Relating Spatial Quality of Public Transportation and the Most Visited Museums: Revisiting Sustainable Mobility of Waterfronts and Historic Centers in International Cruise Destinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Accessibility

2.2. Potential Use of PT

3. Methodology

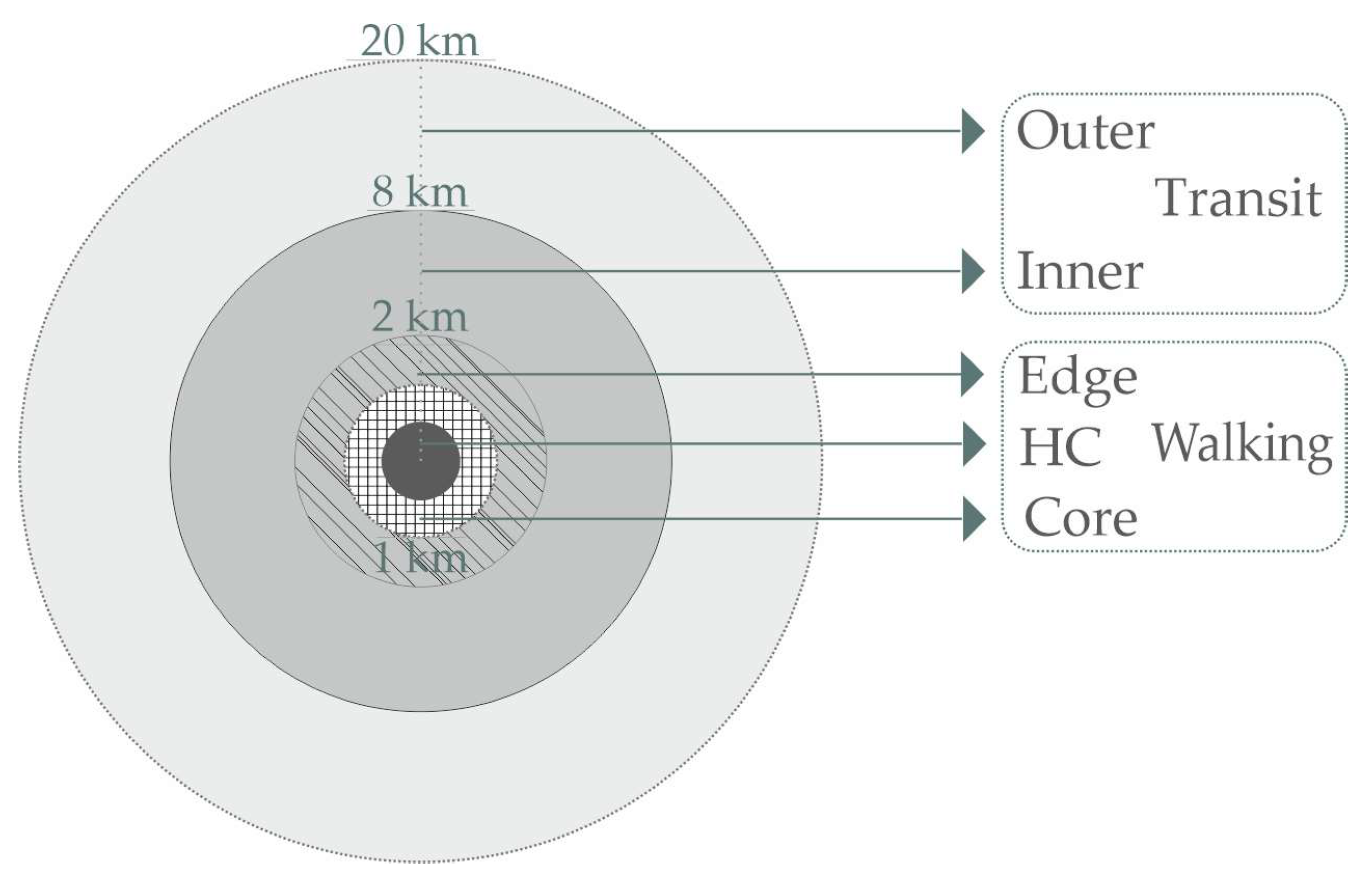

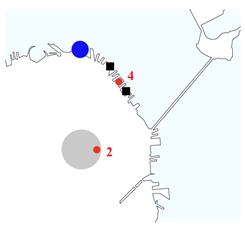

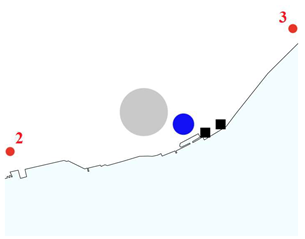

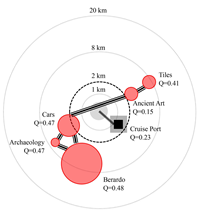

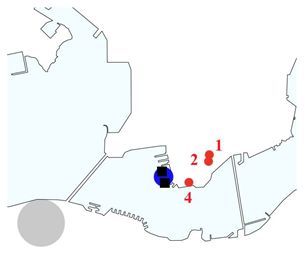

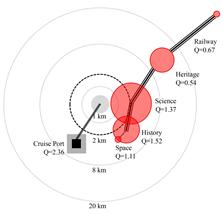

3.1. Spatial Model of Tourist Resources and Topological Analysis of PT

3.2. Assessment of the Potential Objective Quality of PT Connections

3.3. Selection of Case Studies

4. Results

4.1. Relevance of the Cruise Activity in the Case Studies

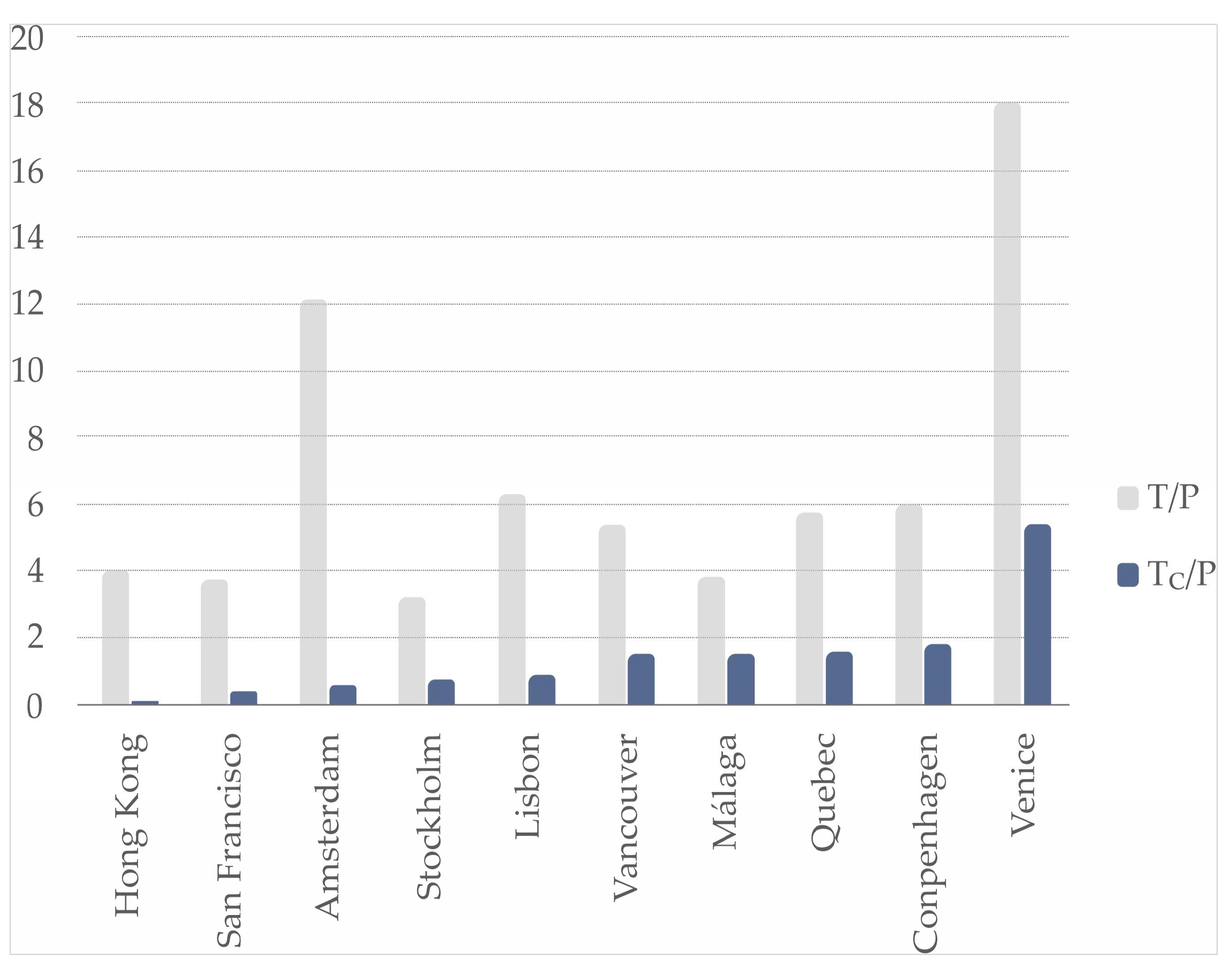

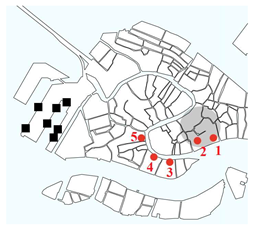

4.2. Degree of Spatial Centrality

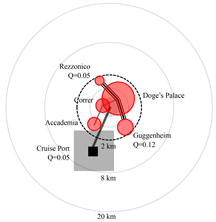

4.3. Accessibility and Potential Quality of Transport Systems

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Measures to Improve the Cruise Terminal

- Improving information to cruise tourists. Most of the PT websites consulted are at least in the native language and English (NL = 2) and with a specific section for tourists (NP = 1). However, there is a total lack of “intermodal transport ticket and access museum card”. The option of buying that combined ticket online is recommended so that cruise tourists do not have to exchange money and physically purchase the ticket. This would increase the Fi indicator by 30%. It is a measure implemented in Amsterdam and associated with museums with a high number of peripheral visitors to the historic centers. If that were not possible, greater information on the use of PT at the destination should be available at the cruise terminal and it should be easier to purchase public transport and tourist tickets by e-payments;

- Improving connection between the cruise terminal and historic center or transport station. The cruise terminal should be connected to the historic center (in the centralized model) or with a subway/bus station (in the decentralized model) by electric or zero-emission bus (at least during the cruise high season) or shared bike/e-bikes. Shared e-bikes would facilitate their use among older people, which could improve the indicator to Fe = 1 and that would double the Q value. This measure coincides with the strategies developed by an urban system of soft mobility pathways for pedestrians and bicycles to connect the historic center with the waterfront [58].

