Cultural Space as Sustainability Indicator for Development Planning (Case Study in Jakarta Coastal Area)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

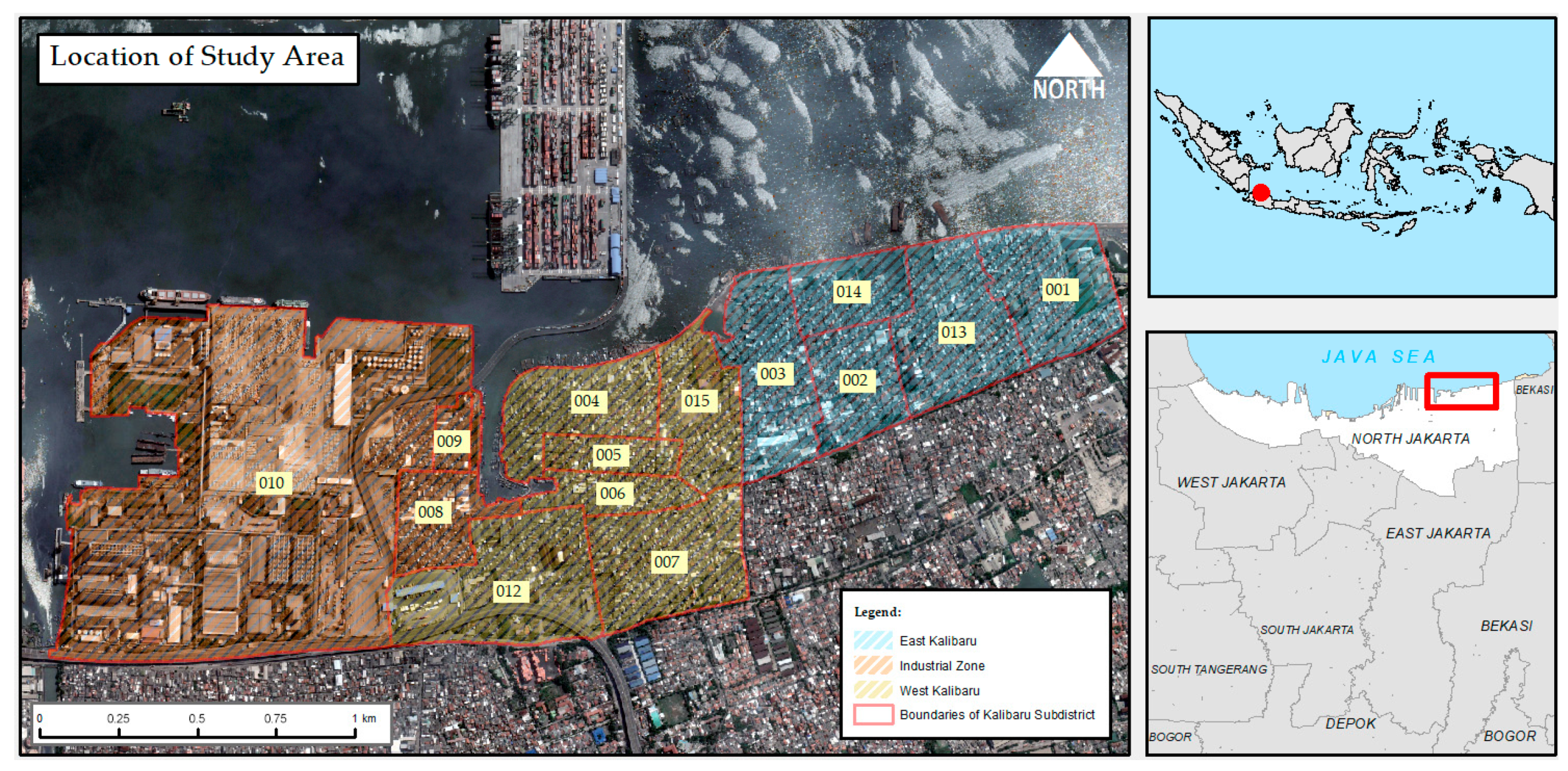

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Approach

3. Results

3.1. Regional Conditions

3.2. Cultural Spaces

3.2.1. Core Cultural Spaces

3.2.2. Tactical Cultural Spaces

3.2.3. Cultural Spaces of Conflict

3.2.4. Cultural Transformation

4. Discussion

4.1. Development and Transformation of Cultural Spaces

4.2. Policy Implication of Cultural Spaces in the CDI

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boyle, J. Cultural influences on implementing environmental impact assessment: Insights from Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1998, 18, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.; Joas, M.; Sundback, S.; Theobald, K. Governing local sustainability. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2006, 49, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukmana, D. The Change and Transformation of Indonesian Spatial Planning after Suharto’s New Order Regime: The Case of the Jakarta Metropolitan Area. Int. Plan. Stud. 2015, 20, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, C. Spatial Planning for Sustainable Development: An Action Planning Approach for Jakarta. J. Perenc. Wil. Dan Kota 2014, 25, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, P.; Birnie, A. Is there a correct way of establishing sustainability indicators? The case of sustainability indicator development on the Island of Guernsey. Local Environ. 2005, 10, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.D.G.; Dougill, A.J.; Mabee, W.E.; Reed, M.; McAlpine, P. Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, C. Re-thinking Sustainability Indicators: Local Perspectives of Urban Sustainability. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Sinha, R.; Koradia, D.; Patel, R.; Parmar, M.; Rohit, P.; Patel, H.; Patel, K.; Chand, V.S.; James, T.J.; et al. Mobilizing grassroots’ technological innovations and traditional knowledge, values and institutions: Articulating social and ethical capital. Futures 2003, 35, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewitt, J. Understanding Sustainable Development; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P.; Jalal, K.; Boyd, J. An Introduction to Sustainable Development; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, T.B. Sustainability assessment: Exploring the frontiers and paradigms of indicator approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizdaroglu, D. The role of indicator-based sustainability assessment in policy and the decision-making process: A review and outlook. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myllyviita, T.; Lähtinen, K.; Hujala, T.; Leskinen, L.A.; Sikanen, L.; Leskinen, P. Identifying and rating cultural sustainability indicators: A case study of wood-based bioenergy systems in eastern Finland. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 16, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, R.; Angelstam, P.; Degerman, E.; Teitelbaum, S.; Andersson, K.; Elbakidze, M.; Drotz, M.K. Social and cultural sustainability: Criteria, indicators, verifier variables for measurement and maps for visualization to support planning. Ambio 2013, 42, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahtinen, K.; Myllyviita, T. Cultural sustainability in reference to the global reporting initiative (GRI) guidelines. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 5, 290–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P. Assessing Cultural Sustainability; United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Setyowati, E.; Nursyamsi, F.; Argama, R.; Rofiandri, R.; Safira, R.; Ninditya, R.; Gumay, H. Belajar Advokasi Kebijakan Seni; Koalisi Seni: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bappeda DKI Jakarta. Rencana Pembangunan Daerah 2023–2026; Bappeda DKI Jakarta: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sudaryono, S. Paradigma Lokalisme Dalam Perencanaan Spasial. J. Reg. City Plan. 2006, 17, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, R.; Masron, I.N. Jakarta: A city of cities. Cities 2020, 106, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusno, A. Runaway city: Jakarta Bay, the pioneer and the last frontier. Inter-Asia Cult. Stud. 2011, 12, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlambang, S.; Leitner, H.; Tjung, L.J.; Sheppard, E.; Anguelov, D. Jakarta’s great land transformation: Hybrid neoliberalisation and informality. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudalah, D.; Firman, T. Beyond property: Industrial estates and post-suburban transformation in Jakarta Metropolitan Region. Cities 2012, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybriwsky, R.; Ford, L.R. City profile Jakarta. Cities 2001, 18, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.M.; Solecki, W.D. Consumption, inequity, and environmental justice: The making of new metropolitan landscapes in developing countries. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, A.; Spangenberg, J.H. A guide to community sustainability indicators. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2000, 20, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenthen, M. Environmental Hermeneutics and the Meaning of Nature 2017. pp. 1–15. Available online: https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/155694/3/155694pub.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Horley, C.; Luckman, S.; Gibson, C.; Willoughby-Smith, J. Gis, ethnography, and cultural research: Putting maps back into ethnographic mapping. Inf. Soc. 2010, 26, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Cultural Mapping: Intangible Values and Engaging with Communities with Some Reference to Asia. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2013, 4, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galehbakhtiari, S.; Hasangholi Pouryasouri, T. A hermeneutic phenomenological study of online community participation: Applications of fuzzy cognitive maps. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masassya, E. Collaboration Opportunities to Strengthen Cooperation and Sustainability among Port from Indonesia Port’s Perspective. International Association Ports and Harbour (IAPH) World Ports Conference. 2017. Available online: https://www.iaphworldports.org/n-iaph/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Elvyn_G.Masassya-Bali2017.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Burksiene, V.; Dvorak, J.; Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, G. Sustainability and sustainability marketing in competing for the title of European Capital of Culture. Organizacija 2018, 51, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, H.; Yunus, H.S.; Purwanto, B. The metaphor of “center” in planning: Learning from the geopolitical order of swidden traditions in the land of sunda. J. Reg. City Plan. 2017, 28, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, L. The Culture of Cities; Harvest Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

