Abstract

The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda is known for its holistic and global dimension, as demonstrated by the saying “no one left behind”. However, local governments still struggle to take tangible actions and to reallocate resources for implementing Sustainability Strategies. With the aim to improve multi-level governance for sustainable development with complex and cross-sectoral policies, the research investigates how much Regional Sustainable Development Strategies (RSDS) and public authorities’ structures are mutually consistent. Starting from the existing governance framework at the regional and local levels (Province and Metropolitan City), the study analyzes: the organizational structures/functions of the public institutions and the integration between their competences and the RSDS targets. The case study is the Lombardy Region in Italy. The analyses were conducted through a review of key legislations and regulations, and the introduction of a homogeneous reading grid that identifies the principal “Invariant Functional Macro Areas” (IFMA) of local authorities. The paper highlights the structural weakness in implementing and localizing EU strategic Agendas and examines the extent to which public offices are currently structured to adequately address the RSDS challenges. The research shows how sectoral fragmentation of competence can collide with the holistic layout of sustainability: new integrated approaches are needed to strengthen cross-sectoral dialogue and cooperation within and between public institutional bodies.

1. Introduction

Despite the spread of multiple frameworks focused on climate change, such as the United Nations’ (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and the clear relevance of the local level in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), territorial governance for sustainability still struggles to take tangible actions that consider the holistic interactions between climate, environment and society.

The UN 2030 Agenda explicitly refers to the international, national and regional entities [1,2], so that many high-level coordination groups and sustainable development councils were established. As a result, the international targets of sustainability have been declined both at the national and regional scales, through the National and Regional Sustainable Development Strategies (NSDS and RSDS). However, the importance of the SDGs’ localization at the city level has been expressed by the ONU 2030 Agenda itself (Goal 11) and by the environmental legislation (i.e., the Italian Environmental Code, Law 152/2006, article 34) so that local governments are recognized to be crucial to the SDGs successful implementation [2,3,4,5]; also, because more than 65% of the SDGs directly concern local communities and the administrative decentralization of functions is currently in place in many countries [6]. Despite this, it is less understood how local governments should reallocate resources to take concrete actions [1,4,7].

In the Italian context, existing central coordination structures for sustainable development are represented by inter-ministerial committees, such as the Inter-ministerial Committees for Ecological Transition (CITE) and for Economic Programming and Sustainable Development (CIPESS). Their work and the complex consultation process with central administrations, the Regions, civil society and the world of research and knowledge have led to the definition of the NSDS and various RSDSs as well.

The Italian NSDS was presented to the Council of Ministers on October 2017 and approved by the Inter-ministerial Committee for Economic Programming (CIPE) in December 2017 [8]. Several RSDSs, however, have not been approved by all Italian Regions. The Italian Voluntary National Review (VNR) reported that by April 2022, only 11 out of 21 Regions (19 Regions and two autonomous Provinces with regional powers) had concluded the process of approval [9]; the RSDS of Veneto was the first to be adopted in July 2020, followed by that of Liguria (January 2021) and Lombardy (June 2021). After the VNR detection, the last RSDSs approved are those of Molise and Piemonte in July 2022; hence, currently, the total RSDSs approved are 13, while the remaining eight Regional Strategies are still in the phase of definition.

As the NSDS is becoming a reference for the definition of the territorial sustainable development strategies, thanks to the dialogue roundtables with Regions and Autonomous Provinces [10], similarly, the RSDS may represent the reference for Provinces and Municipalities to define their programs and to establish cross-departmental working groups aimed at achieving sustainability targets.

However, different studies reported that multiple factors hinder the implementation of these strategies, as well as the integration of sustainability targets in local policies, such as: (i) the instability and overlapping of government mandates, that results in policy fragmentation and administrative reconfiguration [2]; (ii) the absence of clear responsibilities and resources (for personnel and programs) devolved to local authorities [2,5]; and (iii) the low cross-government coordination of public administrations, which must be strengthened in all central and local authorities [4,5,6,10,11].

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Ministry for Ecological Transition (MiTE, recently renamed to the Ministry of Environment and Energetic Security, MASE), during the project of revisioning of the Italian NSDS, identified priorities areas for building capacities and governance processes to enhance sustainable development. In particular, the OECD Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (PCSD) recommendations indicate a need for institutional mechanisms that: (i) enable long-term and strategic planning and visioning, (ii) address policy interactions across sectors and (iii) align actions between levels of government [10].

Since there is awareness of the poor ability of local administrations in addressing environmental policies, i.e., managing complex procedures, communicating and cooperating between structures [12], it seems to be necessary to strengthen both the administrative capacity and resources (in terms of time, energy and financial resources) [4,5,6]. Indeed, the decentralizing responsibility for implementing the SDGs at local levels of government may require the creation of additional structures [3], such as a sustainability department or a strategic coordination unit with sufficient cross-sectoral mandates and powers [4]. This effort would help to implement multi-level governance across many levels, scales and sectors, to deal with holistic and integrated challenges [1,2,11,13], and to improve the coordination across siloed city departments [4,6].

In Italy, the multi-level dialogue and coordination between Regions and local administrations (i.e., Municipalities) vary significantly across the country. Trying to implement a cross-sectoral approach to reach strategic targets for sustainability, many Italian cities and Regions face barriers related to their highly sectoral organizational structure, the so-called “in silos” structure [10].

Considering that the territorial governance in Italy is often based on the principle of subsidiarity of functions, that commonly involves decisions taken at different levels, the complexity of multi-level coordination becomes exponential. In fact, Italy presents a four-level government: national, regional (19 Regions and two autonomous Provinces with regional powers), provincial (107 supra-municipal territorial units out of which 14 acquired the status of Metropolitan Cities in 2015, 83 are Provinces, six are free consortia of municipalities and four are non-administrative unites, i.e., ex-provinces) and local (7904 Municipalities) [14]. Therefore, the principle of subsidiarity implies that public functions must be performed at the local level of Municipalities, the closest level to the citizens, but simultaneously, it must be referenced to higher and unitarian levels of power and coordination, that is the provincial or regional level. The regional authority can legislate in certain areas (of concurrent competence State–Region, such as town planning) and thus, the application of the subsidiarity principle can be diversified.

In the case study of this research, the Lombardy Region, the principle of subsidiarity of functions has been strongly emphasized as a fundamental criterion for the management of the territory (article 1, paragraphs 2 and 3, Regional Law 12/2005), through which the Region regulates spatial planning activities and defines planning guidelines to ensure sustainable development processes. In the Lombardy Region, the number of territorial and local authorities amount to 1506 Municipalities grouped in the followed 12 Provinces, out of which one is the Metropolitan City of Milan: Bergamo, Brescia, Como, Cremona, Lecco, Lodi, Mantova, Monza e Brianza, Pavia, Sondrio and Varese [14]. The choice of the present contribution to consider the Lombardy Region as a case study is supported by multiple motivations: (i) it is the first region of Italy by economic importance, contributing to about a fifth of the national GDP [15]; (ii) it hosts many of the country’s largest industrial, commercial and financial activities, becoming one of the most industrialized areas of Europe and reaching a per capita income that exceed the European average of 35% [15]; (ii) its population amounts to around 9.9 million inhabitants (9,981,554 in 2021) [16] in an area of around 23,864 km2 [17], becoming the first Italian region for resident population and overcoming the European average of population density (435.8 inhabitants/km2 in 2019, compared to the European 109 inhabitants/km2) [18,19]. Furthermore, despite the fact that Lombardy is the Italian region with the largest area of consumed soil (289,386.15 ha in 2021) [20], it has already adopted an important law for land use containment (Regional Law n.31/2014).