6.2. Measures to Improve the Objective Quality of PT

- Creating new museums, both close to the urban waterfront or to transport stations. The development of new museums in the urban waterfronts near to the cruise terminal, as is the case in Malaga, Quebec, San Francisco and Hong Kong, that have museums or floating museums (historic ships). Establishing new museums in subway or train stations (or very close to them) would facilitate them being visited by cruise tourists as they are places with great urban accessibility, as would setting up new museum clusters near to existing subway lines, e.g., scientific museums near to universities with subway stops, such is the case of Hong Kong;

- Analyzing the feasibility of conventional means of transport fostering the tourist experience particularly associated to the tram, train (the existence of many abandoned tracks near to the ports should be noted). Similar to the proposal for the reuse of disused railway lines for pedestrian and cycle path developed in proposals for sustainable mobility in urban waterfronts [18]. Or, following Venice’s example, creating ferry or small tourist boat lines running between the cruise terminal and waterfront heritage resources or museums would allow cruise passengers to discover the city and explore outside the historic center. In this regard, some authors [60] have concluded that the development of a ferry line as a formula for public transport in port areas increases the accessibility of the neighborhoods it connects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

| City | Transport | Web | Accessed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malaga | Bus | https://www.emtmalaga.es/ | 24 November 2019 |

| Quebec | Bus | https://www.rtcquebec.ca/ | 24 November 2019 |

| Copenhagen | Train | https://www.dsb.dk/ | 24 November 2019 |

| Tram/Subway | https://m.dk/ | 24 November 2019 | |

| Lisbon | Tram/Subway | https://www.carris.pt/ | 24 November 2019 |

| Hong Kong | Tram/Subway | https://www.mtr.com.hk | 24 November 2019 |

| Stockholm | Tram/Subway | https://sl.se/ | 24 November 2019 |

| Bus | https://sl.se/ | 24 November 2019 | |

| Amsterdam | Tram/Subway | https://en.gvb.nl/ | 24 November 2019 |

| Venice | Ferry | https://actv.avmspa.it/it | 24 November 2019 |

| San Francisco | Bus | https://www.sfmta.com/ | 24 November 2019 |

| Vancouver | Bus | https://www.translink.ca/ | 24 November 2019 |

References

- Wojtowicz-Jankowska, D. Museums of Gdansk-Tourism Products or Signs of Remembrance? IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 042010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. Gazing from home: Cultural tourism and art museums. Ann. Touris. Res. 2011, 38, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, S.; Davidson, L.; Mondher, S. Capital city museums and tourism flows: An empirical study of the museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 554–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B. A comparative study of international cultural tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2004, 11, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, F.; Lu, L.; Yu, P. The spatial agglomeration of museums, a case study in London. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Manca, F.; Nielsen, T.A.S.; Prato, C.G. Intentions to use bike-sharing for holiday cycling: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rocca, R.A. Soft Mobility and Urban Transformation: Some European Case Studies. TeMA 2008, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paananen, K.; Minoia, P. Cruisers in the City of Helsinki: Staging the mobility of cruise passengers. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juschten, M.; Hössinger, R. Out of the city–but how and where? A mode-destination choice model for urban–rural tourism trips in Austria. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Miravet, D. The determinants of tourist use of public transport at the destination. Sustainability 2016, 8, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Klähn, D.-T.; Hall, C.M. Tourist use of public transport at destinations—A review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.; McKercher, B. Modeling tourist movements: A local destination analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Kosonen, L.; Kenworthy, J. Theory of urban fabrics: Planning the walking, transit/public transport and automobile/motor car cities for reduced car dependency. Town Plan. Rev. 2016, 87, 429–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cantis, S.; Ferrante, M.; Kahani, A.; Shoval, N. Cruise passengers’ behavior at the destination: Investigation using GPS technology. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Medina, B.; Rosa-Jiménez, C.; Andrade, M.J. Potential of public transport in regionalisation of main cruise destinations in Mediterranean. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, C.; Sgambati, S. Active mobility in historical centres: Towards an accessible and competitive city. