The Impacts of Ecotourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Perceived Values on Their Behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

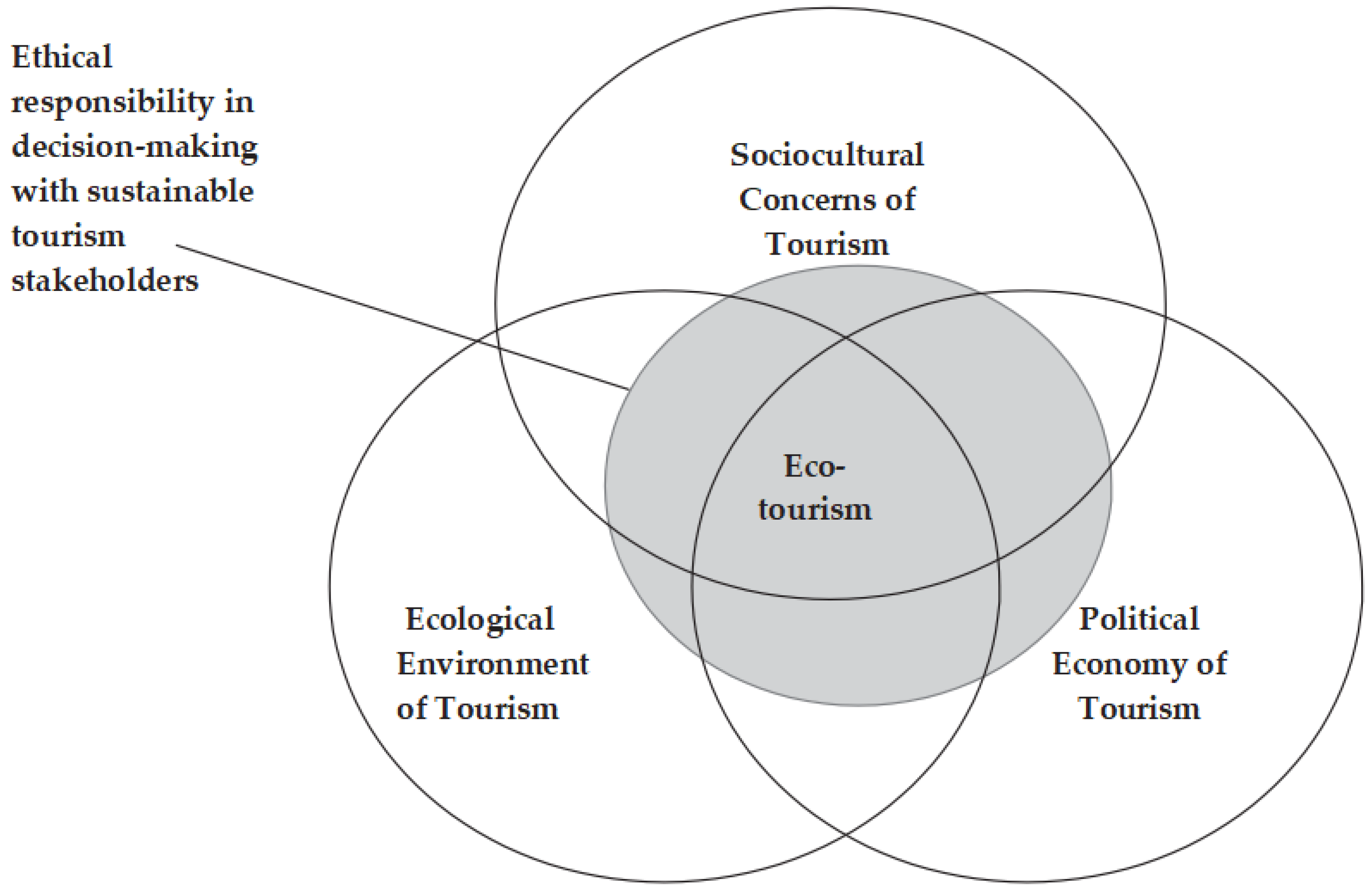

2.1. Ecotourism

2.2. Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity

2.3. Tourists’ Perceived Value

2.4. Tourists’ Behavior Intention

2.5. Environmentally Responsible Behavior

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. The Relationship between Perceived Authenticity and Perceived Value in Ecotourism

