A Novel Offsite Construction Method for Social Housing in Emerging Economies for Low Cost and Reduced Environmental Impact

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Developing Countries and Emerging Economies

1.2. Offsite Construction

1.3. Transport and Lifting

1.4. 3D Volumetric Modules

- There are accessibility barriers to building social housing in developing countries, such as roads that have high slopes and are too narrow for large trucks.

- Most modular constructions are structurally oversized to resist mechanical efforts due to transport and lifting.

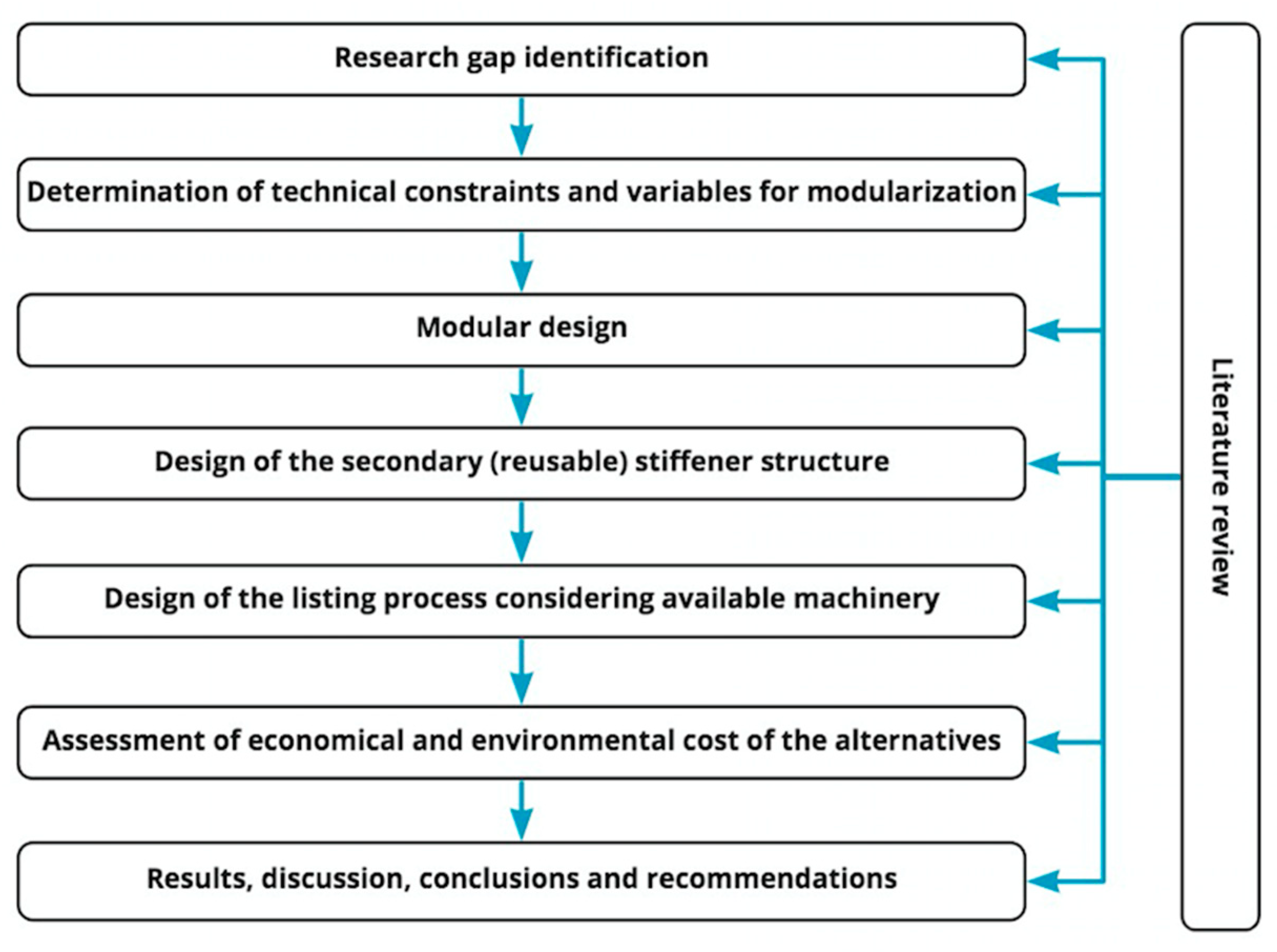

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

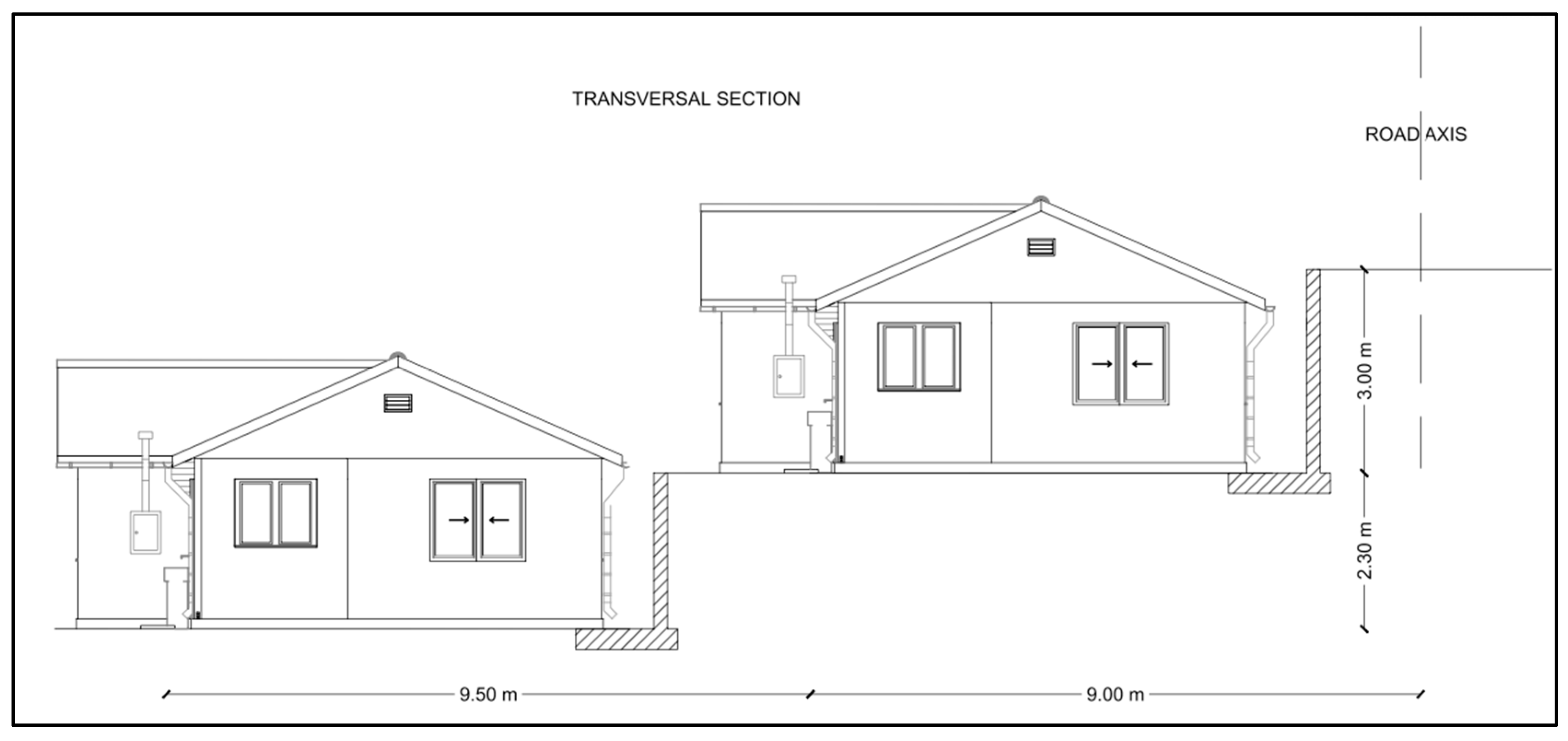

3.1. Determination of Technical Constraints for Modularisation

3.1.1. Current Regulations for the Construction of Social Housing

3.1.2. Transportation Regulation

| 2.60 [m] |

| 4.20 [m] |

| 20.50 [m] |

3.1.3. Interferences Caused by Public Electricity and Telecommunications Networks

| 4.6 [m] |

| 5.0 [m] |

| Not established |

3.1.4. Morphology of the Construction Site

- Slopes: The literature indicates that cranes can only work on horizontal surfaces. In cases with gentle slopes or that are not wholly uniform, support platforms for stabilisers are used. Even so, it is pointed out that the maximum slope of the access road cannot be greater than 5% [75].

- Street width: The cases analysed have 6 m wide streets, so the possibility of extending the stabilisers of lifting equipment to 100% must be verified in each project.

- Elevation between the access road and construction platform plus maximum horizontal lift distance: These aspects will be analysed based on the maximum load tables provided by the equipment manufacturers.

3.2. Modular Design

- Finishes like coating mud, joint angles, paint, and tiles are not considered in the calculation.

- The duplication of the supporting structure that occurs due to adjacent walls between different volumes is not considered.

- The weight of screws and minor fixings between construction elements is not considered.

- Only the weight from the finished floor level upwards is considered because the floor structure is made of in situ concrete.

- For better performance during the transport and lifting process, the weights of the modules assume they were structured without door and window openings.

- Additional reinforcements to the supporting structure for lifting are not considered.