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skayannis, P.; Goudas, M.; Rodakinias, P. Sustainable mobility and physical activity: A meaningful marriage. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 24, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravagnan, C.; Rossi, F.; Amiriaref, M. Sustainable Mobility and Resilient Urban Spaces in the United Kingdom. Practices and Proposals. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morfoulaki, M.; Agathos, M.; Myrovali, M.; Konstantinidou, M.N. Willingness of Cruise Tourists to Use Pay for Shared and Upgraded Sustainable Mobility Solutions: The Case of Corfu. In CSUM 2020. Adv. Mobil. Serv. Syst. 2021, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurs, K.T.; van Wee, B. Accessibility evaluation of land-use and transport strategies: Review and research directions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helle, V.; Paananen, K.; Viinikka, A. Accessibility to Nationally Important Museums. In Analysing Multimodal Accessibility and Mobility in Urban Environments; Salonen, M., Tenkanen, H., Toivonen, T., Eds.; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2015; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, O. Spatial equity and cultural participation: How access influences attendance at museums and galleries in London. Cult. Trends 2016, 25, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, D.T. Tourism and Transport: Modes, Networks and Flows; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2007; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K.; Schofield, P. An investigation of the relationship between public transport performance and destination satisfaction. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Tamakloe, R.; Lee, S.; Park, D. Exploring the topological characteristics of complex public transportation networks: Focus on variations in both single and integrated systems in the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’agata, R.; Gozzo, S.; Tomaselli, V. Network analysis approach to map tourism mobility. Qual Quant. 2013, 47, 3167–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J.; Bi, Y. Determinants of collective transport mode choice and its impacts on trip satisfaction in urban tourism. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 94, 103094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Klähn, D.-T.; Gerike, R.; Hall, C.M. Visitor users vs. non-users of public transport: The case of Munich, Germany. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslauer, E.; Delmelle, E.C.; Keul, A.; Blaschke, T.; Prinz, T. Comparing Subjective and Objective Quality of Life Criteria: A Case Study of Green Space and Public Transport in Vienna, Austria. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 124, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, L.H.P.; Fortià, M.F.; Canals, C.S.; Marimon, F. Service quality assessment of public transport and the implication role of demographic characteristics. Public Transp. 2015, 7, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivková, I. Evaluation of Quality Public Transport Criteria in Terms of Passenger Satisfaction. Transp. Telecommun. 2016, 17, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugion, R.G.; Toni, M.; Raharjo, H.; Di Pietro, L.; Sebathu, S.P. Does the service quality of urban public transport enhance sustainable mobility? J. Clean Prod. 2018, 174, 1566–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, J.; Jian, M. Understanding Visitors’ Responses to Intelligent Transportation System in a Tourist City with a Mixed Ranked Logit Model. J. Adv. Transp. 2017, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajada, T.; Titheridge, H. The attitudes of tourists towards a bus service: Implications for policy from a Maltese case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 4110–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulley, N.; Balcombe, R.; Mackett, R.; Titheridge, H.; Preston, J.; Wardman, M.; Shires, J.; White, P. The demand for public transport: The effects of fares, quality of service, income and car ownership. Transp. Policy. 2006, 13, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhado, A.C.M.; Rothfuss, R. Transporting 2014 FIFA World Cup to sustainability: Exploring residents’ and tourists’ attitudes and behaviours. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2014, 5, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Filep, S.; Moyle, B. Movement in tourism: Time to re-integrate the tourist? Ann. Touris. Res. 2021, 91, 103199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B. The role of the transport system in destination development. Tourism Manage. 2000, 21, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürkop, D.; Gross, S. Tourist Cards–Experiences with Soft Mobility in Germany’s Low Mountain Ranges. In Conference Proceedings of BEST EN Think Tank XII.; Tiller, T.R., Ed.; University of Technology Sydney: Sidney, Australia, 2012; pp. 318–325. [Google Scholar]