To delve deeper into the case study, the Lombardy Region has launched its path towards the localization of the ONU 2030 Agenda since 2019, starting with the signature of the “Lombardy Protocol for Sustainable Development” (presented in New York at the SDGs Summit of the United Nations on the 24–25 September). Later, the Lombardy Region has adopted its Regional Sustainable Development Strategies (Strategia Regionale di Sviluppo Sostenibile) (in acronymous SRSvS) in June 2020 (approved with the DGR n.4967/2021) and, subsequently, its updates have been published in October 2021 and in June 2022. The SRSvS is structured in five Strategic Macro Areas (SMA) that embrace all the pillars of sustainability, addressing both environmental, social and economic issues, that institutions and all the regional system have committed to achieve (Lombardy Region, 2022):

- SMA 1.

- Health, equality, inclusion;

- SMA 2.

- Education, training, work;

- SMA 3.

- Development and innovation, city, territory and infrastructure;

- SMA 4.

- Mitigation of climate change, energy, production and consumption;

- SMA 5.

- Eco-landscape system, adaptation, agriculture.

Each SMA is then declined in multiple Areas of Intervention (AI) and Strategic Objectives, to which quantitative targets and set of indicators are assigned. In order to monitor progress and implement the UN 2030 Agenda through local initiatives, the Lombardy Region has presented its own Voluntary Local Review (VLR), attached to the Italian Voluntary National Review (VNR), at the High-Level Political Forum in July 2022 [21].

In order to improve multi-level governance for sustainable development, the research wonders if public authorities possess the adequate administrative capacities and resources to implement their Sustainable Development Strategy and how much strategy and structure for its realization are mutually consistent. Starting from the current organization of territorial and local authorities, a review of their competences is proposed through the analysis of the RSDS’ main topics and targets.

The primary aim of the study is to verify if territorial and local authorities (i.e., Provinces and Metropolitan Cities) are prepared to deal with complex and cross-sectoral policies in order to locally implement all the sustainability dimensions (i.e., environmental, social and economic issues). In other words, this contribution investigates how strong the integration between the public sector’s organizational structure and the RSDS targets is. As previously mentioned, the research is applied on the case study of the Lombardy Region.

The purpose of this contribution has been structured in three chained research questions according to which the following analyses have been organized:

- What are the main functional areas of competence of local authorities?

- How are competences coordinated within different levels of government?

- Are authorities’ competences coherent with the RSDS targets?

From the literary review on Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar, precedent studies highlighted that despite occasional reference to the SDGs in strategic and operational plans, there is a lack of explicit sustainability programs that include clear management responsibilities [6]. Many studies refer to the SDGs implementation and policies integration [10]: some introduce the role of local authorities and identify general barriers and opportunities to shape local action for sustainable development, with a focus on municipalities [1,2,5] or on the wider concept of governance for sustainability [3,13]; other research analyzes the extent to which strategic plans encompass the sustainability paradigm [6]; and others apply a strategic management lens to local government sustainability activities, trying to understand positive and negative experiences from the process of SDGs localization [4] and to understand how and when investments in new capabilities are suitable for meeting sustainability goals [7]. Therefore, this literature review allowed the identification of a research gap, since no sources explicitly refer to how local authorities manage sustainable development goals by discussing their internal organizational structure and competencies. Soberón et Al. (2020) proposed an analysis for identifying the sustainability competences attributed to the organizational structure of the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food and Environment (MAPAMA) and for measure, its potential contribution upon each SDG target [11]; however, this study was conducted at the national level, not taking into account the local scale, nor the sub-national sustainability strategies that are the focus of this contribution. On the other hand, Medeiros and van der Zwet (2020) examined the design and implementation process of Integrated Strategies for Sustainable Urban Development (ISUD) at the metropolitan and medium-sized cities levels, highlighting how urban strategies can be strengthened through the creation of “intra/inter-city networks” and the active involvement of citizens and stakeholders. In particular, metropolitan areas seem to have more dedicated and operational urban planning structures with adequate resources (budgets and personnel) compared to medium-sized urban areas [22]; however, the study refers to horizontal governance and networks, instead of vertical governance and internal competencies of different institutional levels (that is the subject of this research). Moreover, Yang and Zhao (2022) analyzed, on the scale of megacities, the effect of different space governance tools and strategies on the spatial evolution of suburban forms, in order to achieve coordinated and sustainable development [23]. Nevertheless, here, governance tools are meant as plans and policies instead of institutions’ structures, responsibilities and capacities.

The literature analysis thus highlights two gaps:

- There are studies on sustainable development strategies at the municipal (city) or national level with a horizontal governance approach, but there are no such studies on vertical governance at regional and sub-regional levels (wide area) yet.

- There are no analyses that directly report the Sustainable Development Strategies and the structures of the regional and sub-regional authorities that have to implement them (Respecting the UN 2030 Agenda principle that no one is left behind).

The strengths of this research can therefore be summarized as follows. Making explicit what responsibilities different departments or sectors have, as well as developing a common language, can enable cross-sectoral dialogue and action, and enhance local authority’s cohesion and efficiency in reaching sustainability targets [2]. Consolidating strategies for sustainable development within public authorities would help to improve territorial governance solutions for climate-adaptive decision-making, through better internal organization (i.e., between levels of administration) and stronger inter-institutional collaboration. The definition of a governance system capable of guaranteeing inter-sectoral links and dialogue between the several competences involved is a key tool for coordinating targets and actions relating to all dimensions of sustainability (environmental, economic and social) [9].

Addressing the research questions, the principal findings of the study highlight that: (i) sustainability targets should become a horizontal priority above different sectoral policies; (ii) an “integrated” approach is needed to better link different policy goals across the social, environmental and economic fields; and (iii) the organizational structure of the local public authorities should be less sectoral and more in line with the Sustainable Development Strategy.

The article is organized into four sections. After the introduction, Section 2 describes the methodological approach, the main methods, data and tools used for the analysis of territorial and local public authorities, as well as their application to the case study. Section 3 presents the results of the case study of the Lombardy Region in a three-step analysis that addresses the three research questions:

- the comparison of local authorities’ internal organization, using a homogeneous reading grid (Section 3.1);

- the areas of competence among different levels of government (Section 3.2);

- the coherence of authorities’ competences with the RSDS targets (Section 3.3).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

The methodological approach used in the research was structured in multiple phases, in accordance with the three research questions addressed by the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological approach.

