Creative and Happy Individuals Concerned about Climate Change: Evidence Based on the 10th Round of the European Social Survey in 22 Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Understanding the Interaction between the Individual and the Environment

1.2. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaufman, J.C.; Sternberg, R.J. (Eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781107188488. [Google Scholar]

- Shalley, C.E.; Hitt, M.A.; Zhou, J. The Oxford Handbook of Creativity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cropley, D.H. Homo Problematis Solvendis—Problem-Solving Man: A History of Human Creativity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9789811331008. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, R.; Brem, A. Creativity for Sustainability: An Integrative Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, A.; Puente-Díaz, R. Creativity, Innovation, Sustainability: A Conceptual Model for Future Research Efforts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamannaeifar, M.; Hossain, P.M. Psychological Effects of Spiritual Intelligence and Creativity on Happiness. Int. J. Med. Investig. 2019, 8, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Usai, A.; Orlando, B.; Mazzoleni, A. Happiness as a Driver of Entrepreneurial Initiative and Innovation Capital. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020, 21, 1229–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada-Tello, E. Subjective Well-Being Based on Creativity and the Perception of Happiness. Retos 2019, 9, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, Z.; Heidari, A. The Relationship between Happiness, Subjective Well-Being, Creativity and Job Performance of Primary School Teachers in Ramhormoz City. Int. Educ. Stud. 2016, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.S.; Tan, S.A.; Mohd Hashim, I.H.; Lee, M.N.; Ong, A.W.H.; Yaacob, S.N.B. Problem-Solving Ability and Stress Mediate the Relationship between Creativity and Happiness. Creat. Res. J. 2019, 31, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravina-Ripoll, R.; Tobar-Pesantenz, L.B.; Galiano-Coronil, A.; Marchena-Domínguez, J. Happiness Management and Social Marketing: A Wave of Sustainability and Creativity; Peter Lang: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll, R.R.; Pesantez, L.B.T.; Domínguez, J.M. (Eds.) Happiness Management: A Lighthouse for Social Wellbeing, Creativity and Sustainability; Peter Lang: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A. The Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development for Well-Being in Organizations. Res. Top. Front. Psychol. Sect. Org. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, A.D.; Rosen, M.A. Opening the Black Box of Psychological Processes in the Science of Sustainable Development: A New Frontier. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2018, 2, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsella, A.J.; Mustakova-Possardt, E.; Lyubansky, M.; Basseches, M.; Editors, J.O. International and Cultural Psychology Series Editor: Toward a Socially Responsible Psychology for a Global Era; Kluwer Academic/Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, C. Sustainable Happiness: How Happiness Studies Can Contribute to a More Sustainable Future. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerret, D.; Orkibi, H.; Ronen, T. Green Perspective for a Hopeful Future: Explaining Green Schools’ Contribution to Environmental Subjective Well-Being. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2014, 18, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aknin, L.B.; Dunn, E.W.; Norton, M.I. Happiness Runs in a Circular Motion: Evidence for a Positive Feedback Loop between Prosocial Spending and Happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 13, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluda-Verdú, I.; Senent-Valero, M.; Casas-Escolano, M.; Matijasevich, A.; Pastor-Valero, M. Fear for the Future: Eco-Anxiety and Health Implications, a Systematic Review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Jain, P. Eco-Anxiety and Environmental Concern as Predictors of Eco-Activism. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1084, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.K.; Passmore, H.A.; Howell, A.J.; Zelenski, J.M.; Yang, Y.; Richardson, M. The Continuum of Eco-Anxiety Responses: A Preliminary Investigation of Its Nomological Network. Collabra. Psychol. 2023, 9, 67838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Urbán, R.; Nagy, B.; Csaba, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Kovács, K.; Varga, A.; Dúll, A.; Mónus, F.; Shaw, C.A.; et al. The Psychological Consequences of the Ecological Crisis: Three New Questionnaires to Assess Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, and Ecological Grief. Clim. Risk. Manag. 2022, 37, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Csaba, B.; Nagy, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Dúll, A.; Rácz, J.; Demetrovics, Z. Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety and Environmental Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Newman, D.B. Eco-Anxiety in Daily Life: Relationships with Well-Being and pro-Environmental Behavior. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 4, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caple, D. Creativity in Design of Green Workplaces. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 824. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, C.R.G. Approaches to Sustainable and Responsible Entrepreneurship: Creativity, Innovation, and Intellectual Capital as Drivers for Organization Performance. In Building an Entrepreneurial and Sustainable Society; IGI Global: Hershey, PN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, S.L.; Hancock, T.; Bland, J.; van den Bosch, M.; Jansson, J.K.; Johnson, C.C.; Kondo, M.; Katz, D.; Kort, R.; Kozyrskyj, A.; et al. Eighth Annual Conference of in VIVO Planetary Health: From Challenges to Opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Gatzweiler, F.W.; Kumar, M. An Evolutionary Complex Systems Perspective on Urban Health. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2021, 75, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miciukiewicz, K. Can a Park Save the City?: Hopes and Pitfalls of the London National Park City. Przegląd Kult. 2020, 2020, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, V.; Podpadec, T. Young People, Climate Change and Fast Fashion Futures. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhan, N.E.; Çiçek, S.; Kocaağa, G. Critical and Creative Perspectives of Gifted Students on Global Problems: Global Climate Change. Think Ski. Creat. 2022, 46, 101131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabaja, Z.F. Exploring an Unfamiliar Territory: A Study on Outdoor Education in Lebanon. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2023, 23, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassagne, N.; Everingham, P. Buen Vivir: Degrowing Extractivism and Growing Wellbeing through Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1909–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, A.V. Biophilia and Human Health. In Programming for Health and Wellbeing in Architecture; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Regmi, S.; Johnson, B.; Dahal, B.M. Analysing the Environmental Values and Attitudes of Rural Nepalese Children by Validating the 2-MEV Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfelder, M.L.; Bogner, F.X. Between Science Education and Environmental Education: How Science Sustainability between Science Education and Environmental Education: How Science Motivation Relates to Environmental Values. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atari, M.; Afhami, R.; Mohammadi-Zarghan, S. Exploring Aesthetic Fluency: The Roles of Personality, Nature Relatedness, and Art Activities. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2018, 14, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.E.; Pelletier, L.G. Is Nature Relatedness a Basic Human Psychological Need? A Critical Examination of the Extant Literature. Can. Psychol. 2019, 60, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Profice, C.C.; Collado, S. Nature Experiences and Adults’ Self-Reported pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Role of Connectedness to Nature and Childhood Nature Experiences. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, J.A.; Marshall, N.A.; Birtles, A.; Case, P.; Curnock, M.I.; Gurney, G.G. On the Relationship between Attitudes and Environmental Behaviors of Key Great Barrier Reef User Groups. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdukovic, I.; Gilibert, D.; Fointiat, V. Structural Confirmation of the 24-Item Environmental Attitude Inventory/Confirmación Estructural Del Inventario de Actitudes Ambientales de 24 Ítems. Psyecology 2019, 10, 184–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapeller, M.L.; Jäger, G. Threat and Anxiety in the Climate Debate—An Agent-Based Model to Investigate Climate Scepticism and Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Song, D.; Li, C. Environmental Responsibility Decisions of a Supply Chain under Different Channel Leaderships. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 26, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Xu, X.; Bai, G. Corporate Environmental Responsibility, CEO’s Tenure and Innovation Legitimacy: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.M.M.; Ahmed, U.; Ismail, A.I.; Mozammel, S. Going Intellectually Green: Exploring the Nexus between Green Intellectual Capital, Environmental Responsibility, and Environmental Concern towards Environmental Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashkiv, I.; Kupalova, H.; Goncharenko, N.; Andrusiv, U.; Streimikis, J.; Lyashenko, O.; Yakubiv, V.; Lyzun, M.; Lishchynsky, I.; Saukh, I. Environmental Responsibility as a Prerequisite for Sustainable Development of Agricultural Enterprises. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 2973–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.H.P.; Patterson, I.; Packer, J.; Pegg, S. Identifying the Satisfactions Derived from Leisure Gardening by Older Adults. Ann. Leis. Res. 2010, 13, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J.; Corraliza, J.A.; Martín, R. Rural-Urban Differences in Environmental Concern, Attitudes, and Actions. Rural-Urban Differ. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 21, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J. Early Childhood Educators’ Use of Natural Outdoor Settings as Learning Environments: An Exploratory Study of Beliefs, Practices, and Barriers. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, R.; Morais, D.; Pinheiro, J. Life Experiences and the Formation of Pro-Ecological Commitment: Exploring the Role of Spirituality/Experiencias de Vida y La Formación Del Compromiso pro-Ecológico: Explorando El Papel de La Espiritualidad. Psyecology 2018, 9, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, O.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Roussiau, N.; Ortiz-Valdez, A.; Guillard, M.; Wittenberg, I.; Fleury-Bahi, G. Connectedness to Nature and Its Relationship with Spirituality, Wellbeing and Sustainable Behaviour. Psyecology 2020, 11, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, A.; Raimi, K.T. Environmental Peer Persuasion: How Moral Exporting and Belief Superiority Relate to Efforts to Influence Others. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouillet, R.; Doron, J.; Combes, R. Metacognitive Beliefs, Environmental Demands and Subjective Stress States: A Moderation Analysis in a French Sample. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 101, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. “Everything Has to Die One Day”: Children’s Explorations of the Meanings of Death in Human-Animal-Nature Relationships. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.M.Y. Views on Creativity, Environmental Sustainability and Their Integrated Development. Creat. Educ. 2018, 9, 719–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, G.N.; Ghelich Khani, N. Defining Design for Sustainability and Conservation Mindsets. Cuad. Cent. Estud. Diseño Comun. 2021, 321, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y. True Sustainable Development of Green Technology: The Influencers and Risked Moderation of Sustainable Motivational Behavior. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J. Institutionalized Collective Action and the Relationship between Beliefs about Environmental Problems and Environmental Actions: A Cross-National Analysis. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 75, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media Use, Environmental Beliefs, Self-Efficacy, and pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.T.; Lin, H.C. Sustainable Development: The Effects of Social Normative Beliefs On Environmental Behaviour. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young Travelers’ Intention to Behave pro-Environmentally: Merging the Value-Belief-Norm Theory and the Expectancy Theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, C.T.; Takahashi, B.; Zwickle, A.; Besley, J.C.; Lertpratchya, A.P. Sustainability Behaviors among College Students: An Application of the VBN Theory. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, M.; Aldieri, L.; Dhayal, K.S.; Agrawal, S. Education 4.0: Can It Be a Component of the Sustainable Well-Being of Students? Available online: https://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/978-1-6684-4981-3.ch014 (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Hou, W.K.; Lai, F.T.T.; Hougen, C.; Hall, B.J.; Hobfoll, S.E. Measuring Everyday Processes and Mechanisms of Stress Resilience: Development and Initial Validation of the Sustainability of Living Inventory (SOLI). Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahar, F.; Sahin, E. An Associational Research on Turkish Children’s Environmentally Responsible Behaviors, Nature Relatedness, and Motive Concerns. Sci. Educ. Int. 2017, 28, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalot, F.; Ahvenharju, S.; Minkkinen, M.; Wensing, E. Aware of the Future?: Development and Validation of the Futures Consciousness Scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 36, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M.T.J.; Powell, R.B.; Hallo, J.C. A Review of the Foundational Processes That Influence Beliefs in Climate Change: Opportunities for Environmental Education Research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Biel, A. Investment Institutions’ Beliefs about and Attitudes toward Socially Responsible Investment (SRI): A Comparison between SRI and Non-SRI Management. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawatzky, A.; Cunsolo, A.; Shiwak, I.; Flowers, C.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Gillis, D.; Middleton, J.; Wood, M.; Harper, S.L. “It Depends…”: Inuit-Led Identification and Interpretation of Land-Based Observations for Climate Change Adaptation in Nunatsiavut, Labrador. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Meng, K.; Liu, W.; Xue, L. Public Attitudes toward Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from Five Chinese Cities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How Materialism Affects Environmental Beliefs, Concern, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Choi, Y.J. Influencing Factors of Chinese Consumers ’ Purchase Intention to Sustainable Apparel Products: Exploring Consumer “ Attitude—Behavioral Intention ” Gap. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, G.; Finn, S.; Joe, J.R.; Hoover, E.; Gone, J.P.; Leftliand-Begay, C.; Hill, S. Native American Perspectives on Health and Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 125002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Carmen Aguilar-Luzón, M.; Benítez, I. Advances in Environmental Psychology Regarding the Promotion of Wellbeing and Quality of Life/Avances de La Psicología Ambiental Ante La Promoción Del Bienestar y La Calidad de Vida. Psyecology 2018, 9, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amérigo, M.; García, J.A.; López-Santiago, S. The Effects of Emotions on the Generation of Environmental Arguments/Efectos de Las Emociones En La Generación de Argumentos Sobre El Medio Ambiente Natural. Psyecology 2018, 9, 204–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravina-Ripoll, R.; Domínguez, J.M.; Montañés-Del Río, M.Á. Happiness Management in the Age of Industry 4.0. Retos 2019, 9, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.L. Challenges and Inspirations of Nature-Based Spirituality Adherents Who Aspire to Address the Ecocrisis; Convention Presentation, Topic 27; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, A.J.; Passmore, H.A.; Buro, K. Meaning in Nature: Meaning in Life as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Nature Connectedness and Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, E. Nature: For Religion Conservation. J. Study Relig. Nat. Cult. 2017, 2, 197–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ashton, M.C.; Choi, J.; Zachariassen, K. Connectedness to Nature and to Humanity: Their Association and Personality Correlates. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beery, T.H. Nordic in Nature: Friluftsliv and Environmental Connectedness. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 94–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Hallam, J. Exploring the Psychological Rewards of a Familiar Semirural Landscape: Connecting to Local Nature through a Mindful Approach. Humanist. Psychol. 2013, 41, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Three Good Things in Nature: Noticing Nearby Nature Brings Sustained Increases in Connection with Nature. Psyecology 2017, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Kaiser, F.G.; Roczen, N. One for All?: Connectedness to Nature, Inclusion of Nature, Environmental Identity, and Implicit Association with Nature. Eur. Psychol. 2011, 16, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. Happiness Is in Our Nature: Exploring Nature Relatedness as a Contributor to Subjective Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, R.F.; Lewis, T.F.; Myers, J.E.; Wahesh, E.; Iversen, R. Relationship between Nature Relatedness and Holistic Wellness: An Exploratory Study. J. Humanist. Couns. 2014, 53, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.A.; Howell, A.J. Eco-Existential Positive Psychology: Experiences in Nature, Existential Anxieties, and Well-Being. Humanist. Psychol. 2014, 42, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hajj, R.; Khater, C.; Tatoni, T.; Adam, A.A.; Errol, V. Integrating Conservation and Sustainable Development Through Adaptive Co-Management in UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. Conserv. Soc. 2017, 15, 217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, F.; Preston, J.L. Green as the Gospel: The Power of Stewardship Messages to Improve Climate Change Attitudes. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2019, 13, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, C.M.; Winter, P.L.; Schultz, P.W.; Omoto, A.M.; Tabanico, J.J. Getting to Know Nature: Evaluating the Effects of the Get to Know Program on Children’s Connectedness with Nature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Sramek, B.; Robinson, J.L.; Darby, J.L.; Thomas, R.W. Exploring the Differential Roles of Environmental and Social Sustainability in Carrier Selection Decisions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankenau, G.R. Fostering Connectedness to Nature in Higher Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Orville, H. The Relationship between Sustainability and Creativity. Cadmus 2019, 4, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.; Ho, S.J.; Huang, T.C. The Development of a Sustainability-Oriented Creativity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship Education Framework: A Perspective Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmetty, S.; Glaveanu, V.P.; Collin, K.; Forsman, P. (Un)Sustainable Creativity? Different Manager-Employee Perspectives in the Finnish Technology Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.A.; Rauch, E. Axiomatic Design for Creativity, Sustainability, and Industry 4.0. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 301, 00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, M.; Esposito, L.; Parziale, A.; Dhayal, K.S.; Agrawal, S.; Giri, A.K.; Loan, N.T. The Role of Greener Innovations in Promoting Financial Inclusion to Achieve Carbon Neutrality: An Integrative Review. Economies 2023, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mróz, A.; Ocetkiewicz, I. Creativity for Sustainability: How Do Polish Teachers Develop Students’ Creativity Competence? Analysis of Research Results. Sustainability 2021, 13, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzola, A.M.; Petrakis, P.E. The Sustainability of Creativity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoto, S.; Jonason, P.K. Intelligence as a Psychological Mechanism for Ecotheory of Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2019, 31, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vliert, E.; Murray, D.R. Climate and Creativity: Cold and Heat Trigger Invention and Innovation in Richer Populations. Creat. Res. J. 2018, 30, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Tsuda, A. The Psychology of Harmony and Harmonization: Advancing the Perspectives for the Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; Williams, E.G. Organizational Citizenship Behavior Toward the Environment Scale. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The Nature Relatedness Scale. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, J. The Jewel in the Corona: Crisis, the Creativity of Social Dreaming, and Climate Change. J. Soc. Work Pract. 2020, 34, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, L. Collective Creativity and Wellbeing Dispositions: Children’s Perceptions of Learning through Drama. Think Ski. Creat. 2023, 47, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Rushing, A.J.; Gallinat, A.S.; Primack, R.B. Creative Citizen Science Illuminates Complex Ecological Responses to Climate Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 720–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuvieco, E.; Burgui-Burgui, M.; Orellano, A.; Otón, G.; Ruíz-Benito, P. Links between Climate Change Knowledge, Perception and Action: Impacts on Personal Carbon Footprint. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Tong, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X. Impact of Climate Change Beliefs on Youths’ Engagement in Energy-Conservation Behavior: The Mediating Mechanism of Environmental Concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, J.E. Organizational Creativity and Sustainability-Oriented Innovation as Drivers of Sustainable Development: Overcoming Firms’ Economic, Environmental and Social Sustainability Challenges. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Bucci, O.; Gori, A. High Entrepreneurship, Leadership, and Professionalism Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1480. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Education for Sustainable Development in the Framework of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Resolution 70/1, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Baeyens, A.; Goffin, T. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 [without Reference to a Main Committee (A/70/L.1)] 70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Sengupta, M. The Sustainable Development Goals: An Assessment of Ambition. Available online: https://www.e-ir.info/pdf/60984 (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- United Nations. General Assembly UN-Resolution 70/204. In UN-General Assembly—Seventieth Session; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R.; Kraslawski, A. Creativity Enables Sustainable Development: Supplier Engagement as a Boundary Condition for the Positive Effect on Green Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyaningsih, I.; Ananda, R.; Fauziddin, M.; Pattiasina, P.J.; Anwar, M. Developing Student Characters to Have Independent, Responsible, Creative, Innovative and Adaptive Competencies towards the Dynamics of the Internal and External World. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 9332–9345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Long, R.; Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, H. Evolution of the Knowledge Mapping of Climate Change Communication Research: Basic Status, Research Hotspots, and Prospects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, S.; Dhammi, S.; Guha, A. Climate Crisis and Language—A Constructivist Ecolinguistic Approach. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 3581–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briandana, R.; Saleh, M.S.M. Implementing Environmental Communication Strategy Towards Climate Change Through Social Media in Indonesia. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2022, 12, 12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, R. CSR, CSA, or CPA? Examining Corporate Climate Change Communication Strategies, Motives, and Effects on Consumer Outcomes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, J.P.H.; Shang, Q. Are Creative Workers Happier in Chinese Cities? The Influence of Work, Lifestyle, and Amenities on Urban Well-Being. Urban Geogr. 2014, 35, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.; Chuah, C.Q.; Lee, S.T.; Tan, C.S. Being Creative Makes You Happier: The Positive Effect of Creativity on Subjective Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K. Cultural Values and Sustainable Tourism Governance in Bhutan. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A. Investigating Sustainable Education and Positive Psychology Interventions in Schools Towards Achievement of Sustainable Happiness and Wellbeing for 21 St Century Pedagogy and Curriculum. ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 19481–19494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, J.L.S.; De Juana-Espinosa, S.; Martínez-buelvas, L.; Abarca, Y.V.; Tirado, J.O. Organizational Happiness Dimensions as a Contribution to Sustainable Development Goals: A Prospective Study in Higher Education Institutions in Chile, Colombia and Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.E.S.; Carmen, B.P.B.; Luminarias, M.E.P.; Mangulabnan, S.A.N.B.; Ogunbode, C.A. An Investigation into the Relationship between Climate Change Anxiety and Mental Health among Gen Z Filipinos. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 7448–7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, E.L.; Jennings, N.; Kioupi, V.; Thompson, R.; Diffey, J.; Vercammen, A. Psychological Responses, Mental Health, and Sense of Agency for the Dual Challenges of Climate Change and the COVID-19 Pandemic in Young People in the UK: An Online Survey Study. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e726–e738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Hernández, A.; Covaleda, I. Sustainability and Creativity through Mail Art: A Case Study with Young Artists in Universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, M.; Jauk, E.; Kerschenbauer, K.; Anderwald, R.; Grond, L. Creating Art: An Experience Sampling Study in the Domain of Moving Image Art. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2017, 11, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastandrea, S.; Bartoli, G.; Carrus, G. The Automatic Aesthetic Evaluation of Different Art and Architectural Styles. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2011, 5, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Heo, S. Arts and Cultural Activities and Happiness: Evidence from Korea. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1637–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS; Talyor Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781138797031. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataswamy Reddy, M. Statistical Methods in Psychiatry Research and SPSS; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, Evaluation, and Interpretation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modelling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781609182304. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, P.J.; Beaty, R.E.; Nusbaum, E.C.; Eddington, K.M.; Levin-Aspenson, H.; Kwapil, T.R. Everyday Creativity in Daily Life: An Experience-Sampling Study of “Little c” Creativity. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2014, 8, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, E.R.; Devers, E.E.; McCrea, S.M. I Want to Be Creative: Exploring the Role of Hedonic Contingency Theory in the Positive Mood-Cognitive Flexibility Link. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, E.R.; McDonald, H.E.; Melton, R.J.; Harackiewicz, J.M. Processing Goals, Task Interest, and the Mood-Performance Relationship: A Mediational Analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.H.; Bull, R.; Adams, E.; Fraser, L. Positive Mood and Executive Function. Evidence From Stroop and Fluency Tasks. Emotion 2002, 2, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; Baas, M.; Nijstad, B.A. Hedonic Tone and Activation Level in the Mood-Creativity Link: Toward a Dual Pathway to Creativity Model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, G.E.; Lubart, T. Intelligence and Creativity: Mapping Constructs on the Space-Time Continuum. J. Intell. 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedek, M.; Jauk, E.; Sommer, M.; Arendasy, M.; Neubauer, A.C. Intelligence, Creativity, and Cognitive Control: The Common and Differential Involvement of Executive Functions in Intelligence and Creativity. Intelligence 2014, 46, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerlich, B.; Koteyko, N. Compounds, Creativity and Complexity in Climate Change Communication: The Case of “Carbon Indulgences". Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, D.R.; Towler, K.; Oliver, M.D.; Datta, S. An Examination of College Student Wellness: A Research and Liberal Arts Perspective. Health Psychol. Open 2017, 4, 2055102917719563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritze, J.G.; Blashki, G.A.; Burke, S.; Wiseman, J. Hope, Despair and Transformation: Climate Change and the Promotion of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2008, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Mireles-Acosta, J.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Happiness as Correlate of Sustainable Behavior: A Study of pro-Ecological, Frugal, Equitable and Altruistic Actions That Promote Subjective Wellbeing. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2011, 18, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspal, R.; Nerlich, B.; Cinnirella, M. Human Responses to Climate Change: Social Representation, Identity and Socio-Psychological Action. Environ. Commun. 2014, 8, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knebel, S.; Seele, P. Framing Sustainability in Public Procurement by Typologizing Sustainability Indicators—The Case of Switzerland. J. Public Procure. 2021, 21, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschner, R.; Ruppen, J.; Bornemann, B.; Emmenegger, R.; Sánchez, L.A. Mapping Sustainable Diets: A Comparison of Sustainability References in Dietary Guidelines of Swiss Food Governance Actors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C.H. Climate Friction: How Climate Change Communication Produces Resistance to Concern. Geogr. Res. 2022, 60, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, M.K.; Galway, L.; Buse, C.; Parkes, M.; Rees, E. Place-Based Climate Change Communication and Engagement in Canada’s Provincial North: Lessons Learned from Climate Champions. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, D. Bearing Witness? Polar Bears as Icons for Climate Change Communication in National Geographic. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.S.; Hase, V. Computational Methods for the Analysis of Climate Change Communication: Towards an Integrative and Reflexive Approach. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Clim. Chang. 2023, 14, e806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibeck, V.; Neset, T.S. Focus Groups and Serious Gaming in Climate Change Communication Research—A Methodological Review. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Clim. Chang. 2020, 11, e664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.K.; Seavey, J.R.; Mueller, R.C. Integrated Science and Art Education for Creative Climate Change Communication. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Kuskova, V.; Patzelt, H. Sustainable Development Survey Scale. APA PsycTests 2009, 30, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, P.; Argyle, M. Short Oxford Happiness Questionnaire—Short Scale; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2002; p. 8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsem, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babnik, K.; Benko, E.; von Humboldt, S. Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J.; Wigert, B.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Kaufman, J.C. Assessing Creativity with Self-Report Scales: A Review and Empirical Evaluation. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.C. Counting the Muses: Development of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS). Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M. Creative Mindsets: Measurement, Correlates, Consequences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2014, 8, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, T.S.; Silvia, P.J. Creative Days: A Daily Diary Study of Emotion, Personality, and Everyday Creativity. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2015, 9, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Male N | % | Female N | % | Total N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 672 | 50.1% | 669 | 50.1% | 1341 |