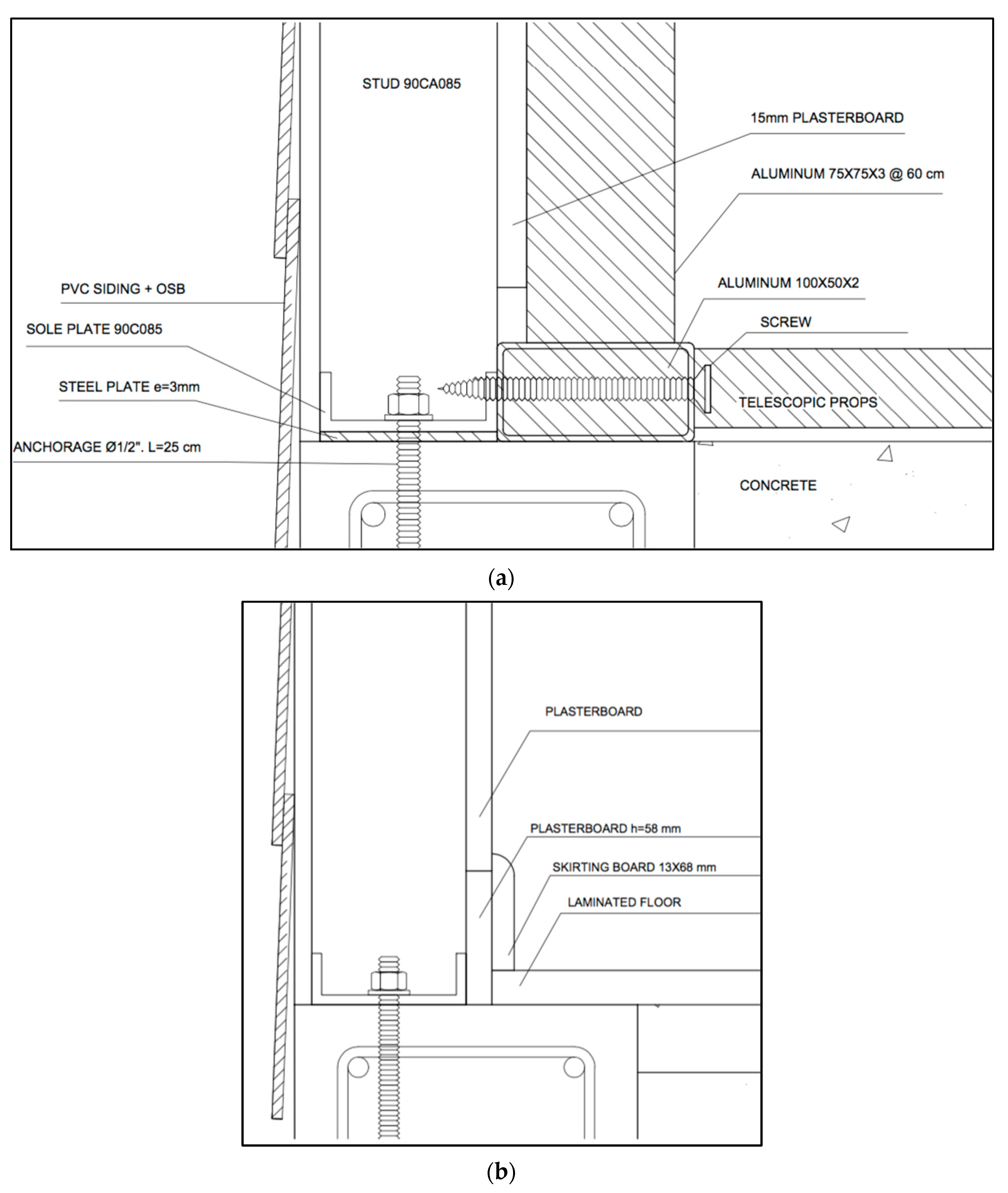

3.3. Design of the External Temporary and Auxiliary Stiffener Structure (ETASS)

- Direct pick points: The crane hook is connected employing slings or cables directly to “pick points” incorporated in the structure, which produces internal forces throughout the structure [57].

- Wrap-around slings: These support the module from below in two continuous strips, so rigidity is required in the lower part of the structure to avoid damage produced by internal forces and drifts.

- Spreader bars: These are used to provide lifting forces to act vertically on the structure [57], and they can be implemented considering complex arrangements to have several “pick points.” They produce lower internal forces than the direct pick point method, but they also require structural reinforcements.

- Trays: These are used for more minor elements, generally called “pods,” and are accompanied by specialised secondary equipment that allows the pods to be moved to their final location [77], which makes reinforcements in the lower part essential.

- Each module should be installed adjacent to another by at least one of its exterior faces. Because of that, the rigging accessories should not be located outside the structure in order to avoid damage to the exterior faces of the other modules.

- In order to avoid oversizing the original structure of the module, the use of hooks tied to the module itself should be discarded.

- The module does not have a floor structure because the house must have a concrete floor built onsite.

- The ETASS must be reusable for various architectures and module sizes in order to provide a solution for developing countries with diseconomies of scale in housing construction.

- The maximum permitted displacements related to the height (h) of the element, according to the regulations in Chile, are 2/1000 × h [78], that is, 4.8 mm. The deformations specified in the regulation are to prevent the collapse of the structure, but not to prevent damage to the finishes, so a maximum deformation criterion of 0.5 mm will be used because it has been determined that 10 mm thick plasterboard panels begin to suffer damage around this value [62]. This is a conservative assumption considering the 15 mm thickness of the actual case modules proposed in this study.

- An amplification factor of 4.3 is adopted to multiply self-weight in positive and negative directions in two different load combinations, based on the perpendicular acceleration of 32 m/s2 obtained for speeds of 5.6 km/h obtained based on experimental data [79].

- A maximum slope of 12% is considered following the urban road geometric design provisions of current regulations [81].

- A 178 kgf load applied to the pick points is considered, which corresponds to the horizontal component produced at these points, the product of the module’s dead loads.