Firstly, the study started collecting and analyzing information about territorial and local authorities, their internal organization and competences (Section 3.1) on the base of the current governance framework. To achieve this task, multiple sources (i.e., official Statutes, Regulations and institutional portals) allowed the collection of much data. Table 1 summarizes the main categories in which information was organized to create a comprehensive and homogeneous database on how institutions operate. More details on sources are shown in Appendix A. The output of this cataloguing of information constitutes the cognitive basis from which the successive analyses were developed.

Table 1.

Database categories on how institutions operate.

Due to the complexity of different internal organizations of local authorities, a joint reading grid, self-developed, that identifies the principal functions of public bodies called “Invariant Functional Macro Areas” (IFMA) was defined.

The second phase concerned the comparison among the organizational structures and functions of the local authorities (Section 3.2) by applying the IFMA reading grid. The outcome of the second analysis consists in the identification of the different capacity gaps related to the RSDS implementation. The study refers to the organizational capacity, that means the degree to which the departmental structures (such as sectors and offices) and their staff are in place within the institutions and dialogue to develop and deliver sustainability policies. Implementing sustainability strategies requires a better alignment and coherence between institutional areas of competence and key strategic targets of RSDS. In this sense, the third phase of the study focused on the integration between institutional functions and the RSDS targets (Section 3.3).

The last phase wishes to identify potential solutions that will secure a high degree of institutional coordination to RDSD implementation.

The analyses have been performed with the introduction of a reading grid that identifies the principal “Invariant Functional Macro Areas” (IFMA); this tool is necessary to compare multiple structures and functions with those of the other institutions (i.e., Region, Provinces and Metropolitan City) in a homogeneous way. The introduction of classification methodology constitutes a necessary step, because of the difficulties encountered in collecting information on local authorities in several institutional portals (each authority has its own digital portal, organizational and functional charts).

The definition of the IFMA reading grid will be explained in the following paragraph.

The “Invariant Functional Macro Areas” (IFMA) Reading Grid

In order to conduct the comparison between the organizational structures and functions of the different local authorities considered, a homogeneous reading grid was introduced. The “Invariant Functional Macro Areas” (IFMA) (Table 2) has been set up for grouping multiple structures and functions in cross-cutting thematic areas of competence, comparable with the structures of other levels of government (i.e., Region, Provinces and the Metropolitan City). In this way, the IFMA classification allowed the interpretation of different areas, sectors, operational units, services, etc., in which the local authorities are organized, according to the same reading grid.

Table 2.

Invariant Functional Macro Areas (IFMA) (self-produced).

By reorganizing the internal structures of the Region, the Metropolitan City and the different Provinces through the IFMA reading grid, it is possible to understand which inter-institutional collaborations should be strengthened to improve vertical governance between different levels of government.

2.2. Materials

The main sources used in the research were the institutional portals of the local authorities of the case study, in order to understand the current hierarchical relationship between local bodies and investigate their internal organization and competences. Data were collected through the consultation of multiple sources: official Statutes, Regulations of the offices and services, organizational charts, functional charts and other official information available on the institutional portals of each of the public authorities, as shown in Table 1.

In the case study, the authorities considered were the Lombardy Region, its 11 Provinces and the Metropolitan City of Milan (a regional body and 12 sub-regional bodies) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Lombardy Region, its Provinces and the Metropolitan City of Milan.

The following paragraphs, Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2.2 and Section 2.2.3, will expose the current governance framework with basic data (what it is, what its general roles are, how its main organizational units are structured) relating to the Region, the Provinces and the Metropolitan City, in the specific case of the Lombardy Region, without which it is not possible to carry out and understand the subsequent analysis.

In order to understand how the principle of subsidiarity—vertical subsidiarity, which means distribution of administrative powers between different levels of territorial government—characterizes territorial management, a review of key legislation was necessary. The outcome of this step was, for each authority, a description of its role within the regional hierarchical structure (i.e., the vertical integration between institutions).

2.2.1. The Regional Level: Lombardy Region

The Region is an autonomous territorial authority that has its own Statute, specific powers and administrative functions that require a unitary exercise (article 114, title V, Constitution of the Italian Republic). The legislative powers of the Italian Regions result from the “concurrent power” between Regions and the State and, indirectly, from the non-exclusive power of the State, as defined by the Constitution of the Italian Republic (article 117, third paragraph, title V). Other functions of local interest are delegated to Municipalities, Provinces and Metropolitan Cities, in compliance with the principles of subsidiarity, differentiation and adequacy (article 4, paragraphs 1 and 2, Regional Law Statutory n.1 of 30 August 2008). This decentralization of powers thus allows the direct participation of local authorities in the administrative functions of the territory, improving the ability to meet citizens’ needs.

Despite the possible changes related to the Regional Council mandate, the organizational structure of the Lombardy Region is sufficiently consolidated in relation to their areas of competence. Table 3 shows the current internal organization of the Lombardy Region; it is divided in 16 General Directorates (GDs), 72 Organizational Units and 97 Structures, other than one Area of Specialistic Function and two Central Directions in some cases [24].

Table 3.

Internal structure of the Lombardy Region 1.

2.2.2. The Sub-Regional Level: The Metropolitan City of Milan

Metropolitan Cities are territorial authorities of wide areas established by the Law n.56/2014, whose institutional purposes concern: the strategic development of the metropolitan area; promotion and management of services, infrastructures and communication networks; and management of institutional affairs, including those with European cities and metropolitan areas (article 1, paragraph 2, Law n.56/2014).

Metropolitan Cities replaced the homonymous Provinces, so that they exercise their functions, as well as the additional ones, that the State and Regions can assign to them (article 1, paragraph 44 and 46, Law n.56/2014). In Italy, there are 14 Metropolitan Cities. The fundamental functions concern:

- adoption and annual update of a three-year metropolitan strategic plan;

- general territorial planning (communication structures, networks and infrastructures);

- public services management;

- mobility management and urban planning compatibility;

- promotion and coordination of economic and social development;

- promotion and coordination of digitization systems in metropolitan areas.

Milan is the only metropolitan City within the Lombardy Region and it assumes additional functions, such as the valorization of the Idroscalo, and protected areas and parks at the metropolitan scale (article 33, paragraph 1, paragraph e and paragraph 7, Statute of the Metropolitan City of Milan).

The internal structure of the Metropolitan City of Milan is organized into a macro-structure (divided into different Directorates) and a microstructure composed of services and offices, which vary with the evolution of needs and available resources (articles 9 and 10, Regulation on the organization of offices and services).

Currently, there is one General Directorate and four Areas, both organized in different Sectors, 22 in total [25] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Internal structure of the Metropolitan City of Milan 1.

2.2.3. The Sub-Regional Level: The 11 Provinces of Lombardy

The administrative functions of Provinces are conferred by the State or by regional laws (article 118, second sentence, Constitution of the Italian Republic). Since the Law n.56/2014 (the so-called “Legge Delrio”) has established the Metropolitan Cities, the role of Provinces has been modified in the secondary governmental authority of the vast area (i.e., of second degree). Their fundamental functions concern (article 1, paragraph 85, Law n.56/2014):

- provincial spatial planning of coordination;

- provincial planning of transport services;

- provincial planning of the school network;

- data collecting and processing, and technical-administrative assistance to local authorities;

- management of school buildings;

- control of employment discriminatory phenomena and promotion of equal opportunities within the province.

