Assessing the Venturing of Rural and Peri-Urban Youth into Micro- and Small-Sized Agricultural Enterprises in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Description of the Study

3.2. Sampling Procedure and Sample Size

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Analytical Analysis

3.6. Estimation and Likelihood Ratio Test

3.7. Data

4. Findings and Discussions

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Youth Involvement in Agriculture Enterprises

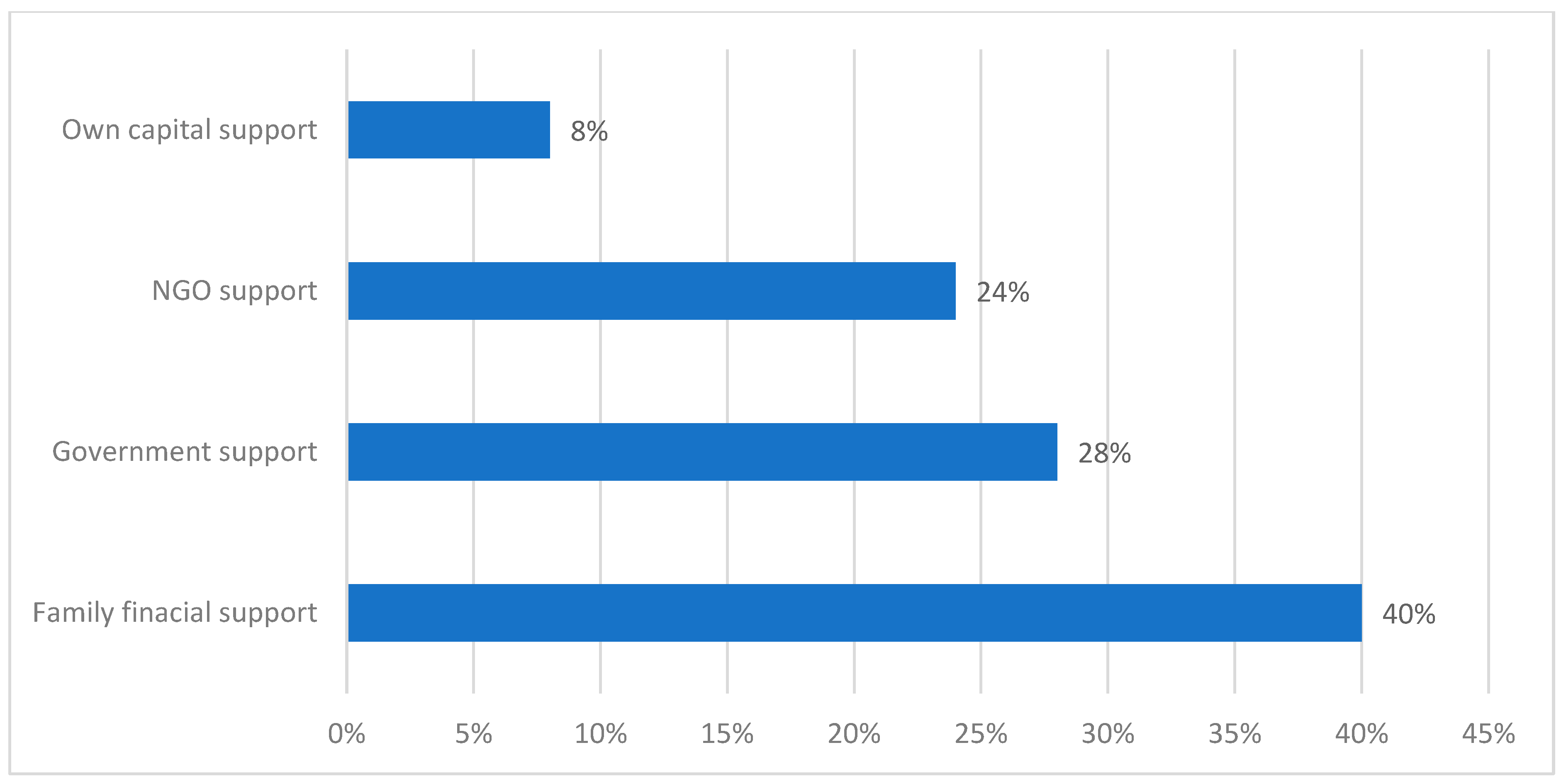

4.3. Source of Funding for Youth Engaged in Agricultural Enterprises

4.4. Contribution of Micro- and Small-Sized Agricultural Enterprises

4.5. Challenges Faced by Youth Engaged in Agricultural Enterprises

4.6. Determinants of Youth Venturing into Micro- and Small-Sized Agricultural Enterprises

4.7. Implication for Sustainable Development

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maisule, S.A.; Bamidele, J.; Sennuga, S.O. A Critical Review of Historical Analysis of Social Change in Nigeria from the Pre-Colonial to the Post-Colonial Period. Int. J. Art. Human. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutenje, M.J.; Farnworth, C.R.; Stirling, C.; Thierfelder, C.; Mupangwa, W.; Nyagumbo, I. A cost-benefit analysis of climate-smart agriculture options in Southern Africa: Balancing gender and technology. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 163, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, F.; Malik, M.; Miran, A. Psychological capital and stress: The mediating role of fear of COVID-19 in medical professionals of Pakistan. Multicult. Educ. 2021, 7, 624–631. [Google Scholar]

