Exploring Motivations and Trust Mechanisms in Knowledge Sharing: The Moderating Role of Social Alienation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- What motivations may positively influence the affect-based trust and technology-based trust under the use of ESM?

- RQ2:

- Do affect-based trust and technology-based trust mediate the relationship between these motivations and knowledge sharing?

- RQ3:

- How does the situation of social alienation effect the relationship between these two dimensions of trust and an employee’s knowledge-sharing behavior in the workplace?

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Social Exchange Theory

2.2. UTAUT Model

2.3. Enterprise Social Media in Knowledge Sharing

2.4. Motivations in Knowledge Sharing

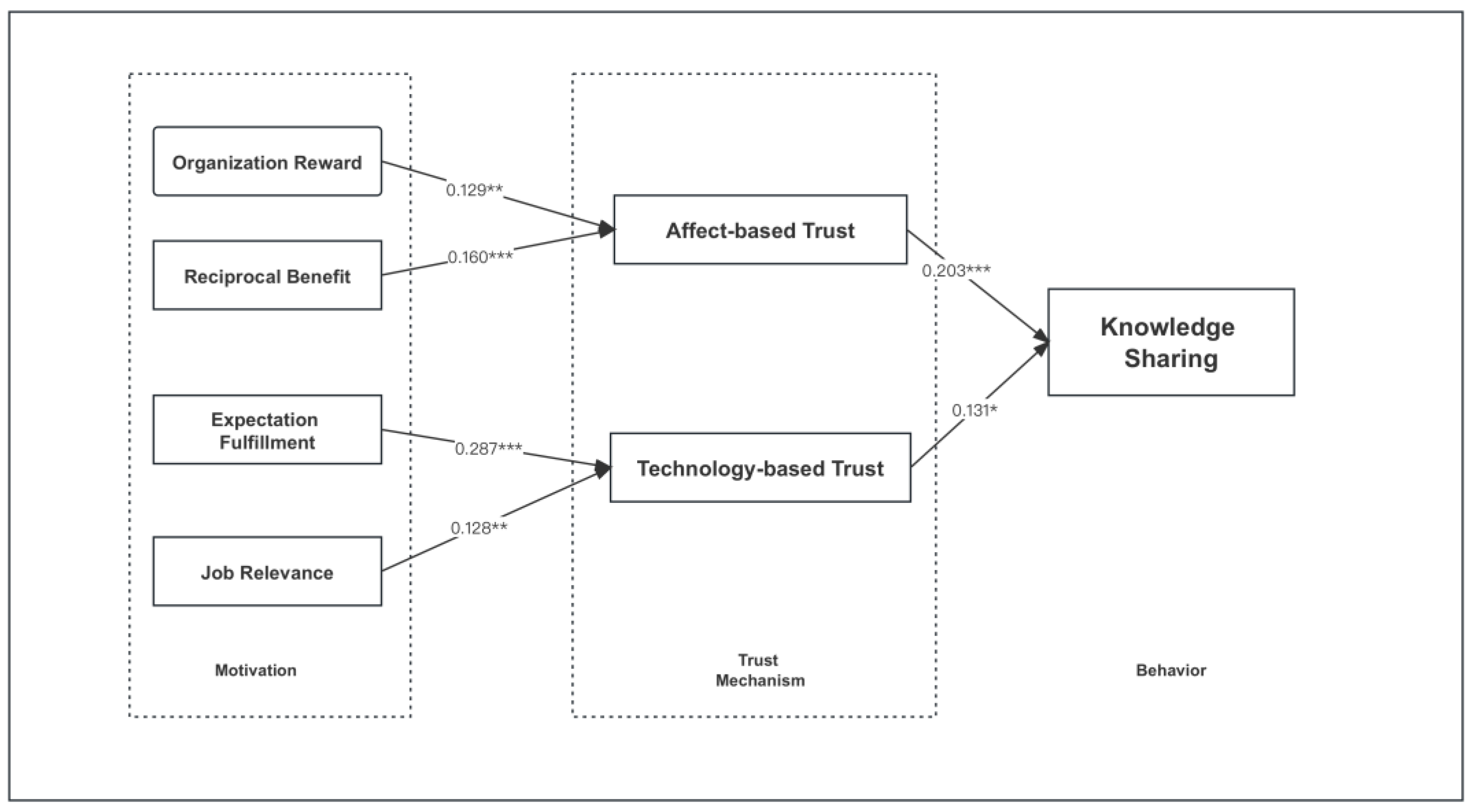

3. Conceptual Model and Hypothesis Design

3.1. Model Development

3.2. Hypothesis Design

3.2.1. Technology-Based Trust, Affect-Based Trust, and Knowledge Sharing

3.2.2. Motivations on Affect-Based Trust and Technology-Based Trust

3.2.3. The Moderation Role of Social Alienation

4. Methodology

4.1. Measurement and Instrument

4.2. Data Collection

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Common Method Bias

5.2. The Measurement Model

5.3. The Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5.4. Indirect Effects Test

5.5. Moderating Effects of Social Alienation

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. General Discussion

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OR | Organization rewards |

| RB | Reciprocal benefits |

| EF | Expectation fulfillment |

| JR | Job relevance |

| SME | Small- and medium-sized enterprise |

| ABT | Affect-based trust |

| TBT | Technology-based trust |

| SA | Social alienation |

| ESM | Enterprise social media |

References

- Than, S.T.; Le, P.B.; Le, T.T. The impacts of high-commitment HRM practices on exploitative and exploratory innovation: The mediating role of knowledge sharing. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2023, 53, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pan, L.; Song, A.; Ma, X.; Yang, J. Research on the strategy of knowledge sharing among logistics enterprises under the goal of digital transformation. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M. I see myself in my leader: Transformational leadership and its impact on employees’ technology-mediated knowledge sharing in professional service firms. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2023, 33, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Zhang, Q.; Ali, M.; Cappiello, G.; Dhir, A. Linking enterprise social media use, trust and knowledge sharing: Paradoxical roles of communication transparency and personal blogging. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 1056–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, W.; Erickson, G.S. Tacit knowledge acquisition & sharing, and its influence on innovations: A Polish/US cross-country study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 71, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A.; Talwar, S.; Masood, A.; Dhir, A. Does enterprise social media use promote employee creativity and well-being? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliūnienė, J.; Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I.; Vileikis, K. Evaluation of factors determining the efficiency of knowledge sharing process in the Lithuanian National Defence System. J. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 7, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmerita, L.; Kirchner, K.; Nielsen, P. What factors influence knowledge sharing in organizations? A social dilemma perspective of social media communication. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1225–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filstad, C.; Simeonova, B.; Visser, M. Crossing power and knowledge boundaries in learning and knowledge sharing. Learn. Organ. 2018, 25, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koranteng, F.N.; Wiafe, I.; Katsriku, F.A.; Apau, R. Understanding trust on social networking sites among tertiary students: An empirical study in Ghana. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2023, 19, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranić, A.; Tomašević, A.; Alorić, A.; Dankulov, M.M. Sustainability of Stack Exchange Q&A communities: The role of trust. EPJ Data Sci. 2023, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.; Patacconi, A.; Swierzbinski, J.; Williams, J. Knowledge Protection in Firms: A Conceptual Framework and Evidence from HP Labs. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, E.; Jabbarzadeh, A. Knowledge management and social media: A scientometrics survey. