Abstract

This research delved into the correlation between digital platforms and the dynamics of family-school collaboration within the context of parents with young children in Taiwan. It also examined the roles of parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, and online communication in this model. In the context of Taiwan, a research endeavor was undertaken to elucidate the viewpoints of parents with preschool-age children concerning digital platforms and their associated determinants. A Chinese-translated questionnaire included five latent factors: digital platforms, parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, online communication, and family-school partnerships. Employing a partial least-squares technique, we conducted an in-depth examination of the survey data, focusing on the evaluation of questionnaire latent factor reliability and validity within the measurement model. Subsequently, a path analysis was conducted to examine the hypothesized assumptions in the structural model. The findings indicated significant positive effects, with digital platforms enhancing parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, and online communication, ultimately leading to stronger family-school partnerships. Statistical analyses using a robust dataset consistently confirmed the significance of these associations.

1. Introduction

Family-school partnerships aspire to cultivate enduring and efficacious collaborations across all stakeholders within the educational community. These partnerships are founded upon principles of mutual recognition, accountability, and reverence, involving parents, families, educators, and educational institutions. Their collective objective is the preservation of children’s rights and the provision of equitable opportunities [1]. Furthermore, family-school partnerships have demonstrated their capacity to bolster students’ motivation and academic attainment, while concurrently reinforcing the bonds between educational institutions and communities. In the promotion of such collaborations, there is a deliberate deployment of enabling frameworks, including family-school collaboration teams, institutional guidelines and procedures, assistance networks, and community responsibility mechanisms.

The majority of families not only respond to school-initiated initiatives but also actively seek the school’s involvement in addressing the concerns of their young children. When parents perceive nurturing and supportive teacher-child interactions, they are more likely to exhibit initiative and perseverance in soliciting support for their children from the family-school partnership. Their unwavering dedication to fostering their children’s educational progress, coupled with their eagerness to utilize their assets, empowers parents to actively recognize and pursue their goals, rendering them increasingly open and inclined to engage in school-driven endeavors.

The digital era has expanded communication possibilities, especially in the context of teacher-parent relationships and the family-school partnership. Novel media and information technologies offer educators a myriad of avenues through which they can accommodate the preferences and needs of parents [2]. In recent years, the utilization of digital tools and technology has demonstrated its effectiveness in improving communication between teachers and parents, which in turn bolsters parental engagement and contributes to the overall academic advancement of students. The utilization of digital technologies to support parents in health and social care for young children can significantly enhance their internet accessibility through data-free platforms [3]. This measure ensures that parents have equitable access to accurate information and support for the educational nurturing of their young children.

The employment of digital platforms and online communication holds the potential to augment the future academic success of young children and fortify the partnership between parents and educators. This collaboration significantly contributes to the social construction of, and cultural comprehension of intimacy within, the family-school relationship [4]. Digital platforms, namely, search engines and social media, serve as indispensable resources for parents with young children [5]. These platforms enable parents to establish connections with preschools and educators, fostering opportunities for the exchange of experiences related to early childhood education, the sharing of insights regarding the trials and tribulations of parenthood, and active participation in discussions concerning the cognitive and social development of their offspring.

The confluence of parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, and online communication collectively shapes parental perceptions of family-school partnerships. Parental involvement, a multifaceted construct, encompasses the comprehensive support parents offer to facilitate their children’s educational and developmental progress, spanning the domestic and scholastic domains. This support includes the resources parents invest in, offering goods, activities, and experiences to enhance their children’s educational journey, along with their active engagement in school activities and interactions with school personnel [6]. Such involvement not only fosters the dissemination of information and scaffolding for children’s early learning but also integrates parents into the broader educational community [7]. Parental involvement practices, such as interactive games, museum and library visits, and parent-child reading, have been shown to enhance children’s cognitive and academic proficiency. Elevated parental involvement correlates with a heightened development of children’s early literacy, numeracy, and cognitive competencies.

Furthermore, it is crucial to emphasize that favorable teacher-child interactions play a vital role in shaping children’s socio-emotional growth, their preparedness for formal educational experiences, and their ability to maintain consistent academic success [8]. The enhancement of teacher-child interactions strives to ensure that all children are afforded opportunities for high-quality engagement throughout their early educational years [9]. Positive interactions between teachers and children have a notably beneficial influence on the cognitive, social, and emotional development of the latter. These interactions revolve around engaging children in purposeful and goal-oriented communication, while simultaneously encompassing implicit disciplinary processes within the teacher-child dynamic [10]. The conduct and demeanor within these interactions align with the fundamental attributes of quality teacher-child interactions, underscoring the imperative to augment their quality within preschool settings to engender positive outcomes for children.

Online communication through digital platforms and social media likewise presents innovative solutions that can enhance parental comprehension of their young children’s development. Furthermore, it fosters enhanced collaboration, communication, engagement, and motivation between parents and preschool institutions [11]. Online communication offers readily accessible and effective resources for parenting, contributing to the adoption and implementation of innovative educational practices.

Most preschools in Taiwan have established digital platforms, such as web pages, Facebook, and social media, as tools for communication between parents and teachers and for fostering a partnership between families and schools. These platforms serve as valuable mediums for preschool educators and parents, facilitating the seamless exchange of up-to-the-minute insights on children’s educational development and effective parenting strategies. However, these digital applications are typically designed from the perspective of the preschool and do not consider the needs of parents.

Even with a good digital platform, Taiwanese parents may not necessarily improve their partnership with schools when it comes to young children. To enhance the parent-teacher relationship, it is crucial to investigate how digital platforms can foster interactive effects through interpersonal communication and the influence of digital media. Previous research seldom delved into the comprehensive understanding of these factors. This study addresses this gap by exploring the interconnectedness of the relevant factors.

The value of these applications and the level of cooperation in family-school relationships are also often overlooked. Therefore, this study not only examines the implementation of family-school cooperation but also investigates the impact of digital platforms and related factors on parents’ partnerships with preschools.

1.1. Relationship between Digital Platforms and Parental Involvement

Digital platforms represent a groundbreaking technological advancement, allowing individuals to effortlessly avail themselves of a multitude of services via mobile applications at an economical price point. They offer a swifter, more convenient, and economically efficient means to tap into a wide array of online services from diverse service providers [12]. These platforms can adapt to an individual’s changing needs and retain them as users. By using digital platforms that consider people’s need for autonomy, social connection, and agency, they can develop and adopt healthy habits, behaviors, and learning styles, while also monitoring their progress over time [13].

Digital platforms have the potential to elevate educational quality, as they can be continually optimized through data-driven algorithms, ensuring they remain adaptable to unique needs and evolving standards [14]. This applies to parents using digital apps for interactive, mobile, and smart information access, enjoying these experiences [15]. They select their preferred platform to find media that meets their parenting and education needs. These channels offer real-time updates on the preschool’s status, meeting parents’ and teachers’ needs [16]. These applications not only provide improved digital communication, feedback, and support for parents and teachers but also strengthen their social connections.

