1. Introduction

The rural dwelling is not only an important element of a locale’s daily landscape, but also an important focus of vernacular architectural research. Since the 1960s, Western architectural historians developed standards for research in vernacular architecture, often placing rural dwellings at the core of their studies.

The earliest research on vernacular architecture in the United States began with the survey and recording of colonial buildings in the late 19th century. Professors Norman Isham, J. Frederick Kelly and other architectural historians conducted extensive mapping and investigations of New England’s vernacular architecture of the 17th and 18th centuries. (New England is located in the northeastern corner of the continental United States, bordering the Atlantic Ocean and Canada. New England, a former British colony, was established in the 17th century. It is currently the collective name of six states in the United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.) They found that through analysis of the facades, structures, planes, and aesthetics of these buildings, a more in-depth understanding of their history and significance unfolds [

1]. These buildings hold more than aesthetic significance, becoming a portal into the culture at that time [

1,

2].

After the reform and opening up, great changes have taken place in China’s urban and rural landscape, especially in the rural areas in the suburbs. This originated from the late 1950s, when modernist architecture gradually became the mainstream. The scientific design method of western modern architectural design theory was introduced until it became the standard operation method. Contemporary traditional Chinese villages have almost completed a spontaneous modernization transformation. The local self-construction activities in the vast suburban and rural areas have gradually abandoned the skills of the classical era, and combined with the logical thinking and spatial organization of the western modern architectural trend. This constitutes the theoretical basis for the innovation of contemporary rural vernacular architecture.

At the same time, the rich and diverse samples of China’s vernacular architecture have also long intrigued Western scholars. Rudolfsky’s exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1964–1965, “Architecture Without Architects”, displayed Chinese vernacular architecture from all over the country. (Bernard Rudolfsky organized an exhibition entitled “Architecture without Architects” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1964, and subsequently published a book of the same name. The book redefines the history of architecture and focuses on the construction of vernacular architecture around the world. Vernacular architecture is usually irrelevant to fashion. It is almost eternal and cannot be improved, because the goal achieved is perfect. However, the origin and construction methods of vernacular architecture have been forgotten.) His concern for rural and traditional houses posited a new attitude for domestic and foreign architectural theory circles, finding significance and creative design ideas of architecture inspired by daily residences and local construction techniques.

Chinese architecture professionals have also been interested in the implications of vernacular architecture. Mr. Wu Liangyong put forward the subject of “Regionalization of Modern Architecture” and “Modernization of Local Architecture” very early in the 1980s [

3]. Vernacular architecture is an important part of regional architecture, which is called “Architecture Without Architects” in the West. This title emphasizes the spontaneity, creativity, and sustainability of vernacular architecture. Contemporary vernacular architecture develops dynamically, as does the local culture it reflects [

4]. By studying the material forms of local architecture and evaluating the historical, geographical, cultural customs, and technical factors influencing and restricting its development, we can fully understand the experiences of contemporary Chinese rural citizens.

In addition to paying attention to the vernacular architecture itself, the study of Chinese vernacular architecture necessitates an analysis of the spirit and beliefs of the Chinese farmers behind it. Diane Shaw mentioned that “the researcher’s challenge is to devise a strategy that will enable buildings to reveal their history and meaning” in the preface to the book

Invitation to Vernacular Architecture: A Guide to the Study of Ordinary Buildings and Landscapes by Thomas Carter and Elizabeth Collins Cromley [

5]. The most challenging aspect of studying vernacular architecture is how to attach importance to these rural dwelling houses that have been ignored by the official history of architecture, how to evaluate their significance with a theoretical method, and how to explain the evolution of rural dwellings. This process is difficult, but that is exactly what this article tries to do.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection of Vernacular Architecture

Building from our analysis of the existing body of research in vernacular architecture and established research methodologies, we selected the most representative traditional villages in Henan, China as our research focus. Henan has a long and rich history, preserving many cultural relics of ancient civilizations of China. Xinxiang is a city located in the northern part of Henan Province, bordering Shanxi and Hebei Province. The landform consists of hills and mountains in the north descending to plains in the centre and south [

6]. The beautiful scenery in the southern Taihang area has brought abundant natural landscape resources to Xinxiang. Xinxiang is the birthplace of Yangshao culture, with a history of 6000 years. (Yangshao culture refers to the Neolithic culture in the middle reaches of the Yellow River. It is a culture with agriculture as its main economic source.) People built houses, and built settlements and villages here. With economic development, the local industrial structure has changed. The upsurge of rural tourism has brought more tourists to Xinxiang. The residents of the villages began to transform their original houses into homestays or hotels. Before and after the 20th century, there were many spontaneous buildings in Xinxiang, and great changes have taken place in local houses. Xinxiang is a precious region for studying Chinese vernacular architecture. Our research intent was to explore how traditional dwellings demonstrate local innovation and spontaneously evolve.

Xinxiang’s elevation descends from high in the west to low in the east and high in the north to low in the south. The region’s topography directly impacted local settlement trends. Different relative positions between the mountains and settlements determined the varying positional relationships and the forms of settlements. Roughly four relational layouts can be seen between the traditional settlements in southern Taihang and the mountain terrain. Landscape positioning also led to four types of settlements: basin settlements, valley settlements, mountainside settlements, and plain settlements away from the mountains. Basin settlements and valley settlements are located at the foot of the mountains.

