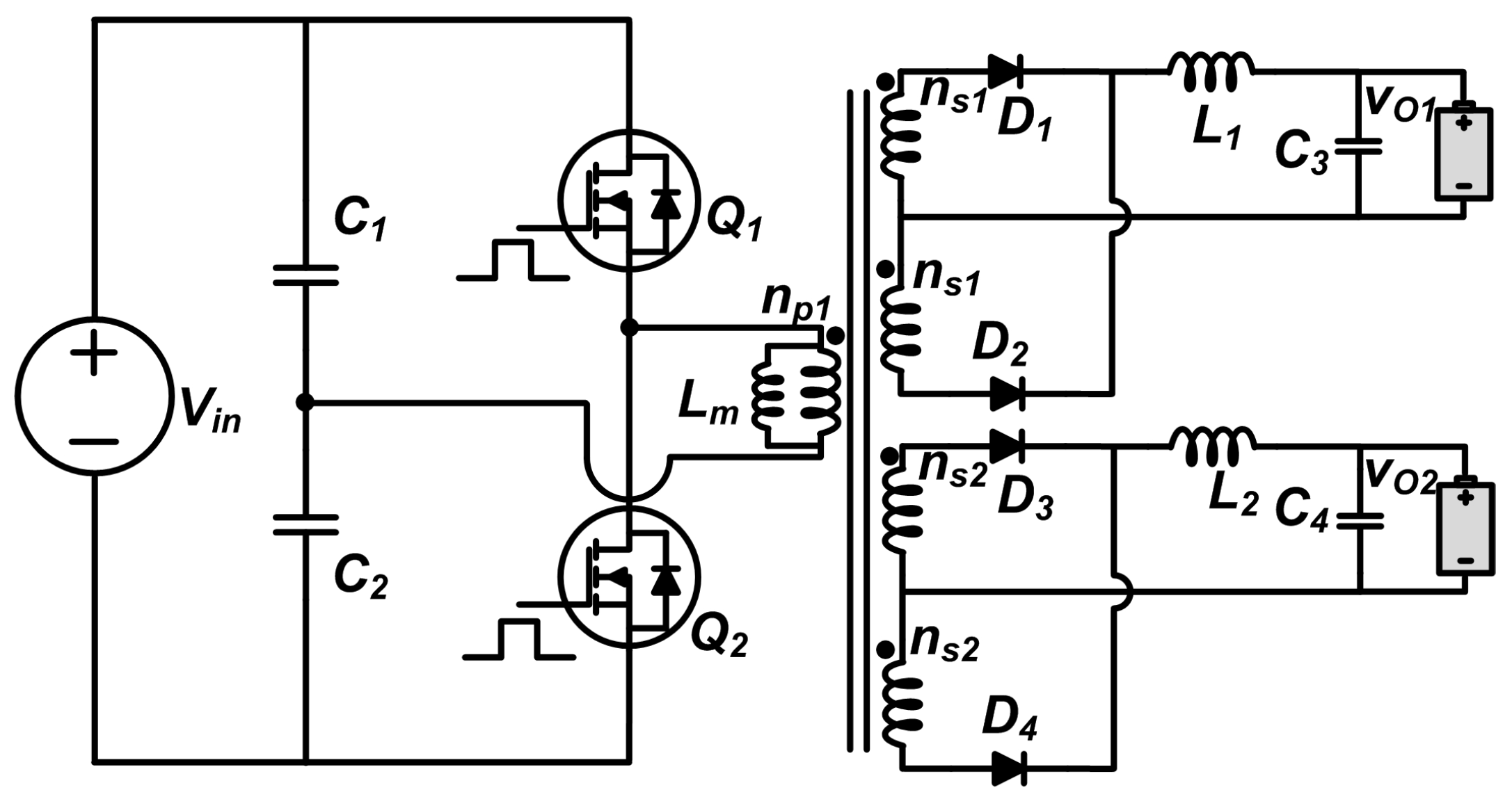

5.2.3. Push-Pull Converter

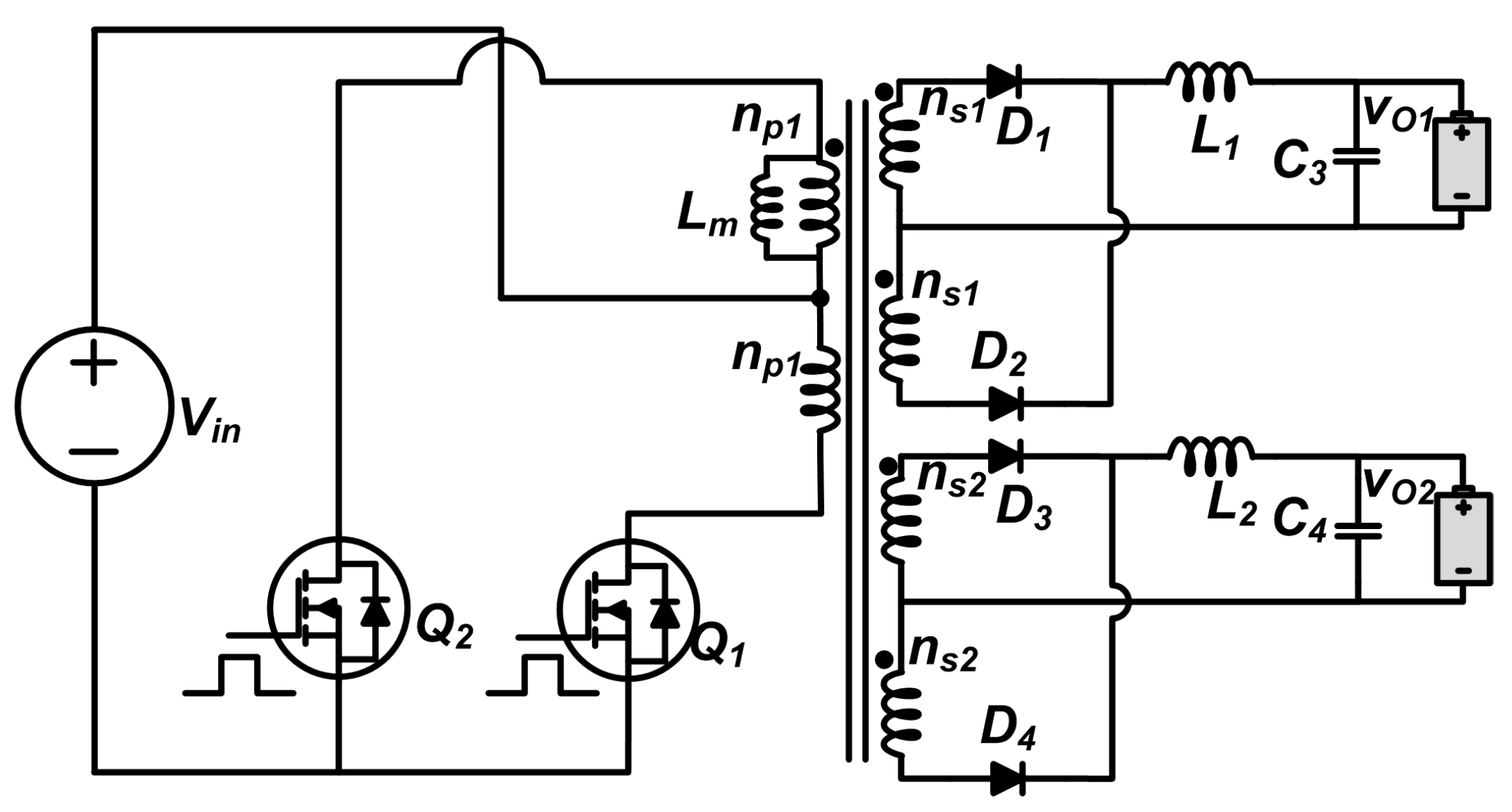

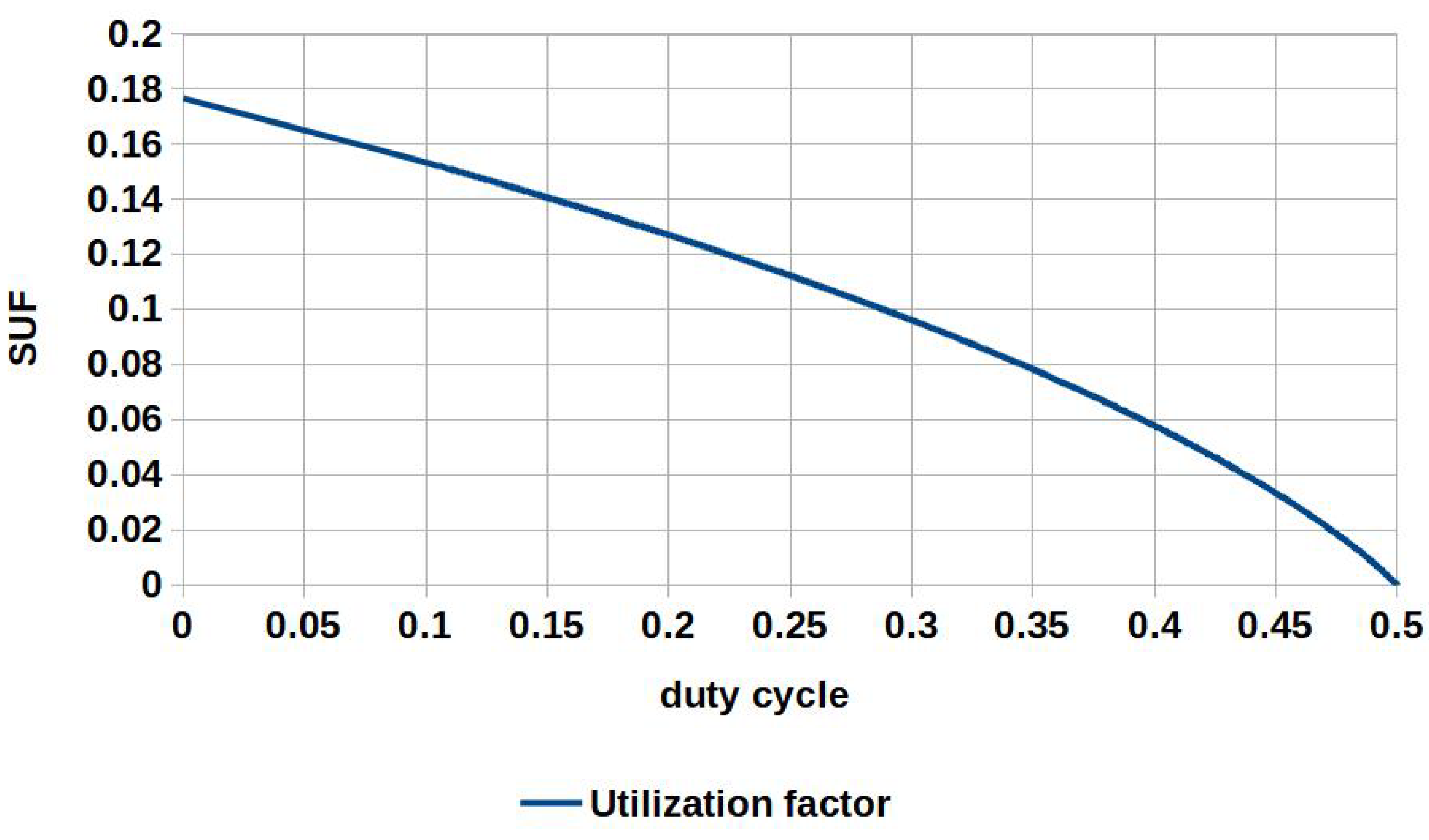

The push-pull topology is another isolated converter that can charge multiple batteries simultaneously. Figure 26 shows the push-pull converter topology used to charge two batteries. The output voltages of the push-pull converter feeding two batteries are given by Equations (61) and (62).

Figure 26.

Push-pull converter feeding two batteries.

The semiconductor utilization factor () for a push-pull converter is given by Equation (63), and a plot of duty cycle vs. is provided in Figure 27. From the equation of , it can be inferred that the SUF would be imaginary for duty cycles greater than 50%. Hence, % is the duty cycle limitation for a push-pull converter.

Figure 27.

Semiconductor utilization factor of a push-pull converter as a function of duty cycle.

The average value of conduction losses in switches and are estimated using Equations (64) and (65), respectively. Similarly, the average conduction losses in the diodes on the secondary side are estimated using Equations (66) and (67), respectively. We must note that the conduction loss in diodes and are equal and that in and are equal. Hence, the loss equations for and have been presented.

5.2.4. Current-Fed Push-Pull Converter

Texas Instruments design review [112] gives the details of the current-fed push-pull (CFPP) converter. It is also called a push-pull isolated boost converter [105]. It gives low-noise outputs with good efficiency. Instead of a center-tapped transformer secondary (CTTS), conventional push-pull and CFPP can use a diode bridge rectifier on the secondary side [105] to get similar outputs. The maximum duty cycle of the CFPP converter is limited to 50% [105]. The DC voltage gain is given by Equation (72). The input inductance and the magnetizing inductance Lm can be calculated using Equations (73) and (74), respectively.