In addition, Provinces whose territory is entirely mountainous and bordering with foreign countries are assigned further fundamental functions (article 1, paragraph 86, Law n.56/2014) related to the strategic development of the territory, service management and institutional affairs. Furthermore, many regional laws followed the Law “Delrio” to reorganize the functions, such as the Regional Law of Lombardy n.19/2015. Among functions transferred to Regions, we can mention those related to the environment and energy (limited to water concessions, dams, trans-frontier waste disposal and geothermal resources), agriculture, forestry, hunting and fishing (articles 1 and 2, Regional Law n.19/2015); however, the local police functions, including those in agriculture, forestry, hunting and fishing, were preserved to the Provinces. In the Lombardy Region, the Province of Sondrio represents the exception of the “entirely mountain territory, bordering with foreign countries”, so that it conserves those functions transferred to the Regions.

By comparing different organizational structures of Provinces, analyses show a strong element of heterogeneity: each institution is organized in hierarchical levels with variable denomination (i.e., areas, sectors, operational units, services, etc.) to which different offices and competences belong. The outcome of this analysis is presented in the following section.

3. Results

3.1. Local Authorities’ Internal Organization through the IFMA Reading Grid (Research Step 1)

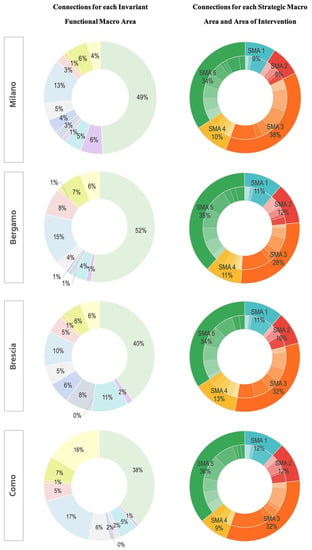

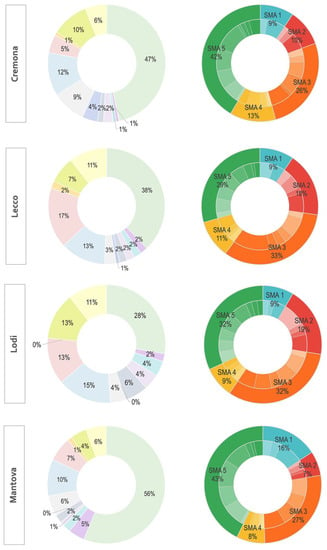

The results of the IFMA reading grid application to the Provinces and to the Metropolitan City of Milan are shown in the following graphs (Figure 3); for each authority, it has been quantified how many offices (i.e., the minimum level of the organizational structure) belong to a single IFMA.

Figure 3.

Invariant Functional Macro Areas (IFMA) classification for Provinces and Metropolitan City of Milan (Milano). (Refer to Table 5 for the color legend).

Table 5 shows the quantity (i.e., total number and percentage) of provincial offices assigned to each IFMA; this synthesis enables the highlighting of the main results. Offices with institutional, administrative and economic functions, assigned to the IFMA “Management Services”, constitute the major component in most Provinces; an average of 26% of all provincial offices belongs to this category, the maximum value being 42% in the Province of Lodi. Even the IFMA “Environment” consists of numerous offices, representing on average 21% of all provincial offices; Cremona reaches a peak of 30%, while Varese ranks last with only 9%. By contrast, very few offices are concerned with European projects, strategic agendas and statistics issues, making the IFMA “Europe” the least represented functional area (reaching only 1% on average); in 50% of cases, there are no offices, while in the remaining 50%, there are only one or two offices.

Table 5.

Synthesis of results: number and percentage of provincial offices per Invariant Functional Macro Areas (IFMA).

Overall, a total amount of 508 provincial offices have been analyzed, considering the 12 Provinces (including the Metropolitan City of Milan). The maximum number of offices per Province was 81 (in the case of Brescia) and the minimum was 22 (in the case of Sondrio), while the Metropolitan City if Milan is comprised of 27 offices (called Sectors).

Section 4 of “Discussion” provides a detailed description and interpretation of these results.

3.2. Areas of Competence among Different Levels of Government (Research Step 2)

After having applied the IFMA classification to different Provinces and to the Metropolitan City of Milan, the second type of analysis concerned the comparison between competences of different levels of government (i.e., the Lombardy Region, the Provinces and the Metropolitan City of Milan). By doing so, the IFMA reading grid has also been applied to the regional internal structure.

The flowchart in Figure 4 shows the complex relations that have been identified between the competences of the Region and those of the Provinces; the latter are represented through the synthetic IFMA scheme, which allows comparison one (the Lombardy Region) to many (the Provinces, including the Metropolitan City of Milan).

Figure 4.

Comparison between regional and local authorities’ structures using Invariant Functional Macro Areas (IFMA). (Refer to Table 5 for the color legend).

At the Regional level, the flowchart shows that lots of IFMA are fragmented in different General Directorates and, simultaneously, single GDs group together many IFMA: eight out of 16 GDs are multifunctional (the 50% of cases), two of which include up to five different IFMA (i.e., the GDs of Presidency and of Agriculture, food and green systems). The IFMA “Education, professional training, labour and social policies” is the more fragmented functional macro area with seven different GDs involved.

A broader interpretation of these results is provided in Section 4 of “Discussion”.