| Bulgaria | 1284 | 47.2% | 1434 | 47.2% | 2718 |

| Switzerland | 782 | 51.3% | 741 | 51.3% | 1523 |

| Czechia | 1079 | 43.6% | 1397 | 43.6% | 2476 |

| Estonia | 693 | 44.9% | 849 | 44.9% | 1542 |

| Finland | 780 | 49.5% | 797 | 49.5% | 1577 |

| France | 974 | 49.3% | 1003 | 49.3% | 1977 |

| United Kingdom | 506 | 44.0% | 643 | 44.0% | 1149 |

| Greece | 1335 | 47.7% | 1464 | 47.7% | 2799 |

| Croatia | 715 | 44.9% | 877 | 44.9% | 1592 |

| Hungary | 699 | 37.8% | 1150 | 37.8% | 1849 |

| Ireland | 840 | 47.5% | 930 | 47.5% | 1770 |

| Iceland | 435 | 48.2% | 468 | 48.2% | 903 |

| Italy | 1254 | 47.5% | 1386 | 47.5% | 2640 |

| Lithuania | 638 | 38.5% | 1021 | 38.5% | 1659 |

| Montenegro | 648 | 50.7% | 630 | 50.7% | 1278 |

| North Macedonia | 649 | 45.4% | 780 | 45.4% | 1429 |

| Netherlands | 750 | 51.0% | 720 | 51.0% | 1470 |

| Norway | 720 | 51.0% | 691 | 51.0% | 1411 |

| Portugal | 772 | 42.0% | 1066 | 42.0% | 1838 |

| Slovenia | 591 | 47.2% | 661 | 47.2% | 1252 |

| Slovakia | 647 | 45.6% | 771 | 45.6% | 1418 |

| Total | 17,463 | 46.4% | 20,148 | 46.4% | 37,611 |

| Country | Creative | Satisfied with Life as a Whole | Happy | Climate Change Causes | Feel Personally Responsible to Reduce Climate Change | Worried about Climate Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 4.5660 | 7.66 | 7.73 | 3.65 | 6.39 | 3.32 |