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2019, 3, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Understanding the role of social media in organizational change implementation. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 43, 1097–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, A.; Pileggi, S.F.; Hawryszkiewycz, I. Knowledge development, technology and quality of experience in collaborative learning: A perspective from Saudi Arabia universities. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 3085–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Babar, M.; Ahmed, A.; Irfan, M. Analyzing the Impact of Enterprise Social Media on Employees’ Competency through the Mediating Role of Knowledge Sharing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Song, Z.; Du, J.; Li, J. Analysis of the Impact of Personal Psychological Knowledge Ownership on Knowledge Sharing Among Employees in Chinese Digital Creative Enterprises: A Moderated Mediating Variable. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Social Exchange Compiled by M. Murdvee. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. 1968. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/41588618/EconPsy_4_-_Social_exchange.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior as Exchange. SSRN Electron. J. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Zhang, X.; Akanda, A.K.M.E.A.; Hasan, M.N.; Islam, M.M.; Saha, A.; Hossain, M.I.; Rahman, Z. Knowledge Sharing among Students in Social Media: The Mediating Role of Family and Technology Supports in the Academic Development Nexus in an Emerging Country. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, U.G.; Foa, E.B. Resource theory: Interpersonal behavior as exchange. In Social Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research; Gergen, K.J., Greenberg, M.S., Willis, R.H., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Xu, J.; Li, S.; Wei, M. Engaging customers with online restaurant community through mutual disclosure amid the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of customer trust and swift guanxi. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Lewis, M. Supplier motivation to share knowledge: An experimental investigation of a social exchange perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 43, 760–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaheri, N.; Guzman, G.; Stewart, H. Reciprocal knowledge sharing: Exploring professional–cultural knowledge sharing between expatriates and local nurses. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 1483–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, R.; Luan, J. The effects of factors on the motivations for knowledge sharing in online health communities: A benefit-cost perspective. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, M.Z.; Alsabban, A. Knowledge Sharing through Social Media Platforms in the Silicon Age. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Chen, Z.; Yao, P.; Liu, H. A study on the factors influencing users’ online knowledge paying-behavior based on the UTAUT model. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1768–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, S.; Grant, S.B. Antecedents and outcomes of enterprise social network usage within UK higher education. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2023, 53, 608–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: A synthesis and the road ahead. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 328–376. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2800121 (accessed on 22 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Shamsuddin, A.; Wahab, E.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alturki, U.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Almutairy, S. Integrating the Role of UTAUT and TTF Model to Evaluate Social Media Use for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 905968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H.; Petrozhitskaya, E. Is it time for marketing to reappraise B2C relationship management? The emergence of a new loyalty paradigm through blockchain technology. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 159, 113725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.H.; Chua, C.E.H. Monetization for Content Generation and User Engagement on Social Media Platforms: Evidence from Paid Q&A. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, A.; Al-Bashayreh, M.; Al-Oudat, M.; Almajali, D. Blockchain technology adoption for sustainable learning. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Afifa, M.M.; Van, H.V.; Van, T.L.H. Blockchain adoption in accounting by an extended UTAUT model: Empirical evidence from an emerging economy. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2022, 21, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.Z.; Barbera, E.; Rasool, S.F.; Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P.; Mohelská, H. Adoption of social media-based knowledge-sharing behaviour and authentic leadership development: Evidence from the educational sector of Pakistan during COVID-19. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 27, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.W.; Bi, N. Too close to lie to you: Investigating availability management on multiple communication tools across different social relationships. Libr. Hi Tech 2023, 41, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. Ambient Awareness and Knowledge Acquisition: Using Social Media to Learn “Who Knows What” and “Who Knows Whom”. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 747–762. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26628649 (accessed on 4 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. Social media, knowledge sharing, and innovation: Toward a theory of communication visibility. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 796–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.M.; Pileggi, S.F.; Sohaib, O. Social Media Analysis to Enhance Sustainable Knowledge Management: A Concise Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami Pour, M.; Taheri, F. Personality traits and knowledge sharing behavior in social media: Mediating role of trust and subjective well-being. Horizon 2019, 27, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Khan, M.J. Do social networking applications support the antecedents of knowledge sharing practices? VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2019, 49, 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, L.; Ayesh, A. Multimodal motivation modelling and computing towards motivationally intelligent E-learning systems. CCF Trans. Pervasive Comput. Interact. 2023, 5, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, F.A.; Belas, J.; Jabeen, F.; Bresciani, S. The influence of motivations to share knowledge in preventing knowledge sabotage occurrences: An empirically tested motivational model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 192, 122571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.L. Will extrinsic motivation motivate or demotivate knowledge contributors? A moderated mediation analysis. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 2255–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Jia, X.; Huang, Q. How do information overload and message fatigue reduce information processing in the era of COVID-19? An ability–motivation approach. J. Inf. Sci. 2022, 01655515221118047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Nazir, T.; Ahmad, M.S. Unraveling the relationship between workplace dignity and employees’ tacit knowledge sharing: The role of proactive motivation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Parker, S.K.; Chen, Z.; Lam, W. How does the social context fuel the proactive fire? A multilevel review and theoretical synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, A.; Jayawardena, N.S.; Pereira, V.; Sampat, B. Assessing retailer readiness to use blockchain technology to improve supply chain performance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2022. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H.; Agrawal, S.; Lin, S.-M.; Liang, W.-L. Learning communities, social media, and learning performance: Transactive memory system perspective. Comput. Educ. 2023, 203, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D. How does the negotiation between “me” and “we” in professional identity influence interpersonal horizontal knowledge sharing in multinational enterprises: A conceptual model. Int. Bus. Rev. 2023, 32, 102137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Deshpande, R.; Zaltman, G. Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. The impact of initial consumer trust on intentions to transact with a web site: A trust building model. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, R. How knowledge contributor characteristics and reputation affect user payment decision in paid Q&A? An empirical analysis from the perspective of trust theory. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.Y.N. Effects of organizational culture, affective commitment and trust on knowledge-sharing tendency. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunttu, L.; Neuvo, Y. Balancing learning and knowledge protection in university-industry collaborations. Learn. Organ. 