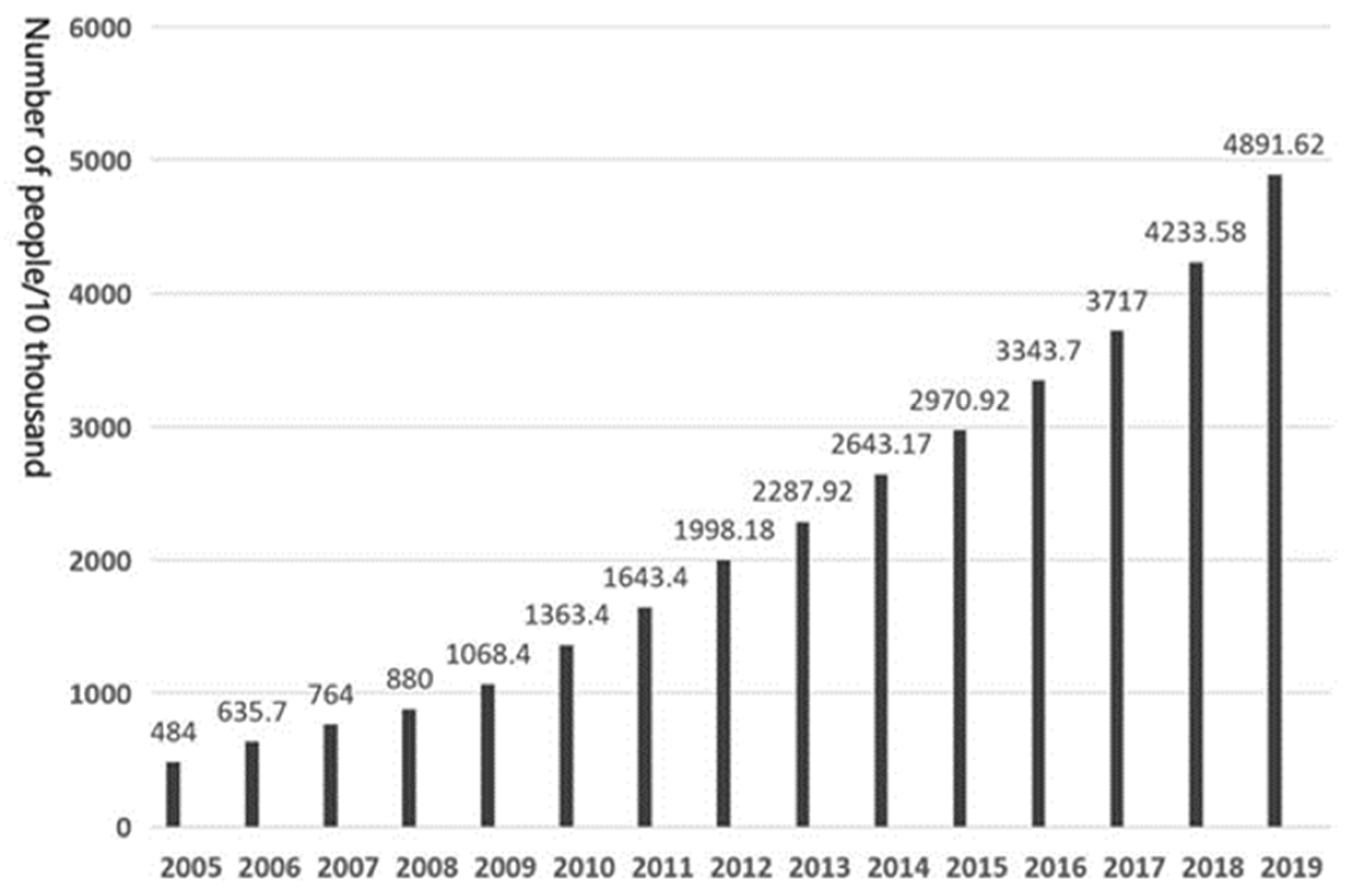

Xinxiang, Henan is rich in opportunities for tourism and tourism development trends have steadily increased in recent years. Xinxiang has 23 A-level tourist attractions, of which 11 are above 4A-level. The combined income of core tourism enterprises reached 410 million yuan at the end of 2019. From the growth seen in the data (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), it is clear that the tourism economy is becoming the main driving force for the improvement of the tertiary service industry and a pillar industry for high-quality economic development.

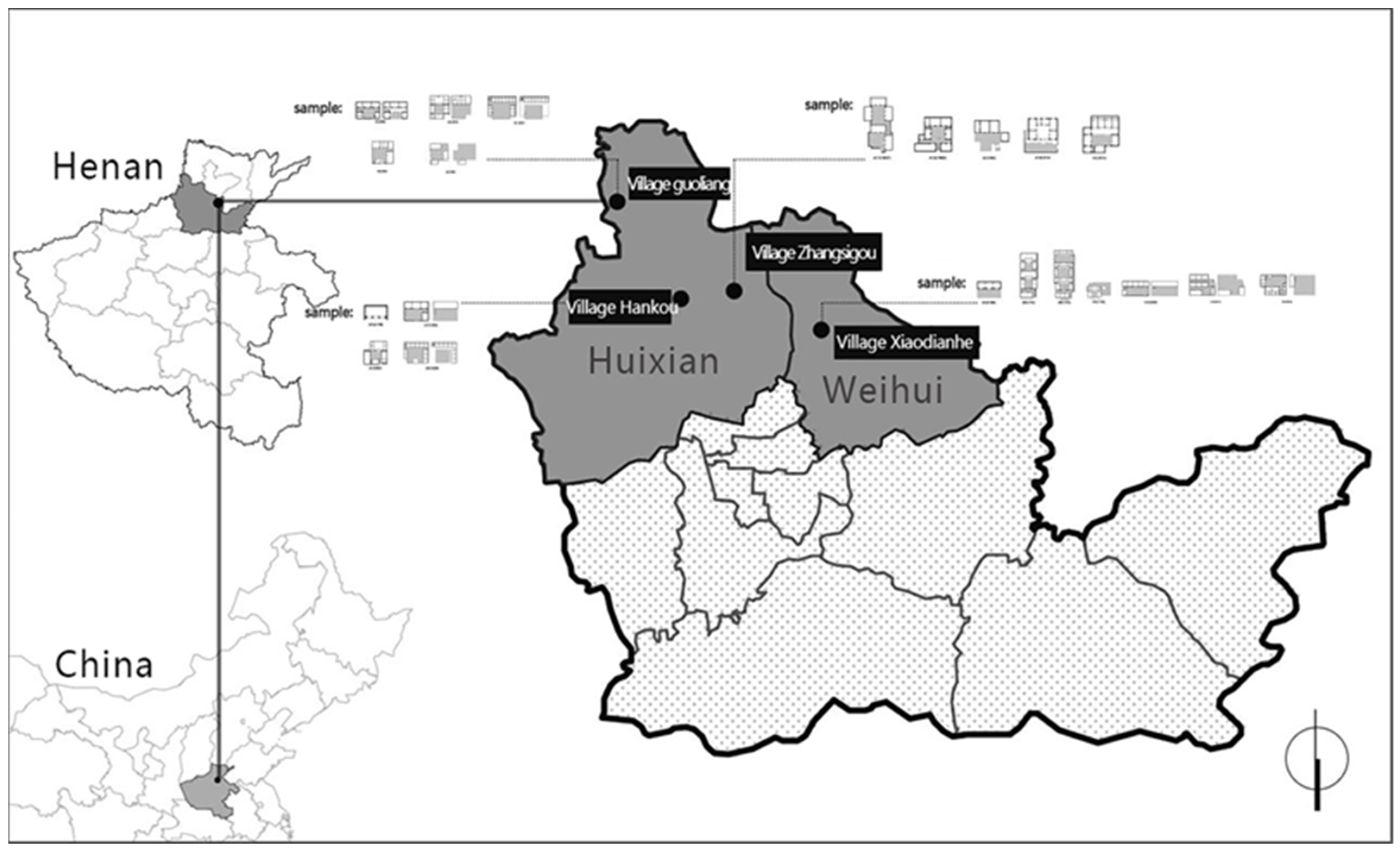

Vigorously developing tourism is both an opportunity and a challenge to the development of South Taihang villages. Not only has it changed the overall style of the villages, but it also has an impact on the spatial structure of vernacular architecture, and the lifestyle of the villagers and the way of making their living. Based on this background, in order to research the spontaneous evolution of vernacular architecture in China, the authors selected the villages Guoliang, Hankou, Zhangsigou, and Xiaodianhe in Huixian City and Weihui City as the research sites. The researchers consider the development scale of tourist villages in the southern Taihang area as the guide and the location characteristics of these villages as the basis (

Table 1). Surveys and mapping of the vernacular architecture in these four villages follow (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

A total of 50 samples were included as part of this study, of which 21 samples were selected for detailed surveying, mapping and interpretation summary (

Table 2). These samples were based on a “three-bay and one-story building” prototype and changed over time, such as planar expansion and vertical growth.

2.2. Theoretical Basis: Self-Organization

Contemporary vernacular architecture is a group phenomenon involving the spontaneous development of local construction, an orderly process of self-organizing evolution [

7]. Self-organization theory gradually emerged after the 1960s, first recognized in physics and chemistry and then expanding into the social sciences and other fields. The theoretical cluster includes dissipative structure, synergy, catastrophe theory, hypercycle theory, fractal theory, and chaos theory. It is considered to be one of the universal laws of nature and society [

8]. Self-organization theory inspired the urban design works of Christopher Alexander and Ashihara Yoshinobu, among others, and was formally introduced into urban research by Juval Portugali, Peter M. Allen, and others in the late 1990s. The book

Notes on the Synthesis of Form presents an entirely new theory of design: the process of inventing things which display new physical order, organization, and form, in response to function. Christopher Alexander shows that such an adaptive process will be successful only if it proceeds piecemeal instead of all at once [

9]. Research related to the theory of self-organization in China began with exploration in the field of philosophy by many scholars, such as Zeng Guoping and Wu Tong of Tsinghua University, and has attracted attention of rural community researchers since 2007.

