Abstract

Customer mistreatment may be an unavoidable issue for the hospitality industry. Based on the Pressure–State–Response (PSR) framework, this study investigates the process of employees’ pressure, state, and responses to customer mistreatment with the moderation of mindfulness. By using structure modeling equation techniques, we find that employees with high levels of mindfulness can mitigate the impact of customer mistreatment on emotional exhaustion; however, this study unexpectedly found that mindfulness can enhance the impact of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention. This study concludes that instead of conflicting with customers, resulting in their emotional exhaustion, these employees with mindfulness may deal with customer emotions, avoiding the immediate negative impact of customer mistreatment, which is beneficial for hospitality enterprises, particularly given the present state of competition in the industry. Even so, we find that these employees with high-level mindfulness may recognize reality rather than become confused in such circumstances and may choose to leave to find a new job. As such, there is still room for future research into ways to cope with customer mistreatment without increasing the turnover intention of such employees.

1. Introduction

Customer mistreatment is a reflection of poor customer behaviors [1], which include speaking loudly, verbal abuse, making unfair demands, skipping a queue, and other disrespectful behaviors [2]. Employees who experience customer mistreatment may experience emotional distress [3], emotional exhaustion [4], poor physical health [5], poor job performance [6], and absenteeism [7]. Since employee turnover has received increased attention in the hotel industry [8], we propose that if employees are frequently mistreated by customers, turnover intention and work withdrawal may eventually increase [9]. For example, a customer at a busy hotel restaurant becomes irate due to a delayed order. They raise their voice and make unreasonable demands, causing distress to the server (hospitality employee). This public conflict not only disrupts the dining experience but also affects the server’s emotional well-being and overall job performance, potentially contributing to high turnover rates in the hospitality industry. As a result, the study of negative customer–employee interactions is crucial for the hospitality industry due to their increasing prevalence and negative impacts on employees, as described above, highlighting the need to investigate this issue and even provide solutions for hospitality businesses.

Previous research has found that several internal factors, including organizational factors [8,10], managerial factors [11], and individual personal factors [12], influence employee turnover intention. We argue that external factors play an important role in influencing employee turnover [9]. However, the effects of external factors (e.g., customer mistreatment) on employee turnover intention appear to be understudied.

Customer mistreatment, a type of poor treatment from customers, is regarded as an external source that influences employee emotion, potentially leading to work withdrawal behavior and a greater turnover of employees [9]. Thus, we argue that looking for ways to mitigate the adverse effects of customer mistreatment is worthwhile because customer mistreatment interfering with employee performance is a critical issue for the hotel industry. Mindfulness meditation practices are deliberate acts of attention regulation through the observation of thoughts, emotions, and body states that can be used as adjunctive treatments for anxiety disorders [13]. Previous research has shown that mindfulness can help individuals reduce emotional exhaustion [14,15], improve their quality of life [16], and maintain good habits [17]. Furthermore, mindfulness is gaining traction in the hospitality industry; for example, some hotels provide mindfulness training/advice to both employees and customers [18,19]. As a result, we seek to explore the process of employees’ pressure, state, and response to customer mistreatment while examining the moderating effect of mindfulness and validating its way of mitigating the link between customer mistreatment and employee anxiety.

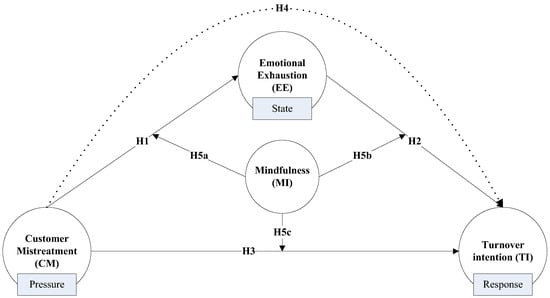

Therefore, we used the PSR framework—pressure (customer mistreatment), state (employee states affected by customer mistreatment), and response (employee performance or other reactions)—with the moderating effect of mindfulness for further analysis. We believe that this study may not only broaden the theory of the PSR model but also prompt employees to utilize mindfulness to alleviate their anxiety; this may shed light on how to deal with dilemmas with a gentle attitude and improve the actions of employees, thereby improving the industry.

Based on the aforementioned concerns, this study aimed to fill gaps in the relevant literature through two key objectives: Firstly, customer mistreatment [9] can negatively impact employees’ emotions, resulting in emotional exhaustion [1] and influencing turnover intention [20,21]. We proposed that emotional exhaustion may play a mediating role between customer mistreatment and employees’ intentions to find new work. Secondly, we wanted to see if mindfulness can moderate the effect of either customer mistreatment or emotional exhaustion on turnover intention, potentially helping employees deal with customer mistreatment. Thus, this study may explain how to connect several factors (e.g., customer mistreatment as a pressure factor, emotional exhaustion as a state factor, turnover intention as a response factor, and mindfulness as a moderating factor) by utilizing the PSR framework.

Additionally, customer mistreatment may be an unavoidable issue for the hospitality industry. Thus, learning new ways to deal with customer mistreatment while maintaining employee performance is critical to the industry’s success.