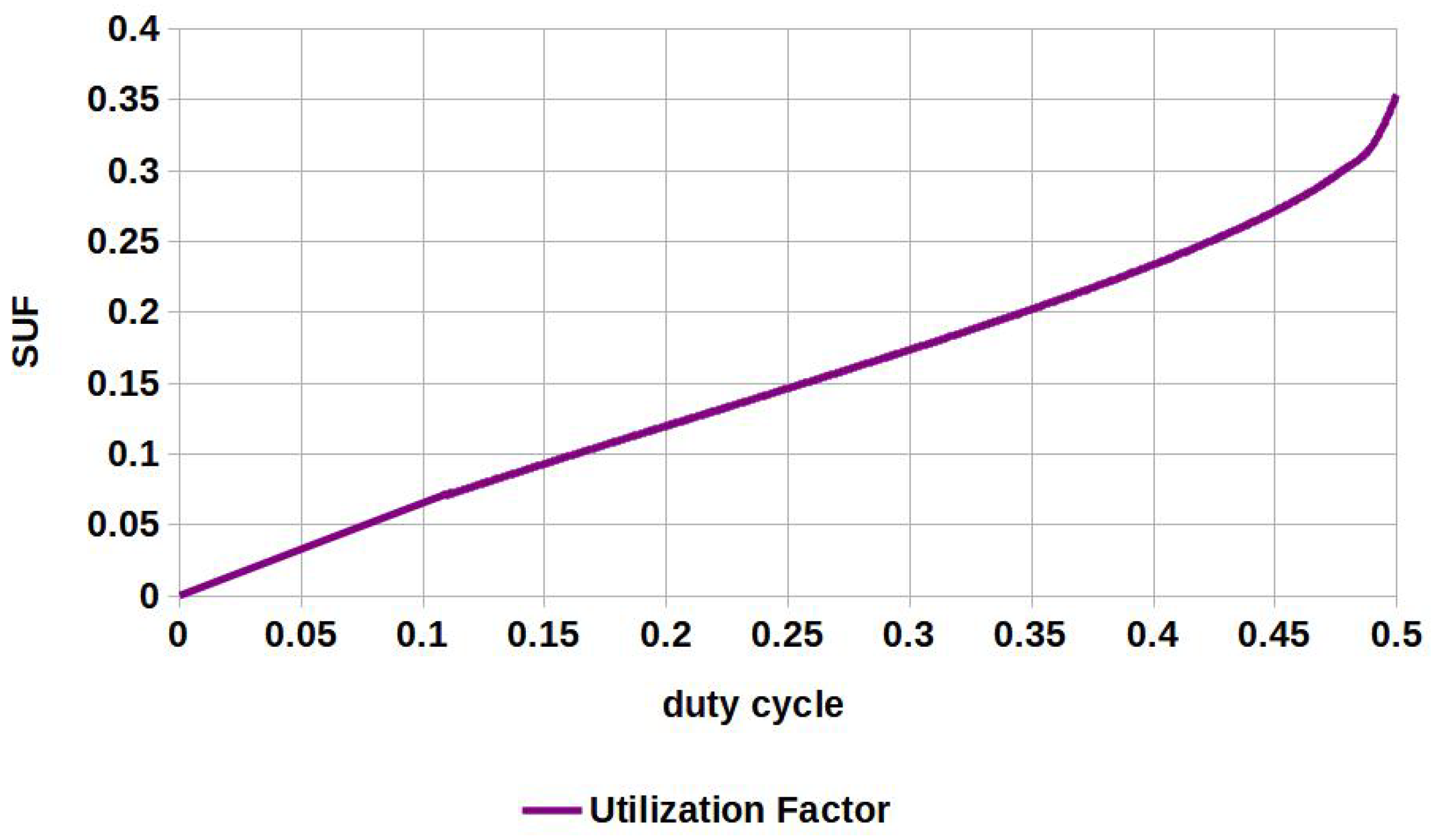

For the CFPP converter, the semiconductor utilization factor is given by Equation (77), and the corresponding plot of duty cycle vs. SUF is shown in Figure 28. From this curve, we can observe that the SUF is better at lower duty cycles. Thus, the transformer turns ratio must be chosen to ensure operation at high SUF.

Figure 28.

Semiconductor utilization factor of current-fed push-pull converter.

For loss estimation, we note that the average conduction losses of both switches are equal since they conduct the same average current. Similarly, the conduction losses in diodes and are equal, while the conduction losses in and are also equal. The conduction loss in switches and are estimated using Equation (78), that of diodes and is estimated using Equation (79), and that of diodes and is estimated using Equation (80).

The loss equality mentioned above also remains steady during switching losses. Thus, the average switching loss in switches and are estimated using Equation (81), that in diodes and using Equation (82), and that in and using Equation (83), respectively.

The gating circuit for the push-pull converter is relatively simple. The current-fed variant has lesser input current ripple and has no flux imbalance [113]. The major disadvantage of the push-pull topology is that the voltage stress across the MOSFETs is more than the input voltage magnitude [114].