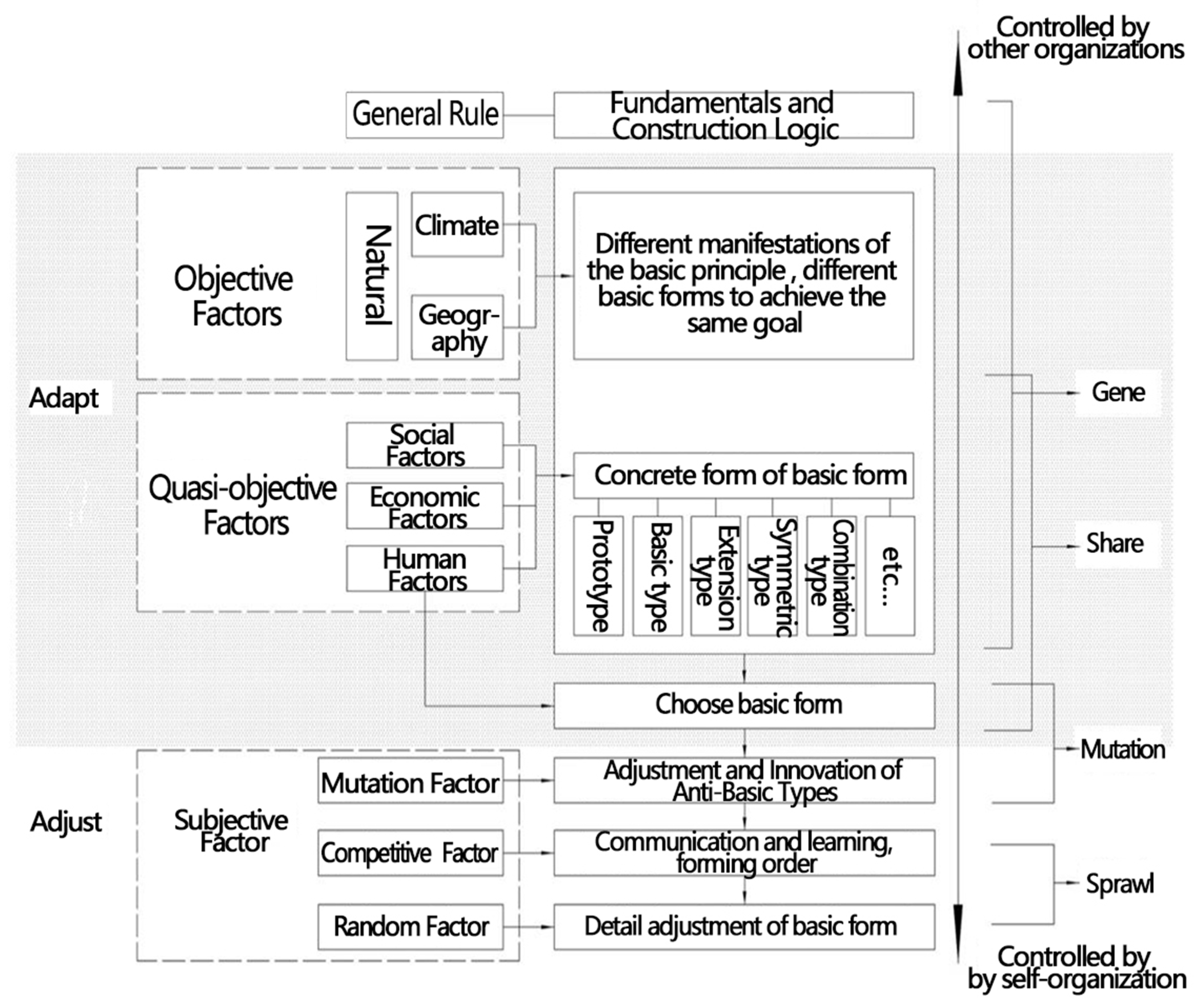

Chinese rural settlements are composed of a large number of independent units built by farmers, similar in structure to self-organizing systems. Constructing rural houses is directed by natural and geographical conditions, local construction policies, and land regulations. These external factors modify and limit the spontaneous development of rural areas. Vernacular architecture in northern Henan may be considered a self-organized system. (This logic system was proposed by Dr. Wei Duan in “Made in Xiaoshan—A Research of Spontaneously-built Houses in Southern Sands Area in Xiaoshan, Zhejiang Province”, an article published in 2015. A large number of relatively independent monomer samples form a system. These samples change from disorder to order, or from one order to another, without specific specified control. There are four steps to go through, including gene prototype, sharing, mutation, spreading, and then cycling. It constantly promotes the evolution of local new formal order [

10].) The controlled and spontaneously built phenomena express an organic composition of “bottom-up” and “top-down” development.

Figure 5 shows the generation of this locale’s vernacular architecture. A complex screening process is limited by several basic factors, constantly defined, and affected by both subjective and objective factors [

10].

In the process of self-organization, the system function and structure will start a process of accumulation from simple to complex when new organizations begin to appear. When individual elements are included in a system, the overall system must be more complex. More complex organizations provide new possibilities in time and space for evolution. The more interconnected organizations become, the more new functions emerge [

11]. Zhang Yongqiang applied the core principle of system self-organization theory to the research of urban space development in the research of urban space self-organization development, and discussed the internal mechanism of urban space self-organization development. Affected by social economy and other aspects, the purpose of individual construction behaviour is different. It is difficult to predict the development direction. However, the macro characteristic of a large number of individual constructions is regular [

12]. This spatial system experiences the interaction of various structures and functions and changes from disorder to order, from gradual change to mutation, making the system more stable.

Based on the principle of self-organization, the development of vernacular architecture can be summarized as including the following four processes: gene-sample prototype, shared neighbourhood communication, mutation—feature emergence, and sprawl—feature formation. (The concepts of self-organization theory in the field of architecture can be used to explain the phenomenon of rural community construction and rural spontaneous construction in China. The related concepts and expressions and these four main processes mainly refer to the research framework of Dr. Lu Jiansong of Tsinghua University and Zhou Lihong of Yunnan University on the topic of urban and rural spontaneous construction.)