| Letter | Male/ Female | Age | Years of Residence | Identified Ethnicity | Field of Work/ Organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | M | 37 | 32 | Betawi | Public facilities care/ Karang Taruna youth |

| B | M | 47 | 33 | Betawi- Indramayu | Fisherman/ Kalibaru fishermen co-op |

| C | F | 42 | 42 | Sulawesi | Housewife/ PKK women’s organization |

| D | M | 37 | 22 | Betawi- Indramayu | Public facilities care/ Local mosque assembly |

| E | M | 36 | 36 | Betawi- Indramayu | Fisherman/ Private social foundation |

| F | F | 51 | 26 | Makassar- Sulawesi | Housewife/ PKK women’s organization |

| G | M | 37 | 37 | Bone- Sulawesi | Karang Taruna youth |

| H | F | 49 | 39 | Bugis- Sulawesi | Elementary schoolteacher/ PKK women’s organization |

| I | M | 36 | 36 | Indramayu | Public facilities care/ Local mosque assembly |

| J | M | 28 | 28 | Betawi- Indramayu | Shipping port worker/ Karang Taruna youth |

| Land Use | Area (ha) |

|---|---|

| Residential area | 53.64 |

| Industrial area | 29.56 |

| Government buildings | 0.47 |

| Public facilities | 6.16 |

| Green open space | 4.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Habib, M.H.; Hasibuan, H.S.; Kurniawan, K.R. Cultural Space as Sustainability Indicator for Development Planning (Case Study in Jakarta Coastal Area). Sustainability 2023, 15, 13125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713125

Habib MH, Hasibuan HS, Kurniawan KR. Cultural Space as Sustainability Indicator for Development Planning (Case Study in Jakarta Coastal Area). Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):13125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713125

Chicago/Turabian StyleHabib, Muhammad Hasnan, Hayati Sari Hasibuan, and Kemas Ridwan Kurniawan. 2023. "Cultural Space as Sustainability Indicator for Development Planning (Case Study in Jakarta Coastal Area)" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 13125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713125

APA StyleHabib, M. H., Hasibuan, H. S., & Kurniawan, K. R. (2023). Cultural Space as Sustainability Indicator for Development Planning (Case Study in Jakarta Coastal Area). Sustainability, 15(17), 13125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713125