These platforms, including various social media and education-related apps, facilitate communication and the exchange of ideas related to parenting and early childhood education, offering essential support to parents of young children [17]. These digital methods are now more frequently employed as standalone or supplementary interventions [18]. A multitude of digital interventions within the realm of mental health have consistently demonstrated their efficacy in fostering mental well-being awareness, enhancing emotional intelligence, honing stress-coping skills, bolstering problem-solving proficiencies, fortifying adaptive strategies, and facilitating the process of seeking professional support [19].

Digital platforms have demonstrated considerable promise in augmenting parental engagement for the purpose of bolstering the educational progress, cognitive growth, emotional health, and social competencies of young children within the preschool and family contexts. Parental involvement refers to parents engaging in various activities that support their children’s development [20]. This includes participating in school and home activities, communicating with the school, helping with homework, volunteering, and being involved in school decision-making.

Parental involvement includes participating in preschool activities, making decisions, communicating with the preschool, and engaging in educational activities at home [21]. In the realm of early childhood education, these platforms enhance the educational experience for young children. They serve as conduits for knowledge dissemination, encourage effective information management, expand educational horizons, and simplify the acquisition of cognitive skills, concepts, and educational resources in the preschool setting [22]. Engaging parents in educational endeavors has demonstrated a favorable impact on the early educational preparedness of young learners, particularly in the domains of academic and interpersonal aptitude [23] Engaging in conversations, offering learning opportunities, and reading to children have a positive impact on their preschool skills and vocabulary [24]. These activities enhance parent-child interactions, and providing assistance with homework and reading is linked to higher literacy assessments and better academic outcomes later on.

Parental involvement in early education is widely acknowledged as crucial. However, we must carefully consider parents’ knowledge and confidence in facilitating their children’s learning. In cases where caregivers face a deficit in knowledge and self-assurance, their capacity to offer pertinent educational experiences becomes diminished [25]. Digital platforms provide a valuable resource for parents seeking enhanced support in assisting their young children with homework and becoming more involved in classroom activities [26]. This active engagement significantly contributes to improving children’s academic achievements.

Moreover, it is crucial to expand on the idea that utilizing digital platforms can boost parental involvement in the educational development of young children. These platforms offer convenient, real-time communication and support for parents, enhancing their involvement in both the preschool and home settings. The adoption of attitudes and behaviors that involve increased participation is believed to have a positive effect on the learning, cognitive growth, and social skills of young children, especially when parents receive guidance and resources via digital platforms.

1.2. Relationship between Digital Platforms and Teacher-Child Interactions

Teacher-child interactions encompass the multifaceted capacities of educators in attending to children’s emotional well-being, nurturing their unique characteristics, fostering child-initiated activities, and deploying adept linguistic methods and tactics to amplify the educational experience [27]. Teacher-child interactions encompass proactive management and cognitive facilitation aspects, which revolve around the establishment of explicit guidelines, the incorporation of concepts, and the application of open-ended inquiries to foster a conducive learning environment [28]. These interactions foster a conducive learning environment, enhance peer engagement, and boost early childhood classroom quality.

High-quality, frequent teacher-child interactions are marked by responsive and sensitive caregiving, aimed at supporting young children in their cognitive, academic, and social development [29]. These interactions can create warm, responsive, and individualized support for self-regulation and engagement in the preschool classroom [30]. The teachers’ proficiency in language, academics, executive function, and social skills significantly influences the quality of these interactions.

They also promote appropriate instructional practices that encourage problem-solving and advanced language skills in young children [31]. Fostering positive and friendly teacher-child interactions in preschool settings promotes holistic child development and contributes to the growth of their social and emotional skills [32].

Teachers’ competence, beliefs, and work environments shape teacher-child interactions [33]. Preschools can provide proactive, professional support to address digital and multi-access environments for teachers and parents. These environments enhance the teachers’ performance, professionalism, and overall instructional competence in preschool and enhance the parents’ trust in teachers [34]. The digital platforms help parents better understand the teachers’ behavior in interactions with their children. This not only fosters positive peer engagement but also creates an environment that supports personalized assistance and a positive classroom atmosphere for young children.

Drawing from the provided information, the integration of digital platforms within early childhood education settings holds the potential to bolster parental confidence in the excellence of teacher-child engagements. These digital resources empower preschool teachers in cultivating a favorable classroom atmosphere, delivering individualized assistance, and championing comprehensive child growth. This, in turn, leads to an improvement in teacher-child interactions in preschool.

1.3. Relationships between Digital Platforms, Parental Involvement, Teacher-Child Interactions, and Online Communication

Parents have indicated that they prefer to have frequent online interactions with teachers, and they believe that the responsibility for building a strong partnership lies primarily with the teachers and preschools. Parents believe that online communication is more conducive to fostering partnerships [35]. They view digital messaging positively because it enables them to receive information about their young children through digital platforms, and it creates a friendly and flowing environment for parent-teacher communication online. Moreover, parents have expressed their trust in teachers and preschools that utilize social media, as it helps establish a solid foundation for the parent-teacher partnership. Additionally, regular communication through digital tools and social media that focuses on discussing young children’s learning milestones has been identified as an effective practice.

Online communication enables users to create and share digital content about their daily lives, which can impact the type of messages shared and the responses received from other users [36]. It satisfies an individual’s desire to connect with peers, share experiences, and cultivate friendships. In today’s digital age, social media platforms on the internet offer individuals an alternative avenue for participating in social engagement, capitalizing on their proficiency and interest in technology mediated through screens [37]. This shift can result in elevated online engagement and a heightened dependence on digital communication for social interaction and forming relationships.

Online communication, centered around the use of digital tools and social media platforms, has become increasingly important for parents and teachers. These platforms facilitate the exchange of information between service providers and families [38]. This type of communication fosters a close social relationship, aligning with the growing emphasis on family engagement and partnership in early childhood education [39]. Through digital platforms, parents and teachers can easily communicate, share updates on a child’s progress, address concerns or issues, and collaborate on strategies to support the child’s learning and development. This form of communication not only strengthens the connection between families and educational institutions but also enables a more efficient and effective approach to fostering the holistic development of the child.

Digital platforms have aided parents in feeling validated in their parenting abilities and observations of their young children [40]. This increased parental involvement empowers them to make decisions and work together with preschool teachers to communicate an underlying rationality and shared values, ultimately enhancing the rationality of educating young children and parenting styles [41]. Online communication has allowed parents to become comfortable with its use and rely on it for social and professional support. The development of parental involvement in collaboration with teachers and preschools ensures that this communication meets the needs of both parties, which is essential for the successful adaptation of young children.