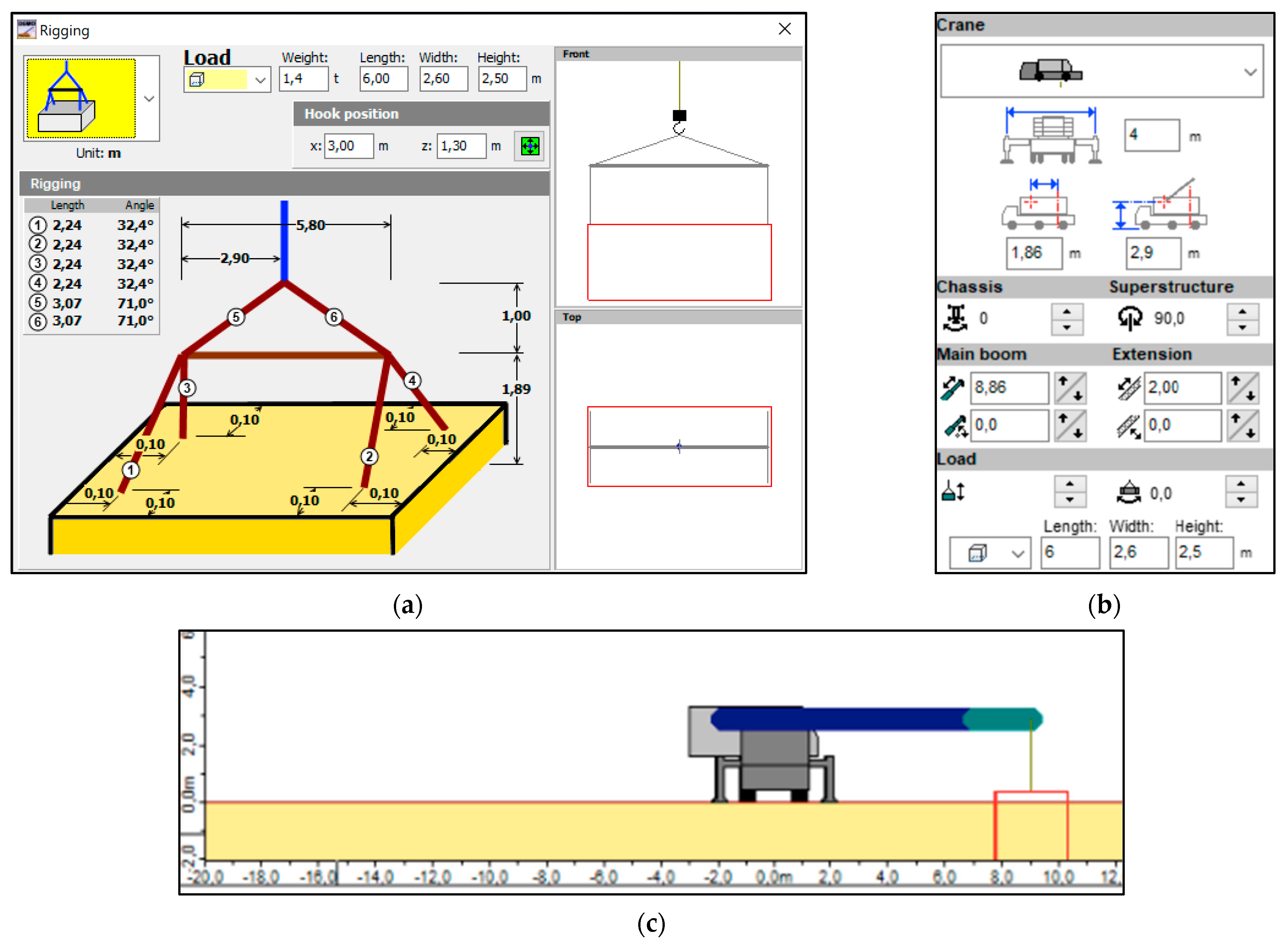

3.4. Design of the Lifting Process Considering Available Machinery

- Derricks: This equipment requires a large surface to install the guy-wires needed to provide stability to the machinery. Also, some of the parts usually need mechanical assistance (crane trucks or winches) to be mounted in the operational position.

- Forklifts: This equipment is usually used in volumetric modules’ installation, but a flat transit surface is always needed. This last aspect is unusual in the projects in the scope of this research.

- Tower Cranes: This type of equipment requires less space on the construction platform, making it possible to avoid interferences. A specially designed, dismountable tower crane should be a feasible alternative.

4. Discussion

Assessment of Economic and Environmental Cost of the Alternatives

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The traditional modularisation method increases the cost of social housing because the structure must be oversized. Then, the increased cost is an obstacle to the possibility of financing the modularisation of social housing in developing countries and EEs.

- The novel offsite construction method allows the prefabrication of social housing with less direct cost compared to the traditional methodology. Consequently, savings are produced by avoiding the cold-formed steel structure of the traditional offsite construction methodologies for modules.

- The novel offsite construction method allows the prefabrication of social housing with less environmental impact compared with the traditional methodology. It is important to highlight that the technical evaluation of both cost and environmental impact was performed according to Chilean regulations for this type of infrastructure.

- Since offsite construction methods are in their early stages in Chile, the market for machinery and other related equipment needs to be adapted to this new type of methodology in order to allow the optimisation of cost and productivity enhancements to construction processes.