- Cheteni, P. Youth participation in agriculture in the Nkonkobe district municipality: South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 55, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, M.A.; Jiang, Y.; Acheampong, M.O. Capital and credit constraints in the engagement of youth in Ghanaian agriculture. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2019, 80, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauke, T.A.; Malatji, K.S. A Narrative Systematic Review of the Mental Toughness Programme Offered by the National Youth Development Agency. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2022, 1, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yami, M.; Feleke, S.; Abdoulaye, T.; Alene, A.; Bamba, Z.; Manyong, V. African rural youth engagement in agribusiness: Achievements, limitations, and lessons. Sustainability 2019, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramodum, A.; Chigada, J. Entrepreneurship and Management of Small Enterprises: An Overview of Agricultural Activities in the Mopani District Municipality. J. Entrep. Innov. 2021, 2, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wale, E.; Chipfupa, U. Entrepreneurship concepts/theories and smallholder agriculture: Insights from the literature with empirical evidence from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trans. R. Soc. S. Afr. 2021, 76, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endris, E.; Kassegn, A. The role of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to the sustainable development of sub-Saharan Africa and its challenges: A systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magagula, B.; Tsvakirai, C.Z. Youth perceptions of agriculture: Influence of cognitive processes on participation in agripreneurship. Dev. Pract. 2019, 30, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metelerkamp, L.; Drimie, S.; Biggs, R. We’re ready, the system’s not–youth perspectives on agricultural careers in South Africa. Agrekon 2019, 58, 154–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, J.I.F.; Matthews, N.; August, M.; Madende, P. Youths’ Perceptions and Aspiration towards Participating in the Agricultural Sector: A South African Case Study. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Chipfupa, U.; Tagwi, A. Youth’s participation in agriculture: A fallacy or achievable possibility? Evidence from rural South Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2021, 24, a4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, S.Ø.; Bulik, C.M.; Andreassen, O.A.; Rø, Ø.; Bang, L. The association between bullying and eating disorders: A case-control study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadebe, N. The Impact of Capital Endowment on Smallholder Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Drive-In Taking Advantage of Small-Scale Irrigation Schemes: Case Studies from Makhathini and Ndumo B Irrigation Schemes in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Master’s Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chipfupa, U.; Tagwi, A.; Wale, E. Psychological capital and climate change adaptation: Empirical evidence from smallholder farmers in South Africa. Jàmbá J. Dis. Ris. Stud. 2021, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wale, E.; Chipfupa, U.; Hadebe, N. Towards identifying enablers and inhibitors to on-farm entrepreneurship: Evidence from smallholders in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipfupa, U.; Wale, E. Farmer typology formulation accounting for psychological capital: Implications for on-farm entrepreneurial development. Dev. Pract. 2018, 28, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawire, A.W.; Wangia, S.M.; Okello, J.J. Determinants of use of information and communication technologies in agriculture: The case of Kenya agricultural commodity exchange in Bungoma County, Kenya. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 9, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Joshi, R.S.; Jagdale, S.S.; Bansode, S.B.; Shankar, S.S.; Tellis, M.B.; Pandya, V.K.; Chugh, A.; Giri, A.P.; Kulkarni, M.J. Discovery of potential multi-target-directed ligands by targeting host-specific SARS-CoV-2 structurally conserved main protease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 3099–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrong, R.; Kotu, B.H. Economic analysis of youth participation in agripreneurship in Benin. Heliyon 2022, 10, e08738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fola, G.M.; Alemu, T.; Tafesse, H. Determinants of Rural and Peri-Urban Youth Participation in Small and Micro Agricultural Enterprises in Southern Ethiopia; East African Scholars Publisher: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mthi, S.; Yawa, M.; Tokozwayo, S.; Ikusika, O.O.; Nyangiwe, N.; Thubela, T.; Tyasi, T.L.; Washaya, S.; Gxasheka, M.; Mpisana, Z.; et al. An Assessment of Youth Involvement in Agricultural Activities in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Agric. Sci. 2021, 12, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, L.O.; Baiyegunhi, L.J.S.; Mignouna, D.; Adeoti, R.; Dontsop-Nguezet, P.M.; Abdoulaye, T.; Manyong, V.; Bamba, Z.; Awotide, B.A. Impact of the youth-in-agribusiness program on employment creation in Nigeria. Sustainability 2022, 13, 7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, E.M.; Kleib, M.; Olson, J. Social media use for research participant recruitment: Integrative literature review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e38015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdoda, L.; Obi, A.; Ncoyini-Manciya, Z.; Christian, M.; Mayekiso, A. Assessment of profit efficiency for spinach production under small-scale irrigated agriculture in the eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibane, Z.; Soni, S.; Phali, L.; Mdoda, L. Factors impacting sugarcane production by small-scale farmers in KwaZulu-Natal Province-South Africa. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, P.W.G.S.L.; Niranjala, S.A.U. Factors affecting youth Participation in Agriculture in Galenbidunuwewa divisional secretariat division, Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. J. Rajarata Econ. Rev. 2021, 1, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, M.; Houngbedji, K.; Kondylis, F.; O’Sullivan, M.; Selod, H. Securing Property Rights for Women and Men in Rural Benin; Gender Innovation Lab Policy Brief No. 14. World Bank: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25453 (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Magesa, M.M.; Michael, K.; Ko, J. Access and use of agricultural market information by smallholder farmers: Measuring informational capabilities. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 86, e12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng’atigwa, A.A.; Hepelwa, A.; Yami, M.; Manyong, V. Assessment of factors influencing youth involvement in horticulture agribusiness in Tanzania: A case study of Njombe Region. Agriculture 2020, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosec, K.; Ghebru, H.; Holtemeyer, B.; Mueller, V.; Schmidt, E. The effect of land access on youth employment and migration decisions: Evidence from rural Ethiopia. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 100, 931–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasakin, I.J.; Ogunniyi, A.I.; Bello, L.O.; Mignouna, D.; Adeoti, R.; Bamba, Z. Impact of intensive youth participation in agriculture on rural households’ revenue: Evidence from rice farming households in Nigeria. Agriculture 2022, 12, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mare, F.; Bahta, Y.T.; Van Niekerk, W. The impact of drought on commercial livestock farmers in South Africa. Dev. Pract. 2018, 28, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Measuring Type | Expected Priori |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | The sex of the youth farmer (male/female) | Dummy | +/− |

| Age | Age of the farmer in years | Continuous | +/− |

| Family size | Number of the family household of the farmer | Continuous | + |

| Farm size | Land area under cultivation by the farmer | Continuous | + |

| Occupation | Is farming the main occupation for the farm (self-employed, employed by the government)? | Dummy | +/− |

| Education | Number of years spent in school by the farmer | Continuous | + |

| Marital status | The marriage status of the farmer (married/single/window) | Dummy | +/− |

| Household monthly income | This is the household monthly income in ZAR (farm income, grants, and remittances) | Continuous | + |