- Le-Klähn, D.-T.; Hall, C.M.; Gerike, R. Analysis of visitor satisfaction with public transport in Munich. J. Public Transp. 2014, 17, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Olio, L.; Ibeas, A.; Cecín, P. Modelling user perception of bus transit quality. Transp. Policy. 2010, 17, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambas, M.E.L.; Giuffrida, N.; Ignaccolo, M.; Inturri, G. Comparison between bus rapid transit and light-rail transit systems: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach. WIT Trans. Built. Environ. 2018, 176, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, T. Managing Cruise Ship Impacts: Guidelines for Current and Potential Destination Communities. 2006. Available online: https://www.tourisk.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Managing-Cruise-Ship-Impacts.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Rubin, J. TEA/AECOM 2018 Theme Index and Museum Index: Global Attractions Attendance Report. Available online: http://www.teaconnect.org/pdf/TEAAECOM2013.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Raknes, G.; Hunskaar, S. Method paper-Distance and travel time to casualty clinics in Norway based on crowdsourced postcode coordinates: A comparison with other methods. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Coutinho-Rodrigues, J.; Antunes, C.H. A web spatial decision support system for vehicle routing using Google Maps. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dios Ortúzar, J.; Willumsen, L.G. Modelling Transport. 2011. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781119993308.fmatter (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Cheng, Y.H. Evaluating web site service quality in public transport: Evidence from Taiwan High Speed Rail. Transp. Res. Part C-Emerg. Technol. 2011, 19, 957–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, J.; Notteboom, T. The geography of cruises: Itineraries, not destinations. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 38, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLIA. The Contribution of the International Cruise Industry to the Global Economy in 2018. Available online: https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/global-cruise-impact-analysis---2019--final.ashx (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Geerts, W. Top 100 City Destinations 2018. Available online: http://go.euromonitor.com/rs/805-KOK-719/images/wpTop100CitiesEN_Final.pdf?mkt_tok=eyJpIjoiTURFeE56TTBOV1JrTW1GaSIsInQiOiJ0Tk5ibkJYZ3JFd2t5eWh1Qll6YjJMNjVabFdnWlRhbTRVZ1I5czNwNnhDRm02dFlEcjV3T1krMDc3bjN5YXpkUnJ3QnNpSm9xUkV0aHpnWkdJUWpobWUzS0Y5ZXJhcHQ4ZTBG (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Lam, W.H.K.; Bell, M.G.H. (Eds.) Advanced Modeling for Transit Operations and Service Planning; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2003; pp. 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhans, A.; Shahid, S.; Hassan, S.A. Assessment of bus service-quality using passengers’ perceptions. J. Teknol. 2015, 73, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.E.; Calver, S.; Watters, K.; Wilkes, K. Journeys to heritage attractions in the UK: A case study of National Trust property visitors in the south west. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Urban transport transitions: Copenhagen, city of cyclists. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 33, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Jiménez, C.; Perea-Medina, B.; Andrade, M.J.; Nebot, N. An examination of the territorial imbalance of the cruising activity in the main Mediterranean port destinations: Effects on sustainable transport. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 68, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovese, V. Venezia e il Turismo Insostenibile, SBS Your Language, 2019. Available online: https://www.sbs.com.au/language/italian/venezia-e-il-turismoinsostenibile (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Virtudes, A.; Debicka, A.; Janik, L.; Barwinska, M.; Choinacka, N.; Carrico, A. Soft Mobility as an Urban Design Solution for Water Fronts. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 221, 012154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbact. Tourism Friendly Cities, 2022. Available online: https://urbact.eu/networks/tourism-friendly-cities (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Schreurs, G.; Scheerlinck, K.; Gheysen, M. The local socio-economic impact of improved waterborne public transportation. The case of the New York City ferry service. J. Urban Mobil. 2022, 3, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-J.; Kim, Y.; Jang, S.; Kim, D.-K. Tourists’ preference on the combination of travel modes under Mobility-as-a-Service environment. Transp. Res. Part A-Policy Pract. 2021, 150, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hayashi, Y.; Frank, L.D. COVID-19 and transport: Findings from a world-wide expert survey. Transp. Policy. 2021, 103, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Urban Fabric | Symbol | Subarea | Symbol | Distance (Km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking + Transit + Car | WUF | Historic center | HC | 0–0.5 |

| Walking | Core | CW | 0–1 | |

| Edge | EW | 1–2 | ||

| Transit | TUF | Inner | IT | 2–8 |

| Outer | OT | 8–20 | ||

| Car | CUF | - | - | >20 |

| Indicator | Factor | Formula | V | Description | Value | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information [11,36] | Fi—Information & payment factor | Fi = (NL + NP + NC) /7 | NL | Number of languages that the webpage is available (maximum 4) | 1–4 | Appendix C |

| NP | There is no specific website for tourist passengers [48] | 0 | ||||

| There is a specific website for tourist passengers [48] | 1 | |||||

| Cost and payment method [38,39,40] | NC | No available intermodal transport ticket | 0 | |||

| Available intermodal transport ticket | 1 | |||||

| Available intermodal transport ticket and access museum card | 2 | |||||

| Time [37,38] | Fv—Velocity factor | Fv = D/5T | D | Total distance (km) | - | Google Maps |

| T | Total time (h) | - | ||||

| Availability [40] | Ff—Frequency factor | Ff = 5/F | F | Time (in minutes) between two stops of the same means of transport at the same place and the same direction | - | |

| Environmental impact | Fe—Environmental impact factor | Bus/ferry [42] | 0.5 | Appendix C | ||

| Tram/subway [41] | 1 | |||||

| Train [41] | 1 |

| Cruise Routes | City | Country | P | PM | Type | T | Tc | Tc/T (%) | M20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia & China | Hong Kong | China | 7.5 | 7.5 | Large | 29.8 | 700,000 | 2.3 | - |

| Northern Europe | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 0.7 | 2.0 | Medium | 8.5 | 425,000 | 5.0 | 2 |

| Central & Western Mediterranean | Venice | Italy | 0.3 | 0.9 | Small | 5.4 | 1,580,000 | 29.3 | - |

| Central & Western Mediterranean | Lisbon | Portugal | 0.6 | 2.9 | Medium | 3.8 | 515,514 | 13.6 | - |

| Canada/New England | Vancouver | Canada | 0.6 | 2.6 | Medium | 3.2 | 889,000 | 27.8 | - |

| Northern Europe | Copenhagen | Denmark | 0.6 | 1.7 | Medium | 3.0 | 865,000 | 28.8 | - |

| Western coast of North-America/Mexico/ California/Pacific Coast | San Francisco | USA | 0.8 | 7.2 | Large | 3.0 | 300,000 | 10.0 | 1 |

| Baltics | Stockholm | Sweden | 0.8 | 1.8 | Medium | 2.6 | 623,000 | 20.7 | - |

| Canada/New England | Quebec | Canada | 0.5 | 0.8 | Small | 2.9 | 200,000 | 6.9 | - |

| Central & Western Mediterranean | Malaga | Spain | 0.6 | 0.9 | Small | 2.3 | 505,633 | 22.0 | - |

