The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of Ecuador’s Agrarian Policy 2017–2025

3.2. Analysis Methodology

- (i)

- The definition of keywords for coding the analysis reference corpus [41,42], these being the CFS-RAI Principles and SDGs 2 and 12. The keywords were established based on the meaning and relationships of the existing meaning in the description of the CFS-RAI Principles (Table 1) and the targets of SDGs 2 and 12 (Table 2).

- (ii)

- For the quantitative analysis, the Nvivo program was used as a tool [43]. At first, codification was carried out associated with the reference incorporated (CFS-RAI) Principles and ODS 2 and 12 which served to name the nodes. The hierarchical nodes or cases option [44] was not used because it was not a comparison between the documents. Then, we proceeded to the quantification in a matrix of the keywords existing in the policy, referring to H1.

- (iii)

- The qualitative analysis was carried out to contrast the H2. The words were discriminated by analytical coding. The semantic analysis in the context offered by Nvivo was applied, assuming as valid the keywords that have the same meaning, theoretical similarity, and that which correspond to the same semantic field, and discarding those quantified but that do not fit with the reference corpus, are out of context, or repeated. Based on this, the results matrix was adjusted.

4. Results

4.1. Alignment between the CFS-RAI Principles and SDGs 2 and 12

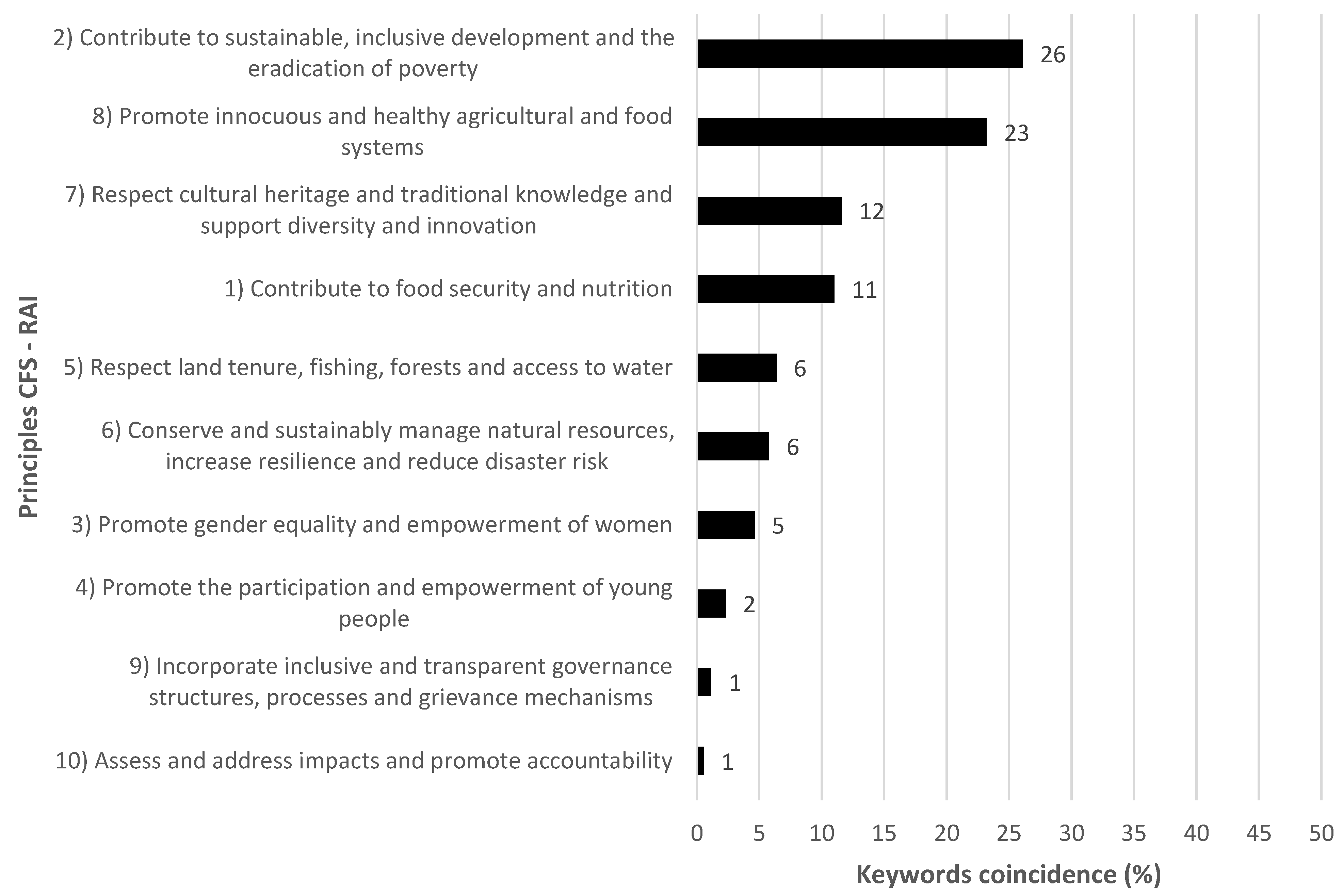

4.2. Incorporation of the CFS-RAI Principles in Ecuador’s Agrarian Policy

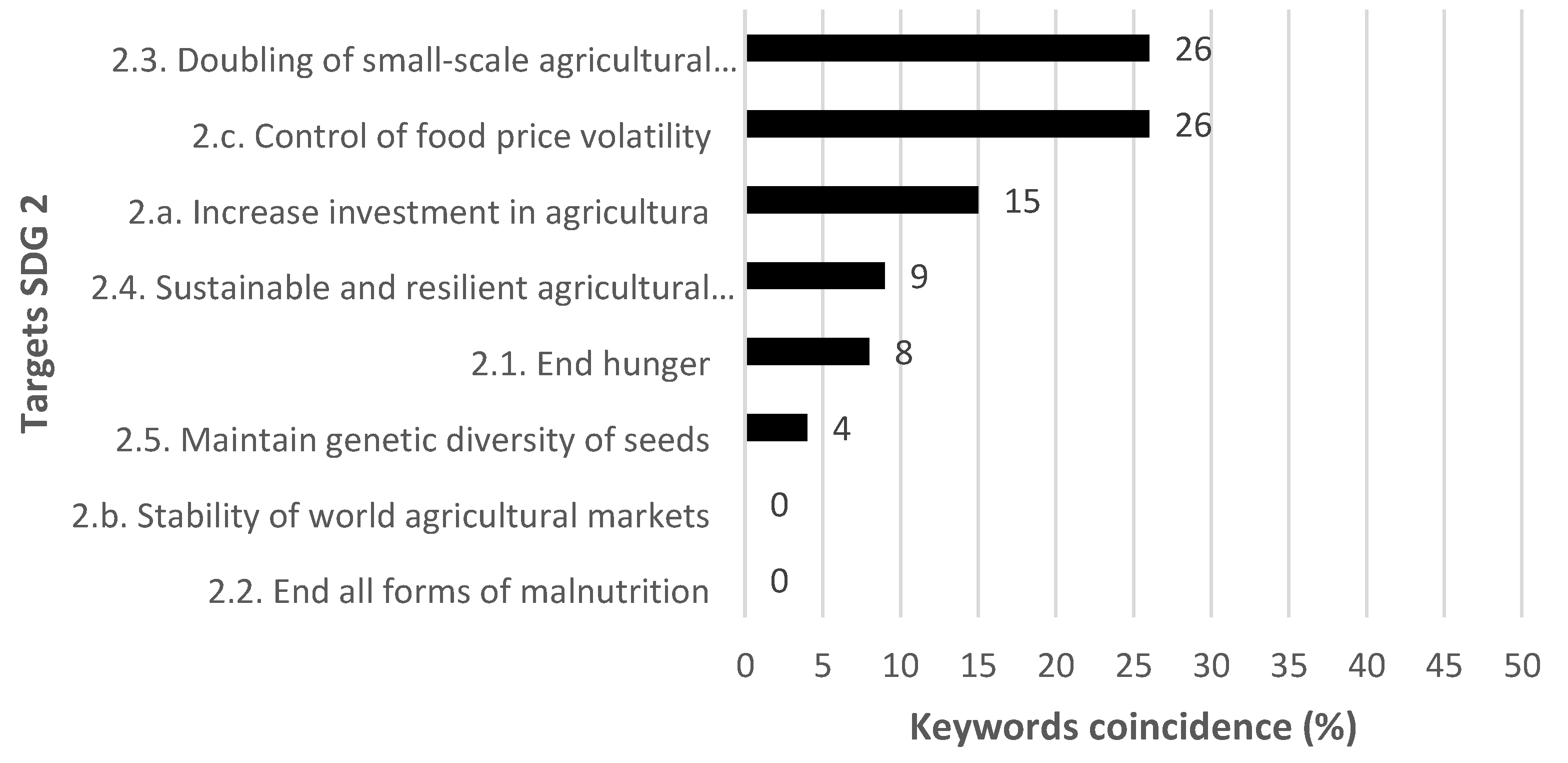

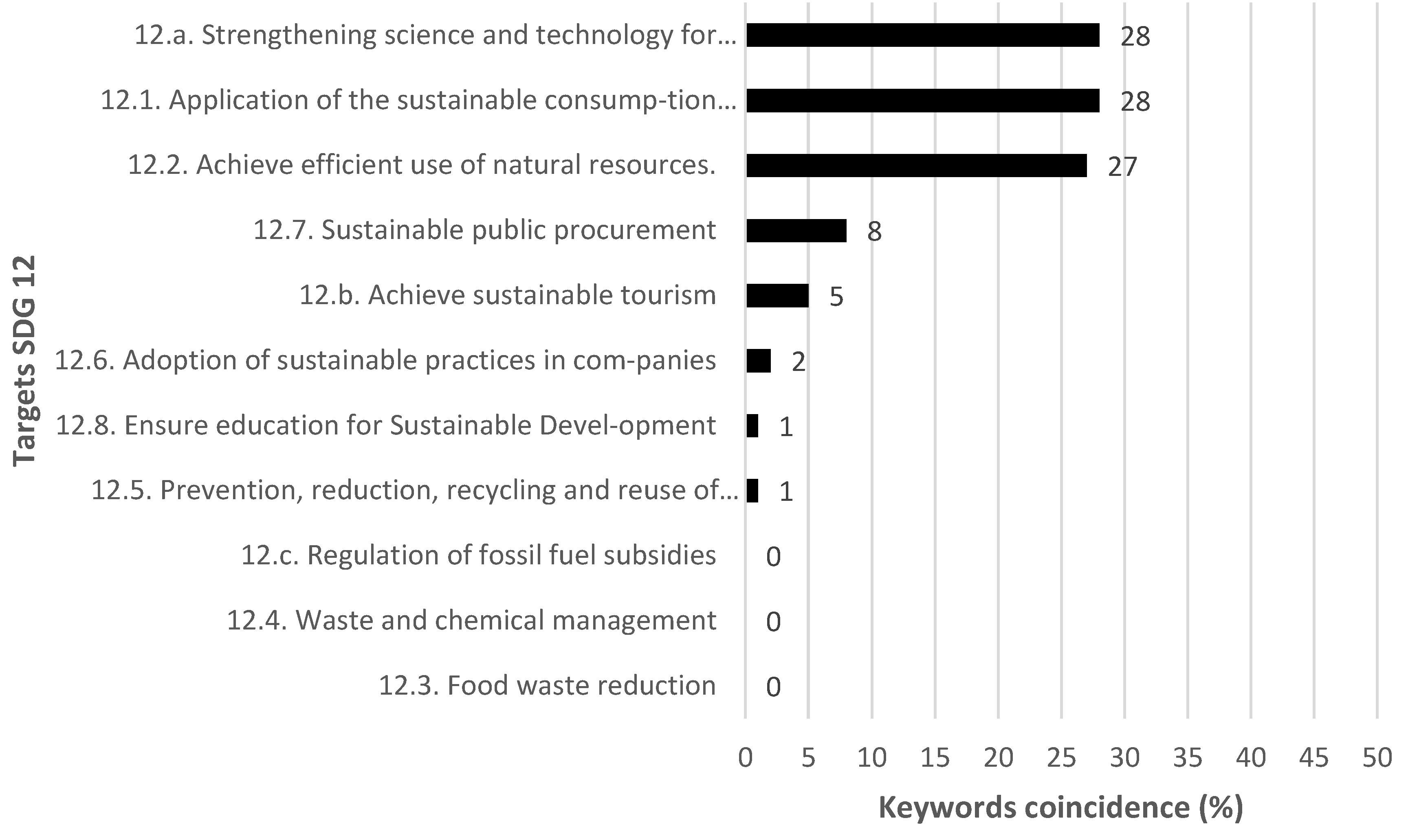

4.3. Incorporation of SDGs 2 and 12 in Ecuador’s Agrarian Policy

5. Discussion

5.1. SDG 2, on the Ecuadorian Agrarian Policy

5.2. SDG 12, on the Ecuadorian Agrarian Policy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| N° | Guidelines | CFS-RAI Principles | SDG 2 | SDG 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Promote sustainable agriculture | 5, 6 | 2.4 | |