3.2. The Relationship between Perceived Authenticity and Revisit Intentions and Environmentally Responsible Behaviors in Ecotourism

3.3. The Relationship between Perceived Values and Revisit Intentions in Ecotourism

3.4. The Relationship between Perceived Values and Environmentally Responsible Behaviors in Ecotourism

4. Questionnaire Development

5. Data Collection

6. Demographic Profile

7. Reliability Analysis

8. Scale Verification by Confirmatory fa8. Scale Verification by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

9. Structure Equation Model (SEM)

10. Results and Discussion

11. Theoretical Contribution

12. Practical Implications

13. Research Limitation and Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osman, T.; Shaw, D.; Kenawy, E. Examining the extent to which stakeholder collaboration during ecotourism planning processes could be applied within an Egyptian context. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C.; Buckley, R.; Shakeela, A.; Castley, J.G. Ecotourism’s contributions to conservation: Analysing patterns in published studies. J. Ecotour. 2021, 20, 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A. Does ecotourism contribute to sustainable destination development, or is it just a marketing hoax? Analyzing twenty-five years contested journey of ecotourism through a meta-analysis of tourism journal publications. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 1047–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, D. The Concept of Ecotourism: Evolution and Trends. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 2, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanra, S.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Bibliometric analysis and literature review of ecotourism: Toward sustainable development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Sibi, P.S.; Sharma, P. Journal of ecotourism: A bibliometric analysis. J. Ecotourism 2022, 21, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. Ecotourism, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Milton, QLD, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Makoni, T.; Mazuruse, G.; Nyagadza, B. International tourist arrivals modelling and forecasting: A case of Zimbabwe. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2023, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martín, J.M.; Salinas Fernández, J.A. The effects of technological improvements in the train network on tourism sustainability. An approach focused on seasonality. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.M.G.; Martín, J.M.M.; del Sol Ostos Rey, M. An analysis of the changes in the seasonal patterns of tourist behavior during a process of economic recovery. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2020, 161, 120280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipinos, G.; Fokiali, P. An assessment of the attitudes of the inhabitants of Northern Karpathos, Greece: Towards a framework for ecotourism development in environmentally sensitive areas: An ecotourism framework in environmentally sensitive areas. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 11, 655–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatma Indra Jaya, P.; Izudin, A.; Aditya, R. The role of ecotourism in developing local communities in Indonesia. J. Ecotourism 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A. Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso, A.H.; Dahles, H. A community perspective on local ecotourism development: Lessons from Komodo National Park. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonn, P.; Mizoue, N.; Ota, T.; Kajisa, T.; Yoshida, S. Evaluating the Contribution of Community-based Ecotourism (CBET) to Household Income and Livelihood Changes: A Case Study of the Chambok CBET Program in Cambodia. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 151, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaano, A.I. Potential of ecotourism as a mechanism to buoy community livelihoods: The case of Musina Municipality, Limpopo, South Africa. J. Bus. Soc. Eco. Dev. 2021, 1, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey, M. Setting standards: Certification programmes for ecotourism and sustainable tourism. In Ecotourism and Conservation in the Americas; Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 234–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. Is ecotourism sustainable? Environ. Manag. 1997, 21, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, T.; Bulut, U. Is tourism an engine for economic recovery? Theory and empirical evidence. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, A.; Moslehpour, M.; Qiu, R.; Lin, P.-K.; Ismail, T.; Rahman, F.F. The impact of eco-innovation, ecotourism policy and social media on sustainable tourism development: Evidence from the tourism sector of Indonesia. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraž. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.E.; Hardner, J.; Stewart, M. Ecotourism and economic growth in the Galapagos: An island economy-wide analysis. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2009, 14, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.H. Principles of ecotourism development. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2002, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Liu, Y.C. Deconstructing the internal structure of perceived authenticity for heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2134–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Oh, C.O.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. Assessing the economic values of World Heritage Sites and the effects of perceived authenticity on their values. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberghien, G.; Bremner, H.; Milne, S. Performance and visitors’ perception of authenticity in eco-cultural tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandza, B.I. Tourist perceived value, relationship to satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: The example of the Croatian tourist destination Dubrovnik. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gu, Y.; Cen, J. Festival tourists’ emotion, perceived value, and behavioral intentions: A test of the moderating effect of festivalscape. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2011, 12, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Lu, C.C. Destination image, novelty, hedonics, perceived value, and revisiting behavioral intention for island tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Lee, S.K.; Ahn, Y.J.; Kiatkawsin, K. Tourist-perceived quality and loyalty intentions towards rural tourism in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Santini, F.; Ladeira, W.J.; Sampaio, C.H. Tourists’ perceived value and destination revisit intentions: The moderating effect of domain—Specific innovativeness. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Moscardo, G. Understanding the impact of ecotourism resort experiences on tourists’ environmental attitudes and behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handriana, T.; Ambara, R. Responsible environmental behavior intention of travelers on ecotourism sites. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 22, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstetter, D.L.; Hou, J.S.; Lin, C.H. Profiling Taiwanese ecotourists using a behavioral approach. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, C. Are backpackers ethical tourists? In Backpacker Tourism: Concepts and Profifiles; Hannam, K., Ateljevic, I., Eds.; Chanel View: Clevedon, UK, 2008; pp. 54–81. [Google Scholar]