| ±1.14651 | ±1.685 | ±1.527 | ±2.145 | ±2.336 | ±0.940 | |

| Bulgaria | 4.3341 | 6.02 | 6.27 | 4.23 | 4.87 | 3.11 |

| ±1.34083 | ±2.440 | ±2.379 | ±6.683 | ±2.885 | ±0.930 | |

| Switzerland | 4.7951 | 8.30 | 8.09 | 3.73 | 7.28 | 3.32 |

| ±1.09894 | ±1.519 | ±1.488 | ±3.055 | ±1.991 | ±0.895 | |

| Czechia | 4.3566 | 7.10 | 6.91 | 4.50 | 4.35 | 3.15 |

| ±1.40678 | ±1.973 | ±1.997 | ±7.685 | ±2.887 | ±1.118 | |

| Estonia | 4.0162 | 7.45 | 7.50 | 3.48 | 5.53 | 2.99 |

| ±1.29106 | ±1.845 | ±1.742 | ±3.044 | ±2.871 | ±0.905 | |

| Finland | 4.3646 | 8.12 | 8.16 | 3.65 | 6.84 | 3.19 |

| ±1.27733 | ±1.505 | ±1.431 | ±1.981 | ±2.372 | ±0.838 | |

| France | 4.4305 | 7.02 | 7.44 | 3.69 | 7.49 | 3.28 |

| ±1.34539 | ±2.218 | ±1.705 | ±2.159 | ±2.060 | ±0.917 | |

| United Kingdom | 4.4578 | 7.08 | 7.29 | 3.74 | 7.11 | 3.33 |

| ±1.35482 | ±2.198 | ±1.988 | ±3.500 | ±2.327 | ±1.006 | |

| Greece | 4.5313 | 6.36 | 6.58 | 4.27 | 5.54 | 3.20 |

| ±1.33906 | ±1.746 | ±1.536 | ±5.376 | ±2.115 | ±0.935 | |

| Croatia | 4.3273 | 7.29 | 7.51 | 3.57 | 5.53 | 3.40 |

| ±1.44074 | ±2.237 | ±2.104 | ±2.024 | ±3.045 | ±1.024 | |

| Hungary | 4.4224 | 6.73 | 7.02 | 3.56 | 5.80 | 3.38 |

| ±1.22940 | ±2.104 | ±1.968 | ±2.543 | ±2.338 | ±0.783 | |

| Ireland | 4.4469 | 7.38 | 7.59 | 4.22 | 6.57 | 3.09 |

| ±1.29867 | ±1.907 | ±1.706 | ±6.843 | ±2.438 | ±0.991 | |

| Iceland | 4.3212 | 8.02 | 8.09 | 3.64 | 6.75 | 3.05 |

| ±1.36103 | ±1.703 | ±1.539 | ±1.895 | ±2.393 | ±0.947 | |

| Italy | 4.5640 | 6.96 | 7.05 | 4.08 | 5.91 | 3.24 |

| ±1.17592 | ±1.904 | ±1.669 | ±5.008 | ±2.411 | ±0.896 | |

| Lithuania | 4.1507 | 6.67 | 7.12 | 4.50 | 6.09 | 3.19 |

| ±1.53534 | ±2.417 | ±2.188 | ±7.801 | ±2.656 | ±0.974 | |

| Montenegro | 4.5524 | 6.94 | 7.57 | 3.91 | 4.07 | 3.09 |

| ±1.28237 | ±2.240 | ±2.017 | ±6.139 | ±2.669 | ±0.942 | |

| North Macedonia | 4.4262 | 6.40 | 6.65 | 3.82 | 4.28 | 3.31 |

| ±1.35128 | ±2.543 | ±2.351 | ±5.724 | ±2.988 | ±1.009 | |

| Netherlands | 4.5952 | 7.91 | 7.90 | 3.60 | 6.66 | 3.31 |

| ±1.10945 | ±1.410 | ±1.290 | ±.773 | ±2.042 | ±0.913 | |

| Norway | 4.3600 | 7.83 | 7.82 | 3.53 | 6.86 | 3.21 |

| ±1.22535 | ±1.707 | ±1.642 | ±1.560 | ±2.033 | ±0.855 | |

| Portugal | 4.3716 | 6.75 | 6.97 | 3.62 | 6.77 | 3.54 |

| ±1.20857 | ±2.099 | ±1.983 | ±2.299 | ±2.536 | ±0.851 | |

| Slovenia | 4.8379 | 7.65 | 7.69 | 3.44 | 6.42 | 3.49 |

| ±1.16094 | ±1.935 | ±1.748 | ±.750 | ±2.627 | ±0.871 | |

| Slovakia | 4.2687 | 6.26 | 6.54 | 5.35 | 5.02 | 2.85 |

| ±1.36408 | ±2.284 | ±2.050 | ±9.694 | ±2.538 | ±0.940 | |

| Total | 4.4296 | 7.08 | 7.24 | 3.94 | 5.94 | 3.23 |

| ±1.30711 | ±2.112 | ±1.934 | ±4.967 | ±2.683 | ±0.946 |

| Creative | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied with life as a whole | 0.111 ** | - | |||

| How happy are you | 0.122 ** | 0.689 ** | - | ||

| Climate change is caused by natural processes, human activity, or both | 0.021 ** | 0.021 ** | 0.017 ** | - | |

| To what extent feel a personal responsibility to reduce climate change | 0.104 ** | 0.149 ** | 0.159 ** | 0.245 ** | - |

| How worried about climate change | 0.100 ** | 0.017 ** | 0.027 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.430 ** |