We argue that this study may add to the existing body of knowledge. First, this study not only addresses the critical need to manage the influences of customer mistreatment in the hospitality industry but also highlights the previously overlooked issue of employee emotional exhaustion as a mediator between customer mistreatment and employee turnover intention, both of which are crucial but rarely addressed in hospitality research. Second, in contrast to prior studies that have explored factors such as global self-esteem and age [6], following the insights of Garcia et al. (2019) [22], our research introduced mindfulness as a moderator and treatment for employee anxiety related to customer mistreatment. Given the prevalence of consumer mistreatment in the hospitality industry, our approach addresses the pressing need to develop novel strategies to preserve employee performance and ensure the industry’s success. Third, based on the use of mindfulness as a treatment for anxiety disorders [23], we found that mindfulness could be used to avoid the immediate negative impact of customer–employee conflicts by mitigating the effect of customer mistreatment on emotional exhaustion, indicating that employees with high levels of mindfulness may be advantageous to hospitality enterprises, especially given the industry’s current competitiveness. Fourth, unexpectedly, we found that mindfulness increases the effect of emotional exhaustion on the of employees intention to leave. We infer that these employees may identify with reality rather than becoming confused at work, thereby deciding to resign or find a new position. Consequently, instead of using other factors that have been shown to influence employee turnover intention in previous studies [14,24], we show that customer mistreatment is a significant factor influencing turnover intention and that mindfulness may not mitigate but rather enhance the impact of employees’ negative emotions on their intention to leave, both of which are notions that appear to be understudied.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Customer Mistreatment

Customers and employees frequently interact with one another. However, in the service industry, the frequent occurrence of customer maltreatment towards employees (e.g., speaking loudly, verbal abuse, unfair demands, jumping a queue, and ill-mannered behaviors) remains a source of concern. Furthermore, as one of the key factors influencing employee emotions, customer mistreatment has numerous side effects on employees [4], frequently resulting in strong emotional reactions among employees [25]. Moreover, previous research has shown that customer mistreatment hurts employees’ health [26] and increases their emotional exhaustion [1].

Previous studies have aimed to address the behavioral impact of employees’ unpleasant feelings produced by customer mistreatment. According to Huang et al. (2019) [27], employee sabotage may be a response to customer maltreatment, although Baranik et al. (2017) [1] argue that cognitive rumination may attenuate customer mistreatment and reduce employee sabotage. Social sharing, such as talking to coworkers, is also a popular response to customer mistreatment [4]. Customer mistreatment’s consequences on employees’ jobs and careers have also been studied since customer mistreatment can change employees’ feelings and behavior. For example, relevant research has shown that when customers mistreat hospitality employees, their service performance suffers [28]; prior research has also shown that customer mistreatment negatively impacts restaurant personnel’s service performance [22], lowers service performance among hospitality employees such as tour guides and frontline staff [29], and, even worse, increases employee absenteeism [30].

Employees are not only harmed when customers are mistreating them, but the consequences are likely to last a long time. According to Shi and Wang (2022) [4], negative emotions caused by customer mistreatment may linger even longer the next day. Many moderating and intervention factors have been proposed gradually because employees’ persistent negative emotions are likely to be detrimental to business. Relevant research suggests that both self-esteem and age [6] alleviate the influence of customer mistreatment on self-confidence threat. Overall, we believe that more research into how to effectively lessen the negative influence of consumer mistreatment is required.

Frequent interactions between customers and service employees in the service industry have given rise to an ongoing issue of unfavorable interactions, including behaviors such as speaking loudly, verbal abuse, making unreasonable demands, queue jumping, and ill-mannered conduct. This persistent problem of customer mistreatment has raised significant concerns within the field [4]. It is worth noting that customer mistreatment not only impacts employees’ emotions but also leads to a multitude of adverse consequences for them [4]. As a critical factor influencing employee emotions, it frequently triggers intense emotional responses among them [25]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that customer mistreatment can have detrimental effects on employees’ health [26] and contribute to heightened emotional exhaustion [1].

Previous research has predominantly concentrated on the behavioral repercussions stemming from employees’ unpleasant emotions derived from customer mistreatment [31,32]. While Huang et al. (2019) [27] argue that employee sabotage can be a response to customer maltreatment, Baranik et al. (2017) [1] suggest that cognitive rumination might mitigate the effects of customer mistreatment and reduce employee sabotage. Social sharing, such as discussing their experiences with coworkers, is another common response to customer mistreatment [4]. Moreover, the consequences of customer mistreatment on employees’ job performance and career prospects have garnered significant research attention, as it fundamentally alters employees’ emotions and behaviors. For instance, pertinent research has demonstrated that when customers mistreat hospitality employees, it negatively affects their service performance [28]. Similarly, customer mistreatment diminishes the service performance of restaurant staff [22] and leads to decreased service quality in hospitality employees such as tour guides and frontline staff [29]. In more severe cases, consumer incivility has been linked to increased employee absenteeism [30].

Importantly, the repercussions of customer mistreatment on employees are not short-lived; they can persist over an extended period. According to Shi and Wang (2022) [4], negative emotions triggered by customer mistreatment may carry over to the following day [33]. Given the potential harm to businesses, numerous moderating and intervention factors have been proposed. Relevant research suggests that both self-esteem and age may alleviate the effect of customer mistreatment on self-confidence threats [6]. As such, it is essential to conduct additional research to mitigate the negative impact of consumer mistreatment on either employees or businesses.

2.2. Pressure–State–Response (PSR) Framework

The Pressure–State–Response (PSR) framework is widely employed in the field of ecology [34]. This framework includes three main components: pressure, state, and response [35]. The PSR framework is also a useful tool for explaining a system’s interaction with external influencing factors by way of capturing the dynamic changes and primary reasoning of events. For example, when people feel pressure from outside factors (P), it may lead to changes in their state (S) that, in turn, lead to a reaction (R) that attempts to relieve the pressure.

Customer mistreatment, as elucidated by Shin et al. (2021) [36], places considerable stress on employees and depletes their resources, thereby subjecting service workers to significant strain [7]. According to the PSR framework, customer mistreatment can be regarded as an external force exerting pressure on employees. Emotional exhaustion, which is characterized as stress-induced depletion [37], represents a state of both physical and mental fatigue resulting from a deficiency in energy and resources.

