Cross-Country Analysis of Willingness to Pay More for Fair Trade Coffee: Exploring the Moderating Effect between South Korea and Vietnam

Abstract

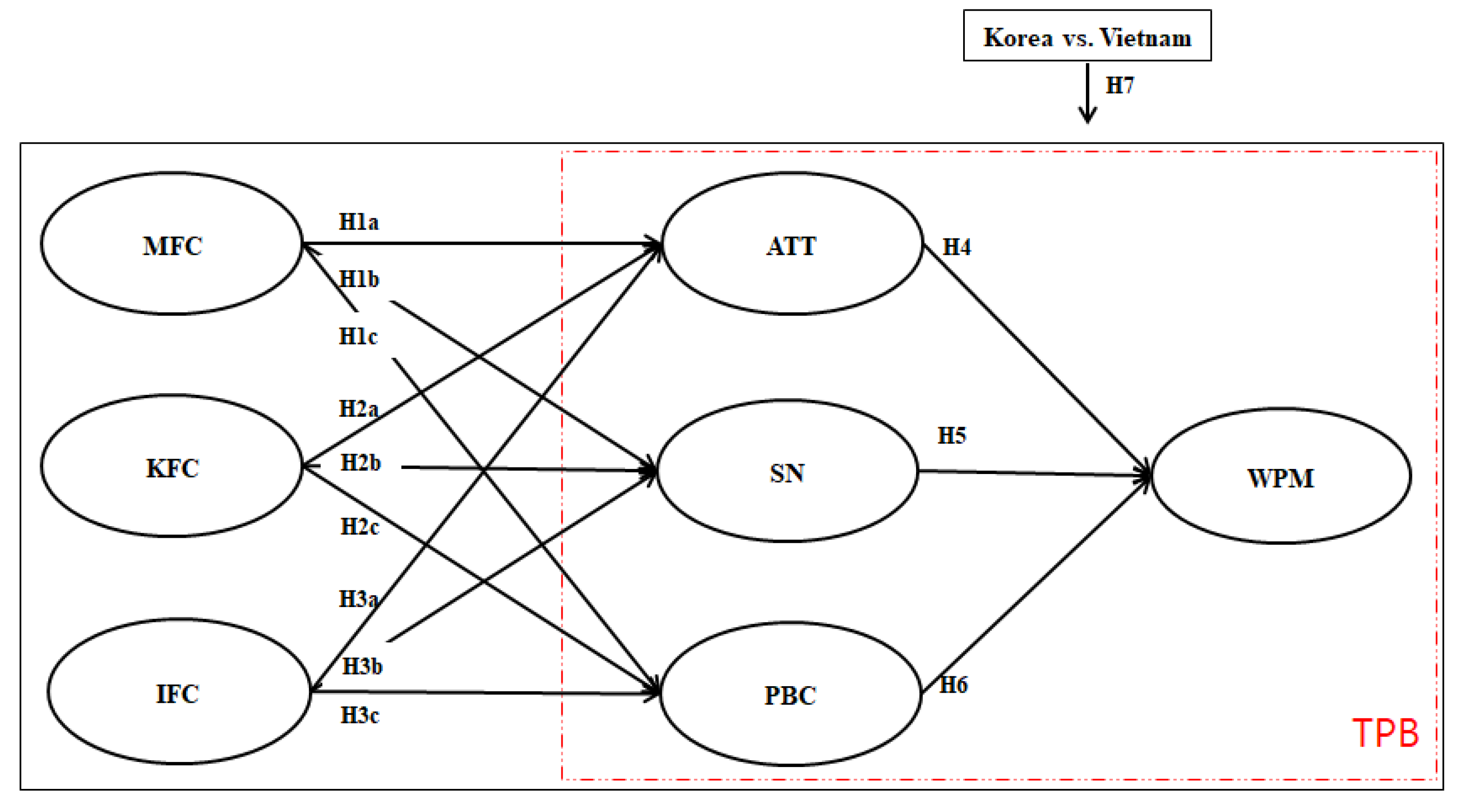

:1. Introduction

- How do consumers in South Korea and Vietnam differ in their willingness to pay more for fair trade coffee?