| 2 | Establish sustainable production systems | 5, 6 | 2.4 | |

| 3 | Continuous training processes | 4 | 2.3 | |

| 4 | Standardize training programs | 4 | 2.3 | |

| 5 | Articulate participatory innovation programs | 4, 7 | 2.5, 2a | 12.8, 12a |

| 6 | Develop research and technological development through Bio knowledge and ancestral knowledge | 4, 7 | 2.5, 2a | 12.8, 12a |

| 7 | Identify and develop research-based technologies to diversify production and generate resilience in agroproductive systems | 6, 7 | 2.5, 2a | 12.8, 12a |

| 8 | Generate new knowledge and value-adding technologies, promoting the preservation, recovery and use of agrobiodiversity | 6, 7 | 2.5, 2a | 12.8, 12a |

| 9 | Establish value adding mechanisms through associative processes | 2, 3 | 2.5, 2c | |

| 10 | Diversify production considering commercial seasonality and incorporate agroecology standards. | 5, 6, 7 | 2.4 | |

| 11 | Regulations for production to be a self-sustaining sector | 9 | 12.1 | |

| 12 | Mechanisms for adding value to production and associative processes | 2, 3 | 2.5, 2c | |

| 13 | Articulation of research, innovation and exchange of knowledge, science, and technology | 4, 7 | 2.5 | |

| 14 | Provide scientific and technical assistance in research | 4, 7 | 2.5, 2a | 12.8, 12a |

| 15 | Implement thematic tables to suggest and validate research and its dissemination | 9, 10 | 2.5, 2a | 12.8, 12a |

| 16 | Encourage the promotion and marketing of bio trade products | 1, 2 | 2.5, 2a | |

| 17 | Articulate financial services | 2 | 2.3 | |

| 18 | Strengthen the capacities of producers to access credit | 2, 3, 4 | 2.3 | |

| 19 | Promote the strengthening of the financial sectors of the EPS | 2, 3, 4 | 2.3 | |

| 20 | Promote the access of small farmers to the public procurement system | 2, 10 | 12.7 | |

| 21 | Strengthen the capacities of producers as providers of the public procurement system | 2, 4, 10 | 12.7 | |

| 22 | Strengthen the food provision institute | 1 | 2.1 | |

| 23 | Implement associative centers for the provision of support services for production and marketing | 1, 2, 4 | 2.5, 2a | |

| 24 | Continuously improve processes, strategic management and application of information and communication technologies | 9, 10 | 2.5, 2c | |

| 25 | Create and strengthen fair chains of small production at the local and national level | 2, 5, 7 | 2.5, 2b | |

| 26 | Promote the development of marketing support services | 2, 7 | 2.5, 2a, 2b | |

| 27 | Develop interventions to regulate markets, maintain balance in food balances and manage the country’s strategic reserves | 1, 2 | 2.1, 2.5, 2b | |

| 28 | Promote commercial articulation strategies with public and private actors that prioritize the purchase of products from small producers | 1, 2 | 12.7 | |

| 29 | Promote information exchange strategies between ministries | 2, 9, 10 | 12.8 | |

| 30 | Promote product diversification | 6 | 2.5 | |

| 31 | Regulate the market, control smuggling | 2 | 2.5, 2c | |

| 32 | Encourage the production of small and medium agriculture | 5 | 2.3, 2.4 | |

| 33 | Prioritize the ordering and use of the territory with agricultural aptitude | 5 | 12.2 | |

| 34 | Integrate territorial aptitude, ecological footprint and food balance into multisector planning | 2, 5, 9 | 12.2 | |

| 35 | Promote conditions of systemic competitiveness necessary in the strategic chains | 5, 6 | 12.2, 12.5 | |

| 36 | Improve access to the local and international market | 1 | 2.5, 2b | |

| 37 | Preparation and presentation of investment alternatives to attract investment | 9, 10 | ||