3. Results

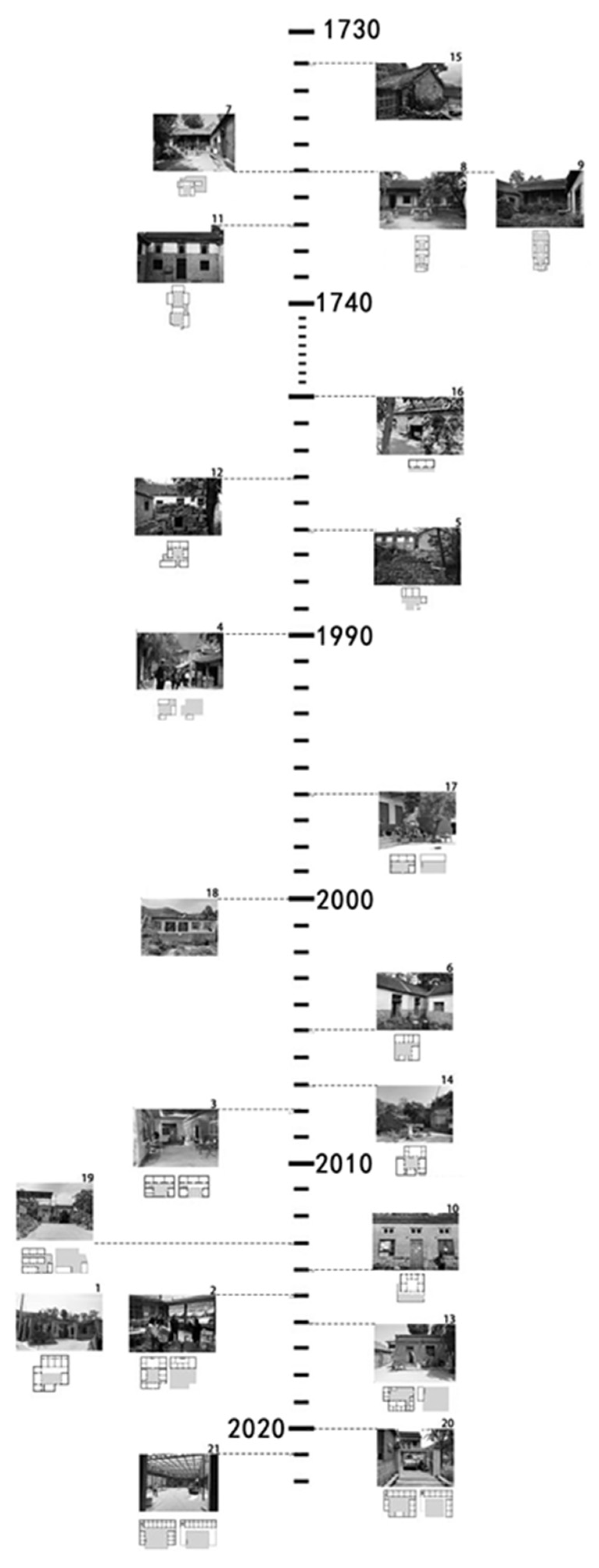

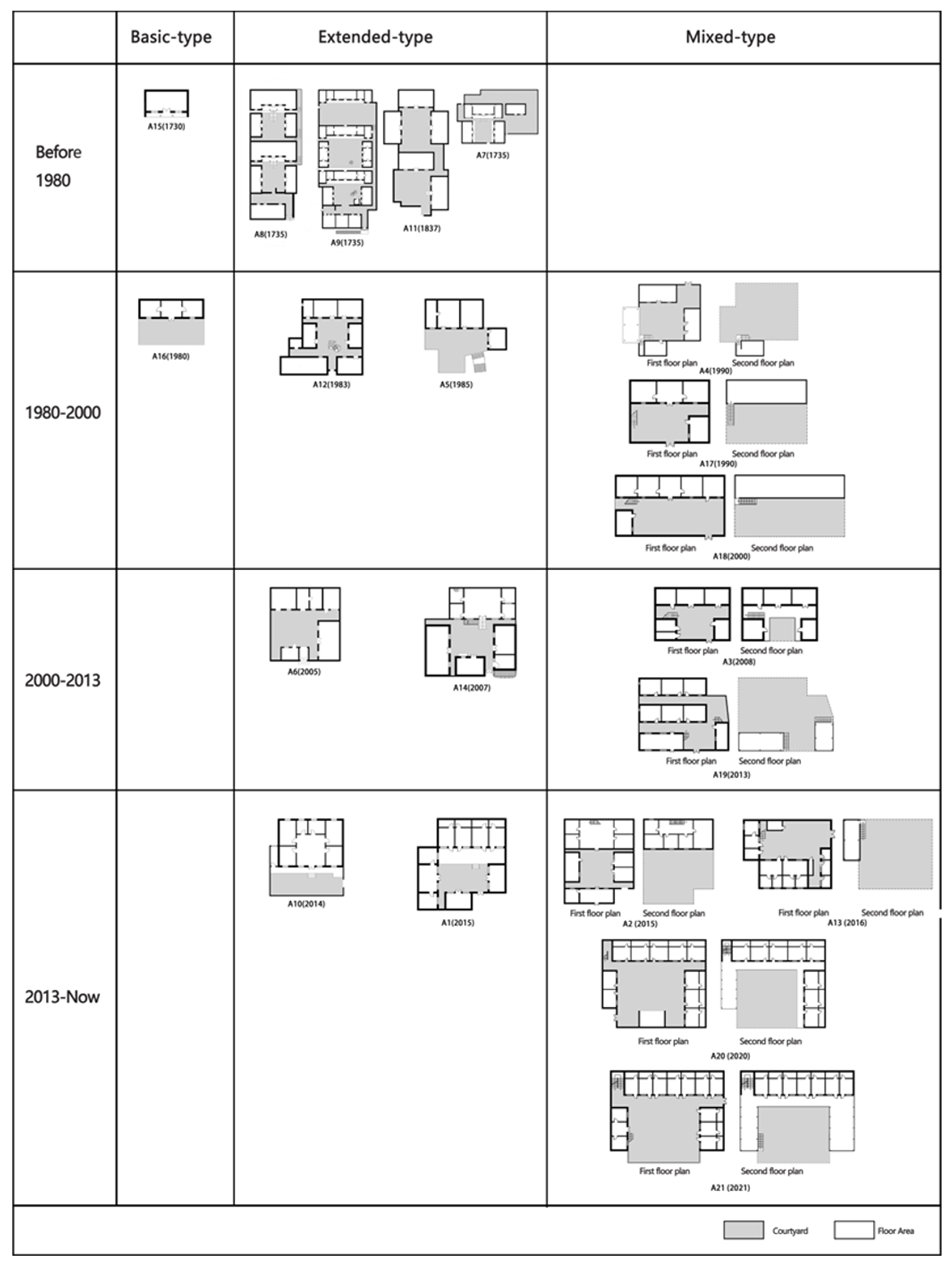

In order to study the evolution of vernacular architecture, this research analyses the survey samples in terms of time and space (

Figure 6). With the passage of time, these samples were reconstructed or expanded in different dimensions. The construction logic and evolution mechanism behind the morphologic changes of samples is worth in-depth study.

3.1. Gene: The Analysis and Interpretation of Spatial Types

Behind the complex appearance of the sample lies a consistent architectural typology. Each single building is arranged in a centripetal formation around the courtyard. Analysis discovered that the typology is controlled and influenced by a series of factors that evolved over nearly 40 years. This architectural evolution includes increased building heights and depths, the traditional three-bay pattern has been broken, and traditional buildings have transitioned from three-bay single buildings to courtyard-style complexes of buildings. Based on these factors, the samples can be divided into three types: basic, extended, and mixed (

Figure 7).

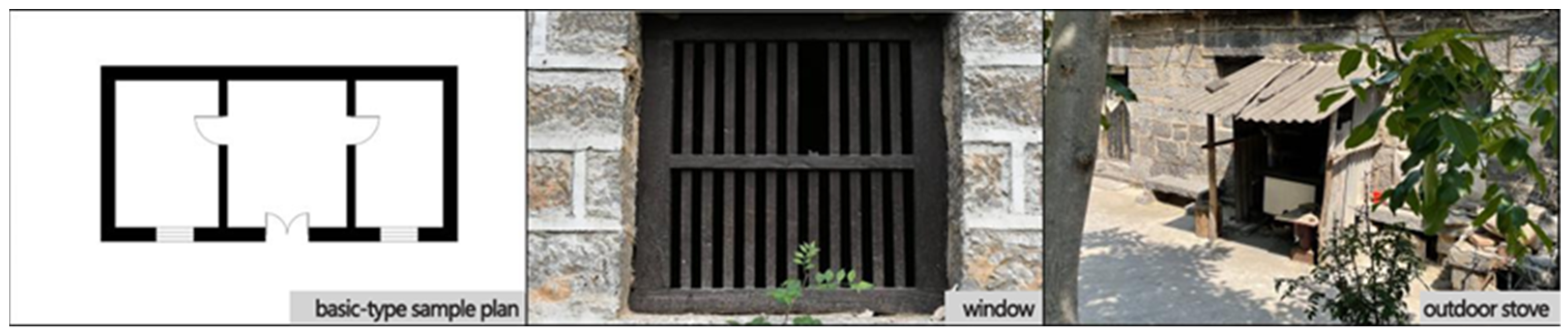

3.1.1. The Basic Type

The basic type of traditional buildings in the southern Taihang area originated from the shape of plan in straight lines, the most common style of rural buildings in the north [

13]. In order to meet the owner’s living needs, this type of building presents an axisymmetric structure with the main house as the centre and wing-rooms on both sides. The basic type of the samples studied are mostly single buildings, each of which comprises a three-bay house with a courtyard. Some canopies made of wood and slate have been built on both sides of the buildings, primarily used to store farm tools, firewood, and stoves. The basic type of samples has not yet formed courtyards with formal walls, but is enclosed by stacking stone pavements on the ground, which, combined with surrounding debris, have gradually taken the embryonic form of the courtyard. Building walls were constructed with the most readily available local stone, while the roofs are slate flat roof. There are few windows, with doors and windows being constructed with traditional wood (

Figure 8).

3.1.2. The Extended Type

The expanded type samples retained plan shapes of straight lines with a three-bay main house. Compared with the basic type, some auxiliary rooms arranged symmetrically on both sides of the main house began to appear. Cooking and storage are the general functions of the auxiliary spaces. This is the time when brick wall enclosed courtyards began to appear (

Figure 9).