When parents acknowledge preschool teachers for their high-quality teacher-child interactions, they can utilize online communication to facilitate feedback between parents and teachers [42]. The positive attitude towards online communication expressed by both parents and teachers reflects the importance of building and maintaining strong teacher-child interactions [43]. Parents expressed a desire for more feedback about their young children compared to what teachers believed they had provided. Online communication is considered more accessible and effective in promoting parent-teacher partnerships than face-to-face communication.

1.4. Relationships between Parental Involvement, Teacher-Child Interactions, Online Communication, and Family-School Partnerships

The idea of family-school partnerships involves collaborations between schools and families to improve children’s learning outcomes [44]. Family-school partnership entails the harmonious cooperation between parents and educators in nurturing student learning, emphasizing the significance of maintaining a unified language and shared terminology among all stakeholders to amplify comprehension and execution within this domain [45].

The growing need for family-school relationship efforts has involved engaging families in the co-creation of instructional materials. Family-school partnerships that involve families in program co-creation show promise in addressing how children’s developmental transitions within their families may impact their effectivenesss at school [46]. This partnership can provide valuable resources for school-based learning and establish new connections between family and school, with a focus on fostering family-supportive and inclusive partnerships that offer more opportunities to promote the educational development of young children in preschools [47].

Effective collaborations are defined by a foundation of mutual regard, common objectives, and a comprehensive comprehension of the roles, competencies, and obstacles inherent to each participant. It is an ongoing process that requires follow-up actions, and any missing components can compromise relationships and the effectiveness of partnership efforts [48]. It is not surprising that schools initiating collaborative partnerships yield the most positive experiences, as teachers are professionals who are expected to work positively with students and families. Through proactive involvement with parents, we can create a platform for them to voice their concerns, shape educational priorities, and actualize their hopes for their child. This collaborative approach enables us to establish partnerships characterized by cooperation, ultimately delivering tailored assistance that is highly likely to be embraced and effectively applied.

Educational collaborations between families and schools, which harness the power of mesosystemic factors, encompass joint initiatives undertaken by parents and educators to promote a child’s academic progress and socio-emotional development [49]. Effective collaboration between families and schools holds the potential to significantly enhance the academic and socio-emotional growth of young learners. Parental participation in early childhood education is intimately linked to reaping the benefits of a strong alliance between families and educational institutions. This partnership provides support for both the development of skills and motivation [50]. Successful parental involvement necessitates the exchange of knowledge and information with teachers, emphasizing the significance of collaboration between parents and teachers as partners.

The growth and maturation of young learners are intricately shaped by their experiences both within the home and at school [51]. Microenvironments, characterized by direct teacher-child interactions, wield a substantial and immediate influence on their developmental trajectory [52]. When parents view these interactions through the appropriate interface and work to improve their children’s development, they can establish an active family-school partnership that promotes positive academic achievement, better study habits, and higher educational aspirations.

Online communication provides greater accessibility and convenience for parents to engage with and gain support from stakeholders [53]. It has the potential to empower parents in promoting their young children’s well-being and encouraging them to embrace innovative efforts by educators and service providers to foster a collaborative relationship between parents and preschools.

Online communication involves parents in preschool activities and provides valuable information on supporting young children’s learning at home [54]. The dynamic exchange of knowledge between schools and households fosters a productive involvement and establishes a reciprocal approach between home and school, aimed at cultivating an enriching curriculum that integrates insights and backgrounds from home and the surrounding community. This collaborative development, facilitated through digital communication, harnesses the potential of understanding the daily experiences of young children and harnessing this knowledge to design all-encompassing family engagement initiatives and classroom-based learning endeavors.

1.5. Theoritical Framework

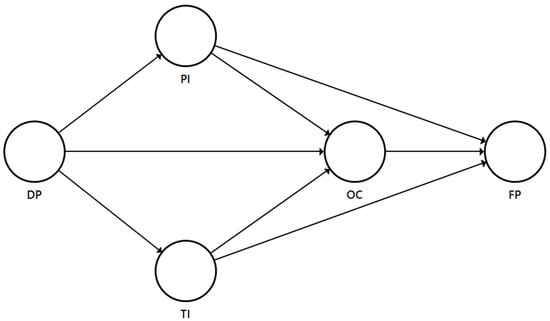

This research explores the complex relationship between digital platforms, parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, online communication, and family-school partnerships in the context of preschool for parents with young children in Taiwanese preschools. Drawing on theoretical reviews and literature analysis, we will propose the positive impact of digital platforms on parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, and online communication. Additionally, we will examine the reciprocal influences between parental involvement and online communication, teacher-child interactions and online communication, parental involvement and family-school partnerships, teacher-child interactions and family-school partnerships, and online communication and family-school partnerships. With these considerations in mind, we present the following hypotheses:

H1.

Digital platforms have a positive impact on parental involvement.

H2.

Digital platforms have a positive impact on teacher-child interactions.

H3.

Digital platforms have a positive influence on online communication.

H4.

Parental involvement has a positive influence on online communication.

H5.

Teacher-child interactions have a positive impact on online communication.

H6.

Parental involvement has a positive impact on family-school partnerships.

H7.

Teacher-child interactions have a positive impact on family-school partnerships.

H8.

Online communication has a positive impact on family-school partnerships.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample Characteristics

This study focuses on parents of young children in Taiwan. Numerous preschools in Taiwan utilize websites and social media to engage with parents. On the one hand, preschool administrators and teachers regularly communicate educational information and administrative updates to parents. On the other hand, these platforms serve as real-time communication tools for interaction with parents. While many parents have face-to-face interactions with preschool teachers during pick-up and drop-off or parenting lectures, their limited physical interactions due to work lead them to predominantly use social media for discussing their young children’s learning and development with teachers. Consequently, most parents are well-acquainted with the practical applications of digital technology and social media in enhancing the effectiveness of family-school partnerships.

An initial group of 450 parents of young children from Taiwan participated in the study. Using the Taiwanese preschool roster, the researchers selected preschools and contacted the principal by phone to confirm their willingness to assist in distributing the questionnaire. Once the preschool principal agreed, the researchers visited the preschool to distribute the questionnaire to parents who were willing to participate.

After excluding incomplete or missing data, the final sample consisted of 368 anonymous parents. The survey had an impressive response rate of 81.8%. A significant portion of the participants, constituting 52% of the sample, identified as mothers, with the remaining 48% being fathers. The largest age group among the respondents (46%) was between 31 and 40 years old, followed by the group of 21 to 29-year-olds (38%). Regarding education, 65% of the respondents had college degrees, 25% held high school degrees, and 10% had postgraduate qualifications. In terms of employment, the majority of respondents (42%) worked in the services industry, while the next group (28%) were employed in business. Table 1 indicates the distributions of sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Distributions of sample characteristics.