| 38 | Promote associativity | 3, 4 | 2.4 | |

| 39 | Strengthen AGROCALIDAD and INAP for pest risk analysis in products for export | 4, 7 | 2.5, 2b | |

| 40 | Promote sustainable production models in the agricultural sector that respond to endogenous territorial development | 2, 5, 6, 7 | 2.4, 2.5, 2a | |

| 41 | Guarantees the quality of the products, strengthens the post-registration control of inputs | 8 | 12.4 | |

| 42 | Maintain and improve sanitary and phytosanitary status | 8 | 12.4 | |

| 43 | Raw material production | 8 | 12.4 | |

| 44 | input ventures | 7 | 12.4 | |

| 45 | Controlled of marketing | 2.5, 2b | ||

| 46 | Regulate imports | 2.5, 2b | ||

| 47 | Strengthen the redistribution, regularization and legalization of land | 5 | 2.4 | |

| 48 | Agricultural and productive use and exploitation of water with a participatory approach | 5 | 2.4 | |

| 49 | Guarantee access to seeds, quality improvement, availability, and promotion | 7 | 2.5 | |

| 50 | Articulation with decentralized autonomous governments | 9 | 2.5, 2a | |

| 51 | Continuous training processes | 3, 4 | 2.3 | |

| 52 | Standardize training programs | 3, 4, 7 | 2.3 | |

| 53 | Articulate participatory innovation programs | 3, 4, 7 | 2.3 | 12.8, 12a |

| 54 | Promote the association of small and medium producers | 3, 4 | 2.3 | |

| 55 | Establish mechanisms for incorporating associative production into production chains linked to priority sectors | 2 | 2.3, 2.5, 2b | |

| 56 | Expand the storage and collection infrastructure for primary products | 5, 9 | 2.5, 2a | |

| 57 | Develop harvest and post-harvest evaluation systems to establish prices for traditional products | 2 | 2.5, 2b | |

| 58 | Develop control mechanism and create regulatory measures in the intermediation links | 1 | 2.5, 2b |