| City (Origin Point) | Museum/CT | Subarea | V (2017) | R | Means of Transport | NL | Nc | NP | Fi | D (km) | T (h) | AV (km/h) | Fv | Ff | Fe | Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venice (St. Mark’s) | Cruise Terminal Venice (CT) | - | - | - | Ferry | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 2.9 | 0.57 | 5.80 | 1.02 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.05 |

| Palazzo Ducale | HC | 1,405,440 | 1 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.3 | 0.07 | 4.50 | - | - | - | - | |

| Peggy Guggenheim Collection | CW | 427,209 | 2 | Ferry | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 1.0 | 0.20 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.5 | 0.12 | |

| Correr Museum | HC | 334,820 | 3 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | 0.04 | 3.90 | - | - | - | - | |

| Galleria dell’Academia | EW | 316,995 | 4 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.1 | 0.23 | 4.72 | - | - | - | - | |

| Ca’Rezzonico | EW | 101,640 | 5 | Ferry | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7/7 | 1.2 | 0.20 | 6.00 | 1.20 | 0.08 | 0.5 | 0.05 | |

| Malaga (Constitution Square) | Cruise Terminal B (CT) | - | - | - | Walking | - | - | - | - | 2.5 | 0.51 | 4.84 | - | - | - | - |

| Picasso Museum | HC | 635,891 | 1 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.4 | 0.08 | 4.80 | - | - | - | - | |

| CAC | EW | 505,022 | 2 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.1 | 0.22 | 5.08 | - | - | - | - | |

| Pompidou Museum | EW | 168,143 | 3 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.1 | 0.23 | 4.71 | - | - | - | - | |

| Thyssen Museum | HC | 157,948 | 4 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | 0.03 | 3.00 | - | - | - | - | |

| Russian Museum | IT | 116,897 | 5 | Bus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2/7 | 3.1 | 0.58 | 5.31 | 1.02 | 0.40 | 0.5 | 0.06 | |

| Quebec (City Hall) | Quay Terminal 30 (CT) | - | - | - | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.2 | 0.25 | 4.80 | - | - | - | - |

| Museum of Civilization | CW | 559,179 | 1 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.8 | 0.17 | 4.80 | - | - | - | - | |

| National Museum of Arts | IT | 444,047 | 2 | Bus | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4/7 | 2.1 | 0.22 | 9.69 | 1.94 | 0.35 | 0.5 | 0.19 | |

| La Place-Royale Museum | CW | 84,708 | 3 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.6 | 0.12 | 5.14 | - | - | - | - | |

| L’Amérique Francophone Museum | HC | 60,221 | 4 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | 0.03 | 3.00 | - | - | - | - | |

| Maison Historique Chevalier | CW | 27,052 | 5 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.6 | 0.13 | 4.50 | - | - | - | - | |

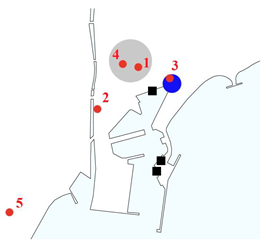

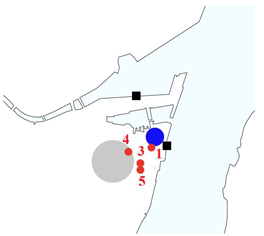

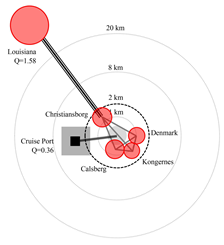

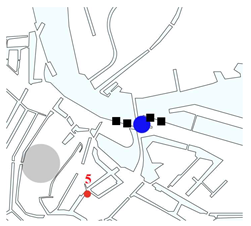

| Copenhagen (Rådhuspladsen) | Quay Terminal 3 (CT) | - | - | - | Tram/Subway | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4/7 | 7.8 | 0.62 | 12.65 | 2.53 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.36 |

| Louisiana Museum for Moderne Kunst | CUF | 657,293 | 1 | Train | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5/7 | 36 | 0.82 | 44.08 | 8.82 | 0.25 | 1 | 1.58 | |

| Christiansborg Slot | EW | 431,536 | 2 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.5 | 0.30 | 5.00 | - | - | - | - | |

| Ny Calsberg Glyptotek | CW | 410,160 | 3 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.8 | 0.15 | 5.33 | - | - | - | - | |

| National Museum of Denmark | CW | 351,373 | 4 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.0 | 0.20 | 5.00 | - | - | - | - | |

| Kongernes Samling | EW | 534,361 | 5 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.3 | 0.27 | 4.88 | - | - | - | - | |

| Stockholm (Stortoget) | Stockholm Cruise Center (CT) | - | - | - | Bus | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 4.5 | 0.40 | 11.25 | 2.25 | 0.42 | 0.5 | 0.27 |

| Vasamuseet | IT | 1,496,000 | 1 | Bus | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 2.5 | 0.28 | 8.83 | 1.76 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.17 | |

| Skansen Museum | IT | 1,342,763 | 2 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 2.7 | 0.42 | 6.48 | 1.30 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.37 | |

| Naturhistoriska | IT | 648,000 | 3 | Bus | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 5.4 | 0.38 | 14.09 | 2.82 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.80 | |

| ArkDes | EW | 581,383 | 4 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.7 | 0.33 | 5.10 | - | - | - | - | |