2.2. Measurement Instrument

In the study we undertook, we delved into an examination of parental perspectives on the interplay between digital platforms and the collaboration between households and educational institutions for young children. To carry out this study, we created a questionnaire called the “Family-School Partnership for Parents Survey” (FSPPS) that was specifically designed in Chinese. We developed the variables and underlying factors of the FSPPS by thoroughly examining the existing literature and theories. Following this, we refined the survey instrument with insights and suggestions from three distinguished authorities and specialists in the realms of digital technology, early childhood pedagogy, and parental guidance.

The FSPPS had five main aspects: “digital platforms,” “parental involvement,” “teacher-child interactions,” “online communication,” and “family-school partnership.” The survey originally had 28 observable elements, with each aspect having five or six variables. Participants were instructed to express their degree of concurrence with the survey inquiries employing a five-point Likert scale, which spanned from 1, signifying “strongly disagree,” to 5, signifying “strongly agree.” Now, let us delve into the explanations of the five main aspects included in the FSPPS.

1. Digital platforms (DP) involves assessing parents’ attitudes towards using digital tools for parenting and early childhood education, as well as their practical applications in enabling timely updates, communication, and support for both parents and teachers. The variables examined in the context of digital platforms are based on previous studies [12,13,14]. For instance, statements such as “I believe that digital platforms are beneficial for my child’s education” or “I am content with the educational content provided on digital platforms” or “I perceive digital platforms as a means of enhancing parent-teacher communication” or “Overall, I am satisfied with the quality of digital platforms available to me” are considered.

2. Parental involvement (PI) involves assessing parents’ willingness to participate in preschool events, make educational decisions, maintain communication with the preschool, and engage in educational activities at home. The variables examined in relation to parental involvement are based on previous studies [21,22,23]. For instance, examples include “I attend parent-teacher conferences and preschool meetings as scheduled,” or “I assist my child with homework and preschool assignments,” or “I am open to providing additional support or resources to help my child succeed in preschool,” or “I feel supported by my child’s preschool in my efforts to be involved in their education.”

3. Teacher-child interactions (TI) encompasses the evaluation of parental perspectives on educators’ abilities to cater to the emotional well-being of children, embrace diversity, foster child-initiated activities, and employ proficient methods of communication and pedagogical approaches [27,28,29]. The variables examined in the context of digital platforms are based on previous research. For instance, some examples include “The teacher demonstrates care and concern for my child,” or “My child and the teacher communicate in a friendly manner,” or “The teacher tailors attention to my child’s specific needs,” or “The teacher fosters a warm and welcoming classroom environment.”

4. Online communication (OC) involves assessing parents’ willingness to utilize digital platforms and social media for exchanging information, participating in discussions, and sharing content related to preschool education and the development of young children. The variables observed in the context of digital platforms are based on previous studies [36,37,38]. For instance, statements such as “I find online communication with teachers more convenient than traditional in-person meetings” or “Online communication helps bridge the gap between home and school” or “Online communication has enhanced the quality of feedback and information I receive from teachers” or “I am satisfied with the frequency of online communication between school and home” are considered.

5. Family–school partnership (FP) involves assessing parents’ willingness to engage in collaborative efforts between schools and families to improve young children’s learning outcomes. The variables examined in relation to digital platforms are based on previous research [45,46,47]. For instance, statements such as “I feel welcomed and encouraged to participate in my child’s school activities and events” or “The school provides resources and materials that assist me in supporting my child’s learning outside of school” or “I am encouraged to join parent-teacher associations or similar groups” or “The school actively collaborates with parents to establish a positive learning environment for students” are considered.

Drawing on theoretical exploration and hypothesis construction, we proposed hypotheses H1–H8, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

2.3. Data Analysis

We analyzed the survey data using the technique of partial least squares to investigate the influence of latent factors, based on our theoretical hypotheses [55,56]. To assess the validity and reliability of the FSPPS measurement model, we performed confirmatory factor analysis using the statistical software SmartPLS 3 [57]. We determined the factor loadings for different variables and tested their statistical significance using 5000 bootstrapping resamples. To ensure the validity and reliability of our research, we considered essential criteria such as Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Moreover, we evaluated the discriminant validity in the measurement model by applying the Fornell–Larcker criterion and assessing the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT).

In the structural model, we discerned the presence of multicollinearity among latent factors by utilizing the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Furthermore, we conducted a comprehensive assessment of various metrics, including R-squared (R2), Adjusted R-squared (Adj. R2), Q-squared (Q2), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), both for latent factors and the theoretical model as a whole.

Following the path regression analysis, we employed effect sizes (f2) to delve into the specific contributions of each latent factor. To ensure the robustness of our findings, we subjected the data to a rigorous process, involving 5000 bootstrapping resamples, to evaluate the estimates and their statistical significance in relation to total, direct, and indirect effects, all aimed at rigorously testing the hypothesized relationships.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate the survey items within the FSPPS. Any variables with factor loadings less than 0.700 were excluded from the analysis, reducing the original 28 observed variables to a final set of 20 items in the FSPPS. These retained 20 variables displayed mean scores ranging from 3.503 to 4.609, with standard deviations spanning from 0.513 to 1.063. Kurtosis values were observed within the range of −1.046 to 1.944, while skewness values ranged from −1.021 to 0.056, all of which fell within the acceptable range of −2 to +2. Standardized factor loadings for each variable are provided in Table 2 and ranged from 0.732 to 0.930. Regarding the significance testing using the bootstrapping method with 5000 resamplings, it was determined that all factor loadings yielded t statistics exceeding 3.29, indicating their statistical significance (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

The mean, SD, factor loading, and t value in FSPPS.

In Table 3, the assessment of the validity and reliability of latent factors in the FSPPS reveals strong statistical consistency. Specifically, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients fall within the range of 0.863 to 0.902, all surpassing the theoretical threshold of 0.800. Similarly, the rho_A values exhibit robust internal consistency, ranging from 0.877 to 0.926, also exceeding the 0.800 threshold. Moreover, the composite reliability (CR) scores demonstrate remarkable reliability, spanning from 0.907 to 0.932, comfortably exceeding the critical 0.800 threshold. Finally, the average variance extracted (AVE) scores, ranging from 0.710 to 0.773, all exceed the theoretical threshold of 0.500. These findings affirm that all the measures of validity and reliability in the FSPPS align with established criteria, validating the instrument’s robustness.

Table 3.

Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, CR, AVE.