- Beall, J.M.; Boley, B.B.; Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M. What drives ecotourism: Environmental values or symbolic conspicuous consumption? J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1215–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Ecotourism Society (TIES). TIES Announces Ecotourism Principles Revision. Available online: https://ecotourism.org/news/ties-announces-ecotourism-principles-revision/ (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Fennell, D.A. Ecotourism, 5th ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Muhanna, E. Sustainable tourism development and environmental management for developing countries. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2006, 4, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, M.Z.A.; Wang, G.; Wu, J.; Cao, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, T. Dependable structural health monitoring using wireless sensor networks. IEEE Trans. Depend. Secure 2015, 14, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosammam, H.M.; Sarrafi, M.; Nia, J.T.; Heidari, S. Typology of the ecotourism development approach and an evaluation from the sustainability view: The case of Mazandaran Province, Iran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, E. Ecotourism in the third world: Problems for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Chatterjee, B. Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, A.; Kondolf, G.M. How Eco is Eco-Tourism? A Systematic Assessment of Resorts on the Red Sea, Egypt. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.A.; Durham, W.H.; Driscoll, L.; Honey, M. Can ecotourism deliver real economic, social, and environmental benefits? A study of the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, Z.A. The impact of ecotourism on livelihood and natural resource management in Eselenkei, Amboseli Ecosystem, Kenya. Land Degrad. Dev. 2002, 13, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, H.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, C.-K. A moderator of destination social responsibility for tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors in the VIP model. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carrascosa-López, C.; Carvache-Franco, W. The Perceived Value and Future Behavioral Intentions in Ecotourism: A Study in the Mediterranean Natural Parks from Spain. Land 2021, 10, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Phau, I.; Hughes, M.; Li, Y.F.; Quintal, V. Heritage Tourism in Singapore Chinatown: A Perceived Value Approach to Authenticity and Satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. Extending the theory of planned behaviour: Testing the effects of authentic perception and environmental concerns on the slow-tourist decision-making process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, F.; Soutar, G.N. Experiences, post-trip destination image, satisfaction and loyalty: A study in an ecotourism context. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-S. The Moderating Role of Intercultural Service Encounters in the Relationship among Tourist’s Destination Image, Perceived Value and Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. Am. J. Tour. Manag. 2018, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wei, C.; Nie, L. Experiencing authenticity to environmentally responsible behavior: Assessing the effects of perceived value, tourist emotion, and recollection on industrial heritage tourism. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The past and future of ‘symbolic interactionism’. Semiotica 1976, 16, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, D.; Tomadin, A.; Manzoni, C.; Kim, Y.J.; Lombardo, A.; Milana, S.; Polini, M. Ultrafast collinear scattering and carrier multiplication in graphene. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casteran, H.; Roederer, C. Does authenticity really affect behavior? The case of the Strasbourg Christmas Market. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A. Contemporary South Africa; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Lin, V.S.; Jin, W.; Luo, Q. The authenticity of heritage sites, tourists’ quest for existential authenticity, and destination loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C. The willingness of heritage tourists to pay for perceived authenticity in Pingxi, Taiwan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1044–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondnejad, A. Tourist loyalty to a local cultural event: The case of turkmen handicrafts festival. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M.S. The effects of perceived authenticity, information search behaviour, motivation and destination imagery on cultural behavioural intentions of tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner-Velazquez, B.; Fuentes-Blasco, M.; Gil-Saura, I. Value antecedents in relationship between tourism companies. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.; Callarisa, L.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Moliner, M.A. Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M.S. Experience value: Antecedents and consequences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 910–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.; Fang, Y.H.; Huang, H.Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inform. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Thapa, B. Perceived value and flow experience: Application in a nature-based tourism context. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The distinction between desires and intentions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, L.T.I.; So, A.S.I.; Lo, I.S.; Fong, L.H.N. Does the quality of tourist shuttles influence revisit intention through destination image and satisfaction? The case of Macao. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 32, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Lieana-Cabanillas, F.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Buhalis, D. DMO online platforms: Image and intention to visit. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D.; Han, H. Investigating the key factors affecting behavioral intentions: Evidence from a full—Service restaurant setting. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 23, 1000–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H. Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som, A.P.M.; Marzuki, A.; Yousefi, M. Factors influencing visitors’ revisit behavioral intentions: A case study of Sabah, Malaysia. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2012, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Liu, C.H.S. Moderating and mediating roles of environmental concern and ecotourism experience for revisit intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1854–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Lawton, L.J.; Weaver, D.B. Evidence for a South Korean model of ecotourism. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiletu, C.; Jiang, L. Study on the Sustainable Development Strategy of Ecotourism Scenic Spots. In Proceedings of the 2017 7th International Conference on Social science and Education Research (SSER2017), Xi’an, China, 3–5 November 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivek, D.J.; Hungerford, H. Predictors of responsible behavior in members of three Wisconsin conservation organizations. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 21, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Rathouse, K.; Scarles, C.; Holmes, K.; Tribe, J. Public understanding of sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerden, M.D.; Witt, P.A. The impact of direct and indirect experiences on the development of environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Kim, H.J.; Liang, M.; Ryu, K. Interrelationships between tourist involvement, tourist experience, and environmentally responsible behavior: A case study of Nansha Wetland Park, China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafyri, A.; Hovardas, T.; Poirazidis, K. Determinants of visitor pro-environmental intentions on two small Greek islands: Is ecotourism possible at coastal protected areas? Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-N.; Li, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-H.; Ruan, W.-Q. How does authenticity enhance flow experience through perceived value and involvement: The moderating roles of innovation and cultural identity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Phau, I. Young tourists’ perceptions of authenticity, perceived value and satisfaction: The case of Little India, Singapore. Young Consum. 2018, 19, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, A. The convergence process in heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Understanding repurchase intention of Airbnb consumers: Perceived authenticity, electronic word-of-mouth, and price sensitivity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chao, R.F. How experiential consumption moderates the effects of souvenir authenticity on behavioral intention through perceived value. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.; Knutson, B.J. An argument for providing authenticity and familiarity in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2004, 11, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Student motivations: A heritage tourism perspective. Anatolia 2010, 21, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, Z.M.; Othman, N.; Ahmad, K.N. The role of perceived authenticity as the determinant to revisit heritage tourism destination in Penang. Theor. Pract. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpi, D.; Mason, M.; Raggiotto, F. To Rome with love: A moderated mediation model in Roman heritage consumption. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.S.; McKercher, B. Managing heritage resources as tourism products. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 9, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Managing heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 682–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martín, J.; Guaita Martínez, J.; Molina Moreno, V.; Sartal Rodríguez, A. An Analysis of the Tourist Mobility in the Island of Lanzarote: Car Rental Versus More Sustainable Transportation Alternatives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C.; Huang, L.-M. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azinuddin, M.