Within the PSR framework, emotional exhaustion is treated as a state component for employees subjected to the pressure of customer mistreatment. Previous research has explored various response factors, including behavioral and revisit intentions [38,39]. In our study, we have chosen employee turnover intention as the response factor. In Figure 1, we present the conceptual framework that we used to elucidate the connections among these factors. In the framework, customer mistreatment is the pressure factor, emotional exhaustion is the state factor, turnover intention is the response factor, and mindfulness is the moderating factor. After deciding to use this framework for the present study, we proposed several pivotal hypotheses for further investigation.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

Relevant research indicates that interpersonal mistreatment correlates with nurses’ emotional exhaustion [40]; customer mistreatment can deplete employees’ energy and affect their emotions [41], and customer mistreatment contributes to cell phone service workers’ emotional exhaustion [1]. In the service industry, which encompasses sectors such as retail, healthcare, insurance, food services, finance, and higher education, customer mistreatment leads to emotional exhaustion among employees. Moreover, customer mistreatment exacerbates employees’ emotional exhaustion as it subjects them to persistent stressors and depletes their emotional resources [42], leading to heightened emotional fatigue and a reduced capacity to cope with workplace demands [43]. Therefore, according to the PSR framework, external pressure (P) can influence the system’s state (S). We believe that when customers mistreat hospitality workers, their emotions change, resulting in emotional exhaustion. Hence, we proposed H1.

H1.

Customer mistreatment positively affects employees’ emotional exhaustion.

Emotional exhaustion has been found to enhance turnover intention in a variety of fields. Cho et al. (2014) [20] showed that airline staff sometimes resign due to emotional exhaustion. McKenna and Jeske (2020) [44] found that nurses with extreme emotional exhaustion are more likely to leave the profession. Alola et al. (2019) [21] discovered that emotional exhaustion influences hotel employees’ intentions to leave. Thus, emotional exhaustion or burnout may predict turnover intention [45]. Additionally, employees experiencing emotional exhaustion are more likely to contemplate leaving their current job [46] due to decreased job satisfaction and diminished emotional resources, leading to heightened turnover intention [47]. Consequently, according to the PSR framework, the change in a system’s state (S) may trigger a behavior reaction (R). Hence, we inferred that emotional exhaustion may result in turnover intention, leading us to propose H2.

H2.

Employees’ emotional exhaustion increases their turnover intention.

Previous research has shown that customer mistreatment causes employee absenteeism [7], work withdrawal [9], and even turnover intention. Diefendorff et al. (2019) [48] also stated that staff in call center services have a high intention to leave due to being on the receiving end of poor client treatment frequently. Furthermore, customer mistreatment can increase employees’ turnover intention by creating a stressful and hostile work environment [49]. The accumulated emotional toll from mistreatment can lead employees to seek alternative employment opportunities for relief [50]. Hence, based on the above, we proposed H3.

H3.

Customer mistreatment increases employees’ turnover intention.

2.3. The Mediation of Emotional Exhaustion

According to the PSR framework, the state factor (emotional exhaustion) can serve as a link between the pressure factor (customer mistreatment) and the response factor (turnover intention). In addition, emotional exhaustion may mediate the links between customer mistreatment and job satisfaction [48], job demands and instigated workplace incivility [51], and workplace ostracism and interpersonal deviance [52]. Furthermore, employees’ emotional exhaustion may serve as a crucial mediator in the relationship between customer mistreatment and turnover intention. When mistreated by customers, employees often experience heightened emotional exhaustion [53], prompting them to consider leaving their jobs in search of relief from these emotionally draining interactions [54]. As such, we hypothesized that emotional exhaustion may mediate the link between customer mistreatment and employees’ turnover intention by proposing H4.

H4.

Employees’ emotional exhaustion mediates the link between customer mistreatment and employees’ turnover intention.

2.4. The Moderation of Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a deliberate and nonjudgmental focus on the present moment [55]. To regulate attention, mindfulness meditation involves observing thoughts, emotions, and body states [56]. Mindfulness may provide people with a sense of control and a pleasant affective consequence because it involves conscious awareness, non-subjective judgment, and present moment focus [56]. Individuals with high-level mindfulness might recover from negative emotions more quickly due to their ability to recognize reality without becoming confused [57]. Furthermore, relevant research has shown that mindfulness positively affects psychological distress [58], experience [59], and long-term sustainable behavior [57].

Previous research has shown that employee emotional exhaustion may be mitigated by mindfulness [14,42]. People who practice mindfulness may analyze the current situation before making decisions rather than relying on experience [17], and mindfulness may help to moderate the link between environmental influences and one’s emotional state [60]. Additionally, by utilizing mindfulness, employees may develop better emotional regulation skills [17], helping them cope with mistreatment more effectively and reducing the impact of such experiences on their emotional exhaustion [61]. As such, we inferred that employees with high-level mindfulness might be less emotionally exhausted by customer mistreatment, thereby proposing H5a.

H5a.

Mindfulness moderates the link between customer mistreatment and employees’ emotional exhaustion.

According to previous studies, tourists who practice mindfulness are more likely to modify their behavior because they may be aware of how their actions affect others [17]; mindfulness can stimulate an individual’s self-regulating activities by reducing stress, likely resulting in fewer defensive responses [62], and mindfulness has been shown to be associated with self-control but not impulsive actions such as physical and verbal aggression [63]. Additionally, practicing mindfulness can enhance employees’ resilience and coping mechanisms, making them less likely to consider leaving their jobs when experiencing emotional exhaustion [64]. Additionally, employees who practice mindfulness can better handle the emotional impact of mistreatment, lowering their intention to leave as they become more resilient and adaptable in facing customer mistreatment [65]. As a result, we developed hypotheses H5b and H5c because we expected the relationships shown below to be attenuated for individuals with higher levels of mindfulness.

H5b.