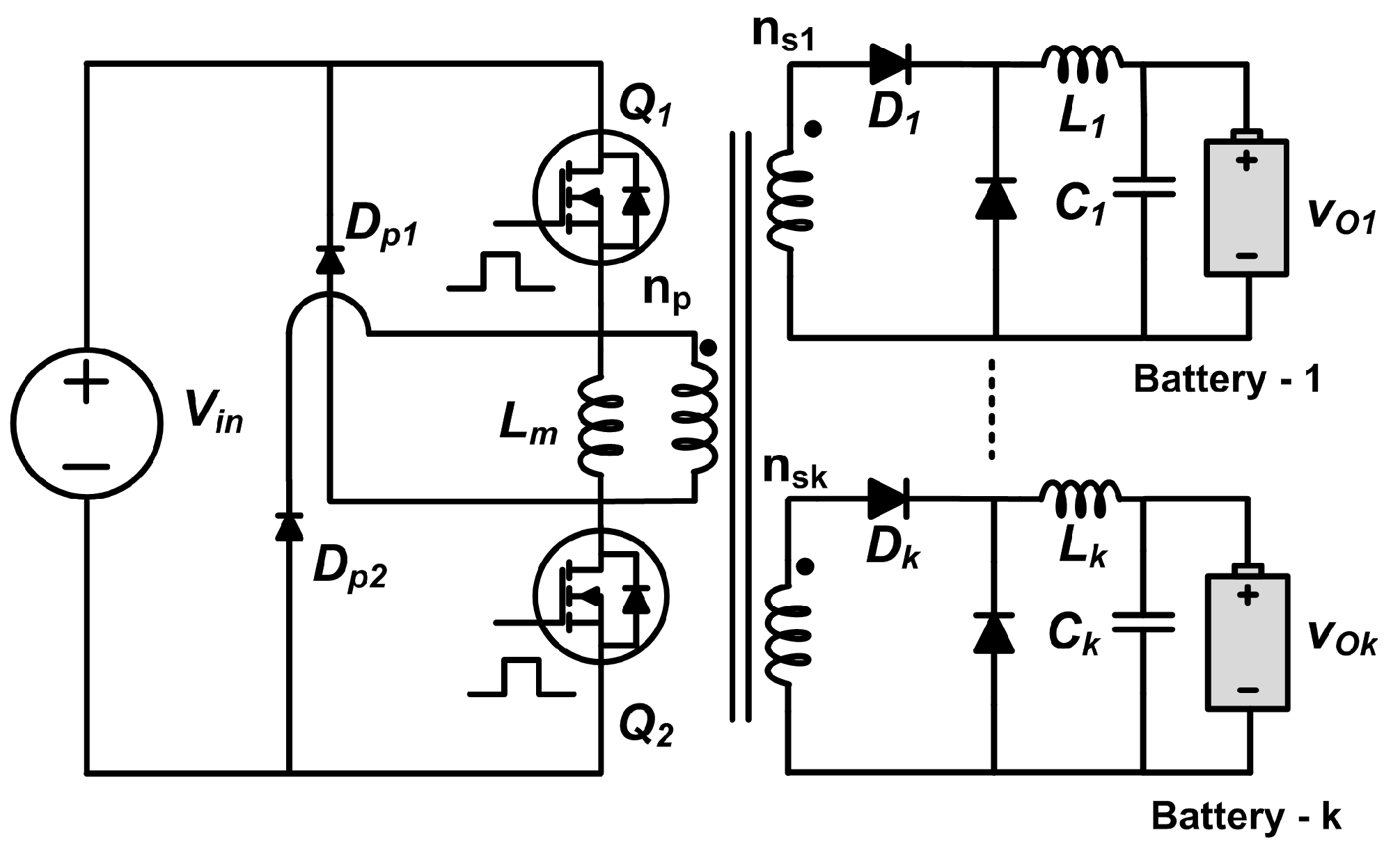

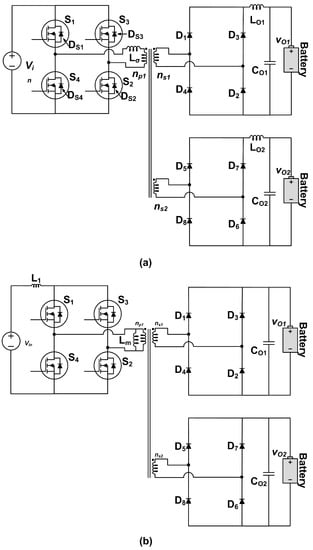

5.2.5. Active Clamp Forward Converter

The active clamp forward converter uses two switches. There are two possible topologies, as shown in Figure 29a,b. The primary difference between the two topologies is the placement of the clamping switch (). An N-Channel MOSFET is used in the high-side active clamp, while a P-Channel MOSFET is required for the low-side active clamp circuit. Due to this, the high-side clamp can be used for voltages higher than 500 V, while the low-side clamp is restricted for voltages below 500 V. The switch stress is (switch ). The high-side clamp can be used for offline applications, while the low-side is restricted to telecommunication applications. The output voltage as a function of the duty cycle [115] is given by Equation (84). The minimum inductance value of the transformer magnetizing inductor (Lm,min) and the output inductor (Lk,min) are given by Equations (85) and (86), respectively, and the minimum value of the capacitance of the output capacitor (Ck,min) is given by Equation (87) for the low-side active clamp configuration [116]. The N-MOSFET is selected based on the maximum drain-source voltage, the transformer primary’s peak current, and the MOSFET package’s maximum allowable power dissipation. In contrast, the P-MOSFET should be selected based on the maximum drain-source voltage [117]. For the high-side active clamp, the magnetizing inductance is proportional to the square of the primary turns [118], as shown in Equation (88).

Figure 29.

Two topologies of active clamp flyback converter: (a) high side active clamp (flyback clamp), and (b) low side active clamp (boost clamp).

5.3. Suitability for EV Battery Charging

The isolated converters described in Section 5.1 and Section 5.2 are converters where the energy transfer from the primary side to the secondary side depends on the energy stored in the magnetizing inductance () of the transformer during one-half of the switching cycle. In most high-frequency transformers, the order of will be in H. This implies that the energy () will be relatively low. Thus, these converters are preferred for low-power applications, usually between 100 and 500 W. In addition, the output voltage level is also limited. These converters can be used for charging batteries of low-power and low-voltage. The present trend for electric cars and electric buses is to use battery voltages of 400 V or 800 V since the current will be lower at these voltages, giving lower losses. The single- and two-switch converters are not very suited for such applications. For high-power applications, the energy transfer should not depend on stored energy in the magnetizing inductance of the transformer. Such converters use the full-bridge or its variant topology with the appropriate transformer. In these circuits, the transformer is not used to store energy but only for step-up/down action and isolation. These circuits are most suitable for high-power applications and are described in Section 5.4. These converters can be used for high-power, high-voltage battery charging and can be employed for fast charging stations. Among these, the resonant converters and phase-shifted full bridge variant topologies are best suited for fast and ultra-fast charging [44,119,120,121].