Differences between the basic and expanded sample types are evident. The overall scale of the expanded types is large. The plan of the main house is always three-bay while in section the form closely resembles the basic type. Impacted by China’s reform and opening up, architectural style, building materials, and construction technology changed. Vernacular architecture at this stage has become more concise under the influence of modernist architecture. Brick–concrete structural systems began to appear. Later expanded types were affected by tourism development, spontaneously transforming some complexes into homestays. The depth of the main house and the number of internal rooms increased. At the same time, they began to make full use of the courtyard, setting up roofs in the courtyards to shelter outdoor dining from wind and rain.

3.1.3. The Mixed Type

A significant amount of mixed type rural dwellings appeared after 1985. Residents improvised by using flat roofs and courtyards to dry crops, a result of vigorous agricultural development. Staircases were attached to one side of the annex room, identifying a new trend of using the roof to expand vertically. The main house was also stretched horizontally from the traditional three-bay to five-bay and featured more windows. The ground of the courtyard was mostly paved with fair-faced concrete. Residents decorated it with flower pots or flower beds.

In the process of a series of rural renewal in China, many scenic villages have been converted into tourist villages in the southern Taihang area. The development of a mixed-type vernacular architecture intensified in this environment. The function of the building was transformed from the spiritual space of the family to a leisure homestay for tourists. Spatial types and building aesthetics also became more complicated [

14] (

Figure 10).

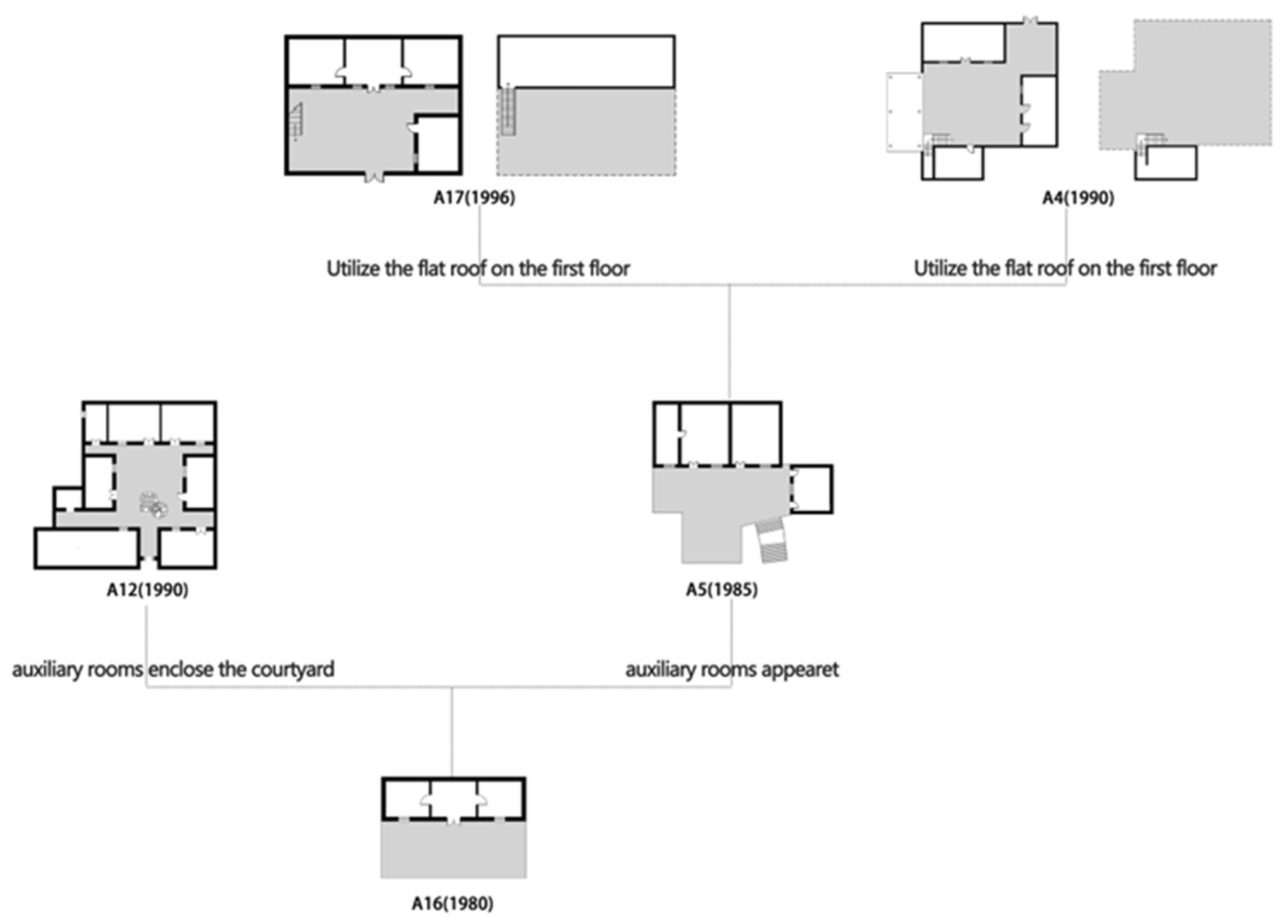

3.2. Sharing: The Growth and Development of Residential Structures

Although the physical manifestations of the above three types are quite different, their material mappings highlight the development trends of different times. Vernacular architecture is attractive, not for any remarkable appearances, but for the visible expressions of expansion, reconstruction, and new development. These expressions are also related to the development of local culture and the change of villagers’ living needs. Combine the basic type, extended type, mixed type, and time chronology sorted out above into an intergenerational relationship between different types from three dimensions of building plan, courtyard plan, and building facade to explore the relationship between vernacular architecture and geographical features.

3.2.1. Horizontal Stretching of The Plane

In the 1980s, China’s rural economic structure generally featured planting agriculture. Improving rural agricultural productivity was the main goal of the time. Therefore, the design of rural dwellings at this stage was intended to satisfy the daily life of the residents, while also assisting production. Farming principles of diligence and frugality were fully reflected in the samples at this stage and spaces within their vernacular architecture constructs were fully utilized. Residents could dry and store crops in their own courtyards after harvesting, facilitated by courtyards paved with fair-faced concrete flat roofs used to expand the drying space of the grain. Portions of the new wing-rooms were used for crop storage.

In the 1990s, after China’s reform and opening up, the first climax of dwelling construction was set off in the rural areas of China. This prompted a horizontal stretching of building plans, changing from the traditional “three bays” to “five bays”. Building materials were mainly bricks and wood. The building materials also changed from brick and wood to brick–concrete materials, a transition from local to modern [

15] (

Figure 11).

