The Intertwining Effect of Visual Perception of the Reusable Packaging and Type of Logo Simplification on Consumers’ Sustainable Awareness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Pandemic-Induced Changes in Consumption

2.2. Visual Communication

2.3. Environmental Awareness through Packaging

2.4. Logo Simplification

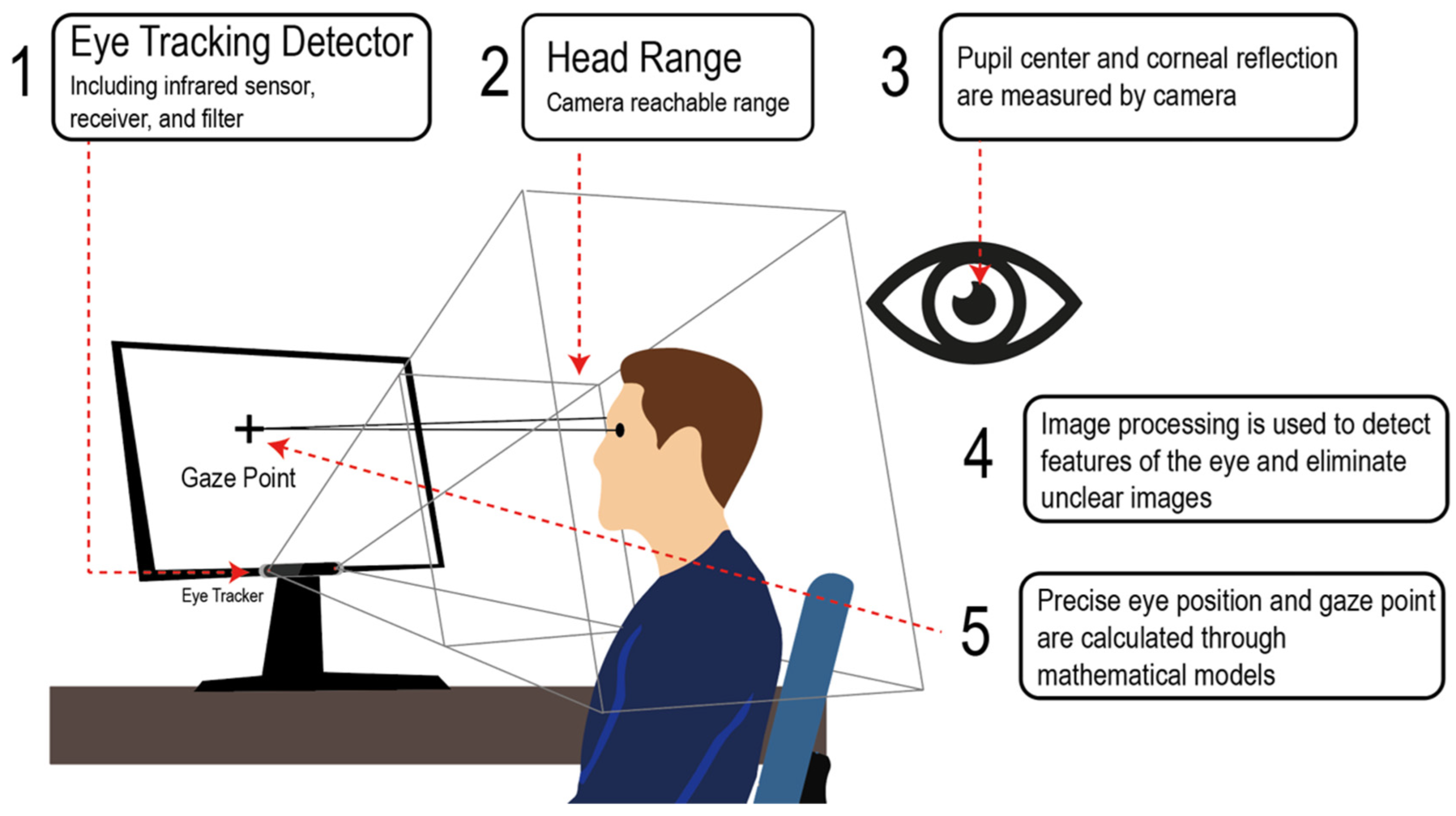

2.5. Visual Perception of the Eye-Tracking System

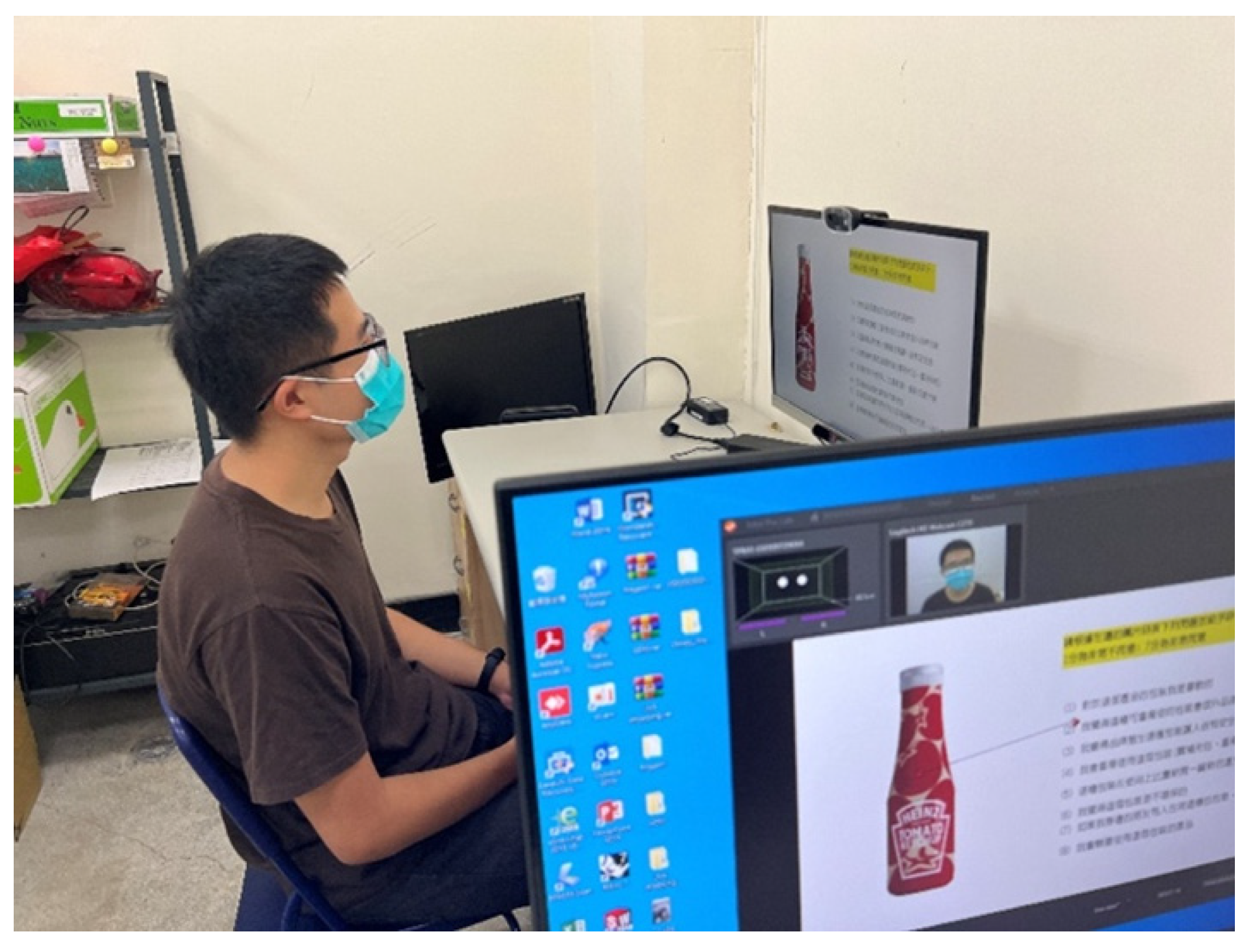

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

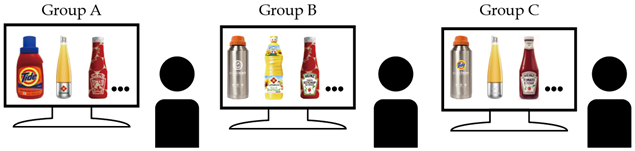

3.2. Material

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Measurement

4. Result