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Mior Shariffuddin, N.S.; Kamarudin, M.K.A.; Mat Som, A.P. An exploration of perceived ecotourism design affordance and destination social responsibility linkages to tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour and destination loyalty. J. Ecotourism 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budruk, M.; White, D.D.; Wodrich, J.A.; Van Riper, C.J. Connecting Visitors to People and Place: Visitors’ Perceptions of Authenticity at Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona. J. Herit. Tour. 2008, 3, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Kumar, V.; Syan, A.S.; Parmar, Y. Role of green advertisement authenticity in determining customers’ pro--environmental behavior. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2021, 126, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, T.F.T. Assessing the Effects of Perceived Value on Event Satisfaction, Event Attachment, and Revisit Intentions in Wine Cultural Event at Yibin International Exhibition Center, Southwest China. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2020, 7, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.L.; Backman, K.F.; Huang, Y.C. Creative tourism: A preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, perceived value and revisit intention. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 8, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hu, D.; Swanson, S.R.; Su, L.; Chen, X. Destination perceptions, relationship quality, and tourist environmentally responsible behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Cheung, C. Chinese heritage tourists to heritage sites: What are the effects of heritage motivation and perceived authenticity on satisfaction? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, P. Testing the structural relationships of tourism authenticities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Fernandez, R.; Iniesta-Bonillo, M.A. The concept of perceived value: A systematic review of the research. Mark. Theory 2007, 7, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Siddiquei, A.N.; Awan, H.M.; Bukhari, K. Relationship between service quality, perceived value, satisfaction and revisit intention in hotel industry. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2012, 4, 788–805. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, S.A.; Othman, N.A.; Muhammad, N.M.N. Tourist perceived value in a community-based homestay visit: An investigation into the functional and experiential aspect of value. J. Vacat. Mark. 2011, 17, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. Development of a multi-dimensional scale for measuring the perceived value of a service. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, P.; Vlosky, R. How previous visits shape trip quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and future behavioral intentions: The case of forest-based ecotourism in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Sport Manag. Rec. Tour. 2013, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lapira, E.; Bagheri, B.; Kao, H.A. Recent advances and trends in predictive manufacturing systems in big data environment. Manuf. Lett. 2013, 1, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Satchabut, T. Factors affecting behavioral intentions and responsible environmental behaviors of Chinese tourists: A case study in Bangkok, Thailand. UTCC Int. J. Bus. Econ. 2017, 9, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equation Program Manual; BMDP Statistical Software Encino: Los Angeles, CA, USA; Cork, Ireland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basis Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.K. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Ye, B.J. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.; Adele, D. Gender and Mountaineering Tourism. In Mountaineering Tourism, 1st ed.; Ghazali, M., James, H., Anna, T.C., Eds.; Routledge: Londan, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie-Mohr, D.; Nemiroff, L.S.; Beers, L.; Desmarais, S. Determinants of responsible environmental behavior. J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G. Consuming heritage: Perceived historical authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 835–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.D.; Li, A.N.; Lv, W.B.; Chen, G.Y.; Yang, C.W. A Study on the Precedent Variables of the Environmental Responsible Behavior of the Heritage Tourists: From the perspectives of authenticity, nostalgia and place attachment. J. Outdoor Rec. Stud. 2014, 27, 59–91. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H. Responsible Tourism: Using Tourism for Sustainable Development, 2nd ed.; Goodfellow Pub Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock, B.; Lovelock, K. The Ethics of Tourism: Critical and Applied Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, W. Promoting ecotourism through networks: Case studies in the Balearic Islands. J. Ecotourism 2009, 8, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd-Shahwahid, H.O.; Mohd-Iqbal, M.N.; Amiramas-Ayu, A.M.; Rahinah, I.; Mohd-Ihsan, M.S. Social Network Analysis of mpung Kuantan Fireflies Park, Selangor and the Implications Upon its Governance. J. Trop. For. Sci. 2016, 28, 490–497. [Google Scholar]