Table 4 presents the relationships between latent variables within the FSPPS framework, with values ranging from 0.843 to 0.879. The diagonal of the table displays the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent factor. The off-diagonal elements represent the correlation coefficients between the latent factors. The correlation coefficients for these latent factors consistently fell below the square root of the AVE, ranging from 0.052 to 0.274. These findings strongly support the idea that the FSPPS exhibits solid discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity: Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 5 provides a thorough analysis conducted through the HTMT approach to evaluate discriminant validity within the FSPPS framework. All HTMT coefficients fell below the established threshold of 0.850, with values ranging from 0.277 to 0.735. These results affirm the strong internal and external consistency present within the FSPPS. Overall, these assessments underscore the sound measurement of latent factors in the FSPPS, the robustness of its convergent validity, and the statistically significant establishment of appropriate discriminant validity.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity: Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

3.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

Table 6 presents the collinearity statistics evaluated using VIF (Variance Inflation Factor). The VIF values for the latent factors varied from 1.000 to 1.246, all comfortably below the threshold of 5. These results indicated that multicollinearity among the latent factors in the FSPPS did not have any significant effects, suggesting a low level of multicollinearity.

Table 6.

The collinearity statistic (VIF) results.

Table 7 presents the assessment of the structural model’s quality using the FSPPS. The metrics, including R2 (ranging from 0.060 to 0.594), Adj. R2 (falling between 0.058 and 0.591), and Q2 (ranging from 0.043 to 0.413), collectively indicate a strong level of structural validity. Moreover, the SRMR score of 0.102 shows a reasonable alignment between the empirical data and the hypothesized model in the context of the FSPPS.

Table 7.

The structural model results.

Table 8 presents an overview of the effect size associated with the latent factors in the FSPPS framework, ranging from 0.024 to 0.442. Effect sizes, represented by f2 values like 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, are typically classified as indicating small, medium, and large effects, respectively. Most f2 values between the latent factors in the structural model of the FSPPS showed small to medium practical significance.

Table 8.

The effect size (f2) results.

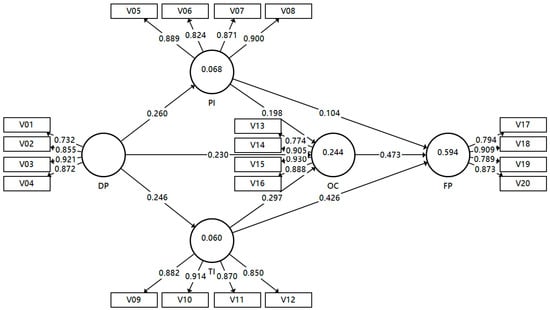

Figure 2 presents the standardized regression coefficients and the measures of explained variance. The digital platforms component accounts for 6.8% of the variance in parental involvement, with a standardized regression coefficient of 0.260. When considering the digital platforms, it explains 6.0% of the variability in teacher-child interactions, with a standardized regression coefficient of 0.246. The latent factors of digital platforms, parental involvement, and teacher-child interactions combined explain 24.4% of the variance in online communication, with standardized regression coefficients of 0.230, 0.198, and 0.297, respectively.

Figure 2.

Structural model.

The latent factors of parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, and online communication collectively account for a significant 59.4% of the variability in family-school partnerships. The standardized regression coefficients for these factors are 0.104, 0.426, and 0.473, respectively. To assess the significance of these results, the bootstrap technique was used with 5000 resamplings. The results indicated that all t statistics exceeded 1.96, indicating statistical significance at a p < 0.05 threshold.

3.3. Assessment of Total Effects

Based on the results presented in Table 9, H1 posits that digital platforms have a significant positive influence on parental involvement in the education of young children, with a standardized total effect of 0.260. Digital platforms offer convenient, real-time communication and support for parents, enhancing their participation in preschool and home environments. This heightened involvement is believed to positively impact young children’s learning, cognitive development, and social skills, particularly when parents receive guidance and resources through digital channels.

Table 9.

Total effects of path analysis in structural model.

H2 proposes that the use of digital platforms has a positive impact on teacher-child interactions in preschool settings. These interactions are critical for children’s emotional, cognitive, and social development. Digital tools can enhance teacher performance, provide parents with insights into their child’s interactions with teachers, and ultimately contribute to a positive classroom atmosphere and personalized support for young children. The standardized total effect of 0.246 suggests a statistically significant influence of digital platforms on teacher-child interactions.

H3 proposes that digital platforms have a significant positive impact on online communication for parents of young children, with a standardized total effect of 0.355. This hypothesis is grounded in the idea that parents find online communication through digital tools and social media conducive to building strong partnerships with teachers and preschools. Parents value the ease of receiving information and sharing their child’s progress through these platforms, believing it fosters a friendly and efficient online environment for parent-teacher communication. Furthermore, the hypothesis acknowledges the prevailing societal transition towards a greater dependence on digital communication for social interaction and relationships, underscoring the significance of digital platforms in enhancing the exchange of information between parents and educators in the context of early childhood education.

H4 posits that increased parental involvement significantly affects online communication among the parents of young children, with a standardized total effect of 0.198. This suggests that, as parents become more engaged in their children’s education and collaborate with teachers and preschools, they are more likely to use online communication tools for social and professional support. This enhanced involvement fosters effective communication and aligns parenting styles with educational goals.

H5 suggests that teacher-child interactions significantly influence online communication among parents of young children, with a standardized total effect of 0.297. When parents appreciate high-quality teacher-child interactions in preschools, it enhances their use of online communication to facilitate feedback between parents and teachers. Positive attitudes towards online communication indicate the importance of strong teacher-child interactions. This hypothesis implies that improving teacher-child interactions can positively impact parent-teacher online communication.

H6 suggests that parental involvement significantly contributes to family-school partnerships for parents of young children, with a standardized total effect of 0.197. Family-school partnership is about parents and teachers collaborating to support student learning, creating a bridge between home and school. The proposition suggests that active parental involvement in their children’s educational journey exerts a constructive impact on the quality and efficacy of the collaboration between families and educational institutions. Consequently, this collaborative effort holds the potential to bolster the academic and socio-emotional growth of young learners during their time in preschool and throughout their educational trajectory.

H7 posits that the quality of teacher-child interactions significantly impacts the establishment of a strong family-school partnership for parents of young children, with an estimated total effect of 0.567. This suggests that positive teacher-child interactions can foster a collaborative relationship between families and schools, leading to improved academic performance, study habits, and educational goals for the children.

H8 suggests that online communication significantly influences family-school partnerships for parents of young children. Online communication enhances accessibility, empowering parents to support their children’s well-being. It fosters a synergy between parents and early childhood education institutions, fostering a holistic home-to-school perspective, jointly shaping comprehensive family involvement initiatives, and fortifying collaborative family-school connections, resulting in a standardized cumulative impact of 0.473.