- What are the internal and external factors influencing consumers’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control regarding increased spending on fair trade coffee in these two countries?

- To what extent do recognized values and additional willingness to pay impact fair trade coffee purchase intentions and actual behavior in South Korea and Vietnam?

- How can the theory of planned behavior (TPB) framework be extended to better understand consumer behavior and decision-making related to fair trade coffee in these specific contexts?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Coffee Market

2.1.1. Korean Coffee Market

2.1.2. Vietnam Coffee Market

2.2. Fair Trade Coffee

2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

2.3.1. Moral Obligation

2.3.2. Knowledge

2.3.3. Involvement

2.3.4. Attitude

2.3.5. Subjective Norms

2.3.6. Perceived Behavioral Control

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model Testing

Moderating Effects of the Customers’ Perceptions of Korea and Vietnam

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicholls, A. Fair trade: Towards an economics of virtue. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M. Understanding consumer resistance to the consumption of organic food. A study of ethical consumption, purchasing, and choice behaviour. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Shiu, E.; Clarke, I. The contribution of ethical obligation and self-identity to the theory of planned behaviour: An exploration of ethical consumers. J. Mark. Manag. 2000, 16, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillani, A.; Kutaula, S.; Leonidou, L.C.; Christodoulides, P. The impact of proximity on consumer fair trade engagement and purchasing behavior: The moderating role of empathic concern and hypocrisy. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 169, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G. The fair trade movement: Parameters, issues and future research. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.; Huybrechts, B. Sustaining inter-organizational relationships across institutional logics and power asymmetries: The case of fair trade. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Rosati, F.C. Global social preferences and the demand for socially responsible products: Empirical evidence from a pilot study on fair trade consumers. World Econ. 2007, 30, 807–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jin, Y.; Shin, H. Cosmopolitanism and ethical consumption: An extended theory of planned behavior and modeling for fair trade coffee consumers in South Korea. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyundai Research Institute. The five trends and prospects of the coffee industry-Growth to about 7 trillion won in the domestic coffee industry! Korea Econ. Dly. Rev. 2019, 848, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S. A Study on the Influence of the Types of Advertising Appeal According to the Degree of Involvement Exercise on the Evaluation of an Extended Brand. Master’s Thesis, Dankook University, Yongin, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- USDA Foreign Agricultural Service Gain Report. 2019. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Coffee%20Semi-annual_Hanoi_Vietnam_11-15-2019 (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Customs, Vietnam. “Trade Analysis. Vietnam Customs. 2015. Available online: https://www.customs.gov.vn/index.jsp?pageId=2281&aid=156914&cid=4099 (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Marsh, A. Diversification by Smallholder Farmers: Viet Nam Robusta Coffee; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2007; Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2012/mar/26/better-future-vietnam-coffee-growth (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Mistiaen, V. A better future is percolating for Vietnam’s coffee. The Guardian. 2012. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiptZui2uiCAxWxVPUHHTwvCnkQFnoECA0QAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.theguardian.com%2Fglobal-development%2Fpoverty-matters%2F2012%2Fmar%2F26%2Fbetter-future-vietnam-coffee-growth&usg=AOvVaw2PW6yhIq6_XmLoYN8VY-Qm&opi=89978449 (accessed on 11 April 2017).