References

- Bengtsson, M.; Alfredsson, E.; Cohen, M.; Lorek, S.; Schroeder, P. Transforming systems of consumption and production for achieving the sustainable development goals: Moving beyond efficiency. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; IFAD; UNCTAD; World Bank Group. Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment that Respects Rights, Livelihoods and Resources. 2010. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaemisc2010d2_en.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- FAO; CFS. Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems. 2014. Available online: www.fao.org/cfs (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Aliaga, R.J.; Ríos-Carmenado, I.D.L.; Howard, F.S.M.; Espinoza, S.C.; Cristóbal, A.H. Integration of the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems CFS-RAI from the Local Action Groups: Towards a Model of Sustainable Rural Development in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Vegas, R. Riesgos globales y capacidades de gobernanza. Claves para la implementación de la Agenda 2030. In Revista Del CLAD Reforma y Democracia; Centro Latinoamericano de Administración para el Desarrollo República Bolivariana de Venezuela: Caracas, Venezuela, 2021; pp. 39–76. Available online: https://clad.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/079-02-G-1.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Cazorla, A.; Negrillo, X. Los Principios IRA como base de investigación entre universidades y empresas. Saeta Digital. Contab. Mark. Empresa 2021, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- von Braun, J.; Birner, R. Designing Global Governance for Agricultural Development and Food and Nutrition Security. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2017, 21, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vía Campesina. ¡Soberanía Alimentaria Ya! 2018, p. 31. Available online: www.eurovía.org (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- Rubio, B. Soberanía alimentaria versus dependencia: Las políticas frente a la crisis alimentaria en América Latina. Mundo Siglo XXI 2011, VII, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mayett-Moreno, Y.; López, J. Beyond Food Security: Challenges in Food Safety Policies and Governance along a Heterogeneous Agri-Food Chain and Its Effects on Health Measures and Sustainable Development in Mexico. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano de la Fuente, J. La gobernanza como forma de acción pública y como concepto analítico. VII Congreso Internacional Sobre La Reforma Del Estado y de Las Administraciones Públicas. 2002, pp. 8–11. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316455781_La_gobernanza_como_forma_de_accion_publica_y_como_concepto_analitico (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- ONU. Transformar Nuestro Mundo: La Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible. United Nations. Rome. 2015. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ares70d1_es.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Gil, J.D.B.; Reidsma, P.; Giller, K.; Todman, L.; Whitmore, A.; van Ittersum, M. Sustainable development goal 2: Improved targets and indicators for agriculture and food security. AMBIO 2018, 48, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanter, D.; Schoob, M.; Baethgen, W.; Berbejillo, J.; Carriquiry, M.; Dobermann, A.; Ferraro, B.; Lanfranco, B.; Mondelli, M.; Penengo, C.; et al. Translating the Sustainable Development Goals into action: Aparticipatory backcasting approach for developming national agricultural transformation pathways. Glob. Food Secur. 2016, 10, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitrón, A.; Santander, G. La Agenda 2030 de Desarrollo sostenible en América Latina y el Caribe: Implicaciones, avances y desafíos. Rev. Int. Coop. Desarro. 2018, 5, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P. Neodesarrollismo y una “vía campesina” para el desarrollo rural: Proyectos divergentes en la revolución ciudadana ecuatoriana. In La Cuestión Agraria y Los Gobiernos de Izquierda en América Latina; Kay, C., Vergara-Camus, L., Eds.; CLACSO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018; pp. 223–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpenöder, F.; Popp, A.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Weindl, I.; Biewald, A.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Dietrich, J.P.; Klein, D.; Kreidenweis, U.; Müller, C.; et al. Large-scale bioenergy production: How to resolve sustainability trade-offs? Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 024011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. National pathways to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGa): A comparative review of scenario modelling tools. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, J.; Brandi, C.; Upendra, R.; Klein, R.; Thiele, R.; Alexander, N.; Scholz, I. Coherent G20 policies towards the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. G20 INSIGHTS 2017, 1–11. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ram-Das/publication/318859046_Coherent_G20_policies_towards_the_2030_Agenda_for_Sustainable_Development/links/5981d1dca6fdccb3100541ef/Coherent-G20-policies-towards-the-2030-Agenda-for-Sustainable-Development.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Horn, P.; Grugel, J. The SDGS in midle-income contruies: Setting or serving domestic development agendas? Evidence from Ecuador. World Dev. 2018, 109, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, P.; Ferrero y de Loma-Osorio, G.; Nabarro, D.; Hainzelin, E.; Guillou, M.; Andersen, I.; Arnold, T.; Astralaga, M.; Beukeboom, M.; Bickersteth, S. Food systems for sustainable development: Proposals for a profound four-part transformation. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapp, J. Responsibility to the rescue? Governing private financial investment in global agriculture. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liversage, H. Responding to “Land Grabbing” and Promoting Responsible Investment in Agriculture. 2010. Available online: https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/USAID_Land_Tenure_2012_Liberia_Course_Module_2_Responding_to_the_Land_Grab_Liversage.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Transnational Institute, & FUHEM Ecosocial. El Acaparamiento Global de Tierras Guía Básica. 2013. Available online: www.tni.org (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Borras, S.M., Jr.; Franco, J.; Wang, C. Tendencias Políticas en Disputa Para la Gobernanza Global del Acaparamiento de Tierras; Transnational Institute. 2010. Available online: https://www.tni.org/files/download/land_grab-globalizations_journal.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Gobierno de España. Plan de Acción para la Implementación de la Agenda 2030. Hacia una Estrategia Española de Desarrollo Sostenible. Spain. 2017. Available online: https://www.mdsocialesa2030.gob.es/agenda2030/documentos/plan-accion-implementacion-a2030.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Gobierno de Navarra. Alineación de las Políticas Públicas Competencia del Gobierno de Navarra con la Agenda 2030 de Desarrollo Sostenible. Navarra, Spain. 2017. Available online: https://gobiernoabierto.navarra.es/sites/default/files/agenda_2030_3223_anexo_i.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Urquijo, J.; Illán, C. Informe de Resultados. Alineamiento de los Programas Presupuestarios de la Generalitat Valenciana con las Metas ODS. 2017. Red Española de Desarrollo Sostenible (REDS). Available online: https://cooperaciovalenciana.gva.es/documents/164015995/174491353/Informe+final+alineamiento+GVA+ODS_Final_20_01_2022.pdf/cc45c943-b0de-4018-977a-534b16e1814d (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- CEPAL. CEPALSTAT Bases de Datos y Publicaciones Estadísticas. 2023. Available online: https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/index.html?lang=es (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Plastun, A.; Makarenko, I.; Grabovska, T.; Situmeang, R.; Bashlai, S. Sustainable Development Goals in ag-riculture and responsible investment: A comparative study of the Czech Republic and Ukraine. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2021, 19, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.; Weitz, N.; Persson, Å.; Trimmer, C. Stockholm Environment Institute SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production-A Review of Research Needs 1 1 SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production A review of research needs Annex to the Formas report Forskning för Agenda 2030: Översikt av forsk. 2018, pp. 1–25. Available online: https://www.sei.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/sdg-12-responsible-consumption-and-production-review-of-research-needs.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Siegel, K.M.; Lima, M.G.B. When international sustainability frameworks encounter domestic politics: The sustainable development goals and agri-food governance in South America. World Dev. 2020, 135, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liendo, R. Desafío boliviano: El cumplimiento de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible desde el sistema agroalimentario campesino indígena. LAJED 2021, 19, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, C.A.S.; Puma, E.M.; Portugal, N.G. Pandemia por COVID-19 y Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible al 2020 COVID-19. Cienc. Lat. 2021, 5, 1627–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2020. In Sustainable Development Report 2020; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781108834209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buele, I.; Zúñiga, D.; Tobar, L. Principles for Responsible Investement in Agriculture and Food Systems and Their Social Impact: Application to Universitary Projects. Acad. Entrep. J. 2021, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IISD. Responsible Investments in Agriculture and Food Systems—A Practical Handbook for Parliamentarians and Parliamentary Advisors; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 9789251335895. [Google Scholar]