Mindfulness moderates the link between employees’ emotional exhaustion and their turnover intention.

H5c.

Mindfulness moderates the link between customer mistreatment and employees’ turnover intention.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Measurement Items

The scale of measuring items for diverse constructs was obtained from validated and reliable multi-item scales. Customer mistreatment was assessed using eight items proposed by Park and Kim (2020) [28], emotional exhaustion was gauged using the six items discussed by Aryee et al. (2015) [66], employees’ turnover intention was assessed using the four items discussed by Haldorai et al. (2019) [67], and mindfulness was assessed by using the twelve items recommended by Hwang and Lee (2019) [3]. These items were evaluated utilizing a five-point Likert scale. In addition, we adapted these items so that they suited the context of our study.

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

Concerning the severe impact of COVID-19, questionnaires were issued via Wenjuanxing (https://www.wx.cn/, accessed on 5 March 2021), one of China’s largest and most professional online survey platforms [68]. In addition, with the aid of tourism bureaus in Quanzhou, Xiamen, and Zhangzhou, people in charge of hospitality enterprises helped us fill out our questionnaire by asking the bureaus to send the questionnaire link to their personnel. Sample responses were obtained via conducting an online survey between 1 March and 30 March 2021. After eliminating responses due to repeated IP filling, regular filling, short filling time, and contradictory questionnaires, we then obtained 427 valid samples (Table 1) for our investigation. Specifically, one questionnaire from the same IP address was included in the study, and those with identical responses and surveys that had been completed outside of a specific time frame (i.e., the time taken to complete the survey should have been between three and thirty minutes) were considered invalid.

Table 1.

The socio-demographic profiles of the respondents.

3.3. Methodologies and Software Utilized for Data Analysis

Subsequently, SEM, Process 3.4, and Amos 24.0 were used to analyze data and test hypotheses. After confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), we checked the measurement model to see if the constructs and items were valid and reliable. Following that, Process 3.4 helped us investigate the structural model and identify the causal linkages between constructs, and the SPSS process macro model 59 was used to examine the moderating effects [69].

Table 1 shows that there were more male respondents (59.95%) than female respondents (40.05%) and that most respondents (91.34%) were younger than 35 years old; 38.88% of our respondents were college or university graduates at the time of completing the survey, and 44.96% of them earned CNY 6001–9000 at the time of completing the survey. In addition, Table 1 shows that these employees worked in different sub-industries of the hospitality and tourism industry, including the catering industry (41.45%), hotel industry (3.75%), travel agency industry (4.45%), scenic area industry (4.92%), MICE industry (4.5%), aircraft industry (2.34%), express industry (7.25%), and others (26.93%). Regarding their work experience, 20.37% of them had less than six months, 30.91% of them had worked for 6-12 months, 28.10% of them had 1-3 years worth of work experience, and the rest of them (20.61%) had work experience spanning over 3 years.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Validation

Based on confirmatory factor analysis in Table 2, this study excluded items CM1, EE3, TI3, and MI3-9 because their standardized factor loadings were less than 0.5. Cronbach’s Alpha showed that each variable’s Alpha was greater than 0.7, indicating sample reliability. We used CFA to validate our results and prove that the SEM model fit indices met acceptable standards (Hu and Bentler, 1999) [70], which they did, as shown by the values of χ2/df = 1.924, RMSEA = 0.047 < 0.08, SRMR = 0.047 < 0.08, CFI = 0.951 > 0.9, and TLI = 0.943 > 0.9. Furthermore, we examined whether our results contained common method bias as defined by Podsakoff et al. (2003) [71]. All items were subjected to exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The variance interpretation rate of this study’s initial factor was 26.62 %, representing the common method deviation without biasing our revealed results.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

The measuring model’s convergent validity was also examined. Two tests were used to determine convergent validity. The first is that the standardized factor loading of each item has to be larger than 0.5, and the second is that each construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) has to be greater than 0.5 [72]. Table 3 displays each item’s AVE and normalized factor loading. Table 2 also shows that the AVE values are all greater than 0.5 and the CR values are all larger than 0.7. Variable discriminative validity was achieved because the AVE is greater than the squared correlations of these constructs. Thus, our samples are consistent and valid.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.2.1. Testing Direct Effects

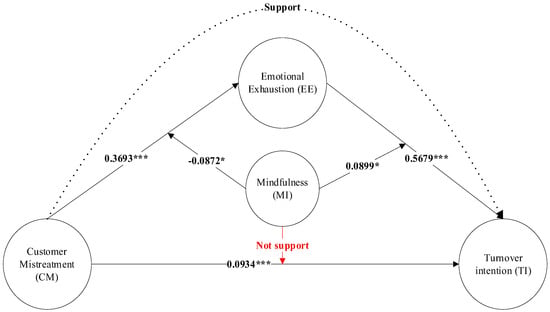

Following the testing process of previous studies, we test the moderated mediation effect after examining the direct effect [73]. In Table 4, we present the following direct impacts using SPSS for regression analysis [74]. Table 3 shows that customer mistreatment has a significant positive effect on emotional exhaustion (β = 0.3693, p < 0.001), supporting H1; emotional exhaustion has a significant positive effect on turnover intention (β = 0.5731, p < 0.001), supporting H2, and customer mistreatment has a significant negative effect on turnover intention (β = 0.0904, p < 0.05), supporting H3.

Table 4.

Hypotheses testing.

4.2.2. Testing the Mediating Effect

This study bootstrapped 5000 samples using the PROCESS macro plugin specialized for mediation and moderation analysis. Table 5 shows that in addition to the significant direct effect of customer mistreatment on turnover intention (direct effect = 0.0947, boot SE = 0.0412, BCI [0.0221, 0.0136]), the indirect effect of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention is significant (indirect effect = 0.2156, boot SE = 0.0329, BCI [0.1535, 0.2824]), supporting H4. This indirect effect reveals that emotional exhaustion mediates the link between customer mistreatment and turnover intention. Customer mistreatment significantly affects turnover intention (total effect = 0.3102, boot SE = 0.0461, BCI [0.0000, 0.2196]).