Statistical significance analyses were performed on various metrics, encompassing the direct effect, indirect effect, and total effect, employing a robust dataset involving 5000 iterations of bootstrapping. The results of these evaluations consistently demonstrated p-values below the threshold of 0.05, thereby confirming the statistical significance of the envisioned associations scrutinized within the path analysis framework.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the viewpoints of parents of young children regarding digital platforms and their impact on the family-school partnership. We investigated how these perspectives affected parental involvement, interactions between teachers and children, and online communication with parents, preschools, and teachers. The analysis, conducted using partial least squares in a hypothesized model, produced significant findings that confirmed the accuracy of both the measurement and structural models. This investigation offered empirical evidence in support of the proposed hypotheses (H1 to H8), demonstrating the statistical significance of the relationships within the model.

This study aimed to explore the connection between digital platforms, parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, online communication, and family-school partnerships in preschool settings for Taiwanese parents of young children. The study’s findings indicated that parents of young children perceived digital platforms as having a positive impact on parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, and online communication in preschools. This suggests the potential advantages of integrating digital tools into preschool education to enhance these areas.

Furthermore, parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, and online communication had positive impacts on online communication and family-school partnerships. This emphasizes the interconnectedness of these factors and underscores the significance of a collaborative approach between parents, teachers, and digital platforms to promote effective family-school partnerships in preschools.

This study is valuable for its construction of an integrated family-school partnership model. It investigates the influence of digital platforms, parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, and online communication on the perceptions of the family-school partnership among Taiwanese preschool parents. While previous studies have mainly examined specific relationships among these factors [48,49,50], there was a limited exploration of the attitude model of parents of young children towards the family-school partnership from a comprehensive perspective. Addressing this gap, our study delves into the overall perspectives of parents of young children regarding the family-school partnership model.

Furthermore, this study specifically examines the communication impact of interpersonal interaction and digital media. It not only delves into the interactive attitudes regarding parental involvement in preschool practices and teacher-child relationships but also underscores the communicative significance of digital platforms and social media. Past research has overlooked the concurrent benefits of offline and online integrated communication [8,9,10,11]. This study addresses this gap by investigating parents’ perspectives on the use of both offline and online digital communication. The goal is to enhance family-school partnerships and boost the efficacy of early childhood education, aligning with the expectations of Taiwanese parents for their young children.

This study’s findings highlight the potential of digital platforms in preschool education and emphasize the importance of fostering positive interactions and communication among parents, teachers, and children to create effective family-school partnerships. All hypotheses are supported by the sample data through the analysis of a partial least-squares model and have achieved statistical significance.

According to the findings, digital platforms are crucial in facilitating communication between parents and preschools, thus enhancing the partnership between families and schools. The researchers recommend that preschools establish user-friendly and interactive digital platforms to promote communication between teachers and parents. Various engaging mobile devices and applications can be developed and provided to parents, enabling them to engage in immediate and interactive communication regarding educational information. This will ultimately boost parents’ confidence and ability to collaborate effectively with preschools.

The possible model of the digital platform in preschool should be easy to use and useful. With this customer-oriented digital platform, parents can benefit from accessing a supportive online community and understanding how digital platforms can contribute to their young children’s learning and development. The provision of useful parenting information in the digital platform can help parents develop their cognitive and social parenting and educare skills constructively. This digital resource enhances parental self-assurance, while simultaneously assisting early childhood educators in articulating their pedagogical philosophies and caregiving approaches to foster the well-rounded development of young learners.

Based on the results, parents’ consideration of parental involvement in preschool and their perception of teacher-child interactions play common roles in influencing the development of family-school partnerships. We propose that preschool educators can implement strategies like offering commendations, delivering constructive feedback, and employing attention-enhancing methods to motivate parents to actively participate in their children’s educational journey. The strong association between parents’ experiences and teachers’ instructions can help young children with the development of academic performance, motivation, interests, and self-efficacy. To foster the educational development of young children, it is imperative that we encourage and empower parents to actively engage in their child’s learning journey. This entails promoting parental participation in early childhood education and integrating it seamlessly into the daily routines of preschool-aged children.

The results show that teacher-child interactions are crucial for influencing parents’ family-school partnerships in preschool. We recommend that preschool teachers establish a friendly and helpful connection with caring and reflective instructions to emphasize the significance of emotionally supportive interactions in promoting positive classroom environments and teacher-child relationships. Preschool teachers are encouraged to engage in friendly and diverse teacher-child interactions, including warm contact, low authority, attention to children’s developmental level, scaffolding, and providing pedagogical assistance to create well-organized and effective classrooms.

Online communication also plays an important role in developing family-school partnerships, as shown by the above results. Our suggestion is that preschool educators maintain a steady flow of communication with parents regarding their toddlers’ achievements, daily schedules, and upcoming educational engagements via digital communication platforms. This interactive online model helps parents feel engaged and valued in the preschool’s online environment. We strongly advocate for teachers to extend invitations to parents for collaborative and recurrent activities within the preschool setting. These gatherings can center around purpose-driven endeavors concerning the advancement of young learners and the curriculum. Most importantly, maintaining an open online dialogue mechanism and actively listening to parents’ requests is crucial, as their needs and preferences may vary. By implementing these strategies, a strong parent-teacher partnership can be effectively built, engaging both parents and preschools.

For policymaking, the recommendations suggest a focus on creating user-friendly digital platforms in preschools, fostering parental involvement, and promoting teacher-child interactions. Policymakers should consider allocating additional budgetary resources to support the integration of digital technology in preschools, and supplementing resources or tools for developing interactive platforms through digital technology or social media. Furthermore, policies should underscore the importance of training preschool teachers to foster positive interactions with parents using digital tools. In educational practices, we stress the implementation of strategies to improve online communication, parental involvement, and teacher-child interactions in preschools, highlighting the role of digital technology and social media in facilitating these processes. Preschool teachers should undergo training in effective communication using both online and offline methods and creating positive classroom environments.

Based on the above investigations, the FSPPS, as originally conceptualized in this research model, can be flexibly utilized or adapted to assess the perspectives of parents of young children in preschool for future study. Future researchers can examine the relevant literature on family-school partnerships and digital applied practices in preschool to develop new latent factors and survey items. They can design and evaluate possible hypotheses to identify useful alternatives for the family–school partnership. Additionally, prospective inquiries should include qualitative methodologies such as interviews with preschool teachers or partners with young children, as well as on-the-ground field observations in preschool, to analyze real and contextual evidence and gain meaningful insights. These diverse research approaches can significantly enhance the landscape of family-school partnerships and early childhood education, thereby promoting greater collaboration between parents and teachers through meaningful digital applications and communicative mechanisms.