- Strong, C. The problems of translating fair trade principles into consumer purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 1997, 15, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer–do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minten, B.; Dereje, M.; Engeda, E.; Tamru, S. Who benefits from the rapidly increasing Voluntary Sustainability Standards? Evidence from Fairtrade and Organic certified coffee in Ethiopia. Gates Open Res. 2019, 3, 1118. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, E.C. Innovativeness, novelty seeking, and consumer creativity. J. Consum. Res. 1980, 7, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.G.; McTavish, R. Segmenting industrial markets by buyer sophistication. Eur. J. Mark. 1983, 17, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, P.A.; Bradford, J.L. Reflections on consumer sophistication and its impact on ethical business practice. J. Consum. Aff. 1996, 30, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Understanding individuals’ environmentally significant behavior. Envtl. L. Rep. News Anal. 2005, 35, 10785. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.H.; Park, Y.B. The present condition and strategy of the coffee market in Korea foodservice industry. In Proceedings of the Culinary Society of Korean Academy Conference, Culinary Society of Korean Academy, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 17–19 May 2006; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.K.; Lee, W.S.; Moon, J.H. Effect of DINESERVE on willingness to pay premium and revisit intention: Case of Starbucks. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 29, 263–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, H.C. The Effect of Coffee Shop Selection Attributes on the Choice of Brand: Using a Multinomial Logit Model. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2020, 95, 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S.; Shim, J.H. The effects of service qualities on customer satisfaction and behavioral intention in coffee shops. J. Ind. Distrib. Bus. 2017, 8, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.Y.; Kim, J.Y. A relationships among choice attributes, emotion, trust and long-term orientation associated with coffee-drinking. Food Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 12, 217–299. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, H.S.; Oh, S.K.; Yoon, H.H. The study on the influence of selection attributes for coffee shop on revisit intention: Based on customers of twenties and thirties. J. Hosp. Tour 2016, 25, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wiryadiputra, S.; Tran, L.K. Indonesia and vietnam. In Plant-Parasitic Nematodes of Coffee; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2008; pp. 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, A. Partnering for sustainability: Business–NGO alliances in the coffee industry. Dev. Pract. 2005, 15, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridell, G. Fair trade slippages and Vietnam gaps: The ideological fantasies of fair trade coffee. Third World Q. 2014, 35, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.Q.; Hoang, V.N.; Wilson, C.; Nguyen, T.T. Which farming systems are efficient for Vietnamese coffee farmers? Econ. Anal. Policy 2017, 56, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci, D.; Lewin, B.; Swinkels, R.; Varangis, P. Socialist Republic of Vietnam Coffee Sector Report. 2004. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=996116 (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Bird, K.; Hughes, D.R. Ethical consumerism: The case of “Fairly–Traded” coffee. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 1997, 6, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, C. Features contributing to the growth of ethical consumerism-a preliminary investigation. Mark. Intell. Plan. 1996, 14, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.M. Fair Trade: Reform and Realities in the International Trading System; Zed Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hindsley, P.; McEvoy, D.M.; Morgan, O.A. Consumer demand for ethical products and the role of cultural worldviews: The case of direct-trade coffee. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 177, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.H. Factors affecting consumer attitude towards purchasing fair trade goods. J. Int. Trade Commer. 2014, 10, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M. The Study of the Meaning of Practical Participation in Global Affairs and its Direction of Education: The Case of Ethical Consumer Participation in Fair Trade. J. Korean Assoc. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2013, 21, 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Lotade, J. Do fair trade and eco-labels in coffee wake up the consumer conscience? Ecol. Econ. 2005, 53, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; MacDonnell, R.; Ellard, J.H. Belief in a just world: Consumer intentions and behaviors toward ethical products. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FLO (Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International). Power in Partnership. 2016. Available online: https://annualreport15-16.fairtrade.net/en/power-in-partnership/ (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Jeong, S.M.; Shin, H.S. A Study on the Willingness-to-Pay the Price Premiums for Fair Trade Coffee in Korean Market. Soc. Enterp. Stud. 2019, 12, 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- FLO (Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International). Monitoring Scope and Benefits of Fair Trade. 2017. Available online: https://www.fairtrade.net/fileadmin/user_upload/content/FairtradeMonitoringReport_9thEdition_lores.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior, In Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Han, H. Building value co-creation with social media marketing, brand trust, and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Safeer, A.A.; Majeed, A. Role of social media marketing activities in China’s e-commerce industry: A stimulus organism response theory context. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 941058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Ajzen, I. Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. J. Res. Personal. 1991, 25, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. The Psychology of Moral Development Vol. II Essays on Moral Development the Nature and Validity of Moral Stages; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Manstead, A.S.R. The role of moral norm in the attitude–behavior relation. In Attitudes, Behavior, and Social Context; Terry, D.J., Hogg, M.