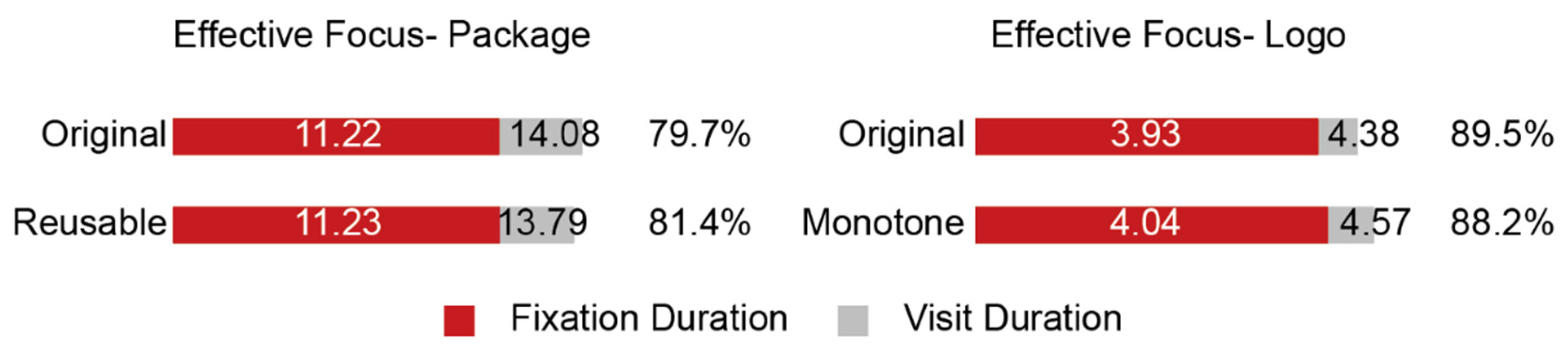

4.1. Physiological Response (Eye-Tracking)

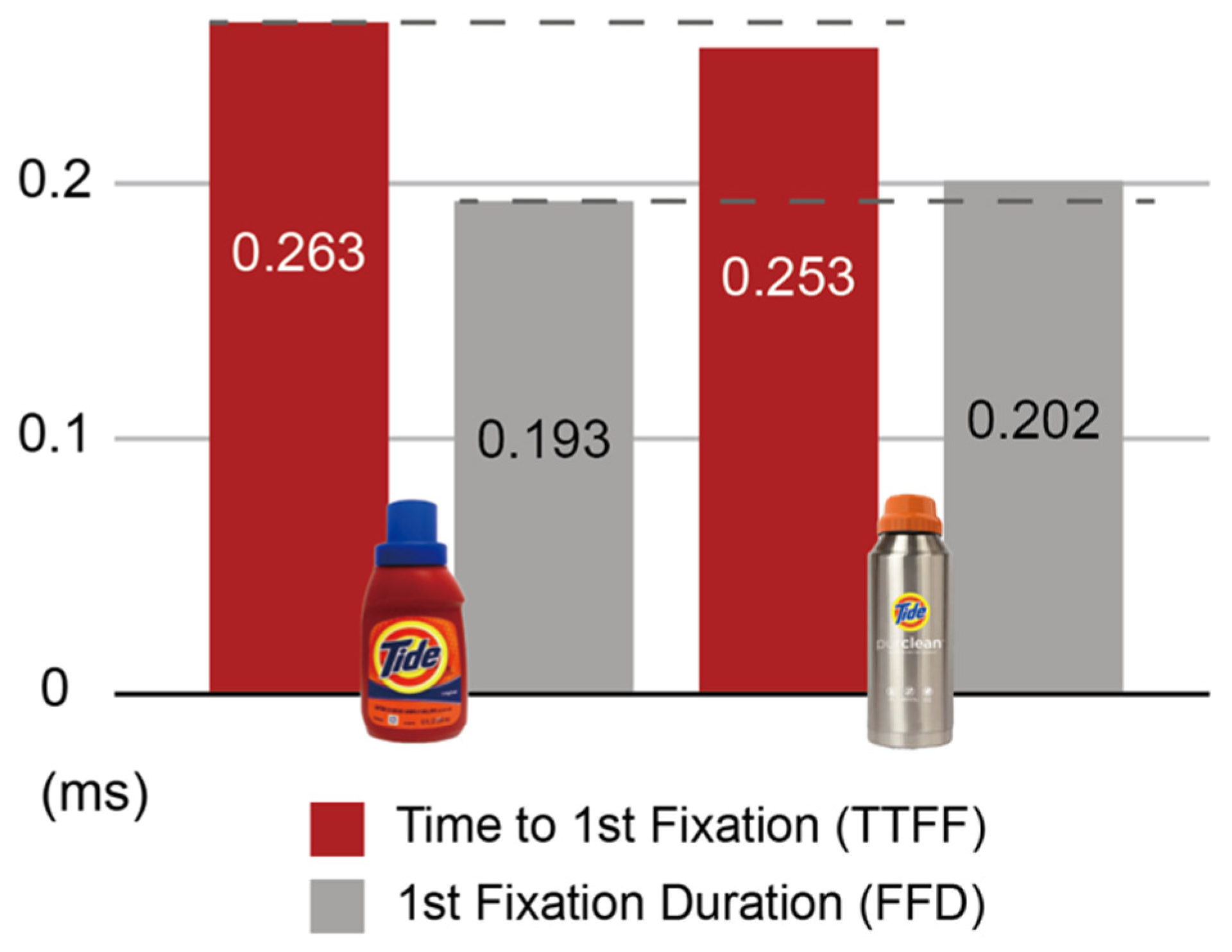

4.1.1. Attraction and Attention on Reusable Package vs. Original Package

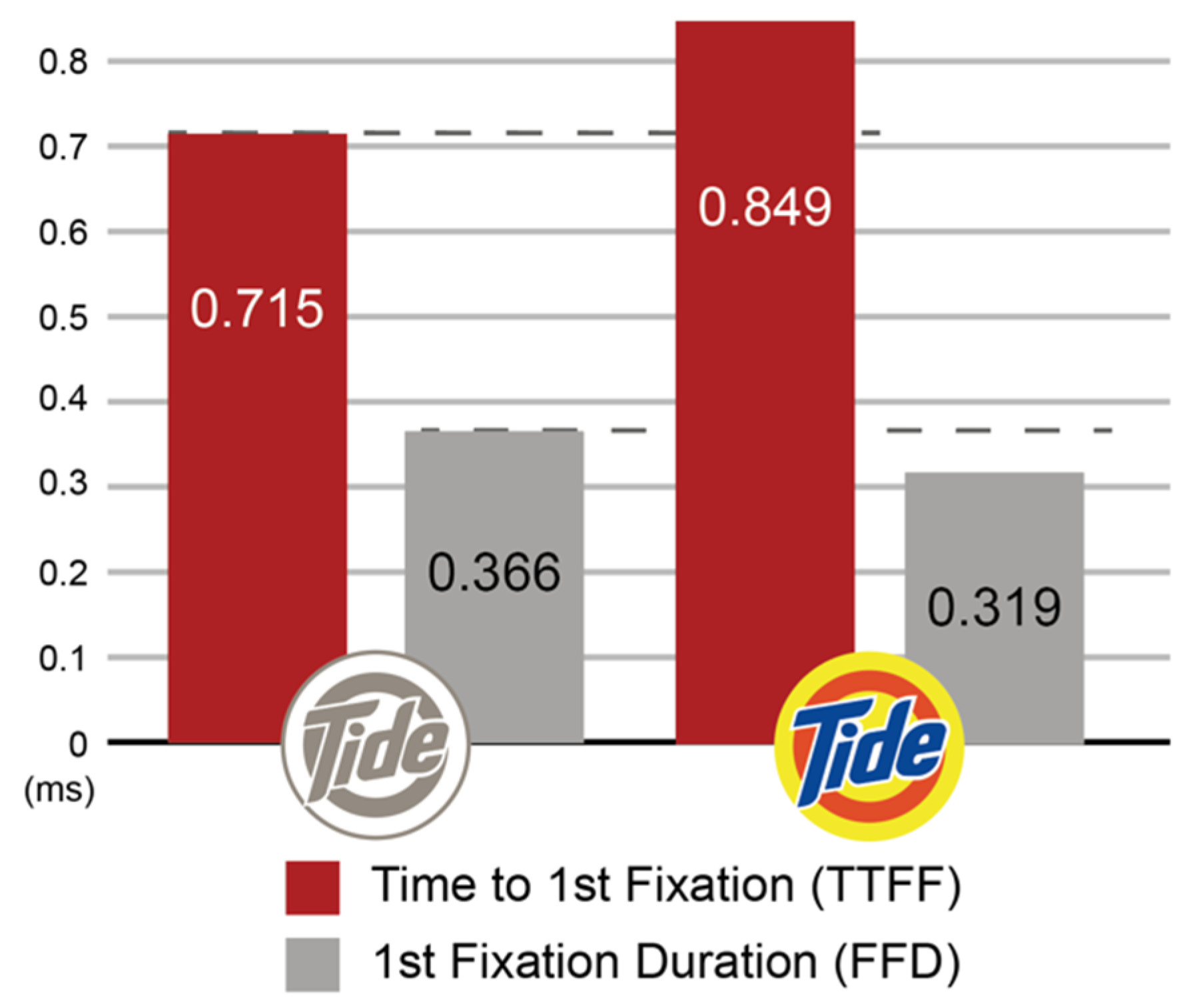

4.1.2. Attraction and Attention on Monotone Logo vs. Original Logo

4.1.3. Proportion of Adequate Attention

4.2. Psychological Response (Questionnaire)

4.2.1. The Package Impact of the Consumption Attitude on Psychological Aspects

4.2.2. The Logo Impact of the Consumption Attitude on the Psychological Aspects

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Physiological Visual Perspective Impact