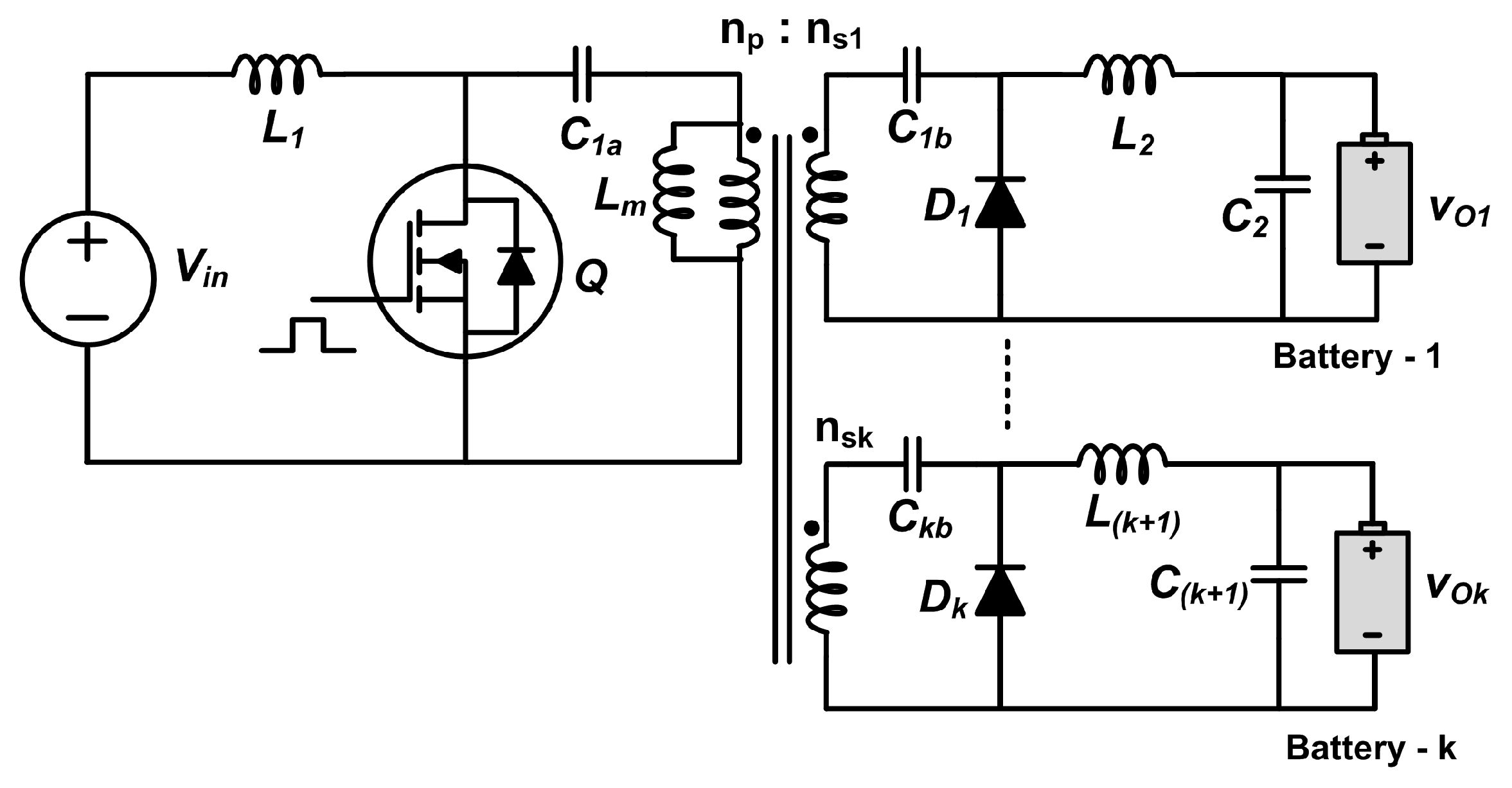

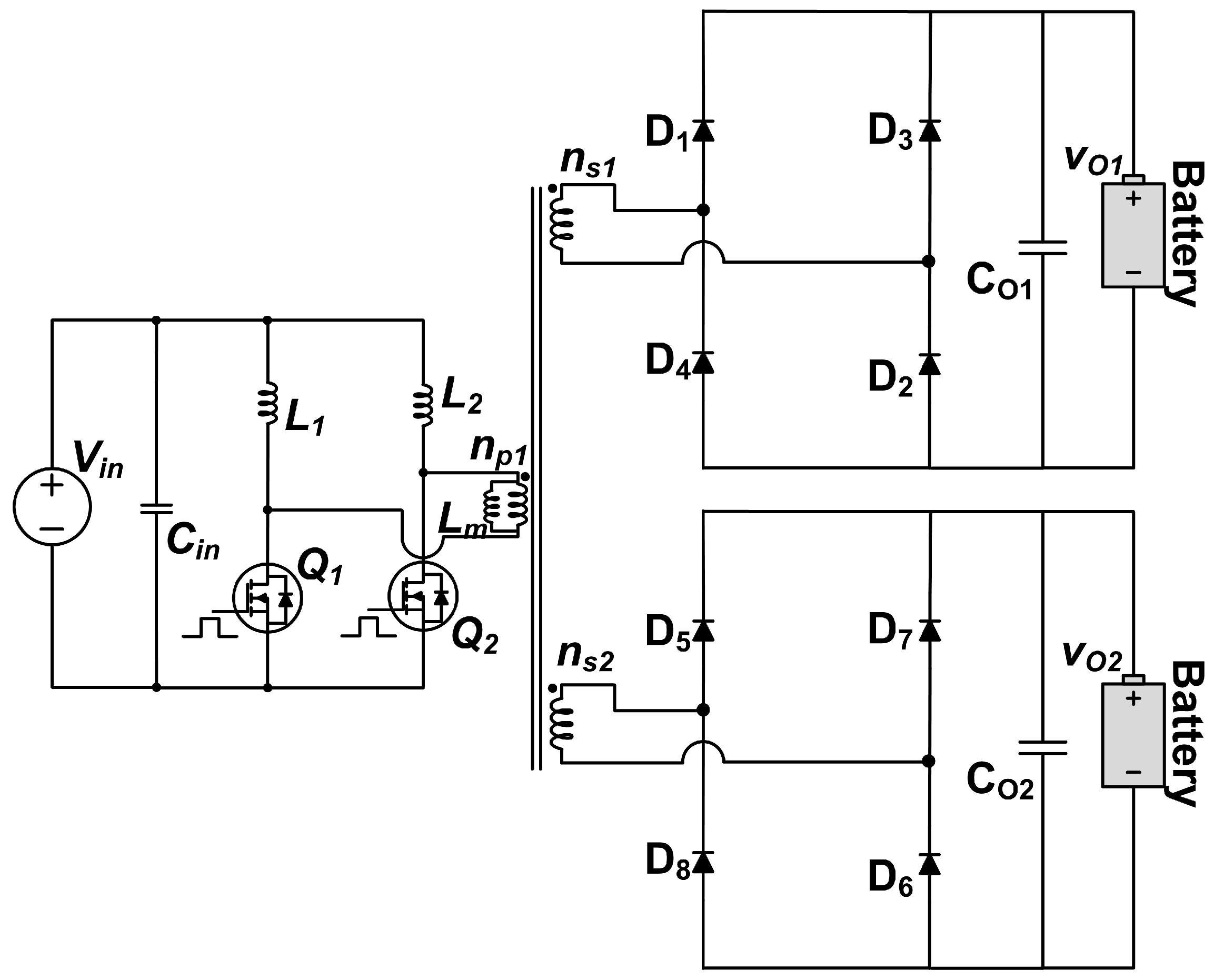

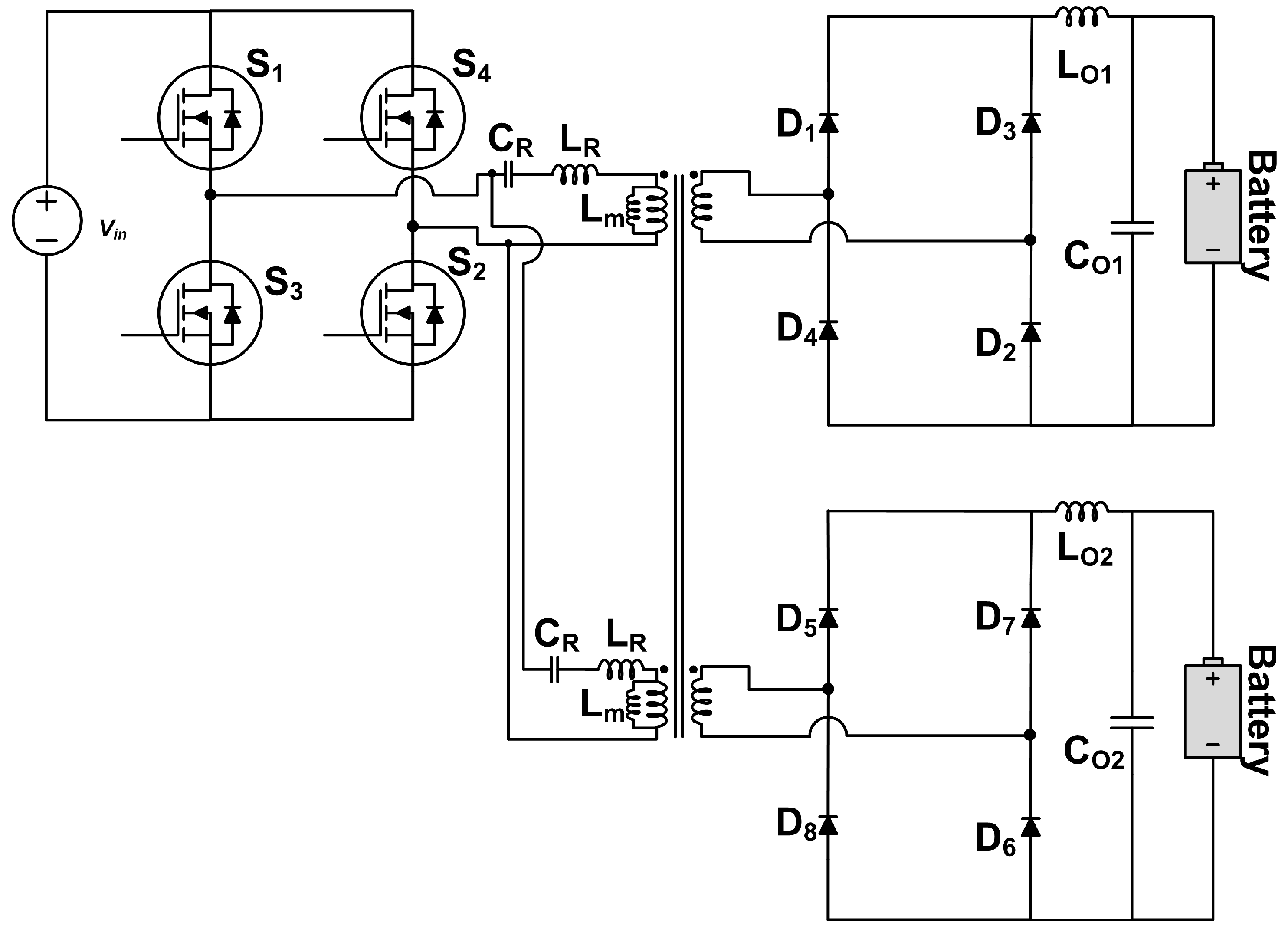

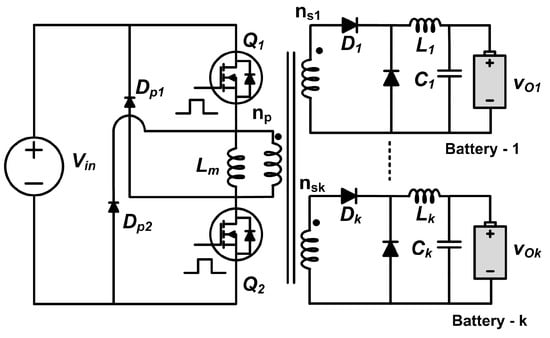

5.4. Bridge-Type Isolated DC-DC Converters

5.4.1. Half-Bridge Converter

The half-bridge converter is one of the simplest bridge-type DC-DC converters and can be used for battery charging applications. Shivaprasad et al. [122] have proposed a half-bridge converter for charging one battery. The system proposed is used to charge a 48 V battery from 180–270 V input source. The pulses for the switches are generated using TL494 pulse width modulator (PWM) integrated circuit (IC). The circuit can be modified to charge multiple batteries to obtain the circuit diagram of the half-bridge converter feeding two batteries, as shown in Figure 30. The relationship between input and output voltages is given by Equations (89) and (90). Compared with the push-pull topology, the voltage stress across the MOSFETs in half-bridge topology is lesser than the input voltage. Compared with the isolated SEPIC and Ćuk topologies, the half-bridge configuration has lower conduction and switching losses, leading to better efficiency. Similar to the push-pull converter described in the previous subsection, the half-bridge converter duty cycle is limited to 50%. In addition, the center-tapped configuration can be replaced by a diode bridge rectifier [105].

Figure 30.

A half-bridge converter feeding two batteries.