| Mode of acquisition of land | The mode of acquisition | Dummy | + |

| Total labour intensity | Number of persons employed | Continuous | + |

| Family labour intensity | Family members working per unit of land cultivated | Continuous | + |

| Input used | The agronomic practices used by the farmer | Dummy | + |

| Total revenue | Total amount realized from sales of output | Continuous | + |

| Total variable costs | Total amount from the inputs used in the farm | Continuous | + |

| Value of output | Market value of physical agricultural output | Continuous | |

| Access to extension | Frequency visits of extension agents | Continuous | + |

| Access to credit | Availability of accessible credit (yes/no) | Dummy | +/− |

| Member of farm organization | Is the farmer a member of a farm organization? | Dummy | + |

| Variable | Participating in Agricultural Enterprises (n = 73) | Non-Participating in Agricultural Enterprises (n = 47) | Overall (n = 120) | t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.003 *** |

| Occupation (Sslf-employed) | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.321 | |

| Access to extension services (Yes) | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.143 |

| Member of farm organization (Yes) | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.028 ** |

| Engaged in non-agricultural enterprises | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.401 |

| Access to credit (Yes) | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.005 *** |

| Variable | Participating in Agricultural Enterprises (n = 73) | Non-Participating in Agricultural Enterprises (n = 47) | Overall (n = 127) | Chi-Square |

| Age (years) | 32.13 | 32.01 | 32.07 | 0.015 ** |

| Family size (count) | 3.54 | 2.13 | 3.34 | 0.021 ** |

| Farm size (Ha) | 2.24 | 0.01 | 1.13 | 0.165 |

| Years spent in school (years) | 13.43 | 11.65 | 12.54 | 0.007 *** |

| Distanced travelled to market center (kilometers) | 14.30 | 14.21 | 14.25 | 0.002 *** |

| Household monthly income (ZAR) | 1547.12 | 3 458.79 | 2 502.96 | 0.004 *** |

| Variable | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in agriculture | Older farmers (36 years and above) | 0.72 |

| Young farmers | 0.28 | |

| Participating in agricultural enterprises by youth | Yes No | 0.28 0.58 |

| Type of enterprise | Vegetable enterprise | 30 |

| Crop enterprise | 24 | |

| Poultry enterprise | 16 | |

| Cattle, sheep enterprise | 15 | |

| Do youth participate in decision-making in the enterprise? | Yes No | 72 28 |

| Variable | Β | P > z | Marginal Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 0.643 | 0.013 ** | 0.38 |

| Age | 0.852 | 0.005 *** | 0.24 |

| Access to credit | −0.549 | 0.015 ** | −0.43 |

| Years spent in school | 0.956 | 0.009 *** | 0.52 |

| Farm size | 0.869 | 0.002 *** | 0.33 |

| Member of farm organization | 0.737 | 0.047 ** | 0.46 |

| Access to extension services | −0.480 | 0.032 ** | −0.54 |

| Distance to market centers | −0.689 | 0.013 ** | −0.56 |

| Number of observations = 120 | LR chi2 (9) = 129.67, Pr > Chi2 = 0.000 | Log likelihood = −117.52 | Pseudo R2 = 0.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thibane, Z.; Mdoda, L.; Gidi, L.; Mayekiso, A. Assessing the Venturing of Rural and Peri-Urban Youth into Micro- and Small-Sized Agricultural Enterprises in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115469

Thibane Z, Mdoda L, Gidi L, Mayekiso A. Assessing the Venturing of Rural and Peri-Urban Youth into Micro- and Small-Sized Agricultural Enterprises in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115469

Chicago/Turabian StyleThibane, Zimi, Lelethu Mdoda, Lungile Gidi, and Anele Mayekiso. 2023. "Assessing the Venturing of Rural and Peri-Urban Youth into Micro- and Small-Sized Agricultural Enterprises in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115469

APA StyleThibane, Z., Mdoda, L., Gidi, L., & Mayekiso, A. (2023). Assessing the Venturing of Rural and Peri-Urban Youth into Micro- and Small-Sized Agricultural Enterprises in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability, 15(21), 15469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115469