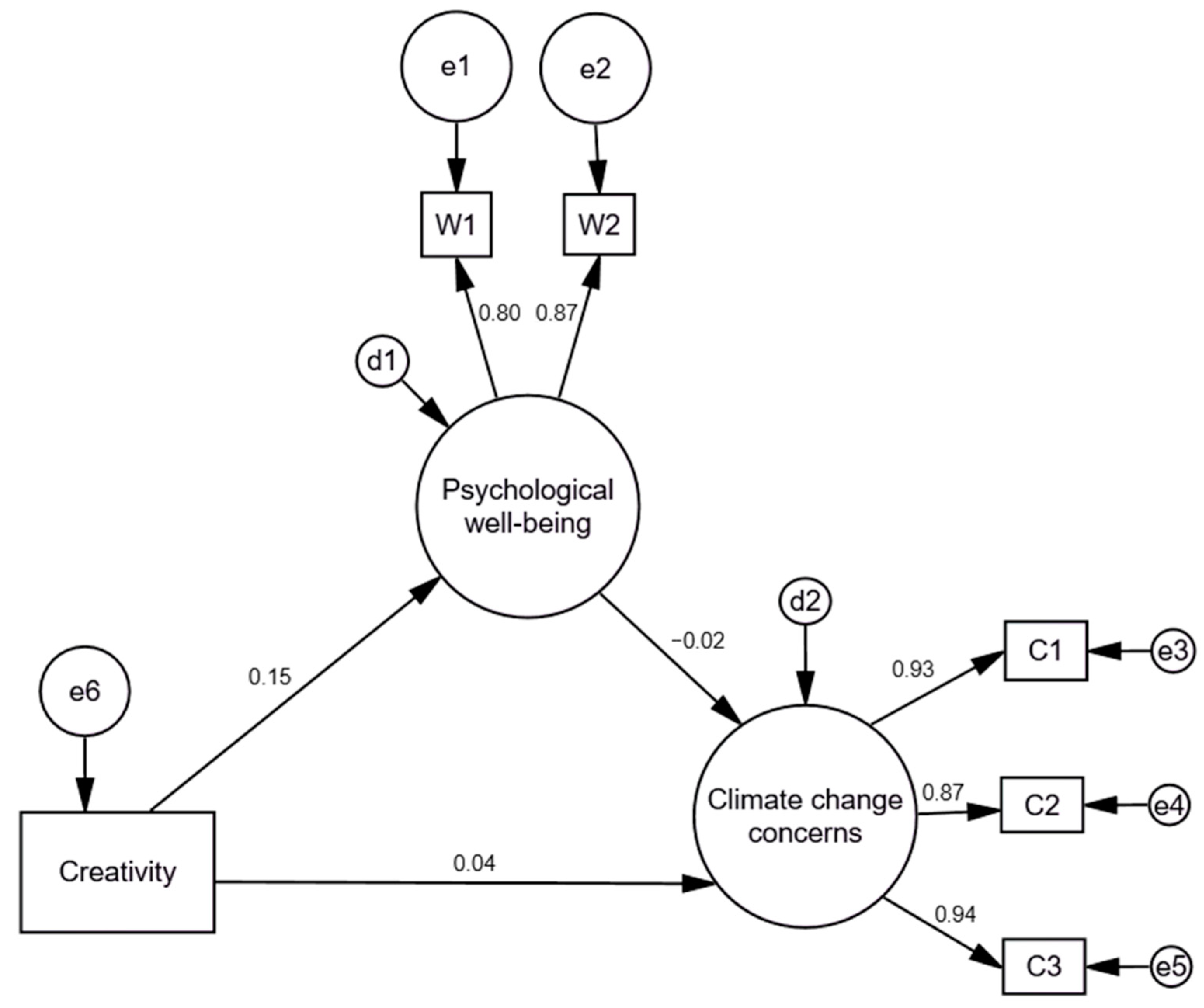

| Regression | B | S.E. | C.R. | p | β | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creativity | → | Psychological well-being | 0.191 | 0.008 | 23.087 | <0.001 | 0.149 |

| Psychological well-being | → | Climate change concerns | −0.022 | 0.006 | −3.572 | <0.001 | −0.021 |

| Creativity | → | Climate change concerns | 0.055 | 0.007 | 7.564 | <0.001 | 0.041 |

| Psychological well-being | → | B27 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.796 | ||

| Psychological well-being | → | C1 | 1.004 | 0.033 | 30.639 | <0.001 | 0.873 |

| Climate change concerns | → | C30 | 2.598 | 0.008 | 321.513 | 0.935 | |

| Climate change concerns | → | C31 | 2.187 | 0.008 | 269.625 | <0.001 | 0.872 |

| Climate change concerns | → | C32 | 1.000 | 0.944 | |||

| Logistic Parameter | Cluster 1 | Coeff. of Variation | Cluster 2 | Coeff. of Variation | t(35,450) | p | Mean Difference | Standard Error Difference | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||||||

| Climate change is caused by natural processes, human activity, or both | 3.430 | 0.887 | 0.259 | 3.498 | 0.818 | 0.234 | −6.948 | <0.001 | −0.068 | 0.010 | −0.081 |

| Feel a personal responsibility to reduce climate change | 5.356 | 2.725 | 0.509 | 6.249 | 2.582 | 0.413 | −29.073 | <0.001 | −0.894 | 0.031 | −0.341 |

| Worried about climate change | 3.203 | 0.964 | 0.301 | 3.266 | 0.928 | 0.284 | −5.746 | <0.001 | −0.063 | 0.011 | −0.067 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dirzyte, A.; Valatka, V. Creative and Happy Individuals Concerned about Climate Change: Evidence Based on the 10th Round of the European Social Survey in 22 Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215790

Dirzyte A, Valatka V. Creative and Happy Individuals Concerned about Climate Change: Evidence Based on the 10th Round of the European Social Survey in 22 Countries. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):15790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215790

Chicago/Turabian StyleDirzyte, Aiste, and Vytis Valatka. 2023. "Creative and Happy Individuals Concerned about Climate Change: Evidence Based on the 10th Round of the European Social Survey in 22 Countries" Sustainability 15, no. 22: 15790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215790

APA StyleDirzyte, A., & Valatka, V. (2023). Creative and Happy Individuals Concerned about Climate Change: Evidence Based on the 10th Round of the European Social Survey in 22 Countries. Sustainability, 15(22), 15790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215790

_Li.png)