3.3. Coherence of Territorial and Local Authorities’ Competences with the SRSvS Targets (Research Step 3)

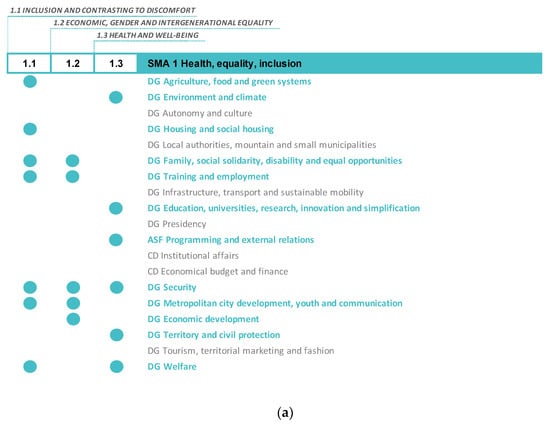

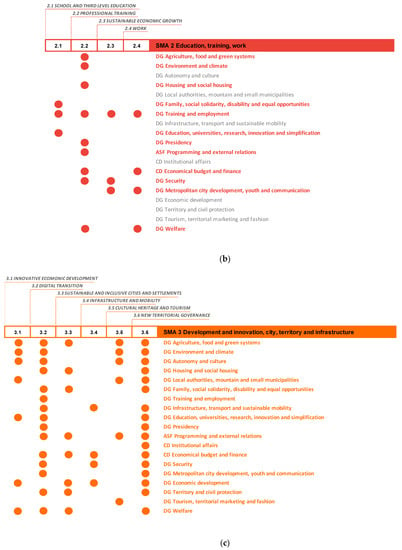

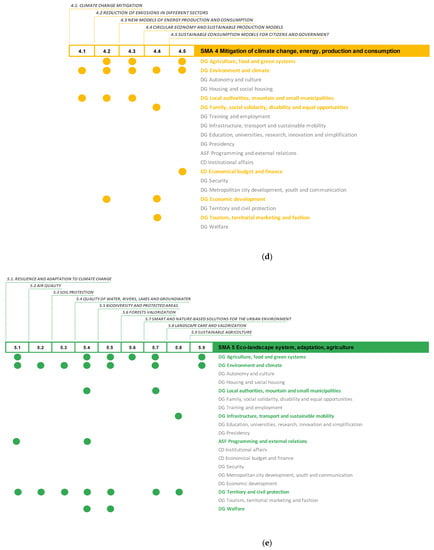

The coherence analysis between the authorities’ competences and their Strategic targets included in the SRSvS has been conducted by deepening how the single Strategic Macro Areas (SMA) of the Regional Strategy are addressed at the regional and local levels.

Firstly, the study examined and identified the existing relations between the SMA of the Strategy and the regional offices (i.e., the General Directorates and their Structures), according to their competences and functions. The results have been organized in two pie charts (Figure 5) that show (as a percentage):

- the number of connections for each General Directorate;

- the number of connections for each SMA and each Area of Intervention (inner and outer crowns respectively).

The results highlight the extent to which regional GDs are currently structured on the basis of the SMA challenges; on the other hand, they highlight which SMA are sufficiently faced by the regional authority and which SMA need better implementation.

Figure 5.

Connection between regional competences and the Strategic Macro Areas (SMA): percentage of connections for each General Directorates (a); percentage of connection for each SMA and Area of Intervention (AI) (inner and outer crowns respectively) (b). (Refer to Table 6 for the color legend of Figure 5a).

The first pie chart (Figure 5a) shows that 32% of all connections concern the GDs “Agriculture, food and green systems” and “Environment and climate”; these are the Directorates that primarily address the SRSvS targets and, in particular, those related to the environmental dimension of sustainability. Accordingly, their total Structures amount to 18% of all regional offices. Secondly, the GD “Welfare” shows a good number of Structures (14% of all offices) as well as connections with SMA (12%). However, problems of inclusion and social equality (within SMA 1) are not sufficiently tackled by the Region; the GD “Welfare” is responsible for the health system, with regard to prevention and health care (AI 1.3), yet it does not deal with social inclusion and contrast to discomfort (AI 1.1), nor with economic, gender and intergenerational equality (AI 1.2). Finally, although many Structures are part of the GD “Presidency” (23% of all offices), the number of connections with the SMA appears insignificant (only 12%). Table 6 synthetizes these results.

The second pie chart (Figure 5b) focuses the attention on the SMA and their AI.

SMA 1 “Health, equality, inclusion” and SMA 2 “Education, training, work” (both regarding the social dimension of sustainability), together with SMA 4 “Mitigation of climate change, energy, production and consumption”, are the areas least addressed by regional GDs; they reach 14%, 10% and 8% of connections, respectively. Instead, SMA 3 “Development and innovation, city, territory and infrastructure” reaches 43% of all connections, while SMA 5 “Eco-landscape system, adaptation, agriculture” reaches 25%. A large part of SMA 3 connections is linked to participative governance (AI 3.6).

Similar to the analysis conducted for the Region, the existing relations between the SMA of the Strategy and the provincial or metropolitan offices have been identified. The comparison, in this case, was conducted through the IFMA reading grid; for each Province and for the Metropolitan City of Milan, the quantity of identifiable connections for each IFMA (pie charts on the left) and for each SMA and AI (pie charts on the right—inner and outer crowns respectively) were examined (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Connections between Provincial and Metropolitan competences and the Strategic Macro Areas (SMA): percentage of connections for each Invariant Functional Macro Area (IFMA) (a); percentage of connections for each SMA and Area of Intervention (inner and outer crowns respectively) (b). (Refer to Table 5 for the color legend of Figure 6a).

Table 6.

Synthesis of results: percentage of connections with Strategic Macro Areas (SMA) (left column) and percentage of regional offices (i.e., Structures) for each General Directorates (right column).

Table 6.

Synthesis of results: percentage of connections with Strategic Macro Areas (SMA) (left column) and percentage of regional offices (i.e., Structures) for each General Directorates (right column).

| Regional GDs | Percentage of Connections with SMA | Percentage of Regional Offices |

|---|---|---|

| GD Agriculture, food and green systems | 22% | 11% |

| GD Environment and climate | 10% | 7% |

| GD Autonomy and culture | 2% | 3% |

| GD Housing and social housing | 3% | 2% |

| GD Local authorities, mountain and small municipalities | 3% | 3% |

| GD Family, social solidarity, disability and equal opportunities | 3% | 4% |

| GD Training and employment | 5% | 5% |

| GD Infrastructure, transport and sustainable mobility | 3% | 5% |

| GD Education, universities, research, innovation and simplification | 5% | 5% |

| GD Presidency | 12% | 23% |

| GD Security | 2% | 1% |

| GD Metropolitan city development, youth and communication | 3% | 3% |

| GD Economic development | 4% | 4% |

| GD Territory and civil protection | 9% | 7% |

| GD Tourism, territorial marketing and fashion | 1% | 2% |

| GD Welfare | 12% | 14% |

| TOTAL | 100% | 100% |

The main outcome of the first pie charts (Figure 6a) is that, in all administrations, sustainability issues are generally addressed by the provincial and metropolitan offices belonging to the IFMA “Environment”. The maximum number of connections in this IFMA is reached by the Province of Mantova (56% of all connections), while the minimum is reached by Varese (22%).

From the second pie charts (Figure 6b), it clearly appears that, in all Provinces as well as in the Metropolitan City of Milan, SMA 3 “Development and innovation, city, territory and infrastructure” and SMA 5 “Eco-landscape system, adaptation, agriculture” reach the greatest percentages of connections (an average of around 32% and 34%, respectively). On the other hand, the SMA 1 “Health, equality, inclusion” and SMA 2 “Education, training, work”, both concerning the social dimension of sustainability, as well as the SMA 4 “Mitigation of climate change, energy, production and consumption”, reach very low percentages.

4. Discussion

The main findings of the research are discussed below, in accordance with the three phases of the research:

- the local authorities’ internal organization, through the IFMA reading grid (Section 3.1);

- the areas of competence between different levels of government (Section 3.2);

- the coherence of territorial and local authorities’ competences with the SRSvS targets (Section 3.3).