2019, 26, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. Available online: https://journals.aom.org/doi/abs/10.5465/256727 (accessed on 5 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.D. Blockchain: The emerging technology of digital trust. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 45, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. User perceptions of algorithmic decisions in the personalized AI system: Perceptual evaluation of fairness, accountability, transparency, and explainability. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2020, 64, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguez, R.C.D.S.; Naranjo-Zolotov, M. Business not as usual: Understanding the drivers of employees’ tacit knowledge sharing behavior in a teleworking environment. In Proceedings of the 2022 17th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Madrid, Spain, 22–25 June 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Nham, T.P.; Froese, F.J.; Malik, A. Motivation and knowledge sharing: A meta-analysis of main and moderating effects. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 998–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, E.J. Fostering organizational learning through leadership and knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1408–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Han, S.H. User experience framework for understanding user experience in blockchain services. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2022, 158, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.A.; Khurshid, M.M. Factors Impacting the Behavioral Intention to Use Social Media for Knowledge Sharing: Insights from Disaster Relief Practitioners. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 18, 269–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, W.N.W.; Razali, N.A.M.; Wook, M.; Ishak, K.K.; Zainudin, N.M.; Hasbullah, N.A.; Ramli, S. Evaluation of blockchain-based data sharing acceptance among intelligence community. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e80b/ca98ed21b2b685904d7e2e974021e4e1fc82.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chan, A.; Zhong, J.; Yu, X. Creativity and social alienation: The costs of being creative. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1252–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korman, A.K.; Wittig-Berman, U.; Lang, D. Career Success and Personal Failure: Alienation in Professionals and Managers. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; Meredith, P.J.; Rose, T.A. Exploring mentalization, trust, communication quality, and alienation in adolescents. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Huang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, S. How does perceived negative workplace gossip influence employee knowledge sharing behavior? An explanation from the perspective of social information processing. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 113, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatiti, P. Use of information and communication technologies to support knowledge sharing in development organisations. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Stud. 2022, 13, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A.; Zhang, Q.; Kaur, P.; Papa, A.; Dhir, A. Untangling the role of power in knowledge sharing and job performance: The mediating role of discrete emotions. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 873–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, M.; Liu, X.; Yang, J. Why Should I Pay for E-Books? An Empirical Study to Investigate Chinese Readers’ Purchase Behavioural Intention in the Mobile Era; The Electronic Library: Hong Kong, China, 2017; Volume 35, pp. 472–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.B.; Nguyen, D.T.N. Stimulating knowledge-sharing behaviours through ethical leadership and employee trust in leadership: The moderating role of distributive justice. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Saeed, I.; Zada, M.; Nisar, H.G.; Ali, A.; Zada, S. The positive side of overqualification: Examining perceived overqualification linkage with knowledge sharing and career planning. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 993–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, M.; Feng, B. The effect of work area on work alienation among China’s grassroots judicial administrators. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, L.Y.; Ng, C.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. Social media engagement in the maritime industry during the pandemic. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 192, 122553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Description | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| OR 1 | I will receive a higher salary in return for my knowledge sharing | [43] |