Table 5.

Testing the mediating effect.

4.2.3. Testing the Moderating Effects

Table 4 demonstrates that attempting to alleviate the effects of customer mistreatment via mindfulness can negatively significantly affect emotional exhaustion (β = −0.0872, p < 0.05) but insignificantly affect turnover intention (β = −0.0633, p > 0.05). These findings indicate that H5a is supported but H5c is not supported. In other words, mindfulness does mitigate the impact of customer mistreatment on emotional exhaustion but does not affect the impact of customer mistreatment on turnover intention. However, attempts to mitigate emotional exhaustion via mindfulness positively significantly affected turnover intention (β = 0.0899, p < 0.05), supporting H5b.

Our results show that, for hospitality employees with high-level mindfulness, the influence of customer mistreatment on emotional exhaustion can be alleviated, and the impact of customer mistreatment on employees’ intention to leave may not be significant. We infer that these hospitality employees might gently handle customer mistreatment instead of acting out and engaging in conflict with customers, thereby alleviating customers’ negative emotions and avoiding the immediate negative effects of customer mistreatment, which may benefit hospitality businesses, especially in the industry’s present competitive environment.

However, we unexpectedly found that the impact of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention can be exaggerated for hospitality employees with high-level mindfulness. We deduce that even though mindfulness is likely to result in one disengaging from negative appraisal and emotion [14], these employees may identify reality instead of becoming confused in such surroundings, so they may alleviate their negative emotions [57] by leaving or finding a new job [75,76].

Figure 2 shows the results of whether our proposed hypotheses are supported.

Figure 2.

Results concerning the hypotheses. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between customer mistreatment, hospitality employees’ turnover intention, and the moderating role of mindfulness. Firstly, our research confirms that customer mistreatment significantly influences employees’ turnover intention, which is primarily mediated by emotional exhaustion [28,77]. This underscores the importance of external factors like consumer behavior in understanding turnover intention, as previous studies have mostly focused on internal or personal factors [42,78].

Furthermore, our findings reveal the crucial role of mindfulness in mitigating the impact of customer mistreatment on emotional exhaustion. Employees with high mindfulness levels can effectively regulate their emotions when dealing with mistreatment from customers, thus reducing emotional exhaustion [53,61].

Interestingly, our study uncovers an unexpected result: mindfulness appears to enhance the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention. Employees with high levels of mindfulness might be more attuned to recognizing when their current situation is untenable, leading them to actively seek alternative employment opportunities [17]. This surprising finding highlights the need for further investigation into strategies to address customer mistreatment without inadvertently increasing turnover intention among highly mindful employees. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between customer mistreatment, employee well-being, and turnover intention, emphasizing the importance of mindfulness as a valuable coping mechanism in the hospitality industry.

6. Concluding Remarks

6.1. Conclusions

Since customer mistreatment, one of the main sources of work stress [79], has received more attention in the service industry, in this study, our primary objective was to investigate the influence of customer mistreatment on hospitality employees’ turnover intention through utilizing emotional exhaustion as a mediator and mindfulness as a moderator. These variables have received limited attention in the literature, and we aimed to shed light on their significance in the context of the service industry, making several noteworthy contributions to the existing literature.

First, our research departed from the conventional focus on internal organizational and personal factors influencing turnover intention. Instead, we discovered that customer mistreatment significantly affects employees’ turnover intention, marking a critical departure from previous studies that have primarily examined internal factors [48]. This novel finding underscores the importance of considering external factors like customer behavior in understanding turnover intention, thereby enriching the literature.

Second, in alignment with previous research [1,53], our study validated the impact of customer mistreatment on employees’ emotional exhaustion. Moreover, we introduced emotional exhaustion as a mediating factor between customer mistreatment and turnover intention. By applying the PSR framework to our research context, we extended its application beyond the ecology field, highlighting how external pressures such as customer mistreatment can lead to state changes and subsequently influence employee turnover intention. This extension of the PSR framework to other fields represents a noteworthy contribution to the existing literature.

Third, our research revealed that employees with heightened mindfulness can effectively counteract the impact of customer mistreatment on emotional exhaustion. Instead of reacting by engaging in conflict and/or exhibiting signs of emotional distress, these mindful individuals adequately manage customer emotions, thus preventing the immediate negative consequences of mistreatment [1]. This innovative finding offers a fresh approach to addressing customer mistreatment in the hospitality industry, with the potential to greatly benefit businesses in the highly competitive service sector. It highlights the importance of mindfulness as a valuable tool for enhancing both customer service quality and employee well-being.

Fourth and unexpectedly, our study uncovered that mindfulness enhances the impact of emotional exhaustion on employees’ turnover intention. We conclude that these employees may recognize reality instead of being confused at work and leave or find a new job instead of staying at their current place of work. We believe that this finding is related to either the fact that individuals with high-level mindfulness are more likely to disengage from negative appraisal and emotion [14] or that those who practice mindfulness meditation are more able to investigate external possibilities by adapting their behavior [80], such as by applying for new jobs [75]. Thus, mindfulness can aid employees in recognizing reality, quickly moving away from negative emotions, and exploring new options, all of which appear to be understudied and even undisclosed in the relevant literature.

In conclusion, our study contributes significantly to the literature by delving into the dynamics of customer mistreatment, emotional exhaustion, mindfulness, and turnover intention in the context of the service industry. These findings offer valuable insights into employee well-being and retention, emphasizing the importance of considering external factors and mindfulness interventions to enhance employee resilience and retention in a highly competitive environment.