- Asamblea Constituyente. Constitución del Ecuador. Asamblea Nacional. Montecristi. Ecuador. 2008, pp. 1–95. Available online: https://www.asambleanacional.gob.ec/es/contenido/constitucion-de-la-republica-del-ecuador (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Diéguez, Y. El Derecho y su Correlación con los Cambios de la Sociedad. 2021, pp. 1–28. Available online: https://www.derechoycambiosocial.com/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Eco, H. Tratado de Semiótica General (Quinta Edición); Editorial Lumen, S. A: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Duque, E. Análisis de contenido mediante análisis de palabras clave: La representación de los participantes en los discursos de Esperanza Aguirre. Mediaciones Soc. 2015, 13, 39–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.F.N.; Garza, H.N.; Rosas, N.M.O. Caracterización semántica de la agroecología regional en América Latina. Región y Soc. 2022, 34, e1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International. Nvivo. 2019. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home/ (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Galsurkar, J.; Singh, M.; Wu, L.; Vempaty, A.; Sushkov, M.; Iyer, D.; Kapto, S.; Varshney, K. Assessing National Development Plans for Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals via Semantic Search. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2018, 32, 11424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, I.; Dávalos, J. Crecimiento económico inclusivo y sostenible en la Agenda 2030: Un análisis crítico desde la perspectiva de la soberanía alimentaria y los derechos de la naturaleza. Iberoam. J. Dev. Stud. 2020, 9, 146–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, P.; Levine, S.; Lipton, M.; Warren-Rodríguez, A. Toward a food secure future: Ensuring food security for sustainable human development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 2016, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Gustafson, D.; Mathys, A. Multi-indicator sustainability assessment of global food systems. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaria Técnica de Planificación. Examen Nacional Voluntario 2. 2018. Available online: www.planificacion.gob.ec (accessed on 21 February 2023).

| CFS-RAI Principles | Keywords |

|---|---|

| 1. Contribute to food security and nutrition | food, nutrition |

| 2. Contribute to sustainable, inclusive development and the eradication of poverty | development, sustainable, poverty |

| 3. Promote gender equality and empowerment of women | gender, empowerment, women |

| 4. Promote the participation and empowerment of young people | youth |

| 5. Respect land tenure, fishing, forests and access to water | land, fishing, forests, water, hydric |

| 6. Conserve and sustainably manage natural resources, increase resilience and reduce disaster risk. | resources, resilience, risks |

| 7. Respect cultural heritage and traditional knowledge and support diversity and innovation | culture, local knowledge |

| 8. Promote safe and healthy agricultural and food systems | productive, innocuous, healthy systems |

| 9. Incorporate inclusive and transparent governance structures, processes and grievance mechanisms | governance |

| 10. Assess and address impacts and promote accountability | effects, accountability |

| No. | Goal Description | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 2: End hunger | ||

| 2.1 | End hunger and ensure access to healthy, nutritious and sufficient food throughout the year. | hunger, undernourishment, food insecurity |