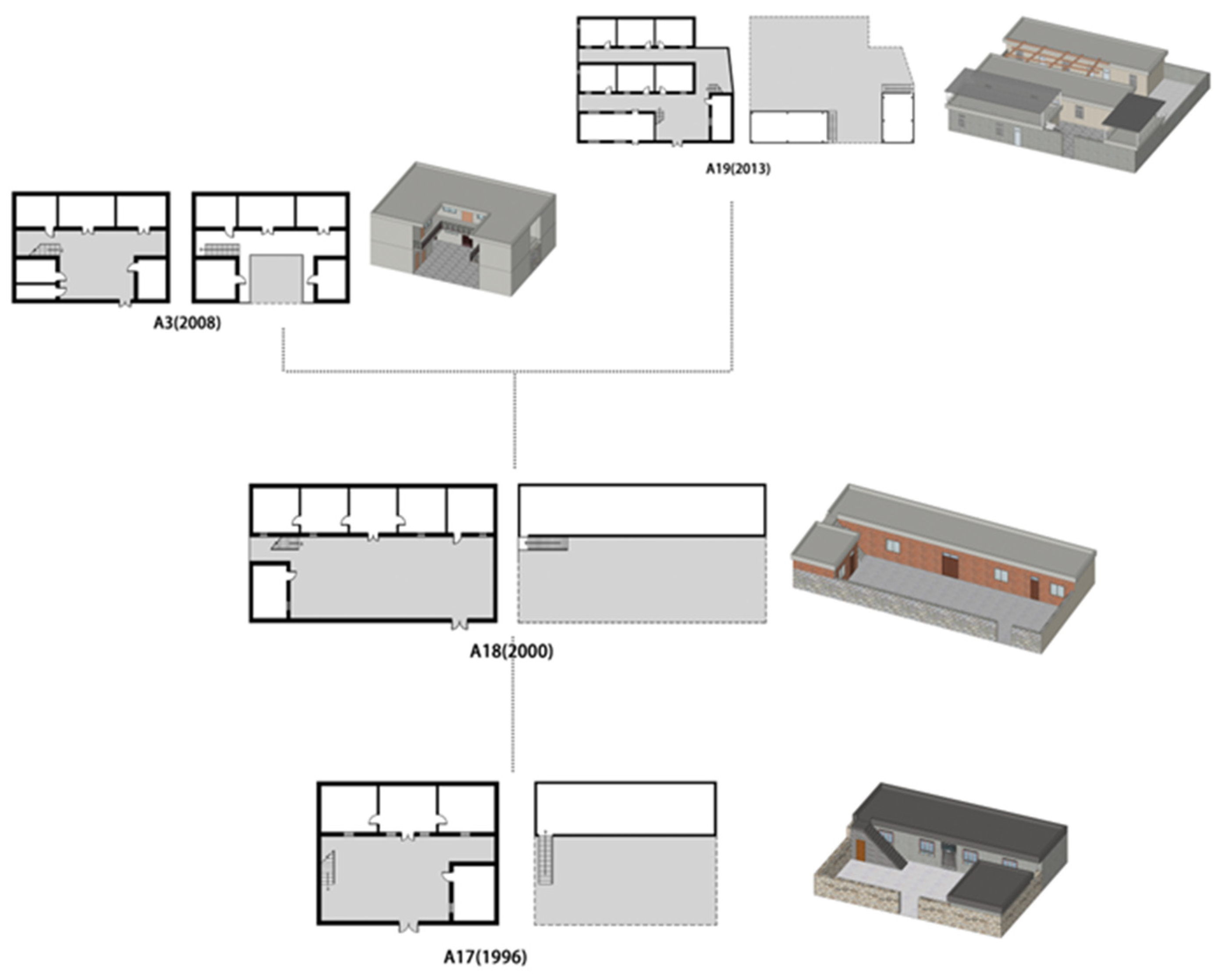

3.2.2. Vertical Growth of the Facade

Agricultural development requires funds and capital. With increased urbanization, more young people migrate to cities to work and settle, leaving the countryside with less economic power to promote development. Elderly residents remaining in rural areas choose to plant easy-care crops and manage the land extensively, deviating from officials’ goals of optimizing the allocation of rural land [

16]. Some villagers responded to the government’s call to expand rural tourism by converting their houses into hobby farms or homestays, altering traditional plan layouts. Rural residents constructed auxiliary rooms adjacent to the main houses to better accommodate tourist needs such as space for toilets, and interior planes also expanded as living spaces were further divided. The traditional family-centric housing model changed.

Vernacular architecture of this period extended vertically. Because of the restrictions of the Measures for the Implementation of the Land Administration Law in Henan Province, rural residents generally constructed low-rise buildings with three floors or less [

7]. Building facades featured characteristic tiles or wooden boards. Roofing materials changed from grey tiles to light blue glazed tiles. The flat roof eaves of some hobby farms were painted with colourful paint to attract attention. These new facades became the “face” of the hotel, requiring beauty and uniformity. Exaggerating the shape of the roof further attracted visitors’ attention.

Open courtyards evolved into outdoor restaurants for tourists. Simple scaffolds were built above some courtyards to protect visitors from the elements, while some courtyards were laid with ceramic tiles to enhance aesthetics on the groundplane. The courtyard too evolved from a traditional, core space for families into a subsidiary space prioritizing the needs of visitors (

Figure 12).

3.2.3. Diversified Development

With the issuance of the “Building the Beautiful Countryside” policy in 2013 and the “Action Plan to Promote the Quality and Upgrade of Rural Tourism Development (2018–2020)” by 13 departments, including the National Development and Reform Commission, rural tourism in the southern Taihang area saw significant growth. Operations for rural tourism diversified. Homestays and hobby farms grew in scale from small to large and the management is more sophisticated [

17].

Self-employed homestay operations expanded the depth of the main house and the division of interior space became more modular. Adjacent wing-rooms also increased spatially, functioning as guest rooms. Kitchens and storage rooms occupied the wing-rooms on the opposite side. Layouts of the courtyard were clearly divided, while giving attention to landscape design. For example, in the area closest to the kitchen, ceramic tiles were laid on the ground to provide a foundation for a sun board ceiling, defining the outdoor dining space. Flowers and greenery were planted to create a quiet environment near the guest rooms. Some homestays made full use of vertical space, setting up canopies on the flat roofs and arranging tables and chairs to form outdoor restaurants with better views.

Collectively run homestays and hobby farms are managed by the members of the village committee and improved upon by collective investment. Tourism income is also shared by the collective. These types of homestays are often larger with clearly defined partitions and increased functionality, and prioritize convenience of service and facilities. For example, guest rooms offer separate bathrooms and the furniture will be uniformly customized. Indoor kitchens and outdoor stoves are arranged in an orderly manner (

Figure 13).

3.3. Mutation: The Evolution of the Dwelling

Diversified development has randomness, which is accomplished through a large number of mutations. Different mutations gradually form a characteristic. Later, these characteristics are generally recognized and developed into a consensus. This is also an important step in connecting gene sharing and spreading in self-organization theory.

On the eve of mutation, there are many transformations in the function of vernacular architecture in the southern Taihang area. A large number of buildings have transformed from residences to homestays. These transformations can be summarized in the following four parts:

Transition from the main house to the hall;

Simultaneous appearance of traditional and modern kitchen;

Changes between bedrooms and guest rooms;

Renewal of the courtyard space.

3.3.1. Transition from the Main House to the Hall

During the period of China’s reform and opening up, the characteristics of Western living rooms infiltrated into the main house. Western living rooms are generally family public spaces, allowing for communication and interaction, and exuding a more relaxed atmosphere. As rural tourism developed and dwellings transformed into homestays, the living room spaces were converted into halls for receiving guests. Service desks and wine cabinets appeared in lobbies, and sofas and seating were added to the spaces. The private, family spiritual spaces of traditional dwellings gradually transformed into an open public space (

Figure 14).

3.3.2. Simultaneous Appearance of Traditional and Modern Kitchen

With higher rates of kitchen usage, dwellings-turned-homestays require elevated kitchen standards. Modern kitchens revised spatial layouts, a more hygienic lifestyle was introduced, and new fuels replaced the traditional [

18]. Indoor kitchens became more beautiful and comfortable, dramatically different from the traditional, dimly lit kitchens. Walls were repainted or tiled for easy cleaning. Factory-produced integrated worktops, along with built-in storage cabinets installed above the worktops, reflect the conveniences brought by the age of mechanization. Liquefied gas, pipeline gas, and induction cookers replaced traditionally used firewood. Even the layout of the outdoor stove seems more orderly. The traditional flame that has been burning for thousands of years in rural China is getting weaker and weaker on the stainless-steel stove top of the modern kitchen (

Figure 15).

3.3.3. Changes between Bedrooms and Guest Rooms

Changes in bedroom layouts also reflect an evolving vernacular architecture in rural China. The layout of modern bedrooms is no longer dominated by the traditional hierarchical distribution system, but changed more flexibly. These rooms are used to entertain tourists during the peak tourism season and serve as spare bedrooms for homeowners during the off-season. The decoration of the bedroom has been transformed to be more comfortable, and the layout has been adjusted to two beds. Guest rooms have become the rooms with the largest area and the most complete infrastructure (

Figure 16).