- Pasape, L.; Anderson, W.; Lindi, G. Towards Sustainable Ecotourism through Stakeholder Collaborations in Tanzania. J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A.; Tolkach, D.; King, B. Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondino, E.; Beery, T. Ecotourism as a learning tool for sustainable development. The case of Monviso Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, Italy. J. Ecotourism 2019, 18, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|

| Perceived authenticity | 0.904 |

| Perceived value | 0.914 |

| Monetary value | 0.812 |

| Quality value | 0.898 |

| Emotional value | 0.854 |

| Social value | 0.842 |

| Revisit intention | 0.809 |

| Environmentally responsible behaviors | 0.869 |

| Item | Corrected Item–Total Correlation (CITC) |

|---|---|

| Perceived authenticity | |

| PA1 | 0.738 |

| PA2 | 0.807 |

| PA3 | 0.777 |

| PA4 | 0.727 |

| PA5 | 0.660 |

| PA6 | 0.707 |

| Monetary value | |

| PVM1 | 0.541 |

| PVM2 | 0.571 |

| PVM3 | 0.544 |

| Quality value | |

| PQ1 | 0.722 |

| PQ2 | 0.643 |

| PQ3 | 0.648 |

| PQ4 | 0.703 |

| PQ5 | 0.672 |

| Emotional value | |

| EV1 | 0.550 |

| EV2 | 0.595 |

| EV3 | 0.586 |

| EV4 | 0.606 |

| Social value | |

| SV1 | 0.584 |

| SV2 | 0.633 |

| SV3 | 0.624 |

| Revisit intention | |

| RI1 | 0.590 |

| RI2 | 0.726 |

| RI3 | 0.662 |

| Environmentally responsible behaviors | |

| ERB1 | 0.645 |

| ERB2 | 0.811 |

| ERB1 | 0.718 |

| ERB4 | 0.707 |

| Variables | Factor Loadings | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monetary value | 0.700 | 0.594 | 0.814 |

| Quality value | 0.820 | 0.644 | 0.900 |

| Emotional value | 0.710 | 0.597 | 0.855 |

| Social value | 0.770 | 0.646 | 0.845 |

| Social Value | Emotional Value | Quality Value | Monetary Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social value | 0.621 | |||

| Emotional value | 0.111 | 0.397 | ||

| Quality value | 0.125 | 0.129 | 0.799 | |

| Monetary value | 0.150 | 0.097 | 0.233 | 0.663 |

| AVE | 0.557 | 0.517 | 0.648 | 0.518 |

| Standard Estimates (>0) | S.E. | C.R. | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived authenticity | → | Perceived value | 0.211 | 0.072 | 2.948 | *** |

| Perceived value | → | Revisit intention | 0.413 | 0.141 | 2.918 | *** |

| Perceived authenticity | → | Revisit intention | 0.303 | 0.106 | 2.870 | *** |

| Perceived value | → | Environmentally responsible behaviors | 0.586 | 0.143 | 4.092 | *** |

| Perceived authenticity | → | Environmentally responsible behaviors | 0.297 | 0.107 | 2.781 | *** |

| Item | Total Effect (c) | Mesomeric Effect (a*b) | Direct Effect (c’) | 95% BootCI | Calculation Formula of Effect Proportion | Proportion of Effects | Inspection Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived authenticity =〉 Perceived value =〉 Environmentally responsible behaviors | 0.454 | 0.126 | 0.328 | 0.087~0.165 | a*b/c | 27.801% | Partial mediation |

| Perceived authenticity =〉Perceived value =〉 Revisit intention | 0.462 | 0.144 | 0.318 | 0.097~0.175 | a*b/c | 31.143% | Partial mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Hu, X.; Lee, H.M.; Zhang, Y. The Impacts of Ecotourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Perceived Values on Their Behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021551

Yang L, Hu X, Lee HM, Zhang Y. The Impacts of Ecotourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Perceived Values on Their Behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021551

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lu, Xiao Hu, Hoffer M. Lee, and Yuqing Zhang. 2023. "The Impacts of Ecotourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Perceived Values on Their Behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021551

APA StyleYang, L., Hu, X., Lee, H. M., & Zhang, Y. (2023). The Impacts of Ecotourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Perceived Values on Their Behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site. Sustainability, 15(2), 1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021551