| Moderna museet | EW | 581,383 | 5 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 1.5 | 0.30 | 5.00 | - | - | - | - | |

| Amsterdam (Dam Square) | Cruise Ship Passenger (CT) | - | - | - | Tram/Subway | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5/7 | 2.4 | 0.27 | 9.00 | 1.80 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.64 |

| Van Gogh Museum (*) | IT | 2,260,000 | 1 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5/7 | 2.2 | 0.23 | 9.44 | 1.89 | 1.25 | 1 | 1.68 | |

| Rijksmuseum (*) | EW | 2,160,000 | 2 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5/7 | 1.7 | 0.18 | 9.29 | 1.85 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.66 | |

| Anna Frank House | CW | 1,266,966 | 3 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5/7 | 0.8 | 0.13 | 6.02 | 1.20 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.61 | |

| Stedelijk Museum | IT | 691,851 | 4 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5/7 | 2.3 | 0.25 | 9.20 | 1.84 | 1.25 | 1 | 1.64 | |

| Rembrandt Museum | CW | 265,000 | 5 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.7 | 0.13 | 5.38 | - | - | - | - | |

| Vancouver (Robson) | Canada Place (CT) | - | - | - | Bus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2/7 | 0.9 | 0.15 | 6.00 | 1.20 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.03 |

| Science World | IT | 749,790 | 1 | Bus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2/7 | 2.2 | 0.33 | 6,61 | 1.32 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.08 | |

| Vancouver Art Gallery | HC | 601,242 | 2 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.0 | 0.02 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | |

| Museum of Anthropology | OT | 200,559 | 3 | Bus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2/7 | 18.5 | 0.75 | 24.68 | 4.94 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.12 | |

| HR MacMillan Space Center | IT | 125,587 | 4 | Bus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2/7 | 2.7 | 0.35 | 7.71 | 1.54 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.04 | |

| Vancouver Maritime Museum | IT | 65,058 | 5 | Bus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2/7 | 2.9 | 0.35 | 8.29 | 1.66 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.04 | |

| San Francisco (Union Square) | James R. Herman (CT) | - | - | - | Bus | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6/7 | 2.7 | 0.62 | 7.83 | 0.89 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.10 |

| California Academy of Science (*) | IT | 1,160,000 | 1 | Bus | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6/7 | 6.1 | 0.47 | 13.13 | 2.62 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.19 | |

| San Francisco Museum Modern Art | CW | 1,113,984 | 2 | Walking | - | - | - | - | 0.8 | 0.17 | 4.80 | - | - | - | - | |

| De Young | IT | 994,000 | 3 | Bus | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6/7 | 6.3 | 0.67 | 9.41 | 1.88 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.13 | |

| Exploratorium | IT | 849,702 | 4 | Bus | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6/7 | 2.4 | 0.32 | 7.61 | 1.52 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.16 | |

| Legion of Honor | OT | 475,000 | 5 | Bus | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6/7 | 8.6 | 0.68 | 12.64 | 2.54 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.18 | |

| Lisbon (Marquet) | Lisbon Cruise Port Jardim (CT) | - | - | - | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3/7 | 1.2 | 0.18 | 6.55 | 1.31 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.23 |

| Berardo Collection Museum | IT | 1,006,145 | 1 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3/7 | 6.7 | 0.50 | 13.40 | 2.68 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.48 | |

| National Museum of Cars | IT | 350,254 | 2 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3/7 | 5.7 | 0.43 | 13.68 | 2.63 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.47 | |

| National Museum of Ancient Art | IT | 212,669 | 3 | Bus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3/7 | 2.4 | 0.23 | 10.28 | 2.06 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.15 | |

| National Museum of Tiles | IT | 193,444 | 4 | Bus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3/7 | 2.9 | 0.25 | 11.60 | 2.32 | 0.83 | 0.5 | 0.41 | |

| National Museum of Archaeology | IT | 167,634 | 5 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3/7 | 6.6 | 0.50 | 14.67 | 2.64 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.47 | |

| Hong Kong (Statue Square) | Ocean Terminal (CT) | - | - | - | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 2.2 | 0.27 | 4.89 | 1.65 | 2.50 | 1 | 2.36 |

| Hong Kong Science Museum | IT | 2,016,553 | 1 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 3.2 | 0.33 | 9.60 | 1.92 | 1.25 | 1 | 1.37 | |

| Museum of History | IT | 1,491,899 | 2 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 3.2 | 0.30 | 9.60 | 2.13 | 1.25 | 1 | 1.52 | |

| Hong Kong Heritage Museum | OT | 1,142,235 | 3 | Bus | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5/7 | 15 | 0.67 | 22.50 | 4.50 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.54 | |

| Hong Kong Space Museum | IT | 432,394 | 4 | Tram/Subway | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/7 | 2.2 | 0.28 | 7.33 | 1.55 | 1.25 | 1 | 1.11 | |

| Hong Kong Railway Museum | CUF | 295,479 | 5 | Bus | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5/7 | 25 | 0.88 | 30.00 | 5.66 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.67 |

| R | City | Level—Main PT (Qmin − Qmax)/Q (CT) |

|---|---|---|

| Venice | Level 1—Ferry (0.05–0.12)/0.05 | |

| 1. Doge’s Palace (HC) 2. Peggy Guggenheim Collection (CW) 3. Correr Museum (HC) 4. Academia (EW) 5. Ca’Rezzonico (EW) |  |  |