This study employed a questionnaire survey to gather cross-sectional data on the issue from parents of young children. However, it could not delve into longitudinal effects or changes across various cultural or socioeconomic backgrounds. The researchers recommend future exploration through longitudinal studies or comparisons of variables across diverse individual backgrounds. Conducting differential analyses and comparative studies on parents’ perspectives regarding family-school partnerships and related factors can enhance our comprehension of this issue.

The degree of digital technology usage in preschool education varies across countries and regions. In Taiwan, users generally exhibit high levels of access and engagement with digital technology and related innovations. Specifically, Taiwanese parents of young children tend to have moderate-to-high preferences for utilizing digital technology and social media. They are also more inclined to interact with preschools through social media platforms and mobile apps. It is important to note that research findings in Taiwan may not be universally applicable to other countries or regions. Additionally, the diverse configurations of digital technology and social media usage in different areas, along with international variations in attitudes and behaviors, should be taken into consideration. The researchers recommend future studies that conduct comparative analyses across different countries or regions to explore international variations in the implementation of digital technology for early childhood education.

5. Conclusions

This study extensively explored the connection between digital platforms, parental involvement, teacher-child interactions, online communication, and family-school partnerships in preschool settings. The researchers formulated hypotheses H1 to H8 through theoretical reflections and examined parents’ perceptions of the relationship between family-school partnerships and associated factors. The statistical results of the FSPPS survey confirmed hypotheses H1 to H8 through partial least squares.

Taiwanese parents of young children perceive digital platforms as an important tool for heightened engagement in their young children’s educare journey, fostering improved teacher-child interactions, and positively influencing online communication with preschool teachers. Additionally, parental involvement and teacher-child interactions were found to positively influence online communication, which, in turn, contributes to the development of a stronger family-school partnership. Digital platforms, along with related applications and interpersonal practices, play a significant role in promoting effective preschool education and fostering collaboration between parents, teachers, and schools.

Digital platforms offer substantial potential as valuable tools for promoting sustainable development in preschool education. They serve to mitigate the constraints of physical barriers and facilitate efficient communication, thereby aligning with the core tenets of sustainability. By engaging parents in their children’s educational journey through digital platforms, a sense of community is fostered, culminating in a shared responsibility for instilling sustainable practices within preschool settings.