5.2. Psychological Influence on Consumption

5.3. Conclusions

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garaus, M.; Garaus, C.; Wolfsteiner, E.; Jermendy, C. Anthropomorphism as a Differentiation Strategy for Standardized Reusable Glass Containers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Zhang, H.; Duan, H.; Xu, M. Packaging waste from food delivery in China’s mega cities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 103, 226–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Agostinho, F.; Duan, H.; Song, G.; Wang, X.; Giannetti, B.F.; Santagata, R.; Casazza, M.; Lega, M. Environmental impacts characterization of packaging waste generated by urban food delivery services. A big-data analysis in Jing-Jin-Ji region (China). Waste Manag. 2020, 117, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, W.Q.; de Azeredo, H.M.C.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Food packaging wastes amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Trends and challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Kim, K.N.; Woo, J. Post-consumer plastic packaging waste from online food delivery services in South Korea. Waste Manag. 2023, 156, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husić-Mehmedović, M.; Omeragić, I.; Batagelj, Z.; Kolar, T. Seeing is not necessarily liking: Advancing research on package design with eye-tracking. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favier, M.; Celhay, F.; Pantin-Sohier, G. Is less more or a bore? Package design simplicity and brand perception: An application to Champagne. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 46, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S.; Del Ponte, P. New brand logo design: Customers’ preference for brand name and icon. J. Brand Manag. 2017, 24, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Nadzim, S.Z.A.; Shiratuddin, N. Strategic Use of Social Media for Small Business Based on the AIDA Model. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortinas, M.; Cabeza, R.; Chocarro, R.; Villanueva, A. Attention to online channels across the path to purchase: An eye-tracking study. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 36, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, L.; Bellman, S.; Kennedy, R.; Nenycz-Thiel, M.; Bogomolova, S. Moderating effects of prior brand usage on visual attention to video advertising and recall: An eye-tracking investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 111, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shagass, C.; Roemer, R.A.; Amadeo, M. Eye-Tracking Performance and Engagement of Attention. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1976, 33, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, M.R.; Watson, M.R.; Walshe, R.C.; Maj, F. Extremely selective attention: Eye-tracking studies of the dynamic allocation of attention to stimulus features in categorization. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2009, 35, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, T.; Olatunji, B.O. Eye tracking of attention in the affective disorders: A meta-analytic review and synthesis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 704–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucher, H.-J.; Schumacher, P. The relevance of attention for selecting news content. An eye-tracking study on attention patterns in the reception of print and online media. Communication 2006, 31, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ahn, J.-H. Attention to Banner Ads and Their Effectiveness: An Eye-Tracking Approach. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 17, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisk, S.; Vaswani, A.; Linetzky, M.; Bar-Haim, Y.; Lau, J.Y. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Eye-Tracking of Attention to Threat in Child and Adolescent Anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 88–99.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Antonenko, P.; Dawson, K. Does visual attention to the instructor in online video affect learning and learner perceptions? An eye-tracking analysis. Comput. Educ. 2019, 146, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Priego, N.; Porcu, L.; Peña, M.B.P.; Almendros, E.C. Perceived customer care and privacy protection behavior: The mediating role of trust in self-disclosure. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, J.D.; Redi, A.A.N.P.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Ong, A.K.S.; Young, M.N.; Nadlifatin, R. Choosing a package carrier during COVID-19 pandemic: An integration of pro-environmental planned behavior (PEPB) theory and service quality (SERVQUAL). J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 131123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lai, P.-L.; Yang, C.-C.; Wang, X. Exploring the factors that drive consumers to use contactless delivery services in the context of the continued COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, C.; Fosso-Wamba, S.; Arnaud, J.B. Online consumer resilience during a pandemic: An exploratory study of e-commerce behavior before, during and after a COVID-19 lockdown. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szász, L.; Bálint, C.; Csíki, O.; Nagy, B.Z.; Rácz, B.-G.; Csala, D.; Harris, L.C. The impact of COVID-19 on the evolution of online retail: The pandemic as a window of opportunity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 69, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, N.; Eschenbrenner, B.; Baier, D. Online shopping continuance after COVID-19: A comparison of Canada, Germany and the United States. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 69, 103100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanapalli, K.R.; Sharma, H.B.; Ranjan, V.P.; Samal, B.; Bhattacharya, J.; Dubey, B.K.; Goel, S. Challenges and strategies for effective plastic waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 750, 141514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, E.; Booth, A.M.; Misund, A.; Klun, K.; Rotter, A.; Tiller, R. Single-Use Plastic Bans: Exploring Stakeholder Perspectives on Best Practices for Reducing Plastic Pollution. Environments 2021, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengali, S. The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Unleashing a Tidal Wave of Plastic Waste. The Los Angeles Times. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-06-13/coronavirus-pandemic-plastic-waste-recycling (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Shams, M.; Alam, I.; Mahbub, S. Plastic pollution during COVID-19: Plastic waste directives and its long-term impact on the environment. Environ. Adv. 2021, 5, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T.M.; Baier, D.; Wening, S. Does sustainability really matter to consumers? Assessing the importance of online shop and apparel product attributes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. Sustainability and development after COVID-19. World Dev. 2020, 135, 105082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakovirta, M.; Denuwara, N. How COVID-19 Redefines the Concept of Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S. The influence of visual packaging design on perceived food product quality, value, and brand preference. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J. Visual influence on in-store buying decisions: An eye-track experiment on the visual influence of packaging design. J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silayoi, P.; Speece, M. Packaging and purchase decisions: An Exploratory Study on The Impact of Involvement Level and Time Pressure. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, K.; van der Merwe, D.; de Beer, H.; Kempen, E.; Bosman, M.J.C. Consumers’ perceptions of food packaging: An exploratory investigation in Potchefstroom, South Africa. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 35, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honea, H.; Horsky, S. The power of plain: Intensifying product experience with neutral aesthetic context. Mark. Lett. 2011, 23, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, F. Does ‘chicken soup for the soul’ on the product packaging work? The mediating role of perceived warmth and self-brand connection. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 70, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Madariaga, J.; López, M.-F.B.; Burgos, I.M.; Virto, N.R. Do isolated packaging variables influence consumers’ attention and preferences? Physiol. Behav. 2019, 200, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faultrier, B.; Towers, N. An exploratory packaging study of the composite fashion footwear buying framework. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M. Analysing the complex relationship between logo and brand. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2017, 13, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günay, M. Design in Visual Communication. Art Des. Rev. 2021, 9, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamed, C. Visual Language for Designers: Principles for Creating Graphics That People Understand; Rockport: Beverly, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.D.; Deitz, G.D.; Huhmann, B.A.; Jha, S.; Tatara, J.H. An eye-tracking study of attention to brand-identifying content and recall of taboo advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 111, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopico-Parada, A.; López-Miguens, M.J.; Álvarez-González, P. Building value with packaging: Development and validation of a measurement scale. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, T. New Greenpeace Report: Plastic Recycling Is a Dead-End Street—Year after Year, Plastic Recycling Declines Even as Plastic Waste Increases. GreenPeace. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/news/new-greenpeace-report-plastic-recycling-is-a-dead-end-street-year-after-year-plastic-recycling-declines-even-as-plastic-waste-increases/ (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Guide, V.D.R.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. The Evolution of Closed-Loop Supply Chain Research. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 10–18. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25614727 (accessed on 28 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Guo, Z.; Xue, Y. Dump or recycle? Consumer’s environmental awareness and express package disposal based on an evolutionary game model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 6963–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L.S.; Lane, J.L.; Grant, T.; Pratt, S.; Lant, P.A.; Laycock, B. Environmental impact of biodegradable food packaging when considering food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Jain, T.; Motiani, M. Have Green, Pay More: An Empirical Investigation of Consumer’s Attitude Towards Green Packaging in an Emerging Economy. In Essays on Sustainability and Management; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kaur, R.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E. Prospects of biopolymer technology as an alternative option for non-degradable plastics and sustainable management of plastic wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Tsetse, E.K.K.; Tulasi, E.E.; Muddey, D.K. Green Packaging, Environmental Awareness, Willingness to Pay and Consumers’ Purchase Decisions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Magnier, L.; Mugge, R. Switching to reuse? An exploration of consumers’ perceptions and behaviour towards reusable packaging systems. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 193, 106972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Huang, R.; Jo, M.-S.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. From single-use to multi-use: Study of consumers’ behavior toward consumption of reusable containers. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 193, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation Reuse: Rethinking Packaging. 2019. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/Reuse.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Spence, C.; Van Doorn, G. Visual communication via the design of food and beverage packaging. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2022, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J.; Kristensen, T.; Grønhaug, K. Understanding consumers’ in-store visual perception: The influence of package design features on visual attention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampuero, O.; Vila, N. Consumer perceptions of product packaging. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Gong, X.; Wang, J. Simple = Authentic: The effect of visually simple package design on perceived brand authenticity and brand choice. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 166, 114078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, P.W.; Cote, J.A. Guidelines for Selecting or Modifying Logos. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, J.-N. Strategic Brand Management: New Approaches to Creating and Evaluating Brand Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Melewar, T.C.; Hussey, G.; Srivoravilai, N. Corporate visual identity: The re-branding of France Télécom. J. Brand Manag. 2005, 12, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittard, N.; Ewing, M.; Jevons, C. Aesthetic theory and logo design: Examining consumer response to proportion across cultures. Int. Mark. Rev. 2007, 24, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Kocher, B.; Crettaz, A. The effects of visual rejuvenation through brand logos. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 66, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Liang, M.; Huang, H.; Fan, J.; Yu, L.; Liao, J. The effect of different animated brand logos on consumer response—An event-related potential and self-reported study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adîr, V.; Adîr, G.; Pascu, N.E. How to Design a Logo. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 122, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettels, J.; Wiedmann, K.-P. Brand logo symmetry and product design: The spillover effects on consumer inferences. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 97, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edell, J.A.; Staelin, R. The Information Processing of Pictures in Print Advertisements. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, A.H. Measuring the Value of Corporate and Brand Logos. Des. Manag. J. (Former Ser.) 2010, 4, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Analysis of Visual Communication Packaging Design Based on Interactive Experience. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1852, 022074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, R.; Torres, I.M.; Fazli-Salehi, R.; Zúñiga, M. The effects of campaign-based logo changes on consumers’ attitude and behavior: A case of social distancing messages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cian, L.; Krishna, A.; Elder, R.S. This Logo Moves Me: Dynamic Imagery from Static Images. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 51, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kaur, K. Connecting the dots between brand logo and brand image. Asia-Pacific J. Bus. Adm. 2019, 11, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Jiang, Z. Chinese cultural element in brand logo and purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022, 41, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Cheung, V.; Li, D.; Cassidy, T. Effective Simplification for Logo Design. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED15), Volume 9: User-Centred Design, Design of Socio-Technical Systems, Milan, Italy, 27–30 July 2015; pp. 365–374. [Google Scholar]