- Since this paper is mostly focused on practitioners and scientists, policy makers are outside the scope of this research. However, we are certain that the results of this paper can be considered in public policies on social housing to encourage more affordable and environmentally friendly industrialised housing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Déficit Habitacional en América Latina y el Caribe; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Samarasinghe, D.A.S. The housing crisis in Australia and New Zealand: A comparative analysis through policy lenses. Int. J. Constr. Supply Chain. Manag. 2020, 10, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpezzi, S. Housing affordability and responses during times of stress: A preliminary look during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2023, 41, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangura, M.; Lee, C.L. The determinants of homeownership affordability in Greater Sydney: Evidence from a submarket analysis. Hous. Stud. 2023, 38, 206–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, U.; Hayo, B.; Erol, I. The Effect of Immigration on the German Housing Market. SSRN Electron. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. In Summary for Policymakers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Naciones Unidas. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible Una Oportunidad Para América Latina y el Caribe Gracias Por su Interés en Esta Publicación de la CEPAL. 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/40155/24/S1801141_es.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- OECD. Value Added by Activity. Total, Annual Growth Rate (%), 1990–2020. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/chart/6skv (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- IEA. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction Sector 2019; IEA: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Country Classifications; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Emerging Economies and the Monetary Tightening Path in the United States Development Issues No. 12; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Economic Situation and Prospects as of Mid-2020; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CChC. Fundamenta 45—Gerencia de Estudios CChC El Sector de la Construcción ante el Desafío Climático Global; CCHC: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Tracking Progress towards Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goodier, C.; Gibb, A. Future opportunities for offsite in the UK. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2007, 25, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.G. Why Construction Industry Productivity Is Declining. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1985, 67, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Mandal, S.N.; Thanikal, J.V.; Saurabh, K. Evolution of studies in construction productivity: A systematic literature review (2006–2017). Ain Shams Eng. J. 2019, 10, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company; M. G. Institute. Reinventing Construction: A Route To Higher Productivity; McKinsey & Company: Chicaco, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional de Productividad. Productividad en el Sector de la Construcción; Comisión Nacional de Productividad: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tatum, C.B.; Vanegas, J.A.; Williams, J.M. Constructability Improvement Using Prefabrication, Preassembly, and Modularization; Bureau of Engineering Research, University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Švajlenka, J.; Kozlovská, M.; Spišáková, M. The benefits of modern method of construction based on wood in the context of sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 14, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabihi, H.; Habib, F.; Mirsaeedie, L. Definitions, concepts and new directions in Industrialized Building Systems (IBS). KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2013, 17, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guerrero, R.E.; Vera, S.; Carpio, M. A quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the sustainability of industrialised building systems: A bibliographic review and analysis of case studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghchesaraei, O.R.; Lavasani, H.H.; Baghchesaraei, A. Behavior of Prefabricated Structures in Developed and Developing Countries. Bull. Société Sci. Liège 2016, 85, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. Un Espacio Para el Desarrollo: Los Mercados de Vivienda en América Latina y el Caribe; Estados Unidos: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmageed, S.; Zayed, T. A study of literature in modular integrated construction—Critical review and future directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lychgate Projects Ltd. Modern Methods of Construction: Views from the Industry. 2016. Available online: http://www.nhbcfoundation.org/Publications/Primary-Research/Modern-methods-of-construction-NF70 (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Brennan, J.; Vokes, C.; CITB. Faster, Smarter, More Efficient: Building Skills for Offsite Construction. April 2017. Available online: https://www.citb.co.uk/documents/research/offsite_construction/offsite_construction_full_report_20170410.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Azman, M.N.A.; Ahamad, M.S.S.; Husin, W.M.A.W. Comparative Study on Prefabrication Construction Process. Int. Surv. Res. J. 2012, 2, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, N.; Fuchs, S.; Mischke, J.; Palter, R.; Strube, G.; Woetzel, J. Modular Construction: From Projects to Products. June 2019. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/capital-projects-and-infrastructure/our-insights/modular-construction-from-projects-to-products (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Bendi, D.; Rana, M.Q.; Arif, M.; Goulding, J.S.; Sawhney, A. An off-site construction readiness maturity model for the Indian construction sector. Constr. Innov. 2020, 21, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnanunny, M.; Anoop, K. Prefab technology a solution to existing challenges in construction sector of India—A Kerala perspective. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2018, 119, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K.; Cheng, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z. Environmental Cost-Benefit Analysis of Prefabricated Public Housing in Beijing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-H.; Chan, E.H.-W.; Lok, L.K.-L. Prefabrication and barriers to entry—A case study of public housing and institutional buildings in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 482–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Skitmore, M.; Peng, Y. Exploring the challenges to industrialized residential building in China. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W. Barriers to promoting prefabricated construction in China: A cost–benefit analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, L. Identifying barriers to off-site construction using grey DEMATEL approach: Case of China. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2018, 24, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khahro, S.H.; Memon, N.A.; Ali, T.H.; Memon, Z.A. Adoption of Prefabrication in Small Scale Construction Projects. Civ. Eng. J. 2019, 5, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.-G.; Shan, M.; Looi, K.-Y. Key constraints and mitigation strategies for prefabricated prefinished volumetric construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, R.; Lim, J.B.; González, V.A. Performance of the supply chains for New Zealand prefabricated house-building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 64, 102537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhaty, Y.; Kaluarachchi, Y. Critical success factors, barriers and challenges for adopting offsite prefabrication: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the ARCOM 2020—Association of Researchers in Construction Management, 36th Annual Conference 2020—Proceedings, Online, 7–8 September 2020; pp. 366–375. [Google Scholar]