| OR 2 | I will receive a higher bonus in return for my knowledge sharing | |

| OR 3 | I will receive increased promotion opportunities in return for my knowledge sharing | |

| OR 4 | I will receive increased job security in return for my knowledge sharing | |

| RB 1 | I strengthen ties between existing members of the organization and myself | [43] |

| RB 2 | I expand the scope of my association with other organization members | |

| RB 3 | I expect to receive knowledge in return when necessary | |

| RB 4 | I believe that my future requests for knowledge will be answered | |

| ABT 1 | I have a sharing relationship with the members of my work team. We can all freely share our ideas | [4] |

| ABT 2 | I can talk freely with my colleagues about difficulties I am having with my work | |

| ABT 3 | If I share my problems with my colleagues, I know that they will respond constructively and caring | |

| ABT 4 | I believe that the members of my work team have made considerable emotional investments in our working relationship | |

| KS 1 | I share knowledge learned from my own experience | [5] |

| KS 2 | I have the opportunity to learn from others’ experiences | |

| KS 3 | Colleagues include me in discussions about best practices | |

| KS 4 | Colleagues share new ideas with me | |

| TBT 1 | Social media technology is trustworthy | [34] |

| TBT 2 | Social media technology is honest | |

| TBT 3 | Social media technology is transparent and visible | |

| TBT 4 | Social media technology prevents opportunists from making profits | |

| EF 1 | Using social media would enhance my effectiveness in job-related activities | [34] |

| EF 2 | Using social media would enhance the efficiency of my job | |

| EF 3 | I would find it easy to use social media for job-related activities | |

| EF 4 | It would be easy for me to become skillful at using social media technology | |

| JR 1 | In the knowledge-sharing process, social media can be massively used | [34] |

| JR 2 | In the knowledge-sharing process, social media usage is relevant | |

| JR 3 | Social media is relevant for future knowledge-sharing services | |

| JR 4 | The future of knowledge sharing in work-related activities based on social media technology | |

| SA 1 | I feel I am outside the network of resources needed to get practical support to accomplish my mission | [17] |

| SA 2 | I feel alienated from my colleagues | |

| SA 3 | I feel that people around me are just out for themselves and do not really care for anyone else | |

| SA 4 | I feel that there is interpersonal isolation and even a reluctance to communicate within the company actively |

| Variables | Features | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 252 | 52.07 |

| Female | 232 | 47.93 | |

| Age (years) | 18–30 | 171 | 35.33 |

| 31–40 | 158 | 32.64 | |

| 41–50 | 86 | 17.77 | |

| 51 and above | 69 | 14.26 | |

| Education Background | Junior college or less | 57 | 11.78 |

| Undergraduate degree | 301 | 62.19 | |

| Master’s degree | 112 | 23.14 | |

| Doctoral degree and above | 14 | 2.89 | |

| Position | Non-managerial employees | 364 | 75.21 |

| Manager | 93 | 19.21 | |

| Senior/executive manager | 27 | 5.58 | |

| Job experience | 5 years and below | 90 | 18.60 |

| 5–10 years | 168 | 34.71 | |

| Above 10 years | 226 | 46.69 |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational rewards | OR 1 | 0.911 | 0.794 | 0.939 |

| OR 2 | 0.873 | |||

| OR 3 | 0.870 | |||

| OR 4 | 0.909 | |||

| Reciprocal benefits | RB 1 | 0.881 | 0.789 | 0.937 |

| RB 2 | 0.881 | |||

| RB 3 | 0.903 | |||

| RB 4 | 0.887 | |||

| Affect-based trust | ABT 1 | 0.893 | 0.787 | 0.936 |

| ABT 2 | 0.883 | |||

| ABT 3 | 0.896 | |||

| ABT 4 | 0.875 | |||

| Knowledge sharing | KS 1 | 0.892 | 0.803 | 0.942 |

| KS 2 | 0.895 | |||

| KS 3 | 0.897 | |||

| KS 4 | 0.900 | |||

| Technology-based trust | TBT 1 | 0.894 | 0.778 | 0.933 |

| TBT 2 | 0.898 | |||

| TBT 3 | 0.872 | |||

| TBT 4 | 0.862 | |||

| Expectation fulfillment | EF 1 | 0.889 | 0.761 | 0.927 |

| EF 2 | 0.855 | |||

| EF 3 | 0.866 | |||

| EF 4 | 0.878 | |||

| Job relevance | JR 1 | 0.867 | 0.803 | 0.942 |

| JR 2 | 0.909 | |||

| JR 3 | 0.920 | |||

| JR 4 | 0.888 | |||

| Social alienation | SA 1 | 0.897 | 0.819 | 0.948 |

| SA 2 | 0.885 | |||

| SA 3 | 0.924 | |||

| SA 4 | 0.913 |

| OR | RB | ABT | KS | TBT | EF | JR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 0.891 | ||||||