6.2. Research Implications

6.2.1. Theoretical Implications

We discovered that emotional exhaustion mediates the link between customer mistreatment and employees’ intention to leave and that mindfulness can enhance the influence of emotional exhaustion on employees’ turnover intention. This study not only expanded on other factors affecting employees’ turnover intention but also broadened the application of the PSR framework from ecology to hospitality management.

Our thorough investigation of the adverse influences of customer mistreatment on service industry employees (e.g., emotional exhaustion, employee stress, and decreased service performance) emphasizes the need for the effective management of customer mistreatment at work. Furthermore, this study may contribute to a better understanding of the influence of customer mistreatment on employee anxiety, stress, and coping behavior with the aid of mindfulness by providing valuable insights into the complex interactions between customer mistreatment, emotional exhaustion, and intention to leave and the moderating effect of mindfulness for hospitality enterprises.

While customer mistreatment has been shown to hurt employees in nursing, healthcare, cell phone service workers, and other service industries, we discovered that it also harms hospitality employees, increasing their intention to leave. As consumer mistreatment has become more common in the hospitality industry, we argue that, in addition to applying the PSR framework, addressing customer mistreatment issues from either more theoretical perspectives or based on the theoretical foundations of other fields in future investigations is critical, significantly broadening the scope of this study.

6.2.2. Practical Implications

By applying the PSR framework, we showed that customer mistreatment can affect employees’ turnover intention through emotional exhaustion. Our findings suggest that employees’ emotions can affect the hospitality industry’s growth since emotional exhaustion can boost turnover intention. Since employee emotions affect job performance, life quality, and personal growth [51,54], managers should consider the emotional state of employees who deal with various situations wherein they are forced to interact with consumers. Thus, aside from learning about the mediating role of emotional exhaustion, understanding more processes and even causes (e.g., mediators) would be advantageous for these businesses. Thus, we advise that the relevant parties investigate whether the influence of customer mistreatment on employee intention to leave is caused by other processes.

Furthermore, the influence of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention can be intensified by employees with high-level mindfulness since they are likely to disengage from a negative emotion and/or seek external possibilities like new jobs. However, employees with high levels of mindfulness may alleviate the influence of customer mistreatment on emotional exhaustion, lessening the immediate negative impact of customer mistreatment and helping rather than harming hospitality businesses.

Moreover, managers should assist employees in dealing with customer mistreatment, given the detrimental impact of customer mistreatment on the development of the hospitality industry. Managers, for example, may conduct situational simulations to improve coping skills by allowing employees to act as customers and simulate customer mistreatment [81], hold sharing meetings to teach employees how to release their negative emotions, and invite experienced employees to share their experience in dealing with customer mistreatment. Managers can also use management skills like empathy, listening, and coaching to help their employees manage their emotions.

Finally, because higher-ranking employees may not face customer mistreatment as frequently as guest-facing employees, we propose that if high-ranking employees act as guest-facing employees, enterprises may develop more measures to deal with customer mistreatment, thereby benefiting their business. We assert that the preceding suggestions, viewpoints, and even philosophy are primarily based on the following proverbs: “suffer and grow strong and no pain, no gain” [82].

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study’s limitations are multifaceted. Firstly, the reliance on a cross-sectional approach and internet-based questionnaires in the context of COVID-19 constrains our ability to establish causal relationships and fully grasp the pandemic’s impact. Future research avenues should consider a longitudinal, qualitative design that incorporates in-depth interviews and follow-up studies to comprehensively unravel the intricacies of how customer mistreatment affects hospitality employees over time. Moreover, expanding the study’s scope to encompass a broader spectrum of outcomes (e.g., encompassing physical, psychological, and occupational facets beyond emotional exhaustion and turnover intention) would provide a more holistic perspective. Furthermore, future investigations could focus exclusively on hospitality employees with mindfulness meditation training, allowing for a deeper exploration of the role of mindfulness in mitigating mistreatment’s effects. Lastly, exploring alternative moderators from managerial perspectives could uncover novel strategies to bolster employee well-being and enhance the performance of hospitality enterprises.