The magnetizing inductance can be calculated using Equation (91), and the output inductance can be calculated using Equations (92) and (93), respectively. The capacitance input side capacitors are usually equal and can be calculated using Equation (94). The capacitance output side capacitors can be calculated using Equation (95).

where and is the time period of conduction of the switch.

For a half-bridge converter, the semiconductor utilization factor is the same as that of the push-pull converter and is given by Equation (63) with its plot in Figure 27. The average value of conduction losses in switches and are the same, and they can be estimated using Equation (96). Similarly, the average value of conduction losses in diodes and are the same (Equation (97)), and those in and are the same (Equation (98)).

The average value of switching losses of switches and are the same and can be estimated using by Equations (99) and (100), respectively.

The average value of switching losses of diodes and are estimated using Equations (101) and (102), respectively.

A modified half-bridge converter was proposed by Ou et al. [123]. It uses eight diodes, two switches, three capacitors, and two inductors, and a center-tapped transformer. This can be modified to charge two batteries (or more) by using transformers with multiple secondaries. The ratings of the primary side components become critical in such a case. Hyeon and Cho [124] have proposed a dual half-bridge LLC Resonant Converter with two outputs (one main output and one sub-output). This could also be used for battery charging applications, with the main output used to charge the main battery and the sub-output used to charge the auxiliary battery. Li and Zhang [125] have proposed a modified system called the isolated voltage type half-bridge three-port converter. It comprises three input combined half-bridge circuits with a three-winding transformer.

Jain et al. [126] have proposed a bi-directional topology with a half-bridge converter on the primary side and a current-fed push-pull on the secondary side to charge one battery, albeit for low-power applications. This can be extended to charge multiple batteries simultaneously.

5.4.2. Half-Bridge Isolated Boost Converter

A half-bridge isolated boost (HBIB) converter is a boost-derived converter [105] that uses two switches on the primary of the HFT and a diode bridge on the secondary in its basic topological format. Such a converter can feed two batteries of equal rating and is shown in Figure 31. Equation (103) gives the relationship between the input and output voltages.

Figure 31.

Half-bridge isolated boost converter.

The maximum duty cycle of the converter is limited to 50%. The inductance of the inductors , , and can be calculated using Equations (104), (105) and (106), respectively. Similarly, the capacitance of the output capacitors and can be found using Equations (107) and (108), respectively. The capacitance of the input capacitor can be calculated using Equation (109).

The semiconductor utilization factor () of the HBIB converter is given by Equation (110), and the plot of the as a function of the duty cycle is given in Figure 32. It can be seen that the is better at lower duty cycles. Thus, the transformer turns ratio must be selected such that the converter operates at a duty cycle close to 50% [105].

Figure 32.