| RB | 0.151 ** | 0.888 | |||||

| ABT | 0.170 ** | 0.191 ** | 0.887 | ||||

| KS | 0.265 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.896 | |||

| TBT | 0.135 ** | 0.056 | 0.192 ** | 0.240 ** | 0.882 | ||

| EF | 0.165 ** | 0.077 | 0.103 * | 0.259 ** | 0.294 ** | 0.872 | |

| JR | 0.190 ** | 0.041 | 0.170 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.180 ** | 0.191 ** | 0.896 |

| Fit Index | χ2/df | PGFI | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | NFI | RFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended value | <3 | >0.5 | >0.90 | >0.90 | <0.08 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 |

| Actual value | 1.09 | 0.779 | 0.944 | 0.932 | 0.014 | 0.967 | 0.962 | 0.997 |

| Path | Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | β | T Stats | p-Value | VIF | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABT→KS | H1 | 0.203 | 0.055 | 3.701 | *** | 1.107 | Supported |

| TBT→KS | H3 | 0.131 | 0.054 | 2.413 | 0.016 * | 1.144 | Supported |

| OR→ABT | H5 | 0.129 | 0.039 | 3.270 | 0.001 ** | 1.021 | Supported |

| RB→ABT | H6 | 0.160 | 0.043 | 3.752 | *** | 1.023 | Supported |

| EF→TBT | H7 | 0.287 | 0.048 | 5.970 | *** | 1.038 | Supported |

| JR→TBT | H8 | 0.128 | 0.044 | 2.890 | 0.004 ** | 1.036 | Supported |

| Indirect Effects | Estimated Value | 95%CI Lower | 95%CI Upper | p | Conclusion (with or without Intermediary) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR→ABT→KS | 0.026 | 0.009 | 0.054 | 0.001 ** | Yes |

| RB→ABT→KS | 0.030 | 0.013 | 0.058 | 0.001 ** | Yes |

| EF→TBT→KS | 0.033 | 0.007 | 0.068 | 0.015 ** | Yes |

| JR→TBT→KS | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.039 | 0.014 ** | Yes |

| Group | Mean | Number | Mean | S.D. | t-Test | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low SA | <3.6828 | 261 | 2.4933 | 0.60463 | −34.263 | 0.000 |

| High SA | >3.6828 | 223 | 5.0751 | 1.02679 |

| Social Alienation | N1 | N2 | β1 | SE1 | β2 | SE2 | Difference | Spooled | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABT→KS | 261 | 223 | 0.421 *** | 0.76 | −0.447 | 0.71 | 0.468 | 0.737 | 6.967 |

| TBT→KS | 0.269 *** | 0.77 | −0.026 | 0.69 | 0.295 | 0.734 | 4.410 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, Y.; Chun, D.; Yin, F.; Zhou, Y. Exploring Motivations and Trust Mechanisms in Knowledge Sharing: The Moderating Role of Social Alienation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316294

Guo Y, Chun D, Yin F, Zhou Y. Exploring Motivations and Trust Mechanisms in Knowledge Sharing: The Moderating Role of Social Alienation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(23):16294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316294

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Yaoyao, Dongphil Chun, Feng Yin, and Yaying Zhou. 2023. "Exploring Motivations and Trust Mechanisms in Knowledge Sharing: The Moderating Role of Social Alienation" Sustainability 15, no. 23: 16294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316294

APA StyleGuo, Y., Chun, D., Yin, F., & Zhou, Y. (2023). Exploring Motivations and Trust Mechanisms in Knowledge Sharing: The Moderating Role of Social Alienation. Sustainability, 15(23), 16294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316294