3.3.4. Renewal of the Courtyard Space

The many functions of the courtyard in traditional, agriculture-dominant southern Taihang villages meant haphazard and chaotic spatial arrangements, more often based on usage and need than aesthetics or order. The shift from agricultural economy to a tourism economy, the advancement of science and technology, and the elimination of traditional production tools all were factors leading to a separation and expansion of the courtyard’s functional space [

19]. With improvements in agricultural science and technology, and the influence of tourism economy, villagers began to seek more multi-dimensional development of courtyards to meet changing needs and offer an enriched tourist experience. The vertical space is fully used includes the canopies built on roofs, the groundscape and greenery [

20] (

Figure 17). From the 1980s to 2005, the rural dwellings were mainly expanded on the homestead, and the additional functions were mostly storage. From 2005 to 2013, the floor area almost filled the homestead and the space was expanded to the roof. The functional space was transferred, such as moving plant drying to the roof to leave ample courtyard space. After 2013, canopies began to appear. This provides a place for tourists to communicate, which also makes the courtyard gradually transform into a public living room and the roof gradually becomes a viewing platform.

3.4. Sprawl—The Formation of Residential Characteristics

Spontaneous mutation and spread of a certain scale of samples establish the characteristics of vernacular architecture. When a characteristic is established, it will become a new order and gradually spread, so as to be accepted by a wider range of owners. This is sprawl. (The individual samples coordinate with each other, and finally reach a consensus in some aspects. This consensus based on independent decision-making is called “order” [

21].)

3.4.1. The Emergence of Self-Built Homestay Features

Emergence is a process from simple to complex. The foundation of complex systems can be established by a few rules. System units will continue to innovate on the basis of these rules and gradually evolve into new features, enriching the original simple system. For example, the emergence of a canopy. Traditional buildings have ample interior space, but limited courtyard space. Many homestays are innovated by making full use of the flat roofs to build single-layer canopies made of coloured steel. Adding tables and chairs (

Figure 18) created well-lit and well-ventilated outdoor restaurants within the areas’ beautiful, natural scenery [

22].

Similarly, canopies ease expansion restrictions of the homestead’s boundaries. To make full use of the courtyard, residents spontaneously build canopies. The space under the canopy is both an extension of the indoor space and an outdoor space with communication properties. Canopy materials are generally polycarbonate hollow sheet or PP plate sheet to ensure adequate daylighting and rain proofing. Some homestays use other materials to divide the courtyard space. For example, sample No. 3 of Xiaodianhe Village constructed a coloured steel canopy at the courtyard entrance and a flower stand next to the guest room.

3.4.2. Consensus in Decision-Making

Various system units coordinate with each other in the context of stable development, reaching agreement on certain practices. This process is called consensus. Consensus establishes a stable characteristic under human manipulation, gradually transforming into regional genes [

21]. Generally speaking, building details, such as roof, decoration, plaque, canopy, and so on, are easier to establish a stable characteristic. If a characteristic is to develop steadily, it requires repeated experiments of individuals until a basic consensus is reached [

23]. Therefore, the evolution of the space archetypes mentioned above is very slow and there have been only a few types in the last 30 years. However, there have been frequent changes in roof styles, window styles, and exterior wall colours and materials. All of this is easily affected by the external environment. For example, climate conditions, construction techniques, and energy utilization in the southern Taihang area are the main factors causing the simultaneous appearance of indoor kitchens and outdoor stoves.

3.4.3. Stable Characteristics

Many firewood stoves have been kept in dwellings built before 1985. Because wood stoves are large and require space to store firewood indoor, kitchens were particularly crowded and messy, made worse by poor lighting and inadequate ventilation. Therefore, many residents chose to build an additional stove outdoors (

Figure 19). Because of limitations on fuel and construction techniques, outdoor stoves were generally small and made of bricks for daily use.

After 1985, new buildings in the southern Taihang area retained the custom of outdoor cooking while keeping the original indoor kitchen. Stoves have changed with the widespread use of coal and gas and the use of wood stoves and fire ponds is decreasing. The result is a more compact kitchen space. The outdoor stove space has also become smaller as residents take to coal stoves and boilers for their convenience. Indoor kitchens have been unable to meet the needs of large numbers of tourists. Small-scale homestays have chosen to update the indoor and outdoor kitchen equipment, while large-scale homestays build outdoor kitchens in the courtyard by building canopies and walls systematically. The layout and the placement of the stove have also become more organized.

Although the location of the kitchen has changed, from auxiliary room to outdoors, plus the simultaneous appearance of the two types in recent years, the significance of the kitchen to the life of the villagers has not changed. The location of the kitchen stove in the building is not only a direct reflection of the lifestyle and needs of the villagers, but also a material reflection of the development of the times.

4. Discussion

Vernacular architecture in northern Henan is an integral part of characterizing the form of the landscape in the rural areas of central China. It is one of the clues to understanding the local culture, as important a clue as any other. A study of the formation and transformation of vernacular architecture will “leak” local culture and its transformations. (What needs to be acknowledged here is that vernacular architecture and settlements, as a single clue, cannot reflect the full picture of vernacular architecture in northern Henan, and may even be misleading. Therefore, the term “leak” is used here rather than “reflect”.) Analysis through such a lens can lead us to make important inferences about the evolution of Chinese rural vernacular architecture in recent years.

Contemporary vernacular architecture in northern Henan follows the self-organizing mechanism of spontaneous building. It is actually a spontaneously constructed group phenomenon, in which a system composed of a large number of relatively independent units changes from disorder to order, or from one kind of order to another without specific designated control. This is a process of evolution. The four stages of its process—gene, sharing, mutation, and spread—reciprocate and continuously drive the evolution of a new local formal order. The mechanism of action is represented by the figure below (

Figure 20). (For a single sample, its micro-change process is complex and changeable, but certain self-organization rules can be found from the spontaneous group phenomenon [

10]. Through the analysis and induction of the article, it is found that the changes of vernacular architecture in the Xinxiang area are like biological evolution. The mutual influence of different elements makes the construction of buildings change. The mutation conducive to residents’ living and social development is widely recognized and spread, then determines the general appearance of local buildings.)

(1) The controlled and broad-spectrum genes, on the material level, are a series of spatial prototypes at the scale level, which together constitute the morphological basis of the local human settlement environment. They are also the basis for the diversity and difference of local vernacular architectures.

(2) The process of making decisions through communication between neighbours can be called “short-range communication”, which is also the basic mode of gene sharing and dissemination in self-organizing systems. The decision-making of each sample is fast and parallel. There is no priority between decision-making and execution, and the order of actions is often random.

(3) The generation of new regional genes is not entirely caused by the rational control of influencing factors but is a non-predetermined random emergent process. “Mutation” is caused by two mechanisms, namely emergence and competition.

(4) Each individual sample coordinates with each other. Eventually a consensus will be reached with regard to approach. This consensus, based on the independent decision-making of the individual, is a stable feature called preface [

22]. After the characteristics are formed, they will be converted into regional genes.

5. Conclusions

Although an attempt is made to explain the process of generation and evolution of contemporary vernacular architecture types in northern Henan through self-organization theory, it is undeniable that there is a lack of investigation into the subjective needs and initiative of builders in the period. It is true that certain self-organization laws can be found from spontaneous group phenomena but, for a single sample, the microscopic decision-making process is complex and difficult to generalize. However, through the above research in this paper, we can find that the generation mechanism of contemporary vernacular architecture is an interactive process of other-organization and self-organization. It is an organic combination of “bottom-up” and “top-down”. Neither architects nor planners are the dominant forces in the generation of urban and rural settlements. After understanding a series of space prototypes, the owner can independently design his own residence according to the environmental conditions. A large number of self-built houses will come together to form a proper settlement with self-optimizing ability.

During the construction process, the residents assume different roles. They are designers, builders, and users. Residents build or transform their buildings according to their own needs. The way of building construction is closely related to the lifestyle of residents. Spontaneous building is an immediate response to the social environment. Buildings in different regions directly reflect the impact of changes in policy, economy, technology, and materials on architecture. It also shows the process of building changing with time. This is the regionality of vernacular architecture.