The main outcomes of the first two analyses on the organizational structures of territorial and local authorities (Section 3.1 and Section 3.2) show significant heterogeneity and fragmentation of functions, as a result of institutions’ managerial autonomy and of the sectoral approach. Planning for sustainability requires good levels of coordination that overcome “in silos” organization within each institution, as well as the administrative man-made boundaries in which our territories are organized. However, despite the holistic character of sustainability goals, the sustainability functions too often reside within a single department, usually the environmental one [2,4].

In the case of the Lombardy Region, as a result of the internal structure analysis, there is no explicit and dedicated GD for sustainable development. Although there is the importance of prioritizing and considering the theme of sustainable development as a pervasive and transversal target, i.e., a core value [4], the lack of a dedicated GD emphasizes the need of improving the governance framework within the regional administration, putting the SRSvS construction and implementation at the center of all other regional policies and actions in the hands of different GDs. This means that RSDS goals should become the basis of planning choices for the definition of plans and programs [26]. The flexibility required for reaching this goal may collide with the limited feasibility of adaptation of existing plans and programs to the RSDS vision, as well as with the complex interaction between different GDs. It follows that territorial systems, such as that of the Lombardy Region, need to increment innovation with regard to their organizational structures; for instance, by setting up transversal working groups for sustainability or sustainability-dedicated staff [6].

Even on the scale of the Provinces, there are no dedicated offices for sustainable development and very few provincial offices are dedicated to European projects, strategic agendas and statistics. These results clearly highlight the structural weakness of addressing EU policies and strategic agendas, as it is with the UN 2030 Agenda on climate change and sustainable development, in a proactive way. As a consequence, Provinces have a poor ability to become a strong reference for Municipalities to address sustainability challenges. This situation is compounded by the fact that the Province has become a secondary governmental authority.

The lack of coordination between departments, both internally and externally, to the authorities, is also highlighted by the application of the IFMA classification to different levels of government (Section 3.2). The IFMA classification allows identification in a schematic and simple way which are the main areas of competence of authorities, in respect to their internal sectors or departments; this can help to improve coordination mechanisms between levels of government and to strengthen their institutional relations (the so-called “vertical” or “multi-level” governance). The results show how complex it can be to overcome the current “in silos” functional organization; identifying which are the departments or the technical offices, within different authorities, that are responsible for a particular subject may not be easy, because of the extreme fragmentation of sectoral competences. The current organization responds to sectoral operational needs, while the implementation and territorialization of sustainability strategies requires a transversal and interdisciplinary approach that involves all sectors. In this regard, territorial and local authorities need to improve their ability to move from the aspect of “ordinary management” to the “strategic vision” of sustainable development programs. A solution may arise from the revision of the institutions’ organization as well as from the empowerment of well-structured multi-level governance. Similarly, other researchers have observed this problem at the national level; Soberón M. et Al. (2020) show that coordination approaches should be introduced to promote internal collaboration and to overcome the “silo” logic [11].

The third part of the analyses concerns the integration between institutional functions and the SRSvS targets, that are made explicit through the SMA (Section 3.3). The results highlight: (i) the extent to which offices (i.e., regional GDs and provincial and metropolitan offices) are currently structured on the basis of the SMA challenges; and (ii) which SMA are sufficiently faced by the authorities or, on the contrary, which SMA need to be better implemented.

In the case of the Region, the SMAs that require to be strengthened are SMA 1, 2 and 4; neither social issues nor the urgent challenges of energy transition, greenhouse gas emissions and circular economy are adequately addressed by the regional administration in relation to the priorities expressed in its strategy. The regional result is critically confirmed within the Provinces and the Metropolitan City as well.

More efforts need to be made in this direction, because setting a strong coherence among sectors and sustainability goals (i.e., SMA of SRSvS for this case study) could facilitate the success of sustainability strategies, as well as simplify the work of different authorities.

The Region could re-structure its internal sectors in accordance with the sustainability strategy; a reinterpretation of regional offices could implement the SRSvS, strengthen the internal governance and increase new collaborative attitudes, both internally and externally. The connections established between regional functions and the SRSvS targets were used to propose a compromise solution: to identify potential working tables for strategic actions on the individual SMA. More specifically, for each SMA and AI, GDs who may be interested in collaborating on strategic topics were identified (Figure 7). This could be an example of a solution to assist decision-making on such cross-cutting challenges and targets.

Figure 7.

General Directorates (GDs) potentially involved in regional working tables on each Strategic Macro Area (SMA) and Area of Intervention (AI): SMA 1 Health, equality, inclusion (a); SMA 2 Education, training, work (b); SMA 3 Development and innovation, city, territory and infrastructure (c); SMA 4 Mitigation of climate change, energy, production and consumption (d); SMA 5 Eco-landscape system, adaptation, agriculture (e).

The working tables show the high interdisciplinarity of sustainability targets, so that many GDs are called to collaborate. In particular, the working table for the SMA 3 “Development and innovation, city, territory and infra-structures” potentially requires the participation of almost all the GDs and, thus, numerous offices. In this case, the identification of delegated offices could be necessary to manage systemic issues, such as the AI 3.2 on “digital transition” and the AI 3.6 on “new territorial governance”.

The approach presented in the research could be applied to and between local authorities as well (i.e., the Provinces and the Metropolitan City of Milan), in order to create multi-level well-structured governance for sustainability and climate actions. Moreover, this method could be exported and applied to different contexts, such as the other Italian Regions, because of the high level of heterogeneity that characterizes the management of territories between several levels of government.

Regarding the possible solutions, there could be multiples barriers during the establishment of cross-sectional working tables, such as the instability and overlapping of government mandates that could increase the complexity of the process. Transversal aggregations within one public administration should be monitored over time and become flexible, according to the evolution of both its internal organization and its strategic objectives. This flexibility and dynamism should be increased both in the territorial climate governance and in sectoral plans and programs (i.e., in urban planning), in order to better integrate sustainability targets throughout the planning and action process [26].

To conclude, some research limits could be overcome by future developments. First of all, some outcomes are impacted by lack of data, their level of update and detail; the database, that constitutes the cognitive basis for the analyses conducted in this research, was developed through the consultation of official documents (i.e., official Statutes and Regulations) and institutional portals that not always are available, accessible, complete (i.e., of high quality) and interoperable [27]. For this reason, the higher the degree of detailed information on the authorities’ functions and competences, the more possible connections with SMAs.

Furthermore, the IFMA reading grid was arbitrarily developed by the authors of this contribution, in accordance with the official available information and with the purpose of the research. Future research could directly involve the territorial and local administrations; a direct dialogue and comparison with the authorities would lead to a validation of the IFMA reading grid and would strengthen the research findings.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the extent to which authorities’ competences are aligned to the RSDS targets, by looking at the main functional areas of competence of local authorities and at the level of coordination among different levels of government (research questions).

The main results highlighted the barriers that challenge the implementation of Sustainable Development Strategies at the regional and local levels, by looking at public authorities’ administrative capacities and resources to deal with complex and cross-sectoral policies. Having deepened the integration between organizational structures of public authorities and the RSDS targets, in the case study of the Lombardy Region, the research has shown how sectoral fragmentation of competence collides with the holistic layout of sustainability. New integrated approaches are needed to strengthen cross-sectoral dialogue and cooperation within and between public institutional bodies, to better link them to sustainability targets and to transform all sustainability dimensions in the core values of plans and programs.