| Malaga | Level 2—Bus (0.06)/- | |

| 1. Picasso (HC) 2. CAC (EW) 3. Pompidou (EW) 4. Thyssen (CH) 5. Russian (IT) |  |  |

| Quebec | Level 2—Bus (0.19)/- | |

| 1. Civilization (CW) 2. Arts (IT) 3. La Place Royale (CW) 4. L’Amérique Francophone (HC) 5. Maison Historique Chevalier (CW) |  |  |

| Copenhagen | Level 2—Train (1.58)/0.38 | |

| 1. Lousiana (CUF) 2. Christiansborg Slot (EW) 3. Ny Calsberg Glyptotek (CW) 4. Denmark (CW) 5. Kongernes Samling (EW) |  |  |

| ||

| R | City | Level—Main PT (Qmin − Qmax)/Q (CT) |

|---|---|---|

| Stockholm | Level 3—Bus/sub (0.17–0.80)/0.27 | |

| 1. Vasamuseet (IT) 2. Skansen (IT) 3. Naturhistoriska (IT) 4. ArkDes (EW) 5. Moderna museet (EW) |  |  |

| Amsterdam | Level 3—Sub (0.61–1.68)/0.64 | |

| 1. Van Gogh (IT) 2. Rijksmuseum (EW) 3. Anna Frank House (CW) 4. Stedelijk (IT) 5. Rembrandt (CW) |  |  |

| Vancouver | Level 4—Bus (0.04–0.12)/0.03 | |

| 1. Science World (IT) 2. Vancouver Art Gallery (HC) 3. Anthropology (OT) 4. HR MacMillan Space Center (IT) 5. Vancouver Maritime (IT) |  |  |

| San Francisco | Level 4—Bus (0.13–0.16)/0.10 | |

| 1. California Academy of Science (IT) 2. San Francisco Museum Modern Arts (CW) 3. De Young (IT) 4. Exploratorium (IT) 5. Legion of Honor (OT) |  |  |

| ||

| R | City | Level—Main PT (Qmin − Qmax)/Q (CT) |

|---|---|---|

| Lisbon | Bus/Tram (0.15–0.48)/0.23 | |

| 1. Berardo Collection (IT) 2. National Museum of Cars (IT) 3. National Museum of Ancient Art (IT) 4. National Museum of Tiles (IT) 5. National Museum of Archaeology (IT) |  |  |

| Hong Kong | Bus/ Sub (0.54–1.52)/2.36 | |

| 1. Hong Kong Science (IT) 2. History (IT) 3. Hong Kong Heritage (OT) 4. Hong Kong Space (IT) 5. Hong Kong Railway (CUF) |  |  |

| ||

| Destination | Size | CL | PT (Q min—Q max) | TC/P | DCT (km) | PWUF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venice | Small | N1 | Ferry (0.10–0.24) | A | 2.9 | 68.60 |

| Malaga | Small | N2 | Bus (0.06) | B | 2.5 | 63.78 |

| Quebec | Small | N2 | Bus (0.19) / - | B | 1.2 | 25.21 |

| Copenhagen | Medium | N2 | Train (1.58) | B | 7.8 | 52.52 |

| Stockholm | Medium | N3 | Bus/sub (0.17–0.80) | C | 0.9 | 55.77 |

| Amsterdam | Medium | N3 | Sub (0.61–1.68) | C | 2.4 | 43.10 |

| San Francisco | Large | N4 | Bus (0.13–0.16) | C | 2.7 | 37.13 |

| Vancouver | Medium | N4 | Bus (0.04–0.12) | B | 0.9 | 18.75 |

| Lisbon | Medium | N5 | Bus/Tram (0.15–0.48) | C | 1.2 | - |

| Hong Kong | Large | N5 | Bus/Sub (0.54–1.52) | C | 2.2 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosa-Jiménez, C.; Gutiérrez-Coronil, S.; Márquez-Ballesteros, M.J.; García-Moreno, A.E. Relating Spatial Quality of Public Transportation and the Most Visited Museums: Revisiting Sustainable Mobility of Waterfronts and Historic Centers in International Cruise Destinations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032066

Rosa-Jiménez C, Gutiérrez-Coronil S, Márquez-Ballesteros MJ, García-Moreno AE. Relating Spatial Quality of Public Transportation and the Most Visited Museums: Revisiting Sustainable Mobility of Waterfronts and Historic Centers in International Cruise Destinations. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032066

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosa-Jiménez, Carlos, Sergio Gutiérrez-Coronil, María José Márquez-Ballesteros, and Alberto E. García-Moreno. 2023. "Relating Spatial Quality of Public Transportation and the Most Visited Museums: Revisiting Sustainable Mobility of Waterfronts and Historic Centers in International Cruise Destinations" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032066

APA StyleRosa-Jiménez, C., Gutiérrez-Coronil, S., Márquez-Ballesteros, M. J., & García-Moreno, A. E. (2023). Relating Spatial Quality of Public Transportation and the Most Visited Museums: Revisiting Sustainable Mobility of Waterfronts and Historic Centers in International Cruise Destinations. Sustainability, 15(3), 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032066

_Li.png)