| 2.2 | End all forms of malnutrition of children under 5 years of age, adolescents, pregnant and lactating women and older people. | malnutrition |

| 2.3 | Doubling agricultural productivity and income for small-scale producers through secure and equitable access to land, resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities | productivity, production, income |

| 2.4 | Ensure the sustainability of food production systems and apply resilient agricultural practices. | sustainability, sustainable, resilience, ecosystems, climate |

| 2.5 | Maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, plants, animals and wild species through good management and diversification of seed and plant banks and promote access to benefits derived from the use of genetic resources and traditional knowledge. | seeds, germplasm, genetic resources, breeds, traditional knowledge |

| 2.a | Increase investment in agriculture: rural infrastructure, research, agricultural extension, technological development and plant and livestock gene banks in order to improve agricultural production capacity. | research, technology, irrigation, agricultural extension, germplasm |

| 2.b | Correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets, through the elimination of subsidies for agricultural exports. | market, subsidies, subsidies, exports |

| 2.c | Adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food and derivatives markets and facilitate timely access to information. | market, food safety, prices |

| SDG 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns | ||

| 12.1 | Implementation of the 10-Year Framework on sustainable consumption and production patterns | sustainable production, sustainable consumption, policies |

| 12.2 | Achieve sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources. | efficient use, material consumption, material footprint |

| 12.3 | Halve global per capita food waste in sales at the consumer level and reduce food losses in production, supply and harvest chains. | food losses, waste |

| 12.4 | Achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and waste throughout their life cycle, in accordance with international frameworks. | hazardous waste, chemical waste, environmental agreements |

| 12.5 | Reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse. | waste, reduce, recycle, reuse |

| 12.6 | Encourage companies to adopt sustainable practices and incorporate information on sustainability. | companies, sustainability |

| 12.7 | Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities. | public procurement, politics |

| 12.8 | Ensure that the world population has information and knowledge for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature. | education, sustainable development, policies, lifestyles |

| 12.a | Strengthen scientific and technological capacity to move towards more sustainable consumption and production patterns. | research, technologies |

| 12.b | Apply instruments to monitor effects on sustainable development, in order to achieve sustainable tourism. | tourism, work |

| 12.c | Rationalize inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, removing market distortions by restructuring tax systems and removing subsidies. | subsidies, fossil fuels |

| CFS-RAI Principles | SDG 2: Zero Hunger | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Target * | No. |

| + | + | End hunger | Target 2.1. | ||||||||

| + | + | End all forms of malnutrition. | Target 2.2. | ||||||||

| + | + | + | + | Doubling of small-scale agricultural productivity and income. | Target 2.3. | ||||||

| + | + | + | + | Sustainable and resilient agricultural practices | Target 2.4. | ||||||

| + | + | Maintain genetic diversity of seeds. | Target 2.5. | ||||||||

| + | + | Increase investment in agriculture | Target 2.a | ||||||||

| + | + | + | Stability of world agricultural markets | Target 2.b | |||||||

| + | + | Control of food price volatility | Target 2.c | ||||||||

| SDG 12: Sustainable production and consumption | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Target * | No. |

| + | + | Application of the sustainable consumption and production framework | Target 12.1. | ||||||||

| + | + | Achieve efficient use of natural resources. | Target 12.2. | ||||||||

| + | Food waste reduction | Target 12.3. | |||||||||

| + | + | Waste and chemical management | Target 12.4. | ||||||||

| + | Prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse of waste. | Target 12.5. | |||||||||

| + | Adoption of sustainable practices in companies | Target 12.6. | |||||||||

| + | Sustainable public procurement | Target 12.7. | |||||||||

| + | + | Ensure education for Sustainable Development | Target 12.8. | ||||||||

| + | Strengthening science and technology for sustainability | Target 12.a | |||||||||

| + | Achieve sustainable tourism | Target 12.b | |||||||||

| + | + | Regulation of fossil fuel subsidies | Target 12.c | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Requelme, N.; Afonso, A. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215985

Requelme N, Afonso A. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):15985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215985

Chicago/Turabian StyleRequelme, Narcisa, and Ana Afonso. 2023. "The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador" Sustainability 15, no. 22: 15985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215985

APA StyleRequelme, N., & Afonso, A. (2023). The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador. Sustainability, 15(22), 15985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215985