The experience of the Lombardy Region, and its Provinces and the Metropolitan City, could inspire other municipalities and territories to improve themselves; from a general point of view, to implement their sustainability strategies, and in specific, to enhance their internal organizational capacity of effecting sustainability policies. This approach allows territorial and local authorities to review their organizations based on the main targets of NSDS or RSDS. Strengthening this integrated approach to the UN 2030 Agenda, localization can enhance organizational coherence and coordination between different levels of government. For achieving these aims, the following are required: (i) strong coordination of existing processes and levels of government [5] that should be better implemented; (ii) large flexibility between sectoral plans and programs; and (iii) good timing in adaptation to numerous changes (i.e., organizational changes) [4]. These kinds of challenges are faced not only by Italian territories and Regions, such as the present case study, but also by those countries whose territorial administration is organized in such a federal way. In fact, the simultaneous presence of multiple and autonomous institutions that concur to common sustainability targets requires a well-organized, coherent and collaborative multi-level governance, in order to spread and realize the holistic vision supported by the UN 2030 Agenda itself.

Finally, the research identifies what the Italian VNR calls “enabling factors” and identifies them as specific implementation tools of the NSDS (and RSDS), as well as fundamental levers to support the transformative process triggered by the UN 2030 Agenda, also at the international level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and A.R.; methodology, S.B. and A.R.; investigation, S.B.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, A.R.; visualization, S.B.; supervision, A.R.; project administration, A.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project INTEGRA—Integrazione modellistica a supporto della governance e della strategia regionale di sviluppo sostenibile (Modeling integration to support governance and regional sustainable development strategy) (funded by the Italian Ministry of Ecological Transition), grant number (CUP) D79C20000200001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The list of data consulted is detailed in Appendix A.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been conducted in collaboration with the Italian inter-university PhD course on sustainable development and climate change (link: www.phd-sdc.it, accessed on 28 January 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

List of consulted sources for the analysis of public authorities’ internal organization and competences. The research was conducted between April and July 2022.

- Lombardy Region:

- Regional Statutory Law n.1 of 30 August 2008 “Statuto d’autonomia della Lombardia” (Statute of autonomy of Lombardy); BURL n.35, 1st Suppl. ord. of 31/08/2008

- Decree n.677 of 08 January 2021 “Determinazioni in ordine alla composizione della giunta regionale” (Determinations regarding the composition of the regional government)

- Regional organizational chart, available at the website: https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/portal/istituzionale/HP/DettaglioAT/Istituzione/Amministrazione-Trasparente/organizzazione/articolazione-degli-uffici/organigramma-della-giunta-regionale/organigramma-della-giunta-regionale (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Regional General Directorates, available at the website: https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/portal/istituzionale/HP/istituzione/direzioni-generali (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Metropolitan City of Milan:

- Statute of the Province of Milan, approved by the resolution of the Metropolitan Conference of Mayors n.2 of 22 December 2014 and modified by the resolution n.6 of 25 September 2018, available at the website: https://www.cittametropolitana.mi.it/portale/conosci_la_citta_metropolitana/Statuto_regolamenti/statuto_citta_metropolitana_milano.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://www.cittametropolitana.mi.it/portale/amministrazione-trasparente/organizzazione/articolazione_uffici.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- “Regolamento dell’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi” (Regulation on the organization of offices and services), approved by the resolution of the Provincial Council n.302512/2.3/2010/1 of 20 December 2013 and modified by the Decree of the Metropolitan Mayor n.252/2021 of 24 November 2021, available at the website: https://www.cittametropolitana.mi.it/portale/conosci_la_citta_metropolitana/Statuto_regolamenti/regolamenti.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Province of Bergamo:

- Statute of the Province of Bergamo, approved on 05 March 2015 and modified on 31 October 2019, available at the website: https://www.provincia.bergamo.it/cnvpbgrm/zf/index.php/atti-generali/index/dettaglio-atto/atto/2 (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts of the Province of Bergamo, available at the website: https://www.provincia.bergamo.it/cnvpbgrm/zf/index.php/servizi-aggiuntivi/index/index/idtesto/1883 (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Province of Brescia:

- Statute of the Province of Brescia, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.3/2015 and modified by the resolution n.3/2022, available at the website: https://www.provincia.brescia.it/istituzionale/documenti/statuto-della-provincia-di-brescia-approvato-con-deliberazione-dellassemblea (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://www.provincia.brescia.it/istituzionale/organigramme (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Decree n.250 of 06 June 2000 “Regolamento dell’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi” (Regulation on the organization of offices and services), last modified by Decree n.167 of 21 May 2021, available at the website: https://www.provincia.brescia.it/istituzionale/documenti/regolamento-dellordinamento-degli-uffici-e-dei-servizi-0 (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Province of Como:

- Statute of the Province of Como, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.1 of 22 June 2015, available at the website: https://www.provincia.como.it/documents/118973/400427/Reg001_Statuto_Provincia_Como.pdf/29edb391-1903-feae-5793-2a26645f2a48?t=1582213166538 (accessed on 02 May 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://www.provincia.como.it/it/web/provincia-di-como/settori-e-uffici (accessed on 02 May 2022).

- Province of Cremona:

- Statute of the Province of Cremona, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly of 23 December 2014, available at the website: https://www.provincia.cremona.it/gov/?view=Pagina&id=3885 (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://www.provincia.cremona.it/risorseumane/?view=Pagina&id=3071 (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Province of Lecco:

- Statute of the Province of Lecco, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.1 of 04 March 2015 and last modified with resolution n.5 of 25 June 2019, available at the website: https://www.provincia.lecco.it/pr-lecco-media/2020/06/SITO-Statuto-modificato-giu-2019.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Organizational chart, available at the website: https://www.provincia.lecco.it/documento/organigramma-della-struttura-organizzativa/ (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Functions of Administrative Areas, available at the website: https://www.provincia.lecco.it/amministrazione/aree-amministrative/ (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Province of Lodi:

- Statute of the Province of Lodi, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.1 of 29 January 2015 and modified by the resolution n.1 of 16 April 2019, available at the website: https://www.provincia.lodi.it/wp-content/uploads/Statuto-della-Provincia-di-Lodi.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://www.provincia.lodi.it/gli-uffici/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- “Regolamento dell’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi” (Regulation on the organization of offices and services), approved by the resolution of the Provincial Council n.267 of 15 December 2010 and last modified by the Council deliberation n.26 of 22 December 2016, available at the website: https://www.provincia.lodi.it/amministrazione/statuto-e-regolamenti/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Province of Mantova:

- Statute of the Province of Mantova, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.1 of 04 April 2017 and modified by the resolution of the Provincial Council n.41 of 30 September 2021, available at the website: https://www.provincia.mantova.it/context_docs.jsp?ID_LINK=78&area=5 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://www.provincia.mantova.it/context_sublink.jsp?ID_LINK=76&area=5 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- “Regolamento dell’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi” (Regulation on the organization of offices and services), approved by the resolution of the Provincial Council n.1 of 19 January 2006 and last modified by the resolution n.104 of 16/09/2021, available at the website: https://www.provincia.mantova.it/context_docs.jsp?ID_LINK=78&area=5 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Province of Monza-Brianza:

- Statute of the Province of Monza-Brianza, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.1 of 30 December 2014, available at the website: https://www.provincia.mb.it/conosci_provincia/statuto-e-regolamenti/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://www.provincia.mb.it/conosci_provincia/struttura-organizzativa/ “Regolamento dell’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi” (Regulation on the organization of offices and services), approved by the resolution of the Provincial Council n.78 of 23 July 2014 and last modified by the resolution n.56 of 20 May 2021, available at the website: https://www.provincia.mb.it/export/sites/monza-brianza/doc/regolamenti_decreti/uffici_servizi/ROUS-aggiornato-2021.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Province of Pavia:

- Statute of the Province of Pavia, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.1 of 24 October 2016, available at the website: https://dait.interno.gov.it/documenti/statuti/statuto-provincia-pv-pavia.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://provinciapv.trasparenza-valutazione-merito.it/web/trasparenza/dettaglio-trasparenza?p_p_id=jcitygovmenutrasversaleleftcolumn_WAR_jcitygovalbiportlet&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-2&p_p_col_count=1&_jcitygovmenutrasversaleleftcolumn_WAR_jcitygovalbiportlet_current-page-parent=11705&_jcitygovmenutrasversaleleftcolumn_WAR_jcitygovalbiportlet_current-page=11709 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- “Regolamento dell’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi” (Regulation on the organization of offices and services), approved by the resolution of the Provincial Council n.541/38149 of 27 October 2004 and last modified by the resolution n.214 of 12 October 2021

- Province of Sondrio:

- Statute of the Province of Sondrio, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.1 of 22 December 2014, available at the website: https://www.provinciasondrio.it/pagine/statuto-della-provincia-di-sondrio (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://www.provinciasondrio.it/amministrazione-trasparente/organizzazione/articolazione-uffici (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- “Regolamento dell’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi” (Regulation on the organization of offices and services), approved by the Presidential Resolution n.82 of 28 August 2019, available at the website: https://www.provinciasondrio.it/regolamenti (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Province of Varese:

- Statute of the Province of Varese, approved by the resolution of the Mayors’ Assembly n.6 of 31 July 2019, available at the website: http://www.provincia.va.it/code/11985/Statuto (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Organizational and functional charts, available at the website: https://servizi-provincia-varese.e-pal.it/L190/atto/show/74993?search=&idSezione=1621&activePage=&sort= (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- “Regolamento dell’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi” (Regulation on the organization of offices and services), approved by the Presidential Resolution n.170 of 10 December 2020, available at the website: http://www.provincia.va.it/code/83051/Regolamenti-Delibere-Presidenziali (accessed on 14 July 2022).

References

- Fenton, P.; Gustafsson, S. Moving from high-level words to local action—governance for urban sustainability in municipalities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.; Diprose, K.; Taylor Buck, N.; Simon, D. Localizing the SDGs in England: Challenges and Value Propositions for Local Government. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, A.; Leininger, J.; Tosun, J. Integrated Policymaking: Choosing an Institutional Design for Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS): Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Krantz, V.; Gustafsson, S. Localizing the sustainable development goals through an integrated approach in municipalities: Early experiences from a Swedish forerunner. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 2641–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardal, K.G.; Reinar, M.B.; Lundberg, A.K.; Bjørkan, M. Factors facilitating the implementation of the sustainable development goals in regional and local planning-experiences from Norway. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarini, E.; Mori, E.; Zuffada, E. Localizing the Sustainable Development Goals: A managerial perspective. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2022, 34, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Stokan, E. Sustainability Synergies or Silos? The Opportunity Costs of Local Government Organizational Capabilities. Public Adm Rev. 2020, 80, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MASE. La Strategia Nazionale per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile. Available online: https://www.mite.gov.it/pagina/la-strategia-nazionale-lo-sviluppo-sostenibile (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- MiTE; MAECI. Voluntary National Review. Italy 2022. Available online: https://hlpf.un.org/countries/italy/voluntary-national-review-2022. (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- OECD. Italy Governance Scan for Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Soberón, M.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T.; Urquijo, J.; Pereira, D. Introducing an organizational perspective in sdg implementation in the public sector in Spain: The case of the former ministry of agriculture, fisheries, food and environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PON Governance e Capacità Istituzionale 2014–2020. CReIAMO PA—Competenze e reti per L’integrazione Ambientale e per il Miglioramento delle Organizzazioni della PA. Available online: http://www.pongovernance1420.gov.it/it/progetto/creiamo-pa-competenze-e-reti-per-lintegrazione-ambientale-e-per-il-miglioramento-delle-organizzazioni-della-pa/ (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Meuleman, L. Metagovernance for Sustainability. In A Framework for Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. Codici Statistici delle Unità Amministrative Territoriali: Comuni, Città Metropolitane, Province e Regioni. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/6789 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Regione Lombardia. Economia. Available online: https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/portal/istituzionale/HP/DettaglioRedazionale/scopri-lalombardia/economia/economia-lombarda/red-economia (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Eurostat. Population on 1 January by Age, Sex and Region. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_r_d2jan/default/map?lang=en (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Eurostat. Area by Region. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/reg_area3/default/map?lang=en (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Eurostat. Population Density. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00003/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Eurostat. Population Density by Region. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_r_d3dens/default/map?lang=en (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- SNPA. DICSIT—Database Indicatori Consumo di Suolo in Italia. Available online: https://webgis.arpa.piemonte.it/secure_apps/consumo_suolo_agportal/?entry=5 (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- United Nations. Voluntary Local Reviews. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/topics/voluntary-local-reviews (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Medeiros, E.; van der Zwet, A. Sustainable and integrated urban planning and governance in metropolitan and medium-sized cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhao, Z. The Research on the Spatial Governance Tools and Mechanism of Megacity Suburbs Based on Spatial Evolution: A Case of Beijing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Lombardia. Direzioni Generali. Available online: https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/portal/istituzionale/HP/istituzione/direzioni-generali (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Città metropolitana di Milano. Articolazione degli uffici. Available online: https://www.cittametropolitana.mi.it/portale/amministrazione-trasparente/organizzazione/articolazione_uffici.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Frigione, B.M.; Pezzagno, M. The Strategic Environmental Assessment as a “Front-Line” Tool to Mediate Regional Sustainable Development Strategies into Spatial Planning: A Practice-Based Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.; Frigione, B.M.; Pezzagno, M.; Richiedei, A. L’utilizzo e la condivisione dei dati per la pianificazione sostenibile del territorio, tra interesse collettivo e governance multiattoriale. In Proceedings of the XXIV SIU National Conference, Worthing Values for Urban Planning, Brescia, Italy, 23–24 June 2022; Planum Publisher: Roma, Italy; Milano, Italy, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).