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.L.; Lynch, J.G., Jr. Prior knowledge and complacency in new product learning. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, D.Y. A comparison of different approaches to segment information search behaviour of spring break travellers in the USA: Experience, knowledge, involvement and specialisation concept. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.J.; Gim, W.S. Effects of Linguistic Category Cue on Differential Perception of New Digital Convergence Products. Korean J. Consum. Advert. Psychol. 2010, 11, 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Antil, J.H. Conceptualization and operationalization of involvement. Adv. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacciopo, J.T.; Goldman, R. Personal Involvement as a Determinant of Argument-Based Persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. 1981, 41, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, M.; Cantril, H. The Psychology of Ego-Involvements: Social Attitudes and Identifications; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the Involvement Construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, H.E. The Impact of Television Advertising Learning without Involvement. Public Opin. Q. 1965, 29, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A. Involvement: A potentially important mediator of consumer behavior. In Advances in Consumer Research 6; Wilkie, W.L., Ed.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1979; pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hye Ri, S.; Mi, K.Y.; June, Y.S. Effects of Storytelling Technique and Product Involvement on Advertisement Attitude, Brand Attitude and Purchasing Intention. J. Cult. Ind. 2014, 14, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Understanding household garbage reduction behavior: A test of an integrated model. J. Public Policy Mark. 1995, 14, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt brace Jovanovich College Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. 2002. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=0574b20bd58130dd5a961f1a2db10fd1fcbae95d (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Morin, A.J.; Schmidt, P. Gender differences in psychosocial determinants of university students’ intentions to buy fair trade products. J. Consum. Policy 2014, 37, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. The impacts of perceived moral obligation and sustainability self-identity on sustainability development: A theory of planned behavior purchase intention model of sustainability-labeled coffee and the moderating effect of climate change skepticism. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2404–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.; Grover, H.; Vedlitz, A. Examining the willingness of Americans to alter behavior to mitigate climate change. Clim. Policy 2012, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldad, A.; Hegner, S. Determinants of fair trade product purchase intention of Dutch consumers according to the extended theory of planned behaviour. J. Consum. Policy 2018, 41, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.I.; Stoel, L. The effect of social norms and product knowledge on purchase of organic cotton and fair-trade apparel. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2016, 7, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.S.; Ooi, H.Y.; Goh, Y.N. A moral extension of the theory of planned behavior to predict consumers’ purchase intention for energy-efficient household appliances in Malaysia. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M.; Kazeminia, A.; Ghasemi, V. Intention to visit and willingness to pay premium for ecotourism: The impact of attitude, materialism, and motivation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 4. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2022. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.; Lee, S.; Yoon, H.; Kim, C. Linking creating shared value to customer behaviors in the food service context. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usakli, A.; Kucukergin, K.G. Using partial least squares structural equation modeling in hospitality and tourism: Do researchers follow practical guidelines? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3462–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H. Partial least squares. In Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 6, pp. 581–591. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Rigdon, E.E.; Straub, D. Editor’s comments: An update and extension to SEM guidelines for administrative and social science research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, N.F.; Cepeda-Carrión, G.; Roldán Salgueiro, J.L.; Ringle, C.M. European management research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On Evaluation of Structural Equation Model. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Pringer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Geisser, S. A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validation and multinomial prediction. Biometrika 1974, 61, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; de los Salmones, M.D.M.G. Information and knowledge as antecedents of consumer attitudes and intentions to buy and recommend Fair-Trade products. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2018, 30, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelsmacker, P.D.; Janssens, W. A model for fair trade buying behaviour: The role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross National Income per Capita 2022, Atlas method and PPP. World Development Indicators Database, World Bank, 1 July 2023. Available online: https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/GNIPC.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Raynolds, L.T.; Greenfield, N. Fair trade: Movement and markets. In Handbook of Research on Fair Trade; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Havemann, T.; Nair, S.; Cassou, E.; Jaffee, S. Coffee in Dak Lak, Vietnam. In Steps Toward Green: Policy Responses to the Environmental Footprint of Commodity Agriculture in East and Southeast Asia; EcoAgriculture Partners and the World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Factor Loading | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFC | I feel morally obliged to buy fair trade coffee. | 0.932 | 0.948 | 0.918 | 0.859 |