Vernacular architecture is the embodiment of sustainable development, innovation, and culture. It preserves the individual feelings of residents and the overall appearance of the village, and creates comfortable living space. In order to bring more possibility to the renewal of buildings in the southern Taihang area, the spontaneous construction activities should maintain communication with the external environment and establish a reasonable planning system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.D., X.Y., T.Z. and H.C.; Data curation, X.Y.; Formal analysis, X.Y.; Funding acquisition, W.D.; Investigation, X.Y.; Methodology, W.D.; Project administration, W.D.; Resources, X.Y.; Software, X.Y.; Supervision, W.D.; Validation, T.Z.; Visualization, X.Y.; Writing—original draft, X.Y.; Writing—review and editing, T.Z. and H.C., W.D. and X.Y. designed the study, surveyed, mapped, and analysed samples, and wrote the draft paper; T.Z. and H.C. led the manuscript revision and modification, and helped improve other parts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “National Natural Science Foundation of China” (No. 52208005), “Beijing Social Science Foundation” (No. 22GLC063).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Xinyu Yang, Ting Zhang and Haoxian Cai for their strong support for this research work. The authors are also heartily grateful to Haoxian Cai for his constructive comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Isham, N.M.; Brown, A.F. Early Rhode Island Houses: An Historical and Architectural Study; Preston & Rounds: Preston, UK, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Upton, D.; Vlach, J.M. Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture; University of Georgia Press: Athens, Georgia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Liangyong, W. The modernization of vernacular architecture and the regionalization of modern architecture—On the road of exploration of new architecture in China. Huazhong Archit. 1998, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liangyong, W. Generalized Architecture; Tsinghua University Publishing House Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, T.; Cromley, E.C. Invitation to Vernacular Architecture: A Guide to the Study of Ordinary Buildings and Landscapes; University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2005; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Yawei, L. Study on Traditional Settlement and Residential Buildings in the Southern Taihang Mountains of Henan Province. Master’s Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jiansong, L. Contemporary Value of Architectural Regionalism Studies. Archit. J. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, K.W.; Haken, H. An Introduction. Nonequilibrium Phase Transitions and Self-Organization in Physics, Chemistry, and Biology. In Synergetics, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. Notes on the Synthesis of Form; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D. Made in Xiaoshan A Research of Spontaneously-built Houses in Southern Sands Area in Xiaoshan, Zhejiang Province. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, W. Outline for Self-organizing Methodology. J. Syst. Dialectics 2001, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yongqiang, Z. Space ResearchII: Resesarch on Self-Organization of Urban Space Development; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, S.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L. A Preliminary Study on the Features of Defensive Traditional Villages in Taihang Mountain Area in Northern Henan: Taking the Ancient Architectures of Xiaodianhe Village in Weihui as an Example. J. Green Sci. Technol. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Linna, M. Protection and Development Research of Xiaodianhe Traditional Village under the Prospective of Cultural Inheritance. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, Chuna, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L. Cong Huotang Dao Tingtang 从 “火塘” 到 “厅堂” [From Huotang to Tingtang]. Master’s Thesis, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Min, L.J.a.J. Protection and Development Research of Xiaodianhe Traditional Village under the Prospective of Cultural Inheritance. Archit. J. 2009, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Yang, Q.-Y.; Su, K.-C.; Yin, W.; Wang, W.-X.; Zhang, R.-R. lmpact of the Development of Rural Bed-and Breakfast Business on the Changes of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital: A Perspective of Rural Revitalization. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 43, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C. System Structure and Dynamic Mechanism of Rural Homestay Settlement Development: Taking Jiaju Tibetan Village in Danba County of Sichuan Province as Example. Areal Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Qunqun, T. Study on Rural Characteristics under the Background of Rural Revitalization: A Case Study of Rural Spatial Layout and Characteristic Architectural Elements in Minhang District, Shanghai. Rural Revital. 2020, 38, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Xinyu, C. Evolution and Influence Mechanism of Rural Courtyard Spatial Layout. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Taian, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Study on the Renewal Design of Rural Settlements Guided by Tourism Development—Take Yaojialing Village of Zixi County as an Example. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Technology, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, H. Erfolgsgeheimnisse der Natur Synergetik: Die Lehre vom Zusammenwirken; Shanghai Translation Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Upton, D. Pattern books and professionalism: Aspects of the transformation of domestic architecture in America, 1800–1860. Winterthur Portf. 1984, 19, 107–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Number of international tourists in Xinxiang 2005–2019.

Figure 1.

Number of international tourists in Xinxiang 2005–2019.

Figure 2.

Number of domestic tourists in Xinxiang 2005–2019 (figure source: “Development Plan of Cultural Tourism and Health Care Industrial Zone of the southern Taihang in Xinxiang” collated and redrawn).

Figure 2.

Number of domestic tourists in Xinxiang 2005–2019 (figure source: “Development Plan of Cultural Tourism and Health Care Industrial Zone of the southern Taihang in Xinxiang” collated and redrawn).

Figure 3.

Research location (figure source: drawn by authors based on relevant information).

Figure 3.

Research location (figure source: drawn by authors based on relevant information).

Figure 4.

Vernacular architecture in Village Guoliang, Hankou, Zhangsigou, and Xiaodianhem (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 4.

Vernacular architecture in Village Guoliang, Hankou, Zhangsigou, and Xiaodianhem (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 5.

The process of sample generation of vernacular architectures (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 5.

The process of sample generation of vernacular architectures (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 6.

Time chronology of vernacular architecture in the southern Taihang Area (figure source: drawn by authors based on relevant information).

Figure 6.

Time chronology of vernacular architecture in the southern Taihang Area (figure source: drawn by authors based on relevant information).

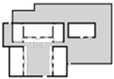

Figure 7.

Distribution of architectural space types (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 7.

Distribution of architectural space types (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 8.

Sample 16 of the basic type (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 8.

Sample 16 of the basic type (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 9.

Sample 14 of the expanded type (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 9.

Sample 14 of the expanded type (figure source: photographed by authors).

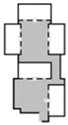

Figure 10.

Sample 20 of the mixed type (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 10.

Sample 20 of the mixed type (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 11.

Horizontal stretching of the plane (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 11.

Horizontal stretching of the plane (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 12.

Vertical growth of the façade (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 12.

Vertical growth of the façade (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 13.

Diversification of the sample (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 13.

Diversification of the sample (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 14.

Comparison of main room and hall (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 14.

Comparison of main room and hall (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 15.

Comparison of traditional and modern kitchens (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 15.

Comparison of traditional and modern kitchens (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 16.

The comparison between the bedroom of traditional dwelling and homestay (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 16.

The comparison between the bedroom of traditional dwelling and homestay (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 17.

The evolution of the courtyard (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 17.

The evolution of the courtyard (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 18.

Self-built canopies (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 18.

Self-built canopies (figure source: photographed by authors).

Figure 19.

Evolution of the fire stove in the courtyard (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 19.

Evolution of the fire stove in the courtyard (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 20.

The generation mechanism of contemporary vernacular architecture in northern Henan (figure source: drawn by authors).

Figure 20.

The generation mechanism of contemporary vernacular architecture in northern Henan (figure source: drawn by authors).

Table 1.

Summary of site selection for traditional villages.

Table 1.

Summary of site selection for traditional villages.

| Village | Landform Type | Elevation (m) | Slope | Position towards | River |

|---|

| Shuimo | Valley | 670 | 7.0% | Northeast | With |

| Dinggou | Valley | 700 | 15% | Southwest | Without |

| Tuchi | Valley | 640 | 12.7% | South | With |

| Zhangsigou | Valley | 580 | 10.8% | Southwest | Without |

| Guoliang | Mountainside | 1130 | 20.1% | Southwest | With |

| Dingzhuang | Basin | 81 | 5.0% | Southwest | With |

| Xiaodianhe | Basin | 260 | 8.7% | Southeast | With |

| Zhaoyao | Basin | 320 | 5.6% | Southwest | Without |

| Hankou | Valley | 580 | 12.2% | Southwest | With |

| Liyu | Valley | 370 | 10.2% | Southwest | With |

| Ligou | Valley | 340 | 6.0% | Southwest | Without |

| Qiwangzhai | Valley | 940 | 15.2% | Southwest | With |

Table 2.

Summary of sample information (source: drawn by authors).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).