The establishment of robust partnerships between families and schools is paramount for nurturing comprehensive child development. Embracing a collaborative paradigm that involves parents and preschool institutions can significantly enhance the effectiveness of sustainability education. To advance the utilization of online spaces mediated by digital tools and social media among parents and preschool educators, it is imperative to exercise judicious use of digital resources. The integration of digital platforms into the preschool teaching and learning milieu holds the potential to engender enduring transformations within our digital society and to empower parents as proactive participants in the educational process of their children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.-C.H.; Methodology, P.-C.H.; Software, P.-C.H.; Validation, P.-C.H.; Formal analysis, P.-C.H. and R.-S.C.; Investigation, P.-C.H. and R.-S.C.; Resources, R.-S.C.; Data curation, R.-S.C.; Writing—original draft, R.-S.C.; Writing—review & editing, And R.-S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because of minimal risk, and only non-identifiable human data was used.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sisson, J.H.; Shin, A.M.; Whitington, V. Re-imagining family engagement as a two-way street. Aust. Educ. Res. 2022, 49, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Rivera-Vernazza, D.E. Communicating Digitally: Building Preschool Teacher-Parent Partnerships Via Digital Technologies During COVID-19. Early Child. Educ. J. 2022, 51, 1189–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, L.M.; Naicker, S.N. A Data-Free Digital Platform to Reach Families with Young Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Online Survey Study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2021, 4, e26571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdreich, L. Mediating intimacy: Parent-teacher digital communication and perceptions of ‘proper intimacy’ among early childhood educators. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2023, 32, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruebner, O.; van Haasteren, A.; Hug, A.; Elayan, S.; Sykora, M.; Albanese, E.; Naslund, J.; Wolf, M.; Fadda, M.; von Rhein, M. Digital Platform Uses for Help and Support Seeking of Parents with Children Affected by Disabilities: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e37972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Markowitz, A.J. Can parents do it all? Changes in parent involvement from 1997 to 2009 among Head Start families. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Litkowski, E.; Schmerold, K.; Elicker, J.; Schmitt, S.A.; Purpura, D.J. Parent-Educator Communication Linked to More Frequent Home Learning Activities for Preschoolers. Child Youth Care Forum 2019, 48, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.Y.; Wang, S.; Song, Y.Q.; LoCasale-Crouch, J. Exploring the complex relationship between developmentally appropriate activities and teacher-child interaction quality in rural Chinese preschools. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, A.H.; Ansari, A.; Grimm, K.J.; Pianta, R.C. Power of Two: The Impact of 2 Years of High Quality Teacher Child Interactions. Early Educ. Dev. 2019, 30, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilfyr, K.; Aspelin, J.; Lantz-Andersson, A. Teacher-Child Interaction in a Goal-Oriented Preschool Context: A Micro-Analytical Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.L.; Jandigulov, A.; Snezhko, Z.; Volkov, L.; Dudnik, O. New Technologies in Educational Solutions in the Field of STEM: The Use of Online Communication Services to Manage Teamwork in Project-Based Learning Activities. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi, M.; Sheikh, A.; Tourani, N.; Bagheri, R. Service Delivery and Branding Management in Digital Platforms: Innovation through Brand Extension. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 2022, 7159749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippoliti, N.; Sekamana, M.; Baringer, L.; Hope, R. Using Human-Centered Design to Develop, Launch, and Evaluate a National Digital Health Platform to Improve Reproductive Health for Rwandan Youth. Glob. Health-Sci. Pract. 2021, 9, S244–S260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawji, A.; Li, E.; Dunsmuir, D.; Komugisha, C.; Novakowski, S.K.; Wiens, M.O.; Vesuvius, T.A.; Kissoon, N.; Ansermino, J.M. Smart triage: Development of a rapid pediatric triage algorithm for use in low-and-middle income countries. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 976870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johari, S.; Noordin, W.N.W.; Mahamad, T.E.T. WhatsApp Conversations and Relationships: A Focus on Digital Communication Between Parent-Teacher Engagement in a Secondary School in Putrajaya. J. Komun. Malays. J. Commun. 2022, 38, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.; Kumpulainen, K.; Smith, C. Children’s digital play as collective family resilience in the face of the pandemic. J. Early Child. Lit. 2023, 23, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, E.; Allabyrne, C.; Keenan, J.R. Delivering clinical evidence-based child-parent interventions for emotional development through a digital platform: A feasibility trial. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeland, L.; O’Reilly, M.; Fleury, J.; Adams, S.; Vostanis, P. Digital Social and Emotional Literacy Intervention for Vulnerable Children in Brazil: Participants’ Experiences. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2022, 24, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madi, D.; Doumit, M.A.A.; Hallal, M.; Moubarak, M.M. Outlooks on using a mobile health intervention for supportive pain management for children and adolescents with cancer: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, Ö.; Bayindir, D. The relation between parental involvement and school readiness: The mediating role of preschoolers’ self-regulation skills. Early Child Dev. Care 2022, 192, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatierra, L.; Cabello, V.M. Starting at Home: What Does the Literature Indicate about Parental Involvement in Early Childhood STEM Education? Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.Y. Family Income, Parental Education and Chinese Preschoolers’ Cognitive School Readiness: Authoritative Parenting and Parental Involvement as Chain Mediators. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 745093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrett, R.L.; Coba-Rodriguez, S. “Whatever I Can Imagine, We Did It”: Home-Based Parental Involvement Among Low-Income African-American Mothers With Preschoolers Enrolled in Head Start. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2019, 33, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.Y.; Hackett, R.K.; Webster, L. Chinese Parental Involvement and Children’s School Readiness: The Moderating Role of Parenting Style. Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 31, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, S.; Stites, M.; Dowling, R. Learning at home: What preschool children’s parents do and what they want to learn from their children’s teachers. J. Early Child. Res. 2021, 19, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Riley, D. Accelerating Early Language and Literacy Skills Through a Preschool-Home Partnership Using Dialogic Reading: A Randomized Trial. Child Youth Care Forum 2021, 50, 901–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.X.; Hu, B.Y.; Wu, H.P.; Zhang, X.; Davis, A.N.; Hsiao, Y.Y. Differential associations between extracurricular participation and Chinese children’s academic readiness: Preschool teacher-child interactions as a moderator. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 59, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Alamos, P.; Turnbull, K.L.P.; LoCasale-Crouch, J.; Howes, C. Examining individual children’s peer engagement in pre-kindergarten classrooms: Relations with classroom-level teacher-child interaction quality. Early Child. Res. Q. 2023, 64, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchinal, M.; Garber, K.; Foster, T.; Bratsch-Hines, M.; Franco, X.; Peisner-Feinberg, E. Relating early care and education quality to preschool outcomes: The same or different models for different outcomes? Early Child. Res. Q. 2021, 55, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, N.M.; Abenavoli, R.M. Problem behaviors at the classroom-level and teacher-child interaction quality in Head Start programs: Moderation by age composition. J. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 99, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulotsky-Shearer, R.J.; Fernandez, V.A.; Bichay-Awadalla, K.; Bailey, J.; Futterer, J.; Qi, C.H.Q. Teacher-child interaction quality moderates social risks associated with problem behavior in preschool classroom contexts. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamos, P.; Williford, A.P. Exploring dyadic teacher-child interactions, emotional security, and task engagement in preschool children displaying externalizing behaviors. Soc. Dev. 2020, 29, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamos, P.; Williford, A.P. Teacher-child emotion talk in preschool children displaying elevated externalizing behaviors. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.Y.; Lim, S.A. The influence of Korean preschool teachers’ work environments and self-efficacy on children’s peer play interactions: The mediating effect of teacher-child interactions. Early Child Dev. Care 2019, 189, 1749–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, C.; Kuusisto, E.; Tirri, K. Finnish and Portuguese Parents’ Perspectives on the Role of Teachers in Parent-Teacher Partnerships and Parental Engagement. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.; Shin, W.; Lwin, M.O. Social Networking Site Use and Materialistic Values Among Youth: The Safeguarding Role of the Parent-Child Relationship and Self-Regulation. Commun. Res. 2019, 46, 1119–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie-Smith, K.; Hendry, G.; Anduuru, N.; Laird, T.; Ballantyne, C. Using social media to be ‘social’: Perceptions of social media benefits and risk by autistic young people, and parents. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 118, 104081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigos, T.; Fenech, M. Early childhood education and care in the app generation: Digital documentation, assessment for learning and parent communication. Australas. J. Early Child. 2021, 46, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalma, I.; Rékai, K. Personal and Online Contact during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Nonresident Parents and their Children in Hungary. Int. J. Sociol. 2020, 50, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; Butler, J.E.; O’Neill, C. Identifying Barriers and Solutions to Increase Parent-Practitioner Communication in Early Childhood Care and Educational Services: The Development of an Online Communication Application. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, K.G.; Brodsgaard, A.; Zachariassen, G.; Smith, A.C.; Clemensen, J. Parent perspectives of neonatal tele-homecare: A qualitative study. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusimäki, A.M.; Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L.; Tirri, K. Parents’ and Teachers’ Views on Digital Communication in Finland. Educ. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 8236786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin, O.; Davidson, S. Riding the tiger: Professional capital and the engagement of Israeli kindergarten teachers with parents’ WhatsApp groups. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2022, 7, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, G.; Kilderry, A. Family school partnership discourse: Inconsistencies, misrepresentation, and counter narratives. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 109, 103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathan, S.C. Predicting family engagement in Early Head Start. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 145, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWayne, C.M.; Melzi, G.; Mistry, J. A home-to-school approach for promoting culturally inclusive family-school partnership research and practice. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.M.; Lee, C.E.; Rios, K. A pilot evaluation of an advocacy programme on knowledge, empowerment, family-school partnership and parent well-being. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, A.; Truscott, J.; O’Byrne, C.; Considine, G.; Hampshire, A.; Creagh, S.; Western, M. Disadvantaged families’ experiences of home-school partnerships: Navigating agency, expectations and stigma. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 25, 1236–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.E.; Sheridan, S.M.; Kim, E.M.; Park, S.; Beretvas, S.N. The Effects of Family-School Partnership Interventions on Academic and Social-Emotional Functioning: A Meta-Analysis Exploring What Works for Whom. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 511–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, J.; Goei, S.L.; Huizinga, M.; De Ruyter, D.J. True partners? Exploring family-school partnership in secondary education from a collaboration perspective. Educ. Rev. 2022, 74, 805–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutullo, O.R.; Sanders-Smith, S.C.; Smith-Bonahue, T.M. School psychology interns’ characterizations of family-school partnerships. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.E.; Reinke, W.M.; Herman, K.C.; Huang, F. Understanding Family-School Engagement Across and Within Elementary-and Middle-School Contexts. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, W.H.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Clancy, E.M.; Westrupp, E.M.; Benstead, M.L.; Yap, M.B.H. Strategies to Increase Uptake of Parent Education Programs in Preschool and School Settings to Improve Child Outcomes: A Delphi Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWayne, C.; Hyun, S.; Diez, V.; Mistry, J. “We Feel Connected horizontal ellipsis and Like We Belong”: A Parent-Led, Staff-Supported Model of Family Engagement in Early Childhood. Early Child. Educ. J. 2022, 50, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 28 October 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).