| I feel it as my moral duty to buy fair trade coffee. | 0.934 | ||||

| I feel that I have an ethical obligation to reduce consumption of unfair trade coffee. | 0.913 | ||||

| KFC | I know a lot about fair trade coffee. | 0.930 | 0.950 | 0.930 | 0.826 |

| I feel knowledgeable about fair trade coffee | .0.914 | ||||

| Among my circle of friends, I’m one of the “experts” on fair trade coffee. | 0.874 | ||||

| Compared to most other people, I know more about fair trade coffee. | 0.917 | ||||

| IFC | I like to learn about fair trade coffee. | 0.905 | 0.924 | 0.877 | 0.803 |

| I concentrate on the fair trade coffee. | 0.916 | ||||

| I want to know more about fair trade coffee | 0.867 | ||||

| ATT | Purchasing fair trade coffee is beneficial. | 0.896 | 0.931 | 0.901 | |

| Purchasing fair trade coffee is good. | 0.888 | 0.771 | |||

| Purchasing fair trade coffee is wise. | 0.868 | ||||

| Purchasing fair trade coffee is enjoyable. | 0.860 | ||||

| SN | Most people who are important to me (friends and families) think that I should purchase fair trade coffee. | 0.907 | 0.919 | 0.868 | |

| I believe people around me want me to purchase fair trade coffee. | 0.913 | ||||

| Most people who are important to me (friends and families) have purchased fair trade coffee before. | 0.848 | 0.792 | |||

| PBC | I am confident that I would use fair trade coffee even if another person advised me to use non-fair trade coffee. | 0.849 | 0.922 | 0.895 | |

| I am sure that I would be able to make a difference by using fair trade coffee. | 0.850 | ||||

| Using fair trade coffee is entirely within my control. | 0.760 | ||||

| I am confident that I would use fair trade coffee in future. | 0.882 | 0.705 | |||

| I have the resources, knowledge, and ability to use fair trade coffee. | 0.852 | ||||

| WPM | I am willing to pay a premium fee for fair trade coffee. | 0.939 | 0.957 | 0.932 | |

| I will pay more for the fair trade coffee product. | 0.927 | ||||

| I intend to pay a premium fee for fair trade coffee. | 0.949 | ||||

| 0.880 |

| Measure | MFC | KFC | IFC | ATT | SN | PBC | WPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell–Larcker criterion | |||||||

| MFC | 0.927 * | ||||||

| KFC | 0.524 | 0.909 * | |||||

| IFC | 0.605 | 0.531 | 0.896 * | ||||

| ATT | 0.658 | 0.316 | 0.533 | 0.878 * | |||

| SN | 0.619 | 0.605 | 0.564 | 0.537 | 0.890 * | ||

| PBC | 0.750 | 0.493 | 0.646 | 0.728 | 0.655 | 0.839 * | |

| WPM | 0.660 | 0.433 | 0.598 | 0.686 | 0.618 | 0.776 | 0.938 * |

| Heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio ** | |||||||

| MFC | |||||||

| KFC | 0.563 | ||||||

| IFC | 0.674 | 0.586 | |||||

| ATT | 0.721 | 0.335 | 0.595 | ||||

| SN | 0.693 | 0.674 | 0.645 | 0.606 | |||

| PBC | 0.822 | 0.527 | 0.725 | 0.812 | 0.735 | ||

| WPM | 0.714 | 0.461 | 0.660 | 0.746 | 0.687 | 0.846 | |

| Mean | 3.096 | 2.443 | 3.040 | 3.481 | 2.763 | 3.265 | 3.175 |

| SD a | 1.009 | 1.081 | 0.998 | 0.934 | 1.007 | 0.862 | 1.045 |

| AVE | 0.859 | 0.826 | 0.803 | 0.771 | 0.792 | 0.705 | 0.880 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficient | t-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | MFC → ATT | 0.566 | 12.277 *** | Supported |