- McCloud, S. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art; Harper Perennia: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, U.R.; Crouch, R.C. Is Beauty in the Aisles of the Retailer? Package Processing in Visually Complex Contexts. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northey, G.; Chan, E.Y. Political conservatism and preference for (a)symmetric brand logos. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossel, V.; Geyskens, K.; Goukens, C. Facing a trend of brand logo simplicity: The impact of brand logo design on consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, R.; Winkielman, P.; Schwarz, N. Effects of Perceptual Fluency on Affective Judgments. Psychol. Sci. 1998, 9, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuch, A.N.; Presslaber, E.E.; Stöcklin, M.; Opwis, K.; Bargas-Avila, J.A. The role of visual complexity and prototypicality regarding first impression of websites: Working towards understanding aesthetic judgments. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2012, 70, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvelplund, K.T. Eye tracking and the translation process: Reflections on the analysis and interpretation of eye-tracking data. In MonTI Special Issue—Minding Translation; Special Issue 1; Universitat d’Alacant: Alicante, Spain; Universitat Jaume I: Castelló, Spain; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, P.; Coveyou, M.T.; Behe, B.K. Visual cues during shoppers’ journeys: An exploratory paper. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białowąs, S.; Szyszka, A. Eye-tracking in Marketing Research. In Managing Economic Innovations—Methods and Instruments; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznan, Poland, 2019; pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.T.; Luke, S.G. Best practices in eye tracking research. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2020, 155, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. Eye movements and attention in reading, scene perception, and visual search. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2009, 62, 1457–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, S.; Hyönä, J.; Liversedge, S.P. Developmental eye-tracking research in reading: Introduction to the special issue. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2015, 27, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, M.L.; Federici, S. Gaze and eye-tracking solutions for psychological research. Cogn. Process. 2012, 13, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, R.-M.; Fiedler, S. Understanding cognitive and affective mechanisms in social psychology through eye-tracking. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 85, 103842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahey, J.N.; Oxley, D. The Power of Eye Tracking in Economics Experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemdag, E.; Cagiltay, K. A systematic review of eye tracking research on multimedia learning. Comput. Educ. 2018, 125, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, K.; Pellicer-Sánchez, A. Using eye-tracking in applied linguistics and second language research. Second. Lang. Res. 2016, 32, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyönä, J. The use of eye movements in the study of multimedia learning. Learn. Instr. 2010, 20, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-L.; Tsai, M.-J.; Yang, F.-Y.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Liu, T.-C.; Lee, S.W.-Y.; Lee, M.-H.; Chiou, G.-L.; Liang, J.-C.; Tsai, C.-C. A review of using eye-tracking technology in exploring learning from 2000 to 2012. Educ. Res. Rev. 2013, 10, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannula, D.E.; Althoff, R.R.; Warren, D.E.; Riggs, L.; Cohen, N.J.; Ryan, J.D. Worth a glance: Using eye movements to investigate the cognitive neuroscience of memory. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herten, N.; Otto, T.; Wolf, O.T. The role of eye fixation in memory enhancement under stress—An eye tracking study. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2017, 140, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orquin, J.L.; Loose, S.M. Attention and choice: A review on eye movements in decision making. Acta Psychol. 2013, 144, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, J.R.; Schall, A. Eye Tracking in User Experience Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, J.H.; Wichansky, A.M. Chapter 23—Eye Tracking in Usability Evaluation: A Practitioner’s Guide. In The Mind’s Eye: On Cognitive and Applied Aspects of Eye Movement Research; Hyönä, J., Radach, R., Deubel, H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.J.; Bol, N.; Cummins, R.G.; John, K.K. Improving Visual Behavior Research in Communication Science: An Overview, Review, and Reporting Recommendations for Using Eye-Tracking Methods. Commun. Methods Meas. 2019, 13, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Pieters, R. Eye Tracking for Visual Marketing. Found. Trends Mark. 2006, 1, 231–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, P.; Hutchinson, J.W.; Bradlow, E.; Young, S.H. Measuring the Value of Point-of-Purchase Marketing with Commercial Eye-Tracking Data; INSEAD Business School Research Paper; No. 2007/22/MKT/ACGRD; SSRN—Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khushaba, R.N.; Wise, C.; Kodagoda, S.; Louviere, J.; Kahn, B.E.; Townsend, C. Consumer neuroscience: Assessing the brain response to marketing stimuli using electroencephalogram (EEG) and eye tracking. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 3803–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.V.; Sigurdsson, V.; Larsen, N.M.; Fagerstrøm, A.; Foxall, G.R. Consumer attention to price in social commerce: Eye tracking patterns in retail clothing. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5008–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoste-Badie, S.; Gagnan, A.B.; Droulers, O. Front of pack symmetry influences visual attention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Droulers, O.; Lacoste-Badie, S. Why display motion on packaging? The effect of implied motion on consumer behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Green, C.; Fairley, S. Investigation of the use of eye tracking to examine tourism advertising effectiveness. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, P.T.; Behe, B.K.; Driesener, C.; Minahan, S. Inside-outside: Using eye-tracking to investigate search-choice processes in the retail environment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbring, T.; Wästlund, E.; Gustafsson, A. Eye-tracking customers’ visual attention in the wild: Dynamic gaze behavior moderates the effect of store familiarity on navigational fluency. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, B. 10 Most Used Eye Tracking Metrics and Terms. IMotions. Available online: https://imotions.com/blog/learning/10-terms-metrics-eye-tracking/#a-id-time-a-5-time-spent-dwell-time (accessed on 28 June 2022).