As a result, we argue that providing guidelines on how to deal with customer mistreatment with a gentle attitude and mindfulness training for employees is likely to reduce conflict between employees and customers, even if these employees may recognize reality rather than becoming confused in such circumstances, avoid the emotional effects caused by customer mistreatment, and find a new job. Given the hospitality industry’s competitiveness, the aforementioned approach may be beneficial to the hospitality sector by helping to avoid the immediate adverse impact of customer mistreatment. Nonetheless, we believe that there is still room for future researchers to find ways to deal with customer mistreatment without increasing employee turnover intention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y., Y.N., Y.F. and Y.C.; Software, J.Y. and Y.N.; Investigation, J.Y., Y.N., Y.F. and Y.C.; Methodology, J.Y. and Y.N., Writing—original draft, J.Y., Y.N., Y.F. and Y.C.; Writing—review and editing, J.Y., Y.N., Y.F. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research article was supported by the Youth Project of National Social Science Foundation, China (20CGL022), and the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC 112-2410-H-032-047).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first author upon reasonable request at 15980301687@163.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baranik, L.E.; Wang, M.; Gong, Y.; Shi, J. Customer Mistreatment, Employee Health, and Job Performance: Cognitive Rumination and Social Sharing as Mediating Mechanisms. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheer, I.; Carr, N. Social representations of tourists’ deviant behaviours: An analysis of Reddit comments. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Lee, B. Pride, mindfulness, public self-awareness, affective satisfaction, and customer citizenship behaviour among green restaurant customers. Int. J. Hosp. Mgmt. 2019, 83, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wang, X. Daily spillover from home to work: The role of workplace mindfulness and daily customer mistreatment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Mgmt. 2022, 34, 3008–3028. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Liu, S.; Wu, H.; Wu, K.; Pei, J. To avoidance or approach: Unraveling hospitality employees’ job crafting behavior response to daily customer mistreatment. J. Hosp. Tour. Mgmt. 2022, 53, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarnani, R.K.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Bordia, P.; Abbasi, A.A. Age as double-edged sword among victims of customer mistreatment: A self-esteem threat perspective. Hum. Resour. Mgmt. 2019, 58, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraglia, M.; Johns, G. The Social and Relational Dynamics of Absenteeism From Work: A Multilevel Review and Integration. Acad. Mgmt. Ann. 2021, 15, 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, A.; Ma, E.; Lloyd, K.; Reid, S. Organizational ethnic diversity’s influence on hotel employees’ satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention Gender’s moderating role. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 76–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Melhem, S.; Quratulain, S.; Al-Hawari, M.A. Customer incivility and frontline employees’ revenge intentions: Interaction effects of employee empowerment and turnover intentions. J. Hosp. Mktg. Mgmt. 2019, 29, 450–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Ling, Q. Managing internal service quality in hotels: Determinants and implications. Tour. Mgmt. 2021, 86, 104329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ji, Y.; Ni, Y. Does “Nei Juan” affect “Tang Ping” for hotel employees? The moderating effect of effort-reward imbalance. Int. J. Hosp. Mgmt. 2023, 109, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cherian, J.; Han, H. CSR and organizational performance: The role of pro-environmental behavior and personal values. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2022, 30, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Lenka, U. Exploring interventions to curb workplace deviance lessons from Air India. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wong, I.A.; Kim, W.G. Does mindfulness reduce emotional exhaustion? A multilevel analysis of emotional labor among casino employees. Int. J. Hosp. Mgmt. 2017, 64, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panditharathne, P.N.K.W.; Chen, Z. An Integrative Review on the Research Progress of Mindfulness and Its Implications at the Workplace. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Eyoun, K. Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Hosp. Mgmt. 2021, 94, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo-Barrios, M.; Pitt, L. Mindfulness and the challenges of working from home in times of crisis. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Haobin, Y.; Huiyue, Y.; Peng, L.; Fong, L.H.N. The impact of hotel servicescape on customer mindfulness and brand experience: The moderating role of length of stay. J. Hosp. Mktg. Mgmt. 2021, 30, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, S.T.; Li, G. Abusive supervision and emotional labour on a daily basis: The role of employee mindfulness. Tour. Mgmt. 2023, 96, 104719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.-E.; Choi, H.S.C.; Lee, W.J. An Empirical Investigation of the Relationship Between Role Stressors, Emotional Exhaustion and Turnover Intention in the Airline Industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alola, U.V.; Olugbade, O.A.; Avci, T.; Öztüren, A. Customer incivility and employees’ outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tour. Mgmt. Perspect. 2019, 29, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Lu, V.N.; Amarnani, R.K.; Wang, L.; Capezio, A. Attributions of blame for customer mistreatment: Implications for employees’ service performance and customers’ negative word of mouth. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Ferrando, S.; Findler, M.; Stowell, C.; Smart, C.; Haglin, D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2008, 22, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Ni, Y. COVID-19 event strength, psychological safety, and avoidance coping behaviors for employees in the tourism industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Mgmt. 2021, 47, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCance, A.S.; Nye, C.D.; Wang, L.; Jones, K.S.; Chiu, C.-y. Alleviating the Burden of Emotional Labor. J. Manag. 2010, 39, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lu, M.; Huang, X. Customer mistreatment and employee well-being: A daily diary study of recovery mechanisms for frontline restaurant employees in a hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-S.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Bonner, J.M.; Wang, C.S. Why sabotage customers who mistreat you? Activated hostility and subsequent devaluation of targets as a moral disengagement mechanism. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.-J.; Kim, P.B.; Hai, S.; Dong, L. Relax from job, Don’t feel stress! The detrimental effects of job stress and buffering effects of coworker trust on burnout and turnover intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Kim, T.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.K. Testing the stressor–strain–outcome model of customer-related social stressors in predicting emotional exhaustion, customer orientation and service recovery performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.N.; van Niekerk, M.; Orlowski, M. Customer and employee incivility and its causal effects in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lee, L.; Popa, I.; Madera, J.M. Should I leave this industry The role of stress and negative emotions in response to an industry negative work event. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simillidou, A.; Christofi, M.; Glyptis, L.; Papatheodorou, A.; Vrontis, D. Engaging in emotional labour when facing customer mistreatment in hospitality. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey-Cordes, R.; Eilert, M.; Büttgen, M. Eye for an eye? Frontline service employee reactions to customer incivility. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 34, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, A.C.; Dupin, P.; Sanchez, L.E. A pressure–state–response approach to cumulative impact assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemi, M.; Jozi, S.A.; Malmasi, S.; Rezaian, S. Conceptual framework for evaluation of ecotourism carrying capacity for sustainable development of Karkheh protected area, Iran. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.-M.; Hwang, H. Impacts of customer incivility and abusive supervision on employee performance: A comparative study of the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods. Serv. Bus. 2021, 16, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, A.; Mahmood, Z.; Sharif, S.; Ersoy, N.; Ehtiyar, R. Exploring the Associations between Social Support, Perceived Uncertainty, Job Stress, and Emotional Exhaustion during the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Orús, C. Integrating virtual reality devices into the body: Effects of technological embodiment on customer engagement and behavioral intentions toward the destination. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Cheng, Y.; Bi, Y.; Ni, Y. Tourists perceived crowding and destination attractiveness: The moderating effects of perceived risk and experience quality. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-S.; Yoon, H.-H. The Effect of Social Undermining on Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion and Procrastination Behavior in Deluxe Hotels: Moderating Role of Positive Psychological Capital. Sustainability 2022, 14, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.W.; Han, S.-J. The effect of customer incivility on service employees’ customer orientation through double-mediation of surface acting and emotional exhaustion. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2015, 25, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Mai, K.M.; Qiu, F.; Ilies, R.; Tang, P.M. Are you too happy to serve others? When and why positive affect makes customer mistreatment experience feel worse. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2022, 172, 104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepanier, S.; Henderson, R.; Waghray, A. A Health Care System’s Approach to Support Nursing Leaders in Mitigating Burnout Amid a COVID-19 World Pandemic. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2022, 46, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, J.; Jeske, D. Ethical leadership and decision authority effects on nurses’ engagement, exhaustion, and turnover intention. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 77, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentein, K.; Guerrero, S.; Jourdain, G.; Chênevert, D. Investigating occupational disidentification: A resource loss perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 2017, 32, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V.; Allen, D.G. Job embeddedness and voluntary turnover in the face of job insecurity. J. Organ. Behav. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, J.; Doherty, I.; Reede, L.; Mahoney, C.B. Predictors of burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover among CRNAs during COVID-19 surging. AANA J. 2022, 90, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Gabriel, A.S.; Nolan, M.T.; Yang, J. Emotion regulation in the context of customer mistreatment and felt affect: An event-based profile approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, B.; St-Onge, S.; Ali, M. Consumer aggression and frontline employees’ turnover intention: The role of job anxiety, organizational support, and obligation feeling. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Guan, X.; Zhou, L.; Huan, T.-C. Will catering employees’ job dissatisfaction lead to brand sabotage behavior? A study based on conservation of resources and complexity theories. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1882–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, V.-Y.; Pun, P.-Y. The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Job Satisfaction on the Relationship Between Job Demands and Instigated Workplace Incivility. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2017, 54, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, S.; Fatima, T. How Workplace Ostracism Influences Interpersonal Deviance: The Mediating Role of Defensive Silence and Emotional Exhaustion. J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 33, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Xie, J. Does customer mistreatment hinder employees from going the extra mile? The mixed blessing of being conscientious. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.d.J.; Said, H.; Ali, L.; Ali, F.; Chen, X. COVID-19 and unpaid leave: Impacts of psychological contract breach on organizational distrust and turnover intention: Mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, I. Investigating key innovation capabilities fostering visitors’ mindfulness and its consequences in the food exposition environment. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Exploring mindfulness and stories in tourist experiences. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.Y. Mindfulness promotes sustainable tourism: The case of Uluru. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 22, 1526–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.K.; Lee, R.A.; Mills, M.J. Mindfulness at Work: A New Approach to Improving Individual and Organizational Performance. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.M.; Arnold, K.A. The bright and dark sides of employee mindfulness: Leadership style and employee well-being. Stress Health 2020, 36, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Breazeale, M.; Radic, A. Happiness with rural experience: Exploring the role of tourist mindfulness as a moderator. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhou, X.; Ren, J.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Shao, W. A self-regulatory perspective on the link between customer mistreatment and employees’ displaced workplace deviance: The buffering role of mindfulness. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2704–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op den Kamp, E.M.; Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Creating a creative state of mind: Promoting creativity through proactive vitality management and mindfulness. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 72, 743–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, A.M.; Simons, R.M.; Simons, J.S.; Welker, L.E. Prediction of verbal and physical aggression among young adults: A path analysis of alexithymia, impulsivity, and aggression. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, E.; Bayighomog, S.W.; Tanova, C. Workplace bullying, psychological distress, resilience, mindfulness, and emotional exhaustion. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 40, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Jo, W.; Kim, J.S. Can employee workplace mindfulness counteract the indirect effects of customer incivility on proactive service performance through work engagement? A moderated mediation model. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 812–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Sun, L.-Y.; Chen, Z.X.G.; Debrah, Y.A. Abusive Supervision and Contextual Performance: The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion and the Moderating Role of Work Unit Structure. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2015, 4, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Pillai, S.G.; Park, T.; Balasubramanian, K. Factors affecting hotel employees’ attrition and turnover: Application of pull-push-mooring framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Law, R.; Liu, J. Co-creating value with customers A study of mobile hotel bookings in China. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2056–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: A comment. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, I.K.V.; Wong, I.A. The role of relationship quality and loyalty program in tourism shopping: A multilevel investigation. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-J. Sense of calling and career satisfaction of hotel frontline employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 346–365. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, A.; Hommes, M.; Brouwers, A.; Tomic, W. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction course on stress, mindfulness, job self-efficacy and motivation among unemployed people. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2013, 22, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Kang, D.-s. Reducing the Negative Effects of Abusive Supervision: A Step towards Organizational Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 15, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, K.H. From Customer-Related Social Stressors to Emotional Exhaustion: An Application of the Demands–Control Model. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 1068–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-P. Exploring career commitment and turnover intention of high-tech personnel: A socio-cognitive perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 31, 760–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J.; Lanaj, K.; Bono, J.; Campana, K. Daily shifts in regulatory focus: The influence of work events and implications for employee well-being. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 1293–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ni, Y. Staging a comeback? The influencing mechanism of tourist crowding perception on adaptive behavior. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104827. [Google Scholar]

- Sommovigo, V.; Setti, I.; O’ Shea, D.; Argentero, P. Investigating employees’ emotional and cognitive reactions to customer mistreatment: An experimental study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 707–727. [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, M.C.; Lenferink, L.I.M.; Stroebe, M.S.; Boelen, P.A.; Schut, H.A.W. No pain, no gain: Cross-lagged analyses of posttraumatic growth and anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief symptoms after loss. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).