- Girma, S.; Chimdi, J.; Mosisa, A. Challenges of Using Prefabrication Technology in Oromia Regional State. J. Civ. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 22–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.; Mesa, H.A.; Alarcón, L.F. The interrelationship between barriers impeding the adoption of off-site construction in developing countries: The case of Chile. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q. Barriers to the adoption of modular integrated construction: Systematic review and meta-analysis, integrated conceptual framework, and strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinaitwe, H.M.; Mwakali, J.; Hansson, B. Assessing the degree of industrialisation in construction—A case of Uganda. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2006, 12, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Torres, A. El Contexto Económico, Social y Tecnológico de la Producción de Vivienda Social en América Latina; Encuentro Latinoamericano de Gestión y Economía de la Construcción: Bogotá, Colombia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kempton, J.; Fergusson, S. Potential of Prefabricated Pods to Extend Houses: Initial Feasibility Study for Social Housing. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual ARCOM Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 1–3 September 2004; Khosrowshahi, F., Ed.; Volume 1, pp. 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, A. Construcción Industrializada Para la Vivienda Social en Chile: Análisis De Su Impacto Potencial. Ciclo de Seminarios Académicos de Economía. 2010. p. 44. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/38703170/Paper-Vivienda-Industrializada-AAD-Oct2010-.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1537056744&Signature=RrOTK6u5wlz7UxEYTW1YUjLdQ3c%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3Bfilename%3DVivi (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Building and Construction Authority. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DFMA); Building and Construction Authority: Singapore, 2009.

- López, J.J.; López, C. El Urbanismo de ladera: Un reto ambiental, tecnológico y del ordenamiento territorial. Bitácora Urbano Territ. 2004, 1, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Velamati, S. Feasibility, Benefits and Challenges of Modular Construction in High Rise Development in the United States: A Developer’s Perspective; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’connor, J.T.; O’brien, W.J.; Choi, J.O. Industrial Project Execution Planning: Modularization versus Stick-Built. Pr. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2016, 21, 04015014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G.C.; Vicente, R.; Azenha, M.; Ferreira, T.M. A systematic review of Prefabricated Enclosure Wall Panel Systems: Focus on technology driven for performance requirements. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana-Moral, F.J.; Jiménez, A.J.S.; Such, A.V.; Padura, Á.B.; Huelva, M.M. Análisis de ciclo de vida y prefabricación. Evaluación del desempeño ambiental de diferentes sistemas industrializados en la edificación. In II Congreso Internacional y IV Nacional de Construcción Sostenible y Soluciones Eco-Eficientes; Depósito de Investigación Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2015; pp. 1020–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon, L.; Poon, C.S. Sustainable construction aspects of using prefabrication in dense urban environment: A Hong Kong case study. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2008, 26, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, T.; Salah, A.; Moselhi, O.; Al-Hussein, M. Near optimum selection of module configuration for efficient modular construction. Autom. Constr. 2017, 83, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E. Prefab Architecture: A Guide to Modular Design and Construction; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hobobken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, A.W.; Chen, W.; Hao, H.; Bi, K. Structural response of modular buildings—An overview. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innella, F.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, Z. Mechanical performance of building modules during road transportation. Eng. Struct. 2020, 223, 111185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiz, A.; Smith, I. Lifting and Transportation Forces in Prefabricated Units Field Test. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering, Portland, OR, USA, 6–10 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Valinejadshoubi, M.; Bagchi, A.; Moselhi, O. Damage detection for prefabricated building modules during transportation. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142, 04018031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innella, F.; Luo, F.J.; Bai, Y. Capacity of Screw Connections between Plasterboard Panels and Cold-Formed Steel for Modular Buildings. J. Archit. Eng. 2018, 24, 04018031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruen, J.; Hadjri, K.; von Meding, J. Design Drivers for Affordable and Sustainable Housing in Developing Countries. J. Civ. Eng. Arch. 2013, 7, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Ganiyu, B.; Fopohunda, J.; Haldenwng, R. Construction Approaches to Enhance Sustainability in Affordable Housing in Developing Countries. In Proceedings of the 2015 World Congress on Sustainable Technologies (WCST), London, UK, 14–16 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Servicio de Vivienda y Urbanización V Región. Licitación ID: 704093-153-LR20 LP 124-2020 CONSTRUCCIÓN VIVIENDAS LIMACHE. Available online: https://www.mercadopublico.cl/Procurement/Modules/RFB/DetailsAcquisition.aspx?qs=o7TQSQtm1T/1zWs8BJjyXw== (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- CSI. SAP2000 Integrated Software for Structural Analysis and Design; Computers and Structures Inc.: Berkley, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scholl, M. Kranxpert Demo Version; Informer Technologies: Altenkunstadt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. Programa Habitacional Fondo Solidario de Elección de Vivienda; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo: Santiago, Chile, 2011.

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. Itemizado Tecnico de Construccion Para Proyectos del Fondo Solidario de Eleccion de Vivienda; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo: Santiago, Chile, 2012.

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. Cuadro Normativo y Tabla de Espacios y Usos Minimos Para el Mobiliario; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo: Santiago, Chile, 2017.

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. Ordenanza General de Urbanismo y Construcciones; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo: Santiago, Chile, 2017.