| H1b | MFC → SN | 0.332 | 6.711 *** | Supported |

| H1c | MFC → PBC | 0.549 | 13.072 *** | Supported |

| H2a | KFC → ATT | −0.113 | 2.504 * | Not Supported |

| H2b | KFC → SN | 0.332 | 6.761 *** | Supported |

| H2c | KFC → PBC | 0.053 | 1.412 | Not Supported |

| H3a | IFC → ATT | 0.250 | 4.625 *** | Supported |

| H3b | IFC → SN | 0.187 | 3.548 *** | Supported |

| H3c | IFC → PBC | 0.286 | 6.631 *** | Supported |

| H4 | ATT → WPM | 0.235 | 4.294 *** | Supported |

| H5 | SN → WPM | 0.167 | 3.743 *** | Supported |

| H6 | PBC → WPM | 0.496 | 8.507 *** | Supported |

| R2 | ATT = 47.0% | SN = 51.2% | PBC = 62.3% | WPM = 64.9% |

| Q2 | ATT = 0.459 | SN = 0.501 | PBC = 0.616 | WPM = 0.490 |

| H7 | Path | Korea (N = 286) | Vietnam (N = 191) | Kor-Vie p-Value * | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path Co. | t-Value | Path Co. | t-Value | ||||

| H71a | MFC → ATT | 0.551 | 9.843 | 0.588 | 8.160 | 0.341 | Not supported |

| H71b | MFC → SN | 0.395 | 5.937 | 0.301 | 4.232 | 0.166 | Not supported |

| H71c | MFC → PBC | 0.557 | 10.756 | 0.570 | 8.001 | 0.432 | Not supported |

| H72a | KFC → ATT | 0.015 | 0.263 | −0.142 | 2.183 | 0.037 * | Supported |

| H72b | KFC → SN | 0.257 | 3.446 | 0.275 | 4.386 | 0.431 | Not supported |

| H72c | KFC → PBC | 0.074 | 1.472 | −0.018 | 0.303 | 0.118 | Not supported |

| H73a | IFC → ATT | 0.176 | 2.505 | 0.358 | 4.384 | 0.045 * | Supported |

| H73b | IFC → SN | 0.070 | 1.047 | 0.382 | 4.599 | 0.002 ** | Supported |

| H73c | IFC → PBC | 0.229 | 4.119 | 0.367 | 5.731 | 0.051 | Not supported |

| H74 | ATT → WPM | 0.168 | 2.673 | 0.392 | 3.922 | 0.030 * | Supported |

| H75 | SN → WPM | 0.103 | 2.024 | 0.233 | 2.861 | 0.089 | Not supported |

| H76 | PBC → WPM | 0.588 | 9.148 | 0.309 | 3.515 | 0.007 ** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Kim, C.-S.; Jo, M. Cross-Country Analysis of Willingness to Pay More for Fair Trade Coffee: Exploring the Moderating Effect between South Korea and Vietnam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316440

Kim J, Kim C-S, Jo M. Cross-Country Analysis of Willingness to Pay More for Fair Trade Coffee: Exploring the Moderating Effect between South Korea and Vietnam. Sustainability. 2023; 15(23):16440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316440

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jisong, Chang-Sik Kim, and Mina Jo. 2023. "Cross-Country Analysis of Willingness to Pay More for Fair Trade Coffee: Exploring the Moderating Effect between South Korea and Vietnam" Sustainability 15, no. 23: 16440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316440

APA StyleKim, J., Kim, C.-S., & Jo, M. (2023). Cross-Country Analysis of Willingness to Pay More for Fair Trade Coffee: Exploring the Moderating Effect between South Korea and Vietnam. Sustainability, 15(23), 16440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316440