| Original Packaging | Reusable Package + Monotone Logo | Reusable Package + Multi-Color Logo |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

| Schematic diagram of observation groups | ||

| ||

| n. | M | SD | df | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original packages | 72 | 11.222 | 1.895 | 142 | −0.009 | 0.993 |

| Reusable packages | 72 | 11.225 | 2.222 | |||

| note: n. represents the number of product instead of participants. | ||||||

| n. | M | SD | df | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original logo | 72 | 4.036 | 2.391 | 142 | 0.28 | 0.774 |

| Monotone logo | 72 | 3.927 | 2.181 |

| Factor | Object | n. | Mean | SD | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Image | Original Package | 72 | 4.25 | 1.554 | 142 | −3.088 | 0.002 |

| Reusable package | 72 | 4.99 | 1.295 | ||||

| Environmental | Original Package | 72 | 3.76 | 1.827 | 142 | −2.359 | 0.020 |

| Reusable package | 72 | 4.49 | 1.846 | ||||

| Preference | Original Package | 72 | 3.83 | 1.463 | 142 | −3.440 | 0.001 |

| Reusable package | 72 | 4.74 | 1.678 | ||||

| Willing to Use | Original Package | 72 | 3.90 | 1.680 | 142 | −2.686 | 0.008 |

| Reusable package | 72 | 4.65 | 1.671 |

| Factor | Object | n. | Mean | SD | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Image | original logo | 72 | 4.99 | 1.295 | 142 | 1.024 | 0.308 |

| monotone logo | 72 | 5.21 | 1.310 | ||||

| Environmental | original logo | 72 | 4.49 | 1.846 | 142 | 0.148 | 0.882 |

| monotone logo | 72 | 4.53 | 1.510 | ||||

| Preference | original logo | 72 | 4.74 | 1.678 | 142 | 0.876 | 0.774 |

| monotone logo | 72 | 4.96 | 1.347 | ||||

| Willing to Use | original logo | 72 | 4.65 | 1.671 | 142 | 0.752 | 0.453 |

| monotone logo | 72 | 4.85 | 1.421 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiu, T.-P.; Yang, D.J.; Ma, M.-Y. The Intertwining Effect of Visual Perception of the Reusable Packaging and Type of Logo Simplification on Consumers’ Sustainable Awareness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713115

Chiu T-P, Yang DJ, Ma M-Y. The Intertwining Effect of Visual Perception of the Reusable Packaging and Type of Logo Simplification on Consumers’ Sustainable Awareness. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):13115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713115

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiu, Tseng-Ping, Derrick Jessey Yang, and Min-Yuan Ma. 2023. "The Intertwining Effect of Visual Perception of the Reusable Packaging and Type of Logo Simplification on Consumers’ Sustainable Awareness" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 13115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713115

APA StyleChiu, T.-P., Yang, D. J., & Ma, M.-Y. (2023). The Intertwining Effect of Visual Perception of the Reusable Packaging and Type of Logo Simplification on Consumers’ Sustainable Awareness. Sustainability, 15(17), 13115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713115