- Ministerio de Transportes y Telecomunicaciones. Resolucion No 1 de 1995 del Ministerio de Transportes y Telecomunicaciones. In Establece Dimensiones Maximas a Vehiculos; Ministerio de Transportes y Telecomunicaciones: Santiago, Chile, 1995; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- NSEG 5. E.n.71; Reglamento de Instalaciones Electricas de Corrientes Fuertes. Superintendencia de Electricidad y Combustibles: Santiago, Chile, 1971.

- Subsecretaria de Telecomunicaciones. Cableado. Available online: https://www.subtel.gob.cl/cableado/ (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- National Modular Housing Council. Builder’s Guide to Modular Home Set-Up & Completion. Available online: https://www.manufacturedhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Builders-Guide-to-Modular-Home-Set-Up-Completion.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Corporacion de Desarrollo Tecnológico. La Plataforma Online de Apoyo a la Especificacion Tecnica. Available online: http://www.especificar.cl/ (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- The Modular Building Institute. Bathroom Pods; The Modular Building Institute: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Normalizacion. Diseño Sísmico de Edificios; Instituto Nacional de Normalizacion: Santiago, Chile, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Godbole, S.; Lam, N.; Mafas, M.; Fernando, S.; Gad, E.; Hashemi, J. Dynamic loading on a prefabricated modular unit of a building during road transportation. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 18, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Nacional de Normalizacion. Diseño Estructural—Cargas De Viento; Instituto de Nacional de Normalizacion: Santiago, Chile, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. Manual de Obras de Vialidad, Pavimentación y Aguas Lluvias; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo: Santiago, Chile, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 1–46.

- EN 15978: 2011; BS EN 15978:2011—Sustainability of Construction Works—Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings—Calculation Method. iTeh Standards: Newark, DE, USA, 2011.

- EN 15978: 2011; BRE Global Methodology for the Environmental Assessment of Buildings Using. BRE Global: London, UK, 2018.

- Lin, Y.; Yang, H.; Ma, L.; Li, Z.; Ni, W. Low-Carbon Development for the Iron and Steel Industry in China and the World: Status Quo, Future Vision, and Key Actions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Hasanbeigi, A.; Zhang, W.; Lu, H.; Arens, M. Comprehensive assessment of energy conservation and CO2 emissions mitigation in China’s iron and steel industry based on dynamic material flows. Appl. Energy 2018, 209, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Steel Association. Steel Statistical Yearbook 2020 Extended Version; World Steel Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Weight Calculation—Module M-1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Description | Unitary Weight | Unit | Qty. | Longitude | Total Weight [kg] |

| Studs | C 2 × 3 × 0.85 | 0.8 | mL | 14.0 | 2.4 | 26.9 |

| Sole plate | U 2 × 3 × 0.85 | 0.7 | mL | 9.0 | 2.4 | 15.1 |

| Top plate | U 2 × 3 × 0.85 | 0.7 | mL | 9.0 | 2.4 | 15.1 |

| Interior finishes | Plasterboard 15 mm | 12.0 | m2 | 21.7 | 260.4 | |

| Condensation barrier | 0.1 | m2 | 21.7 | 2.2 | ||

| Exterior finishes | Asphalt paper 10/40 | 0.2 | m2 | 10.8 | 2.2 | |

| OSB 9.5 mm | 7.1 | m2 | 10.8 | 76.7 | ||

| PVC Siding | 1.6 | m2 | 10.8 | 17.3 | ||

| Electricity | Conduit plug 1/2″ | 0.2 | mL | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.6 |

| Conduit lighting 1/2″ | 0.2 | mL | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | |

| Conduit switch 1/2″ | 0.2 | mL | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.4 | |

| Wires 1.5 mm | 0.12 | mL | 3.0 | 10.0 | 3.6 | |

| Door | Door | 11.8 | uni | 1.0 | 11.8 | |

| Screws | Screws (all types used in Drywall system) | 7.5 | gL | 1.0 | 7.5 | |

| Window | Widow 100 × 100 × 3 mm | 8.4 | uni | 1.0 | 8.4 | |

| Total weight [kg] | 449.2 | |||||

| Combinations | Load Multipliers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combo | Dead (Self-Weight) | Dead (Module Weight) | W (Wind) | S (Slings) | |

| Case 1: Transport | Combo 1 | 1 (Gravity direction) | 1 (Gravity direction) | 1 (X direction) | 0 |

| Combo 2 | −4.3 (Gravity direction) | −4.3 (Gravity direction) | 1 (X direction) | 0 | |

| Combo 3 | 4.3 (Gravity direction) | 4.3 (Gravity direction) | 1 (X direction) | 0 | |

| Combo 4 | 1 (12% deviation) | 1 (12% deviation) | 1 (X direction) | 0 | |

| Case 2: Lifting | Combo 5 | 1 (Gravity direction) | 1 (Gravity direction) | 0 | 1 (X and −X) |

| Joint Displacements | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASE | Joint | OutputCase | CaseType | U1 | U2 | U3 | R1 | R2 | R3 |

| Text | Text | Text | Text | m | m | m | Radians | Radians | Radians |

| 1 | 78 | Combo 1 | Combination | −3.899 × 10−6 | −6.342 × 10−6 | −0.000151 | −0.000116 | −0.000078 | −0.000047 |

| 1 | 70 | Combo 1 | Combination | −3.204 × 10−6 | 0.000012 | −0.000142 | 0.000124 | 0.000189 | 0.000031 |

| 1 | 74 | Combo 1 | Combination | −0.000138 | 3.734 × 10−6 | −0.000298 | 6.904 × 10−6 | 0.002846 | −0.000013 |

| 1 | 55 | Combo 1 | Combination | 0.000076 | −3.459 × 10−6 | 0.000127 | −0.000029 | 0.002372 | −0.000012 |

| 1 | 78 | Combo 2 | LinStatic | 0.000061 | −9.285 × 10−6 | −0.000138 | −0.000125 | −0.002279 | −0.000062 |

| 1 | 70 | Combo 2 | LinStatic | 0.000041 | 0.000015 | −0.000128 | 0.000138 | −0.002013 | 0.000024 |

| 1 | 73 | Combo 2 | LinStatic | 0.000221 | −2.89 × 10−6 | −0.000429 | 2.047 × 10−6 | 0.003117 | 1.328 × 10−6 |

| 1 | 51 | Combo 2 | LinStatic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000013 | 0.001809 | 5.663 × 10−6 |

| 1 | 78 | Combo 3 | LinStatic | 0.000061 | −9.285 × 10−6 | −0.000138 | −0.000125 | −0.002279 | −0.000062 |

| 1 | 70 | Combo 3 | LinStatic | 0.000041 | 0.000015 | −0.000128 | 0.000138 | −0.002013 | 0.000024 |

| 1 | 73 | Combo 3 | LinStatic | 0.000221 | −2.89 × 10−6 | −0.000429 | 2.047 × 10−6 | 0.003117 | 1.328 × 10−6 |

| 1 | 51 | Combo 3 | LinStatic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000013 | 0.001809 | 5.663 × 10−6 |

| 1 | 78 | Combo 4 | LinStatic | 0.000061 | −0.000014 | −0.000125 | −0.000136 | −0.001905 | −0.000028 |

| 1 | 70 | COMBO 4 | LinStatic | 0.00004 | 0.000014 | −0.000128 | 0.000136 | −0.002013 | 0.000024 |

| 1 | 73 | COMBO 4 | LinStatic | 0.000213 | −3.115 × 10−8 | −0.000421 | −3.173 × 10−7 | 0.003081 | −8.588 × 10−7 |

| 1 | 51 | COMBO 4 | LinStatic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000016 | 0.001811 | 8.431 × 10−7 |

| 2 | 52 | COMBO 5 | Combination | −0.000353 | −0.000034 | −0.000027 | 0.000104 | 0.001192 | 0.000186 |

| 2 | 74 | COMBO 5 | Combination | −0.000542 | 0.000035 | −0.000213 | 0.000024 | −0.000253 | 0.000114 |

| 2 | 1 | COMBO 5 | Combination | −0.000608 | 0.000033 | −0.00029 | −0.000997 | −0.002713 | 0.000239 |

| 2 | 56 | COMBO 5 | Combination | 0 | 0 | 0 | −0.0003 | 0.000202 | −4.024 × 10−6 |

| Type | Crane Model | Max. Working Radius [m] | Working Range (Height) [m] | Max. Width with Stabilisation at 100% Extension [m] | Cost [USD/h] | Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spider | URW 376 | 14.45 | −77.07–14.45 | 4.44 | 43.48 | ✓ | ⨯ |

| Spider | URW 506 | 15.71 | −86.57–15.71 | 5.94 | 48.54 | ✓ | ⨯ |

| Spider | URW 295 | 8.41 | −46.8–8.41 | 3.935 | 41.02 | ✓ | ⨯ |

| Truck | HIAB XS 288 | 12.685 | 3–12.69 | 45.13 | ✓ | ⨯ | |

| Truck | PM 32 | 14.85 | 0.9–418.4 | 5.465 | 60.89 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Truck | PM 16523 | 9.95 | 1.240–13.19 | 4.7 | 35.71 | ✓ | ⨯ |

| Truck | ATLAS 3323E A5 | 16.49 | 4–18.3 | 6 | 60.89 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Truck | ATLAS AK1652EA3 | 12.25 | −8–12.8 | 4.030 | 35.72 | ✓ | ⨯ |

| Traditional OSC | Proposed OSC | Savings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steel [kg] | 2254 | 1028 | 1226 |

| Cost [USD] | 15,260 | 6959 | 8300 |

| Embodied carbon [tCO2] | 3.60 | 1.64 | 1.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tapia, D.; González, M.; Vera, S.; Aguilar, C. A Novel Offsite Construction Method for Social Housing in Emerging Economies for Low Cost and Reduced Environmental Impact. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416922

Tapia D, González M, Vera S, Aguilar C. A Novel Offsite Construction Method for Social Housing in Emerging Economies for Low Cost and Reduced Environmental Impact. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416922

Chicago/Turabian StyleTapia, Danilo, Marcelo González, Sergio Vera, and Carlos Aguilar. 2023. "A Novel Offsite Construction Method for Social Housing in Emerging Economies for Low Cost and Reduced Environmental Impact" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416922

APA StyleTapia, D., González, M., Vera, S., & Aguilar, C. (2023). A Novel Offsite Construction Method for Social Housing in Emerging Economies for Low Cost and Reduced Environmental Impact. Sustainability, 15(24), 16922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416922